Abstract

Stimuli-responsive behaviors of flexible metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) make these materials promising in a wide variety of applications such as gas separation, drug delivery, and molecular sensing. Considerable efforts have been made over the last decade to understand the structural changes of flexible MOFs in response to external stimuli. Uniform pore deformation has been used as the general description. However, recent advances in synthesizing MOFs with non-uniform porous structures, i.e. with multiple types of pores which vary in size, shape, and environment, challenge the adequacy of this description. Here, we demonstrate that the CO2-adsorption-stimulated structural change of a flexible MOF, ZIF-7, is induced by CO2 migration in its non-uniform porous structure rather than by the proactive opening of one type of its guest-hosting pores. Structural dynamics induced by guest migration in non-uniform porous structures is rare among the enormous number of MOFs discovered and detailed characterization is very limited in the literature. The concept presented in this work provides new insights into MOF flexibility.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Flexible metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) are attracting an ever-increasing amount of attention because their stimuli-responsive structures make them highly competitive in various applications such as gas separation1,2, drug delivery3, and molecular sensing4,5. In particular, some flexible MOFs show stepped gas adsorption isotherms that arise directly from their structural properties. Consequently, gas separation in these MOFs, which is based on the adsorption discrepancy of different gases, can be achieved simply with a small temperature or pressure swing6. This greatly reduces the regeneration energies needed and makes flexible MOFs promising in replacing traditional adsorbents for energy-efficient gas separation. Many pioneering works have been carried out to understand MOF structural flexibility related to such stepped gas adsorption isotherms7,8,9. Established theories envisage that when interacting with gas molecules, MOF pores deform for adsorption through linker rotation and/or framework distortion, which leads to the abrupt increase/decrease in gas adsorption capacities8. In most cases, it is considered that in a flexible MOF, all pores capable of gas adsorption undergo a similar structural change. This assumption is used by default because most of the flexible MOFs studied in detail have uniform porous structures with only one type of pores that have the same size, shape, and environment7,8,9. For example, MIL-5310, one of the most studied flexible MOFs with uniform porous structures, shows only one type of quadrilateral prism pores of 8.5 Å diameter11. In recent years, MOFs with non-uniform porous structures, i.e., with multiple types of pores which vary in size, shape, and environment, have been shown to also have structural flexibility and unique gas adsorption features12. It is thus not appropriate to explain the structural flexibility of these MOFs as a result of the dynamic behavior of one type of pores. One good example is DUT-49, which shows unusual structural flexibility related to stepped negative gas adsorption features12. Its negative gas adsorption takes place when gas molecules such as CH4 migrate from its micropores to mesopores, provoking an enormous structural contraction that reduces the amount of gas adsorbed. Noticeably, although this work indicates the internal shuffling of gas molecules between different pores of DUT-49, this claim was unfortunately not supported by any dynamic study. It motivated us to perform a detailed dynamic analysis of guest molecules inside a flexible non-uniform porous MOF. We believe that this well addresses a fundamentally important issue in the understanding of structural transitions and guest-host interactions in flexible MOFs.

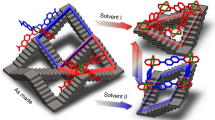

Here, we decide to study zeolitic imidazolate framework 7 (ZIF-7) which has a non-uniform porous structure showing structural flexibility and stepped adsorption isotherms during the uptake of guest molecules such as CO213. It is an important member of the MOF subgroup, ZIFs, some of which are noted for their high hydrothermal stability and structural similarity to aluminosilicate zeolites14. ZIF-7 (Zn(bIm)2, bIm: benzimidazolate) is composed of zinc atoms connected by bIm linkers in tetrahedral coordination. As indicated by the pore size distribution analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1), ZIF-7 has four types of pores, including two types of six-member-ring pores, one type of four-member-ring pores, and the sodalite cage (Fig. 1a). Type A six-member-ring pore (pore A) has the largest void space in ZIF-7 and has long been considered the one to proactively open for gas adsorption15,16,17. However, we found that the structural flexibility and stepped CO2 adsorption isotherms of ZIF-7 is in fact related to CO2 migration between its different types of pores, something that we implied in our previous work18. Although formerly we were prohibited from giving a clear description of the migration route due to the lack of evidence, in this present work we are able to include extensive in situ experimental and computational analysis revealing the CO2 migration pathways and its relationship with the adsorption-stimulated structural transitions in ZIF-7. It is demonstrated that in fact CO2 molecules first weakly bind to the adjacent type B six-member-ring pore (pore B) when pore A is closed. With the accumulation of CO2 molecules in pore B, the shared linker between pores A and B rotates in a manner that leads to CO2 flowing from pore B into pore A, resulting in an abrupt increase in CO2 adsorption capacity and inducing an overall structural transformation in ZIF-7. Our results explain the long-discussed nature of ZIF-7 structural flexibility and its CO2 adsorption mechanism. We believe that this sequential pore filling mechanism discussed here will contribute to the fundamental understanding of the structural−property relationships in flexible MOFs.

ZIF-7 structure and its CO2 adsorption behavior. a The building unit, sodalite cage, of ZIF-7 with two types of six-member-ring pores (A, B) and one type of four-member-ring pores on its walls. Part of the framework is simplified by replacing Zn−bIm−Zn with Zn−Zn (bIm = benzimidazolate, C7N2H5, Zn: gray). In our previous work18, we have demonstrated CO2 molecules prefer to be adsorbed in six-member-ring pores, as shown here. In addition, there are more CO2 molecules adsorbed in pore B than in pore A. CO2: red. The symmetry of CO2 has been disregarded for clarity. b CO2 adsorption isotherms of ZIF-7 at 195 and 298 K, pCO2 = 1–100 kPa, illustrated by the structural behaviors of ZIF-7. c The structural change of pore A in the ZIF-7-II to ZIF-7-I phase transition. Zn: gray; N: blue; C: green; H: white. d The structural change of pore B in the ZIF-7-II to ZIF-7-I phase transition. Zn: gray; N: blue; C: green; H: white. See the crystal structures of ZIF-7-I and ZIF-7-II in Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 3

Results

Initial CO2 adsorption

Figure 1b shows the CO2 adsorption isotherms of ZIF-7 at 195 and 298 K (see Supplementary Table 2 for the tabulated data). At 298 K, a CO2 adsorption transition pressure is observed at 40−60 kPa. Below 40 kPa, ZIF-7 is not able to adsorb much CO2 (0.2 mmol g−1). At 60 kPa, ZIF-7 reaches a much higher CO2 adsorption capacity (1.3 mmol g−1). The structural transformation corresponding to this abrupt increase in CO2 adsorption capacity has been reported in our previous work (ZIF-7-II to ZIF-7-I phase transition, Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 3)19. As seen in Fig. 1c, the six-member-ring pore A shows a structural change induced by linker rotation, which results in an increase in pore size for CO2 accommodation (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1). The dynamic behavior of the linkers has previously been described as an opening of the gate of pore A. However, if we look closely at the structure of pore A at high CO2 pressure (ZIF-7-I phase), it can be noticed that the window (or gate) of pore A, whose diameter is 3 Å, is still not large enough for easy access of CO2 molecules whose kinetic diameter is 3.3 Å20. Thus, CO2 adsorption in ZIF-7 is not simply a consequence of pore A window expansion.

CO2 adsorption at 195 K offers additional information that helps further understand the process in the structure. At this temperature, CO2 adsorption takes place in two stages. At low CO2 pressure (10 kPa), ZIF-7 reaches two-thirds of its full CO2 adsorption capacity at current temperature (2.7 mmol g−1). Further CO2 adsorption takes place over a narrow pressure range before its full CO2 adsorption capacity is reached at 30 kPa (4.2 mmol g−1). In situ synchrotron X-ray powder diffraction (SXRD) was employed to monitor CO2 adsorption in ZIF-7 at 195 K (Fig. 2a), in the hope of relating both CO2 adsorption stages with ZIF-7 structural transformations, as reported previously13,21. It is found that the ZIF-7-II to ZIF-7-I phase transition takes place over a higher pressure range and is related to the second CO2 adsorption stage. The amount of CO2 adsorbed during the ZIF-7-II to ZIF-7-I phase transition at 195 K (1.5 mmol g−1) is comparable to that at 298 K (1.1 mmol g−1). No structural transformation can be observed to rationalize the first CO2 adsorption stage at 195 K. This means that ZIF-7 was in ZIF-7-II phase when the initial CO2 adsorption took place. As pore A in ZIF-7-II phase has no CO2 adsorption capability due to its narrow pore space, it is reasonable to conclude that the initial CO2 adsorption at 195 K takes place somewhere other than pore A. Moreover, initial CO2 adsorption appears to lead to the ZIF-7-II to ZIF-7-I phase transition in which the second CO2 adsorption stage occurs.

Phase transition and CO2 diffusion in ZIF-7. a In situ SXRD data of ZIF-7 at T = 195 K, p(CO2) = 0–41 kPa. λ = 0.82634(1) Å. At 0–23 kPa, the diffraction pattern corresponds to ZIF-7-II. Above 30 kPa, the diffraction pattern of ZIF-7-I dominates. b The Q dependence of the CO2 transport diffusion coefficient D in ZIF-7 at a CO2 loading of 1.3 mmol g−1 and T = 298 K, fitted by a 4th-order polynomial function. Error bars are calculated using Supplementary Equation 6. Dt: transport diffusivity. Dt = D(0). Ds: self-diffusivity. Dt = Ds(∂ lnp/∂ lnc). p is CO2 pressure in kPa and c is CO2 uptake at p in mmol g−1. See Supplementary Discussion for detailed analysis. c The Q dependence of the CO2 transport diffusion coefficient D in ZIF-7 at a CO2 loading of 1.3 mmol g−1 and T = 225 K, fitted by a linear function. Error bars are calculated using Supplementary Equation 6

Previously, the six-member-ring pore B adjacent to pore A was identified as the preferred CO2 adsorption site (Fig. 1a) when we studied CO2 adsorption geometry in ZIF-7-I at 300 K by neutron powder diffraction (ND)18. Pore B was later demonstrated to be a preferred adsorption site for CO2 and some other guest molecules by works from others13,21,22. Since pore B has identical structures in both ZIF-7-I and ZIF-7-II phases (Fig. 1d), it is possible that pore B in ZIF-7-II is where the CO2 adsorption at 195 K begins. However, it is difficult to validate this hypothesis by directly determining CO2 locations in ZIF-7-II at 195 K using diffraction methods. This is because ZIF-7-II has low symmetry (P-1) and a large unit cell (V = 7917 Å3), Rietveld refinement based on diffraction data is not able to define a reliable ZIF-7-II (CO2) crystal structure. Hence, we needed to find alternative evidence in order to identify the location at which CO2 adsorption in ZIF-7-II begins. Since transport diffusion can reflect the collective motion of gas molecules caused by local concentration gradients, CO2 transport diffusivity in ZIF-7-I was measured to show that, to access the structure, CO2 adsorbs preferentially in pore B rather than in pore A. The measurement was done using quasi-elastic neutron scattering (QENS) at 298 K and a CO2 loading of 1.3 mmol g−1. The length and time scales of QENS match those of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and good agreement are often found between experimental and theoretical results. Sample dependence, due to factors such as surface barriers and structural defects, can be eliminated in QENS results. Detailed QENS data analysis can be found in Supplementary Discussion (Supplementary Figs. 3–5). The measured CO2 transport diffusivity in ZIF-7-I (6.3(7) × 10−9 m2 s−1, Fig. 2b) was compared with those experimentally obtained in ZIF-8 at the same temperature (0.4(3) × 10−9 m2 s−1)23,24,25,26. We did this comparison because ZIF-8 is an analog of ZIF-7 but has only one type of CO2 hosting pore (see pore size distribution analysis in Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1) connected by six-member-ring windows with similar size (diameter 3.4 – 4.1 Å) and geometry to those of pore A in ZIF-7-I (Supplementary Fig. 6)14,23. In contrast, pore B in ZIF-7-I and ZIF-7-II has larger windows of 4.6 – 5.3 Å diameter. The one-order-of-magnitude larger CO2 transport diffusivity in ZIF-7-I compared with ZIF-8 indicates that, in accessing ZIF-7-I, CO2 prefers pore B to pore A. Since the structure of pore B is identical in both ZIF-7-I and ZIF-7-II phases and pore A has smaller pore space in ZIF-7-II than in ZIF-7-I, pore B is expected to be the initial site for CO2 adsorption in ZIF-7-II.

The absence of initial CO2 adsorption prior to the ZIF-7-II to ZIF-7-I phase transition at 298 K (Fig. 1b) can be explained by examining the crystal structure of CO2-adsorbed ZIF-7-I determined by ND under similar conditions18 (Fig. 3a). It can be found that once adsorbed, CO2 molecules bind to pore B through weak hydrogen bonding (OCO2···HB = 2.64(2) Å). Thus it is likely that CO2 only gets adsorbed in pore B at low temperature when the thermal motion of CO2 is significantly minimized. This conclusion is validated by comparing the CO2 self-diffusivity in ZIF-7 at 225 and 298 K. We used 225 K instead of 195 K in the measurement because of the detection limit. Since 195 K is the sublimation point of CO2 at 101 kPa, at this temperature CO2 diffusion is too slow to be measured accurately. Self-diffusion describes the elementary jumps of an individual gas molecule between adsorption sites. The low value of CO2 self-diffusivity measured at 225 K (1.5(8) × 10−11 m2 s−1, Fig. 2c) shows that CO2 molecules exhibit negligible jumping between adsorption sites at or below this temperature. This facilitates CO2 storage into pore B, which corresponds to the initial CO2 adsorption prior to the ZIF-7-II to ZIF-7-I phase transition at 195 K. In contrast, CO2 self-diffusivity measured at 298 K (1.9(2) × 10−10 m2 s−1, Fig. 2b) shows that CO2 exhibits rapid jumping between adsorption sites at this temperature, which indicates that CO2 has enough energy to overcome the stabilization provided by the weak hydrogen bonds between CO2 and pore B, leading to the absence of initial CO2 adsorption.

CO2 migration route and ZIF-7 structural dynamics. a Spatial relationship between pores A and B as well as adsorbed CO2, determined by ND. In general view, pore A: green, pore B: blue, star linker: yellow, CO2: red. The symmetry of CO2 has been disregarded for clarity. In top and side view, star linker: N, blue; C, green; H/D, pink. C of CO2 in pore A: yellow, C of CO2 in pore B: purple, O: red. b Star linker rotation caused by CO2 adsorption in pore B, leading to the ZIF-7-II to ZIF-7-I phase transition. c The channel between pores A and B in ZIF-7-II, allowing CO2 to migrate from pore B to A. pore A: green, pore B: blue, star linker: yellow

In order to corroborate the above hypothesis, grand canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC) molecular simulations were performed using ZIF-7-I and ZIF-7-II structures separately. A similar strategy was followed in the past on ZIF-713 and ZIF-827,28. Figure 4a shows the comparison of the experimental and simulated CO2 isotherms of ZIF-7. In the simulated isotherms, we highlighted those points (solid symbols) corresponding to the phases observed experimentally. At 298 K, the simulated isotherms match nicely the experimental data, with a slight overprediction at lower pressures for ZIF-7-II. At 195 K, the simulated isotherm for ZIF-7-II—with blocked pores A—matches the experimental isotherm very well. Figure 4b shows the snapshot and density distribution of adsorbed CO2 molecules in ZIF-7-II at 10 kPa and 195 K. These results confirm the initial CO2 adsorption in pore B of ZIF-7-II. Although CO2 uptake in ZIF-7-I after the phase transition is underpredicted by the GCMC simulations, the results match those from the previous simulations on ZIF-713. As indicated previously, more efficient packing of CO2 molecules may take place in ZIF-7-I at 195 K, which might be the reason for the underprediction by our GCMC simulations.

GCMC simulations. a CO2 adsorption isotherms of ZIF-7. Left: a comparison of experimental (gray circles) and simulated adsorption isotherms, using ZIF-7-I (triangles) and ZIF-7-II (squares) structures at 195 (orange) and 298 K (purple). Right: a detailed comparison at low pressure. Solid triangles and squares in the simulated isotherms correspond to the phases observed in the experimental isotherms. The vertical lines highlight the range of pressures at which the phase transitions occur: 10–30 kPa at 195 K and 40–60 kPa at 298 K. b Snapshot (left) and density distribution (right) of adsorbed CO2 molecules in ZIF-7-II at 10 kPa and 195 K. c Heat of adsorption of CO2 in ZIF-7-I (triangles) and ZIF-7-II (squares) at 195 (orange) and 298 K (purple). Red dotted lines are included as eye-guides

CO2 migration and ZIF-7 structural dynamics

At this point, it is clear that CO2 adsorption initially takes place in pore B. However, how CO2 migrates from pore B to pore A and what induces the ZIF-7-II to ZIF-7-I phase transition remains uncertain. The crystal structure of CO2-adsorbed ZIF-7-I determined by ND at 300 K is used to examine the interactions between CO2 molecules and both pores as well as the spatial relationship between them. Pores A and B share a common bIm linker and CO2 molecules adsorbed in both pores are stabilized by hydrogen bonding with this linker (Fig. 3a). This common linker is named the star linker for the convenience of explanation. The CO2 molecule in pore B has one hydrogen bond with the imidazole ring (Im) of the star linker. At the initial CO2 adsorption stage, as the number of CO2 molecules adsorbed in pore B increases, the hydrogen bond between CO2 and Im makes the star linker rotate in a way that eventually induces the ZIF-7-II to ZIF-7-I phase transition (Fig. 3b). Meanwhile, the migration of CO2 from pore B to pore A happens fast via the channel between two pores (Fig. 3c). The CO2 molecule is stabilized in pore A by two hydrogen bonds with the benzene ring (Bz) of the star linker. These two hydrogen bonds are stronger than (OCO2···HBz = 1.68(1) Å) or comparable with (OCO2···HBz = 2.86(1) Å) that between CO2 and Im in pore B (OCO2···HIm = 2.64(2) Å). Due to their spatial relationships, the hydrogen bond formed between CO2 and Bz in pore A inhibits star linker rotation caused by the hydrogen bond between CO2 and Im in pore B (Fig. 3a). Thus at this point, the ZIF-7-II to ZIF-7-I phase transition is completed. It is worth mentioning that, although there are two types of pore B in ZIF-7-II (Fig. 1d), type I pore B should be the one that is responsible for the initial CO2 adsorption. This is because its shared linker with pore A has the most distinctive rotation during the ZIF-7-II to ZIF-7-I phase transition, and is associated with the highest activation barrier for the phase transition. This is further confirmed by our inelastic neutron scattering (INS) study of the changes in the vibrational behavior of the linkers during CO2 adsorption. INS is a highly quantitative spectroscopic technique whose results are generally comparable to that of theoretical calculation. See Supplementary Discussion for detailed analysis (Supplementary Fig. 7 and Supplementary Table 4).

In order to further validate the CO2 migration route concluded from experimental data, we complemented our study with ab initio calculations based on density functional theory (DFT). Energetics were studied when CO2 molecules are adsorbed at different locations, including in pore B or in the channel between pores A and B before the ZIF-7-II to ZIF-7-I phase transition, as well as in pore A or in both A and B pores after phase transition (see Supplementary Fig. 8 for models). In each case, CO2 molecules are localized near the bIm linkers after energy relaxation. The averaged adsorption energy of each CO2 molecule (∆ECO2) is given by

where E, Ef, ECO2, and NCO2 are the total energy of the system, the framework energy, the energy of a single CO2 molecule, and the number of CO2 molecules, respectively. Before phase transition, the CO2 adsorption energy in pore B is only 6.9 kJ mol−1 per molecule larger than that in the channel between pores A and B. Such a small energy difference suggests that CO2 molecules are likely to stay in pore B initially but can easily move into the channel under thermal excitation. After phase transition, the CO2 adsorption energy in both A and B pores is 14.1 kJ mol−1 per molecule larger than that in pore A. This suggests that CO2 molecules tend to first fill pore B before going into pore A. The combined picture of these results is that in the adsorption process: CO2 molecules migrate from pore B to pore A via the open channel. This is in line with the conclusions we derived from experimental results.

It is noted that DFT calculations were carried out at 0 K, thus temperature effect (e.g., atomic vibrations) was not taken into account. GCMC simulations allow us to have a complete thermodynamic description of the CO2 interactions with ZIF-7 under experimental conditions. DFT calculations estimate that the energy difference between ZIF-7-I and ZIF-7-II framework (ΔEf) is around 29.9 kJ mol−1 (one unit cell). Upon adsorption, this energy difference is expected to be overcome by the affinity of CO2. Figure 4c shows the heat of adsorption (Qst) as a function of CO2 uptake, obtained from GCMC simulations. The difference in the heat of adsorption of CO2 (∆Qst) in the transition region can be given by12

where N′CO2 is the number of CO2 molecules adsorbed in one ZIF-7 unit cell, Qst-I and Qst-II are the Qst obtained for ZIF-7-I and ZIF-7-II, respectively. At 298 K, ∆Qst is 30.1 kJ mol−1 at the uptake of 1.3 mmol g−1 (NCO2 = 7) where the ZIF-7-II to ZIF-7-I phase transition completes. This value is comparable to ΔEf. At 195 K, maximum ∆Qst is 34.5 kJ mol−1 at the uptake of 2 mmol g−1 (NCO2 = 11), also comparable to ΔEf. These results underpin that initial adsorption is needed to compensate for the energy penalty of the structural transition. However, as the energy barrier of the structural transition is difficult to be estimated and CO2 uptake in ZIF-7-I at 195 K after the transition is underpredicted by the GCMC simulations, the simulated amount of CO2 needed to trigger the phase transition slightly deviates from the experimental value.

Discussion

In conclusion, a refined ZIF-7 CO2 adsorption mechanism is presented in this work. It reveals that the CO2-adsorption-stimulated structural flexibility of ZIF-7 is due to CO2 migration between its different guest-hosting pores upon pressure. This mechanism is extremely uncommon and is distinct from the majority of guest-host interactions reported for other MOFs. Overall, the relationship between guest and host dynamics discussed here provides new insights into MOF flexibility. This work also offers new methods for analyzing adsorption mechanisms in other known flexible MOFs, particularly those with non-uniform porous structures, by evaluating the adsorption strength in each type of pores and the extent of guest migration with respect to the phase change. This may lead to the selective filling of a specific type of pores without triggering the associated phase transformation, which could result in the rational design of optimized stimuli-responsive behaviors.

Methods

Synthesis

ZIF-7 was synthesized using a solvothermal method. 0.75 g of zinc nitrate hexahydrate (Zn(NO3)2·6H2O, 2.52 mmol) and 0.25 g of benzimidazole (HbIm, C7H6N2, 2.05 mmol) were first dissolved in 75 ml of fresh dimethylformamide (DMF). The resultant solution was then sealed into a 100 ml Teflon-lined stainless steel autoclave. The autoclave was heated at 400 K for 48 h. After naturally cooling to room temperature, white platy crystals were isolated after the mother liquor was removed. The solid product was washed thoroughly with methanol. The average yield was around 0.34 g (97% based on HbIm). All chemicals employed were commercially available (Sigma-Aldrich and Acros Organics), with purity of 98% or above, and were used as received.

Laboratory characterization

The crystal structures of ZIF-7 samples were characterized by powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) using a Bruker D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer operated at 40 kV and 40 mA with Cu Kα1 radiation (λ = 1.54056 Å) (Supplementary Fig. 9). The XRD data of the as-synthesized sample were compared with that calculated from the ZIF-7-I crystallographic model in the literature14. ZIF-7-I purity was around 100%. The morphology of ZIF-7 samples was examined by scanning electron microscopy using a JEOL JSM-5510 microscope (Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11). CO2 adsorption isotherms were measured by a Hiden Isochema IGA gravimetric analyzer. The as-synthesized sample was activated at 400 K in air for 48 h before each measurement. Before data collection, the sample was vacuumed in situ (~10−4 mbar) at room temperature for 3 h to remove any remaining trace guest molecules.

In situ synchrotron X-ray powder diffraction (SXRD)

In situ SXRD data were collected at beamline I11, Diamond Light Source, Harwell, UK. The energy of the incident X-ray was set at ~15 keV29. The wavelength (λ = 0.82634(1) Å) and the 2θ zero point were determined by fitting the diffraction data of high-quality silicon powder (SRM640c).

The as-synthesized sample was first activated at 400 K in air for 24 h. The activated sample was then loaded into a quartz glass capillary (0.5 mm). Glass wool was packed on top of the sample and the capillary was then fixed onto a custom-made gas cell. Before data collection, the sample cell was evacuated to 10−5 Pa at room temperature for 3 h to remove any remaining trace guest molecules from the sample. CO2 pressure was controlled by a custom-made gas loading system. After each CO2 loading, 2 min was allowed before data collection for the system to reach equilibrium.

Since sample spinning was prohibited due to the position of the gas cell, the sample was rocked through ± 10o about the ω-axis to improve powder averaging. SXRD data were collected with Mythen II position sensitive detectors (PSD) over the 2θ range of 2–90°, with two datasets offset by 0.25° (2θ) collected (each for 30 s). These datasets were subsequently automatically merged to remove gaps in the data where the microstrips (X-ray detection modules) join. PSD and data treatment have been described in detail in the literature30.

Quasi-elastic neutron scattering (QENS)

QENS data were collected using the IRIS indirect geometry time-of-flight (TOF) spectrometer at ISIS Neutron and Muon Source, Rutherford Appleton Laboratory, Harwell, UK. At IRIS, the sample first got a white beam of neutrons containing a band of energy. After scattering, the crystal analyzer (the (002) plane of pyrolithic graphite) chose a single final energy (1.84 meV) to send to detectors. Scattered neutrons were detected over an angular range of 2θ = 25–160°. The instrumental resolution and detector efficiencies were calibrated by fitting the spectrum of a vanadium standard. The elastic energy resolution was 17.5 μeV. The energy transfer range was −0.4–0.4 meV and the Q range was 0.42–1.85 Å−1. IRIS was also built with long-wavelength diffraction capability. The d range was 1–12 Å with Δd/d = 2.5 × 10−3.

The as-synthesized sample was first activated at 400 K in air for 24 h. The activated sample (ca. 4.6 g) was then wrapped into two pieces of aluminum foil to make a sample lining fitted into the annular space of an aluminum cylinder sample cell (∅ 24/28 mm × h 65.6 mm). The thickness of the sample lining was about 2 mm. Glass wool was placed in the top of the sample cell. The sample cell was then sealed with indium and connected to a custom-made gas loading system. During data collection, the temperature of the sample was controlled by a helium cryostat and thermocouples. QENS spectra were first recorded when the sample was under vacuum. At 15 and 225 K, the accumulated proton current was 600 μA for good statistics. At 298 K, the accumulated proton current was 1146.8 μA. CO2 was then loaded into the sample cell at 298 K to enable ZIF-7 to reach a CO2 uptake of 1.3 mmol g−1. For QENS data of the loaded sample collected at 15, 225, and 298 K, the accumulated proton current was 600 μA. Diffraction data were collected simultaneously with QENS data collection. CO2 loading was measured using the method employed in the literature31,32,33. It is also described in detail in Supplementary Methods.

Inelastic neutron scattering (INS)

INS data were collected using the TOSCA TOF spectrometer at ISIS Neutron and Muon Source, Rutherford Appleton Laboratory, Harwell, UK. TOSCA has a wide energy transfer range of −2.5–1000 meV (−20–8050 cm−1) and a high energy resolution of ca. 1.25% ΔE/E. The sample environment at TOSCA was similar to that at IRIS. Before data collection, the as-synthesized sample was first activated at 400 K in air for 24 h. The activated sample (ca. 4.6 g) was then wrapped into two pieces of aluminum foil to make a sample lining for a stainless steel cylinder sample cell (∅ 16 mm × h 76 mm). Glass wool was placed in the top of the sample cell to prevent any sample spillage during the experiment. The sample cell was then sealed with a copper O-ring and connected to a custom-made gas loading system. The sample chamber was evacuated to 10−5 Pa at room temperature for 16 h to remove any remaining trace guest molecules from the sample. During data collection, the temperature of the sample was controlled by a closed cycle refrigerator (CCR) and was kept below 10 K to minimize the thermal motion of the sample and CO2 molecules. INS spectra were first recorded when the sample was under vacuum. The accumulated proton current was 3604 μA for good statistics. CO2 was then loaded into the sample cell at 298 K to enable ZIF-7 to reach a CO2 uptake of 1.3 mmol g−1. CO2 loading was measured using the same method as that in the QENS experiment. During data collection of the loaded sample, the accumulated proton current was 3558.6 μA.

Density functional theory (DFT) calculation

Models for the DFT calculations were built based on the crystal structures from the literature18,19. One ZIF-7 unit cell was used with a chemical formula of Zn18C252N72H180. Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) generalized gradient approximation (GGA)34 implemented in the VASP package35 was used. The projector augmented wave (PAW)36 pseudopotential method was employed. Due to the large unit cell of ZIF-7, only Gamma point was sampled. The cutoff energy was 400 eV. The shape of the unit cell and atomic positions were allowed fully relaxed during the optimization. The energy convergence for the self-consistent electronic relaxation was set to be 10−6 eV and the force convergence was set to be 0.01 eV Å−1. To count in the weak dispersive interaction, van der Waals interactions (as implemented in the DFT-D2 scheme37,38) were considered during the calculations. We included a typical input file of our DFT calculations as a supporting file (Supplementary Data 1). Details of the calculation can be found in this file.

Grand canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC) molecular simulations

CO2 adsorption isotherms in ZIF-7 were investigated using grand canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC) simulations performed in the multi-purpose code RASPA39. ZIF-7-I and ZIF-7-II models were built based on the crystal structures from the literature18,19. Framework atoms were kept fixed at the crystallographic positions. In order to correctly describe the absence of CO2 molecules in pores A before the ZIF-7-II to ZIF-7-I phase transition, pores A were all blocked in ZIF-7-II during the simulation. We used the standard Lennard-Jones (LJ) 12-6 potential to model the interactions between the framework and fluid atoms. In addition, a Coulomb potential was used for fluid-fluid interactions. The parameters for framework atoms were derived from the Universal Force Field40 and those previously developed for ZIF-827. CO2 molecules were modeled using the TraPPE potential with charges placed on each atom and at the center of mass (Supplementary Table 5)41. EQeq was used to assign the partial charges of the framework. The Lorentz-Berthelot mixing rules were employed to calculate fluid-solid LJ parameters, and LJ interactions beyond 12.8 Å were neglected. The Ewald summations method was used to compute the electrostatic interactions. Up to 50,000 Monte Carlo cycles were performed, the first 50% of which were used for equilibration, and the remaining steps were used to calculate the ensemble averages. Monte Carlo moves consisted of insertions, deletions, displacements, and rotations. In a cycle, N Monte Carlo moves are attempted, where N is defined as the maximum of 20 or the number of adsorbates in the system. To calculate the gas-phase fugacity we used the Peng-Robinson equation of state42. The isosteric heat of adsorption (Qst) was calculated using the fluctuation theory43. Input files are included in Supplementary Data 2.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors on reasonable request. See author contributions for specific datasets.

References

Carrington, E. J. et al. Solvent-switchable continuous-breathing behaviour in a diamondoid metal-organic framework and its influence on CO2 versus CH4 selectivity. Nat. Chem. 9, 882–889 (2017).

Sato, H. et al. Self-accelerating CO sorption in a soft nanoporous crystal. Science 343, 167–170 (2014).

Horcajada, P. et al. Flexible porous metal-organic frameworks for a controlled drug delivery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 6774–6780 (2008).

Chen, Q. et al. A controllable gate effect in cobalt(II) organic frameworks by reversible structure transformations. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 11550–11553 (2013).

Yanai, N. et al. Gas detection by structural variations of fluorescent guest molecules in a flexible porous coordination polymer. Nat. Mater. 10, 787–793 (2011).

McDonald, T. M. et al. Cooperative insertion of CO2 in diamine-appended metal-organic frameworks. Nature 519, 303–308 (2015).

Chang, Z., Yang, D.-H., Xu, J., Hu, T.-L. & Bu, X.-H. Flexible metal-organic frameworks: recent advances and potential applications. Adv. Mater. 27, 5432–5441 (2015).

Schneemann, A. et al. Flexible metal-organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 6062–6096 (2014).

Murdock, C. R., Hughes, B. C., Lu, Z. & Jenkins, D. M. Approaches for synthesizing breathing MOFs by exploiting dimensional rigidity. Coord. Chem. Rev. 258–259, 119–136 (2014).

Serre, C. et al. Very large breathing effect in the first nanoporous chromium(III)-based solids: MIL-53 or CrIII(OH)·{O2C−C6H4−CO2}·{HO2C−C6H4−CO2H}x·H2Oy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 13519–13526 (2002).

Férey, G. et al. Hydrogen adsorption in the nanoporous metal-benzenedicarboxylate M(OH)(O2C–C6H4–CO2) (M=Al3+, Cr3+), MIL-53. Chem. Commun. 21, 2976–2977 (2003).

Krause, S. et al. A pressure-amplifying framework material with negative gas adsorption transitions. Nature 532, 348–352 (2016).

Du, Y. et al. New high- and low-temperature phase changes of ZIF-7: elucidation and prediction of the thermodynamics of transitions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 13603–13611 (2015).

Park, K. S. et al. Exceptional chemical and thermal stability of zeolitic imidazolate frameworks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 10186–10191 (2006).

Aguado, S. et al. Guest-induced gate-opening of a zeolite imidazolate framework. New J. Chem. 35, 546–550 (2011).

van den Bergh, J. et al. Understanding the anomalous alkane selectivity of ZIF-7 in the separation of light alkane/alkene mixtures. Chem. Eur. J. 17, 8832–8840 (2011).

Gücüyener, C., van den Bergh, J., Gascon, J. & Kapteijn, F. Ethane/ethene separation turned on its head: selective ethane adsorption on the metal-organic framework ZIF-7 through a gate-opening mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 17704–17706 (2010).

Zhao, P., Lampronti, G. I., Lloyd, G. O., Suard, E. & Redfern, S. A. T. Direct visualisation of carbon dioxide adsorption in gate-opening zeolitic imidazolate framework ZIF-7. J. Mater. Chem. A 2, 620–623 (2014).

Zhao, P. et al. Phase transitions in zeolitic imidazolate framework 7: the importance of framework flexibility and guest-induced instability. Chem. Mater. 26, 1767–1769 (2014).

Li, J.-R. et al. Carbon dioxide capture-related gas adsorption and separation in metal-organic frameworks. Coord. Chem. Rev. 255, 1791–1823 (2011).

Du, Y. et al. Insights into the Flexibility of ZIF-7 and Its Structural Impact in Alcohol Adsorption. J. Phys. Chem. C. 121, 28090–28095 (2017).

Cuadrado-Collados, C. et al. Understanding the breathing phenomena in nano-ZIF-7 upon gas adsorption. J. Mater. Chem. A 5, 20938–20946 (2017).

Chokbunpiam, T. et al. Gate opening effect for carbon dioxide in ZIF-8 by molecular dynamics – Confirmed, but at high CO2 pressure. Chem. Phys. Lett. 648, 178–181 (2016).

Chmelik, C., van Baten, J. & Krishna, R. Hindering effects in diffusion of CO2/CH4 mixtures in ZIF-8 crystals. J. Membr. Sci. 397–398, 87–91 (2012).

Pantatosaki, E. et al. On the impact of sorbent mobility on the sorbed phase equilibria and dynamics: A study of methane and carbon dioxide within the zeolite imidazolate framework-8. J. Phys. Chem. C. 116, 201–207 (2012).

Bux, H., Chmelik, C., van Baten, J. M., Krishna, R. & Caro, J. Novel MOF-membrane for molecular sieving predicted by IR-diffusion studies and molecular modeling. Adv. Mater. 22, 4741–4743 (2010).

Fairen-Jimenez, D. et al. Flexibility and swing effect on the adsorption of energy-related gases on ZIF-8: combined experimental and simulation study. Dalton. Trans. 41, 10752–10762 (2012).

Fairen-Jimenez, D. et al. Opening the gate: framework flexibility in ZIF-8 explored by experiments and simulations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 8900–8902 (2011).

Thompson, S. P. et al. Beamline I11 at Diamond: a new instrument for high resolution powder diffraction. Rev. Sci. Inst. 80, 075107–075109 (2009).

Thompson, S. P. et al. Fast X-ray powder diffraction on I11 at Diamond. J. Synchrotron Rad. 18, 637–648 (2011).

Lu, Z. et al. Modulating supramolecular binding of carbon dioxide in a redox-active porous metal-organic framework. Nat. Commun. 8, 14212 (2017).

Yang, S. et al. Supramolecular binding and separation of hydrocarbons within a functionalized porous metal-organic framework. Nat. Chem. 7, 121–129 (2014).

Yang, S. et al. Selectivity and direct visualization of carbon dioxide and sulfur dioxide in a decorated porous host. Nat. Chem. 4, 887–894 (2012).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmuller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmuller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Fang, H., Dove, M. T. & Refson, K. Ag–Ag dispersive interaction and physical properties of Ag3Co(CN)6. Phys. Rev. B 90, 054302 (2014).

Grimme, S. Semiempirical GGA-type density functional constructed with a long-range dispersion correction. J. Comput. Chem. 27, 1787–1799 (2006).

Dubbeldam, D., Calero, S., Ellis, D. E. & Snurr, R. Q. RASPA: molecular simulation software for adsorption and diffusion in flexible nanoporous materials. Mol. Simul. 42, 81–101 (2016).

Rappe, A. K., Casewit, C. J., Colwell, K. S., Goddard, W. A. & Skiff, W. M. UFF, a full periodic table force field for molecular mechanics and molecular dynamics simulations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 114, 10024–10035 (1992).

Potoff, J. J. & Siepmann, J. I. Vapor–liquid equilibria of mixtures containing alkanes, carbon dioxide, and nitrogen. AIChE J. 47, 1676–1682 (2001).

Reid, R. C., Prausnitz, J. M. & Poling, B. E. The properties of gases and liquids. (McGraw Hill Book Co., New York, USA, 1987).

Nicholson, D. & Parsonage, N. G. Computer Simulation and the Statistical Mechanics of Adsorption. (Academic Press, New York, USA, 1982).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Cambridge Commonwealth, European and International Trust, and UK Science and Technology Facilities Council. The authors thank Diamond Light Source (UK) for the SXRD facility and ISIS Neutron and Muon Source (UK) for QENS and INS facilities. Dr. James Taylor from ISIS Neutron and Muon Source is thanked for his assistance in CO2 adsorption isotherm measurements. Dr. Giulio I. Lampronti from the University of Cambridge is acknowledged for discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.Z. carried out material synthesis and laboratory characterization. In situ SXRD was performed by P.Z. and C.C.T. QENS data were collected by P.Z., S.M., and S.A.T.R. INS data were collected by P.Z., and S.R. H.F. performed the DFT calculations. A.L. carried out the GCMC simulations, supervised by D.F.-J. The manuscript was written and revised by P.Z. H.F., I.J.M., S.C.E.T., and S.A.T.R. The project was planned and directed by P.Z. and supervised by S.A.T.R. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Journal peer review information: Nature Communications thanks Yi Du, Claire Hobday and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, P., Fang, H., Mukhopadhyay, S. et al. Structural dynamics of a metal–organic framework induced by CO2 migration in its non-uniform porous structure. Nat Commun 10, 999 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-08939-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-08939-y

This article is cited by

-

Mixed-linker strategy for suppressing structural flexibility of metal-organic framework membranes for gas separation

Communications Chemistry (2023)

-

Large breathing effect in ZIF-65(Zn) with expansion and contraction of the SOD cage

Nature Communications (2022)

-

MOFs in the time domain

Nature Reviews Chemistry (2021)

-

Heterogeneous AgPd Alloy Nanocatalyst for Selective Reduction of Aromatic Nitro Compounds Using Formic Acid as Hydrogen Source

Catalysis Letters (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.