Abstract

Extracellular electron uptake (EEU) is the ability of microbes to take up electrons from solid-phase conductive substances such as metal oxides. EEU is performed by prevalent phototrophic bacterial genera, but the electron transfer pathways and the physiological electron sinks are poorly understood. Here we show that electrons enter the photosynthetic electron transport chain during EEU in the phototrophic bacterium Rhodopseudomonas palustris TIE-1. Cathodic electron flow is also correlated with a highly reducing intracellular redox environment. We show that reducing equivalents are used for carbon dioxide (CO2) fixation, which is the primary electron sink. Deletion of the genes encoding ruBisCO (the CO2-fixing enzyme of the Calvin-Benson-Bassham cycle) leads to a 90% reduction in EEU. This work shows that phototrophs can directly use solid-phase conductive substances for electron transfer, energy transduction, and CO2 fixation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Microbial phototrophic carbon dioxide (CO2) fixation accounts for substantial primary productivity on Earth1. Anoxygenic phototrophs, which include the green and purple sulfur bacteria, are metabolically versatile microbes that oxidize an array of inorganic compounds2. These include H2S, H2, Fe2+, and intriguingly, solid-phase conductive substances (SPCSs) via a process called extracellular electron uptake (EEU)3,4,5. Microbial oxidation–reduction reactions with SPCSs play an important role in soil, marine sediments, and deep subsurface microbial communities6. The cellular electron transfer and metabolic pathways that allow photoautotrophs to utilize SPSCs via EEU, however, are largely unknown. It remains elusive whether electron uptake from SPSCs is connected to cyclic photosynthetic electron transfer and/or the generation of reducing equivalents for CO2 fixation. Subsequently, the ecological and evolutionary role of phototrophic EEU remains poorly understood.

Poised electrodes in bioelectrochemical systems (BESs) have been used as proxies of microbial interactions with natural SPCSs, such as metal oxides5,7. Studies using BESs have led to fundamental insights into the molecular underpinnings of extracellular electron transfer in mineral respiring microbes4,8. These studies have revealed extracellular electron transfer is a widespread process in nature4,5,8. Furthermore, microbe-electrode interactions have been leveraged for biotechnological applications such as microbial electrosynthesis9. Our laboratory3,10, and others11,12, have recently applied BESs to better understand the molecular details of microbial phototrophic EEU. This has led to the discovery of at least two pure cultures capable of EEU from electrodes, the anoxygenic phototrophs Rhodopseudomonas palustris TIE-13 and Prosthecochloris aestuarii12. Thus far, only R. palustris TIE-1 is genetically tractable13, and as such is a model system for studying EEU.

Here, we use an interdisciplinary approach combining bioelectrochemistry, molecular biology, isotope-based geochemistry, nanotechnology, and microfluidics, to examine the bioenergetic pathways and physiological electron sinks that allow photoautotrophs to use SPCSs as electron donors. Using TIE-1 as a model system we show that EEU is linked to the photosynthetic electron transport chain (pETC), and that this process leads to cells becoming highly reduced with respect to both the intracellular nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide [NAD(H)] and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate [NAD(P)(H)] pools. We also test the ability of TIE-1 to fix CO2 during EEU using labeling studies. These data show that EEU results in CO2 fixation to biomass via the Calvin-Benson-Bassham (CBB) cycle. Furthermore, using mutant analysis we observe that the CBB cycle is the primary electron sink. Overall, our results trace the path of electrons following EEU through the electron transport chain and cellular metabolism.

Results

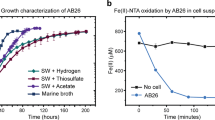

EEU is linked to photosynthetic electron transfer

EEU from metal oxides or poised electrodes into bacterial cells has been observed in pure cultures3,4,5,6,12,14,15,16,17,18,19,20, and mixed microbial communities4,5,21,22,23. However, the electron transfer pathways that underlie EEU have only been probed in chemotrophic microbes14,15,18,24. In phototrophic microbes, it is unknown if electrons from a cathode enter the pETC and if this activity is important for the establishment of a proton motive force (PMF), ATP synthesis, or the generation of reducing equivalents. Bioelectrochemical studies traditionally rely upon macroscale (>500 mL) or mesoscale (0.2–500 mL) BESs that are scaled for biomass production25. In such BESs it is difficult to isolate the response of surface-attached cells. This is because other factors like the influence of planktonic cells3,10, extracellular enzymes26, and abiotic reactions confound the interpretation of electrochemical data3,10. Being able to collect electrochemical data from surface-attached cells exclusively would shed light on whether EEU leads to electron transfer into the pETC.

To achieve this, we designed and constructed a microfluidic bioelectrochemical cell (µ-BEC) (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Figure 1). The µ-BEC is a four-chamber, three-electrode, small-volume (1.6 µL per well) BES that is compatible with confocal microscopy (Fig. 1a) (see Methods for a complete description of the µ-BEC design and assembly). Its major advantage is that it allows us to study surface-attached cells exclusively as planktonic cells can be washed out with microfluidic control (Fig. 1b). Appropriately grown microbial cells were incubated in µ-BECs for ~120 h at +100 mV vs. standard hydrogen electrode (SHE) under continuous illumination. Once we obtained stable current densities under illuminated conditions (~ −100 nA cm−2), planktonic cells were washed out of the system with microfluidic control. Medium flow was turned off following this wash because constant flow led to excessive noise in the electrochemical data. To determine that we only had surface-attached cells and no plankton, we performed confocal fluorescence microscopy with LIVE/DEAD® staining in the intact µ-BEC. We observed surface-attached cells in single-layer biofilms (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Figure 2a). Previous studies have shown that EEU-capable microbes, including TIE-1, make single-layer biofilms on electrodes3,9,27,28,29. Furthermore, we were unable to detect the presence of any motile planktonic cells in the µ-BEC.

Extracellular electron uptake in the micro-bioelectrochemical cell. a Schematic drawing of a single, four-chamber micro-bioelectrochemical (µ-BEC) with b microbial cells attached to the indium tin oxide (ITO) working electrode (WE). The reference (RE) and counter (CE) electrodes are silver and platinum wires, respectively (not drawn to scale). c Confocal micrograph of Rhodopseudomonas palustris TIE-1 biofilms attached to the WE under poised conditions using LIVE/DEAD® staining. Green cells are viable. Scale bars are 10 µm. d Current densities for TIE-1 wild-type (WT) (black) in the µ-BEC under illuminated and dark conditions (shaded regions) compared to a ‘No cell control’ reactor (red). Data shown are representative of three experiments. Source data are provided as a Source Data File

We used the above approach to obtain surface-attached cells in the µ-BEC and used these biofilms to study the influence of light and chemical inhibitors on EEU. Confocal imaging using LIVE/DEAD® staining was performed in the intact µ-BEC after these tests that typically lasted for a few minutes (see Methods for details). We observed light-stimulated EEU by pre-established wild-type (WT) TIE-1 biofilms (Fig. 1d). Upon illumination, biofilms reached stable current densities within ~1–2 s and typically reached a maximum of ~ −100 nA cm−2 (Supplementary Table 1,2,3). Overall, the µ-BEC replicates the biofilm architecture reported in bulkier systems and permits reproducible measurements of EEU by surface-attached cells.

To better understand electron flow during EEU we pursued a chemical probe-based approach to selectively inhibit key proteins involved in cyclic pETC. TIE-1 and related anoxygenic phototrophs use cyclic photosynthesis30 to generate energy (Fig. 2). The photosystem (P870) is reported to be at the potential of +450 mV30. Quinones reduced by the photosynthetic reaction center (P870*) donate electrons to the proton-translocating cytochrome bc131. Electrons are then transferred to cytochrome c2, and cycled back to the reaction center30. To test whether cytochrome bc1 is involved in EEU, we used antimycin A, a specific inhibitor of cytochrome bc132 to block cyclic pETC (Fig. 2a). Antimycin A is a quinone analog that blocks the Qi site of cytochrome bc1, inhibiting electron transfer from ubiquinol to cytochrome b, thus disrupting the proton motive Q cycle31,32. We observed a decrease in current uptake with antimycin A treatment (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Table 1). Current density became anodic (positive current) under phototrophic conditions (12.46 ± 1.34 nA cm−2; P < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA) relative to untreated controls (−85.5 ± 5.42 nA cm−2) but reverted to cathodic (negative current) densities under dark conditions (−3.46 ± 1.80 nA cm−2; P = 0.0006, one-way ANOVA) (Fig. 2a). Importantly, we did not observe a difference in the number of live/dead cells attached to electrodes in inhibitor treated vs. untreated control reactors (Supplementary Figure 2). These data suggest that electrons enter the pETC and that cytochrome bc1 is involved in electron flow during EEU.

Photosynthetic electron transfer is required for extracellular electron uptake. Current densities of TIE-1 wild-type (WT) in response to inhibition of the photosynthetic ETC under illuminated and dark (shaded regions) conditions with (a) antimycin A, (b) carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazine (CCCP), and (c) rotenone. Data shown are representative of three experiments. Each current density diagram (left) is followed by the proposed path of electron flow (right). The site of chemical inhibition is indicated by a red halo on the electron path diagrams. P870 (photosystem), P870* (excited photosystem), UQ (ubiquinone), bc1 (cytochrome bc1), c2 (cytochrome c2), NADH-DH (NADH dehydrogenase), Δp (proton gradient), H+ (protons), hv (light), ? (currently unknown), PMF (proton motive force) and ATP (adenosine triphosphate). Source data are provided as a Source Data File

Cyclic electron flow by the pETC is important for the establishment of a PMF that drives ATP production30. To investigate whether a proton gradient is important for EEU, we exposed TIE-1 biofilms to the protonophore carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP) (Fig. 2b). CCCP is a lipid-soluble molecule that dissipates the PMF such that electron transfer is uncoupled from ATP synthesis30,33. We observed a decrease in current uptake heading toward anodic current under illuminated conditions upon CCCP treatment (21.2 ± 9.13 nA cm−2; P < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA) compared to untreated controls (−113.5 ± 21.7 nA cm−2) (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Table 2). Current uptake was not different between CCCP (−18.4 ± 14.0 nA cm−2; P = 0.8666, one-way ANOVA) and untreated controls (−17.52 ± 3.41 nA cm−2) under dark conditions (Fig. 2b). These results demonstrate that a PMF is required for EEU. Furthermore, dark EEU is not PMF-dependent as EEU can occur in the presence of CCCP.

The proton-translocating NADH dehydrogenase oxidizes NADH to generate a PMF for ATP production30. NADH dehydrogenase can also function in reverse to catalyze uphill electron transport from the ubiquinone pool to reduce NAD+ in the anoxygenic phototrophs Rhodobacter capsulatus34 and R. sphaeroides35. Its activity is linked to redox homeostasis and carbon metabolism in these organisms36. To investigate whether NADH dehydrogenase has a role in EEU in TIE-1, we treated cells with the NADH dehydrogenase inhibitor rotenone37. Rotenone blocks electron transfer from the iron-sulfur clusters in NADH dehydrogenase to ubiquinone38 (Fig. 2c). In illuminated biofilms, we observed a ~20% decrease in current uptake with low rotenone concentrations (25 µM; −71.8 ± 2.02 nA cm−2; P < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA) compared to untreated controls (−94.7 ± 3.61 nA cm−2), and up to a ~50% decrease with exposure to high rotenone concentrations (100 µM; −41.6 ± 4.55 nA cm−2; P < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA) (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Table 3). The current uptake maxima were markedly lower under these conditions (Supplementary Table 3). After initial current uptake, we observed that rotenone-treated cells showed lowered current uptake post light exposure (Fig. 2c). It is unclear if this reduction is solely due to lowered current uptake or a combination of both lowered current uptake and increased electron donation to the electrode. The reduction in current uptake could also be a consequence of overreduction of the ubiquinone pool as has been observed in R. sphaeroides NADH dehydrogenase mutants38,39. Because we observe only a partial lowering of current uptake with NADH dehydrogenase inhibition (Fig. 2c), the cell likely has additional sinks for using reduced ubiquinone.

CCCP and antimycin A treatment both resulted in anodic current generation under illuminated conditions. Although the magnitude of the electrochemical response was different in the two cases, these data suggest that when the pETC is inhibited, TIE-1 cells likely transfer electrons to the poised electrodes by using them as an electron sink. Overall, our inhibitor studies show that (1) electrons enter the pETC of TIE-1 following EEU; (2) PMF is required for light-dependent EEU; (3) cytochrome bc1 is involved in electron flow; and that (4) NADH dehydrogenase plays an important role in EEU.

EEU leads to an imbalance in intracellular redox

NAD and its reduced state NADH are essential cofactors for microbes30. NADH can be converted to NAD(P)H via NAD(P)+ transhydrogenase40 (Rpal_4660-4662). NADH and NAD(P)H are key electron donors for biosynthetic reactions, including CO2 fixation. To better understand how the intracellular redox pool is affected by EEU, we examined the NADH/NAD+ and NAD(P)H/NAD(P)+ ratios in planktonic cells41. We compared these ratios to aerobic chemoheterotrophy (i.e., the inoculum) and phototrophic conditions where other electron donors were provided. We observed that the NADH/NAD+ ratio in the WT during EEU was higher than aerobic chemoheterotrophic growth (Fig. 3a). The NADH/NAD+ ratio was also higher than phototrophic growth on hydrogen (H2) or photoheterotrophic growth on acetate or butyrate (P < 0.0001; Fig. 3a, one-way ANOVA). The NAD(P)H/NAD(P)+ ratio was also highest during EEU compared to other conditions (P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA; Fig. 3b).

Extracellular electron uptake leads to a reducing intracellular redox environment. a TIE-1 WT NADH/NAD+ and b NAD(P)H/NAD(P)+ ratios under various growth conditions. Conditions tested: yeast-extract peptone (blue); photoheterotrophy with acetate (red) and butyrate (green); and photoautotrophy with H2 (yellow) or a poised electrode (black). Data are means ± s.e.m. of three biological replicates assayed in triplicate. The P values were determined by one-way ANOVA followed by a pairwise test with Bonferroni adjustment (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.0001; ns, not significant). c Transcriptomic analysis of the de novo NAD biosynthesis pathway under various photoautotrophic and photoheterotrophic growth conditions. d Genome-wide transcriptomic analysis of NAD(P)+/H-requiring reactions. Source data (and reactions not mentioned in text) are provided as a Source Data File

Analysis of intracellular redox suggests that EEU may lead to a highly-reduced environment in the cell. The lack of NAD+ or NAD(P)+ might require de novo NAD synthesis for cellular survival. Therefore, NAD biosynthesis might increase during EEU. We analyzed the expression of the de novo (aspartate-dependent) NAD biosynthesis pathway42 in the WT transcriptome encoded by nadABCDE. This pathway was not differentially expressed under any phototrophic condition, including EEU (Fig. 3c). NAD kinase which converts NAD+ to NAD(P)+ was also not differentially expressed under the conditions tested (Fig. 3c). These data suggest NAD biosynthesis does not increase at the level of gene expression during EEU despite a highly-reduced redox pool.

We reasoned that NAD(P)+ consuming and/or producing reactions might be upregulated during EEU to maintain redox balance. Therefore, we assessed the expression of NAD(P)+/H-requiring reactions across the TIE-1 genome. We observed that the majority of NAD(P)+/H-requiring reactions were downregulated under phototrophic conditions (Fig. 3d). Interestingly, an NADP-dependent FMN-binding flavin reductase-like protein (fre) was upregulated during photoautotrophic growth, increasing ~4-fold during EEU (Fig. 3d). A pair of NAD(P)+/H-dependent oxidoreductases (akr3 and akr4) were also differentially expressed (Fig. 3d). Akr3 was upregulated under all phototrophic conditions whereas akr4 was specifically upregulated during phototrophic H2 oxidation and EEU. These data suggest that under EEU the cells are highly reduced and that the lack of oxidized NAD+ and/or NAD(P)+ is not relieved by de novo NAD biosynthesis. However, several NAD(P)+/H-dependent reactions are upregulated.

EEU is linked to CO2 fixation via the CBB cycle

Our data shows that EEU results in electron transfer to the pETC (Fig. 2), eventually producing NADH and NAD(P)H (Fig. 3). In anoxygenic phototrophs CO2 fixation is a major sink for NAD(P)H30. In our initial study on EEU by TIE-1, we observed that mRNA transcripts for genes encoding form I ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RuBisCO) increased during EEU3. RuBisCO catalyzes CO2 fixation in many autotrophic organisms as part of the CBB cycle30. Therefore, we asked whether CO2 fixation occurs during EEU via RuBisCO. TIE-1 encodes two forms of RuBisCO: forms I (cbbLS) and II (cbbM)43. Using transcriptomic analysis, we analyzed the expression of the CBB cycle in TIE-1 and observed that form I ruBisCO was upregulated under all phototrophic conditions, but its expression was highest during EEU (~6-fold, P < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA) and phototrophic iron oxidation (~7-fold, P < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA) (Fig. 4a). Form II ruBisCO was expressed at similar levels across all phototrophic conditions (Fig. 4a). The other enzyme unique to the CBB cycle, phosphoribulokinase (Prk), was also upregulated during EEU (P < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA; Fig. 4a). Prk catalyzes the synthesis of the CO2 acceptor molecule, ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate (RuBP)30.

Extracellular electron uptake leads to carbon dioxide fixation. a Differential expression analysis of genes encoding Calvin-Benson-Bassham (CBB) cycle enzymes in TIE-1 wild-type (WT) under various photoautotrophic (poised electrodes, iron oxidation, and H2 oxidation) and photoheterotrophic growth conditions (acetate and butyrate). b 13CO2 incorporation under cathodic conditions in TIE-1 WT and the ruBisCO double mutant (∆form I ∆form II) biofilms and planktonic cells determined by secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS). Data are means ± s.e.m. of at least 25 cells. The P values were determined by one-way ANOVA followed by a pairwise test with Bonferroni adjustment (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.0001; ns, not significant). c Differential expression analysis of CO2 and HCO3− consuming reactions in TIE-1 WT. RuBP (Ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate), 1,3 BPG (1,3-bisphosphoglycerate), G3P (Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate), FBP (Fructose 1,6-bisphosphate), F6P (Fructose 6-phosphate), X5P (Xylulose 5-phosphate), Ru5P (Ribulose 5-phosphate) and R5P (Ribose 5-phosphate). Source data (and reactions not mentioned in text) are provided as a Source Data File

The expression of genes encoding CBB cycle-specific enzymes, including form I ruBisCO, suggests that CO2 fixation occurs during EEU. There are established methods for answering whether CO2 fixation is occurring in planktonic cells that can be grown in bulk44,45. However, in the case of EEU the cells attach to electrodes, which precludes us from using standard methodology. To overcome this, we employed secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS), and traced 13CO2 assimilation in TIE-1. The WT and a ruBisCO double mutant (∆cbbLS ∆cbbM) (Supplementary Table 4) were subjected to four treatments in BESs as follows: (1) poised electrodes with 12CO2; (2) poised electrodes with 12CO2 supplemented with 10% 13CO2 (poised + 13CO2); (3) electrodes at open circuit with 12CO2 (passing no current; control); and (4) electrodes at open circuit with 12CO2 supplemented with 10% 13CO2 (control + 13CO2) (Supplementary Figure 3). We chose to pre-grow cells under aerobic chemoheterotrophic conditions because the ruBisCO double mutant did not have a growth defect here compared to the WT (Supplementary Table 5). We used bulk BESs (~70 mL) here because they are closed systems, and do not lose CO2, unlike the μ-BEC, which is an anoxic microfluidic system under intermittent microfluidic flow.

Cells were cultivated for ~60 h, and planktonic and surface-attached cells (biofilms) were harvested for SIMS analysis. WT cells under poised conditions were enriched in 13C relative to the nonamended cells, indicating the assimilation of 13CO2 by both surface-attached and planktonic cells (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Table 6). The WT also increased in biomass above open circuit (Supplementary Figure 4). In contrast, the ruBisCO double mutant had a 96% reduction in 13CO2 assimilation compared to WT (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Table 7), a reduced capacity to take up electrons (Supplementary Figure 3) and no biomass increase (Supplementary Figure 4). These data demonstrate that EEU and CO2 assimilation are connected, and that RuBisCO catalyzes the major CO2 assimilation reaction in this system.

The planktonic and the surface-attached cells show the same level of 13C assimilation. This might be due to surface-attached cells and the plankton interacting dynamically with the electrode. To address this, we devised an experiment where pre-established biofilms (from 48 h bioreactor runs) on poised electrodes (biocathodes) were transferred into “plankton-free” bioreactors with fresh medium (Supplementary Figures 5). We observed that after 48 h current densities in “plankton-free” bioreactors were ~70% lower than the plankton-containing bioreactors (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA; Supplementary Figure 5a–e). Plankton increased to nearly 0.06 OD660, while the biocathode remained fully colonized (Supplementary Figure 5a–c, f). In a reciprocal experiment, when new cell-free cathodes were installed in the plankton-containing bioreactors (used to obtain the biocathodes), current densities resembled the original levels (Supplementary Figure 5a–e). This suggests that the plankton retains the ability to attach to the electrodes after 48 h. These data, along with 13CO2 assimilation, suggests that planktonic cells in the bioreactors are interacting dynamically with the poised electrodes.

The uptake of 13CO2 in the ruBisCO double mutant (Fig. 4b) likely represents CO2 consuming reactions such as non-autotrophic carboxylases shown in Fig. 4c. Multiple carboxylases in the TIE-1 genome are expressed during EEU, however, many of these reactions are downregulated relative to chemoheterotrophic growth (Fig. 4c). cynS, which encodes cyanase is upregulated during EEU (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA; Fig. 4c). Cyanase catalyzes the bicarbonate-dependent metabolism of cyanate, that accumulates as a byproduct of urea dissociation and/or carbamoyl phosphate decomposition46. Overall, our data suggest that RuBisCO is the primary reaction that is catalyzing CO2 fixation during EEU.

The CBB cycle is a primary electron sink for EEU

RuBisCO catalyzes a reaction between RuBP and CO2 that results in the formation of two molecules of 3-phosphoglycerate (3-PGA), with no requirement for reducing equivalents30. The reactions that follow, however, require ATP and NAD(P)H. Phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) catalyzes the phosphorylation of 3-PGA by ATP, which is converted in the reductive phase of the cycle by glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) into glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate (G3P). Thus, the CBB cycle, and not RuBisCO directly, is likely the electron sink for EEU. Because ruBisCO is the primary autotrophic carboxylase (Fig. 4b) and because form I ruBisCO was upregulated during EEU (Fig. 4a), we tested the effect of the lack of ruBisCO on this process.

We grew WT and the ruBisCO double mutant in bulk BESs. We chose this bioelectrochemical format because of the need for more biomass for downstream studies. After ~60 h of incubation in bulk BESs, the peak current density in the WT remained stable at ~ −1.5 µA cm−2 (Fig. 5a). The ruBisCO double mutant had a 90% reduction in current uptake vs. WT (P < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA; Fig. 5a). To assess ruBisCO gene expression, we performed reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) on the planktonic cells. In the WT, form I ruBisCO was upregulated ~8-fold with an associated downregulation of form II ruBisCO (P < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA; Fig. 5b). These expression data in the WT coincide with previous studies on EEU by TIE-13.

RuBisCO is required for extracellular electron uptake. a Endpoint current densities for ruBisCO deletion mutants compared to TIE-1 wild-type (WT). Data are means ± s.e.m. of three biological replicates. b ruBisCO mRNA log2 fold change under poised current (cathodic) and no current (open-circuit) conditions for TIE-1 WT and ruBisCO deletion mutants. c LIVE/DEAD® staining of electrode-attached cells under cathodic conditions. Data are means ± s.e.m. of three biological replicates assayed in triplicate. % represents the percent cells in relation to the total number of cells counted. d Endpoint current densities for ruBisCO complementation mutants. Data are means ± s.e.m. of three biological replicates. e ruBisCO mRNA log2 fold change under cathodic conditions for TIE-1 WT and ruBisCO complementation mutants. f LIVE/DEAD® staining of electrode-attached cells under cathodic conditions. Data are means ± s.e.m. of three biological replicates assayed in triplicate. g Endpoint current densities under standard conditions (WT) and when treated with gentamicin (WT + gentamicin). Data are means ± s.e.m. of three biological replicates. h Log10 colony forming units (CFU) and generation time (h) of planktonic cells incubated under standard conditions (WT) and when treated with gentamicin (WT + gentamicin). Data are means ± s.e.m. of at least two biological replicates assayed in triplicate. i mRNA log2 fold change of photosynthetic reaction center (pufL), pio operon (pioA), and ATP synthase homologs (atp1, atp2) in TIE-1 WT and the ruBisCO double mutant. RT-qPCR data are means ± s.e.m. of two biological replicates assayed in triplicate. The P values were determined by one-way ANOVA followed by a pairwise test with Bonferroni adjustment (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.0001; ns, not significant). Source data are provided as a Source Data File

The ruBisCO mutants did not have a cell viability defect across incubations compared to the WT (P = 0.3691, one-way ANOVA; Fig. 5c, Supplementary Figure 6). We also assessed NADH/NAD+ and NAD(P)H/NAD(P)+ ratios in the ruBisCO double mutant and observed that these cells were more reduced under EEU compared to aerobic chemoheterotrophic conditions (Supplementary Figure 7). However, because these cells show very low current uptake (Fig. 5a), these data are difficult to interpret. Additionally, we did not observe a difference in ATP levels in the WT and the ruBisCO double mutant planktonic cells during EEU (P = 0.2612, one-way ANOVA; Supplementary Figure 8).

Upon complementation of the ruBisCO double mutant with form I and/or form II ruBisCO (Supplementary Table 4), current uptake reached ~ −0.75 µA cm−2, similar to EEU by the WT (Fig. 5d). This was above current uptake levels by the ruBisCO double mutant (P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA; Fig. 5d). We observed that form I and form II ruBisCO were expressed at levels similar to the WT (Fig. 5e). Similar to the ruBisCO deletion mutants, the ruBisCO complementation mutants did not have a cell viability defect compared to the WT (P = 0.0572, one-way ANOVA; Fig. 5f, Supplementary Figure 6).

RuBisCO deletion does not affect EEU due to a growth defect

To determine whether the EEU defect in the ruBisCO double mutant was growth-dependent, we inoculated WT cells into bioreactors containing a sub-lethal concentration of gentamicin to inhibit protein synthesis (Supplementary Figure 9). We observed that gentamicin-treated WT cells accepted 80% more electrons during EEU compared to the ruBisCO double mutant (P < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA; Fig. 5g). To assess a potential growth defect in the ruBisCO double mutant, we harvested the electrodes at the end of the incubations and used 5 mm sections as inoculum for chemoheterotrophic growth. We did not observe a growth defect in the ruBisCO double mutant upon re-growth compared to the WT (P = 0.8232, one-way ANOVA; Fig. 5h). Planktonic colony forming units (CFUs) for the ruBisCO double mutant harvested at the end of incubations in the bulk bioreactors were not different from the WT (P = 0.0804, one-way ANOVA; Fig. 5h). These data suggest that the lower EEU activity of the ruBisCO double mutant is not due to a growth defect.

We performed gene expression analysis using a set of genes that have been reported to be involved in EEU from electrodes3. We first assessed the expression level of the photosynthetic reaction center large subunit (pufL). Gene expression analysis showed a ~5-fold upregulation of pufL in the ruBisCO double mutant, very similar to the WT expression (P = 0.0559, one-way ANOVA; Fig. 5i). Because previous mutant studies have shown that the pioABC system, a gene operon essential for phototrophic iron oxidation47, also has a role in electron uptake3, we performed expression analysis of pioA in the ruBisCO double mutant and the WT. We observed that the expression level of pioA in the ruBisCO double mutant was not different from the WT (P = 0.0759, one-way ANOVA; Fig. 5i).

We also assessed the expression of the systems responsible for energy transduction. The TIE-1 genome contains two F-type ATPases: Atp1 and an “alternate” Atp2. atp1 showed lower upregulation (~4-fold) than atp2 (~7-fold) in both the WT and the ruBisCO double mutant (Fig. 5i). The WT transcriptomic data corroborate the RT-qPCR data where atp1 is downregulated during phototrophic growth conditions, including EEU, whereas atp2 is specifically upregulated during EEU (Supplementary Tables 8, 9). These results suggest that the atp2 operon plays an important role in ATP synthesis during EEU. Overall, our data suggest that the WT and the ruBisCO double mutant do not show any differences in the level of gene expression for critical genes required for EEU, pETC, and energy generation. These data, in conjunction with the lack of 13CO2 assimilation (Fig. 4b), suggests the ruBisCO double mutant cells may be using cellular reserves to stay viable under the conditions tested.

The CBB cycle is important for phototrophic H2 oxidation

The inability of the ruBisCO double mutant to take up electrons from solid electrodes suggests that the CBB cycle is the primary electron sink during EEU. This finding underscores that CO2 fixation is tightly linked to EEU in these bacteria. In order to probe whether this coupling extends to other growth conditions, we examined the ability of the ruBisCO double mutant to oxidize H2 under phototrophic conditions. We observed ~80% lower H2 consumption in the ruBisCO double mutant compared to the WT (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA; Fig. 6a, Supplementary Table 10) with a concomitant reduction in CO2 consumption (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA; Fig. 6b, Supplementary Table 10). We also observed an increase in biomass in the WT compared to the ruBisCO double mutant during phototrophic H2 oxidation (P < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA; Supplementary Figures 10, 11). These data suggest that CO2 fixation is an important electron sink under photoautotrophic conditions, where electron donors, such as H2, are oxidized to provide cellular reducing power.

RuBisCO is important for phototrophic hydrogen (H2) oxidation. a Hydrogen (H2) oxidation and b carbon dioxide (CO2) consumption by the ruBisCO double mutant (∆form I ∆form II) as a percent of consumption by TIE-1 wild-type (WT). Data are means ± s.e.m. of two biological replicates assayed in triplicate. c mRNA log2 fold change of photosynthetic reaction center (pufL), NiFe hydrogenase (hupL), and ATP synthase homologs (atp1, atp2) in WT and the ruBisCO double mutant. RT-qPCR data are means ± s.e.m. of two biological replicates assayed in triplicate. The P values were determined by one-way ANOVA followed by a pairwise test with Bonferroni adjustment (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.0001; ns, not significant). Source data are provided as a Source Data File

The ruBisCO double mutant might oxidize less H2 because gene expression of the uptake hydrogenase48 is lower. We therefore assessed the expression of the large subunit of the uptake hydrogenase (hupL) in the ruBisCO double mutant and found that its expression was not altered compared to WT levels (P = 0.3222, one-way ANOVA; Fig. 6c). This suggests that the level of phototrophic H2 oxidation between the WT and the ruBisCO double mutant should be similar. However, our data show a clear reduction in H2 oxidation of ~80% in the mutant strain. We also assessed the expression of pufL in the ruBisCO double mutant and found no difference in expression vs. the WT (P = 0.0753, one-way ANOVA; Fig. 6c). In contrast, atp1 gene expression was higher in the WT (P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA) while atp2 gene expression was higher in the ruBisCO double mutant (P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA; Fig. 6c). Our data suggest that the lack of ruBisCO affects the ability of TIE-1 to accept electrons from other electron donors such as H2.

Discussion

Microbes have been known to exchange electrons with SPCSs for nearly a century7. Although we know the underlying electron transfer pathways and electron sinks employed by microbes that use SPCSs as electron acceptors, these are largely unknown for microbes that use SPCSs as electron donors4,8. To fill this knowledge gap, here we used an interdisciplinary approach to study the model EEU-capable microbe R. palustris TIE-1. Our data shows that EEU from poised electrodes is connected to pETC and CO2 fixation (Fig. 7). We observe that electrons enter the pETC, and eventually these electrons reduce NAD+ for CO2 fixation via the CBB cycle (Fig. 7). Furthermore, NADH dehydrogenase plays an important role in EEU (Fig. 2) most likely for generation of reducing equivalents for cellular metabolism.

Conceptual model of phototrophic extracellular electron uptake. Extracellular electron uptake is connected to the photosynthetic electron transport chain (pETC) and carbon dioxide (CO2) fixation in R. palustris TIE-1. The CBB cycle (Calvin-Benson-Bassham) uses RuBisCO and is the primary sink for electrons that enter the photosystem from poised electrodes. The electrons are used by the CBB cycle as NAD(P)H (reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate) that is exchanged with NADH (reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide) produced via reverse electron flow. For details please read the text. ATP (adenosine triphosphate), e− (electrons), P870 (photosystem), P870* (excited photosystem), UQ (ubiquinone), bc1 (cytochrome bc1), c2 (cytochrome c2), H+ (protons), hv (light), ? (currently unknown), OM (outer membrane), P (periplasm), CM (cytoplasmic membrane) and ICM (inner cytoplasmic membrane)

Our inhibitor studies (Fig. 2) and biochemical assays (Fig. 3) suggest that during EEU, electron flow leads to NAD+ and NAD(P)+ reduction. Because the reduction potential of the electrode in our experiments is lower than that required to reduce NAD+/NAD(P)+ directly, reverse electron transfer has to occur. The path of reverse electron transfer has been extensively studied in chemolithoautotrophs34,37,39,49. In these bacteria, electrons from soluble ferrous iron enter at cytochrome c2. These electrons can reduce oxygen to generate a PMF for ATP synthesis. The PMF can also be used to drive reverse electron flow from cytochrome bc1 to NADH dehydrogenase to reduce NAD+34,37,39,49. NADH dehydrogenase-mediated reverse electron flow has also been observed in R. capsulatus34. This pathway for electron transfer to NAD+ has also been proposed for other anoxygenic phototrophs50,51. Our data implies reverse electron flow is also occurring during EEU in TIE-1.

Interestingly, we observe that EEU is reversible in TIE-1 (Fig. 2a, b). Although artificially induced in our system (i.e., only in the presence of antimycin A or CCCP), the reversibility of extracellular electron transfer pathways is broadly observed in bacteria donating electrons to SPCSs14,27. For example, Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 uses an electron conduit called the Mtr system to transfer electrons to SPSCs14. Mtr can also function in reverse to facilitate EEU14. The PioAB system (a homolog of the MtrAB system) in TIE-147 plays a role in EEU from poised electrodes3. Anoxygenic photoheterotrophs are known to use CO2 as an electron sink to maintain redox balance when growing on highly-reduced substrates such as butyrate52. In nature, photoheterotrophs may use this reversibility of the EEU pathways and use SPCSs as electron sinks.

SIMS analysis demonstrates CO2 fixation is occurring during EEU primarily via RuBisCO (Fig. 4). We observed 13C assimilation was identical in surface-attached and planktonic cells within the bulk bioreactors. Furthermore, reactors with planktonic cells have higher current densities versus plankton-free reactors (Supplementary Figure 5) suggesting that they contribute to EEU via an unknown mechanism (Supplementary Figure 12). Previously published work from our laboratory, however, suggests no redox active molecule is detectable in the spent-medium3. Our laboratory has also shown that a cathode-driven Fe(II)/Fe(III) redox cycle at +100 mV vs. SHE10, is also unlikely.

The ruBisCO mutant is impaired in using electron donors such as poised electrodes (Fig. 5) and H2 for photosynthesis (Fig. 6). This implies that the cells ability to fix CO2 via ruBisCO is relayed to the electron transfer machinery that accepts electrons from these electron donors. During EEU we observe both increased ruBisCO expression (Fig. 4a) and an increased NAD(P)H/NAD(P)+ ratio (Fig. 3b). In R. palustris CGA009/10, which is closely related to TIE-1, form I ruBisCO is transcriptionally activated in response to elevated NAD(P)H and ATP levels via a regulatory system called CbbRRS53,54. These studies suggest that form I RuBisCO may be a sensor of cellular energy and redox balance53,54. In TIE-1, the regulatory CbbRRS system may also sense NAD(P)H levels and regulate form I ruBisCO expression. Together, this suggests that NAD(P)H is a metabolite that communicates redox status to the CBB cycle by controlling ruBisCO expression. This relationship between carbon metabolism and electron transfer may be conserved in other organisms, and thus be broadly relevant in many ecosystems.

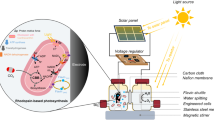

Our data highlights that photosynthetic EEU is linked to the CBB cycle for CO2 fixation. The link between EEU and the CBB cycle is the reducing equivalents produced via the pETC (Fig. 7). Because the CBB cycle1 and EEU4,5 are important processes in nature, primary productivity may be attributed to this process. Future studies will focus on quantitative measurements of the prevalence of autotrophic EEU such that EEU-linked CO2 fixation can be accounted for in global biogeochemical cycles. EEU from natural SPCSs such as rust might represent a strategy that autotrophic microbes use to access electrons for microbial survival when other electron donors are limiting or otherwise unavailable due to spatiotemporal constraints. Photoautotrophs, which are restricted to the photic zone, are known to exchange electrons with SPCSs, including magnetite55. Indeed, studies have shown that SPCSs can potentiate interspecies electron transfer55,56,57. For example, Geobacter sulfurreducens can exchange electrons with TIE-1 via mixed valent iron oxides55. Furthermore, long distance extracellular electron transfer has been observed by various researchers7,8. Although some microbes have evolved specialized membranes to facilitate long distance extracellular electron transfer58,59,60, microbes may also utilize electrically conductive minerals to access electrons in deeper sedimentary zones to overcome spatial separation from electron donors. Because SPCSs are ubiquitous8,61, EEU might be used both for microbial growth and survival.

Methods

Bacterial strains and culture conditions

All strains used in this study are indicated in Supplementary Table 4. The Rhodopseudmonas palustris TIE-1 ruBisCO deletion mutants (∆cbbLS, Rpal_1747-1748; ∆cbbM, Rpal_5122; and ∆cbbLS ∆cbbM) were constructed using a suicide plasmid system (Supplementary Table 4)13. A complete list of cloning and sequencing primers and restriction enzymes can be found in Supplementary Table 11. Escherichia coli strains were routinely cultivated in lysogeny broth (LB; pH 7.0) in 10 mL culture tubes or on LB agar at 37 °C. TIE-1 was pre-grown chemoheterotrophically at 30 °C in YP medium (0.3% yeast extract and 0.3% Bacto peptone) supplemented with 10 mM MOPS pH 7.0 (YPMOPS) in the dark. All growth experiments were carried out at 30 °C unless otherwise noted. All phototrophic growth experiments were carried out with a single 60 W incandescent light bulb at a distance of 25 cm. For anaerobic photoautotrophic growth TIE-1 strains were grown on 80% hydrogen-20% carbon dioxide (H2-CO2) at ~50 kPa in freshwater medium62 (FW) with 20 mM sodium bicarbonate in sterile, sealed, glass serum bottles. For anaerobic photoheterotrophic growth TIE-1 was grown in 10 mL FW medium supplemented with 1 mM acetate or butyrate from stock solutions (100 mM, pH = 7). In all cases where a change in culture medium was required cells were washed three times in basal FW medium post-centrifugation at 5000 × g. Bioelectrochemical reactor studies were performed with FW medium lacking exogenous electron donors, and purged with 80–20% nitrogen (N2-CO2). The complemention experiments were carried out with 1 mM IPTG and 800 µg mL−1 gentamicin for plasmid selection. Doubling time was calculated using the equation g = ln(2)/k, where k was determined from the slope of OD660 versus time on a log10 scale.

Complementation of ruBisCO knockouts

The TIE-1 form I ruBisCO (cbbLS) and form II ruBisCO (cbbM) genes were cloned such that the start site overlapped with an NdeI restriction site for cloning into pSRKGm (Supplementary Table 4). A complete list of primers and restriction enzymes used in cloning can be found in Supplementary Table 11. Post-cloning, the ruBisCO complementation plasmids were conjugated into the ruBisCO double mutant (∆cbbLS ∆cbbM) using the mating strain E. coli S17-1/λpir and selected on 800 µg mL−1 YPMOPS agar plates. A single colony was chosen and grown on 1 mM IPTG. Colonies were PCR screened using the primers in Supplementary Table 11. The pSRKGm empty vector was introduced into the WT and the ruBisCO double mutant to serve as controls (Supplementary Table 4).

RNA isolation and RT-qPCR

For bioelectrochemical studies, planktonic cells were sampled in an anaerobic chamber and immedietly mixed 1:1 with RNAlater® (Qiagen, USA). RNA was extracted using the RNeasy® Mini Kit according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (Qiagen, USA). DNA removal was performed using Turbo DNA-free™ Kit (Ambion, USA). RNA samples were tested for purity using PCR. Gene expression analysis of ruBisCO was performed using RT-qPCR with the comparative Ct method. Primer efficiencies were determined according to the manufacturers reccommendations. Purified RNA was used to synthesize cDNA with the iScript™ cDNA synthesis kit. clpX and recA were used as internal standards based on previous studies3. Primers for RT-qPCR outlined in Supplementary Table 12 were designed in Primer3 v4.1.0 (http://primer3.ut.ee) using the programs default parameters. The Bio-Rad iTaq™ Universal SYBR® Green Supermix and the Bio-Rad CFX Connect™ Real-Time System Optics ModuleA machine (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA) were used for all quantitative assays according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Differential expression (RNA-seq) analysis

Transcriptomic data sets were downloaded from NCBI (BioProject: PRJNA417278) and differential expression and statistical analysis was performed. Trimmomatic version 0.36 was used to trim Illumina sequencing reads (threshold = 20) and length filter (min = 60 bp)63. Processed reads were mapped to the published R. palustris TIE-1 genome using TopHat2 version 2.1.1 and the gff3 annotation file as a guide for sequence alignment64. Bowtie 2 version 2.3.3.1 was used to index the reference genome FASTA file65. The number of reads mapping to each feature were counted by HTSeq version 0.9.166. Differentially expressed genes were determined in DESEQ2 version 1.16.1 using the HTSeq read counts. To determine if genes were significantly differentially expressed an adjusted p-value cutoff of 0.05 was used. Heat maps were drawn in R using ggplot267.

Quantification of NADH/NAD+ and NAD(P)H/NAD(P)+ ratios

NADH/NAD+ and NAD(P)H/NAD(P)+ ratios were quantified using the “high-sensitivity” reagent mixture and sampling procedure41. Briefly, two separate 2 mL cell aliquots were sampled in an anaerobic chamber and centrifuged for 1 min at 21,000 × g to remove the supernatant. Cell pellets were then resuspended in 200 µL 0.2 M hydrochloric acid (for NAD+ and NAD(P)+) or sodium hydroxide (for NADH and NAD(P)H) for 10 min at 50 °C, then chilled on ice for 5 min. The reaction was then neutralized dropwise with equal volume 0.1 M acid or base and centrifuged for 5 min at 21,000 × g. The supernatant was stored at −80 °C for no more than one week. The enzyme cycling assays were performed on a BioTek Synergy™ HTX 96-well plate reader measuring absorbance at 570 nm41. A standard curve of known concentrations of NAD+ and NAD(P)+ was used to determine the concentration of samples.

ATP quantitation

ATP was extracted using the boiling water method68. Briefly, 2 mL of cells were centrigured at 21,000 × g for 1 min and the cell pellet was resuspended in 50 µL boiling sterile-filtered Milli-Q® water and allowed to sit at room temperature for 10 min. Samples were then centrifuged at 21,000 × g for 1 min and the supernatant was transferred to fresh microcentrifuge tubes and stored at −80 °C for no more than one week. The ATP Determination Kit (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was used to measure ATP concentrations using a standard curve of known concentrations according to the manufacturers reccomendations. Absorbance was measured at 560 nm. ATP concentrations were normalized to biomass (OD660).

Bulk BES setup and conditions

BESs were configured as previously described10. Briefly, FW media (70 mL) was dispensed into sterile, sealed, three-electrode BESs which were bubbled for 60 min with 80%:20% N2-CO2 to remove oxygen, and pressurized to ~50 kPa. The three electrodes were configured as follows: graphite working electrodes were ~3.2 cm2; reference eletrodes (Ag/AgCl) were submerged in 3 M KCl; and counter electrodes were composed of 5 cm2 platinum foil. Working electrodes were poised at +100 mV versus SHE using a multichannel potentionstat (Gamry Instruments, Warmister, PA) and operated continuously with a single 60 W incandescent light bulb at 26 °C. Data were collected every 1 min using the Gamry Echem Analyst™ (Gamry Instruments, Warmister, PA) software package. The biomass (OD660) of inoculated BESs was monitored with a BugLab Handheld OD Scanner (Applikon Biotechnology, Inc., Foster City, CA).

Quantification of live/dead bacteria on electrodes

Graphite electrodes were washed three times with anoxic 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove unattached cells in an anaerobic chamber. Sections of the electrode were cut with a sterile razor blade and immediately placed in sterile microfuge tubes containing anoxic 1× PBS. Prior to imaging, the electrode was immersed in LIVE/DEAD® stain (10 µM SYTO 9 and 60 µM propidium iodide, L7012, Life Technologies) and incubated for 15 min in the dark. Samples were then placed in 1× PBS in a glass bottom Petri dish (MatTek Corporation, Ashland, MA). For imaging biofilms in the intact µ-BEC, LIVE/DEAD® stain was flowed into the µ-BEC and allowed to incubate for 15 min in the dark. The excess stain was washed with sterile anoxic 1× PBS. Electrodes were imaged on a Nikon A1 inverted confocal microscope using 555 and 488 nm lasers and a ×100 objective (Washington University in St. Louis Biology Department Imaging Facility). Attached cells were quantified in Fiji v1.0 (https://fiji.sc) using the analysis pipeline described below. Briefly, images (n = 3) were inverted then converted to a 1-bit image by auto-thresholding. The “Watershed” tool was then applied to separate object edges. The “Analyze Particles” tool was used to generate cell counts for each image based on an area range (min = 16 pixels, max = 210 pixels) that was empirically determined from manually masking 100 cells. The red and green channels were split, and the “Analyze Particles” tool was used to count bacteria on each image (1024 × 1024 pixels).

Micro-bioelectrochemical cell (µ-BEC) setup and conditions

The µ-BECs were assembled from polymer fluidic layers, indium tin oxide (ITO) coverslips, and a glass layer with integrated reference and counter electrodes. Inlet, outlet, and connecting channels were laser cut into a 40 mm × 12.25 mm × 254-µm thick acetal polyoxymethylene (POM) adhesive tape. Four 4 mm diameter reaction chambers were cut into a second 127-µm thick acetal POM tape, aligned, and bonded to the channel layer using a pressure-sensitive acrylic adhesive. Prior to assembly, 1-mm diameter inlet/outlet holes were drilled into Borofloat® 33 1.75-mm thick glass capping layer (Schott AG, Mianz, Germany). Five hundred-micrometers of deep grooves were diced into the glass above the chamber midlines to locate 250-µm silver and platinum wires used for reference (RE) and counter (CE) electrodes, respectively (Xi'an Yima Opto-electrical Technology Co., Ltd, Shaanxi, China). Each 1.6 μL (0.125 cm2) well was enclosed by a 6 mm × 10 mm × 170-µm thick ITO-coated coverslip (30–60 Ω) (SPI supplies, West Chester, PA) to serve as the working electrode. Inlet and outlet tubes (Saint-Gobain TYGON® b-44-3; 1/16" ID × 1/8" OD) (United States Plastic Corp., Lima, OH) were attached on the glass capping layer and the 1/16" tube ends were capped with male/female luer lock fittings (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL). Microbial samples were injected into the µ-BEC using a FLOW EZ™ Fluigent Microflow Controller (Le Kremlin-Bicêtre, France) with 5 kPa 80–20% N2-CO2. Microbial cells were incubated in µ-BECs with working electrodes poised at +100 mV vs. SHE for ~120 h under illuminated conditions with a single 60 W incandescent light bulb at a distance of 25 cm to establish biofilms. Once we obtained stable current densities under illuminated conditions (~ −100 nA cm−2), planktonic cells were washed out of the system with microfluidic control and biofilms were immedietly treated with chemical inhibitors under dark conditions. Light “on-off” experiments were subsequently carried out at an interval of 10 s for a total of 200 s. Microfluidic flow was not applied during electrochemical data collection.

Analytical techniques

In order to quantify the amounts of H2 and CO2 consumption during photoautotrophic growth with H2, gas concentrations in headspace at the initial and final time points were measured. Twenty microliters of gas sample from the headspace was withdrawn using a HamiltonTM gas-tight syringe and analyzed using a Tracera GC-BID 2010 Plus, (Shimadzu Corp., Japan) equipped with an Rt®-Silica BOND PLOT Column (30 m × 0.32 mm; Restek, USA). Based on the measured partial pressures of H2 and CO2, their concentrations in headspace (moles of gas) were calculated using the ideal gas law (PV = nRT).

Secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS)

For planktonic assessments, 2 mL of cells were harvested from the bulk BESs and centrifuged at 4000 × g for 10 min. For biofilm assessments, cells were manually dislodged from the electrode by scraping with a sterile razor and resuspended in 950 µL of 1× PBS. Cells were then fixed with 50 µL of 20% paraformaldehyde fixative to a 1% final concentration and incubated at 4 °C for 24 h. After incubation, cells were pelleted by centrifugation, and washed with 1× PBS buffer twice to remove any residual fixative. Lastly, the cells were resuspended in 500 µL 100% ethanol and stored at −20 °C. Carbon isotopic compositions of individual cells were measured on a Cameca IMS 7f-GEO (Ametek Inc., USA) secondary ion mass spectrometer. Areas of interest (~100 µm2) were selected via scanning ion imaging, using the criterion of maximizing cell density, without compromising unambiguous individual cell identification. Scanning ion images of 12C14N− were used for this step, which was preceded by several minutes of pre-sputtering, in order to overcome the surface ion-yield transient region and achieve steady state secondary ion yield. Note that for biological specimens, nitrogen is monitored as CN− which provides a strong, unambiguous signal with which to locate the microbes69. Nominal primary ion settings were a 1.5-µm diameter, 20-keV net impact energy, 10 pA Cs+ beam rastered over a square area 100 microns per side. 12C− and 13C− scanning ion images were acquired, sequentially, using magnet switching and a single electron multiplier (EM) detector. In order to avoid EM saturation or aging, the instantaneous secondary ion count rate was restricted to <3 × 105 counts per second. A magnetic field settling time of 1 s was included prior to each new image acquisition. The acquisition time per image was nominally 5 s for 12C− and 55 s for 13C−. Image acquisition cycling continued until most cellular material was sputtered through (typically between 2 and 4 h). Between two and six fields of view were measured for each sample, depending on cell spacing. For these specimens, the most egregious isobaric interference was 12C1H−, which required a mass resolving power (MRP) of 2909 (M/dm) to achieve mass peak separation from 13C−. Therefore, the entrance and exit slits were set to achieve a flat-topped peak with MRP = 3000.

SIMS data analysis

Each region of interest (ROI; i.e., one individual cell) was selected using Cameca WinImage software (Ametek Inc., USA), and all count rates were exported for all ROIs for all cycles. EM dead time and quasi-simultaneous arrival corrections (QSA) were applied70. Note that these corrections made a relative change to the corrected ratio from the raw data ratio of only ~0.5% and ~0.2%, respectively. For each field of view, isotope ratios for all ROIs were plotted against cycle number. Based on numerous ‘blank’ analyses of unlabeled microbes, isotope ratios are not statistically ‘normally’ distributed around the mean value as the cell is sputtered through, being skewed at the onset of sputtering (despite pre-loading with Cs) and also when the cell is almost consumed. However, excluding these cycles, histograms of percent deviation from natural abundance of populations of ‘blank’ cells are, indeed, statistically normal, with a typical relative standard deviation < 1% (1 s, for >100 cells). (Note that a 1% relative standard deviation indicates, for example, that a 20% measured label isotope ratio increase would have a standard deviation of 0.2%). Once the cycles for each field of view were chosen, the ratios were averaged across those cycles for each region of interest. The data were then translated to deviations from unlabeled. For each test, a reference ratio, that is, the mean R13C (i.e., 13C/12C) of the unlabeled data set, is calculated. Then all ratios in that test were recalculated as ‰ (permil, or part per thousand) deviations from the unlabeled mean using the equation δ13Ctest = (R13Ctest/R13Cref−1)*1000 with Microsoft® Excel.

Electron transport chain inhibitors

Stock solutions (100×) of rotenone, antimycin A, and carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazine (CCCP) (MilliporeSigma, USA) were solubilized in 100% DMSO and stored as aliquots at −20 °C for no more than one day before use. For µ-BEC experiments, the stock solutions were suspended in 1× PBS before use.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses (Student’s t-test, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni adjustment) were performed with Microsoft® Excel “Data Analysis” tools.

Reporting summary

Further information on experimental design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data in this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request. The source data underlying Figs. 1d, 2a–b, 3a–d, 4a–c, 5a–i, 6a–c; Supplementary Figs. 2a–d, 3, 4, 5d–e, 6a-i, 7a–b, 8–11; and Supplementary Tables 1–3 and 5–7 and 10 are provided as a Source Data file. Sequencing reads used for differential expression analysis are available under BioProject PRJNA417278.

References

Kirchman, D. L. in Processes in Microbial Ecology 55–78 (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2018).

Imhoff J. F. Anoxygenic Photosynthetic Bacteria (Blankenship, R. E., Madigan, M. T. & Bauer, C. E. eds) 1–15 (Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1995).

Bose, A., Gardel, E. J., Vidoudez, C., Parra, E. A. & Girguis, P. R. Electron uptake by iron-oxidizing phototrophic bacteria. Nat. Commun. 5, 3391 (2014).

Tremblay, P. L., Angenent, L. T. & Zhang, T. Extracellular electron uptake: among autotrophs and mediated by surfaces. Trends Biotechnol. 35, 1–12 (2016).

Rosenbaum, M., Aulenta, F., Villano, M. & Angenent, L. T. Cathodes as electron donors for microbial metabolism: which extracellular electron transfer mechanisms are involved? Bioresour. Technol. 102, 324–333 (2011).

Rabaey, K. et al. Microbial ecology meets electrochemistry: electricity-driven and driving communities. ISME J. 1, 9–18 (2007).

Lovley, D. R. Extracellular electron transfer: wires, capacitors, iron lungs, and more. Geobiology 6, 225–231 (2008).

Shi, L. et al. Extracellular electron transfer mechanisms between microorganisms and minerals. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 14, 651–662 (2016).

Nevin, K. P. et al. Electrosynthesis of organic compounds from carbon dioxide catalyzed by a diversity of acetogenic microorganisms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 2882–2886 (2011).

Rengasamy, K., Ranaivoarisoa, T., Singh, R. & Bose, A. An insoluble iron complex coated cathode enhances direct electron uptake by Rhodopseudomonas palustris TIE-1. Bioelectrochemistry 122, 164–173 (2018).

Doud, D. F. & Angenent, L. T. Toward electrosynthesis with uncoupled extracellular electron uptake and metabolic growth: enhancing current uptake with Rhodopseudomonas palustris. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 1, 351–355 (2014).

Ha, P. T. et al. Syntrophic anaerobic photosynthesis via direct interspecies electron transfer. Nat. Commun. 8, 13924 (2017).

Jiao, Y., Kappler, A., Croal, L. R. & Newman, D. K. Isolation and characterization of a genetically tractable photoautotrophic Fe(II)-oxidizing bacterium, Rhodopseudomonas palustris strain TIE-1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 4487–4496 (2005).

Ross, D. E., Flynn, J. M., Baron, D. B., Gralnick, J. A. & Bond, D. R. Towards electrosynthesis in Shewanella: energetics of reversing the Mtr pathway for reductive metabolism. PLoS ONE 6, e16649 (2011).

Ishii, T., Kawaichi, S., Nakagawa, H., Hashimoto, K. & Nakamura, R. From chemolithoautotrophs to electrolithoautotrophs: CO2 fixation by Fe(II)-oxidizing bacteria coupled with direct uptake of electrons from solid electron sources. Front. Microbiol. 6, 994 (2015).

Summers, Z. M., Gralnick, J. A. & Bond, D. R. Cultivation of an obligate Fe(II)-oxidizing lithoautotrophic bacterium using electrodes. MBio 4, e00420–00412 (2013).

Lohner, S. T., Deutzmann, J. S., Logan, B. E., Leigh, J. & Spormann, A. M. Hydrogenase-independent uptake and metabolism of electrons by the archaeon Methanococcus maripaludis. ISME J. 8, 1673–1681 (2014).

Strycharz, S. M. et al. Gene expression and deletion analysis of mechanisms for electron transfer from electrodes to Geobacter sulfurreducens. Bioelectrochemistry 80, 142–150 (2011).

Nevin, K. P. et al. Electrosynthesis of organic compounds from carbon dioxide catalyzed by a diversity of acetogenic microorganisms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 2882–2886 (2011).

Beese-Vasbender, P. F., Nayak, S., Erbe, A., Stratmann, M. & Mayrhofer, K. J. Electrochemical characterization of direct electron uptake in electrical microbially influenced corrosion of iron by the lithoautotrophic SRB Desulfopila corrodens strain IS4. Electrochim. Acta 167, 321–329 (2015).

Rowe, A. R., Chellamuthu, P., Lam, B., Okamoto, A. & Nealson, K. H. Marine sediments microbes capable of electrode oxidation as a surrogate for lithotrophic insoluble substrate metabolism. Front. Microbiol 5, 784 (2014).

Wang, Z. et al. A previously uncharacterized, nonphotosynthetic member of the Chromatiaceae is the primary CO2-fixing constituent in a self-regenerating biocathode. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81, 699–712 (2015).

Lam, B. R., Rowe, A. R. & Nealson, K. H. Variation in electrode redox potential selects for different microorganisms under cathodic current flow from electrodes in marine sediments. Environ. Microbiol. 20, 2270–2287 (2018).

Rowe, A. R. et al. Tracking electron uptake from a cathode into Shewanella cells: implications for energy acquisition from solid-substrate electron donors. MBio 9, e02203–e02217 (2018).

Ren, H., Lee, H. S. & Chae, J. Miniaturizing microbial fuel cells for potential portable power sources: promises and challenges. Microfluid. Nanofluidics 13, 353–381 (2012).

Deutzmann, J. S., Sahin, M. & Spormann, A. M. Extracellular enzymes facilitate electron uptake in biocorrosion and bioelectrosynthesis. MBio 6, e00496–00415 (2015).

Gregory, K. B., Bond, D. R. & Lovley, D. R. Graphite electrodes as electron donors for anaerobic respiration. Environ. Microbiol. 6, 596–604 (2004).

Strycharz, S. M. et al. Graphite electrode as a sole electron donor for reductive dechlorination of tetrachlorethene by Geobacter lovleyi. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 5943–5947 (2008).

Strycharz, S. M. et al. Reductive dechlorination of 2‐chlorophenol by Anaeromyxobacter dehalogenans with an electrode serving as the electron donor. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2, 289–294 (2010).

White, D. in The Physiology and Biochemistry of Prokaryotes 112–117 (Oxford Press, Oxford, 2007).

Trumpower, B. L. Cytochrome bc 1 complexes of microorganisms. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 54, 101–129 (1990).

Knaff, D. B. The cytochrome bc 1 complexes of photosynthetic purple bacteria. Photosynth. Res. 35, 117–133 (1993).

Heytler, P. Uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation by carbonyl cyanide phenylhydrazones. I. Some characteristics of m-CI-CCP action on mitochondria and chloroplasts. Biochemistry 2, 357–361 (1963).

Herter, S. M., Kortlüke, C. M. & Drews, G. Complex I of Rhodobacter capsulatus and its role in reverted electron transport. Arch. Microbiol. 169, 98–105 (1998).

Spero, M. A. et al. Different functions of phylogenetically distinct bacterial complex I isozymes. J. Bacteriol. 198, 1268–1280 (2016).

Tichi, M. A., Meijer, W. G. & Tabita, F. R. Complex I and its involvement in redox homeostasis and carbon and nitrogen metabolism in Rhodobacter capsulatus. J. Bacteriol. 183, 7285–7294 (2001).

Dupuis, A. et al. Distal genes of the nuo operon of Rhodobacter capsulatus equivalent to the mitochondrial ND subunits are all essential for the biogenesis of the respiratory NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase. Mol. Microbiol. 28, 531–541 (1998).

Palmer, G., Horgan, D. J., Tisdale, H., Singer, T. P. & Beinert, H. Studies on the respiratory chain-linked reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide dehydrogenase XIV. Location of the sites of inhibition of rotenone, barbiturates, and piericidin by means of electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy. J. Biol. Chem. 243, 844–847 (1968).

Dupuis, A. Genetic disruption of the respiratory NADH-ubiquinone reductase of Rhodobacter capsulatus leads to an unexpected photosynthesis-negative phenotype. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 148, 107–113 (1997).

Jackson, J. The proton-translocating nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide transhydrogenase. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 23, 715–741 (1991).

Kern, S. E., Price-Whelan, A. & Newman, D. K. Extraction and measurement of NAD(P)(+) and NAD(P)H. Methods Mol. Biol. 1149, 311–323 (2014).

Begley, T. P., Kinsland, C., Mehl, R. A., Osterman, A. & Dorrestein, P. The biosynthesis of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotides in bacteria. Vitam. Horm. 61, 103–119 (2001).

Tabita, F. R., Satagopan, S., Hanson, T. E., Kreel, N. E. & Scott, S. S. Distinct form I, II, III, and IV Rubisco proteins from the three kingdoms of life provide clues about Rubisco evolution and structure/function relationships. J. Exp. Bot. 59, 1515–1524 (2008).

Sirevåg, R., Buchanan, B., Berry, J. & Troughton, J. Mechanisms of CO2 fixation in bacterial photosynthesis studied by the carbon isotope fractionation technique. Arch. Microbiol. 112, 35–38 (1977).

Shiba, H., Kawasumi, T., Igarashi, Y., Kodama, T. & Minoda, Y. The CO2 assimilation via the reductive tricarboxylic acid cycle in an obligately autotrophic, aerobic hydrogen-oxidizing bacterium, Hydrogenobacter thermophilus. Arch. Microbiol. 141, 198–203 (1985).

Ebbs, S. Biological degradation of cyanide compounds. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 15, 231–236 (2004).

Jiao, Y. & Newman, D. K. The pio operon is essential for phototrophic Fe(II) oxidation in Rhodopseudomonas palustris TIE-1. J. Bacteriol. 189, 1765–1773 (2007).

Rey, F. E., Oda, Y. & Harwood, C. S. Regulation of uptake hydrogenase and effects of hydrogen utilization on gene expression in Rhodopseudomonas palustris. J. Bacteriol. 188, 6143–6152 (2006).

Marrs, B., Stahl, C. L., Lien, S. & Gest, H. Biochemical physiology of a respiration-deficient mutant of the photosynthetic bacterium Rhodopseudomonas capsulata. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 69, 916–920 (1972).

Bird, L. J., Bonnefoy, V. & Newman, D. K. Bioenergetic challenges of microbial iron metabolisms. Trends Microbiol. 19, 330–340 (2011).

Bird, L. J. Interactions of Fe(II) with the iron oxidizing bacterium Rhodopseudomonas palustris TIE-1. Diss. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1–172 (2013).

McKinlay, J. B. & Harwood, C. S. Carbon dioxide fixation as a central redox cofactor recycling mechanism in bacteria. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 11669–11675 (2010).

Romagnoli, S. & Tabita, F. R. A novel three-protein two-component system provides a regulatory twist on an established circuit to modulate expression of the cbbI region of Rhodopseudomonas palustris CGA010. J. Bacteriol. 188, 2780–2791 (2006).

Joshi, G. S., Bobst, C. E. & Tabita, F. R. Unravelling the regulatory twist–regulation of CO2 fixation in Rhodopseudomonas palustris CGA010 mediated by atypical response regulator(s). Mol. Microbiol 80, 756–771 (2011).

Byrne, J. M. et al. Redox cycling of Fe(II) and Fe(III) in magnetite by Fe-metabolizing bacteria. Science 347, 1473–1476 (2015).

Kato, S., Hashimoto, K. & Watanabe, K. Microbial interspecies electron transfer via electric currents through conductive minerals. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 10042–10046 (2012).

Shrestha, P. M. & Rotaru, A. E. Plugging in or going wireless: strategies for interspecies electron transfer. Front. Microbiol 5, 237 (2014).

Reguera, G. et al. Extracellular electron transfer via microbial nanowires. Nature 435, 1098 (2005).

El-Naggar, M. Y. et al. Electrical transport along bacterial nanowires from Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 18127–18131 (2010).

Pfeffer, C. et al. Filamentous bacteria transport electrons over centimetre distances. Nature 491, 218 (2012).

Hernandez, M. & Newman, D. Extracellular electron transfer. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 58, 1562–1571 (2001).

Ehrenreich, A. & Widdel, F. Anaerobic oxidation of ferrous iron by purple bacteria, a new type of phototrophic metabolism. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60, 4517–4526 (1994).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014).

Kim, D. et al. TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol. 14, R36 (2013).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357 (2012).

Anders, S., Pyl, P. T. & Huber, W. HTSeq—a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 31, 166–169 (2015).

Wickman, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (Springer, Berlin, Germany, 2016).

Yang, N. C., Ho, W. M., Chen, Y. H. & Hu, M. L. A convenient one-step extraction of cellular ATP using boiling water for the luciferin-luciferase assay of ATP. Anal. Biochem. 306, 323–327 (2002).

Hoppe, P., Cohen, S. & Meibom, A. NanoSIMS: technical aspects and applications in cosmochemistry and biological geochemistry. Geostand. Geoanalytical Res. 37, 111–154 (2013).

Jones, C., Fike, D. A. & Peres, P. Investigation of the quasi-simultaneous arrival (QSA) effect on a CAMECA IMS 7f-GEO. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 31, 623–630 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We thank the following members of the Washington University community: Marta Wegorzewska for her careful reading of the manuscript; Dianne Duncan for her help with confocal microscopy; and Himadri Pakrasi, Robert Blankenship, Gautam Dantas, Joshua Blodgett, Wei Bai, Dinesh Gupta, and Yunci Qi for their helpful comments during the preparation of this manuscript. M.S.G. was supported by the Initiative for Maximizing Student Development (IMSD) training grant from the U.S. National Institutes of Health (grant number R25-GM103757). This work was supported by the following grants to A.B.: The David and Lucile Packard Foundation Fellowship (201563111), the U.S. Department of Energy (grant number DESC0014613; also to D.A.F.), and the U.S. Department of Defense, Army Research Office (grant number W911NF-18-1-0037). A.B. was also funded by a Collaboration Initiation Grant, an Office of the Vice Chancellor of Research Grant, and an International Center for Energy, Environment and Sustainability Grant from Washington University in St. Louis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.S.G, A.B., K.R., D.F., and J.M.M. designed the research. M.S.G, K.R., T.O.R, M.M.B., C.J., and R.S. collected the data. M.S.G, K.R., C.J., T.O.R., and A.B. analyzed and interpreted the data. M.S.G and A.B. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed, revised, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Journal peer review information: Nature Communications thanks Rodney Burton and Gemma Reguera for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source Data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guzman, M.S., Rengasamy, K., Binkley, M.M. et al. Phototrophic extracellular electron uptake is linked to carbon dioxide fixation in the bacterium Rhodopseudomonas palustris. Nat Commun 10, 1355 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09377-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09377-6

This article is cited by

-

Characterization and environmental applications of soil biofilms: a review

Environmental Chemistry Letters (2024)

-

Light-independent anaerobic microbial oxidation of manganese driven by an electrosyntrophic coculture

The ISME Journal (2023)

-

Engineering artificial photosynthesis based on rhodopsin for CO2 fixation

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Redox signaling-driven modulation of microbial biosynthesis and biocatalysis

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Moving towards the enhancement of extracellular electron transfer in electrogens

World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.