Abstract

Cofactor F420 plays critical roles in primary and secondary metabolism in a range of bacteria and archaea as a low-potential hydride transfer agent. It mediates a variety of important redox transformations involved in bacterial persistence, antibiotic biosynthesis, pro-drug activation and methanogenesis. However, the biosynthetic pathway for F420 has not been fully elucidated: neither the enzyme that generates the putative intermediate 2-phospho-l-lactate, nor the function of the FMN-binding C-terminal domain of the γ-glutamyl ligase (FbiB) in bacteria are known. Here we present the structure of the guanylyltransferase FbiD and show that, along with its archaeal homolog CofC, it accepts phosphoenolpyruvate, rather than 2-phospho-l-lactate, as the substrate, leading to the formation of the previously uncharacterized intermediate dehydro-F420-0. The C-terminal domain of FbiB then utilizes FMNH2 to reduce dehydro-F420-0, which produces mature F420 species when combined with the γ-glutamyl ligase activity of the N-terminal domain. These new insights have allowed the heterologous production of F420 from a recombinant F420 biosynthetic pathway in Escherichia coli.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cofactor F420 is a deazaflavin that acts as a hydride carrier in diverse redox reactions in both bacteria and archaea1,2. While F420 structurally resembles the flavins flavin mononucleotide (FMN) and flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD), it functions as an obligate two-electron hydride carrier and hence is functionally analogous to the nicotinamides NAD+ and NADP+ 3. The lower reduction potential of the F420, relative to the flavins, results from the substitution of N5 of the isoalloxazine ring in the flavins for a carbon in F4204,5. Originally characterized from methanogenic archaea in 19724,5, F420 is an important catabolic cofactor in methanogens and mediates key one-carbon transformations of methanogenesis6. F420 has since been shown to be synthesized in a range of archaea and bacteria1,2,7,8. In Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the causative agent of tuberculosis, F420 has been shown to contribute to persistence9,10 and to activate the new clinical antitubercular prodrugs delamanid and pretomanid11. There are also growing numbers of natural products that have been shown to be synthesized through F420-dependent pathways, including tetracyclines12, lincosamides13, and thiopeptides14. F420-dependent enzymes have also been explored for bioremediation and biocatalytic applications15,16.

The currently accepted F420 biosynthetic pathway consists of two branches2 (Fig. 1). In the first branch, tyrosine is condensed with 5-amino-6-ribitylamino-2,4[1H,3H]-pyrimidinedione from the flavin biosynthetic pathway to generate the deazaflavin chromophore Fo (7,8-didemethyl-8-hydroxy-5-deazariboflavin) via the activity of the two-domain Fo synthase FbiC, or the CofG/H pair (where “Fbi” refers to mycobacterial proteins and “Cof” refers to archaeal homologs). In the second branch, it has been hypothesized that a 2-phospho-l-lactate guanylyltransferase (CofC in archaea and the putative enzyme FbiD in bacteria) catalyzes the guanylylation of 2-phospho-l-lactate (2-PL) using guanosine-5ʹ-triphosphate (GTP), yielding l-lactyl-2-diphospho-5ʹ-guanosine (LPPG)17. The two branches then merge at the reaction catalyzed by the transferase FbiA/CofD, where the 2-phospho-l-lactyl moiety of LPPG is transferred to Fo, forming F420-018,19. Finally, the γ-glutamyl ligase (FbiB/CofE) catalyzes the poly-glutamylation of F420 to generate mature F420, with poly-γ-glutamate tail lengths of ~2–8, depending on species20,21.

The currently accepted bacterial F420 biosynthesis pathway. The pathway is composed of two branches. In the first branch tyrosine is condensed with the flavin biosynthesis intermediate 5-amino-6-ribitylamino-2,4-(1H,3H)-pyrimidinedione by FbiC/CofGH to produce the riboflavin level chromophore Fo. In the second branch, l-lactic acid is phosphorylated in a guanosine-5ʹ-triphosphate (GTP)-dependent manner by the hypothetical l-lactate kinase CofB to produce 2-phospho-l-lactate (2-PL). This compound is subsequently guanylylated by FbiD/CofC to produce the unstable intermediate l-lactyl-2-diphospho-5ʹ-guanosine (LPPG). The two branches merge as the 2-phospho-l-lactyl moiety of LPPG is transferred to Fo through the action of FbiA/CofD to produce F420-0. Mature F420 is then produced through glutamylation of F420-0 by FbiB/CofE. “Fbi” refers to bacterial proteins, whereas “Cof” represents archaeal ones

There are three aspects of the F420 biosynthetic pathway that require clarification. First, the metabolic origin of 2-PL, the proposed substrate for CofC, is unclear. It has been assumed that a hypothetical kinase (designated CofB) phosphorylates l-lactate to produce 2-PL22. However, no such enzyme has been identified in bacteria or archaea, and our genomic analysis of F420 biosynthesis operons has failed to identify any candidate enzymes with putative l-lactate kinase activity2. Second, the existence of FbiD has only been inferred through bioinformatics and genetic knockout studies and the enzyme has not been formally characterized23,24. Finally, the bacterial γ-glutamyl ligase FbiB is a two-domain protein20, in which the N-terminal domain is homologous to other F420-γ-glutamyl ligases (including the archaeal equivalent, CofE) and the C-terminal domain adopts an FMN-binding nitroreductase (NTR) fold20. Although both domains are required for full γ-glutamyl ligase activity, no function has been associated with either the C-terminal domain or the FMN cofactor, given no redox reactions are known to be involved in F420 biosynthesis.

Here we demonstrate that 2-PL is not required for F420 biosynthesis in prokaryotes and instead phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP), an abundant intermediate of glycolysis and gluconeogenesis, is incorporated into F420. Mass spectrometry (MS) and protein crystallography are used to demonstrate that PEP guanylylation is catalyzed by the FbiD/CofC enzymes that were previously thought to act upon 2-PL. In bacteria, the incorporation of PEP in the pathway results in the production of the previously undetected intermediate dehydro-F420-0, which we identified by MS. We then showed, with the help of ligand docking, that this intermediate is then reduced by the C-terminal domian and poly-glutamylated by the N-terminal domain. These findings result in a substantially revised pathway for F420 biosynthesis and have allowed us to heterologously express a functional F420 biosynthetic pathway in Escherichia coli, an organism that does not normally produce F420, at levels comparable to some native F420-producing organisms.

Results

FbiD/CofC accept PEP, rather than 2-PL

The archaeal enzyme CofC has previously been suggested to catalyze the guanylylation of 2-PL to produce LPPG during F420 biosynthesis (Fig. 2a)25. Another study, using transposon mutagenesis, has shown that MSMEG_2392 of Mycobacterium smegmatis is essential in the biosynthesis of F420 from Fo23. We have recently shown that homologs of this gene have sequence homology to CofC and belong to operons with other validated F420 biosynthetic genes in a wide variety of bacteria2. In keeping with the bacterial naming system, we refer to this enzyme as FbiD. To test the function of this putative bacterial FbiD, we cloned the homologous Rv2983 gene from M. tuberculosis26 into a mycobacterial expression vector and purified heterologously expressed Mycobacterium tuberculosis FbiD (Mtb-FbiD) from M. smegmatis mc24517 host cells. We also expressed and purified Mtb-FbiA (the enzyme thought to transfer the 2-phospho-l-lactyl moiety of LPPG to Fo to produce F420-0)18 to use in coupled high-performance liquid chromatography-MS (HPLC-MS) enzymatic assays with Mtb-FbiD. Surprisingly, we found that when Mtb-FbiD and Mtb-FbiA were included in an assay with 2-PL, GTP (or ATP), and Fo, no product was formed (Fig. 2b). We then tested whether Mtb-FbiA and CofC from Methanocaldococcus jannaschii (Mj-CofC) could catalyze F420-0 formation under the same conditions, which again yielded no product (Fig. 2b).

Phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) is an intermediate in the formation of dehydro-F420-0. a Production of F420-0 in our revised biosynthesis pathway (left) compared to the currently accepted pathway (right). b Coupled-reaction high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) assays showing that both Mtb-FbiD and CofC from Methanocaldococcus jannaschii (Mj-CofC) enzymes use PEP to produce dehydro-F420-0. c Tandem mass spectral identification of dehydro-F420-0. Tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) fragmentation of dehydro-F420-0, showing fragment ions with their corresponding structures. The inset displays the observed spectrum of the parent molecule (expected monoisotopic m/z 512.0711 [M − H]−)

Although 2-PL is hypothesized to be an intermediate in F420 biosynthesis, this has never been experimentally confirmed in bacteria. Additionally, no enzyme capable of phosphorylating l-lactate to 2-PL has been identified in F420-producing organisms, despite considerable investigation22. 2-PL has been little studied as a metabolite and is only known to occur as a by-product of pyruvate kinase activity27. 2-PL has not been implicated as a substrate in any metabolic pathway outside the proposed role in F420 biosynthesis; rather, it has been shown in vitro to inhibit several enzymes involved in glycolysis and amino acid biosynthesis28,29,30. Our inability to detect activity with 2-PL led us to consider alternative metabolites that could potentially substitute for 2-PL, including the structurally analogous and comparatively abundant molecule PEP31 (Fig. 2a).

While there was no activity when 2-PL was used in the FbiD/CofC:FbiA-coupled assays, when these enzymes were incubated with PEP, GTP (or ATP), and Fo, a previously unreported intermediate in the F420 biosynthesis pathway, which we term “dehydro-F420-0,” was produced (Fig. 2b). The identity of this compound, which is identical to F420-0 except for a methylene group in place of the terminal methyl group, was verified by MS/MS (Fig. 2c). The only difference that we observed between the activities of Mtb-FbiD and Mj-CofC was that while Mtb-FbiD exclusively utilizes GTP to produce dehydro-F420-0, Mj-CofC can also catalyze the reaction with ATP, albeit to a lesser extent (Fig. 2b). Interestingly, in our experiments the FbiD/CofC enzymes were only active in the presence of FbiA. This was not unexpected given that the inferred intermediate (enolpyruvyl-diphospho-5ʹ-guanosine (EPPG)) is expected to be unstable22 (Fig. 2a).

To understand the molecular basis of PEP recognition by Mtb-FbiD, we crystallized the protein and solved the structure by selenium single-wavelength anomalous diffraction (Se-SAD), and then used this selenomethionine-substituted structure to obtain the native FbiD structure by molecular replacement. The latter was then refined at 1.99 Å resolution (R/Rfree = 0.19/0.22) (Table 1). As expected, Mtb-FbiD adopts the same MobA-like nucleoside triphosphate transferase family protein fold as CofC: a central 7-stranded β-sheet (six parallel strands and one antiparallel), with α-helices packed on either side (Fig. 3a). However, Mtb-FbiD lacks the protruding hairpin that is important for dimer formation in CofC32. Superposition of CofC from Methanosarcina mazei (PDB code 2I5E) onto Mtb-FbiD gives a root mean square difference of 1.85 Å over 181 Cα atoms, with 25.4% sequence identity, establishing clear structural homology (Fig. 3c).

Crystal structure of Mtb-FbiD. a Electrostatic surface representation of the Mtb-FbiD structure in complex with phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP), shown as a ball-and-stick model. b The phosphate group of PEP binds to three aspartic acid side chains through two Mg2+ ions (shown in cyan). PEP is shown in 2Fo − Fc omit density contoured at 2.0σ, and drawn as ball-and-stick model. Water molecules are shown as red spheres and hydrogen bond interactions are outlined as dashed lines. c Superposition of Mtb-FbiD (wheat ribbon) and Methanocaldococcus jannaschii (Mj-CofC) (green ribbon), indicating 1.85 Å root mean square difference (rmsd) over 181 superimposed Cα. PEP is shown as a ball-and-stick model

We also soaked PEP into pre-formed FbiD crystals to obtain an FbiD-PEP complex (2.18 Å resolution, R/Rfree = 0.22/0.26). FbiD has a cone-shaped binding cleft with a groove running across the base of the cone, formed by the C-terminal end of the central β-sheet (Fig. 3a). PEP binds in the cleft with its phosphate group anchored through two Mg2+ ions to three acidic side chains (D116, D188, and D190) (Fig. 3b). This three-aspartate motif is conserved amongst FbiD homologs as shown by a multiple sequence alignment (Supplementary Fig. 1). The PEP carboxylate group is hydrogen bonded to the hydroxyl group of S166 and the main chain NH groups of T148 and G163. All PEP binding residues are conserved in the CofC protein of M. mazei (PDB code 2I5E) (Supplementary Fig. 1), consistent with the enzymatic assays that showed PEP is the substrate for archaeal CofC, as well as FbiD. The reason that FbiD/CofC is active with PEP rather than 2-PL is most likely a consequence of the different stereochemistry of 2-PL (compared with the planar geometry of PEP) preventing a necessary structural rearrangement, or the binding of GTP, which would be required to attain a productive transition state, as suggested for PEP carboxykinase33. In the GTP-bound structure of E. coli MobA34 (PDB code 1FRW), GTP binds in a characteristic surface groove, providing a structural framework for substrate binding and catalysis. In our enzyme assays, neither FbiD nor CofC showed activity in the absence of FbiA. Moreover, we did not observe GTP binding in either our co-crystallization or differential scanning fluorimetry experiments. We speculate that the GTP binding site is not formed until FbiD/CofC interacts with FbiA/CofD, enabling catalysis to proceed through to formation of dehydro-F420-0. This may provide an advantage by producing EPPG/EPPA only when both proteins are available, thereby overcoming the issue of intermediate instability.

The C-terminal domain of FbiB reduces dehydro-F420-0 to F420-0

Dehydro-F420-0 would yield F420-0 upon reduction of the terminal methylene double bond. However, no masses corresponding to F420-0 were identified in any of the liquid chromatography-MS (LC-MS) traces from the FbiD:FbiA-coupled assays, suggesting that an enzyme other than FbiD or FbiA catalyzes dehydro-F420-0 reduction. We have previously shown that full-length FbiB consists of two domains: an N-terminal domain that is homologous to the archaeal γ-glutamyl ligase CofE21,35, and a C-terminal domain of the NTR fold36 that binds to FMN and has no known function, but is essential for extending the poly-γ-glutamate tail20.

We tested whether FbiB could use dehydro-F420-0 as a substrate with a three enzyme assay in which FbiB and l-glutamate were added to the FbiD:FbiA-coupled assay. Mtb-FbiB was observed to catalyze the addition of l-glutamate residues to dehydro-F420-0, forming dehydro-F420 species with one ([M + H]+, m/z of 643.40) and two ([M + H]+, m/z of 772.40) glutamate residues (Supplementary Fig. 2). We then tested the hypothesis that the orphan function of the FMN-binding C-terminal domain could in fact be a dehydro-F420-0 reductase. We used a four-enzyme in vitro assay where E. coli NAD(P)H:flavin oxidoreductase37 (Fre), FMN, NADH, and 10 mM dithiothreitol (to maintain reducing conditions and generate reduced FMNH2) were added to the FbiD:FbiA:FbiB assay and the reaction was performed in anaerobic conditions (to prevent reaction of FMNH2 with oxygen). We found that F420-1, that is, the fully reduced and mature glutamylated cofactor, was produced, but only in the presence of both FbiB and Fre/FMNH2 (Fig. 4a). Thus, dehydro-F420-0 is a bona fide metabolic intermediate that can be converted to mature F420 by FbiB in an FMNH2-dependent fashion. These results demonstrate that bacterial FbiB is a bifunctional enzyme, functioning as a dehydro-F420-0 reductase and as a γ-glutamyl ligase (Fig. 4b).

Mtb-FbiB catalyzes reduction of dehydro-F420-0. a F420-1 is produced in FbiD:FbiA:FbiB coupled assays in the presence of Fre/FMNH2 and l-glutamate. Tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) confirmation of F420-1 in both negative (643.12811, [M − H]−) and positive (645.27094, [M + H]+) modes. b Mtb-FbiB is a bifunctional enzyme catalyzing the reduction of dehydro-F420-0 and its poly-glutamylation to form F420-n. c Docking of FMNH2 and dehydro-F420-0 into the crystal structure of FbiB C-terminal domain. The methylene group of the enolpyruvyl moiety sits in a pocket made up of M372 and P289, while the carboxylate hydrogen bonds with R337. The methylene double bond sits planar above the isoalloxazine ring of FMNH2 at an appropriate distance (3.6 Å, shown by dashed line) and oriented for a hydride transfer to the Si face of the methylene bond, accounting for the observed (S)-lactyl moiety of F420

When the previously published crystal structures of Mtb-FbiB are analyzed in the context of these results, the molecular basis for this activity becomes clear. Crystal structures of the Mtb-FbiB C-terminal domain with F420 bound (PDB ID: 4XOQ) and FMN bound (PBD ID: 4XOO) have been solved20, and when these are overlaid it is apparent that the FMN molecule is ideally situated to transfer a hydride to the terminal methylene of dehydro-F420-0 (assuming dehydro-F420-0 binds in a similar fashion to F420). Interestingly, the phospholactyl group of F420 appears to be disordered in these crystal structures, suggesting it may adopt multiple conformations. To test this, we docked dehydro-F420-0 into the FMNH2-bound structure and performed an energy minimization using the OPLS3e forcefield to allow them to attain a low-energy conformation. This forcefield was chosen based on its improved torsional parameters for small molecules and more accurate descriptions of the potential energy surfaces of ligands, allowing for improved docking poses over other forcefields38. The results show that in this ternary complex the two molecules can adopt ideal positions and orientations for the reduction of dehydro-F420-0 (Fig. 4c). The methylene group of dehydro-F420-0 is accommodated by a small hydrophobic pocket mostly comprised of P289 and M372 allowing it to be positioned above the N5 atom of FMNH2, in a plausible Michaelis complex for hydride transfer (Fig. 4c). We therefore suggest that the phosphoenolpyruvyl (analogous to the phospholactyl) group of dehydro-F420-0 most likely samples conformations within this pocket where it can be reduced.

Interestingly, the γ-glutamyl ligase CofE from archaea is a single domain enzyme; there is no homology to the C-terminal NTR-fold domain of FbiB. In an analogous situation, Fo synthesis is performed by two single domain enzymes in archaea, CofH, and CofG2, whereas in bacteria this reaction is catalyzed by a two-domain protein, FbiC (with N- and C-terminal domains homologous to CofH and CofG, respectively). Previous analysis of archaeal genomes revealed that cofH and cofG are closely associated in genomic context39. We therefore investigated the genomic context of archaeal cofE genes to investigate whether genes with homology to the C-terminal NTR domain of FbiB were located nearby. From over 1000 archaeal genomes, we only detected 16 open reading frames (ORFs) in the neighboring context of cofE that could encode proteins with an NTR fold, although none of these shared substantial (>34% sequence identity) homology and all lacked the key F420 binding residues observed in FbiB. There was one interesting exception: the unusual archaea Lokiarchaeum sp.40 are unique among all sequenced archaea in that they alone encode an FbiB-like γ-glutamyl ligase:NTR fusion protein.

Expression of fbiABCD is sufficient to produce F420 in Escherichia coli

Cofactor F420 is only produced by certain bacterial species; the majority of bacteria, including E. coli, lack the genes required for F420 biosynthesis. Our in vitro assay results suggest that 2-PL and, by extension, the hypothesized l-lactate kinase CofB are not required for heterologous production of F420 in a non-native organism. To test our hypothesis, we generated a plasmid expressing the M. smegmatis F420 biosynthesis genes fbiB/C/D along with the fbiA homolog cofD from M. mazei19, which was substituted as Ms-FbiA was found to express poorly in E. coli.

We generated two versions of a plasmid-encoded recombinant F420 biosynthetic operon, both of which encode codon-optimized genes for expression in E. coli: one encodes the native enzymes (pF420), and the second encodes C-terminal FLAG-tagged versions of the enzymes to allow their detection in a western blot (pF420-FLAG) (Fig. 5a). Plasmids were designed to allow induction of F420 biosynthesis in the presence of anhydrotetracycline. A Western blot using anti-FLAG antibodies was used to detect whether the proteins were expressed in soluble form in E. coli, and confirmed that all were expressed to varying degrees (Supplementary Fig. 3). We then tested, using HPLC with fluorescence detection, whether F420 was heterologously produced in the cell lysate of our recombinant E. coli strain expressing this operon. As shown in Fig. 5b, E. coli expressing both the FLAG-tagged and untagged plasmids produced traces consistent with mature, poly-glutamylated F420, although they differed slightly to the M. smegmatis-produced F420 standard in terms of the distribution of poly-γ-glutamate tail lengths. We also observed some accumulation of Fo (Supplementary Fig. 4), an intermediate formed by FbiC, which is also observed when F420 is produced in M. smegmatis41.

Heterologous expression of F420 biosynthesis pathway in E. coli. a Schematic representation of the vector generated for expression of the F420 biosynthesis pathway. b High-performance liquid chromatography-fluorescence detector (HPLC-FLD) traces of E. coli lysates containing F420 biosynthesis constructs as well as a purified standard from M. smegmatis. c Kinetic studies indicate an identical Michaelis constant for glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (FGD) as measured with F420 purified from M. smegmatis (blue squares) and E. coli (red circles). Error bars represent standard deviations. d Fragmentation of F420-4 and F420-5 extracted from E. coli shows a mature F420 production

To confirm that this was indeed mature F420, and not dehydro-F420 species, we purified the compound from E. coli lysate and performed high-resolution tandem MS (MS/MS) analysis. Mass fragmentation did indeed show that the compound was reduced, and not dehydro-F420 (Fig. 5d). No dehydro-F420 species were detected. The yield of purified F420 was ~27 nmol L−1 of culture, which is comparable to physiological levels of several F420-producing species42. Ultraviolet–visible (UV–Vis) and fluorescence spectra of the purified F420 matched literature values (Supplementary Fig. 5)4,5. Finally, we confirmed that the purified cofactor was functional by measuring enzyme kinetic parameters with F420-dependent glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (FGD) from M. smegmatis (Fig. 5c). The apparent Michaelis constant was within error of that observed with FGD and F420 produced from M. smegmatis, while the kcat was approximately half that of the M. smegmatis F420 (Fig. 5c), which could result from slight differences in the distribution of tail lengths, as previously reported (Supplementary Table 2)43. These results confirm that the heterologous production of F420 was achieved with a biosynthetic pathway containing only CofD (a homolog of FbiA)/FbiB/FbiC/FbiD.

Having demonstrated that our recombinant E. coli strain could produce mature F420 that was functional ex vivo, we tested whether co-expression of F420-dependent enzymes could facilitate F420-dependent transformations in vivo. We have previously shown that F420H2 can decolorize malachite green nonenzymatically, and that several F420-dependent reductases accelerate this reaction44. As summarized in Supplementary Table 3, E. coli were unable to decolorize malachite green without induction of F420 biosynthesis. When the cells additionally expressed FGD and the F420-dependent oxidoreductase MSMEG_2027, malachite green decolorization was significantly increased (p < 0.001, Student’s paired t test, two-sided). These results demonstrate that incorporation of the F420 biosynthetic pathway into E. coli allows F420-dependent enzymes to function in vivo upon heterologous expression.

Discussion

It has become widely accepted within the field that one of the essential initial steps in F420 biosynthesis involves a hypothetical l-lactate kinase that produces 2-PL, which is subsequently incorporated into F420 through the activities of CofC and CofD. However, neither bioinformatics nor genetic knockout studies have identified plausible candidate genes for a l-lactate kinase2,18,23. Furthermore, 2-PL has been shown to inhibit several enzymes involved in central metabolism28,29,30. In terms of pathway flux, this makes 2-PL an unusual starting point for biosynthesis of an abundant metabolite such as F420, which can exceed 1 μM in some species42. The results presented in this paper unequivocally demonstrate that PEP, rather than 2-PL, is the authentic starting metabolite in bacteria. These results reconcile the previously problematic assumptions that are required to include 2-PL within the biosynthetic pathway and establish a revised pathway (Fig. 6) that is directly linked to central carbon metabolism (via PEP) through the glycolysis and gluconeogenesis pathways.

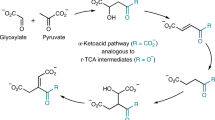

The revised bacterial F420 biosynthesis pathway. The revised pathway is a modified scheme showing that phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) acts as the substrate for the FbiD/CofC enzymes to produce enolpyruvyl-diphospho-5ʹ-guanosine (EPPG) or enolpyruvyl-diphospho-5ʹ-adenosine (EPPA) (in the case of CofC). The immediate reaction product formed from Fo and EPPG/EPPA is dehydro-F420-0, which is reduced to F420-0 through the newly described reductase activity of the C-terminal domain of FbiB in mycobacteria. A separate enzyme in archaea and some bacteria is expected to catalyze this reduction step (CofX). FbiB/CofE subsequently adds a poly-γ-glutamate tail to form F420. “Fbi” refers to bacterial proteins, whereas “Cof” represents archaeal ones

Our observation that CofC accepts PEP (and not 2-PL) in vitro, appear to contradict previous studies in which Mj-CofC was reported to use 2-PL as substrate19,35. However, this discrepancy is most likely due to the supplementation of the coupled CofC/CofD reaction in these studies with pyruvate kinase and 2 mM PEP, a strategy that was used to overcome apparent product inhibition by GMP19,35. Regardless, we cannot explain how a pathway starting from PEP can produce mature (i.e., not dehydro-F420) F420 in archaea given that their equivalent of FbiB (CofE) lacks the C-terminal domain dehydro-F420-0 reductase domain seen in FbiB. One possibility is that an unknown dehydro-F420-0 reductase exists elsewhere in the genome (remote from CofE). Further studies are required to resolve this step in archaeal F420 biosynthesis.

The discovery of dehydro-F420-0 as the product of FbiD:FbiA activity in mycobacteria indicated that another enzyme must be required to reduce dehydro-F420-0 and produce F420-0. This allowed us to define the function of the orphan C-terminal domain of mycobacterial FbiB20. The N-terminal domain is homologous with the archaeal γ-glutamyl ligase CofE35, but is only capable of catalyzing glutamylation of F420-120. The C-terminal domain, which binds both F420 and FMN, is essential for extending the poly-γ-glutamate tail of F420-020, but we could not explain the possible function of the FMN cofactor. Here, we show that FbiB can catalyze both poly-glutamylation and reduction of dehydro-F420-0, via the activities of the N- and C-terminal domains, respectively.

The increasing recognition of the importance of F420 in a variety of biotechnological, medical, and ecological contexts underlines the need for making the compound more widely accessible to researchers; however, our inability to produce F420 recombinantly in common laboratory organisms has been a major barrier to wider study. Here, we confirm the results of our in vitro experiments by showing that recombinant expression of the four characterized F420 biosynthesis genes allows production of F420 in E. coli. These findings should now facilitate the use of F420 in a variety of processes with recombinant organisms, such as biocatalysis using a bio-orthogonal cofactor, directed evolution of F420-dependent enzymes, recombinant production of antibiotics for which F420 is a required cofactor, and metabolic engineering.

Methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

Protein expression utilized either M. smegmatis mc2451745, E. coli BL21(DE3), or LOBSTR-BL21(DE3)46 cells. For growth of M. smegmatis, media were supplemented with 0.05% (v/v) Tween-80. Mycobacterium smegmatis cells were grown in ZYM-505247 or modified auto-induction media Terrific Broth (TB) 2.0 (2.0% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 0.5% NaCl, 22 mM KH2PO4, 42 mM Na2HPO4, 0.6% glycerol, 0.05% glucose, 0.2% lactose)48. For selenomethionine labeling, cells were grown in PASM-5052 media47. Escherichia coli expressions were conducted in either the above-modified auto-induction media or TB medium modified for auto-induction of protein expression (1.2% tryptone, 2.4% yeast extract, 72 mM K2HPO4, 17 mM KH2PO4, 2 mM MgSO4, 0.8% glycerol, 0.015% glucose, 0.5% lactose, 0.375% aspartic acid), grown for 4 h at 37 °C followed by overnight incubation at 18 °C.

Protein expression and purification

Mtb-FbiD: The ORF encoding FbiD (Rv2983) was obtained by PCR from M. tuberculosis H37Rv genomic DNA (Supplementary Table 1). The pYUBDuet-fbiABD co-expression construct was then prepared by cloning fbiD into pYUBDuet41 using BamHI and HindIII restriction sites, followed by cloning the fbiAB operon using NdeI and PacI restriction sites. This construct expresses FbiD with an N-terminal His6-tag, whereas the FbiA and FbiB proteins are expressed without any tags.

The pYUBDuet-fbiABD vector was transformed into M. smegmatis mc24517 strain45 for expression. The cells were grown in a fermenter (BioFlo®415, New Brunswick Scientific) for 4 days before harvesting. The cells were lysed in 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, and 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol using a cell disruptor (Microfluidizer M-110P) in the presence of Complete protease inhibitor mixture mini EDTA-free tablets (Roche Applied Science). The lysate was centrifuged at 20,000 × g to separate the insoluble material. Recombinant FbiD was separated from other proteins by immobilized metal affinity chromatography on a HisTrap FF 5-mL Ni-NTA column (GE Healthcare), eluted with imidazole, and further purified by size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) on a Superdex 75 10/300 column (GE Healthcare) pre-equilibrated in 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, and 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol.

Mtb-FbiA: The ORF encoding M. tuberculosis FbiA was commercially synthesized and cloned into pRSET-A (Invitrogen). The pYUB28b-fbiA construct used for expression in M. smegmatis mc24517 was prepared by subcloning fbiA into pYUB28b41 using an NdeI site introduced by overhang PCR utilizing the HindIII restriction site present on both vectors amplified with the T7 reverse primer (Supplementary Table 1). The resulting pYUB28b-fbiA construct expresses FbiA with an N-terminal His6-tag. The protein was expressed in M. smegmatis mc24517 in ZYM-5052 media auto-induction media47,49 in a fermenter (BioFlo®415, New Brunswick Scientific) for 4 days. The protein was then purified using Ni-NTA and SEC steps, as described above, in 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, and 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol.

Mj-CofC: The ORF encoding Methanocaldococcus jannaschii CofC (MJ0887)25 was synthesized (GenScript) and cloned into pYUB28b vector41 using NdeI and HindIII restriction sites. The protein was expressed in E. coli in TB auto-induction media and purified using Ni-NTA and SEC steps, as described above, in 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, and 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol.

Ec-Fre: The E. coli flavin reductase37 was cloned into pProEX-HTb using KasI and HindIII restriction sites (Supplementary Table 1). Protein expression and purification was performed similar to Mj-CofC.

Ms-FbiD: The ORF encoding M. smegmatis FbiD (MSMEG_2392) was synthesized (Integrated DNA Technologies) and cloned into pETMCSIII by Gibson Assembly as outlined previously48. The protein was expressed overnight ay 30 °C in auto-induction media and purified similarly to Mj-CofC.

Construction of synthetic F420 biosynthesis operon

Ribosome binding sites were individually optimized for each of the codon-optimized F420 biosynthesis genes using the Ribosome Binding Site Calculator server39,50. Multiple operon designs were analyzed using the server’s operon calculator and modified to remove unwanted translation products and RNA instability elements while maintaining predicted translation initiation rates for all coding sequences within an order of magnitude. The final design placed the operon under the control of the tetracycline-inducible promoter BBa_R0040 and the artificial terminator BBa_B1006. For subsequent assembly the operon was flanked by BioBrick prefix and suffix sequences. The operon was synthesized by GenScript and cloned into pSB1C3 containing the constitutive tetracycline repressor cassette BBa_K145201 using the standard BioBrick assembly protocol with EcoRI and XbaI/SpeI restriction enzymes51. This construct, hereafter referred to as pF420, enables production of F420 to be induced by the addition of anhydrotetracycline. For Western blot analysis as second version of the operon with single C-terminal FLAG tags on all four genes was likewise synthesized.

To test for in vivo F420-depended reductase/oxidase activity, the ORF of M. smegmatis FGD (MSMEG_0777) was codon optimized and commercially synthesized by GenScript and cloned into multiple cloning site 1 of pCOLADuet-1 (Novagen) using NcoI and HindIII sites. Subsequently MSMEG_2027 was subcloned from pETMCSIII-MSMEG_202748 into multiple cloning site 2 using NdeI and KpnI to give pFGD_2027.

Mtb-FbiD crystallization and structure determination

Apo-FbiD (20 mg mL−1 in 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol) was crystallized using the sitting drop vapor diffusion method in 30% polyethylene glycol 1500, 3% MPD (2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol), 0.2 M MgSO4, and 0.1 M sodium acetate, pH 5.0. For experimental phasing, selenomethionine-substituted FbiD crystals were grown using protein produced in M. smegmatis host cells49. Se-SAD anomalous diffraction data sets were collected at the Australian Synchrotron. Data collection statistics are summarized in Table 1. Crystals of Mtb-FbiD in complex with PEP were obtained by soaking pre-formed apo crystals in precipitant solutions containing 10 mM PEP for 30 min.

All data sets were indexed and processed using XDS52, and scaled with AIMLESS53 from the CCP4 program suite54. The structure was solved using the SAD protocol of Auto-Rickshaw55, the EMBL-Hamburg automated crystal structure determination platform. Based on an initial analysis of the data, the maximum resolution for substructure determination and initial phase calculation was set to 2.83 Å. All three of the expected heavy atoms were found using the program SHELXD56. The initial phases were improved using density modification and phase extension to 2.33 Å resolution using the program RESOLVE57. Cycles of automatic model building by ARP/wARP58 and phenix.autobuild59 resulted in a protein model that was completed manually using COOT60. Water molecules were identified by their spherical electron density and appropriate hydrogen bond geometry with the surrounding structure. Following each round of manual model building, the model was refined using REFMAC561, against the data to 1.99 Å resolution. The PDB_redo program62 was used in the final stages of refinement. Full refinement statistics are shown in Table 1.

The structure of Mtb-FbiD in complex with PEP was solved by molecular replacement using PHASER63 with the apo-FbiD structure as a search model. The structure was refined by cycles of manual building using COOT60 and refinement using REFMAC561, against the data to 2.18 Å resolution. Full refinement statistics are shown in Table 1. The Ramachandran statistics analyzed using MolProbity64 are 99.18% favored, 0.82% allowed, and 0.0% outliers for apo-FbiD and 99.02% favored, 0.98% allowed, and 0.0% outliers for PEP-FbiD.

Multiple sequence alignments were performed using Expresso from the T-Coffee suite65 with the structure of Mtb-FbiD. Figures were prepared using the ESPript 3.0 web server66.

HPLC assays

FbiD/CofC-FbiA-coupled activity was monitored in a reaction mixture containing 100 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 2 mM GTP, 0.1 mM Fo, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM 2-PL or PEP, 1 μM FbiD, and 5 μM FbiA. The reactions were incubated at 37 °C and stopped using 20 mM EDTA at various time points. Separation of F420 species was performed on an Agilent HP 1100 HPLC system equipped with photodiode array and fluorescence detectors (Agilent Technologies). Samples were kept at 4 °C, and the injection volume was 20 μL. Samples were separated on a Phenomenex Luna C18 column (150 × 3 mm2, 5 μm) with a 0.2 μm in-line filter that was maintained at 30 °C. The mobile phase consisted of 100% methanol (A) and 25 mM sodium acetate buffer, pH 6.0 (B), with a gradient elution at a flow rate of 0.5 mL min−1 and a run time of 30 min. The gradient profile was performed as follows: 0–25 min 95–80% B, 25–26 min 80% B, 26–27 min 95% B, 27–30 min 95% B, and a post-run of 2 min. The wavelengths used for photodiode array were 280 and 420 nm (bandwidth 20 nm) using a reference of 550 nm (bandwidth 50 nm). The wavelengths used for the fluorescence detector were 420 nm (excitation) and 480 nm (emission).

LC-MS characterization of dehydro-F420 species

Enzymatic reactions were set up as described above. Ten microliters aliquots were injected onto a C18 trap cartridge (LC Packings, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) for desalting prior to chromatographic separation on a 0.3 × 100 mm2 3.5 μm Zorbax 300SB C18 Stablebond column (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) using the following gradient at 6 μL min−1: 0–3 min 10% B, 24 min 50% B, 26 min 97% B, 29 min 97% B, 30.5 min 10% B, 35 min 10% B, where A was 0.1% formic acid in water and B was 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile. The column eluate was ionized in the electrospray source of a QSTAR-XL Quadrupole Time-of-Flight mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). For IDA (Information Dependent Analysis) analyses, a TOF-MS scan from 330–1000 m/z was performed, followed by three rounds of MS/MS on the most intense singly or doubly charged precursors in each cycle. For targeted work, defined Product Ion Scans were created to isolate and fragment specific ions of interest with various collision energies (10–60 kV). Both positive and negative modes of ionization were used as appropriate.

MS/MS confirmation of reduction of dehydro-F420 species

To confirm the reduction of the PEP moiety in vitro assays were prepared in 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM GTP, 0.1 mM Fo, 1 mM PEP, 5 μM Mtb-FbiA, 6.5 μM Msg-FbiD, 10 mM DTT, 20 μM FMN, 0.2 mM NADH, 0.1 μM Ec-Fre, 2 μM Mtb-FbiB and 1 mM l-glutamate. To minimize futile oxidation of FMNH2 by oxygen the reaction mixture was repeatedly evacuated and purged with nitrogen and maintained under a nitrogen atmosphere. Samples were incubated at ambient temperature for up to 36 h and stopped by addition of 20 mM EDTA. Samples were desalted using Bond Elut C18 tips (Agilent Technologies) and eluted in 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile. Samples were injected onto a Q Exactive Plus (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 100 μLmin−1 with isocratic 50% B, where A was 10 mM ammonium acetate, pH 6.0, and B was 0.02% ammonia in methanol. Scans from 150–2250 m/z were performed and data-dependent MS/MS on targeted metabolites was done in both positive and negative modes.

Docking dehydro-F420-0 into FbiB C-terminal domain

Structures of FbiB C-terminal domain bound with F420-0 (4XOQ) and FMN (4XOO) were aligned in PyMOL and the ligands removed from the structures. Chemical dictionaries of dehydro-F420-0 and FMNH2 were prepared with AceDRG67 and built into the same molecule with COOT60 using the two density maps as appropriate. Dehydro-F420-0 was then reparametrized using the OPLS3e forcefield38 in Maestro (Schrödinger Release 2018-4: Maestro, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2018). The energy was minimized using the energy minimization function of Desmond (Schrödinger Release 2018-4: Desmond Molecular Dynamics System, D. E. Shaw Research, New York, NY, 2018; Maestro-Desmond Interoperability Tools, Schrödinger, New York, NY, 2018).

Production of F420 in Escherichia coli

The pF420 vector was transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) for expression. Cells were cultivated in M9 minimal media supplemented with chloramphenicol (25 µg mL−1) and tyrosine (18 μg mL−1) in 1 L shake flasks with 500 mL working volume at 28 °C. At an optical density (OD) of 0.60, 200 ng mL−1 of tetracycline was added to induce the expression of F420 biosynthesis pathway. After induction, cells were cultivated for at least 16 h. To test the expression of the F420 biosynthetic genes, cell pellets were lysed by resuspending to OD of 0.8 in buffer containing BugBuster (Novagen). Following centrifugation at 16,000 × g, proteins were resolved on a gel (BoltTM 4–12% Bis-Tris Plus, Invitrogen) for 1 h and visualized using Coomassie Brilliant Blue. For immunoblotting, proteins were transferred to a membrane (iBlot® 2 NC Regular Stacks, Invitrogen) using iBlot Invitrogen (25 V, 6 min). After staining and de-staining, the membrane was blocked with 3% skim milk solution and blotted with anti-FLAG antibodies conjugated with HRP (DYKDDDDK Tag Monoclonal Antibody, Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA1-91878-HRP, ×1000 dilution).

For detection of F420 in E. coli lysate by HPLC-FLD, cells were grown overnight in media containing 2.0% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 0.5% NaCl, 22 mM KH2PO4, 42 mM Na2HPO4, 100 ng mL−1 anhydrotetracycline, and 34 μg mL−1 chloramphenicol at 30 °C. Cells from 500 μL of culture were pelleted by centrifugation at 16,000 × g. Cells were re-suspended in 500μL of 50 mM Na2HPO4, pH 7.0, and lysed by boiling at 95 °C for 10 min. Cell debris was pelleted by centrifugation at 16,000 × g and filtered through a 0.22 μm PVDF filter. Analysis was conducted as described previously2. pSB1C3 containing only BBa_K145201 was used as a control.

Purification and analysis of Escherichia coli-produced F420

For F420 extraction, 1 L of cell culture was centrifuged at 5000 × g for 15 min. The cell pellet was re-suspended in 30 mL of 75% ethanol and boiled at 90 °C in a water bath for 6 min for cell lysis. The cell extract was again centrifuged at 5000 × g for 15 min to remove cell debris and the supernatant was lyophilized. The lyophilized cell extract was re-dissolved in 10 mL milli Q water centrifuged at 5000 × g for 15 min and the supernatant passed through 0.45 μm syringe filter (Millex-HV). The filtered cell extract was purified for F420 using a 5 mL HiTrap QFF column (GE Healthcare) as previously described41. The purified F420 solution was further desalted by passing it through C18 extract column (6 mL, HyperSep C18 Cartridges, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The C18 extract column was first equilibrated by passing through 10 mL of 100% methanol and 10 mL of milli Q. Afterwards, the F420 solution was passed through the C18 extract column, and F420 was eluted in 2 mL fraction of 20% methanol. The purified F420 solution was further concentrated in GeneVac RapidVap and re-dissolved in 500 μL of milli Q for further analysis and assays. To detect Fo accumulation in the media, it was filtered through a 0.45 μm syringe filter and purified directly on the C18 extract column as above.

UV and fluorescence spectra were collected on a Varian Cary 60 and a Varian Cary Eclipse, respectively, in a 10 mm QS quartz cell (Hellma Analytics). Samples were buffered to pH 7.5 with 50 mM HEPES and scanned from 250 to 600 nm. For fluorescence, the excitation wavelength was 420 nm and the emission scanned from 435 to 600 nm.

Activity assays with M. smegmatis and E. coli-derived F420 were conducted with M. smegmatis FGD expressed and purified as described previously15. Assays were performed in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 50 nM FGD, 5 μM F420, and 0–1000 μM glucose-6-phosphate using a SpectraMAX e2 plate reader. Activity was measured by following loss of F420 fluorescence at 470 nm. Apparent kcat and Km values were calculated using the GraphPad Prism 7.04 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA).

For malachite green reduction assays, cells were grown in 50 mL Falcon tubes containing 30 mL M9 minimal media, and supplemented with appropriate antibiotics at 28 °C. Cells were induced at OD600 of 0.6 by the addition of 200 ng μL−1 tetracycline and 0.2 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside. Cells were grown for an additional 6 h before adding malachite green to an initial OD615 of 0.26. Cultures were covered in foil and grown in the dark to prevent spontaneous decolorization. After overnight incubation, OD at 615 nm was measured with assays conducted in triplicate. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 7.04 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA).

2-PL synthesis

In the absence of a commercial source, 2-PL was chemically synthesized by a slight modification of the method of Ballou and Fischer68. Briefly, benzyl lactate was condensed with chlorodiphenyl phosphate in pyridine, with cooling, to give benzyldiphenylphosphoryl lactate. Hydrogenolysis of this material in 70% aqueous tetrahydrofuran over 10% Pd-C gave phospholactic acid as a colorless, viscous oil, which was characterized by proton, carbon, and phosphorus nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, and by MS. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 11.68 (br, 3H), 4.53 (m, 1H), 1.36 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 172.50 (d, JP–C = 0.05 Hz), 69.56 (d, JP–C = 0.04 Hz), 19.27 (d, JP–C = 0.04 Hz). 31P NMR (DMSO-d6) δ −1.64. APCI-MS found: [M + H]+ = 171.1, [M− H]− = 169.1.

Fo purification

Fo was purified from M. smegmatis culture medium over-expressing Mtb-FbiC as described previously41.

Genomic context analysis

A non-redundant CofE dataset of 4813 sequences was collected using the Pfam identifier PF01996 and the InterPro classifications IPR008225, IPR002847, and IPR023659. Archaeal CofE sequences were extracted from this dataset, resulting in a set of 1060 sequences that included representatives across 12 phyla: Crenarchaeota, Euryarchaeota, Thaumarchaeota, Candidatus Bathyarchaeota, Candidatus Diapherotrites, Candidatus Heimdallarchaeota, Candidatus Korarchaeota, Candidatus Lokiarchaeota, Candidatus Marsarchaeota, Candidatus Micrarchaeota, Candidatus Odinarchaeota, and Candidatus Thorarchaeota. The genomic context (10 upstream and 10 downstream genes) of each archaeal cofE was analyzed for the presence of a neighboring PF00881 domain with homology to the C-terminal domain of FbiB using the Enzyme Function Initiative—Genome Neighborhood Tool69.

Reporting Summary

Further information on experimental design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

References

Greening, C. et al. Physiology, biochemistry, and applications of F420- and Fo-dependent redox reactions. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 80, 451–493 (2016).

Ney, B. et al. The methanogenic redox cofactor F420 is widely synthesized by aerobic soil bacteria. ISME J. 11, 125–137 (2017).

Walsh, C. Naturally occurring 5-deazaflavin coenzymes: biological redox roles. Acc. Chem. Res. 19, 216–221 (1986).

Cheeseman, P., Toms-Wood, A. & Wolfe, R. S. Isolation and properties of a fluorescent compound, Factor420, from Methanobacterium strain M.o.H. J. Bacteriol. 112, 527–531 (1972).

Eirich, L. D., Vogels, G. D. & Wolfe, R. S. Proposed structure for coenzyme F420 from Methanobacterium. Biochemistry 17, 4583–4593 (1978).

Thauer, R. K., Kaster, A.-K., Seedorf, H., Buckel, W. & Hedderich, R. Methanogenic archaea: ecologically relevant differences in energy conservation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6, 579–591 (2008).

Lackner, G., Peters, E. E., Helfrich, E. J. N. & Piel, J. Insights into the lifestyle of uncultured bacterial natural product factories associated with marine sponges. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, E347–E356 (2017).

Jay, Z. J. et al. Marsarchaeota are an aerobic archaeal lineage abundant in geothermal iron oxide microbial mats. Nat. Microbiol. 3, 732–740 (2018).

Purwantini, E. & Mukhopadhyay, B. Conversion of NO2 to NO by reduced coenzyme F420 protects mycobacteria from nitrosative damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 6333–6338 (2009).

Gurumurthy, M. et al. A novel F420-dependent anti-oxidant mechanism protects Mycobacterium tuberculosis against oxidative stress and bactericidal agents. Mol. Microbiol. 87, 744–755 (2013).

Singh, R. et al. PA-824 kills nonreplicating Mycobacterium tuberculosis by intracellular NO release. Science 322, 1392–1395 (2008).

Wang, P., Bashiri, G., Gao, X., Sawaya, M. R. & Tang, Y. Uncovering the enzymes that catalyze the final steps in oxytetracycline biosynthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 7138–7141 (2013).

Coats, J. H., Li, G. P., Ming-ST, K. & Yurek, D. A. Discovery, production, and biological assay of an unusual flavenoid cofactor involved in lincomycin biosynthesis. J. Antibiot. 42, 472–474 (1989).

Ichikawa, H., Bashiri, G. & Kelly, W. L. Biosynthesis of the thiopeptins and identification of an F420H2-dependent dehydropiperidine reductase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 10749–10756 (2018).

Taylor, M. C. et al. Identification and characterization of two families of F420H2-dependent reductases from Mycobacteria that catalyse aflatoxin degradation. Mol. Microbiol. 78, 561–575 (2010).

Greening, C. et al. Mycobacterial F420H2-dependent reductases promiscuously reduce diverse compounds through a common mechanism. Front. Microbiol. 8, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.01000 (2017).

Graupner, M., Xu, H. & White, R. H. Characterization of the 2-phospho-l-lactate transferase enzyme involved in coenzyme F420 biosynthesis in Methanococcus jannaschii. Biochemistry 41, 3754–3761 (2002).

Choi, K.-P., Bair, T. B., Bae, Y.-M. & Daniels, L. Use of transposon Tn5367 mutagenesis and a Nitroimidazopyran-based selection system to demonstrate a requirement for fbiA and fbiB in coenzyme F420 biosynthesis by Mycobacterium bovis BCG. J. Bacteriol. 183, 7058–7066 (2001).

Forouhar, F. et al. Molecular insights into the biosynthesis of the F420 coenzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 11832–11840 (2008).

Bashiri, G. et al. Elongation of the poly-γ-glutamate tail of F420 requires both domains of the F420:γ-glutamyl ligase (FbiB) of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 6882–6894 (2016).

Li, H., Graupner, M., Xu, H. & White, R. H. CofE catalyzes the addition of two glutamates to F420-0 in F420 coenzyme biosynthesis in Methanococcus jannaschii. Biochemistry 42, 9771–9778 (2003).

Graupner, M. & White, R. H. Biosynthesis of the phosphodiester bond in coenzyme F420 in the Methanoarchaea. Biochemistry 40, 10859–10872 (2001).

Guerra-Lopez, D., Daniels, L. & Rawat, M. Mycobacterium smegmatis mc2 155 fbiC and MSMEG_2392 are involved in triphenylmethane dye decolorization and coenzyme F420 biosynthesis. Microbiology 153, 2724–2732 (2007).

Rifat, D. et al. Mutations in Rv2983 as a novel determinant of resistance to nitroimidazole drugs in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Preprint at http://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/457754 (2018).

Grochowski, L. L., Xu, H. & White, R. H. Identification and characterization of the 2-phospho-l-lactate guanylyltransferase involved in coenzyme F420 biosynthesis. Biochemistry 47, 3033–3037 (2008).

Cole, S. T. et al. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature 393, 537–544 (1998).

Ash, D. E., Goodhart, P. J. & Reed, G. H. ATP-dependent phosphorylation of α-substituted carboxylic acids catalyzed by pyruvate kinase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 228, 31–40 (1984).

Collard, F. et al. A conserved phosphatase destroys toxic glycolytic side products in mammals and yeast. Nat. Chem. Biol. 12, 601–607 (2016).

Walker, S. R., Cumming, H. & Parker, E. J. Substrate and reaction intermediate mimics as inhibitors of 3-deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonate 7-phosphate synthase. Org. Biomol. Chem. 7, 3031–3035 (2009).

Izui, K., Matsuda, Y., Kameshita, I., Katsuki, H. & Woods, A. E. Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase of Escherichia coil. Inhibition by various analogs and homologs of phosphoenolpyruvate. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 94, 1789–1795 (1983).

Bennett, B. D. et al. Absolute metabolite concentrations and implied enzyme active site occupancy in Escherichia coli. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5, 593–599 (2009).

Tan, K., Du, J., Clancy, S. & Joachimiak, A. The crystal structure of a hypothetical protein MM_2497 from Methanosarcina mazei Go1. Protein Data Bank https://doi.org/10.2210/pdb2I5E/pdb (2006).

Nowak, T. & Mildvan, A. S. Stereoselective interactions of phosphoenolpyruvate analogues with phosphoenolpyruvate-utilizing enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 245, 6057–6064 (1970).

Lake, M. W., Temple, C. A., Rajagopalan, K. V. & Schindelin, H. The crystal structure of the Escherichia coli MobA protein provides insight into molybdopterin guanine dinucleotide biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 40211–40217 (2000).

Nocek, B. et al. Structure of an amide bond forming F420:γ-glutamyl ligase from Archaeoglobus fulgidus—a member of a new family of non-ribosomal peptide synthases. J. Mol. Biol. 372, 456–469 (2007).

Akiva, E., Copp, J. N., Tokuriki, N. & Babbitt, P. C. Evolutionary and molecular foundations of multiple contemporary functions of the nitroreductase superfamily. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, E9549–E9558 (2017).

FieschiF.., NivièreV.., FrierC.., DécoutJ.-I.. & FontecaveM.. The mechanism and substrate specificity of the Nadph:Flavin oxidoreductase from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 30392–30392 (1995).

Harder, E. et al. OPLS3: a force field providing broad coverage of drug-like small molecules and proteins. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 12, 281–296 (2016).

Salis, H. M., Mirsky, E. A. & Voigt, C. A. Automated design of synthetic ribosome binding sites to control protein expression. Nat. Biotechnol. 27, 946–950 (2009).

Spang, A. et al. Complex archaea that bridge the gap between prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Nature 521, 173–179 (2015).

Bashiri, G., Rehan, A. M., Greenwood, D. R., Dickson, J. M. J. & Baker, E. N. Metabolic engineering of cofactor F420 production in Mycobacterium smegmatis. PLoS ONE 5, e15803 (2010).

Isabelle, D., Simpson, D. R. & Daniels, L. Large-scale production of coenzyme F420-5,6 by using Mycobacterium smegmatis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68, 5750–5755 (2002).

Ney, B. et al. Cofactor tail length modulates catalysis of bacterial F420-dependent oxidoreductases. Front. Microbiol. 8, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.01902 (2017).

Jirapanjawat, T. et al. The redox cofactor F420 protects mycobacteria from diverse antimicrobial compounds and mediates a reductive detoxification system. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 82, 6810–6818 (2016).

Wang, F. et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis dihydrofolate reductase is not a target relevant to the antitubercular activity of isoniazid. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54, 3776–3782 (2010).

Andersen, K. R., Leksa, N. C. & Schwartz, T. U. Optimized E. coli expression strain LOBSTR eliminates common contaminants from His-tag purification. Proteins 81, 1857–1861 (2013).

Studier, F. W. Protein production by auto-induction in high-density shaking cultures. Protein Expr. Purif. 41, 207–234 (2005).

Ahmed, F. H. et al. Sequence–structure–function classification of a catalytically diverse oxidoreductase superfamily in mycobacteria. J. Mol. Biol. 427, 3554–3571 (2015).

Bashiri, G., Squire, C. J., Baker, E. N. & Moreland, N. J. Expression, purification and crystallization of native and selenomethionine labeled Mycobacterium tuberculosis FGD1 (Rv0407) using a Mycobacterium smegmatis expression system. Protein Expr. Purif. 54, 38–44 (2007).

Espah Borujeni, A., Channarasappa, A. S. & Salis, H. M. Translation rate is controlled by coupled trade-offs between site accessibility, selective RNA unfolding and sliding at upstream standby sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 2646–2659 (2014).

Canton, B., Labno, A. & Endy, D. Refinement and standardization of synthetic biological parts and devices. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 787–793 (2008).

Kabsch, W. XDS. Acta Crystallogr. D 66, 125–132 (2010).

Evans, P. Scaling and assessment of data quality. Acta Crystallogr. D 62, 72–82 (2006).

Winn, M. D. et al. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr. D 67, 235–242 (2011).

Panjikar, S., Parthasarathy, V., Lamzin, V. S., Weiss, M. S. & Tucker, P. A. Auto-Rickshaw: an automated crystal structure determination platform as an efficient tool for the validation of an X-ray diffraction experiment. Acta Crystallogr. D 61, 449–457 (2005).

Schneider, T. R. & Sheldrick, G. M. Substructure solution with SHELXD. Acta Crystallogr. D 58, 1772–1779 (2002).

Terwilliger, T. Maximum-likelihood density modification. Acta Crystallogr. D 56, 965–972 (2000).

Perrakis, A., Morris, R. & Lamzin, V. S. Automated protein model building combined with iterative structure refinement. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6, 458–463 (1999).

Adams, P. D. et al. PHENIX: building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D 58, 1948–1954 (2002).

Emsley, P. & Cowtan, K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D 60, 2126–2132 (2004).

Murshudov, G. N. et al. REFMAC5 for the refinement of macromolecular crystal structures. Acta Crystallogr. D 67, 355–367 (2011).

Joosten, R. P., Long, F., Murshudov, G. N. & –Perrakis, A. The PDB_REDO server for macromolecular structure model optimization. IUCrJ 1, 213–220 (2014).

McCoy, A. J. et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40, 658–674 (2007).

Leaver-Fay, A. et al. MolProbity: all-atom contacts and structure validation for proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W375–W383 (2007).

Taly, J.-F. et al. Using the T-Coffee package to build multiple sequence alignments of protein, RNA, DNA sequences and 3D structures. Nat. Protoc. 6, 1669–1682 (2011).

Gouet, P. & Robert, X. Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, W320–W324 (2014).

Long, F. et al. AceDRG: a stereochemical description generator for ligands. Acta Crystallogr. D 73, 112–122 (2017).

Ballou, C. E. & Fischer, H. O. L. A new synthesis of 2-phosphoryl-d-glyceric acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 76, 3188–3193 (1954).

Gerlt, J. A. Genomic enzymology: web tools for leveraging protein family sequence–function space and genome context to discover novel functions. Biochemistry 56, 4293–4308 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We thank Assoc. Prof. Chris Squire, Dr. Carol Hartley, Dr. Andrew Warden, and Dr. Matthew Taylor for helpful discussions, Dr. Adam Carroll and Dr. Thy Truong for technical assistance. This research is supported by a Sir Charles Hercus Fellowship (G.B.), an NHMRC New Investigator Grant (C.G.; 1142699), an ARC DECRA Fellowship (C.G.; DE170100310), the Health Research Council of New Zealand (E.N.B.), an AGRTP Scholarship (J.A.), the Australian Research Council, and the National Health and Medical Research Council (C.J.J.). Crystal data collection was undertaken on the MX1 beamline at the Australian Synchrotron (Clayton, VIC, Australia). Access to the Australian Synchrotron was supported by the New Zealand Synchrotron Group Ltd.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.A. performed experiments, analyzed results, and co-wrote the manuscript; E.N.M.J., M.V.S., J.C., S.M.S., S.S., B.P., M.M., and N.T. performed experiments and analyzed results; B.N. conceived project, performed experiments, and analyzed results; C.G. and E.N.B. conceived project, designed experiments, analyzed results, and co-wrote the manuscript; C.S. designed experiments, analyzed results, and co-wrote the manuscript; G.B. and C.J.J. conceived project, designed experiments, performed experiments, analyzed results, and co-wrote the manuscript. All authors provided feedback on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Journal peer review information: Nature Communications thanks Martin Warren and the other anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bashiri, G., Antoney, J., Jirgis, E.N.M. et al. A revised biosynthetic pathway for the cofactor F420 in prokaryotes. Nat Commun 10, 1558 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09534-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09534-x

This article is cited by

-

Poly-γ-glutamylation of biomolecules

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Flavin-enabled reductive and oxidative epoxide ring opening reactions

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Improved production of the non-native cofactor F420 in Escherichia coli

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Co-occurrence of enzyme domains guides the discovery of an oxazolone synthetase

Nature Chemical Biology (2021)

-

Metabolic engineering of roseoflavin-overproducing microorganisms

Microbial Cell Factories (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.