Abstract

Brassica napus (2n = 4x = 38, AACC) is an important allopolyploid crop derived from interspecific crosses between Brassica rapa (2n = 2x = 20, AA) and Brassica oleracea (2n = 2x = 18, CC). However, no truly wild B. napus populations are known; its origin and improvement processes remain unclear. Here, we resequence 588 B. napus accessions. We uncover that the A subgenome may evolve from the ancestor of European turnip and the C subgenome may evolve from the common ancestor of kohlrabi, cauliflower, broccoli, and Chinese kale. Additionally, winter oilseed may be the original form of B. napus. Subgenome-specific selection of defense-response genes has contributed to environmental adaptation after formation of the species, whereas asymmetrical subgenomic selection has led to ecotype change. By integrating genome-wide association studies, selection signals, and transcriptome analyses, we identify genes associated with improved stress tolerance, oil content, seed quality, and ecotype improvement. They are candidates for further functional characterization and genetic improvement of B. napus.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Brassica napus is an important oilseed crop, worldwide, and includes both tuberous (swede or rutabaga) and leafy (fodder rape and kale) forms used for animal fodder and human consumption1. During B. napus breeding, the undesirable oil components, erucic acid and aliphatic glucosinolate, in the seeds have undergone a dramatic reduction, whereas oil content, seed yield, and disease resistance have been significantly improved2. As described by the Triangle of U3, three allopolyploid species, Brassica napus (AACC, 2n = 38), Brassica juncea (AABB, 2n = 36), and Brassica carinata (BBCC, 2n = 34) each originated from hybridization between two of three ancestral diploid species, Brassica rapa (AA, 2n = 20), Brassica oleracea (CC, 2n = 18), and Brassica nigra (BB, 2n = 16). The three Brassica diploid progenitors are themselves ancient polyploids that experienced a lineage-specific whole-genome triplication, making the allopolyploid descendant B. napus an excellent model for investigating processes of polyploid speciation, evolution, and selection.

As one of the earliest allopolyploid crops, B. napus was formed by hybridization of B. rapa and B. oleracea1. The estimated formation time of B. napus were ~67004 and ~7500 years ago5 and 38,000−51,000 years ago6, based on two synonymous substitution (Ks) estimations and a Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) simulation, respectively. The literatures recorded that winter B. napus was first cultivated in Europe7. Around the year 1700, spring B. napus was developed and spread to England in the late 18th century8. The semi-winter ecotype was mainly cultivated in China, which was introduced from Europe in the 1930–1940s9. However, no truly wild B. napus populations are known7, leading to the precise identities of the two progenitors that hybridized to form B. napus remain elusive, as B. rapa and B. oleracea have morphologically diverse subspecies and have commonly been cultivated throughout Europe for hundreds of years. The natural hybridization among these species occurred occasionally under appropriate conditions. Although a recent study suggested that the B. napus A subgenome might be derived from the ancestor of European turnip (B. rapa ssp. rapa)6, more evidence to support the conclusion need to be provided, due to only 5 B. napus and 27 B. rapa accessions were included in their analysis. Previous studies based on nuclear and chloroplast markers also suggested that B. napus may have developed from an interspecific cross between turnip and broccoli, or resulted from several independent hybridization events10,11. To further understand the evolution of B. napus, it is necessary to reveal whether wild species or domesticated donors were parental progenitors, which B. rapa and B. oleracea subspecies involved in the formation of B. napus.

Genome resequencing has been used to identify genes that have contributed to domestication and improvement in crop plants, such as rice (Oryza sativa)12, tomato (Solanum lycopersicum)13, and soybean (Glycine max)14. Reference genomes of the three Brassica progenitors and the allopolyploid species B. napus and B. juncea have been released4,5,6,15,16,17. Resequencing of 199 B. rapa and 119 B. oleracea accessions18 will facilitate investigations of selection acting in each B. napus subgenome and will clarify the progenitors of the species.

Here, we perform genome sequencing of 588 B. napus accessions and transcriptome sequencing of 11 tissues from two B. napus accessions having different seed quality. The large number of variations identified not only provide insight into the origin and evolutionary history of B. napus, identifying genetic loci involved in its improvement, but also lay a foundation for further functional validation of candidate genes controlling important traits. Furthermore, the findings of this study provide a basis to facilitate breeding of B. napus and related crops with favorable traits.

Results

Sequencing and variation discovery

We resequenced 588 diverse B. napus accessions from 21 countries (Fig. 1a; Supplementary Tables 1; Supplementary Data 1) and obtained 4.03 Tb of clean data. After filtering, we aligned reads to the B. napus reference genome5. The mapping rate varied from 79.84 to 99.45%, and the effective mapped read depth averaged ~5× and ranged from 3.37× to 7.71×. We generated 5,294,158 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs; denoted as Bna) and 1,307,151 indels (Supplementary Data 2 and 3). Validation of 103 randomly selected SNPs in 20 accessions by Sanger sequencing indicated that most of the identified SNPs (95.1%) were authentic (Supplementary Data 4). The reliability of SNPs was further confirmed in that most SNPs (93.5 to 96.4%) were repeated in biological replicates of 20 accessions.

Geographic distribution and population structure of B. napus accessions. a Geographic distribution of 588 B. napus accessions in the world. b ML tree of all B. napus accessions inferred from SNPs at fourfold-degenerate sites. Phylogenetic tree was constructed using IQ-TREE19 with the best model GTR + F + ASC + R5. Clades with bootstrap values of above 50% are indicated by a circled blue dot. c PCA plot of all the B. napus accessions used in this study. a was generated in R (V3.2.5) using package rworldmap. Source data are provided as a Source Data file

We aligned the B. napus data to a B. napus ancestral pseudo-genome (merging the B. rapa and B. oleracea reference genomes; Supplementary Fig. 1) and divided the SNPs into BnaA and BnaC two sets, based on the two progenitors. B. rapa and B. oleracea sequencing data were mapped onto the corresponding reference genomes. Then, the SNPs called from B. rapa were combined with BnaA to form the A (B. rapa and B. napus) subgenome SNP set (denoted as BraA, including 529,771 SNPs). Similarly, the C (B. oleracea and B. napus) subgenome SNP set (denoted as BolC), including 675,457 SNPs, was obtained (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Origin of B. napus

Based on the optimal models (GTR + F + ASC + R5, GTR + F + ASC + R7, and TVM + F + ASC + R8 for the Bna, BraA, and BolC SNP sets, respectively) (Supplementary Data 5–7), we constructed maximum likelihood (ML) trees, using IQ-TREE19 (Figs 1a, 2a and 3a), resulting in divergent clades of B. napus and B. rapa or B. oleracea, respectively. Most B. napus accessions clustered together, based on ecotype, whereas clustering of B. rapa and B. oleracea largely reflected subspecies relationships. From the BraA phylogenetic tree, the B. napus clade was closest to the European turnip and distant from B. rapa ssp. rapa (Asian turnip) and other subspecies (Fig. 2a), consistent with a recent study suggesting that the B. napus A subgenome evolved from the ancestor of European turnip6.

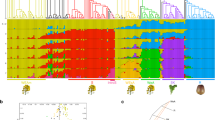

Population structure of 588 B. napus accessions and 199 of B. rapa accessions. a ML tree of all B. napus accessions and 199 B. rapa accessions inferred from SNPs at fourfold-degenerate sites. Phylogenetic tree was constructed using IQ-TREE with the best model GTR + F + ASC + R7. Clades with bootstrap values of above 50% are indicated by a circled blue dot. b PCA plot of 50 B. napus landraces and 199 B. rapa accessions. c Model-based Bayesian clustering of 50 B. napus landraces and 199 B. rapa accessions performed using STRUCTURE 2.1 with the number of ancestry kinships (K) set to 2, 3, or 4. Each accession is denoted by a vertical bar composed of different colors in proportions corresponding to its proportion of genetic ancestry from each of these ancestral populations. Source data are provided as a Source Data file

Population structure of 588 B. napus accessions and 119 of B. oleracea accessions. a ML tree of all B. napus accessions and 119 B. oleracea accessions inferred from SNPs at fourfold-degenerate sites. Phylogenetic tree was constructed using IQ-TREE with the best model TVM + F + ASC + R8. Clades with bootstrap values of above 50% are indicated by a circled blue dot. b PCA plot of 50 B. napus landraces and 119 B. oleracea accessions. c Model-based Bayesian clustering of 50 B. napus landraces and 119 B. oleracea accessions performed using STRUCTURE 2.1 with the number of ancestry kinships (K) set to 2, 3, or 4. Each accession is denoted by a vertical bar composed of different colors in proportions corresponding to its proportion of genetic ancestry from each of these ancestral populations. Source data are provided as a Source Data file

Demographic modeling, using ∂a∂i20 and fastsimcoal221, supported the aforementioned results, and the log-likelihood values of the two optimal models were −11,826 and −4,194,976 (model a in Supplementary Fig. 2, model e in Supplementary Fig. 3). The best model in fastsimcoal2 also suggested that a gene flow event from European turnip to the B. napus A subgenome occurred ~106–1170 years ago (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Principal component analysis (PCA; Fig. 2b) located B. napus landraces (n = 50, registration date before 1980) near the European turnip (n = 33; Fig. 2b). Population structure analysis revealed that two population clusters (K = 2) represent the optimal model (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Fig. 4), which clearly separate B. napus landraces and European turnip from other B. rapa subspecies, supporting the evolutionary history of the B. napus A subgenome6.

In the BolC ML tree, the B. napus accessions were closest to a B. oleracea branch comprising four subspecies-kohlrabi (B. oleracea var. gongylodes), broccoli (B. oleracea var. italica), cauliflower (B. oleracea var. botrytis), and Chinese kale (B. oleracea var. alboglabra)–suggesting that the B. napus C subgenome might have evolved from the common ancestor of these lineages (Fig. 3a). To validate this result, we performed demographic analyses using ∂a∂i20 and fastsimcoal221 (Supplementary Figs. 3, 5). The ∂a∂i results supported the model that the B. napus C subgenome evolved from the common ancestor of kohlrabi, broccoli, and cauliflower (log-likelihood=−6806). In the fastsimcoal2 results, model a, which suggests that the B. napus C subgenome originated from the common ancestor of kohlrabi, cauliflower, and broccoli, was supported with a much higher log-likelihood (Δ = 460,3200; log-likelihood=−2,975,039) than model b, suggesting that the B. napus C subgenome originated during divergence of ancestors of four B. oleracea subspecies.

Considering that migration events may have occurred at three different stages (recent, medium- and long-term), five models (models c–g) were compared to infer the evolutionary history of the B. napus C subgenome. Our data support model c (log-likelihood=−2,914,388), indicating that the ancestor of B. napus split from the common ancestor of four B. oleracea subspecies, with recent gene flow into B. napus ~108–898 years ago (Supplementary Fig. 6).

In the PCA plot, kohlrabi (n = 19) was the closest subspecies to B. napus landraces, followed by Chinese kale, broccoli, and cauliflower (Fig. 3b), suggesting that B. napus landraces were closer to the four B. oleracea subspecies. The optimal number of population clusters of B. napus landraces and B. oleracea was identified as K = 2 (Fig. 3c; Supplementary Fig. 4b), representing distinct B. napus and B. oleracea clusters, indicating that the B. napus C subgenome has a more complex origin than A subgenome.

The Cruydt Boeck recorded the early form of winter B. napus and noted that its raepolie was used as lamp fuel7. To validate this record, we compared the linkage disequilibrium (LD) decay of different groups, based on progenitors of the A and C subgenomes (33 accessions of European turnip and 66 accessions of four B. oleracea subspecies) and B. napus accessions in the three SNP sets (Supplementary Table 2). At a threshold of r2 = 0.3, the LD decay in B. rapa (2.10 kb) and B. oleracea (27.90 kb) was stronger than those in the A (19.30 kb) and C (1365.30 kb) subgenomes of B. napus, respectively (Supplementary Table 2; Supplementary Figs. 7–9), supporting a strong bottleneck developed in both two subgenomes during B. napus evolution. In the Bna SNP set, the oilseed B. napus showed stronger LD decays than did fodder and vegetable accessions, and the LD decays of winter type were also stronger than those of the spring and semi-winter types (Supplementary Table 2).

We estimated the historical effective population sizes (Ne) and divergence times for different ecotypes and usages of B. napus using SMC++22. The Ne values for different B. napus ecotypes showed similar dynamics (Supplementary Fig. 10). The estimated time of B. napus formation was ~1912–7178 years ago. The winter and semi-winter B. napus ecotypes diverged ~60 years ago, whereas the winter and spring B. napus diverged ~416 years ago, and oilseed and non-oilseed B. napus diverged ~277 years ago. These results are consistent with historical records8,9. Based on the aforementioned results, we could speculate that winter oilseed was the original B. napus.

Selection signals under improvement of B. napus

We divided the B. napus improvement process into two stages after B. napus origin. The first stage of improvement (FSI) was the process from original B. napus to landrace, while the second stage of improvement (SSI) represented the improvement from landraces to improved cultivars. As no wild B. napus populations are known7, we pooled two groups of progenitors, European turnip (n = 33) and four B. oleracea subspecies (n = 66), to represent the pseudo-wild ancestral A (denoted AA) and C (denoted CA) subgenomes of B. napus, respectively. To avoid the influence of introgression derived from non-ancestors of progenitors, we identified FSI-selection signals from the shared variations between B. napus landraces and their ancestors by comparing genomic variations with high fixation index (FST) and reduction of diversity (ROD) between the A subgenome of B. napus landraces (denoted AL) and AA, and between the C subgenome of B. napus landraces (denoted CL) and CA, using B. napus landraces as the derived group and progenitors as the control group. SSI-selection signals were detected by comparing B. napus landraces with improved cultivars (n = 95, registration date after 2000) and by comparing cultivars with different ecotypes.

Nucleotide diversity (π) decreased from 7.23 × 10−4 in AA to 5.40 × 10−4 in AL and from 7.45 × 10−4 in CA to 4.97 × 10−4 in CL (Supplementary Data 8 and 9), implying that during the FSI more genetic diversity was lost in the B. napus C subgenome than in the A subgenome. The FST(AL/AA) was 0.136 (Supplementary Data 10), lower than FST(CL/CA) (0.246) (Supplementary Data 11). Notably, both FST(AL/AA) and FST(CL/CA) were higher than FST(improved cultivar/landrace) (0.016) (Supplementary Fig. 11; Supplementary Data 12), suggesting that less genetic differentiation occurred during the SSI than during the FSI. This difference is most likely attributable to the most noteworthy event in the breeding history of B. napus: namely the widespread use of the erucic-acid-free variety Liho and the low-glucosinolate variety Bronowski to breed cultivars with zero erucic acid and low glucosinolate23.

Calculation of the z transformations of FST and ROD detected 424 and 366 common FSI-selection windows, corresponding to 66 and 44 selection signals in the A and C subgenomes, respectively (Supplementary Figs. 12, 13; Supplementary Data 13 and 14). In the outlier regions, we retrieved 1522 genes in AL and 811 genes in CL (Supplementary Data 15 and 16), respectively.

Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis revealed that genes in the FST and ROD overlapping outliers of the A subgenome were enriched in three groups of GO classifications, including stress tolerance (response to herbivore (GO:0080027), abscisic acid metabolic process (GO:0009687), and regulation of immune response (GO:0050776)), development (axillary shoot meristem initiation (GO:0090506) and meristem initiation (GO:0010014)), and metabolic pathways (unsaturated fatty acid biosynthetic process (GO:0006636), triglyceride biosynthetic process (GO:0019432) and terpenoid metabolic process(GO:0006721)) (Supplementary Data 17), whereas those of the C subgenome were over-represented in development process, photomorphogenesis (GO:0009640), trichome morphogenesis (GO:0010090), regulation of cell proliferation (GO:0042127), and inflorescence development (GO:0010229; Supplementary Data 18). These results suggest that A subgenome-specific selection may have promoted the stress tolerance and oil accumulation during the FSI of B. napus, whereas improvement of its developmental traits may have been due to asymmetrical selection in the C subgenomes.

Regarding SSI-selection signals, we identified 912 outliers (corresponding to 79 selection signals spanning 16.35 Mb) simultaneously detected by at least three of the four comparisons (FST, ROD, XP-CLR, and XP-EHH) (Fig. 4a–d; Supplementary Fig. 14; Supplementary Data 19). The 2610 genes identified in the overlapping regions were over-represented in phloem glucosinolate transport (GO:1901349) and glucosinolate biosynthetic process (GO:0019761) — representing key genes whose silencing might have contributed to the reduced seed glucosinolate content of elite B. napus (Supplementary Data 20 and 21). These genes were also enriched in sucrose transport (GO:0015770), RNA splicing (GO:0008380), and pollination (GO:0009856), indicating that not only seed quality but also fertility, energy utilization efficiency, and post-transcriptional regulation were improved in the breeding programs. In addition, 84 selection signals between double-high (high erucic acid and glucosinolate) and double-low (low erucic acid and glucosinolate) cultivars were merged from 1417 overlapping outlier windows (Supplementary Fig. 15; Supplementary Data 22 and 23), and had similar GO enrichment to that in the SSI. We determined that the reproductive system of B. napus may have been optimized, as genes in the outliers were also enriched in the reproductive process (GO:0022414), reproductive structure development (GO:0048608) and regulation of secondary shoot formation (GO:2000032) (Supplementary Data 24).

Genome-wide scanning and annotations of selected regions during the SSI of B. napus. a, d Genome-wide screening of SSI-selection signals with ROD and FST. ROD and FST were normalized as z scores for B. napus. A 100-kb sliding window with an increment of 10 kb was used to calculate these values. Each point represents a value in a 100-kb window. Horizontal dashed lines show the significance level of α = 0.05, corresponding to z = 1.645. The glucosinolate transport genes in the selection outlier regions are labeled in red, and erucic acid biosynthesis genes are in blue. b, e Expression patterns of two GTR2 and FAE1 family members. Genes in the selection outlier regions during the SSI are in red. DH double-high accession Zhongyou821, DL double-low accession Zhongshuang11, Ro root, St stem, Le leaf, Fl flower, Se7d, 10d, 14d, and 45d seeds at 7, 10, 14, and 45 days after flowering, SP7d, 10d, and 14d silique pericarp at 7, 10, and 14 days after flowering. c, f GWAS results of total glucosinolate and erucic acid content that overlapped selection signals. Dashed horizontal lines depict the significant (−log10(P) = 6.61) and suggestive (−log10(P) = 5.31) thresholds. The lower panel shows the LD blocks of significantly associated loci in GWAS. Source data are provided as a Source Data file

Furthermore, candidate genes involved in glucosinolate transport and fatty acid elongation were located within syntenic regions in the A and C subgenomes (Supplementary Data 20 and 23), implying that parallel subgenomic selection may have contributed to improved seed quality.

Genome-wide association studies

To identify candidate genes responsible for 11 important traits, we conducted multi-locus random mixed linear model analysis for genome-wide association studies (GWAS) using mrMLM v1.324. To obtain high-quality SNPs, we performed imputation for the Bna SNP set, and retained 670,028 SNPs with a MAF of >5% for GWAS. Comparison between imputation results for 19 polymorphic nucleotides and Sanger sequencing results indicated that 98.74% of imputed genotypes were correct (Supplementary Data 25). The average correlations (r2) between imputed and true genotypes for two biological replicates of 20 accessions was 0.956 with minimum and maximum values ranging from 0.928 to 0.967 (Supplementary Fig. 16), further confirming the accuracy of the imputed genotypes. Using the Genetic Type I Error Calculator (GEC)25, the effective number of independent SNPs was 206,001, and the P-value thresholds used to identify significant loci were set at 2.43 × 10−7 [significant, 0.05/n, −log10(P) = 6.61] and 4.85 × 10−6 [suggestive, 1/n, −log10(P) = 5.31].

In total, we identified 60 loci significantly associated with 10 target traits, including 5 related to seed yield, 3 to silique length, 4 to oil content, and 48 to seed quality (Fig. 4c–f; Fig. 5b; Supplementary Fig. 17; Supplementary Data 26). In addition, three loci were shown to be associated with flowering time at the suggestive threshold. SNPs significantly associated with seed quality traits explained 14.30–35.47% of the phenotypic variance, higher than those for seed yield (16.81%) and oil content (20.64%). Most loci that were associated with seed quality in a previous GWAS26 were also detected here. As traits related to oil content and yield are complex and easily affected by environmental variation, we integrated the significant loci from this study with quantitative trait loci (QTLs) identified previously27,28. Candidate genes controlling different traits thus were identified based on functional annotation and transcriptome analysis in intersecting regions of selection outliers and QTL, as discussed below.

Overview of flowering-time regulation under the selection of the ecotype improvement of B. napus. a Genome-wide screening of ecotype improvement selection signals of FST (semi-winter/winter) and FST (spring/winter). Flowering-time genes simultaneously identified in selection outlier regions between winter and spring ecotypes, and between winter and semi-winter ecotypes are labeled in red in the corresponding chromosomes. Full descriptions of these genes are shown in Supplementary Data 36. Three LD blocks containing significant GWAS associations for flowering time are labeled in black. b GWAS results of flowering time that overlapped with selection signals. Dashed horizontal lines depict the significant (−log10(P) = 6.61) and suggestive (−log10(P) = 5.31) thresholds. Lower panel shows the LD blocks of significantly associated loci in GWAS. c Major flowering-time pathways and selective effects acting on their components during ecotype improvement. Brown and green rounded rectangles represent proteins involved in positive and negative regulation of flowering time, respectively. Flowering integrator proteins are shown in brown and green dots, respectively. Red dots at the top right of gene symbols represent flowering-time-regulation genes simultaneously identified in the selection outlier regions both semi-winter/winter and spring/winter comparisons, and purple and blue dots represent those of spring/winter and semi-winter/winter comparisons, respectively. Source data are provided as a Source Data file

Transcriptome analysis

To identify differentially expressed SSI-related genes, we harvested 11 tissues from a high-oil-content and double-low cultivar Zhongshuang11 and a low-oil-content and double-high cultivar Zhongyou821. After filtering, 848,776,815 125-bp paired-end reads were obtained, containing 212.19 Gb of data. On average, 82.64% of the reads uniquely mapped to the B. napus reference genome (Supplementary Data 27)5. The highest number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (Supplementary Fig. 18) was detected in seeds at 45 days after flowering (Se45D), with 9962 up- and 12,441 down-regulated genes. The lowest number of DEGs occurred in Se14D, when only 2420 genes were differentially expressed.

Genes that were down-regulated in the stem (St), leaf (Le), and silique pericarp at 7 (SP7D), 10 (SP7D), and 14 (SP7D) days after flowering in Zhongshuang11 were significantly over-represented in the glucosinolate biosynthetic process (GO:0019761; Supplementary Figs. 19–29; Supplementary Data 28), indicating that the lower seed glucosinolate content in the double-low accession was likely caused by reduced glucosinolate biosynthesis. In silique pericarp, up-regulated genes were significantly over-enriched in the fatty acid biosynthetic process, suggesting that the silique pericarp may also play an important role in increasing seed oil content.

Major genes improving environmental adaption

During the FSI, defense responsive genes may play key roles in B. napus environmental adaptation. In the A subgenome, we identified 6, 5, 6, and 14 genes associated with drought tolerance, herbivore resistance, responses to mechanical stimulus, and immune responses, respectively (Supplementary Data 29). Among the genes related to drought tolerance, NCED3 (Bra001552) plays a major role in the regulation of ABA (abscisic acid) biosynthesis in response to water deficit29. Besides, NCED5 (Bra032359) contributes, along with NCED3, to ABA production, thereby affecting plant growth and water stress tolerance30.

Endogenous ABA is rapidly produced during drought, inducing stomatal closure and thereby enhancing drought tolerance. A subgenome-specific selection on ABA biosynthesis pathway genes might have been important for enhancing drought tolerance during the FSI of B. napus, and laid a solid foundation for its cultivation in diverse environments. Other candidate genes involved in ABA metabolism, are also noteworthy, such as CYP707A3 (Bra021965 and Bra025083), XERICO (Bra013211), and PHYB (Bra001650), all of which are associated with drought stress responses, via regulation of ABA accumulation (Supplementary Data 29).

In addition, A subgenome-specific selection also contributed to disease resistance improvement during the FSI of B. napus. In the selection regions, NPR3 (Bra025093) is one of the notable genes. As a receptor for the immune signal salicylic acid in plants, NPR3 controls the proteasome-mediated degradation of NPR1, which is involved in negative regulation of defense responses against bacterial and oomycete pathogens31. Similar defense-responsive genes, BAH1(Bra032581), NHL25 (Bra028103), and NDR1 (Bra035766) are also involved in regulating plant innate immunity to microbes (Supplementary Data 29) and may have contributed to biotic stress during the FSI of B. napus.

Major genes improving seed quality

In B. napus, seed oil contains 50% erucic acid and high levels of glucosinolates that significantly reduce nutritional value. Selection signatures and GWAS results (Fig. 4c–f) implicate several candidate genes associated with seed erucic acid and glucosinolate content.

Glucosinolates are synthesized in rosette leaves and silique walls and subsequently relocated to the embryo through the phloem by transporters. We identified the glucosinolate-specific transporter, GTR2, as likely responsible for glucosinolate delivery from source tissues into seeds in B. napus32. Among the eight Bna.GTR2 genes, three (BnaC02g42280D, BnaA09g06180D, and BnaA09g06190D) are silenced in the seeds of the double-low cultivar, and the other five are moderately expressed (Fig. 4b); of these, three (BnaA02g33530D, BnaC02g42260D, and BnaC09g05810D) are located in major QTL regions. Further reduction of anti-nutritional glucosinolates, in B. napus seeds, may be achieved through silencing these five GTR2 genes, especially those located in major QTL regions.

Four GWAS signals associated with erucic acid were identified during the SSI, including two on chromosomes A08 (BnaA08g11130D) and C03 (BnaC03g65980D) (Fig. 4) near the active FATTY ACID ELONGASE 1 (FAE1) genes whose products control erucic acid synthesis from oleoyl-CoA (C18:1-CoA)33. These two genes were significantly highly expressed in the high-erucic acid cultivar, suggesting that FAE1 silencing is an important contributor to reduced seed erucic acid content. Additional GWAS signals associated with erucic acid were on chromosome C02 and C07, (Fig. 4), near AMP-DS (BnaC02g42510D) and ATGLL (BnaC07g30920D) and may represent SSI-selection genes whose products reduce seed erucic acid.

Genes involved in ecotype improvement of B. napus

Based on vernalization requirement, B. napus is divided into winter (requiring a prolonged cold period), semi-winter (requiring a short cold period), and spring (no cold requirement) ecotypes. The original B. napus was a winter oilseed; spring and semi-winter ecotypes were developed for adaptation to different environments. To identify candidate genes responsible for ecotype improvement, we scanned the selection outliers using the winter ecotype as the control and the spring and semi-winter ecotypes as derived groups (Fig. 5a; Supplementary Figs. 30−31). Comparisons between B. napus winter and semi-winter, and between winter and spring ecotypes detected 1996 and 1117 overlapping outlier windows, including 4548 genes in 156 selection regions and 2729 genes in 107 selection regions, respectively (Supplementary Data 30−33). The majority of selection regions were located in the C subgenome, and only 32 and 21 were distributed on the A subgenome, respectively, suggesting that ecotype improvement was mainly caused by asymmetrical subgenomic selection. Besides, 844 outlier windows corresponding to 72 selection regions were overlapped between two ecotype improvement analyses, these parallel selection signals might contribute to local adaption of B. napus.

Genes in the ecotype improvement selection regions were over-represented in maintenance of floral organ identity (GO:0048497), floral organ abscission (GO:0010227), and regulation of floral meristem growth (GO:0010080), suggesting that these SSI-selection signals might be critical for local environmental adaptation of B. napus (Supplementary Data 34 and 35).

We retrieved 306 genes related to flowering time in A. thaliana from FLOR-ID (FLOweRing Interactive Database)34 and identified 1225 orthologs in B. napus. Among the 24 flowering-time genes simultaneously located within outlier regions of the two comparisons (Fig. 5a–c), 22 of which were distributed on the C subgenome and regulating flowering time mainly through vernalization and photoperiod pathways (Supplementary Data 36). In particular, the FLC locus and its chromatin-mediated regulators will be the most promising targets for regulating flowering time of B. napus.

In the vernalization pathway, FLC (BnaC02g00490D) encodes a core regulator in B. napus ecotype improvement (Fig. 5c), as the product of the homologous Arabidopsis thaliana FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC) is an important repressor of floral transition35. A recent study reported that different FLC paralogs contribute differentially to natural variation in B. napus flowering time, and that a 2.833-kb insertion in BnFLC.A2 and its homeologous exchange (HE) with BnFLC.C2 generated early-flowering B. napus ecotpyes36. Our GWAS detected three loci associated with flowering time at the suggestive threshold (Fig. 5b). Interestingly, two FLC genes on chromosome A02 and C02, located within the two LD blocks (hFT-1 and hFT-2) controlling flowering time variation, each explained ~8% of the total phenotypic variance (Supplementary Data 27). These results further confirmed the importance of FLC during ecotype improvement.

Genes involved in chromatin modification also experienced extensive selection for ecotype improvement, via regulation of FLC expression (Fig. 5a–c), such as FLC activator gene SSRP1 (BnaC02g37430D), encoding components of the facilitates chromatin transcription (FACT) complex, and FLC repressor gene VRN2 (BnaC01g21540D), encoding a component of the polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2).

In Arabidopsis, the histone chaperones SSRP1 in the FACT complex assist the progression of RNA polymerase II and promote FLC expression37. In contrast, VRN2 plays a critical role in maintaining transcriptional repression of FLC, after vernalization, by regulating the deposition of H3K27me3 and H3K9me3 repressive marks at the FLC locus38. These results suggest that epigenetic variations, especially histone modifications involved in regulating FLC expression, are closely associated with flowering time in B. napus. These genes therefore represent promising regulatory targets in future B. napus breeding programs (Fig. 5c; Supplementary Data 36).

Major genes for seed oil content and seed yield

Seed oil content may have been greatly improved during the FSI of B. napus. We detected 9 FSI selection signals that overlapped with oil content QTLs (Supplementary Data 37). In these overlapping regions, two genes were involved in fatty acid synthesis, one in triacylglycerol biosynthesis, and seven in fatty acid elongation. For example, (KASI) on chromosome A02 (Supplementary Data 20 and 23) encodes a protein that may be crucial for fatty acid synthesis and also plays a role in chloroplast division and embryo development39.

Mutation of Arabidopsis KASI disrupted embryo development and dramatically reduced fatty acid levels in seeds. Bna.FATA1 (BnaA03g37700D) is an ortholog of Arabidopsis FATA ACYL-ACP THIOESTERASE 1 on chromosome A03 (Supplementary Data 20 and 23) whose product controls termination of intraplastidial fatty acid synthesis by hydrolyzing the acyl-ACP complexes. Mutation of two Arabidopsis FATA genes reduces FATA activity, affecting oil content and seed fatty acid composition40.

B. napus seed yield is influenced by silique length and shoot branching. We detected three loci significantly associated with silique length. The peak of significant SNP-trait associations was located at 27.99 Mb on chromosome A09, near a 165-bp deletion in ARF18 that is associated with increased seed weight and silique length, via maternal regulation41. We also identified two pairs of parallel SSI-selection signals in double-low B. napus cultivars. The orthologs of Arabidopsis BRC142 on chromosomes A01 and C01 and DOF4.443 on chromosomes A08 and C03 (Supplementary Data 23) may encode key regulators of shoot branching and silique development in outlier regions. Hence, manipulating genes associated with seed oil content and seed yield within the SSI-selection signals and of candidate genes identified by GWAS should have practical applications in B. napus breeding for high yield and oil content.

Discussion

In this study, we developed a large genome variation data set for genetically diverse B. napus accessions, which provided an opportunity to finely resolve the origin and evolutionary history of B. napus. Based on aforementioned analyses, we posit that the B. napus was originated from the hybridization between domesticated B. rapa and B. oleracea ~1910–7180 years ago (Supplementary Fig. 32), which accorded with previous conclusions (~6700 and 7500 years ago) derived from Ks estimation4,5. The B. napus A subgenome evolved from the ancestor of European turnip; and the B. napus C subgenome might have evolved from the common ancestor of kohlrabi, cauliflower, broccoli, and Chinese kale. In addition, the LD and demographic analyses support that the original B. napus was winter oilseed, and the spring and semi-winter B. napus developed ~416 and ~60 years ago, and non-oilseed B. napus developed ~277 years ago (Supplementary Fig. 32). These results are consistent with historical records, which indicate that spring B. napus developed around the year 17008, and that the semi-winter ecotype has only a short history in China, and arose from the winter ecotype, which was introduced from Europe in the 1930–1940s9. In recent 1000 years, gene flow from two progenitors into B. napus also occurred occasionally, leading to improvement of complex traits in B. napus.

Previous archeological and linguistic lines of evidence suggest that turnip is likely the first domesticated B. rapa in the European-Central Asian region44,45. A recent demographic inference further supported an eastward series of B. rapa domestication events, over the past several thousand years, and rapini (B. rapa ssp. sylvestris), which split from the European-Central Asian B. rapa (European turnip) cluster, ~3715–6190 years ago, is not likely a wild B. rapa46. Since the estimated origin times of B. napus in previous and our studies were all earlier than the divergence time between rapini and the European-Central Asian B. rapa, European turnip might be the only possible A subgenome donor for B. napus formation, as the first domesticated B. rapa. Sampling of more wild B. rapa and B. oleracea relatives would be helpful for better understanding the complex events that occurred during B. napus origin. Noting prior evidence that the maternal ancestor of B. napus was highly unlikely to be B. oleracea1, we posit that B. napus resulted from hybridization between a maternal ancestor of European turnip and a paternal common ancestor of the four aforementioned B. oleracea subspecies.

During the FSI, A subgenome-specific selection on defense-response genes greatly improved B. napus with regard to adaptation to environmental variation, reflecting the fact that strong survival pressure may often be the first challenge to a newly evolved plant species. Furthermore, the improvement of oil accumulation in B. napus resulted mainly from A subgenome-specific selection on triglyceride biosynthetic genes. This is similar to the history of upland cotton, whose D-subgenome-specific selection led to prolonged fiber elongation in cultivated cottons47, suggesting that asymmetrical subgenomic selection may often occur during the FSI.

Artificial breeding of B. napus dramatically reduced its genetic diversity and affected SSI-selection signals. Combining this information with GWAS results and previous QTL information, we identified a number of outlier regions and candidate genes associated with seed yield, seed oil, glucosinolate, and erucic acid contents and flowering time. Similarly, improvement of seed quality due to subgenome parallel selection was also observed during the artificial selection of B. napus.

Our study provides a valuable resource for understanding the origin and improvement history of B. napus and will facilitate the dissection of the genetic bases of important agronomic complex traits. The significant SNPs associated with favorable variants, selection signals, and candidate genes will be a valuable resource for further improving the yield, seed quality, oil content, and adaptability of this recent allopolyploid crop and its relatives.

Methods

Plant materials

The diversity panel used in this study comprised 588 B. napus accessions, including 466 from Asia, 102 from Europe, 13 from North America, and 7 from Australia (Supplementary Table 1; Supplementary Data 1). Based on growth habit records, these materials were divided into three ecotypes; spring (86 accessions), winter (74 accessions), and semi-winter (428 accessions). As there is no precise definition for the B. napus landrace, the B. napus accessions registered before 1980 and after 2000 were regarded as landraces and improved cultivars, respectively, for the purpose of investigating the selection signals during the FSI and SSI of B. napus. Detailed information of the 588 accessions is listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Sequencing and discovery of genomic variations

Prior to sequencing and phenotyping, all B. napus accessions were maintained by self-pollination for at least four generations at the Chongqing Rapeseed Engineering Research Center, Chongqing, China. Genomic DNA was extracted from the two youngest leaves on a single plant of each accession. DNA libraries with a mean insert size of 350 bp were constructed, and 125-bp paired-end reads were generated using an Illumina HiSeq 4000 instrument. Library preparation and sequencing were carried out at the Biomarker Technologies Corporation (Beijing, China). Two biological replicates for 20 accessions were selected for whole-genome resequencing to assess the accuracy of sequencing in this study.

The resequencing data for 199 B. rapa and 119 B. oleracea accessions published previously were retrieved from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database. Low-quality bases from paired-reads were trimmed using Trimmomatic (version 0.33)48, with the parameter LEADING:3 TRAILING:3 SLIDINGWINDOW:4:15 MINLEN:80. To investigate the origin of B. napus, the genome sequences of B. rapa (version 1.5)15 and B. oleracea (version 1.0)16 were merged as a B. napus ancestral pseudo-genome. Filtered B. napus sequencing reads were aligned to the B. napus reference genome (version 4.1)5 and the B. napus ancestral pseudo-genome, and B. rapa and B. oleracea sequencing reads were mapped only to their corresponding reference genomes using the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (version 0.7.10-r789)49. Local realignment, duplicate read marking, and base quality recalibration for the alignment results were further processed sequentially using Picard (release 2.0.1, http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/) and GATK (version 3.2–2-gec30cee)50. SNP and InDel calling for each sample were performed using SAMtools’s mpileup (version 0.1.19–44428cd) and GATK with the parameter–ts_filter_level 90. To remove false variants, only biallelic SNPs simultaneously detected by both methods were retained, using the function SelectVariants in GATK with the following parameters:–filterExpression QD < 2.0 || FS > 60.0 || MQ < 40.0–clusterWindowSize 5–clusterSize 2; SNPs with minor allele frequency (MAF) of lower than 5% in the population were discarded. A total of 103 SNPs were randomly selected for accuracy validation of SNP calling using conventional PCR and Sanger-based sequencing (Supplemental Table 5) in 20 B. napus accessions.

To reveal the original subtaxa of B. rapa and B. oleracea involved in the formation of B. napus, A (BraA) and C subgenome (BolC) SNP sets were obtained as the following procedure. We mapped the B. napus resequencing data onto the B. napus ancestral pseudo-genome to call SNPs, which were split into two SNP sets based on the two subgenomes. Then, the SNPs retrieved from the B. rapa or B. oleracea resequencing data using corresponding genomes as reference were combined with two SNP sets obtained previously to represent BraA and BolC SNP sets, respectively. To perform selective sweep analysis and GWAS in B. napus, the SNPs called from B. napus resequencing data (Bna) using the B. napus genome as reference were also obtained.

Phylogenetic analysis and population structure analyses

To construct maximum likelihood (ML) trees, we screened 17,000, 19,377, and 19,548 SNPs at fourfold-degenerate sites (MAF > 5%) from the BraA, BolC, and Bna SNP sets, respectively. We generated three ML trees using IQ-TREE v1.6.619, according to the best model determined by the Bayesian information criterion (BIC). The reliability of the ML trees was estimated using the ultrafast bootstrap approach (UFboot) with 1000 replicates. An online tool Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v3 (https://itol.embl.de)51 was used to display the consensus ML trees. Principal component analysis of the three SNP sets was performed using EIGENSOFT (version 6.1.4)52.

We inferred the population structure of 50 B. napus landraces and two progenitors, 199 B. rapa and 119 B. oleracea accessions, using STRUCTURE53, with two subsets of SNPs (7668 and 10,396 SNPs with MAF>5% obtained from BraA and BolC, respectively; 1 SNP per 40 kb) evenly distributed throughout the reference genomes. Each K value, as a putative number of populations set from 1 to 10, was obtained with five independent runs. The length of the burn-in period and number of MCMC replications after burn-in were set to 50,000 and 100,000, respectively. The optimum number of subgroups (K) was determined based on the log probability of the data (lnP(K)) and an ad hoc statistic ΔK method54.

Demographic history of B. napus

To assess whether the B. napus C subgenome originated from the common ancestor of the four aforementioned B. oleracea subspecies, the B. napus C subgenome originated from the ancestor of European turnip, and whether and when migration into B. napus occurred, we investigated the demographic history using both diffusion approximations for demographic inference (∂a∂i) version 1.7.020 and fastsimcoal2 v. 2.6.0.321. To mitigate the effect of LD, one SNP per 10 kb was selected, and SNPs located 10 kb away from genes were used to convert into a site frequency spectrum (SFS) using easySFS (https://github.com/isaacovercast/easySFS).

Five and seven models (Supplementary Figs. 3, 5) representing demographic history of B. napus A and C subgenomes were respectively evaluated using fastsimcoal221. To ensure convergence, we ran fastsimcoal2 50 times, and kept the run that resulted in the highest log likelihood for each model. Estimates were obtained from 100,000 coalescent simulations per likelihood estimation (-n100,000) and 40 Expectation/Conditional Maximization cycle (-L40). The best model with the maximum likelihood was retained. We estimated 95% confidence intervals (CI) using parametric bootstrap estimates based on 80 data sets simulated according to Conditional Maximum Likelihood estimates in the best model estimation parameters. The optimal demographic models obtained from fastsimcoal2 were also validated using ∂a∂i20. Since up to three subpopulations can be handled in ∂a∂i at a time, three demographic models for both B. napus two subgenomes were compared. The best fitting model was selected with the highest log-likelihood under the best-fit parameter set.

To better understand the original form of B. napus, we used SMC++22 to estimate the divergence time and historical Ne among different ecotype and usage of B. napus. In the demographic analyses, generation estimates were inferred by assuming that the upper and lower mutation rates were 1.5 × 10–8 and 9 × 10–9 per synonymous site per generation, respectively, and that the generation time was 1 year46.

Calculation of linkage disequilibrium

Linkage disequilibrium (LD) between pairs of SNPs up to 100 kb apart on each chromosome were estimated as the correlation coefficient (r2) using PLINK v1.0755, LD decay statistics were calculated for different (sub)populations, and LD decay graphs were plotted using PopLDdecay3.26 (https://github.com/BGI-shenzhen/PopLDdecay), with the parameter -MaxDist 1000 for SNP set BraA, and -MaxDist 5000 for SNP sets BraC and Bna.

Measurement of agronomic traits

All accessions evaluated in this study were cultivated in field trials in Beibei, Chongqing, China (29°45′ N, 106°22′ E, 238.57 m) during the 2013 and 2014 growing seasons. A randomized complete block design with three replications was employed. Each accession was grown in three rows of 10 plants per row, with a distance of 20 cm between plants and 30 cm between rows. Open-pollinated seeds were harvested from five randomly selected plants for measurements of seed yield per plant (SY) and silique length (SL). Oil content (OC), seed color (SC), and total glucosinolate content (GC) were detected by near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy (NIRS) analysis. The fatty acids palmitic acid, stearic acid, oleic acid, linoleic acid, linolenic acid, eicosenoic acid, and erucic acid were quantified by gas liquid chromatography, according to a previous report26. The flowering time (FT) was defined as the day on which the plants reached Biologische Bundesanstalt, Bundessortenamt and CHemical (BBCH) stage 6156.

Genome-wide selective sweep analysis

To identify candidate regions potentially affected by selections, nucleotide diversity (π), and population fixation statistics (FST) were calculated using vcftools (v0.1.13, https://vcftools.github.io) in a 100-kb sliding window with a step size of 10 kb. π is the expected heterozygosity per site derived from the average number of sequence differences in a group of samples, and FST is the inbreeding coefficient of a subpopulation, used for estimating the degree of pairwise genomic differentiation on candidate genes between pairs of subpopulations. The reduction of diversity (ROD) values were calculated based on the ratio of π for a subpopulation with respect to a control subpopulation. All the output results of ROD and FST were standardized and transformed into z-scores using a 100-kb sliding window with a 10-kb step size. The outlier windows of ROD (high values), and FST (high values), which characterize candidate genes involved in the FSI and SSI of B. napus, were determined by z-tests with a significance level of α = 0.05 corresponding to a z-score of 1.645.

To identify additional SSI effects, we also calculated the XP-CLR and cross-population extended haplotype homozygosity (XP-EHH) using XP-CLR v1.0 (–w1 0.005 200 10000–p0 0.95)57 and selscan v1.2.158, respectively. In the two programs, all the Bna SNPs were assigned genetic positions based on a published genetic map. Windows with the top 5% of maximum XP-CLR or XP-EHH values were considered as selection regions. Candidate genes involved in the domestication B. napus were identified from the selection regions detected by at least two methods, and those for SSI were identified from common selection regions detected by at least three methods.

In the FSI-selection analysis, European turnip (n = 33) and B. oleracea (n = 66) involved in the original formation of B. napus versus B. napus landraces and the SNP sets BraA and BolC were used to detect FSI events. The improvement signals were detected based on the Bna SNP set and the following three pairwise comparisons: first, B. napus landraces versus improved cultivars to identify SSI events; second, double-low versus double-high B. napus accessions to identify selection signals related to seed quality improvement; third, comparisons between spring and winter ecotype, and between spring and winter ecotype to identify selection signals associated with ecotype improvement.

Genotype imputation and accuracy estimation

In the case of low-depth sequencing (~5×), genotyping calling errors are inevitable, particularly at sites of low MAF. To improve the mapping resolution for GWAS, imputation for sporadic missing genotypes in the Bna SNP set was implemented in Beagle v.4.159 with default parameter settings and 50 iterations in a sliding window of 50,000 SNPs. Pedigree and reference information were not used in the imputation procedure. Imputation accuracy was estimated using two measures. One is the comparison of the imputation results of 19 polymorphic nucleotides with the corresponding Sanger sequencing results (Supplementary Data 32). The other was the correlations (r2) between imputed and true genotypes, which were calculated at each locus for 20 accessions of biological replicates (R021–R040, Supplementary Data 1) in intervals of 5% of MAF. Missing SNPs in the true genotypes were excluded when calculating the correlations.

Genome-wide association study

The best linear unbiased prediction (BLUP) for each investigated trait of each accession was obtained using an R script (www.eXtension.org/pages/61006), based on a linear model and corresponding traits with three replicates over 2 years. The resulting values were used as phenotypes for the association analysis. The multi-locus random-SNP-effect mixed linear model was used to test trait-SNP associations in mrMLM v1.324; PCA and K were controlled as fixed and random effects, respectively. The effective number (n) of independent SNPs was calculated using GEC software25. Significant (0.05/n, Bonferroni correction) and suggestive (1/n) and P-value thresholds were set to control the genome-wide type I error rate. To identify reliable significant association signals in our GWAS, only LD blocks containing at least one significant and one suggestive SNPs were regarded as significant loci.

Transcriptome and gene ontology enrichment analyses

Total RNA was isolated from 11 tissues of two representative accessions with different oil contents and seed qualities (Zhongshuang11, a high-oil-content, double-low accession; and Zhongyou821, a low-oil-content, double-high accession). Tissues from roots (Ro), stems (St), mature leaves (Le), and flowers (Fl) were harvested at flowering stage 63–65 as defined in the BBCH56. Seeds (Se) and silique pericarps (SP) on the main inflorescence were harvested 7, 10, 15, and 45 days after flowering. For each sample, two biological replicates, each replicate obtained from three independent plants, were pooled for transcriptome sequencing.

Library preparation, sequencing, and read filtering of 44 libraries (11 tissues × two accessions × two biological replicates per sample) were conducted by the Biomarker Technologies Corporation (Beijing, China). Filtered reads were then mapped to the B. napus reference genome using STAR 2.4.2a with default parameters60. Gene expression levels were quantified by the cuffquant program in terms of fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM)61. The DEGs were then detected in each tissue between two accessions using the cufdiff program, with the following standards: FDR < 0.01 and absolute fold change >2.

Gene ontology enrichment analysis

Gene ontology (GO) terms for all B. rapa, B. oleracea, and B. napus proteins were assigned based on BLASTP analysis against the entire A. thaliana proteome, with an e-value cut-off of 1e-5 and max_target_seqs of 1. The R package clusterProfiler was then used to identify significantly enriched GO terms (false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05)62. The resulting P-values were corrected for multiple comparisons using the method of Benjamini and Hochberg. To avoid overestimation, tandem-duplicated genes in the outlier regions were filtered before the GO enrichment analysis.

Reporting Summary

Further information on experimental design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The raw sequencing data have been deposited in the NCBI database under BioProject accession codes PRJNA358784 and PRJNA430009. The raw sequencing data have also been deposited in the BIG Data Center under BioProject accession codes PRJCA000376 and PRJCA001246. The source data underlying Figs. 1–5 are provided as a Source Data file. Data supporting the findings of this work are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files. A reporting summary for this Article is available as a Supplementary Information files. The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study and the plant materials used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Allender, C. J. & King, G. J. Origins of the amphiploid species Brassica napus L. investigated by chloroplast and nuclear molecular markers. BMC Plant Biol. 10, 54 (2010).

Snowdon, R., Lühs, W. & Friedt, W. Oilseeds Ch. 2 (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2007).

Nagaharu, U. Genome analysis in Brassica with special reference to the experimental formation of B. napus and peculiar mode of fertilization. Jpn J. Bot. 7, 389–452 (1935).

Sun, F. et al. The high-quality genome of Brassica napus cultivar ‘ZS11’ reveals the introgression history in semi-winter morphotype. Plant J. 92, 452–468 (2017).

Chalhoub, B. et al. Early allopolyploid evolution in the post-Neolithic Brassica napus oilseed genome. Science 345, 950–953 (2014).

Yang, J. et al. The genome sequence of allopolyploid Brassica juncea and analysis of differential homoeolog gene expression influencing selection. Nat. Genet. 48, 1225–1232 (2016).

Gómez-Campo, C. & Prakash, S. in Biology of Brassica Coenospecies (ed. Gómez-Campo C.) 33–58 (Elsevier, Amsterdam 1999).

Bonnema, G. in Genetics, Genomics and Breeding of Oilseed Brassicas (eds. Edwards, D., Batley, J., Parkin, I. & Kole, C.) 47–72 (CRC Press, Boca Raton 2012).

Qian, W. et al. Introgression of genomic components from Chinese Brassica rapa contributes to widening the genetic diversity in rapeseed (B. napus L.), with emphasis on the evolution of Chinese rapeseed. Theor. Appl. Genet. 113, 49–54 (2006).

Song, K. & Osborn, T. C. Polyphyletic origins of Brassica napus: new evidence based on organelle and nuclear RFLP analyses. Genome 35, 992–1001 (1992).

Song, K. M., Osborn, T. C. & Williams, P. H. Brassica taxonomy based on nuclear restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLPs). Theor. Appl. Genet. 75, 784–794 (1988).

Xu, X. et al. Resequencing 50 accessions of cultivated and wild rice yields markers for identifying agronomically important genes. Nat. Biotechnol. 30, 105–111 (2012).

Lin, T. et al. Genomic analyses provide insights into the history of tomato breeding. Nat. Genet. 46, 1220–1226 (2014).

Zhou, Z. et al. Resequencing 302 wild and cultivated accessions identifies genes related to domestication and improvement in soybean. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 408–414 (2015).

Wang, X. X. et al. The genome of the mesopolyploid crop species Brassica rapa. Nat. Genet. 43, 1035–1039 (2011).

Liu, S. et al. The Brassica oleracea genome reveals the asymmetrical evolution of polyploid genomes. Nat. Commun. 5, 1–11 (2014).

Parkin, I. A. et al. Transcriptome and methylome profiling reveals relics of genome dominance in the mesopolyploid Brassica oleracea. Genome Biol. 15, R77 (2014).

Cheng, F. et al. Subgenome parallel selection is associated with morphotype diversification and convergent crop domestication in Brassica rapa and Brassica oleracea. Nat. Genet. 48, 1–10 (2016).

Nguyen, L.-T., Schmidt, H. A., von Haeseler, A. & Minh, B. Q. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating Maximum-Likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 268–274 (2015).

Gutenkunst, R. N., Hernandez, R. D., Williamson, S. H. & Bustamante, C. D. Inferring the joint demographic history of multiple populations from multidimensional SNP frequency data. PLoS Genet. 5, e1000695 (2009).

Excoffier, L., Dupanloup, I., Huerta-Sánchez, E., Sousa, V. C. & Foll, M. Robust demographic inference from genomic and SNP data. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003905 (2013).

Terhorst, J., Kamm, J. A. & Song, Y. S. Robust and scalable inference of population history from hundreds of unphased whole genomes. Nat. Genet. 49, 303–309 (2017).

Hasan, M. et al. Association of gene-linked SSR markers to seed glucosinolate content in oilseed rape (Brassica napus ssp. napus). Theor. Appl. Genet. 116, 1035–1049 (2008).

Wang, S. B. et al. Improving power and accuracy of genome-wide association studies via a multi-locus mixed linear model methodology. Sci. Rep. 6, 19444 (2016).

Browning, B. L. & Browning, S. R. Genotype imputation with millions of reference samples. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 98, 116–126 (2016).

Qu, C. et al. Genome-wide association mapping and Identification of candidate genes for fatty acid composition in Brassica napus L. using SNP markers. BMC Genom. 18, 232 (2017).

Lu, K. et al. Genome-wide association and transcriptome analyses reveal candidate genes underlying yield-determining traits in Brassica napus. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 206 (2017).

Liu, S. et al. A genome-wide association study reveals novel elite allelic variations in seed oil content of Brassica napus. Theor. Appl. Genet. 129, 1–13 (2016).

Iuchi, S. et al. Regulation of drought tolerance by gene manipulation of 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase, a key enzyme in abscisic acid biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 27, 325–333 (2001).

Frey, A. et al. Epoxycarotenoid cleavage by NCED5 fine-tunes ABA accumulation and affects seed dormancy and drought tolerance with other NCED family members. Plant J. 70, 501–512 (2012).

Fu, Z. Q. et al. NPR3 and NPR4 are receptors for the immune signal salicylic acid in plants. Nature 486, 228–232 (2012).

Nour-Eldin, H. H. et al. NRT/PTR transporters are essential for translocation of glucosinolate defence compounds to seeds. Nature 488, 531–534 (2012).

Wu, G., Wu, Y., Xiao, L., Li, X. & Lu, C. Zero erucic acid trait of rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) results from a deletion of four base pairs in the fatty acid elongase 1 gene. Theor. Appl. Genet. 116, 491–499 (2008).

Bouché, F., Lobet, G., Tocquin, P. & Périlleux, C. FLOR-ID: an interactive database of flowering-time gene networks in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D1167–D1171 (2016).

Whittaker, C. & Dean, C. The FLC Locus: a platform for discoveries in epigenetics and adaptation changes may still occur before final publication. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 338, 1–8 (2017).

Chen, L. et al. A 2.833-kb insertion in BnFLC.A2 and its homeologous exchange with BnFLC.C2 during breeding selection generated early-flowering rapeseed. Mol. Plant 1, 222–225 (2018).

Van Lijsebettens, M. & Grasser, K. D. The role of the transcript elongation factors FACT and HUB1 in leaf growth and the induction of flowering. Plant Signal. Behav. 5, 715–717 (2010).

Bastow, R. et al. Vernalization requires epigenetic silencing of FLC by histone methylation. Nature 427, 164–167 (2004).

Wu, G.-Z. & Xue, H.-W. Arabidopsis β-ketoacyl-[acyl carrier protein] synthase I is crucial for fatty acid synthesis and plays a role in chloroplast division and embryo development. Plant Cell 22, 3726–3744 (2010).

Moreno-Pérez, A. J. et al. Reduced expression of FatA thioesterases in Arabidopsis affects the oil content and fatty acid composition of the seeds. Planta 235, 629–639 (2012).

Liu, J. et al. Natural variation in ARF18 gene simultaneously affects seed weight and silique length in polyploid rapeseed. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 5123–5132 (2015).

Gonzalez-Grandio, E. et al. BRANCHED1 promotes axillary bud dormancy in response to shade in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25, 834–850 (2013).

Zou, H.-F. et al. The transcription factor AtDOF4.2 regulates shoot branching and seed coat formation in Arabidopsis. Biochem. J. 449, 373–388 (2013).

Ignatov, A. N., Artemyeva, A. M. & Hida, K. Origin and expansion of cultivated Brassica rapa in Eurasia: linguistic facts. Acta Hortic. 867, 81–88 (2010).

Reiner, H., Holzner, W. & Ebermann, R. The development of turnip-type and oilseed-type Brassica rapa crops from the wild type in Europe-An overview of botanical, historical and linguistic facts. Proc. 9th Int. Rapeseed Congr. 4, 1066–1069 (1995).

Qi, X. et al. Genomic inferences of domestication events are corroborated by written records in Brassica rapa. Mol. Ecol. 26, 3373–3388 (2017).

Wang, M. et al. Asymmetric subgenome selection and cis-regulatory divergence during cotton domestication. Nat. Genet. 49, 579–587 (2017).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009).

McKenna, A. et al. The genome analysis toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 20, 1297–1303 (2010).

Letunic, I. & Bork, P. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v3: an online tool for the display and annotation of phylogenetic and other trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W242–W245 (2016).

Price, A. L. et al. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet. 38, 904–909 (2006).

Evanno, G., Regnaut, S. & Goudet, J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: a simulation study. Mol. Ecol. 14, 2611–2620 (2005).

Pritchard, J. K., Stephens, M. & Donnelly, P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 155, 945–959 (2000).

Purcell, S. et al. PLINK: A tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 81, 559–575 (2007).

Lancashire, P. D. et al. A uniform decimal code for growth stages of crops and weeds. Ann. Appl. Biol. 119, 561–601 (1991).

Chen, H., Patterson, N. & Reich, D. Population differentiation as a test for selective sweeps. Genome Res. 20, 393–402 (2010).

Szpiech, Z. A. & Hernandez, R. D. Selscan: an efficient multithreaded program to perform EHH-based scans for positive selection. Mol. Biol. Evol. 31, 2824–2827 (2014).

Browning, B. L. & Browning, S. R. Genotype imputation with millions of reference samples. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 98, 116–126 (2016).

Dobin, A. et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21 (2013).

Trapnell, C. et al. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with topHat and cufflinks. Nat. Protoc. 7, 562–578 (2013).

Yu, G., Wang, L.-G., Han, Y. & He, Q.-Y. clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS 16, 284–287 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor William Lucas for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31830067, U1302266, 31571701, and 31871653), the 973 Project (2015CB150201), the National Key Research and Development Plan (2018YFD0100501 and 2016YFD0101007), the 111 Project (B12006), the Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing (cstc2018jcyjA1219).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L., X.W., and A.H.P. designed and supervised the study; K.L., X.L., L.W. and J.W. collected the samples and performed the phenotyping; M.L., C.Z., Z.C., Z.X., H.J., K.Z., H.D. and C.Q. measured the agronomic traits; K.L. and L.W. led the data analysis with contributions from W.Q., L.L., R.W., Q.Z., J.Y., Y.F., W.S. and X.X. and Y.W., F.C., X.C., J.M., Y.L., Y.-R. C., Y.H., Z.T., H.W., Y.N., N.-N.L., G.Z., H.Z. and N.L. contributed to the data collection and interpretation of results, and K.L., X.W., A.H.P. and J.L. drafted the paper. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Journal peer review information: Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, K., Wei, L., Li, X. et al. Whole-genome resequencing reveals Brassica napus origin and genetic loci involved in its improvement. Nat Commun 10, 1154 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09134-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09134-9

This article is cited by

-

Asymmetric and parallel subgenome selection co-shape common carp domestication

BMC Biology (2024)

-

The functional divergence of homologous GPAT9 genes contributes to the erucic acid content of Brassica napus seeds

BMC Plant Biology (2024)

-

Macroevolutionary dynamics of gene family gain and loss along multicellular eukaryotic lineages

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Natural variation in BnaA9.NF-YA7 contributes to drought tolerance in Brassica napus L

Nature Communications (2024)

-

A genomic variation map provides insights into peanut diversity in China and associations with 28 agronomic traits

Nature Genetics (2024)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.