Abstract

Geometric or electronic confinement of guests inside nanoporous hosts promises to deliver unusual catalytic or opto-electronic functionality from existing materials but is challenging to obtain particularly using metastable hosts, such as metal–organic frameworks (MOFs). Reagents (e.g. precursor) may be too large for impregnation and synthesis conditions may also destroy the hosts. Here we use thermodynamic Pourbaix diagrams (favorable redox and pH conditions) to describe a general method for metal-compound guest synthesis by rationally selecting reaction agents and conditions. Specifically we demonstrate a MOF-confined RuO2 catalyst (RuO2@MOF-808-P) with exceptionally high catalytic CO oxidation below 150 °C as compared to the conventionally made SiO2-supported RuO2 (RuO2/SiO2). This can be caused by weaker interactions between CO/O and the MOF-encapsulated RuO2 surface thus avoiding adsorption-induced catalytic surface passivation. We further describe applications of the Pourbaix-enabled guest synthesis (PEGS) strategy with tutorial examples for the general synthesis of arbitrary guests (e.g. metals, oxides, hydroxides, sulfides).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Loading guests (e.g., molecules, clusters or particles) inside the pre-existing pores of nanoporous hosts (guest@nanoporous-host) is one of the key post-synthesis modification strategies for porous materials1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. It can yield highly active and stable heterogeneous catalysts2,3,4,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17 as well as robust photo/electro-luminescence materials2,5,6,18 with tunable band structures in quantum confinement. Forming guests within the pores has been extensively explored using inorganic nanoporous materials1,2,10 and supramolecular cages5,11 (i.e., host–guest chemistry and/or inclusion chemistry). Besides metal particles/clusters4,13,14,16,19, however, such synthesis is still challenging or impossible for other types of guest particles/clusters (e.g., oxides, hydroxides, sulfides, nitrides, phosphides) inside the host’s cavity/channel. Many hosts have very small aperture (a.k.a. window) opening sizes (typically <2 nm), and hence direct impregnation of guest compounds with much larger sizes is no longer feasible. Guests, therefore, have to be assembled locally within the cavity/channel (i.e., ship-in-a-bottle assembly9,14,20). The general ‘ship-in-a-bottle’ approach is to load smaller precursors (e.g., salts and organometallics) into pre-formed porous host materials via solution-based, gas-phase or mechanical-mixing impregnation, followed by either thermal/photochemical decomposition or redox reaction (with either strong redox reagents, e.g., hydrazine and NaBH4, or high-temperature treatment in reducing atmosphere, e.g., H2)2,4. These methods which are useful for bulk or nanostructure synthesis (i.e., unconfined systems) often fail to work properly in nanoporous hosts. The major dilemmas are that (i) many of the reactants are still too large to be impregnated and (ii) the conditions required to form a target guest may damage or destroy the host structure4. Nonetheless, the ship-in-a-bottle strategy has been recently recognized as a promising way to post-synthetically functionalize porous metal–organic frameworks (MOFs)3,4,11,12,13,14,15,16,17, which are host matrices assembled with metal centers and organic ligands with extremely diverse chemistries, topologies and pore architectures21,22,23,24,25,26. By immobilizing the guests inside MOFs, guest aggregation/fusion can be effectively prevented4,19. Meanwhile, MOF hosts have been found to influence the properties of the guests, e.g., modulation of electron–hole recombination rates for quantum dots4. Hence, there is a demand to carry out ship-in-a-bottle synthesis with sufficiently small reaction reagents under mild conditions, as many of these metastable MOFs suffer from poor chemical and thermal stability2,4,22,23,24,25. A rational route for incorporation of guest compounds into an arbitrary nanoporous host should enable the investigation of multiple host–guest systems with surprising functionalities.

We realize that the synthetic conditions of guests can be pre-determinable based on pH/potential-dependent equilibrium solid/solution maps27,28,29,30,31 (well known by materials scientists as Pourbaix diagrams, e.g., Fig. 1a), which have been extensively investigated and used for depicting relevant thermodynamics during a corrosion process (normally solid → solution)32. Instead of studying solid → solution reactions, we use the Pourbaix diagrams to select precursor solutions and synthetic conditions (i.e., redox potential and/or pH) to solidify the desired guests (i.e., solution → solid processes) within the pores of the hosts30. We term this strategy Pourbaix enabled guest synthesis (PEGS) (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Section 1). Briefly, by checking the Pourbaix diagrams we can find the difference in the redox potential (ΔE) and/or pH between a soluble guest precursor and a desired guest. We can then shortlist the hosts and reagents (e.g., precursors) that meet the guest formation requirements and select the most appropriate candidates perhaps with other properties (i.e., desired boiling temperature and hydrophobicity) to manage the ship-in-a-bottle synthesis.

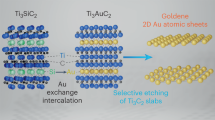

Pourbaix enabled guest synthesis (PEGS) strategy for RuO2 incorporation into MOF-808-P. a Pourbaix (redox potential-pH) diagram for Ru-H2O system (with a pH range of 5–10; concentration of Ru-based solution = 20 mM) constructed based on previously available data versus standard hydrogen electrode (SHE)29. Within the pH range it shows the range of potentials where a certain phase is thermodynamically stable, and the potential needed to transform one phase to another, i.e., the red arrow shows that to transform a soluble Ru-based precursor, perruthenate ion (RuO4−), to solid Ru-based guest (i.e., RuO2·2H2O) at a pH of ca. 8.5 (20 mM aqueous potassium perruthenate (KRuO4)), one needs minimum reduction potential (ΔEreduction) of 0.3–0.4 V (assuming an unaltered pH). A reductant, such as 2-tert-butyl-4-methylphenol (tBMP) with expected ca. 0.3 V to be oxidized, could be suitable. Diethyl ether (DE) is used as a solvent for tBMP. b Symbols for the scheme in (c), which illustrates RuO2 synthesis inside the cavity of pre-formed MOF-808-P using the hydrophobic reducing lipid tBMP. For clarity (i) the schematics of MOF-808-P is simplified as standard MOF-80836 and (ii) hydrogen atoms and carbon atoms for formates (HCOO−) are omitted in the metal–organic framework (MOF) cage

One concern for preparing the ship-in-a-bottle systems is the significant amount of guest depositing outside the hosts4,33, which creates a strong bias against the discovery of new functionalities in confinement6. Efforts to immobilize the precursor and to control the guest formation mostly inside the host include methods such as chemical grafting33,34 and electrostatic interactions35. These approaches, however, only work for a small portion of hosts with special chemistries (e.g., hosts with functionalizable parts or electrical charge). Enabled by the PEGS method, we may select the desired reagents with functionalities (i.e., temperature-controlled selective desorption and hydrophobic–hydrophilic interaction mentioned in Fig.1 and Supplementary Section 2.4) to control the loading position, and thus mitigate the outer surface deposition issue. Therefore, hosts no longer need to exhibit special chemistries to synthesize the right guests inside them.

The ability to synthesize a large variety of catalytic and optoelectronic materials with an even greater variety of available and synthesizable MOF materials is a combinatorial treasure trove of potential discoveries2,4,6,16. We demonstrate the synthesis of RuO2 confined within a MOF and then characterize the resulting products. The MOF used is MOF-808-P36 [Zr6O5(OH)3(BTC)2(HCOO)5(H2O)2, BTC = 1,3,5-benzenetricarboxylate], which is based on {Zr6O8} clusters (Fig. 1b) with the spn topology and has large cavity and aperture diameters (ca. 18 Å and ca. 14 Å, respectively). The MOF is stable in aqueous solution over a wide pH range of 3–1037. The synthesis of MOF-808-P is modified from MOF-808 and requires shorter time36,38. The good synthetic control of the loaded guests allows us to demonstrate that molecules can behave very differently on the guest surfaces. For example, molecules (such as CO and O2) adsorbed on the confined RuO2 at low temperatures (e.g., ≤150 °C) can exhibit a drastically different behavior compared with that on porous silica-supported RuO2. Most surprisingly, such guest inclusion inside the MOF host via PEGS turns inactive oxide surfaces into highly active catalysts. RuO2, which is usually easily deactivated at low temperatures by strong CO adsorption39,40,41, stays highly active in MOF confinement (>97% conversion after 12 h of continuous reaction) for CO oxidation. We believe that by using the PEGS method, many candidates, e.g., oxide, hydroxide and sulfide materials, can be expected to show other unique and surprising behaviors for catalysis and optoelectronics in confinement. In the following parts we describe in more detail the steps in applying the PEGS approach.

Results

Rational synthesis of RuO2 inside MOF-808-P

In revisiting the Pourbaix (redox potential-pH) diagrams of aqueous (element-H2O) systems27,28,29 (e.g., Ru-H2O system given in Fig. 1a), we realized that the reverse use of Pourbaix diagrams could guide the formation of insoluble compounds as long as the difference in the redox potentials between the reactants and the pH were chosen to make insoluble cluster formation thermodynamically favorable. For example, oxyanions (AxOyz−) in A-H2O (A) systems could form oxides and hydroxides27,28,29, where A is the desired element in the guest. Therefore, the PEGS strategy that we propose (detailed in Supplementary Section 1 and Supplementary Figure 1) can be more flexible and versatile than known methods2,4 and suitable for forming a range of insoluble guest compounds under relatively mild conditions inside pre-formed nanoporous hosts, e.g., MOFs and zeolites. As a demonstration, we have synthesized RuO2 inside a water-stable Zr-based MOF, MOF-808-P36, i.e., RuO2@MOF-808-P. We used potassium perruthenate (KRuO4) as the RuO2 precursor and 2-tert-butyl-4-methylphenol (tBMP, Fig. 1b) lipid as the reducing agent (Fig. 1; details in Supplementary Section 2.1).

According to the PEGS method tutorial detailed in Supplementary Section 1, from the Ru-H2O Pourbaix diagram (Fig. 1a) we have seen that at a pH of ca. 8.5 (20 mM aqueous KRuO4), the minimum ΔEreduction required to form RuO2·2H2O (the preform of RuO2) from the RuO4− (aq) domain is ca. 0.3–0.4 V. Therefore, a small reducing reagent which matches this ΔEreduction is required. Additionally, to perform the guest loading with the aforementioned position control, we need a reducing reagent that is hydrophobic and has temperature-controlled selective desorption capability (Supplementary Section 2.4). We have chosen the small lipid tBMP (Supplementary Figure 2), which meets the above-mentioned properties and is chemically similar to the well-known antioxidant lipid, butylated hydroxytoluene requiring ca. 0.3 V to be partially oxidized42,43. We expect that if it also provides ~0.3 V of oxidation potential, it may be sufficient to reduce RuO4− to RuO2·2H2O within a controlled pH range of 5–10.

We have verified that the MOF-808-P by itself remains white in color (i.e., no color change) in the KRuO4 solution, indicating no reaction in the MOF upon placement into the KRuO4 (aq) solution in the absence of tBMP. For the reaction, tBMP is first introduced into the MOF using diethyl ether (DE) as the solvent. With the aid of temperature-controlled selective desorption of tBMP and DE (Supplementary Section 2.4, Supplementary Figure 3)8,44, tBMP outside the MOF and all the DE was desorbed, while tBMP inside the MOF mostly remained to obtain tBMP@MOF-808-P. After immersing tBMP@MOF-808-P into the KRuO4 (aq) solution, the hydrophobic nature of tBMP kept it entrapped and solid products from the reduction of KRuO4 were obtained inside the MOF, minimizing the material formation outside the MOF (Fig. 1c). The initial product—hydrated RuO2 in the MOF—was further dehydrated to RuO2 (i.e., as-synthesized RuO2@MOF-808-P) at ca. 140 °C in N245. Furthermore, tunable loading amounts of the RuO2 guest were achieved by adjusting the mass ratio between tBMP and the MOF (thermogravimetric analysis in Supplementary Figure 4 and N2 adsorption measurements in Supplementary Figure 5).

RuO2@MOF-808-P characterizations and loading control

We have confirmed the preservation of the MOF host structure throughout the synthesis of RuO2@MOF-808-P by its mostly unaltered powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) patterns (Supplementary Figure 6). Pore occupation by the guest was revealed by the reduction in pore volume as shown in the pore distributions (Supplementary Figure 5d), which were derived from the N2 adsorption measurements. The incorporation of Ru-based guests in the MOF was confirmed with a combination of (i) energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) element mappings obtained from both scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (i.e., SEM-EDS, Supplementary Figure 7) and scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) (i.e., STEM-EDS, Supplementary Figure 8), and (ii) X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) (Supplementary Figure 9). The nature of the Ru-based guest was partly revealed from the XPS Ru 3p3/2 peak position (Supplementary Figure 10) at ca. 463.2 eV, which matches the standard Ru4+ peak46. X-ray absorption fine structure measurements (Supplementary Figure 11), using Ru foil and anhydrous RuO2 as references, identified the dominant Ru-O vector at ca. 1.78 Å47. Furthermore, a dark-field STEM (DF-STEM) image (Supplementary Figure 12) shows particles (ca. 15 Å in diameter) with electron diffraction fringes. The small particle size is consistent with the PXRD results, as no X-ray diffraction peak could be found for very small guest16. The space between two adjacent lines in the fringes is 2–2.5 Å, which matches the inter-planar spacing [d(011)/(101) or d(200)/(020)] expected for tetragonal RuO2 (space group: P42/mnm). Note that further reduction in adsorbed volume of N2 can be explained by partial pore collapse and/or amorphization24,48,49. This is supported by the disappearance of PXRD peaks (i.e., less ordered) above 40° for as-prepared RuO2@MOF-808-P as compared with dried MOF-808-P (Supplementary Figure 13). No significant potassium (K) residual could be found by inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) in the RuO2@MOF-808-P. This is also consistent with the SEM-EDS spectrum (Supplementary Figure 7, no peak at 3.314 keV for Kα) and XPS spectra (Supplementary Figure 9, no peak around 294.0 eV for K 2p).

To demonstrate the loading position control, we performed the redox reactions by adding KRuO4 (aq) solution to tBMP/DE/MOF-808-P mixture with and without the temperature-controlled selective desorption (Fig. 2a). By deliberately avoiding the temperature-controlled selective desorption, we obtained a significant material deposition on the outer surface of the MOF (Fig. 2a, top) in the dehydrated product. Since the tBMP/DE mixture on the outer surface forms droplets in contact with the KRuO4 (aq) solution to minimize the surface energy due to hydrophobic–hydrophilic repulsion, tBMP (outside the MOF) can only react with KRuO4 at the droplet-water interface forming a solid shell of hydrated RuO2. This is consistent with the spherical shell nanostructures deposited outside the MOF. The chemical composition of the spherical shell structures was verified by STEM-EDS (Fig. 2b). While both Zr and Ru signals are detected from the Zr-based MOF region after RuO2 loading, only Ru signal could be collected for the spherical shell nanostructures (highlighted in the yellow frame in Fig. 2b). In contrast, the dehydrated product (i.e., RuO2@MOF-808-P) from the reaction between KRuO4 (aq) solution and tBMP@MOF-808-P (with the temperature-controlled selective desorption) showed quite a clean MOF surface (Fig. 2a, bottom). Furthermore, the Ru signal mapping overlaps well with that for Zr and the MOF DF-STEM image (Fig. 2c). The significant outer surface deposition is therefore proved to be effectively inhibited by applying both temperature-controlled selective desorption and hydrophobic–hydrophilic repulsion.

Controllable RuO2 guest formation inside (or both inside and outside) MOF-808-P. a RuO2 can be formed both inside and outside the metal–organic framework (MOF), or only inside the MOF (i.e., RuO2@MOF-808-P) via temperature (T)-controlled selective desorption of the 2-tert-butyl-4−-methylphenol (tBMP) molecules outside the MOF. Dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (DF-STEM) images to the right show spherical shell structures on the outer surface of the MOF crystals (top, for RuO2 formed inside and outside the MOF, scale bars: 500 nm and 200 nm for left and right) vs. clean MOF crystal edges (bottom, for RuO2 loaded mostly inside the MOF, scale bars: 500 nm and 50 nm for left and right). The controlled deposition was further verified by STEM-energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) Zr and Ru mappings for b RuO2 formed inside and outside the MOF, scale bar: 200 nm, and c RuO2 loaded mostly inside the MOF, scale bar: 100 nm. The yellow frames in (b) highlight the Ru-based spherical shell structures. Raw images are provided as a Source Data file

Weakened CO and O interactions

In heterogeneous catalysis both catalyst surface structure and molecule surface adsorption have a significant influence on the catalytic performance39,50. We selected CO oxidation, which is relatively simple and well documented for a wide range of metal-based catalysts, as a prototypical reaction to understand the significance of molecule interactions with RuO239,51,52,53,54,55. Meanwhile, CO oxidation (i.e., elimination) is practically important for lowering automotive exhaust emissions, producing CO-free hydrogen for fuel cells and ammonia synthesis, and cleaning air, particularly at low temperatures and in humid air39,52,53,54. At low temperatures, the RuO2 is often regarded as a poor catalyst for CO oxidation because of surface passivation39,40. Below 150 oC, the dominant mechanism for this reaction is the Langmuir–Hinshelwood process39,40,56, in which the adsorbed CO combines with dissociated O2 species (i.e., O atoms) to produce CO2. Strong adsorption of CO and O species on RuO2, however, usually results in the formation of densely packed CO and O domains, where the limited surface desorption and diffusion of both species cause the low catalytic activity39,40,41. The PEGS synthesis of RuO2@MOF-808-P allows weaker CO and O interactions with RuO2 surface as compared to the commonly used porous silica-supported RuO2 catalyst (RuO2/SiO2)3,17,50,57, which will be discussed below. We prepared the RuO2/SiO2 with a conventional impregnation method58 and a commercially available amorphous SiO2 with mesoporosity (Supplementary Figures 14-16). Both RuO2/SiO2 and RuO2@MOF-808-P samples contained ca. 10 wt% Ru.

Ru-O interactions within the RuO2 nanostructures were tested by CO-temperature-programmed reduction (CO-TPR), which was performed with pre-oxidized samples equilibrated in flowing CO, and then gradually heated to find the minimum temperature where the lattice Ru could be reduced (Fig. 3a). The reduction peak for RuO2@MOF-808-P is much sharper and at a much lower temperature (~160 °C) than that from RuO2/SiO2 (~240 °C). The result was further confirmed by in situ X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) spectra, which showed that RuO2@MOF-808-P was reduced more significantly than RuO2/SiO2 by 5% CO at 30 oC (Supplementary Figure 17). The high reducibility of RuO2 (i.e., weaker Ru-O bonding) within the MOF is likely the result of an electronic confinement effect, which causes bonding orbital distortion16. Accordingly, we deduce that the interaction of O with the RuO2 surface in RuO2@MOF-808-P was significantly weakened.

CO and O interactions with RuO2 for RuO2/SiO2 and RuO2@MOF-808-P. a CO-temperature-programmed reduction (CO-TPR) in flowing CO and b temperature-dependent diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS) peak intensity reduction (due to CO desorption) for samples with only surface-adsorbed CO in flowing Ar. DRIFTS results for c RuO2/SiO2 and d RuO2@MOF-808-P with both surface-adsorbed CO and O in flowing Ar at various temperatures. The RuO2 (110) surface was taken as an example to assist our interpretation of the DRIFTS results in Table 1 (O in red, C in black, and green and blue for alternating rows of Ru with different {RuO6} octahedral orientation). Source data are provided as a Source Data file

The weaker interaction of CO with the MOF-confined RuO2 surface was revealed by temperature-dependent diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS) investigations40,56 (Fig. 3b–d). For temperature-dependent CO desorption characterization (Fig. 3b), samples were pre-treated in 5 vol% CO with 95 vol% He gas at room temperature and then heated up to 150 °C in flowing Ar. The on-top CO molecules (CO absorbed on coordinately unsaturated Ru) at the RuO2@MOF-808-P surface were lost from the surface above room temperature, and at 150 °C the main peak at 2061 cm−1 almost disappeared (Fig. 3b). In contrast, for RuO2/SiO2 no CO desorption could be observed below 100 oC and 70% of the corresponding peak intensity (2076 cm−1, Fig. 3b) remains at 150 oC.

Under reaction conditions close to room temperature (ca. 30 °C), DRIFTS bands also reveal the packing state of the adsorbed species, with densely packed CO adsorption domains observed on RuO2/SiO2 but not on RuO2@MOF-808-P (Fig. 3c, d). In this experiment, DRIFTS spectra of both samples were collected by adsorbing CO (in 1 vol% CO, 20 vol% O2, and 79 vol% He) at room temperature and then heating up in Ar. The DRIFTS bands are summarized in Table 1 with data interpretation supported by previous studies40,56. The control experiment on pure MOF material shows no CO adsorption (no similar peak feature found in the MOF-808-P spectra, Supplementary Figure 18). The shift of on-top CO stretching frequency (2076 cm−1 for RuO2/SiO2 versus 2055 cm−1 for RuO2@MOF-808-P) is attributed to the disappearance of the densely packed CO domains in RuO2@MOF-808-P40,56. Meanwhile, the weakened interaction of O with RuO2 surface, which is suggested by CO-TPR, is also supported by the change of bridging CO frequency (2027 cm−1 for RuO2/SiO2 versus 2005 cm−1 for RuO2@MOF-808-P) showing fewer O surrounding CO on the surface of the MOF-confined RuO240,56.

Overall by confining the RuO2 inside the MOF cavity (i) the interactions between O/CO and the catalyst (i.e., RuO2) surface are weakened; and (ii) the formation of densely packed CO domains are inhibited. As a consequence, the adsorbed CO is more easily oxidized. This is further reflected by the temperature-dependent DRIFTS results (Fig. 3c, d): surface CO is completely eliminated at 100 oC on the RuO2@MOF-808-P catalysts, whereas the majority of CO molecules are still present on RuO2/SiO2 at 100 °C. The ability to modulate the surface adsorption of CO and O species on RuO2 contained in the MOF cavity have motivated us to compare the activities of CO oxidation catalyzed by RuO2@MOF-808-P and RuO2/SiO2, respectively50,51,57,59,60.

RuO2@MOF-808-P as a low-temperature CO oxidation catalyst

Under all reaction conditions shown in Fig. 4, the RuO2@MOF-808-P catalysts demonstrate superior performance compared with the RuO2/SiO2 catalysts (ca. 5% vs. no CO conversion at 30 °C; 100% at 65 °C vs. 100% at 150 °C). Meanwhile, both catalysts achieve better CO conversions at low temperature after activation in O2 compared with activation in Ar (Fig. 4a), suggesting that oxygen-rich Ru oxide is the active surface structure for low-temperature CO oxidation61. From the CO conversion data we calculate the apparent activation energies from the MOF-confined and SiO2-supported RuO2 to be Ea = 86 kJ mol−1 and Ea = 145 kJ mol−1, respectively, with the MOF-confined catalyst activation energy at the low end of the measured RuO2 activation energies (Fig. 4b)39. The remarkably higher turnover frequency (TOF) for RuO2@MOF-808-P (Fig. 4c) than that for RuO2/SiO2 and those shown in Supplementary Table 162 is also likely the result of the presence of loosely packed CO molecules. As controls, we have verified that MOF-808-P and tBMP@MOF-808-P are inactive for CO oxidation (Supplementary Figure 19). We can also exclude any significant contribution from the precursor (i.e., KRuO4) to the superior catalytic performance of RuO2@MOF-808-P by showing that the CO oxidation performance for RuO2/SiO2 with RuCl3 is better than that for RuO2/SiO2 with KRuO4 (Supplementary Figure 20).

CO oxidation performance over RuO2/SiO2 and RuO2@MOF-808-P catalysts. a CO conversion profiles at weight hourly space velocity (WHSV) of 2000 L gRu−1 h−1 with 15 mg catalysts. b Arrhenius plots and calculated apparent activation energies (Ea). c Chemisorbed CO at −50 °C (to prevent CO2 formation during the measurements) and calculated turnover frequency (TOF, conversion per unit site per unit time). d Stability test using O2-activated RuO2/SiO2 and RuO2@MOF-808-P catalysts (2000 L gRu−1 h−1, 15 mg catalysts) at 100 °C. Experimental details are given in Supplementary Section 4.2. Source data are provided as a Source Data file

The above results indicate that RuO2@MOF-808-P is a unique low-temperature CO oxidation catalyst. At 100 °C and 2000 L gRu−1 h−1 CO flow rate, it still sustained >97% conversion capability after 12 h, whereas under the same conditions RuO2/SiO2 deactivated completely within 20 min (Fig. 4d). This is consistent with our CO-TPR and DRIFTS results (Fig. 3). We suggest that, for the RuO2/SiO2 catalysts upon being exposed to the continuously fed reaction gas at low temperatures, the densely packed surface CO and O domains form and prevent the CO–O reaction (Fig. 4c), leading to rapid deactivation at 100 °C (Fig. 4d).

By forming RuO2@MOF-808-P using the PEGS strategy, we allow adsorbed CO to react with adsorbed O at low temperature (Fig. 3d) due to the weakened CO and O interactions with the RuO2 surface. These modulated interactions can be attributed to the confined microenvironment provided by the MOF50,51,59 and/or the unique surface chemistry of RuO2 introduced by the PEGS method. Additionally, around 30 °C, we have also observed drastically different CO conversion performances (Supplementary Figures 21 and 22); whereas the RuO2/SiO2 catalyst is completely deactivated after 12 min, the MOF-confined one still has >40% conversion after 2 h and can be easily re-generated. This further promises normal ambient-condition-based CO removal, in which pure thermal stability is no longer a major concern but potential interactions of the catalysts with water should be considered. In this context, by treating RuO2@MOF-808-P with water vapor at 100 °C, we proved that (i) the MOF structure is mostly preserved (Supplementary Figure 23) and (ii) the RuO2@MOF-808-P retains its high activity (Supplementary Figure 24), which has been a challenge for recent MOF-based catalyst development63.

Discussion

In summary, we use a preparation of RuO2@MOF-808-P as a tutorial to introduce the PEGS strategy, which enables the formation of guests confined in metastable hosts by rational selection of the precursors and conditions for their synthesis. The successful synthesis of RuO2@MOF-808-P results in modulated CO/O adsorption behavior and a remarkable improvement in the CO oxidation performance on the RuO2 surface at low temperatures. The PEGS method can be extended to other guests and nanoporous hosts with reasonable stability under desired synthesis conditions (Supplementary Figure 25)24,64. In theory, the PEGS approach is applicable to metals, oxides, hydroxides and sulfides65 as long as their relevant Pourbaix diagrams indicate the feasibility of their formation. So far, we have attempted oxides (i.e., RuO2 and MnOx) with different MOFs (MOF-808-P and DUT-6766) and a zeolite Y20 (Supplementary Figure 25), and Pd metal particles with MOF-808-P (Supplementary Figures 26–28). Furthermore, benefiting from the recent development of the materials genome approach and the continuous expansion of available databases of Pourbaix diagrams or related phase diagrams (e.g., Materials Project67,68,69,70), it may even be possible to design guests with more complicated chemistries (e.g., nitrides, phosphides and multi-element compounds). Additionally, considering parameters determining the reactivity in other solvents, diagrams similar to Pourbaix diagrams may be constructed for water-free synthesis. The functions of such guests are not limited solely to catalysis, but could be used to produce a wide variety of optoelectronic materials2,18. We believe that this rational synthesis approach to guest functionality in MOF hosts will become a general tool for the systematic synthesis of homologous series of guests confined in porous hosts, as well as a route for combinatorial discovery of materials towards novel practical significance.

Methods

Sample preparation

Detailed experimental methods can be found in the Supplementary Information. The considerations to plan a guest synthesis are mentioned in the Supplementary Information 1 and 2.1. To prepare the RuO2@MOF-808-P, briefly, MOF-808-P was produced first using a method based on a previously reported synthesis (Supplementary Section 2.3)36. The dried MOF-808-P was loaded with tBMP-in-DE solution (50 mg tBMP with 1 ml DE, detailed in Supplementary Section 2.4). The tBMP-to-MOF-808-P mass ratio in the mixture was adjusted to control the final loading of RuO2 (Supplementary Figure 5a). The as-prepared tBMP/DE@MOF-808-P powder was then heated at 120 ± 5 °C under N2 flow for ca. 1 h (i.e., temperature-controlled selective desorption) to remove the tBMP outside the MOF and DE (Supplementary Section 2.4, Supplementary Figure 3). The treated material was immersed in an excess amount of KRuO4 aqueous solution (20 mM) for ca. 4 h to form hydrous RuO2@MOF-808-P. It was finally collected by filtration and dehydrated at ca. 140 °C to give as-synthesized RuO2@MOF-808-P (Supplementary Section 2.5). Methods for RuO2/SiO2 preparation and characterizations are given in Supplementary Section 3.1.

Material characterization

The methods for RuO2@MOF-808-P characterizations are given in Supplementary Section 2.6.

Surface adsorption and CO oxidation investigations

The methods for surface adsorption and CO oxidation investigations are given in Supplementary Section 4.1.

Data availability

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are included in the paper and its supplementary information files, and are available on request from the corresponding authors. The raw images and/or source data underlying Figs. 2–4 and Supplementary Figures. 3–25, 27 and 28 are provided as a Source Data fileset, which is also available in figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7588250).

References

Herron, N. & Corbin, D.R. (eds) Inclusion Chemistry with Zeolites: Nanoscale Materials by Design (Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, 1995).

Laeri, F., Schüth, F., Simon, U. & Wark, M. (eds) Host-Guest-Systems Based on Nanoporous Crystals (Wiley-VCH GmbH & Co. KGaA, Darmstadt, 2003).

An, B. et al. Confinement of ultrasmall Cu/ZnOx nanoparticles in metal–organic frameworks for selective methanol synthesis from catalytic hydrogenation of CO2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 3834–3840 (2017).

Chen, L., Luque, R. & Li, Y. Controllable design of tunable nanostructures inside metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 46, 4614–4630 (2017).

Yang, Y. et al. Photophysical properties of a post-self-assembly host/guest coordination cage: visible light driven core-to-cage charge transfer. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 6, 1942–1947 (2015).

Allendorf, M. D. et al. Guest-induced emergent properties in metal–organic frameworks. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 6, 1182–1195 (2015).

Wang, T. et al. Bottom-up formation of carbon-based structures with multilevel hierarchy from MOF–guest polyhedra. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 6130–6136 (2018).

Wang, T. et al. Functional conductive nanomaterials via polymerisation in nano-channels: PEDOT in a MOF. Mater. Horiz. 4, 64–71 (2017).

Corma, A. & Garcia, H. Supramolecular host-guest systems in zeolites prepared by ship-in-a-bottle synthesis. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2004, 1143–1164 (2004).

Moller, K. & Bein, T. Inclusion chemistry in periodic mesoporous hosts. Chem. Mater. 10, 2950–2963 (1998).

Fujita, M. et al. Self-assembly of ten molecules into nanometre-sized organic host frameworks. Nature 378, 469–471 (1995).

Lee, J. et al. Metal–organic framework materials as catalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 1450 (2009).

Meilikhov, M. et al. Metals@MOFs - loading MOFs with metal nanoparticles for hybrid functions. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 3701–3714 (2010).

Juan-Alcañiz, J., Gascon, J. & Kapteijn, F. Metal–organic frameworks as scaffolds for the encapsulation of active species: State of the art and future perspectives. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 10102–10118 (2012).

Pan, X. & Bao, X. The effects of confinement inside carbon nanotubes on catalysis. ACC Chem. Res. 44, 553–562 (2011).

Corma, A., García, H. & Llabrés i Xamena, F. X. Engineering metal organic frameworks for heterogeneous catalysis. Chem. Rev. 110, 4606–4655 (2010).

Zhao, M. et al. Metal–organic frameworks as selectivity regulators for hydrogenation reactions. Nature 539, 76–80 (2016).

Stucky, G. D. & Mac Dougall, J. E. Quantum confinement and host/guest chemistry: Probing a new dimension. Science 247, 669–678 (1990).

Chen, L., Luque, R. & Li, Y. Encapsulation of metal nanostructures into metal–organic frameworks. Dalt. Trans. 47, 3663–3668 (2018).

Herron, N. A cobalt oxygen carrier in zeolite Y. A molecular “ship in a bottle”. Inorg. Chem. 25, 4714–4717 (1986).

Farrusseng, D., Aguado, S. & Pinel, C. Metal-organic frameworks: opportunities for catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 7502–7513 (2009).

Furukawa, H., Cordova, K. E., O’Keeffe, M. & Yaghi, O. M. The chemistry and applications of metal-organic frameworks. Science 341, 1230444 (2013).

Moghadam, P. Z. et al. Development of a Cambridge structural database subset: a collection of metal–organic frameworks for past, present, and future. Chem. Mater. 29, 2618–2625 (2017).

Howarth, A. J. et al. Chemical, thermal and mechanical stabilities of metal–organic frameworks. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 15018 (2016).

Lollar, C. T. Interior decoration of stable metal–organic frameworks. Langmuir 32, 13795–13807 (2018).

Shen, K. et al. Ordered macro-microporous metal-organic framework single crystals. Science 359, 206–210 (2018).

Pourbaix, M. Atlas of Electrochemical Equilibria in Aqueous Solutions (Pergamon Press, New York, 1966).

Campbell, J. A. & Whiteker, R. A. A periodic table based on potential-pH diagrams. J. Chem. Educ. 46, 90–92 (1969).

Povar, I. & Spinu, O. Ruthenium redox equilibria: 3. Pourbaix diagrams for the systems Ru-H2O and Ru-Cl--H2O. J. Electrochem. Sci. Eng. 6, 145–153 (2016).

Wills, L. A. et al. Group additivity-Pourbaix diagrams advocate thermodynamically stable nanoscale clusters in aqueous environments. Nat. Commun. 8, 15852 (2017).

Exner, K. S. & Over, H. Kinetics of electrocatalytic reactions from first-principles: a critical comparison with the ab initio thermodynamics approach. ACC Chem. Res. 50, 1240–1247 (2017).

Revie, R. W. & Uhlig, H. H. Corrosion and Corrosion Control: An Introduction to Corrosion Science and Engineering (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New Jersey, 2008).

Coupry, D. E. et al. Controlling embedment and surface chemistry of nanoclusters in metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Commun. 52, 5175–5178 (2016).

Hwang, Y. K. et al. Amine grafting on coordinatively unsaturated metal centers of MOFs: consequences for catalysis and metal encapsulation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 4144–4148 (2008).

Wei, Y., Han, S., Walker, D. A., Fuller, P. E. & Grzybowski, B. A. Nanoparticle core/shell architectures within MOF crystals synthesized by reaction diffusion. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 7435–7439 (2012).

Jiang, J. et al. Superacidity in sulfated metal–organic framework-808. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 12844–12847 (2014).

Zheng, H.-Q. et al. MOF-808: a metal–organic framework with intrinsic peroxidase-like catalytic activity at neutral pH for colorimetric biosensing. Inorg. Chem. 57, 9096–9104 (2018).

Furukawa, H. et al. Water adsorption in porous metal–organic frameworks and related materials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 4369–4381 (2014).

Over, H. Surface chemistry of ruthenium dioxide in heterogeneous catalysis and electrocatalysis: From fundamental to applied research. Chem. Rev. 112, 3356–3426 (2012).

Farkas, A., Mellau, G. C. & Over, H. Novel insight in the CO oxidation on RuO2 (110) by in situ reflection−absorption infrared spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. C 113, 14341–14355 (2009).

Assmann, J. et al. Heterogeneous oxidation catalysis on ruthenium: bridging the pressure and materials gaps and beyond. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 20, 184017 (2008).

Yohe, G. R. et al. The oxidation of 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methylphenol. J. Org. Chem. 21, 1289–1292 (1956).

Richards, J. A. & Evans, D. H. Electrochemical oxidation of 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-isopropylphenol. J. Electroanal. Chem. Interfacial Electrochem. 81, 171–187 (1977).

Le Ouay, B. et al. Nanostructuration of PEDOT in porous coordination polymers for tunable porosity and conductivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 10088–10091 (2016).

Keattch, C. J. & Redfern, J. P. The preparation and properties of a hydrous ruthenium oxide. J. Less Common Met. 4, 460–465 (1962).

Velázquez-Palenzuela, A. et al. Structural properties of unsupported Pt−Ru nanoparticles as anodic catalyst for proton exchange membrane fuel cells. J. Phys. Chem. C 114, 4399–4407 (2010).

Wang, X. et al. Uncoordinated amine groups of metal–organic frameworks to anchor single Ru sites as chemoselective catalysts toward the hydrogenation of quinoline. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 9419–9422 (2017).

Fang, Z., Bueken, B., De Vos, D. E. & Fischer, R. A. Defect-engineered metal-organic frameworks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 7234–7254 (2015).

Cheetham, A. K., Bennett, T. D., Coudert, F. X. & Goodwin, A. L. Defects and disorder in metal organic frameworks. Dalton Trans. 45, 4113–4126 (2016).

Fu, Q. & Bao, X. Surface chemistry and catalysis confined under two-dimensional materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 46, 1842–1874 (2017).

Sun, M. et al. Catalysis under shell: improved CO oxidation reaction confined in Pt@h-BN core–shell nanoreactors. Nano Res. 10, 1403–1412 (2017).

Royer, S. & Duprez, D. Catalytic oxidation of carbon monoxide over transition metal oxides. ChemCatChem 3, 24–65 (2011).

Ertl, G. Reactions at surfaces: from atoms to complexity (Nobel lecture). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 3524–3535 (2008).

Freund, H. J., Meijer, G., Scheffler, M., Schlögl, R. & Wolf, M. CO oxidation as a prototypical reaction for heterogeneous processes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 10064–10094 (2011).

Lamberti, C., Zecchina, A., Groppo, E. & Bordiga, S. Probing the surfaces of heterogeneous catalysts by in situ IR spectroscopy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 39, 4951–5001 (2010).

Aßmann, J., Löffler, E., Birkner, A. & Muhler, M. Ruthenium as oxidation catalyst: bridging the pressure and material gaps between ideal and real systems in heterogeneous catalysis by applying DRIFT spectroscopy and the TAP reactor. Catal. Today 85, 235–249 (2003).

Janda, A., Vlaisavljevich, B., Lin, L.-C., Smit, B. & Bell, A. T. Effects of zeolite structural confinement on adsorption thermodynamics and reaction kinetics for monomolecular cracking and dehydrogenation of n-butane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 4739–4756 (2016).

Spinacé, E. V. & Vaz, J. M. Liquid-phase hydrogenation of benzene to cyclohexene catalyzed by Ru/SiO2 in the presence of water–organic mixtures. Catal. Commun. 4, 91–96 (2003).

Li, H., Xiao, J., Fu, Q. & Bao, X. Confined catalysis under two-dimensional materials. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 5930–5934 (2017).

Jiang, H. et al. Au@ZIF-8: CO oxidation over gold nanoparticles deposited to metal−organic framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 11302–11303 (2009).

Park, J.-N. et al. Room-temperature CO oxidation over a highly ordered mesoporous RuO2 catalyst. React. Kinet. Mech. Catal. 103, 87–99 (2011).

Joo, S. H. et al. Size effect of ruthenium nanoparticles in catalytic carbon monoxide oxidation. Nano Lett. 10, 2709–2713 (2010).

Gascon, J., Corma, A., Kapteijn, F. & Llabrés i Xamena, F. X. Metal organic framework catalysis: Quo vadis? ACS Catal. 4, 361–378 (2014).

Prodinger, S. et al. Stability of zeolites in aqueous phase reactions. Chem. Mater. 29, 7255–7262 (2017).

Ning, J., Zheng, Y., Young, D., Brown, B. & Nešić, S. Thermodynamic study of hydrogen sulfide corrosion of mild steel. Corrosion 70, 375–389 (2014).

Bon, V., Senkovska, I., Baburin, I. A. & Kaskel, S. Zr- and Hf-based metal–organic frameworks: tracking down the polymorphism. Cryst. Growth Des. 13, 1231–1237 (2013).

Materials Project. http://materialsproject.org (2018).

Jain, A. et al. Commentary: The materials project: a materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation. APL Mater. 1, 011002 (2013).

Singh, A. K. et al. Electrochemical stability of metastable materials. Chem. Mater. 29, 10159–10167 (2017).

Persson, K. A., Waldwick, B., Lazic, P. & Ceder, G. Prediction of solid-aqueous equilibria: Scheme to combine first-principles calculations of solids with experimental aqueous states. Phys. Rev. B 85, 235438 (2012).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Prof. Dr. Herbert Over and Prof. Dr. Martin Muhler for discussion on low-temperature CO oxidation with RuO2-based catalyst. The authors also acknowledge Prof. Judith L. MacManus-Driscoll for providing XPS facility and Dr. Na Ta for assisting in the STEM characterizations. T.W. thanks Assist. Prof. Zahari P. Vinarov for the suggestion about using small antioxidant lipid and Kara D. Fong for the inspirational discussion about MnO2 formed from KMnO4. This work is funded by the European Research Council (ERC) grant to S.K.S., EMATTER (# 280078). Q.F. thanks the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21688102 and No. 21825203) and Ministry of Science and Technology of China (No. 2016YFA0200200), and Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (No. XDB17020000) for funding. A.K.C. acknowledges the Ras Al Khaimah Center for Advanced Materials (RAK-CAM). T.W. expresses his appreciation to the China Scholarship Council (CSC) for funding and the EPSRC Centre for Doctoral Training in Sensor Technologies and Applications (EP/L015889/1 and 1566990) for support. W.L. acknowledges the EPSRC grants (EP/L011700/1 and EP/N004272/1) and the Isaac Newton Trust [Minute 13.38(k)]. Pourbaix diagrams can be generated from the Materials Project (http://materialsproject.org) using its open-sourced database.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The manuscript is written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript. T.W., who is supervised by S.K.S. and co-advised by A.K.C. and R.V.K., initiated the project and developed the PEGS. X.B., Q.F., S.K.S., A.K.C., T.W. and L.G. conceived the idea about using RuO2@MOF-808-P for CO oxidation. T.W. prepared RuO2@MOF-808-P. J.H., S.J.A.H., J.T.G., W.L., S.G. and T.W. characterized RuO2@MOF-808-P guided by S.K.S., A.K.C., R.V.K. and M.-M.T. L.G. and J.D. characterized CO adsorption and CO oxidation supervised by X.B. and Q.F. T.W., L.G. and J.H. prepared the initial manuscript instructed by S.K.S., X.B., Q.F., A.K.C., R.V.K. and M.-M.T. with input from all the authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A relevant patent is filed by T.W., S.K.S., Q.F. and L.G. (GB1813334.8). The other authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Journal peer review information: Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, T., Gao, L., Hou, J. et al. Rational approach to guest confinement inside MOF cavities for low-temperature catalysis. Nat Commun 10, 1340 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-08972-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-08972-x

This article is cited by

-

Fundamental Perspectives on the Electrochemical Water Applications of Metal–Organic Frameworks

Nano-Micro Letters (2023)

-

Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs): The Next Generation of Materials for Catalysis, Gas Storage, and Separation

Journal of Inorganic and Organometallic Polymers and Materials (2023)

-

Tuning the functionality of metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) for fuel cells and hydrogen storage applications

Journal of Materials Science (2023)

-

Angstrom-confined catalytic water purification within Co-TiOx laminar membrane nanochannels

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Breaking pore size limit of metal—organic frameworks: Bio-etched ZIF-8 for lactase immobilization and delivery in vivo

Nano Research (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.