Abstract

By taking advantage of large changes in geometric and electronic structure during the reversible trans–cis isomerisation, azobenzene derivatives have been widely studied for potential applications in information processing and digital storage devices. Here we report an unusual discovery of unambiguous conductance switching upon light and electric field-induced isomerisation of azobenzene in a robust single-molecule electronic device for the first time. Both experimental and theoretical data consistently demonstrate that the azobenzene sidegroup serves as a viable chemical gate controlled by electric field, which efficiently modulates the energy difference of trans and cis forms as well as the energy barrier of isomerisation. In conjunction with photoinduced switching at low biases, these results afford a chemically-gateable, fully-reversible, two-mode, single-molecule transistor, offering a fresh perspective for creating future multifunctional single-molecule optoelectronic devices in a practical way.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the initial proposal of molecular electronics in the 1970s, single-molecule devices have been regarded as a promising solution to reach the ultimate limit of device miniaturisation1. To this end, researchers from interdisciplinary backgrounds have paid considerable efforts in studying the charge transport behaviours through molecular junctions2. To date, various functionalities have been achieved2,3, which include switching4,5, rectification6,7,8, electrical field gating9,10, mechanical force gating11,12,13,14, thermoelectric energy conversion15,16,17, electroluminescence18, and magnetoresistance19,20. In addition to device functionalisation, single-molecule devices also provide a unique platform to explore the intrinsic properties of materials at the atomic/molecular level and reveal novel quantum phenomena that are inaccessible in bulky materials21. Among discrete functional devices, controllable electrical transistors are particularly attractive because they are the basic component in electrical circuits, and have been widely studied in the field of molecular electronics22. In general, there are several mechanisms to realise a reversible transition between two conductance states23: conformational changes (usually stimulated by light, ion, and junction elongation/compression4,13,14), valence-state changes controlled by an electrochemical potential24, and spin-state changes often based on spin-crossover compounds19,25,26. In most cases, changes occur in the molecular backbone through which carriers are transported. It is worth mentioning that atoms or groups at the sidegroup position, which have even no continuous σ-bond with the junction, have been demonstrated to have significant effects on the electronic or geometric properties of the molecular backbones, as well as the conductance behaviours27,28,29, forming the basis for creating functional molecular devices.

Azobenzene derivatives are typically photochromic materials, which are able to isomerise back-and-forth between two states (cis/trans) under irradiation of different wavelengths of light (UV/visible). This process can result in two significant changes in either the structure or the polarity of the azobenzene unit. One is that the trans conformation is near planar, while the cis isomer adopts a bent conformation with its phenyl rings twisted ~55° out of the plane from the azo group. The other is that the polarity change depends on the substituents on the two phenyl rings. In addition, the two isomers differentiate in the end-to-end distance30—the distance between the two carbon atoms in position 4 of the phenyl rings is ~9.0 and ~5.5 Å in trans form and cis form, respectively. These properties make azobenzene units popular in many systems, such as polymers31, liquid crystals32, and nanoparticles33, which have produced various novel applications including digital storage34 and on-command drug delivery35. At the molecular level, in addition to external light stimuli, previous reports based on scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) suggested that resonant or inelastic tunneling of electrons36,37 or the electric field38 could induce the isomerisation of azobenzene.

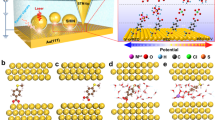

In the present work, we demonstrate a chemically-gated, fully-reversible, two-mode, single-molecule transistor based on a robust graphene-molecule-graphene single-molecule junction (GMG-SMJ) formed by covalently sandwiching an azobenzene unit, which is immobilised at the side position of a terphenyl aromatic chain, between graphene point contacts (Fig. 1a). One mode is asymmetric stochastic conductance switching due to electric field-induced isomerisation of azobenzene and the other is reversible photoswitching at low biases. Note that this azobenzene single-molecule transistor, which is switched between an ON and OFF state because the two isomers have the different resistances, is different from common single-molecule transistors in which the source-drain currents can be continuously tuned by using the gate voltage9,39. A crucial discovery is that both quantum mechanical calculations and experimental data reveal that an electric field can unambiguously modulate the energy difference between trans and cis forms, as well as the energy barrier of conformational changes. Since the effectiveness of an electric field on trans and cis is different, either of the two conformations can be tuned as the stable state, which is the first study in single-molecule electrical circuits.

Device structure and dipole analysis of TTDA. a Schematic representation of the device structure that highlights a reversible isomerisation of the azobenzene unit between trans and cis forms triggered by either optical or electrical stimuli. The azobenzene sidegroup serves as a chemical gate to modulate the conductance of the molecular backbone. b Dipole projection on the molecular backbone (the actual charge transport pathway). The arrow denotes the direction of the dipole projection

Results

Design and device fabrication

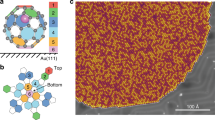

The synthesis of 2′-p-tolyldiazenyl-1,1′:4,4′-terphenyl-4,4″-dicarboxylic acid (TTDA, Fig. 1b) was done according to a previous report40. Then, by using nanogapped graphene point contacts fabricated through a dash-line lithographic (DLL) method described elsewhere41, we covalently incorporated individual TTDA molecules into graphene electrodes that have been prefunctionalised by p-phenylenediamine through amide bonds to form single-molecule junctions (Fig. 1, Supplementary Figures 1–3). Due to the covalent bond at the electrode–molecule contact interface and the good compatibility between graphene electrodes and molecules, these reconnected single-molecule junctions are stable, ensuring the following investigation of the stimuli-responsive conductance behaviours of the azobenzene unit.

As mentioned before, trans and cis forms of the azobenzene unit have distinct effects on the electronic structure of the whole molecule. In the current case, we chose a conjugated aromatic chain containing an azobenzene sidegroup as the molecular bridge because the isomerisation of azobenzene incorporated through side substitution does not essentially alter the geometric structure of the charge transport pathway, although there is a large geometric change of the azobenzene unit. In comparison with the cases where isomerisation groups are placed in the backbone, the present design avoids the possible instability of molecular junctions resulting from the length change during isomerisation. This point is of crucial importance to achieve stable and reversible switching effects, and makes it more suitable to analyse the origin of the conductance differences between trans and cis forms on the basis of our previous unreported systematic exploration. Furthermore, we used the Gaussian package to investigate the electronic structure of these two isomers. As shown in Fig. 1b, the two forms of azobenzene show different dipole moments projecting an opposite direction along the terphenyl backbone (~1.22D and ~6.59D for trans and cis forms, respectively), revealing a significant asymmetry of the conformations. This different asymmetry between trans and cis forms is still preserved in our device system (Supplementary Figure 6). Previous reports have demonstrated that an electric field could act on asymmetry molecules, thus changing the conformation42,43. This strongly implies that other than the constant energy difference at the ground state, electric field could be utilised to tune the energy alignment of trans and cis forms as well as the transition energy barrier, resulting in an isomerisation of the substituted azobenzene unit in a single-molecule electrical circuit.

Voltage-dependent stochastic switching

On the basis of the investigation of current–voltage (I–V) characteristics of TTDA-based single-molecule junctions in the dark, asymmetric stochastic switching between two distinct conductance states were observed mainly at bias voltages in the range of −0.05 to −0.20 V, as represented in Fig. 2 out of 7 working devices. The I–V characteristics over the temperatures ranging from 115 to 250 K revealed that the switching rate between these two states is accelerated by increasing the temperature. We note that this voltage-dependent switching behaviour is obviously distinguishable from stochastic switching induced by the conformational change of the hexaphenyl aromatic chain previously reported (different dihedral angles between the outer two benzene rings)44. The asymmetrical voltage-dependence and small threshold voltage values suggest that the charge-trap mechanism cannot explain the present stochastic switching phenomenon45.

To investigate such voltage dependence in detail, we performed real-time current measurements at different bias voltages ranging from −0.05 to −0.30 V in the dark and under vacuum. The obtained current–time (I–t) curves and the corresponding conductance-based histograms at 160 K are shown in Fig. 3. It is clear that with increasing the negative voltages from −0.05 to −0.30 V, the proportion of the high conductance state grew markedly, whereas the proportion of the low conductance state gradually decreased to zero. On the basis of I–t data, the on/off ratios of the conductance switching were calculated to be in the range from ~2.00 to ~2.46, showing little dependence on bias voltages (Supplementary Table 1). To rule out potential artifacts, we also investigated the conductance behaviour of a control molecule—a pure terphenyl aromatic chain without any substituted azobenzene sidegroup (Supplementary Figures 4, 5). There existed only one single conductance state. We did not observe the same stochastic switching at similar temperatures (Supplementary Figure 11) and bias voltages (Supplementary Figure 12). Collectively, we believe that the stochastic switching effect in the azobenzene–terphenyl aromatic chain originates from the azobenzene unit, other than the terphenyl unit due to δ-bond-rotation-induced stereoelectronics44.

Voltage dependence of stochastic switching. a–e I–t curves, corresponding enlarge I–t curves marked in blue, and corresponding histograms of a working GMG-SMJ device measured at different bias voltages: −0.05 V (a), −0.10 V (b), −0.15 V (c), −0.20 V (d), and −0.30 V (e) at 160 K. Insets in the right column are the enlarged curves marked in yellow. The gate voltage is 0 V

Photoswitching effect at low bias voltages

We attributed the two conductance states to corresponding molecular conformations by further revealing the photoresponsive behaviour of the azobenzene unit. As shown in Fig. 4, the device reversibly switched its conductance between a high state and a low state with an on/off ratio of ~2.1 under sequential ultraviolet (UV) and visible light irradiations, where a very small positive voltage of 0.01 V was adopted to prevent the effect of electric field. The similar on/off ratio with stochastic switching in Fig. 3 suggests the same isomerisation process. Control experiments by using a device reconnected by a terphenyl aromatic molecule without the substituted azobenzene sidegroup (Supplementary Figure 4) did not show similar photoswitching behaviours (Supplementary Figure 13), thus proving that the photoswitching effect as well as electric field-induced stochastic switching should originate from reversible trans–cis isomerisation of azobenzene. The large current fluctuation under UV irradiation might be due to the photoinduced instability of cis azobenzene or some other unknown stereoelectronic effect, which deserves further studies in the future.

Photoswitching behaviours. At low bias voltages, real-time measurements reveal reversible switching between cis and trans forms of TTDA upon exposure to UV and visible light irradiations, respectively. The right panel is the corresponding statistic histogram, showing that the conductance of cis form is higher than that of trans form. The source-drain voltage is 0.01 V; the gate voltage is 0 V

Discussion

To reveal how the different isomers of azobenzene affect the conductance behaviour of the terphenyl aromatic chain, we analysed the equilibrium transmission spectra of both trans and cis GMG-SMJs by using density functional theory (DFT)-based nonequilibrium Green’s function (NEGF) approach. As shown in Fig. 5a, in comparison with the trans form, the perturbed frontier molecular orbitals (p-FMOs) of the cis form shift positively in the energy window. This is because the cis possesses poorer conjugation within the side azobenzene structure than the trans (see also the scattering state analysis in Supplementary Figure 7). Based on the Landauer–Büttiker formalism of quantum transport, the energy gap between p-FMOs and the Fermi level of the electrodes plays a crucial role in the current under a low bias voltage: the smaller the gap is, the more electrons can enter the Fermi window in the bias range explored. As the perturbed highest occupied molecular orbital (p-HOMO) is much closer to the graphene Fermi level than the perturbed lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (p-LUMO), p-HOMO provides the dominant contribution to the conductance at small bias voltages. When the azobenzene changes from trans to cis, p-HOMO moves towards the graphene Fermi level (~0.07 eV), thus leading to larger transmission around the Fermi level and higher conductance at small bias voltages. Therefore, we theoretically attributed low and high conductance states to trans and cis forms, respectively, which is consistent with the experimentally-observed photoswitching effect in Fig. 4. It should be mentioned that there is a discrepancy between the observed conductances and the predicted transmission.

Mechanism of voltage-dependent conductance switching. a Transmission spectra of a GMG-SMJ with trans (orange) and cis (green) isomers, respectively. b Voltage-dependent thermodynamic isomerisation energy parameters deduced from experimental data. c Voltage-dependent isomerisation energy diagram, which is calculated from the theoretical simulations. d, e Schematic of relative electric potential energies of trans and cis forms under positive and negative bias electric fields, respectively. The voltage drops of trans and cis systems were approximately treated as the same linear tendency Vx for a simple sketch demonstration

Next, we investigated the experimentally observed process of switching from low to high conductance states by increasing the voltage from −0.05 to −0.30 V in the dark (Fig. 3). We shall reach the conclusion that applying negative voltages can isomerise azobenzene from trans to cis gradually.

Given the fact that the proportions of trans and cis forms can be tuned directly by the voltage in the dark, a modulated thermodynamic isomerisation energy is ΔG = −RTln([H]/[L]), where [H] and [L] are the occurrence proportions of cis and trans forms, respectively (Supplementary Table 2). As shown in Fig. 5b, −ln([H]/[L]) changes linearly with bias voltages and decreased to zero when negative voltages increased to −0.13 V. This implies a changed energy landscape between trans and cis under the electric field. To confirm the intrinsic mechanism of this asymmetric voltage-dependent trans–cis isomerisation, we performed first-principles calculations on the energy evolution of trans and cis forms of azobenzene in the GMG-SMJ system. We globally define the isomerisation energy as the energy difference between cis and trans forms: ΔE = Ec−Et, where the superscript c and t denote cis and trans, respectively. In a biased two-probe system, ΔE is determined by two factors: one is the intrinsic isomerisation energy in the absence of voltages, \(\Delta E_0 = E_0^c - E_0^t\); and the other is the voltage-induced electrostatic energy difference defined as Δε = εc − εt. The intrinsic isomerisation energy is around 70 kJ mol−1 (the energy value at zero bias as shown in Fig. 5c), resulting in a favourable state of trans at the equilibrium condition. The voltage-induced electrostatic energy difference Δε of the two-probe junction under different biases were calculated by the DFT–NEGF technique and obtained by the formula: \(\Delta \varepsilon = - \left| {\mathrm{e}} \right|{\int} {\left[ {\rho _c\left( r \right)V_c\left( r \right) - \rho _t\left( r \right)V_t\left( r \right)} \right]} {\mathrm{d}}r\), where e is the electron charge, ρ(r) and V(r) are the self-consistently-calculated electron density distribution and electric potential distributions induced by the bias electric field at the molecular device region. Indices c and t denote cis and trans conformation systems, respectively. The calculated function between Δε and voltages was shown in Supplementary Figure 8, where the Δε value is found to be linearly dependent on the bias voltages. We combined the bias-dependent Δε with the zero-bias ΔE0 to obtain the total under-bias isomerisation energy ΔE, and the energy diagram was shown in Fig. 5c. With the help of a negative voltage, the isomerisation energy from trans to cis decreased linearly and reached the critical transition point (ΔE = 0) at −0.21 V, since Δε can totally offset the intrinsic molecular energy difference under this bias condition. When the bias goes more negative, cis is the more stable state than trans (ΔE < 0), according to the energy diagram in Fig. 5c. In contrast, at the positive voltage direction, the energy difference between cis and trans forms maintains the rising trend along with the voltage, resulting in a continued stable state of trans. Both the transition voltage and linear changing tendency are qualitatively consistent with experimental data of the thermodynamic energy term −ln([H]/[L]) in Fig. 5b. On account of the fixed spatial position of the backbone, the main electron density difference of the trans and cis structures results from the azobenzene free phenyl ring (side group marked by the orange and green circles, respectively), which dominates Δε under biases as shown in the schematic demonstrations of Fig. 5d, e. In addition, this physical picture revealed that structural asymmetries of trans and cis play the key role in the response to the applied bias. Considering the randomness of the molecular-device fabrication, it can be inferred that an opposite-orientation-aligned molecule should have the opposite polarity of the bias response: the positive bias deceased the energy difference and the transition point appeared at the positive bias region. This inference was confirmed by six other devices as shown in Supplementary Figure 9, demonstrating the robustness and reproducibility. Collectively, both experimental and theoretical analyses consistently establish the physical picture that in the two-probe junction, the mechanism of stochastic switching is the capability of an externally applied electric field to adjust the molecular energies of trans and cis forms that determine the most stable state. It is the different forms of azobenzene (either trans or cis) that serve as an efficient chemical gate (because of their different dipole moments as discussed before) to tune charge transport of the molecular main chain.

We further investigate the dynamic process of activating the molecule to overcome the energy barrier between cis and trans forms. On the basis of Figs. 2 and 3, we observed two facts. One is that the stochastic jumping occurs immediately as long as a small negative voltage is applied. The other is that the isomerisation rate gradually increases with increasing the voltages. To unravel the kinetics of azobenzene isomerisation induced by electric field, the I–t curves were idealised based on the hidden-Markov-model simulation by using a QUB software (Supplementary Figure 10), from which the time intervals of trans and cis forms (Ttrans and Tcis) can be obtained. Plots of the dwell times of each form obtained by frequency analysis for a typical signal at a bias of −0.20 V are shown in Fig. 6a, b. Both plots fit a single-exponential function with time constants corresponding to the average lifetimes (τtrans and τcis) of trans and cis forms. The average lifetimes of trans and cis forms at 160 K under different bias voltages were obtained as listed in Supplementary Table 2. With increasing the negative voltage, τtrans decreases from ~842.37 to ~8.50 ms, while τcis increases from ~24.13 to ~95.11 ms. Accordingly, the rates of isomerisation kt→c = 1/τtrans (from trans to cis) and kc→t = 1/τcis (from cis to trans) have the opposite changing tendency. For the isomerisation rate, there exists an expression as \(- {\mathrm{ln}}k \propto E_{\mathrm{a}} {/} RT\), where Ea is the activation energy (a free energy difference between the stable state and the transition state). Here, we can define \(E_{\mathrm{a}}^{t \to c} = E_{\mathrm{a},0}^{t \to c} + \varepsilon _{\mathrm{a}}^{t \to c} = E_{\mathrm{a},0}^{t \to c} + \left( {\varepsilon ^{\mathrm{T}} - \varepsilon ^{t}} \right)\) and \(E_{\mathrm{a}}^{c \to t} = E_{\mathrm{a},0}^{c \to t} + \varepsilon _{\mathrm{a}}^{c \to t} = E_{\mathrm{a},0}^{c \to t} + \left( {\varepsilon ^{\mathrm{T}} - \varepsilon ^c} \right)\), where the superscript T denotes the transition state during the isomerisation process and Ea,0 is the intrinsic activation energy barrier without the bias field effect. In this way, εT − εt and εT − εc determine how \(E_{\mathrm{a}}^{t \to c}\) and \(E_{\mathrm{a}}^{c \to t}\) change upon the application of the bias voltage, respectively. As shown in Fig. 6c, both −lnkt→c and −lnkc→t depend linearly on the negative voltage but with an opposite changing trend and the different slopes in the numeric value. Therefore, with increasing the negative voltage, εT − εt decreases and εT − εc increases, which means that the additional energy of the transition state caused by electric field is between those of trans and cis forms. This is also consistent with the model shown in Fig. 5d, e as the position of the azobenzene sidegroup in the transition state is between those of trans and cis forms. Figure 6d qualitatively shows the schematic voltage-dependent energy diagram of the molecules in trans, cis, and transition states, where the energy of the trans form is set as the reference. We can infer that the appearance of stochastic jumping is a result of the tunable activation energy motivated by thermal or inelastic tunneling of electrons, or their cooperative effect. It is worth mentioning that at a small voltage of 0.01 V, the structure of azobenzene can be stabilised (either cis and trans) for long-term measurements as demonstrated in Supplementary Figure 14, thus producing a resettable single-molecule memoriser.

Relationship between the activation energy and the bias voltage. a, b Statistics histograms of the dwell times at trans (a) and cis (b) states fitted by a single-exponential function. c Activation energy parameters of trans–cis (orange) and cis–trans (green) as a function of the bias voltage. The variation of cis–trans is less than trans–cis. d Schematic of the energy alignment among trans, cis, and transition states triggered by the bias voltage. We take the energy of trans as the reference

This work demonstrated a new phenomenon of asymmetric stochastic conductance switching via efficient side-group chemical gating in a GMG-SMJ-based electrical circuit. The key to the success in realising such a switching effect is the efficient adjustment of the energy alignments among trans, cis, and transition states by an external electric field, which plays a crucial role in the trans–cis isomerisation process, due to the asymmetric spatial orientation of the azobenzene unit. In combination with the photoswitching phenomenon, these devices behave as a chemically-gated, fully-reversible, two-mode, single-molecule molecular circuit, thus providing new insights into constructing future practical single-molecule devices and logic gates.

Methods

Device fabrication and molecular connection

High-quality single-layer graphene grown through a chemical vapor deposition (CVD) process was first transferred to the silicon wafer with a 300 nm silicon oxide layer. Then the source/drain metal electrode arrays (8 nm Cr/60 nm Au) were patterned by photolithography and thermal evaporation. The devices with carboxylic acid-terminated nanogapped graphene point contacts (the top panel in Supplementary Figures 2 and 4) were fabricated by a DLL method described in detail elsewhere41. Individual TTDA molecules were connected to graphene point contacts by a dehydration reaction in two steps (Supplementary Figures 2 and 4). In brief, in the first step, p-phenylenediamine was dissolved in anhydrous pyridine with the concentration of about 10−3 M. Then, the freshly-cut graphene devices and 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDCI), a well-known carbodiimide dehydrating/activating agent, were added to the solution for connection. After 2 days in the dark and argon atmosphere, the devices were taken out from the solution, cleaned sequentially by ultrapure water and acetone, and dried by nitrogen gas. In the second step, the resulted devices and EDCI were added to the solution of TTDA with the concentration of 10−4 M. After 2 days in the dark and argon atmosphere, the devices were taken out from the solution, cleaned sequentially by ultrapure water and acetone, and finally dried by nitrogen gas. In this work, TTDA was synthesised by following the reported procedure40, and the controlled molecule (4-[4-(4-carboxyphenyl)phenyl]benzoic acid) was purchased from Accela Chem Bio Co. Ltd. and used without further purification.

Electrical characterisation

Device characterisations were carried out by utilising an Agilent 4155C semiconductor characterisation system and a ST-500-Probe station (Janis Research Company) with a liquid nitrogen cooling system. For I–V measurements, the scanning interval is 0.6 mV per step. For I–t measurements, the integration time is 5 ms per step. UV irradiation (λ = 365 nm) was carried out with a handheld lamp (CU6, NITECORE). The visible light was obtained from a polychromatic light with a UV light filter (420 nm cut-off wavelength).

Theoretical calculation

The structural relaxation of the isolated molecules and two-probe transport junctions, the molecular dipole, and the intrinsic molecular energy calculation were carried out by the DFT in the Gaussian package46. The B3LYP hybrid functional and the 6-31G basis set were taken in the Gaussian calculation. The electric potential energy under finite biases and the charge transport properties of the two-probe structures were obtained by carrying out the DFT within the NEGF formalism, as implemented in the quantum transport package Nanodcal47,48. Double-zeta polarised atomic orbital basis set was used in the NEGF–DFT calculation, and exchange-correlation was treated at the PBE-GGA level. The cutoff energy for the real-space grid was set at 1360 eV. The NEGF–DFT self-consistent calculations were deemed converged when every element of the Hamiltonian matrix and the density matrix were converged to less than 10−4 a.u, and the total energy was converged to less than 10−5 a.u. In the transmission spectra (Fig. 5a), the Fermi level of the graphene electrode (Ef) has been shifted −0.5 eV to simulate the experimental fact that our graphene electrode is p-doped due to the wet transfer procedure. The transmission spectra and scattering states were calculated by the Green’s function and scattering matrix methods (Supplementary Figure 7). As shown in Supplementary Figure 7, p-HOMO and p-LUMO are contributed from the orbitals around the branch chain. The trans form has a better conjugated structure around the branch chain than the cis form, leading to lower p-FMOs energies.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Aviram, A. & Ratner, M. A. Molecular rectifiers. Chem. Phys. Lett. 29, 277–283 (1974).

Xiang, D., Wang, X., Jia, C., Lee, T. & Guo, X. Molecular-scale electronics: from concept to function. Chem. Rev. 116, 4318–4440 (2016).

Xin, N. & Guo, X. Catalyst: the renaissance of molecular electronics. Chem 3, 373–376 (2017).

Jia, C. et al. Covalently bonded single-molecule junctions with stable and reversible photoswitched conductivity. Science 352, 1443–1445 (2016).

Zhang, J. L. et al. Towards single molecule switches. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 2998–3022 (2015).

Atesci, H. et al. Humidity-controlled rectification switching in ruthenium-complex molecular junctions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 117–121 (2018).

Díez-Pérez, I. et al. Rectification and stability of a single molecular diode with controlled orientation. Nat. Chem. 1, 635–641 (2009).

Capozzi, B. et al. Single-molecule diodes with high rectification ratios through environmental control. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 522–527 (2015).

Perrin, M. L., Burzuri, E. & van der Zant, H. S. J. Single-molecule transistors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 902–919 (2015).

Song, H. et al. Observation of molecular orbital gating. Nature 462, 1039–1043 (2009).

Bruot, C., Hihath, J. & Tao, N. Mechanically controlled molecular orbital alignment in single molecule junctions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 35–40 (2012).

Perrin, M. L. et al. Large tunable image-charge effects in single-molecule junctions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 282–287 (2013).

Quek, S. Y. et al. Mechanically controlled binary conductance switching of a single-molecule junction. Nat. Nanotechnol. 4, 230–234 (2009).

Su, T. A., Li, H., Steigerwald, M. L., Venkataraman, L. & Nuckolls, C. Stereoelectronic switching in single-molecule junctions. Nat. Chem. 7, 215–220 (2015).

Kim, Y., Jeong, W., Kim, K., Lee, W. & Reddy, P. Electrostatic control of thermoelectricity in molecular junctions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 881–885 (2014).

Reddy, P., Jang, S. Y., Segalman, R. A. & Majumdar, A. Thermoelectricity in molecular junctions. Science 315, 1568–1571 (2007).

Lee, W. et al. Heat dissipation in atomic-scale junctions. Nature 498, 209–212 (2013).

Reecht, G. et al. Electroluminescence of a polythiophene molecular wire suspended between a metallic surface and the tip of a scanning tunneling microscope. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 047403 (2014).

Thiele, S. et al. Electrically driven nuclear spin resonance in single-molecule magnets. Science 344, 1135–1138 (2014).

Natterer, F. D. et al. Reading and writing single-atom magnets. Nature 543, 226–228 (2017).

Aradhya, S. V. & Venkataraman, L. Single-molecule junctions beyond electronic transport. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 399–410 (2013).

Chen, L. et al. Towards single-molecule optoelectronic devices. Sci. China Chem. 61, 1368–1384 (2018).

Liu, Z., Ren, S. & Guo, X. Switching effects in molecular electronic devices. Top. Curr. Chem. 375, 56 (2017).

Yin, X. et al. A reversible single-molecule switch based on activated antiaromaticity. Sci. Adv. 3, eaao2615 (2017).

Harzmann, G. D., Frisenda, R., van der Zant, H. S. J. & Mayor, M. Single-molecule spin switch based on voltage-triggered distortion of the coordination sphere. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 13425–13430 (2015).

Sanvito, S. Molecular spintronics. Chem. Soc. Rev. 40, 3336–3355 (2011).

Venkataraman, L. et al. Electronics and chemistry: varying single-molecule junction conductance using chemical substituents. Nano Lett. 7, 502–506 (2007).

Lo, W. Y., Bi, W., Li, L., Jung, I. H. & Yu, L. Edge-on gating effect in molecular wires. Nano Lett. 15, 958–962 (2015).

Ismael, A. K. et al. Side-group-mediated mechanical conductance switching in molecular junctions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 15378–15382 (2017).

Zhou, H. X. Effect of catenation on protein folding stability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 9280–9281 (2003).

Iamsaard, S. et al. Conversion of light into macroscopic helical motion. Nat. Chem. 6, 229–235 (2014).

Soberats, B. et al. Macroscopic photocontrol of ion-transporting pathways of a nanostructured imidazolium-based photoresponsive liquid crystal. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 9552–9555 (2014).

Zhao, H. et al. Reversible trapping and raction acceleration within dynamically self-assembling nanoflasks. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 82–88 (2015).

Hu, Z., Deibert, B. J. & Li, J. Luminescent metal–organic frameworks for chemical sensing and explosive detection. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 5815–5840 (2014).

Horcajada, P. et al. Metal–organic frameworks in biomedicine. Chem. Rev. 112, 1232–1268 (2012).

Safiei, A., Henzl, J. & Morgenstern, K. Isomerization of an azobenzene derivative on a thin insulating layer by inelastically tunneling electrons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 216102 (2010).

Choi, B. Y. et al. Conformational molecular switch of the azobenzene molecule: a scanning tunneling microscopy study. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 156106 (2006).

Alemani, M. et al. Electric field-induced isomerization of azobenzene by STM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 14446–14447 (2006).

Xin, N. et al. Tuning charge transport in aromatic-ring single-molecule junctions via ionic-liquid gating. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 130, 14222–14227 (2018).

Meng, X., Gui, B., Yuan, D., Zeller, M. & Wang, C. Mechanized azobenzene-functionalized zirconium metal–organic framework for on-command cargo release. Sci. Adv. 2, e1600480 (2016).

Cao, Y. et al. Building high-throughput molecular junctions using indented graphene point contacts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 12238–12232 (2012).

Henningsen, N., Rurali, R., Franke, K. J., Fernández-Torrente, I. & Pascual, J. I. Trans to cis isomerization of an azobenzene derivative on a Cu(100) surface. Appl. Phys. A 93, 241–246 (2008).

Qiu, X. H., Nazin, G. V. & Ho, W. Mechanisms of reversible conformational transitions in a single molecule. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 196806 (2004).

Xin, N. et al. Stereoelectronic effect-induced conductance switching in aromatic chain single-molecule junctions. Nano Lett. 17, 856–861 (2017).

Schwarz, F. et al. Field-induced conductance switching by charge-state alternation in organometallic single-molecule junctions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 170–176 (2015).

Frisch, M. J. Revision C.02. (Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford, CT, 2004).

Taylor, J., Guo, H. & Wang, J. Ab initio modeling of quantum transport properties of molecular electronic devices. Phys. Rev. B 63, 245407 (2001).

Gu, C. et al. Label-free dynamic detection of single-molecule nucleophilic substitution reactions. Nano Lett. 18, 4156–4161 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge primary financial supports from National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFA0204901 and 2016YFA0300902), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 21727806, 11774396 and 11474328), the Natural Science Foundation of Beijing (Z181100004418003), the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (H.G.), and the Interdisciplinary Medicine Seed Fund of Peking University. The authors thank the CalcuQuebec and Compute Canada for computation facilities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.G., S.M. and H.G. conceived and designed the experiments. L.M. and N.X. fabricated the devices. L.M., N.X., C.S. and G.Z. performed the device measurements. B.G., J.S. and C.W. carried out the molecular synthesis. C.H. and H.G. built and analysed the theoretical bias-induced isomerisation model and performed the quantum transport calculation. C.H. and J.W. performed the isolated molecule calculation. X.G., H.G., S.M., L.M., N.X. and C.H. analysed the data and wrote the paper. All the authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Journal peer review information: Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Meng, L., Xin, N., Hu, C. et al. Side-group chemical gating via reversible optical and electric control in a single molecule transistor. Nat Commun 10, 1450 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09120-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09120-1

This article is cited by

-

On–off conduction photoswitching in modelled spiropyran-based metal-organic frameworks

Communications Chemistry (2023)

-

Graphene–molecule–graphene single-molecule junctions to detect electronic reactions at the molecular scale

Nature Protocols (2023)

-

Non-covalent interaction-based molecular electronics with graphene electrodes

Nano Research (2023)

-

Reactions in single-molecule junctions

Nature Reviews Materials (2022)

-

Investigation of electronic excited states in single-molecule junctions

Nano Research (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.