Abstract

Non-aqueous lithium-oxygen batteries cycle by forming lithium peroxide during discharge and oxidizing it during recharge. The significant problem of oxidizing the solid insulating lithium peroxide can greatly be facilitated by incorporating redox mediators that shuttle electron-holes between the porous substrate and lithium peroxide. Redox mediator stability is thus key for energy efficiency, reversibility, and cycle life. However, the gradual deactivation of redox mediators during repeated cycling has not conclusively been explained. Here, we show that organic redox mediators are predominantly decomposed by singlet oxygen that forms during cycling. Their reaction with superoxide, previously assumed to mainly trigger their degradation, peroxide, and dioxygen, is orders of magnitude slower in comparison. The reduced form of the mediator is markedly more reactive towards singlet oxygen than the oxidized form, from which we derive reaction mechanisms supported by density functional theory calculations. Redox mediators must thus be designed for stability against singlet oxygen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lithium-oxygen (Li-O2) batteries have a very high theoretical capacity, but are still far from practical use1,2. Among the many problems associated with Li-O2 batteries, the most highlighted issues are their high charge overpotential and side reactions3,4,5,6,7,8. The high charge overpotential due to the difficulty of decomposing the discharge product, lithium peroxide (Li2O2), severely increases side reactions that decompose the electrolyte and electrode and lead to poor rechargeability, increasing charging overpotential, and a build-up of parasitic products during cycling9,10,11,12.

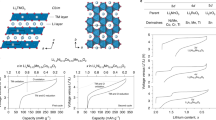

To mitigate the high overpotentials and associated side reactions, catalysts have been utilized to facilitate Li2O2 oxidation during recharging7,11,12,13,14. The many reported catalysts for decomposing Li2O2 can be classified into two types. The first type, solid catalysts, may enhance Li2O2 decomposition by enhancing charge transport within Li2O212,15 or delitihiation kinetics13,16. However, solid catalysts act only near their surface and may not only accelerate the decomposition of Li2O2 but also the undesired side reactions involving the electrode and electrolyte12,14,17 The second type, redox mediators (RMs), are soluble catalysts in the electrolyte to chemically decompose Li2O2. They are oxidized at the porous electrode substrate and then diffuse to Li2O2, which decomposes to Li+ and O2 by reforming the original reduced state18,19,20,21,22. In principle, mediators with a redox potential beyond the thermodynamic potential of the O2/Li2O2 couple (2.96 V vs. Li/Li+) allow the cell to be recharged with nearly zero overpotential18,19,20,21,22,23. Therefore, many different redox mediators have recently been studied, with a focus on finding the lowest possible voltage and fastest kinetics7,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28. They have been shown to enable recharging at a potential close to their redox potential at rates far greater than those that can be achieved without a mediator.

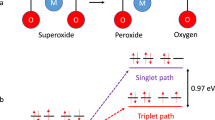

However, the catalytic effect of RMs deteriorates with repeated cycling. Reported reasons for this deterioration include side reactions with the anode when unprotected lithium metal is used29,30,31,32 and reaction with the electrolyte18,21,22. However, even when both of these effects are excluded by protecting the anode with, e.g., a solid electrolyte and choosing mediators that are inert towards the electrolyte, the RMs still gradually degrade and the energy efficiency decreases. To solve these problems, the SOMO energy of the oxidized mediator must not be lower than the HOMO of the electrolyte solvent22. However, even when the lithium metal and the selected RM were completely separated, the catalytic activity of the RM still declined. This implies that the RM must participate in other side reactions with reactive species at the cathode, which have not yet been clarified21,33. Meanwhile, it is well established that reactive oxygen species cause electrolyte decomposition. Superoxide (O2−) and Li2O2 have traditionally been assumed to cause the majority of side reactions due to their nucleophilicity, basicity, and/or radical nature, even though theoretical calculations suggest unfavorable reaction energies1,34,35,36,37,38,39,40. Only recently has it been demonstrated that singlet oxygen (1O2), the first excited state of ground state triplet oxygen, is actually the main cause of parasitic reactions during the cycling of metal-O2 batteries41,42,43,44,45.

Here we assess the reactivity of organic RM’s towards dissolved oxygen (O2), potassium superoxide (KO2), Li2O2, and 1O2 using quantitative UV–Vis analysis and 1H-NMR. We demonstrate the predominant cause for RM deactivation to be 1O2. Reactions with the other oxygen species are, if at all detectable, comparatively negligible. The reduced state of the RMs is markedly more reactive than the oxidized state due to the electrophilic nature of 1O2. The deactivation mechanisms can therefore be proposed to involve “ene” and “diene” cycloadditions and oxidation of the sulfur; these mechanisms are supported by density functional theory (DFT) calculations and analysis of decomposition products. The obtained reaction energies agree well with the observed kinetics. Only by clearly identifying the reason for the deactivation of RMs, a key active material in Li-O2 batteries, can more reversible and highly efficient Li-O2 batteries be achieved. Their side reactions with cell components caused by 1O2 thus need to be considered comprehensively.

Results

Spectroscopic proof for mediator deactivation by 1O2

Redox mediators may be deactivated by any of the potentially reactive species that appear during cycling of the cell, including O2, O2–, Li2O2, and, as recently revealed, the highly reactive 1O2. We thus investigated the stability of a selection of redox mediators towards these species. Among the many kinds of RMs studied so far, we chose tetrathiafulvalene (TTF) and dimethylphenazine (DMPZ) as representative redox mediators, since TTF was amongst the first RMs reported and DMPZ has one of the lowest charge potentials reported and has been shown to be compatible with glyme electrolyte as it does not facilitate its oxidative decomposition based on DFT calculations and experimental verification22.

The RMs were dissolved in tetraethylene glycol dimethyl ether (TEGDME) at a concentration (60 µM) suitable for UV–Vis spectroscopy. After measuring the fresh solutions, the mediators in solution were then exposed to O2, KO2, Li2O2, and 1O2 (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1). For the first three, the contact time was 24 h, after which the electrolyte was reexamined. In the case of KO2, an excess amount of 18-crown-6 was added to dissolve the KO2 and thus enhance its reactivity. Dissolved oxygen (O2), O2–, and Li2O2 had no appreciable effect on the DMPZ or TTF concentration even after 24 h (Fig. 1a–e and Supplementary Fig. 1). Additionally, the NMR spectra of the electrolyte solutions after this time show negligible changes (Supplementary Fig. 2). These results are consistent with those of a previous study that reported the stability of DMPZ against O2– (see ref. 22).

Stability of reduced redox mediators against oxygen species. UV–Vis spectra of DMPZ (a–c) and TTF (d–f) in 0.1 M LiTFSI/TEGDME electrolyte before and after exposure to O2 (a, d), KO2 (b, e), and 1O2 (c, f). The concentrations of DMPZ and TTF were 60 µM each in their respective solutions. O2 and KO2 (together with an excess of 18-crown-6) were kept in contact with the RMs for 24 h. 1O2 was photogenerated in the O2-saturated solution using 1 µM palladium(II) meso-tetra(4-fluorophenyl)-tetrabenzoporphyrin and illumination at 643 nm, and the spectra were measured after the illumination times indicated. The spectrum of the sensitizer has been subtracted from c and f

To investigate the stability of the RMs against 1O2, we produced 1O2 photochemically by illuminating O2-saturated mediator solutions containing 1 µM of the photosensitizer palladium(II) meso-tetra(4-fluorophenyl)-tetrabenzoporphyrin (Pd4F) at a wavelength of 643 nm46. Photosensitization transfers energy from absorbed light to triplet oxygen47. The process is initiated by the excitation of the photosensitizer from its S0 ground state to its excited singlet state Sn, which then relaxes to the lowest excited singlet state S1 and yields the triplet state T1 via intersystem crossing (ISC). T1 then transfers the energy to 3O2 to form 1O2. Unlike O2, KO2, and Li2O2, we found that 1O2 decreased the main absorbance peaks of the RMs within several hours for DMPZ and within seconds for TTF (Fig. 1c–f). Simultaneously, new products appeared with red-shifted absorption bands. 1H-NMR analyses of the solutions after illumination show the corresponding disappearance of the mediators, Supplementary Fig. 3. The NMR intensity of DMPZ decreased by ~40%, in agreement with the similar decrease observed in its UV absorbance (Fig. 1c). For TTF, the NMR spectra (Supplementary Fig. 3b) show the concurrent appearance of new products. Of note, the integral of all the new products are much less than the mediators at the start. This means that the products still visible in the NMR do not represent all products the mediators are decomposing to. They may form inorganic products or evolve as gases as ultimate products of oxidative decomposition reactions discussed later. Together, these data demonstrate the drastically higher reactivity of the RMs towards 1O2 than any of the other oxygen species.

Figure 2 shows the evolution of the main absorbances of the RMs with time when in contact with 1O2. 1O2 caused DMPZ to decay to two-thirds of its initial value within 3 h and TTF to be fully decomposed within about half a minute. TTF thus degrades much more rapidly than DMPZ. Although we do not completely rule out the reactivity of the RMs with O2, KO2, or Li2O2, it is clear from Fig. 1 that the RMs are much more reactive with 1O2. Overall, the data demonstrate that RM deactivation is overwhelmingly associated with 1O2, which has been shown to be formed during both the discharging and charging of the cell41,43,44.

Reaction rate of redox mediators with singlet oxygen. Change in absorbance over time normalized to the initial value upon exposure to 1O2 for DMPZ (a) and TTF (b) as extracted from the spectra in Fig. 1 at the respective peak maxima

Reactivity between 1O2 and oxidized redox mediators

Singlet oxygen (1O2) is known to react with electron-rich organic substrates containing C=C double bonds via so-called “ene” or “diene” reactions driven by the electrophilic nature of 1O248,49,50,51. The presence of ene and diene motifs in TTF and DMPZ, respectively, makes these mechanisms likely routes of attack leading to RM decomposition, as examined later. Given the electrophilic nature of 1O2, the question arises whether the oxidized forms of the mediators would show similarly strong reactivity. To test this, we oxidized the mediators electrochemically (see Methods and Supplementary Fig. 6 for details), exposed them to in situ generated 1O2 as before, and followed the mediator concentration using UV–Vis (Fig. 3). Considering first DMPZ+, the spectra show a gradual decrease of the main peaks at ~370 and 450 nm together with increasing absorbance at around 400 and 500 nm. This indicates the gradual decomposition of DMPZ+, albeit at a markedly lower rate than DMPZ (Fig. 1c), accompanied by the formation of new products. After 3 h of illumination, >95% of the initial DMPZ+ remained, as compared to only ~65% of the DMPZ at the same time point. The relatively slower reactivity of DMPZ+ compared to DMPZ can equally be seen by comparing Fig. 2a with 3b. However, regardless of the relative stability of DMPZ+ in the presence of 1O2, it is clear that the DMPZ/DMPZ+ redox couple is degraded as a whole by 1O2, because DMPZ reacts strongly.

Stability of oxidized redox mediators against singlet oxygen. UV-Vis spectra of DMPZ+ (a) and TTF+ (c) upon exposure to 1O2 as well as the normalized absorbance of DMPZ+ (b) and TTF+ (d) vs. time, as extracted from the positions indicated. DMPZ+ or TTF+ were generated by electrochemically oxidizing 0.02 M DMPZ or TTF, respectively in TEGDME electrolytes containing 0.1 M LiTFSI, followed by extraction into TEGDME to form a 250 µM solution. 1O2 was photogenerated in the O2-saturated solution using 1 µM palladium(II) meso-tetra(4-fluorophenyl)-tetrabenzoporphyrin and illumination at 643 nm, and the spectra were measured after the illumination times indicated. The spectrum of the sensitizer has been subtracted from a and c

Turning to TTF+, the analogous experiment is shown in Fig. 3c, d. The spectra do not simply scale over the full wavelength range, but instead show a rapid decrease around 300 nm and a more gradual decrease elsewhere, which indicates the degradation of TTF+ together with the formation of new products. TTF+ is degraded to about two-thirds of its initial concentration within 10 min, whereas TTF was already fully decomposed after only ~30 s (Fig. 1c). The rate of TTF+ decomposition is roughly 150 times lower than that of TTF. As with the DMPZ/DMPZ+ couple, the reduced form TTF reacts much faster than the oxidized form TTF+. Overall, TTF/TTF+ reacts much faster with 1O2 than DMPZ/DMPZ+ regardless of the oxidation state. In all cases, the reaction with 1O2 clearly dominates the possible reactions with the other oxygen species (O2, O2−, and Li2O2).

The marked difference in reactivity towards 1O2 between the reduced and oxidized forms points to reaction mechanisms that are governed by the electron-richness of the substrate. The literature on the reactivity of 1O2 with organic substrates most commonly indicates an organic peroxide material as an initial product52. Thus, 1O2 produces R–OOH, R•, and R–OO• moieties; these radicals can propagate to generate other reactive intermediates and various by-products, particularly in the presence of O253,54. Therefore, the RMs will lose their redox activity after initial reaction with 1O2 due to the instability of the initial products.

Mechanisms and energetics of reactions between RM and 1O2

In Figs. 4, 5, we propose reactions of DMPZ/DMPZ+ and TTF/TTF+, respectively, with 1O2 based on published mechanisms for the reaction of 1O2 with dienes, enes, and sulfides, respectively48,49,50,51,55,56,57. We also carried out DFT calculations of the free energies of these reactions and calculated barriers for the reactions by finding transition states to judge their likelihood. The DFT energies of neutrals and cations were calculated at the B3LYP/6–31+G* level of theory58 for their geometries optimized at the B3LYP/6–31G* level. Vibrational frequencies were calculated to ensure that the optimized geometries were local minima and were used to determine the zero-point energies. The energies were adjusted for the well-known error in the 1O2 at the DFT level compared to triplet O2. In the case of the B3LYP/6–31+G* energies, this correction is 0.98 eV. The solution phase effects were included using a PCM continuum model59 with a dielectric constant of 7.2. The reactions considered, the optimized structures of the products, and the reaction energies are shown in Fig. 4.

Considering first DMPZ, 1O2 was reported to react with a diene via a Diels-Alder type [4 + 2] cycloaddition to yield endoperoxides. The electrophilicity of 1O2 increases the reactivity of 1O2 in the [4 + 2] cycloaddition towards aromatic compounds having a high electron density50. Thus, in general the RM will react more easily with 1O2 than the RM+, as seen in the experimental data in Figs. 1–3. [4 + 2] cycloaddition at H-substituted aromatic carbons is much slower than at carbons with electron-donating groups such as C6H5, CH3, or OCH3, and thus, cycloaddition to 9,10-disubstituted anthracenes is favored over the other rings, and the reactivity follows the order C6H5 < CH3 < OCH350. The subsequent reactions have been reported to be either cycloreversion or O–O bond cleavage, with the latter being preferred in the absence of substituents50. Translating this to DMPZ, the electron donation by the two amines may allow for appreciable reactivity at the 1,4 position for [4 + 2] cycloaddition to give the endoperoxide 5 (Fig. 4). Another possible route of attack is at the π-bond adjacent to the amine to yield the dioxetane-type product 6. However, we could not locate the corresponding biradical products that would form upon O–O cleavage in 5 as suggested for the decomposition of an endoperoxide50. [4 + 2] cycloaddition at DMPZ+ may also give the endoperoxide 7. However, all these reactions are energetically rather unfavorable with large reaction barriers well above 1 eV. Oxidation to DMPZ+ appears to reduce the electron density at the 1,4 positions in a manner resulting in inferior reaction thermodynamics, which is also reflected in the even higher reaction barrier for DMPZ compared with DMPZ+ and seen in the experimentally observed faster reactivity of the former compared to the latter.

The reaction of 1O2 with enes is the subject of longstanding mechanistic investigations and was found to be a complicated process with various possible intermediates such as a diradical, zwitterion, perepoxide, or dioxetane48,49,51. Typically, reactions of 1O2 with substrates that contain an H at the α-C, e.g., CH3–CH=CH2, have been investigated, and found to lead to a shift of the double bond to form the hydroperoxide CH2=CH–CH2–OOH by H-abstraction at the methyl group48,49. The π-bonds of TTF, however, are all terminated by S, which may result in the reactive intermediates attacking further molecules. The ene position in the TTF rings is one possible position for 1O2 attack, for which we found three possible head-on products, 8–10, and the dioxetane 11. While an analogous biradical could not be located for DMPZ, we were able to find the biradical 9 for TTF. The other possible point of attack is at the central C=C bond to form the dioxetane product 12. Both reactions that lead to the dioxetanes are thermodynamically favorable, as they are exothermic and have rather small activation barriers of ~0.4–0.7 eV. Dioxetanes are known to undergo decomposition to the related carbonyl compounds by cleaving the C–C bond60. Reported mechanisms involve either [2 + 2] cycloelimination or a radical mechanism61. The sensitized photooxygenation of a related compound has been reported to undergo such cleavage to form the corresponding dithiocarbonate. The corresponding mechanism with TTF is shown in Supplementary Fig. 4 to form 1,3-dithiol-2-one. It is clearly seen in the NMR as the major newly formed decomposition product with a peak at 7.1 ppm. However, all the NMR visible products together after photooxygenation only equate to 40% of the initial TTF of which 28% are 1,3-dithiol-2-one. Hence, 1,3-dithiol-2-one decomposes further with 1O2. There are minor peaks at ~5.8 and 1.2 ppm which we could not identify, but which are by far not accounting for all lost TTF. Alternative pathways where the organic sulfides react to give the corresponding peroxysulfoxides, sulfoxides, or sulfones 13–1655,56,57 appear less likely considering the high activation energies. Reactions with TTF+ could yield the product 17 through attack at the ring position or 18 through attack at the central position, with the latter being somewhat more favorable. For both mediators, the reactions of 1O2 with the mediator cation are less favorable, because we find that 1O2 forms molecular complexes with the cations that are more stable than the respective products of 1O2 insertion.

Overall, the reaction energies in Figs. 4, 5 indicate that the TTF species have smaller barriers to reaction with 1O2 than the DMPZ species, and thus will undergo faster reactions. This is consistent with the experimental studies of the reaction rates (Figs. 2, 3). We also find that the oxidized TTF has a higher reaction barrier than neutral TTF. This is consistent with the experimental finding that neutral TTF undergoes reaction with 1O2 more readily than the oxidized state of TTF. Little difference was found between the reaction barriers of neutral DMPZ and DMPZ+, although we were not able to locate a structure for the biradical of DMPZ, which could be lower in energy than the closed shell singlet.

Discussion

The results of this study have multiple implications for required research directions in Li-O2 cells towards developing practical energy storage devices. First, generally, the previous paradigm that stability of cell components against O2– and Li2O2 were of prime importance needs to shift towards additionally and even more importantly stability against 1O2. This concerns both studies on how materials degrade and on making more stable materials. Second, redox mediation is now widely accepted to be key for Li-O2 batteries to achieve maximum energy density and efficiency by far higher rates than possible without the mediator. The fact that we have shown that mediators can have very different susceptibility to decompose with 1O2 spurs hope that even more stable mediators will be found. Third, the computational results that nicely reproduce the trend in reactivity between the investigated mediators and between the reduced and oxidized states suggest that computational screening will be a very effective tool to preselect candidate mediators. Fourth, even the best now available mediators may not be sufficiently stable for long term operation in presence of 1O2. Therefore, additional means of counteracting degradation will likely be required. These may be chemical traps that more rapidly react with 1O2 than other cell components, or, preferably, physical quenchers which catalyze the decay from 1O2 to triplet oxygen43.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that the widely observed gradual deactivation of RMs in Li-O2 cells is predominantly caused by the decomposition of the RM by 1O2. Thus, 1O2-induced decomposition is the main reason for the decreasing catalytic effect of organic RMs during the cycling of Li-O2 batteries, even when they are protected from the lithium metal. The reduced forms of the RMs are particularly vulnerable to 1O2 attack because of the electrophilic nature of 1O2. At the same time, we have shown that there are vast differences between the reactivities of different organic RMs, which spurs hope that RMs can be designed to be sufficiently stable for long-term operation. Therefore, the stability of RMs against 1O2 must be considered, and RMs that are stable against 1O2 attack must be found. Additionally, other measures to suppress 1O2 formation by, e.g., quenchers are warranted.

Methods

Chemicals

Tetraethylene glycol dimethyl ether (TEGDME, 99%), dimethoxy ethane (DME, 99%), bis(trifluoromethane)sulfonimide lithium salt (LiTFSI, 99.95%), dimethylphenazine (DMPZ), tetrathiafulvalene (TTF), potassium superoxide (KO2), lithium peroxide (Li2O2, 90%), 1,4,7,10,13,16-hexaoxacyclooctadecane (18-crown-6, ≥99%), acetonitrile (anhydrous, 99.8%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The lithium salt was dried in a vacuum oven for 3 days at 140 °C. The solvents were purified by distillation and further dried over activated molecular sieves. Palladium(II) meso-tetra(4-fluorophenyl)tetrabenzoporphyrin (Pd4F) was synthesized as a sensitizer for 1O2 generation according to a previously reported procedure46. Lithium iron phosphate (LiFePO4) was purchased from MTI Corporation and used to prepare partially delithiated LiFePO4 (Li1−xFePO4) according to a previously reported procedure62.

Electrochemical methods

Electrolytes containing the oxidized RMs (RM+) were prepared by electrochemical oxidation of the RMs. The electrochemical cells used to oxidize the RMs were based on a Swagelok design (see Supplementary Fig. 7). A porous carbon paper cathode (Freudenberg H2315), glass fiber separator (Whatman GF/F), and Li1−xFePO4 counter electrode were used in the cells, which contained 50 μL electrolyte (0.02 M RM (DMPZ or TTF) and 0.1 M LiTFSI in TEGDME). The working electrodes and separators were washed and dried at 120 °C for 24 h under vacuum prior to use. The Li1−xFePO4 counter electrodes were made by mixing partially delithiated active material with Super P and PTFE in the ratio 8:1:1(m/m/m) from which free-standing electrodes were obtained. The electrodes were vacuum dried at 200 °C for 24 h. The cells were assembled and operated using a MPG-2 potentiostat/galvanostat (BioLogic) in an Ar-filled glovebox. The cell containing DMPZ was charged at 100 µA to a potential of 3.5 V vs. Li/Li+. The cell containing TTF was charged at 100 µA to 3.7 V vs. Li/Li+.

UV–Vis and 1H-NMR analysis

UV–Vis absorption spectra were recorded on a Cary 50 UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Varian). For stability measurements against O2, KO2, Li2O2, and 1O2 TEGDME electrolytes containing 0.1 M LiTFSI and 60 µM RM were used. For measuring O2 stability, 2 mL of the electrolyte were saturated with a stream of pure O2 via a septum for 10 min and then the solution further stirred for 24 h in a closed 20 mL vial with pure O2 headspace. For measuring stability against O2–, 14.2 mg KO2 and 52.9 mg 18-crown-6 (excess amount) were stirred in 2 mL of the electrolyte. For measuring stability against Li2O2, 1 mg Li2O2 were stirred in 2 mL of the electrolyte. The photochemical generation of 1O2 was achieved by in situ photogeneration with the sensitizer Pd4F. A 3O2-saturated TEGDME electrolyte containing 0.1 M LiTFSI and 60 µM RM that contained 1 µM of the sensitizer was irradiated with a red light-emitting diode light source (OSRAM, 643 nm, 7 W). During the measurement, the electrolytes were stirred to ensure uniform RM and oxygen species concentration using a small size magnetic bar in the cuvette. The sample preparation for the oxidized RMs was carried out using the same procedure as for the RMs with the additional pre-oxidation process described above. After oxidation, the cells were disassembled immediately in the glovebox and the RM+-containing electrolytes were extracted with TEGDME to obtain a total of 4 mL solution. The extract had thus a concentration of 250 µM RM+, but likely somewhat less since the extraction from the porous media will be slow. One micrometer sensitizer was added for the following experiments with 1O2. For the 1H-NMR measurements, samples were prepared as before but with a concentration of 1 mg RM in 1 mL DME. DME was used to allow for solvent evaporation. After the contact time with the oxygen species (O2, KO2, Li2O2, and 1O2) the solvent was evaporated at room temperature under vacuum, the residue dissolved in 0.8 mL DMSO-d6 and subjected to 1H-NMR measurement on a Bruker AVANCE III 300 MHz spectrometer. The DMSO peak is taken as internal reference for quantitative comparison of spectra.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Aurbach, D., McCloskey, B. D., Nazar, L. F. & Bruce, P. G. Advances in understanding mechanisms underpinning lithium–air batteries. Nat. Energy 1, 16128 (2016).

Vegge, T., Garcia-Lastra, J. M. & Siegel, D. J. Lithium–oxygen batteries: At a crossroads?. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 6, 100–107 (2017).

Younesi, R., Hahlin, M., Björefors, F., Johansson, P. & Edström, K. Li-O2 battery degradation by lithium peroxide (Li2O2): a model study. Chem. Mater. 25, 77–84 (2012).

Papp, J. K. et al. Poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF) binder degradation in Li–O2 batteries: a consideration for the characterization of lithium superoxide. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 8, 1169–1174 (2017).

McCloskey, B. D., Burke, C. M., Nichols, J. E. & Renfrew, S. E. Mechanistic insights for the development of Li-O2 battery materials: addressing Li2O2 conductivity limitations and electrolyte and cathode instabilities. Chem. Commun. 51, 12701–12715 (2015).

McCloskey, B. D. et al. Combining accurate O2 and Li2O2 assays to separate discharge and charge stability limitations in nonaqueous Li–O2 batteries. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 4, 2989–2993 (2013).

McCloskey, B. D. & Addison, D. A viewpoint on heterogeneous electrocatalysis and redox mediation in nonaqueous Li-O2 batteries. ACS Catal. 7, 772–778 (2016).

Adams, B. D. et al. Towards a stable organic electrolyte for the lithium oxygen battery. Adv. Energy Mater. 5, 1400867 (2015).

Ganapathy, S. et al. Nature of Li2O2 oxidation in a Li–O2 battery revealed by operando X-ray diffraction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 16335–16344 (2014).

Ottakam Thotiyl, M. M., Freunberger, S. A., Peng, Z. & Bruce, P. G. The carbon electrode in nonaqueous Li–O2 cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 494–500 (2013).

Black, R., Lee, J.-H., Adams, B., Mims, C. A. & Nazar, L. F. The role of catalysts and peroxide oxidation in lithium–oxygen batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 392–396 (2013).

Wong, R. A. et al. Critically examining the role of nanocatalysts in Li–O2 batteries: viability toward suppression of recharge overpotential, rechargeability, and cyclability. ACS Energy Lett. 3, 592–597 (2018).

Lai, N.-C., Cong, G., Liang, Z. & Lu, Y.-C. A highly active oxygen evolution catalyst for lithium-oxygen batteries enabled by high-surface-energy facets. Joule 2, 1511–1521 (2018).

McCloskey, B. D. et al. On the efficacy of electrocatalysis in nonaqueous Li–O2 batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 18038–18041 (2011).

Radin, M. D., Monroe, C. W. & Siegel, D. J. How dopants can enhance charge transport in Li2O2. Chem. Mater. 27, 839–847 (2015).

Lu, Y.-C. et al. Lithium-oxygen batteries: bridging mechanistic understanding and battery performance. Energy Environ. Sci. 6, 750–768 (2013).

Ma, S. et al. Reversibility of noble metal-catalyzed aprotic Li-O2 batteries. Nano Lett. 15, 8084–8090 (2015).

Chen, Y., Freunberger, S. A., Peng, Z., Fontaine, O. & Bruce, P. G. Charging a Li–O2 battery using a redox mediator. Nat. Chem. 5, 489–494 (2013).

Chase, G. V. et al. Soluble oxygen evolving catalysts for rechargeable metal-air batteries. US Pat. 13/093, 759 (2011).

Sun, D. et al. A solution-phase bifunctional catalyst for lithium–oxygen batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 8941–8946 (2014).

Bergner, B. J., Schürmann, A., Peppler, K., Garsuch, A. & Janek, J. TEMPO: a mobile catalyst for rechargeable Li–O2 batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 15054–15064 (2014).

Lim, H.-D. et al. Rational design of redox mediators for advanced Li–O2 batteries. Nat. Energy 1, 16066 (2016).

Kundu, D., Black, R., Adams, B. & Nazar, L. F. A highly active low voltage redox mediator for enhanced rechargeability of lithium–oxygen batteries. ACS Cent. Sci. 1, 510–515 (2015).

Park, J.-B., Lee, S. H., Jung, H.-G., Aurbach, D. & Sun, Y.-K. Redox mediators for Li–O2 batteries: status and perspectives. Adv. Mat. 30, 1704162 (2018).

Chen, Y., Gao, X., Johnson, L. R. & Bruce, P. G. Kinetics of lithium peroxide oxidation by redox mediators and consequences for the lithium–oxygen cell. Nat. Commun. 9, 767 (2018).

Yu, W. et al. A soluble phenolic mediator contributing to enhanced discharge capacity and low charge overpotential for lithium-oxygen batteries. Electrochem. Commun. 79, 68–72 (2017).

Xu, C. et al. Bifunctional redox mediator supported by an anionic surfactant for long-cycle Li–O2 batteries. ACS Energy Lett. 2, 2659–2666 (2017).

Li, Y. et al. Li–O2 cell with LiI(3-hydroxypropionitrile)2 as a redox mediator: insight into the working mechanism of I– during charge in anhydrous systems. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 8, 4218–4225 (2017).

Bergner, B. J. et al. How to improve capacity and cycling stability for next generation Li–O2 batteries: approach with a solid electrolyte and elevated redox mediator concentrations. ACS Appl. Mater. Interf. 8, 7756–7765 (2016).

Kwak, W.-J., Jung, H.-G., Aurbach, D. & Sun, Y.-K. Optimized bicompartment two solution cells for effective and stable operation of Li–O2. Batter. Adv. Energy Mater. 7, 1701232 (2017).

Lee, D. J., Lee, H., Kim, Y.-J., Park, J.-K. & Kim, H.-T. Sustainable redox mediation for lithium–oxygen batteries by a composite protective layer on the lithium-metal anode. Adv. Mat. 28, 857–863 (2016).

Kim, B. G. et al. A moisture- and oxygen-impermeable separator for aprotic Li-O2 batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 26, 1747–1756 (2016).

Kwak, W.-J., Kim, H., Jung, H.-G., Aurbach, D. & Sun, Y.-K. Review—a comparative evaluation of redox mediators for Li-O2 batteries: a critical review. J. Electrochem. Soc. 165, A2274–A2293 (2018).

Bryantsev, V. S. & Faglioni, F. Predicting autoxidation stability of ether- and amide-based electrolyte solvents for Li–air batteries. J. Phys. Chem. A 116, 7128–7138 (2012).

Bryantsev, V. S. et al. Predicting solvent stability in aprotic electrolyte Li–air batteries: nucleophilic substitution by the superoxide anion radical (O2•–). J. Phys. Chem. A 115, 12399–12409 (2011).

Mahne, N., Fontaine, O., Thotiyl, M. O., Wilkening, M. & Freunberger, S. A. Mechanism and performance of lithium-oxygen batteries—a perspective. Chem. Sci. 8, 6716–6729 (2017).

Kwak, W.-J., Park, J.-B., Jung, H.-G. & Sun, Y.-K. Controversial topics on lithium superoxide in Li–O2 batteries. ACS Energy Lett. 2, 2756–2760 (2017).

Zhang, X. et al. LiO2: cryosynthesis and chemical/electrochemical reactivities. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 8, 2334–2338 (2017).

Kumar, N., Radin, M. D., Wood, B. C., Ogitsu, T. & Siegel, D. J. Surface-mediated solvent decomposition in Li–air batteries: impact of peroxide and superoxide surface terminations. J. Phys. Chem. C. 119, 9050–9060 (2015).

Black, R. et al. Screening for superoxide reactivity in Li-O2 batteries: effect on Li2O2/LiOH crystallization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 2902–2905 (2012).

Mahne, N., Renfrew, S. E., McCloskey, B. D. & Freunberger, S. A. Electrochemical oxidation of lithium carbonate generates singlet oxygen. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 5529–5533 (2018).

Schafzahl, L. et al. Singlet oxygen during cycling of the aprotic sodium–O2 battery. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 15728–15732 (2017).

Mahne, N. et al. Singlet oxygen generation as a major cause for parasitic reactions during cycling of aprotic lithium-oxygen batteries. Nat. Energy 2, 17036 (2017).

Wandt, J., Jakes, P., Granwehr, J., Gasteiger, H. A. & Eichel, R.-A. Singlet oxygen formation during the charging process of an aprotic lithium–oxygen battery. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 6892–6895 (2016).

Carboni, M., Marrani, A. G., Spezia, R. & Brutti, S. Degradation of LiTfO/TEGME and LiTfO/DME electrolytes in Li-O2 batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 165, A118–A125 (2018).

Borisov, S. M. et al. New NIR-emitting complexes of platinum(II) and palladium(II) with fluorinated benzoporphyrins. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 201, 128–135 (2009).

DeRosa, M. C. & Crutchley, R. J. Photosensitized singlet oxygen and its applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 233–234, 351–371 (2002).

Orfanopoulos, M., Smonou, I. & Foote, C. S. Intermediates in the ene reactions of singlet oxygen and N-phenyl-1,2,4-triazoline-3,5-dione with olefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 112, 3607–3614 (1990).

Singleton, D. A. et al. Mechanism of Ene reactions of singlet oxygen. A two-step no-intermediate mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 1319–1328 (2003).

Aubry, J.-M., Pierlot, C., Rigaudy, J. & Schmidt, R. Reversible binding of oxygen to aromatic compounds. Acc. Chem. Res. 36, 668–675 (2003).

Leach, A. G., Houk, K. N. & Foote, C. S. Theoretical prediction of a perepoxide intermediate for the reaction of singlet oxygen with trans-cyclooctene contrasts with the two-step no-intermediate Ene reaction for acyclic alkenes. J. Org. Chem. 73, 8511–8519 (2008).

Ogilby, P. R. Singlet oxygen: there is indeed something new under the sun. Chem. Soc. Rev. 39, 3181–3209 (2010).

Curran, H. J., Gaffuri, P., Pitz, W. J. & Westbrook, C. K. A comprehensive modeling study of n-heptane oxidation. Combust. Flame 114, 149–177 (1998).

Freunberger, S. A. et al. Reactions in the rechargeable lithium–O2 battery with alkyl carbonate electrolytes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 8040–8047 (2011).

Jensen, F., Greer, A. & Clennan, E. L. Reaction of organic sulfides with singlet oxygen. A revised mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120, 4439–4449 (1998).

Foote, C. S. & Peters, J. W. Chemistry of singlet oxygen. XIV. Reactive intermediate in sulfide photooxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 93, 3795–3796 (1971).

Gu, C.-L., Foote, C. S. & Kacher, M. L. Chemistry of singlet oxygen. 35. Nature of intermediates in the photooxygenation of sulfides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 103, 5949–5951 (1981).

Becke, A. D. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 5648–5652 (1993).

Tomasi, J., Mennucci, B. & Cammi, R. Quantum mechanical continuum solvation models. Chem. Rev. 105, 2999–3094 (2005).

Wilson, T., Golan, D. E., Harris, M. S. & Baumstark, A. L. Thermolysis of tetramethoxy- and p-dioxenedioxetanes. Kinetic parameters, chemiluminescence, and yields of excited products. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 98, 1086–1091 (1976).

Vacher, M. et al. Chemi- and bioluminescence of cyclic peroxides. Chem. Rev. 118, 6927–6974 (2018).

Lepage, D., Michot, C., Liang, G., Gauthier, M. & Schougaard, S. B. A soft chemistry approach to coating of LiFePO4 with a conducting polymer. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 6884–6887 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Human Resources Development program (No. 20184010201720) of a Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning (KETEP) grant, funded by the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy of the Korean government, and supported by National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government Ministry of Education and Science Technology (MEST) (NRF-2018R1A2B3008794). S.A.F. is indebted to the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement no. 636069) and the Austrian Federal Ministry of Science, Research and Economy and the Austrian Research Promotion Agency (grant No. 845364) and initial funding from the Austrian Science Fund (FWF, Project No. P26870-N19). The work by L.A.C. and P.C.R. was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, Vehicle Technologies Office.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.-J.K. conceived the concept and designed the experiments. W.-J.K., H.K., Y.K.P., C.L., T.T.N., N.M., H.-G.J. and S.M.B. performed the experiments. P.R. and L.A.C. performed the density functional theory calculations. S.A.F., W.-J.K., H.K., Y.K.P. and C.L. interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. Y.-K.S. led the co-work for this study. Y.-K.S. and S.A.F. supervised this work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Journal peer review information: Nature Communications thanks Pedro Arrechea and Zhangquan Peng for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kwak, WJ., Kim, H., Petit, Y.K. et al. Deactivation of redox mediators in lithium-oxygen batteries by singlet oxygen. Nat Commun 10, 1380 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09399-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09399-0

This article is cited by

-

Solving the Singlet Oxygen Puzzle in Metal-O2 Batteries: Current Progress and Future Directions

Electrochemical Energy Reviews (2024)

-

Li–air batteries: air stability of lithium metal anodes

Science China Chemistry (2024)

-

Roadmap for rechargeable batteries: present and beyond

Science China Chemistry (2024)

-

Metal sulfide heterojunction with tunable interfacial electronic structure as an efficient catalyst for lithium-oxygen batteries

Science China Materials (2023)

-

Threshold potentials for fast kinetics during mediated redox catalysis of insulators in Li–O2 and Li–S batteries

Nature Catalysis (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.