Abstract

Transition metal dichalcogenide (TMD) quantum dots (QDs) are fundamentally interesting because of the stronger quantum size effect with decreased lateral dimensions relative to their larger 2D nanosheet counterparts. However, the preparation of a wide range of TMD QDs is still a continual challenge. Here we demonstrate a bottom-up strategy utilizing TM oxides or chlorides and chalcogen precursors to synthesize a small library of TMD QDs (MoS2, WS2, RuS2, MoTe2, MoSe2, WSe2 and RuSe2). The reaction reaches equilibrium almost instantaneously (~10–20 s) with mild aqueous and room temperature conditions. Tunable defect engineering can be achieved within the same reactions by deviating the precursors’ reaction stoichiometries from their fixed molecular stoichiometries. Using MoS2 QDs for proof-of-concept biomedical applications, we show that increasing sulfur defects enhanced oxidative stress generation, through the photodynamic effect, in cancer cells. This facile strategy will motivate future design of TMDs nanomaterials utilizing defect engineering for biomedical applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Two-dimensional (2D) transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) with comparable structures to graphene, have attracted tremendous attention during the past few years. This large family of layered materials shared a common molecular formula and general structure where each member consists of mono-atomic thick stacked layers of repetitive covalently bonded X–M–X (M = Transition metal; X = Chalcogen). With decreasing number of layers, TMDs nanosheets transit from an indirect gap to a direct band-gap semi-conductor (e.g., 1.2–1.9 eV for MoS2 from bulk form to monolayer)1,2. This special layers-dependent physical property inspired 2D TMDs nanosheets-enabled applications in biomedicine3,4, sensors5, transistors6, catalysts7,8, photodetectors9, and energy storage devices10,11. Further reduction of the lateral size of TMDs few-layers or mono-layer nanosheets to quantum dots (QDs) or 0D nanodots further accentuate their electrical/optical properties due to a stronger quantum confinement and edge effects12. This enhancement introduced more dimensions of interesting and exploitable properties for catalytic and biomedical applications13,14, of which the latter is gravely under-represented. This could be due to the harsh and non-biocompatible methods in robust synthesis of many of the TMD QDs.

Atomic defects in transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) nanomaterials add an additional dimension to its optical, chemical and electronic activities. Top-down approaches like laser, plasma and electron bombardment have been intensively used to introduce defects on TMDs nanosheets and thereby controlling their optical and electrical properties. Moreover, the methods are usually single sheet process, albeit with great precision but at the expense of low scalability and high cost. Applying the same top–down approaches to reliably engineer defects in TMD QDs is extremely difficult due to the minute size of the QDs. This lack of defect engineering option has further curtailed TMD QDs’ potential.

In the past few years, many strategies, including lithium intercalation and exfoliation have been developed for synthesizing 2D TMD nanosheets15,16,17, but mild and general synthesis methods for 0D TMDs QDs are few. Top-down synthesis methods through a combination of grinding and sonication techniques, could obtain 1T-phase TMD QDs11,12. Although much progress has been achieved, to date, many more problems remain that needed solving before exploring their unique properties for catalytic and biomedical-based application. The top-down production of high quality TMD QDs has so far been extremely challenging because of the high degree of size and layers reduction required resulting in a low yield of production at the end of a long tedious process18,19, which involve time-consuming exfoliation and ultrasonication processes starting from bulk TMD crystals, exfoliated first to 2D TMD nanosheets and then further cutting them down to TMD QDs sizes. Fastidious post-treatment processes (for example, gradient centrifugation) is required; further reducing the yields of each sized TMDs QDs. Reports on bottom-up strategies for TMD QDs are generally limited to harsh hydrothermal methods (200 oC and at least 24 h)20,21,22. Further defect engineering of as-synthesized TMD QDs will therefore allow for more property explorations of TMD QDs for catalytic, semi-conducting and biomedical applications.

Here we demonstrate a facile and possibly universal bottom-up route to synthesize MoS2 QDs with different degrees of defect under a fair degree of control. All the MoS2 QDs synthesized under our mild aqueous condition are of uniform sizes of around 3.9 nm. This synthesis method has been further expanded to successfully prepare a library of various other TMD QDs. We also showed, using MoS2 QDs, its potential as a photodynamic agent that is easily tunable through bottom-up disordering engineering. Previous studies have alluded to the possibility of defects in semiconductor QDs matter to photodynamic effect but that was never proven23, possibly due to the difficulty in controllable engineering defects in semiconductor QDs. In this paper, different degrees of defect engineering were achieved in 0D TMDs QDs via bottom-up stoichiometry deviations. With this defect-variable TMD QDs, the suspected correlation between defect degree and photodynamic properties is verified. The possible mechanism of defect enhanced reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation was proposed. By bottom-up defect engineering of TMD QDs, we showed that we could tune photodynamic oxidative stress effect on cancer cells.

Results

Characterization of as synthesized MoS2 QDs

The MoS2 QDs were prepared by a bottom-up route conducted in aqueous condition at room temperature via a simple chemical reaction starting with Na2S and MoCl3, MoCl5 or MoO3. Inspired by biomineralization, natural biopolymers such as BSA were used as surfactant because of their template effect and excellent biocompatibility24,25. Briefly, pH value of Mo-precursor solution was firstly adjusted to be above 11. In this high pH solution, the molybdenum precursors—MoCl5 or MoO3 decompose, yielding stable MoO42-(Supplementary Figure 1). The reaction scheme can be expressed as:

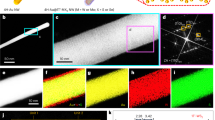

Then they were transferred into BSA solution; Na2S solution was introduced into the mixture. Subsequent adjusting of pH value to 6 with addition of HCl activates the sulfur precursors, initiating the reaction between MoO42− and sulfur precursors protected by BSA (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Movie 1). Our one-pot reaction was carried out under mild experimental conditions in the laboratory; without the need for high temperature and pressure or special apparatus26. Our method is easily scalable. The aqueous product showed a faint yellow color with good dispersibility (Fig. 1b). The transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images showed a consistent size quality of the as synthesized MoS2 QDs to be ~3.9 nm (Fig. 1c). The observed d-spacing (0.27 nm) is assigned to the (100) atomic plane of MoS2, confirming the high crystallinity of the MoS2 QDs (Fig. 1d). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was also performed to measure the composition and the corresponding chemical valence of the elements in MoS2 QDs (Supplementary Figure 2). Typical Mo4+ 3d3/2 peaks of 232.8 eV and Mo4+ 3d5/2 peaks of 229.6 eV could be clearly observed from the XPS spectrum (Supplementary Figure 2a), which suggested the presence of Mo (IV) of MoS2 QDs27. Supplementary Figure 2b shows the binding energy of sulfur with the S 2p3/2 and S 2p1/2 peaks at 162.15 eV and 163.05 eV, which is consistent with −2 oxidation state of sulfur. The atomic ratio of Mo to sulfur was quantified to be 1: 2.31. The higher sulfur content compared to the initial feed ratio (Mo: S = 1:2) might be due to the presence of S- containing cysteines in BSA on the surface of MoS2 QDs. The structure of MoS2 QDs was further characterized by powder X-Ray diffractometry (XRD, Fig. 1e). The XRD pattern of MoS2 QDs shows broad diffraction peaks, which is in accordance with the XRD features of low-dimensional nanoparticles, suggesting the small grain sizes of the MoS2 QDs. The main peaks at 11o, 29o and 36o can be assigned to the characteristic (001), (100) and (103) planes of hexagonal 2H-MoS2 (JCPDS NO. 24-0513). The colloidal suspension of MoS2 QDs prepared was very stable, with no obvious aggregations over at least 3 months (Supplementary Figure 3). This high stability property is an important advantage in biomedical applications. In comparison to 2D MoS2 nanosheets with relatively large lateral dimensions, four distinct excitonic peaks from 2D MoS2 nanosheets (A, B, C and D) were absent in the optical spectrum of MoS2 QDs (Fig. 1f), along with strongly absorption blue-shifted towards shorter wavelengths. These optical features should result from the stronger quantum size effect of MoS2 QDs with decreased lateral dimensions relative to 2D MoS2 nanosheets (Supplementary Figure 4). Noticeably, MoS2 QDs exhibited a new absorption peak at around 310 nm. Similar absorption features were also observed by others28,29; attributed to their quantum confinement effect. Here the as-prepared MoS2 QDs had an average diameter of 3.9 nm, which is close to the bulk Bohr exciton diameter of ~4 nm30. The discretized bands induced by quantum confinement allowed transitions from the deep valance band to the conduction band, increasing the discrete absorption bands of MoS2 QDs. By using the method based on the relation of (αћν)2 versus ћν (α is absorbance, ћ is the Planck’s constant and ν is frequency), the optical band gap of our MoS2 QDs was calculated to be ~3.45 eV, which is higher than that of bulk and single-layer MoS2 (1.2–1.9 eV). The quantum confinement effect and surface states (like surface defects) induced by the bottom-up method in MoS2 QDs may have collectively contributed to this band gap. With the presence of localized defect states, the surface states can narrow the calculated optical band gap through generating band-tailing effects31,32,33.

Benign aqueous room temperature bottom-up synthesis of MoS2 QDs. a Preparation of MoS2 QDs with bottom-up strategy. b Easy and scalable aqueous MoS2 colloidal suspension. Synthesis step takes less than 10–20 s (also refer to Supplementary Movie 1). c Ultrasmall but consistent as-synthesized MoS2 QDs. Inset: Distribution of MoS2 QDs size measured (ImageJ, n = 200). Scale bar: 100 nm. d HRTEM (Scale bar: 5 nm), e XRD and f UV-vis absorption spectra of MoS2 QDs showing a distinctively different nanomaterial from exfoliated MoS2 nanosheets

Surfactant effect on quality of MoS2 QDs

The hydrodynamic diameter of MoS2 QDs was determined to be 13 nm by dynamic light scattering (DLS), which was slightly larger than that of BSA (10 nm) and significantly higher than the TEM size of ~3.9 nm (Fig. 2a). One

Surfactant effect on quality of MoS2 QDs. a Size of the BSA and MoS2 QDs determined by DLS. b Schematic illustration of possible BSA interactions with one MoS2 QD. c TEM images of MoS2 QDs synthesized with BSA, Cys, Glu and Poly-Arg. Scale bar: 200 nm. d Statistical analysis of the size distributions of MoS2 QDs synthesized with different biological surfactants. e Binding energy of major functional groups of BSA to MoS2 QDs

MoS2 QD is likely to be interacting with one BSA molecule (Fig. 2b). The estimation value from thermogravimetric analysis was slightly larger than the DLS result (Supplementary Figure 5). With BSA as template to confine the growth of MoS2 QDs, the biomineralization process allow good size quality control. To investigate the role that the surfactant plays in the quality of MoS2 QDs, we also tested gluconate (Glu), poly-arginine (Poly-Arg) and cysteine (Cys) in the direct synthesis method. These biomolecules were selected as they provide the representative functional groups of BSA respectively: in Glu (–COOH), in Poly-Arg (–NH2), in Cys (–SH, –COOH, –NH2). Figure 2c suggests that all of above surfactants could mediate the successful synthesis of MoS2 QDs, while particle quality is highly dependent on the surfactant of choice. To quantify the particle size distribution, full width at half maximum (FWHM) was counted by analyzing the poly-distribution of MoS2 QDs from different surfactants. The size distribution and poly-distribution were analyzed from TEM samples with over 200 particles (with ImageJ). The statistical FWHM values of MoS2 QDs from BSA, Cys, Glu and Poly-Arg were 1.8, 3.1, 5.8 and 7.2, with the mean sizes of 3.9, 7.4, 7.3 and 9 nm, respectively (Fig. 2d), suggestive that BSA was more favorable for smaller QDs size and size distribution control. This also ruled out the sole fine size control of –COOH, –NH2 and –SH groups alone. Previous research suggested that disulfide bonds might possess much stronger binding energy to 2D MoS2 compared to single thiol34,35. To check that possibility in our MoS2 QDs, first-principle calculation was carried out to verify the binding affinity of the major functional groups of BSA to MoS2 QDs. As shown in Fig. 2e, benzene rings and disulfide exhibited much higher binding energy to MoS2 QDs compared to –SH, –COOH, –SH, –NH2 and –OH groups, which is 1.3 eV and 0.84 eV with respect to that of other groups (0.46 eV for –SH, 0.45 eV for –NH2 and 0.51 eV for –COOH) (Supplementary Table 1). These simulation results were consistent with the statistic FWHM values from TEM images (Fig. 2c), indicating that benzene rings and disulfide bonds may provide stronger affinity to stabilize QDs against aggregation and confine them for homogeneous growth, thus encouraging overall seeding and growth process in our case. To get direct experimental evidence that disulfide bonds does make a significant difference in the synthesis of MoS2 QDs, disulfide bridges of BSA was first reduced with NaBH4 to sulfhydryl groups. These denatured BSA (dBSA) with thiol groups were then used to prepare MoS2 QDs as per our synthesis protocol. The size of the as-acquired MoS2 QDs using dBSA exhibited a significant increase from 3.9 nm to a mean size of 6.3 nm (Supplementary Figure 6). This result was similar to Cys mediated samples which are laden with thiol groups, verifying the significant effect of disulfide bonds on the fine size distribution control of MoS2 QDs. The effect of benzene rings was also tested by using 2, 5 dihydroxybenzoic acid (DBA) as a stabilizer to synthesize MoS2-DBA. However, compared with other surfactants, the morphology of MoS2-DBA QDs was less controllable with the FWHM value to be 13.4 (Supplementary Figure 7), possibly due to the strong van der Waals interactions between benzene rings and weak ions-benzene ring interactions in the seeding stage of the particle formation. From these results we can conclude that the optimal surfactant for synthesizing MoS2 QDs are molecules containing disulfide bonds such as BSA.

The formation of MoS2 QDs was very fast at relatively low energy, as observed by TEM images sampled at different reaction time points and synthesis temperature (Supplementary Figure 8 and 9). The acquired MoS2 QDs could be easily purified by the addition of Cu2+ solution to precipitate out the MoS2 QDs, followed by centrifugation and dialysis to remove the supernatant and ions36 (Supplementary Figure 10), thus avoiding the fussy and time-consuming post-treatment process.

Expansion of this synthetic strategy to other TMD QDs

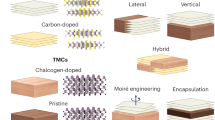

We expanded this facile and mild bottom-up method to prepare a variety of TMD QDs based on the straightforward chemical

reaction between chalcogen precursor and transition metal salt such as metallic oxide or metallic chloride (Fig. 3a), which may be applied to synthesize various TMD QDs (Fig. 3b). To validate the feasibility of this method, BSA was applied as the surfactant for the proof-of-concept verification. Different transition metal sources (for example Mo, W and Ru) and chalcogenide source (S, Se and Te) were mixed with BSA at the pH value of 11. As suggested in Fig. 4, after pH value was adjust to 6 ~ 7. WS2, RuS2, MoTe2, MoSe2, WSe2 and RuSe2 were successfully prepared. The TEM clearly illustrated their highly homogeneous of size distribution with majority of the diameters to be below 10 nm. The corresponding images of different TMD QDs suspensions in H2O showed good dispersibility. Because of different bandgaps and sizes, the prepared TMD QDs library showed different colors in aqueous solution and exhibited correspondingly different UV-Vis

Illustration of the bottom-up synthesis of TMD QDs under mild condition. a In this study, only the synthesis of commonly reported TMDs (MoS2, WS2, RuS2, MoTe2, MoSe2, WSe2 and RuSe2) QDs were showed. b Extrapolating the synthesis method to other TMD QDs synthesis may present an universal method to synthesis the various TMDs QDs

absorption spectra (Supplementary Figure 11). It is worth noting that some rod-like shape can also be found in the TEM images of MoTe2 samples, possibly due to high reactivity and instability of MoTe2 compounds compared to MoS2 /MoSe2 compounds37.

Stoichiometry and characterization

As our approach is bottom-up, the relative molarity of the reagents can be varied to be different from their stoichiometric ratios, enabling defect creation or dopant incorporation38. This theoretically allowed us to engineer defects in the as-synthesized TMD QDs from the bottom-up manner, thus providing a window of opportunity to tune their optical and electrical properties at the synthesis stage. Using MoS2 QDs as an example, three Mo/S relative molar concentrations, (4:2, 4:4 and 4:8) were pre-determined and reacted. Their respective products were named as MoS2-DH, MoS2-DM and MoS2-DL respectively. As shown in Fig. 5a, with increasing sulfur amount, the sample color changed from pale yellow for MoS2-DH to yellow and orange for MoS2-DM and MoS2-DL, respectively. Careful size analysis from TEM images (~200 particles counted) from the three groups indicated that varying initial relative concentration of reagents did not change the size distributions of the as-synthesized MoS2 QDs. Three MoS2 QDs groups exhibited similar size distributions with the average diameter of around 3.9 nm (Fig. 5b). The HRTEM images showed obvious discontinuities on the lattice planes such as dislocations and distortions were observed in the groups with the off-stoichiometric MoS2 S mole ratios like MoS2-DH and MoS2-DM QDs group (Fig. 5b). This discontinuity of the local lattice was thought to be caused by defects within crystals39. In MoS2-DH HRTEM images, several lattice planes with more discontinuities presented in the MoS2 structures, suggesting the strongly disordered

Engineering sulfur defects into MoS2 QDs through stoichiometric reaction control. a Adjusting precursor ratios produces three kinds of MoS2 suspension in pure water. TEM images show narrow size distribution. Scale bar: 50 nm. b Different stoichiometry does not affect overall size of QD MoS2. (Distributions derived from at least n = 200). HRTEM images show dislocations and distortions of lattice planes in MoS2 QDs due to intrinsic defects. Scale bar: 2 nm. c XRD show gradually enlarged lattice constants with decreasing stoichiometry in three MoS2 QDs. d PL spectrum show different emission intensities of the three MoS2 QDs at the same optical absorption. e XPS reveal the defect engineering was in the form of MoOxS2-x by the substitution of oxygen for sulfur. f Structural model of the reaction pathway of MoS2 QDs and defect engineering in MoS2 QDs as a function of precursor stoichiometry

arrangement of nanodomains in MoS2-DH samples (Fig. 5b). When the sulfur amount increases approaching stoichiometric MoS2, relatively perfect single crystals without disorder were observed, suggesting the relatively fewer defects in MoS2-DL. (Fig. 5b) The XRD diffraction peaks in three samples were broadening, confirming the nanoscale of these crystallites in different dimensions (Fig. 5c). A slight shift of major diffraction peaks indexed to (100) and (103) toward lower angles could also be observed from MoS2-DH to MoS2-DL samples, indicating the gradually enlarged lattice constants with increasing sulfur amounts and the homogeneous phase structures of all three MoS2 QDs groups. The stoichiometry related surface states were also investigated by studying the PL behavior of three MoS2 QDs. All three defect states exhibited excitation-dependent PL behaviors (Supplementary Figure 12). Their representative PL spectrum, with each emission spectrum were normalized to their solution optical absorbance density at the PL excitation wavelength of 400 nm (Fig. 5d). Such normalization was used to highlight the PL intensity change. By integrating the respective peak areas, we observed that the quantum yield (QY) of MoS2-DH (least sulfur content) possess the highest QY, which is approximately 1.79 times more than that of MoS2-DM (medium sulfur content) and 2.42 times higher than that of MoS2-DL. Previous reports suggested that the surface state of nanomaterial is similar to a molecular state. Both the surface state (such as defects) and intrinsic state (quantum size effect) of nanomaterial contribute to the complexity of excited states of QDs40,41. The TEM analysis of the lattice planes disorder appears to point to MoS2-DH as having the greatest degree of defects (Fig. 5). Interestingly, we observed a trend that with more defects, the photoluminescence quantum yield also increased. Moreover, the MoS2 QDs show two emission peaks with one at around 463–478 nm and the other one located at 530 nm, which could be attributed to intrinsic state emission (electron-hole recombination) and defect state emission, respectively29. In general, both intrinsic and defect state emissions influence the fluorescence spectrum. The red shift of fluorescence peaks from 463 nm of MoS2-DL to 469 nm for MoS2-DM and 478 nm for MoS2-DH can be observed and possibly due to the gradually increasing defects from MoS2-DL to MoS2-DH.

The controversy of whether defect sites and photoluminescence quantum yields are positively or negatively correlated is still ongoing. The influences of surface defects on photoluminescence quantum yields in smaller sized MoS2 quantum dots is still largely unknown. From our observations, the intrinsic state emission of the highest to lowest defect sites groups, MoS2-DH to MoS2-DL QDs still play the leading role in the PL emission and especially showed significantly higher efficiency in MoS2-DH QDs. One of the possible explanation is the passivation effect from oxygen atoms in the MoS2 crystal lattice. In the presence of oxygen, the PL of CdSe QDs could be enhanced by as much as a factor of 6, resulting from the surface passivation by oxygen on nanocrystalline surfaces42. This phenomenon of oxygen atoms induced surface passivation of QDs has also been identified in many other semiconductor QDs43,44. The embedded oxygen atoms in the crystalline of MoS2 structures, presumably played two roles; first by creating sulfur distortion defects which support defect state emission, second by forming Mo–S–O bond on the crystalline surface, which passivate it thus enabling the intrinsic state emission enhancement. Preliminary experiment on the sulfur defect (in the form of Mo–O) reveal that the defect could increase PL intensity. However, substantial work such as ultrafast dynamics studies can to explore these photophysics of MoS2 QDs in greater detail.

To obtain more information about the intrinsic changes of surface states, high-resolution XPS can reveal the surface chemical environment of the MoS2 samples. Figure 5e shows two characteristic peaks located at ~ 229.6 and ~232.8 eV in three spectrums, which arose from the Mo4+ 3d5/2 and Mo4+ 3d3/2, suggesting the dominance of Mo (IV) in the MoS2 samples. Compared with MoS2-DL, samples with less sulfur amount show significantly broadened peaks from MoS2-DM to MoS2-DH, confirming a higher degree of disorder in MoS2-DH45. In addition, both Mo4+ 3d5/2 and Mo4+ 3d3/2 doublet peaks in three samples shifted to lower binding energies with increasing sulfur amount, reflecting the reduction of MoS2. This behavior was consistent with decreasing intensity of Mo6+ peaks at ~236.2 eV, suggesting the presence of Mo–O bonds in MoS2-DH decreased when sulfur amount approach to stoichiometric MoS2. These results indicate that the defect engineering was in the form of MoOxS2-x, by the substitution of oxygen for sulfur within the MoS2 lattices. This is also consistent with the XRD patterns that the substitution of the smaller O atom by the significantly larger S atom in the lattices induce the enlarged lattice constants (Fig. 5c). XPS quantification of the chemical compositions further revealed the atomic ratio of Mo to S varied from 1:1.8 to 1: 2.34 (Supplementary Figure 13). So as sulfur amount increases (MoS2-DH group to MoS2-DL group) resulted in the decreasing amount of oxygen atom in MoOxS2−x, giving the direct evidence of sulfur amount-dependent degree of defects in MoS2 QDs.

Collectively the combined studies above, the reaction pathway of MoS2 QDs can be revealed and the defective crystal structures have been proved to obtain via a MoO42− + S2− → MoOxS2−x pathway (Fig. 5f). The relatively lower sulfur amount was critically responsible for engineering the MoS2 QDs with S defects. With lower sulfur amount, the reaction became more insufficient, residual Mo−O bonds (originally from MoO42-) that remained embedded within the otherwise crystalline MoS2 structure; thus creating distortion defects in the observed structure. This reaction behavior is similar to previous observation of controlling synthesis temperature in preparing defective 2D MoS2 nanosheets39. Here, 0D MoS2 QDs with controllable defect engineering were realized by simply tuning the synthesis reagent stoichiometry at room temperature.

Surface vacancy associated singlet oxygen generation

While the influence of defects on 2D TMDs have been largely studied for tuning optical and physical properties, which widely lead to excellent electronic applications, until now the defect effect on TMDs QDs are suggestive and speculative based on extrapolation from 2D TMDs observations and not applied directly in engineerable defects driven bioapplications. In addition, compared to 2D materials, 0D nanomaterials were supposed to exhibit better biological behavior than their 2D counterparts46,47. Thus photochemical related 1O2 generation capacity towards cancer therapy was investigated using our defect tunable MoS2 QDs. The singlet oxygen generation of the MoS2 was examined using 9, 10-anthracenediyl-bis(methylene) dimalonic acid (ABDA) as probe. It was found that without light irradiation, the absorbance of ABDA in three MoS2 QDs solution showed negligible decrease (Supplementary Figure 14). Under the white light irradiation, the absorption intensities within the groups decreased gradually with increased irradiation time (Fig. 6a). In addition, under the same irradiation condition without the presence of MoS2 QDs, both 1H-NMR and HPLC results did not show any appreciable change in the spectra of ABDA (Supplementary Figure 15), indicating the degradation of ABDA was indeed induced by the photosensitization from MoS2 QDs. The product of the ABDA trap after MoS2 QDs irradiation was checked by 1H- NMR and compared with the corresponding product of Rose Bengal (RB), a positive control known to generate 1O2 under irradiation. Similar chemical shifts were also observed in the corresponding H peaks of the products after irradiation (Supplementary Figure 16), suggesting that the species generated from MoS2 QDs and RB irradiation reacted with ABDA and produced similar ABDA products. We checked again with repeating the irradiation of MoS2-ABDA reaction in D2O or H2O conditions. It was found that there was higher depletion of the ABDA substrate when using D2O while irradiating MoS2 QDs (Supplementary Figure 17). This showed that 1O2 was generated from irradiation of MoS2 QDs. We further checked with a 1O2 2, 2, 6, 6-tetramethylpiperidine (TEMP) sensor-electron spin resonance spectrum (ESR) assay. We found more product after 5 min of MoS2 irradiation (Supplementary Figure 18). Collectively, 1O2 was likely generated after MoS2 irradiation.

Positive correlation between sulfur defects and photodynamic efficiency in QDs. a Absorption spectra of three kinds of MoS2 QDs in the presence of ABDA under light irradiation (0.1 W cm-2, 8 min). b Typical decomposition rate of the photosensitizing process, where A0 is the absorbance of initial absorbance of ABDA and A is the absorbance of ABDA under light irradiation at different time points (Full data plots can be found as Supplementary Figure 19). c Relative 1O2 quantum yield of two MoS2 QDs groups relative to MoS2-DL QDs. Mean ± SD, n = 4, Student’s t-test, p* < 0.05. d Detection of ROS generation at cellular level in colon cancer cell line, SW480 by intracellular ROS indicator H2DCFH-DA. Scale bar: 50 μm. e Structure illustration for the substitution of oxygen for sulfur within MoS2 lattices. f Calculated density of states of MoS2 QDs show the defects reduce the bandgap. g More sulfur defects induce stronger binding affinity of 3O2 to MoS2. h Proposed defect related 1O2 generation mechanism of MoS2 QDs

To compare the 1O2 quantum yield of three MoS2 QDs upon light irradiation, calculation was performed based on the photochemical methods reported before48,49,50. The decreased OD at 400 nm (OD400) was performed to determine the decomposition rate constants of the photosensitizing process of three MoS2 QDs, which was obtained by fitting the various OD400 curves (Fig. 6b). By further integrating the optical absorption of MoS2 QDs in the range 400–800 nm, the 1O2 quantum yield of two kinds of MoS2 QDs relative to MoS2-DL were determined. The MoS2-DH and MoS2-DM groups respectively exhibited 1O2 quantum yield of approximately 2.3 times and 1.7 times of MoS2-DL QDs’ quantum yield (Fig. 6c, Supplementary Figure 19). Physical quenching between 1O2 and N’s lone pair electrons of amines may exist; especially those aromatic amines of the BSA-surfactant51. It is therefore important to check that the differences in 1O2 quantum yield is not due to different amounts of BSA that are on the surface of the three kinds of MoS2 QDs. We quantified the amount of BSA on the surface of the three kinds of MoS2 using the micro-BCA protein assay. The BCA protein based assay showed no significantly different amounts of BSA on the same amount of the three MoS2 QDs defect types (Supplementary Figure 20). This indicated that the physical quenching due to proteins on the surface of the three MoS2 QDs groups are similar. Thus, confirming that the significant increase in the 1O2 quantum yields of MoS2-DM and MoS2-DH over MoS2-DL is due to increasing defects.

To further prove the correlations between the degree of defects and photodynamic efficiency, the ROS generation capacity was further detected inside the cancer cells by using dye dichlorohydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) as an intracellular ROS indicator. DCFH-DA is non-fluorescent but can be oxidized by ROS to yield highly fluorescent-dichlorofluorescein (DCF). As shown in Fig. 6d, after irradiation, strongest green fluorescence was observed in MoS2-DH incubated groups, with relatively lower green fluorescence in MoS2-DM groups and the lowest green fluorescence in MoS2-DL, which clearly confirmed the positive correlation between the degree of defects of MoS2 QDs and ROS generation capacity.

QDs acting as photosensitizers used in photodynamic therapy have attracted great attention in the area of nanomedicine52,53,54,55,56,57. In a typical photosensitizing process, the photosensitizer absorbs a quantum of light from ground state (S0) to the excited singlet state (S1), which is further converted to the excited triplet state (T1) via intersystem crossing (ISC). The subsequent energy transferring from T1 to triplet oxygen (3O2) result in the formation of singlet oxygen (1O2)58. The quantum yield of 1O2 generated by photosensitizers can be expressed as equation (1)59

where ФT is the quantum yield of T1 formation and ϕen is the efficiency of energy transfer from T1 to 3O2. To understand the enhanced ROS generation mechanism in cells, we analyzed the relationship between the defects and corresponding ROS generation behavior in MoS2 QDs. Previous records have confirmed that ФT is determinate by the ISC rate constants kISC, which could be estimated from Eq. (2)60

Here HSO represents the Hamiltonian for the spin-orbit perturbations and \(\Delta E_{\rm S1 - T1}\)(\(\Delta E_{\rm ST}\)) is the energy gap between S1 and T1. Therefore by engineering the HOMO-LUMO energy level in molecules to reduce the energy gap Δ\(E_{\rm ST}\), high photosensitizing efficiency could be achieved61,62. In our MoS2 QDs experiments, we speculated that the sulfur vacancy derived defects engineered the bandgap of MoS2 QDs, thus modulating the \(\Delta E_{\rm ST}\) to affect the photosensitizing capacity. To clarify this hypothesis, theoretical simulation using DFT was performed to check the density of states (DOS) of MoS2 QDs. After constructing a 3 × 3 × 1 supercell structure, zero, one and two sulfur atoms in the supercell were removed and substituted by oxygen atoms (Fig. 6e). This leads to different degrees of sulfur defects in MoS2, which denoted as pristine MoS2, MoS2-1D0 and MoS2-2D0. The calculated DOS in Fig. 6f demonstrated that the vacancies of sulfur atoms and the substitution of oxygen atoms act as n-type dopants. The more substitution of more electronegative oxygen atoms led to more charge carriers, with narrower bandgap from pristine MoS2 of 1.68 eV to 1.42 eV (MoS2-1D0) and 1.30 eV (MoS2−2D0). This decreasing bandgap of the simulated defective mode in MoS2 QDs qualitatively agrees with experimental observations from optical band gap (Supplementary Figure 21). Our calculation indicate that the sulfur defects in MoS2 QDs tend to reduce the bandgap with lowering Δ\(E_{\rm ST}\), which improved ISC efficiency and account for the observed enhanced 1O2 generation in the photosensitizing process.

On the other hand, the substitution of sulfur atom with the more electronegative oxygen atom modulated the charge density distributions in MoS2 crystals, affecting the Gibbs free energy for 3O2 adsorption. To understand the binding affinity after different degrees of defect, the binding energies of 3O2 on three MoS2 QDs were calculated by DFT. As shown in Fig. 6g, the binding energies for oxygen adsorption on MoS2 QDs decrease with less sulfur defect. The binding energies of 3O2 on MoS2-2D0 are 0.15 eV, which are much larger than MoS2-1D0 (0.13 eV) and pristine MoS2 (0.09 eV). Moreover, with three sulfur atoms substituted by oxygen atoms, binding energy further increased to 0.17 eV. This result suggested that a higher defect MoS2 QD possessed a stronger binding affinity toward 3O2 adsorption, which may allow higher oxygen coverage on the surface of MoS2 QD in the energy transfer process, thus paving the way for higher ϕen in 1O2 generation.

Besides the reduced bandgap and the strengthened binding affinity between MoS2 and 3O2 (Fig. 6h), the spin-orbit perturbations (HSO) in defective MoS2 QDs could also affect the intersystem crossing in the photosensitizing process. The vibronic coupling involved in Mo–S and Mo–O bonds would be significantly increased due to the increasing degree of defects. The decrease in size increases edge sites and dangling bonds in MoS2 QDs. This further enhances the likelihood of vibrational modes hence promoting the intersystem crossing. The real exciton splitting situation due to the presence of defects and quantum confinement effect of typical semiconductor nanocrystals behavior in MoS2 QDs’ case complicated their energy state. Here the proposed singlet and triplet states of MoS2 QD structure models was under the consideration of surface molecular states of MoS2 QDs. Further investigations to understand the electronic structure and exciton of MoS2 QDs are warranted.

Defect-dependent photodynamic therapy to kill cancer cells

Inspired by defect-dependent ROS generation capacity, the photodynamic efficiency of the three MoS2 QDs for killing cancer cells were further conducted. The material biocompatibility was first investigated. Cell viability, LDH and ROS level were examined to systematically evaluate the cytotoxicity effect (biocompatibility) of three MoS2 QDs using endothelial cells as a model for a non-cancer cell type which would be in contact with introduced MoS2 QDs bioapplications. Fig. 7a suggest that no obvious toxicity of all the three MoS2 QDs on human microvascular endothelial cell (HMVEC) cells at MoS2 QDs concentration as high as 1 mM for 24 h, suggesting good biocompatibility of all three MoS2 QDs types. There was no additional upregulation of ROS as the MoS2 QDs was not irradiated with light. When increasing the dose of MoS2 QDs, there was no increasing LDH leakage due to loss of membrane integrity as a result of induced apoptosis. We next used MoS2 QDs as photosensitizers in photodynamic cancer cell therapy in an in vitro model. Using SW480 cells as model cancer cells, Calcein AM (green fluorescence) and propidium iodide (PI, red fluorescence) staining were performed to visualize live/dead cells in the cancer cell therapy process. Control cell group with light treatments only or MoS2 QDs incubation only (without light treatment) maintained high cell viability (Fig. 7b). As expected, cells incubated with higher defects MoS2-DH QDs showed considerably lower cell viability under light irradiation compared to MoS2-DM and MoS2-DL treatment groups (Fig. 7c). After being irradiated for a short 10 min, only 72% of cells incubated with MoS2-DH were viable, which further decreased to 39.7% when the irradiation time prolonged to 30 min. At the same treatment concentrations, cell viability of MoS2-DM and MoS2-DL groups decreased from 81% to 55.2 and 92% to 72% respectively, as the irradiation time was prolonged from 10 min to 30 min.

MoS2 QDs with more S defects produce more oxidative stress in cancer cells. a MoS2 QDs treatment (without light) on human endothelial cells (HMVEC) showed negligible cytotoxicity, negligible excessive ROS generation and low apoptosis induction. The measurements were performed in triplicate. b Calcein AM and PI co-staining and c cell viabilities of SW480 cells incubated with different defect laden MoS2 QDs under white light exposure. The measurements were performed in triplicate. d MoS2-DH showed the highest size reduction of 3D tumor spheroids assay. This implied high penetration of QDs into the interior of the 3D tumor spheroids mass with the highest defect group producing the highest oxidative stress that killed the cells. e Quantification of 3D tumor spheroids area post treatment and laser excitation with MoS2-DH showing the greatest cell death amongst the three MoS2 groups. Mean ± SD, n = 10, Student’s t test, p# < 0.05. Scale bar: 100 μm

These results demonstrated that MoS2 QDs with higher defects are more effective photodynamic agents to kill cancer cells over those with lower defects at the same concentration.

To further test the photodynamic efficiency in vitro on cancer cells, 3D SW480 colorectal tumor spheroids were used as a more realistic cancer model to simulate the therapeutic responses of three MoS2 QDs groups63,64. To examine the photodynamic effect, 3D tumor spheroids were incubated with different MoS2 QDs groups for 6 h to allow for increased penetration and then irradiated with white light for 30 min. After three days, as expected, the size of tumor spheroids incubated with MoS2 QDs with a single irradiation show higher degree of growth retardation compared to control group without MoS2 treatment (Fig. 7d, e, Supplementary Figure 22). More importantly, the MoS2-DH treated groups show the greatest tumor spheroids size reduction, as compared with that of the MoS2-DM and MoS2-DL groups at equivalent MoS2 concentrations. These results indicated that the degree of defects was related to the photodynamic efficiency of MoS2 QDs, showing the possible defect engineering in QDs to enhance their therapy effect while reducing their actual dosage used in clinic, thereby preventing the potential chronic side effects and complications.

Discussion

In summary, we have demonstrated the biomineralization assisted bottom-up strategy for synthesizing a wide range of QDs from the TMD family with using mild conditions. The strategy employed straightforward chemical reactions between sodium chalcogenides and transition metal chlorides or transition metal oxides with a high yield reaction within a matter of tens of seconds. Disulfide bonds were shown to be the functional group for size quality control, and further verified by DFT simulations. The major benefit of the synthetic route is the ability of controllable defects engineering on TMD QDs via tuning precursor stoichiometry. Our studies revealed that the reaction pathway of MoS2 QDs and the defective crystal structures might be \(({\mathrm{MoO}}_4)^{2 - } + {\mathrm{S}}^{2 - } \to {\mathrm{MoO}}_{{x}}{\mathrm{S}}_{2 - {{x}}}\). This synthetic strategy simplifies the synthetic process with mild conditions, enriching the TMD QDs library for exploring their physical and chemical properties and related applications. Our bottom-up strategy for synthesizing TMDs QDs provided an ideal platform for investigating the correlation between the surface defects of semiconductor nanomaterials and the corresponding capacity of anti-cancer oxidative stress generation. Strongly positive correlation between degrees of sulfur defects and photodynamic efficiencies could be observed in the prepared MoS2 QDs. The density of states and molecular dynamics calculations suggest that the sulfur defect in MoS2 QDs reduced the bandgap and strengthened the binding affinity between MoS2 QDs and 3O2. This may have contributed to the intersystem crossing and energy transfer separately in the photosensitizing process; highlighting the significant potential for defect engineering as an intrinsic alteration tool used in conjunction with existing TMDs bionanotechnologies65,66,67 without adding yet another material.

Methods

Materials

All chemicals and reagents were used as received without any further purification. MoCl5 (95%), MoO3 (95%) and Bovine Serum Album (BSA) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (USA). Deionized water was used throughout the synthesis.

Sample characterization

The morphologies and size of MoS2 QDs samples were characterized by TEM (FE-TEM; JEOL JEM-2100F, Japan). Nanoparticle sizes were determined by measuring no <200 randomly selected nanoparticles from TEM micrographs with ImageJ (http: //rsbweb.nib.gov/ij/). The powder XRD measurements were performed using a Bruker D8 advanced diffractometer with a Cu Ka irradiation in the 2θ range of 200-600. The elemental composition and binding energy of the sample were characterized by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS; AXIS HIS, Kratos Analytical). The absorbance spectrum scanning and fluorescence intensities were conducted using microplate reader (BioTEK H4FM, USA). Fluorescence imaging were taken with inverted fluorescence microscope (Leica DMI6000, Germany) and the phase contrast images were captured by inverted microscope (Olympus-CX41, Japan).

Synthesis of MoS2 quantum dots

In a typical procedure, Mo-precursor solution was firstly prepared by dissolving MoCl5 or MoO3 into dH2O by adjusting the pH value to be 11. The resultant solution was transparent and colorless after sonication. Then 1 mL of Mo precursor solution mixed into 39 mL of BSA solution (1 mg/mL) followed by adding 0.2 mL 0.5 M Na2S solution under vigorous stirring at room temperature. The pH value of the mixed solution was subsequently adjusted to 6~7 by adding 1 M HCl. After neutralizing the pH, a clear yellow solution of MoS2 quantum dots was produced quickly.

Synthesis of other TMD quantum dots with BSA

The protocol of synthesizing other TMD quantum dots was similar to MoS2 quantum dots. The only difference was the preparation of Se- and Te- precursors. In a typical preparation of Se precursor, 79.9 mg of Se powder was added into 1 mL of NaBH4 solution (80 mg) to reduce it at ambient condition. 30 min later, black Se powder disappeared completely and the clear solution was Se precursor. For the preparation of Te precursor, 31.9 mg of Te powder was added into 200 μL NaBH4 solution (28.4 mg). After 30 min, black Te powder fully disappeared and the clear solution was Te precursor. For the synthesis of WS2, RuS2, MoTe2, WSe2 and RuSe2, similarly mild conditions were carried as MoS2 above.

Photodynamic evaluation of three MoS2 QDs with ABDA

In the experiments, ABDA as the probe of 1O2 was added to different MoS2 QDs dispersion solution with final concentration of 10 μM. Then the mixture solution was transferred to a cuvette and exposed to white light (400–800 nm, 100 mW) perpendicularly for 8 min. The light source irradiated a region of 1 cm2. For the convenience of observation, the OD of three MoS2 QDs at 400 nm was adjusted to the same. The absorbance change at 400 nm was recorded at various time points to obtain the degradation rate of ABDA. For the comparison of 1O2 quantum yield, all the 1O2 quantum yield of MoS2 was normalized to that of MoS2-DL, relative 1O2 ƞ to MoS2-DL using the following equation:

where \(K_{{\rm{MoS}}_2}\) and \(K_{{\rm{MoS}_2 - D_L}}\) represent the decomposition rate constants of the photodegradation of ABDA with different MoS2, which were determined by plotting Loge(Abs0/Abs) versus irradiation, where Abs0 is the initial absorbance of ABDA, Abs is the ABDA absorbance at different irradiation time. \(A_{{\rm{MoS}}_2}\) and \(A_{{\rm{MoS}_2 - D_L}}\) refer to the light absorbed by different MoS2 and MoS2-DL respectively, which are determined by integration of the optical absorption bands in the wavelength range from 400 to 800 nm.

Intracellular ROS assay

DCF-DA probed the ROS generation inside cells. SW480 cells were cultured on 8-well cell chamber slides overnight. Overnight medium was replaced with fresh medium containing different MoS2 QDs (at 0.5 mM). After incubation for 6 h, DCF-DA (25 μM) was added for 15 min, and then either left in the dark or irradiation with white light (100 mW cm−2) for 5 min. After washing and staining the cells with Hoechst 33342 (5 μg/mL), fluorescence images of the cells were captured using Nikon A1 confocal microscope (Nikon, Japan).

Photodynamic killing of SW480 cancer cells

To assess the photodynamic effect of MoS2 QDs on SW480 cells, SW480 cells was seeded and cultured in 96-well plates overnight. Then different groups of MoS2 QDs were used to treat SW480 cells for 6 h. Subsequently, cells were irradiated with white light (100 mW cm−2) for 10 and 30 min. After treatments, the cells were further cultured for 12 h. Cell viability after different treatments was evaluated by WST assays and Tali Image based Cytometer (Life Technologies, USA).

Formation and photodynamic efficiency in SW480 colorectal tumor spheroids

To examine the photodynamic effect on 3D SW480 colorectal tumor spheroids, 3D cell spheroids were first prepared. The solidified agrose micro-molds were sterilized by UV irradiation for 30 min and then equilibrated with DMEM medium for 12 h. After that 50 μL of SW480 cell suspension were seeded into each agarose micro-mold, 5 min after the cells settle down into the micro-mold, 500 μL of DMEM medium was added to the well. After 24 h, 3D SW480 cell spheroids were formed due to gravity and the aggregation of cells. For photodynamic therapy treatment, the different MoS2 QDs were added into 3D SW480 cell spheroids. After 6 h, 3D SW480 cell spheroids were either exposed to dark or white light (100 mW cm−2) for 30 min. The images of 3D SW480 cell spheroids were captured by a light microscope (Olympus-CX41, Japan) in the subsequent days and the size of the 3D SW480 cell spheroids were measured with ImageJ software.

Density functional theory (DFT) binding energy siumlation

Adsorptions of various chemical groups on MoS2 were investigated by performing simulations at the density functional theory (DFT) level as implemented in the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP)68, with the exchange-correlation functional of Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE)69. The long-range van der Waals interactions were calculated within the Tkatchenko and Scheffler scheme to avoid the empirical parameters70, while the self-consistent screening and polarizability contraction effects were also taken into account, in view of their important roles in determining the weak inter-molecular interactions71. The MoS2 layer was modeled with a vacuum region of 20 Å. The first Brillouin zone was sampled with a k-point mesh with a plane-wave cutoff of 450 eV. The various molecules including CH3–X (X = –OH, –SH, –NH2, –COOH, –SSCH3 and –C6H5) and CH3–CONH–CH3 were simulated following the equation \(E_{{\rm{ad}}} = E_{{\rm{MoS}}_2 + {\rm{group}}} - E_{{\rm{group}}} - E_{{\rm{MoS}}_2}\) with the results summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

Methodology for density of states (DOS) of models MoS2

-

DFT based VASP.

-

PAW-PBE potential electron-ion interaction and exchange-correlation.

-

3 × 3 × 1 supercell structure is applied

-

500 eV for plane-wave expansion cutoff.

-

7 × 7 × 1 Gama-centred k-point mesh.

-

All structures were relaxed until the force is smaller than 0.001 eV/Angstrom with a total energy convergence criterion of 1 × 10−6 eV.

-

Vacuum is 15 Å.

-

The relaxed lattice parameter for MoS2 monolayer is 3.190 Å

Data availability

All the relevant data are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Chhowalla, M. et al. The chemistry of two-dimensional layered transition metal dichalcogenide nanosheets. Nat. Chem. 5, 263 (2013).

Duan, X., Wang, C., Pan, A., Yu, R. & Duan, X. Two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides as atomically thin semiconductors: opportunities and challenges. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 8859–8876 (2015).

Liu, B. et al. Synthesis and optimization of MoS2@ Fe3O4‐ICG/Pt (IV) nanoflowers for MR/IR/PA bioimaging and combined PTT/PDT/chemotherapy triggered by 808 nm laser. Adv. Sci. 4, 1600540 (2017).

Zhu, X. et al. Intracellular mechanistic understanding of 2D MoS2 nanosheets for anti-exocytosis-enhanced synergistic cancer therapy. ACS Nano 12, 2922–2938 (2018).

Yu, F. et al. Ultrasensitive pressure detection of few-layer MoS2. Adv. Mater. 29, 1603266 (2017).

Liu, K.-K. et al. Growth of large-area and highly crystalline MoS2 thin layers on insulating substrates. Nano. Lett. 12, 1538–1544 (2012).

Deng, D. et al. Catalysis with two-dimensional materials and their heterostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 218 (2016).

Liu, C. et al. Rapid water disinfection using vertically aligned MoS2 nanofilms and visible light. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 1098 (2016).

Lopez-Sanchez, O., Lembke, D., Kayci, M., Radenovic, A. & Kis, A. Ultrasensitive photodetectors based on monolayer MoS2. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 497 (2013).

Bonaccorso, F. et al. Graphene, related two-dimensional crystals, and hybrid systems for energy conversion and storage. Science 347, 1246501 (2015).

Acerce, M., Voiry, D. & Chhowalla, M. Metallic 1T phase MoS2 nanosheets as supercapacitor electrode materials. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 313 (2015).

Neville, R. & Evans, B. The band edge excitons in 2H-MoS2. Phys. Status Solidi B. 73, 597–606 (1976).

Zhang, X. et al. A facile and universal top-down method for preparation of monodisperse transition-metal dichalcogenide nanodots. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 54, 5425–5428 (2015).

Tan, C. et al. Preparation of High-Percentage 1T-phase transition metal dichalcogenide nanodots for electrochemical hydrogen evolution. Adv. Mater. 30, 1705509 (2018).

Eda, G. et al. Photoluminescence from chemically exfoliated MoS2. Nano. Lett. 11, 5111–5116 (2011).

Coleman, J. N. et al. Two-dimensional nanosheets produced by liquid exfoliation of layered materials. Science 331, 568–571 (2011).

Zhou, J. et al. A library of atomically thin metal chalcogenides. Nature 556, 355 (2018).

Yong, Y. et al. Tungsten sulfide quantum dots as multifunctional nanotheranostics for in vivo dual-modal image-guided photothermal/radiotherapy synergistic therapy. ACS Nano 9, 12451–12463 (2015).

Najafi, L. et al. Solution-processed hybrid graphene flake/2H-MoS2 quantum dot hetero-structures for efficient electrochemical hydrogen evolution. Chem. Mater. 29, 5782–5786 (2017).

Wang, Xiaojie et al. One-step synthesis of water-soluble and highly fluorescent MoS2 quantum dots for detection of hydrogen peroxide and glucose. Sens. Actuat. B-Chem. 252, 183–190 (2017).

Mishra, Himanshu et al. pH dependent optical switching and fluorescence modulation of molybdenum sulfide quantum dots. Adv. Opt. Mater. 5, 1601021 (2017).

Zhang, Shuqu et al. MoS2 quantum dot growth induced by s vacancies in a znin2s4 monolayer: atomic-level heterostructure for photocatalytic hydrogen production. ACS Nano 12, 751–758 (2017).

Samia, A. C., Chen, X. & Burda, C. Semiconductor quantum dots for photodynamic therapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 15736–15737 (2003).

Wang, Z. et al. Biomineralization-inspired synthesis of copper sulfide–ferritin nanocages as cancer theranostics. ACS Nano 10, 3453–3460 (2016).

Dong, Z. et al. Synthesis of hollow biomineralized CaCO3-polydopamine nanoparticles for multimodal imaging-guided cancer photodynamic therapy with reduced skin photosensitivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 2165–2178 (2018).

Yan, Y. et al. Facile synthesis of water-soluble WS2 quantum dots for turn-on fluorescent measurement of lipoic acid. J. Phys. Chem. C. 120, 12170–12177 (2016).

Baker, M., Gilmore, R., Lenardi, C. & Gissler, W. XPS investigation of preferential sputtering of S from MoS2 and determination of MoSx stoichiometry from Mo and S peak positions. Appl. Surf. Sci. 150, 255–262 (1999).

Chikan, V. & Kelley, D. Size-dependent spectroscopy of MoS2 nanoclusters. J. Phys. Chem. B 106, 3794–3804 (2002).

Sun, J. et al. Mechanistic understanding of excitation-correlated nonlinear optical properties in MoS2 nanosheets and nanodots: the role of exciton resonance. ACS Photonics 3, 2434–2444 (2016).

Doolen, R., Laitinen, R., Parsapour, F. & Kelley, D. Trap state dynamics in MoS2 nanoclusters. J. Phys. Chem. B 102, 3906–3911 (1998).

Narayanan, K. L. et al. Effect of irradiation-induced disorder on the optical absorption spectra of CdS thin films. Phys. B: Condens. Matter 240, 8–12 (1997).

Mocatta, David et al. Heavily doped semiconductor nanocrystal quantum dots. Science 332, 77–81 (2011).

Jean, Joel et al. Radiative efficiency limit with band tailing exceeds 30% for quantum dot solar cells. ACS Energy Lett. 2, 2616–2624 (2017).

Liu, T. et al. Drug delivery with PEgylated MoS2 nano-sheets for combined photothermal and chemotherapy of cancer. Adv. Mater. 26, 3433–3440 (2014).

Guan, G. et al. Protein induces layer-by-layer exfoliation of transition metal dichalcogenides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 6152–6155 (2015).

Guan, G. et al. Convenient purification of gold clusters by co-precipitation for improved sensing of hydrogen peroxide, mercury ions and pesticides. Chem. Commun. 50, 5703–5705 (2014).

Sun, Y. et al. Low-temperature solution synthesis of few-layer 1T’-MoTe2 nanostructures exhibiting lattice compression. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 55, 2830–2834 (2016).

Walsh, A. & Zunger, A. Instilling defect tolerance in new compounds. Nat. Mater. 16, 964 (2017).

Xie, J. et al. Controllable disorder engineering in oxygen-incorporated MoS2 ultrathin nanosheets for efficient hydrogen evolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 17881–17888 (2013).

Zhu, S. et al. Surface chemistry routes to modulate the photoluminescence of graphene quantum dots: From fluorescence mechanism to up-conversion bioimaging applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 22, 4732–4740 (2012).

Zhu, S. et al. Highly photoluminescent carbon dots for multicolor patterning, sensors, and bioimaging. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 125, 4045–4049 (2013).

Myung, Noseung, Yoonjung, Bae & Allen, J. Bard Enhancement of the photoluminescence of CdSe nanocrystals dispersed in CHCl3 by oxygen passivation of surface states. Nano. Lett. 3, 747–749 (2003).

Jang, Eunjoo et al. Surface treatment to enhance the quantum efficiency of semiconductor nanocrystals. J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 4597–4600 (2004).

Jung, Dae-Ryong et al. Semiconductor nanoparticles with surface passivation and surface plasmon. Electron. Mater. Lett. 7, 185 (2011).

Kim, I. S. et al. Influence of stoichiometry on the optical and electrical properties of chemical vapor deposition derived MoS2. ACS Nano 8, 10551–10558 (2014).

Yang, K. et al. The influence of surface chemistry and size of nanoscale graphene oxide on photothermal therapy of cancer using ultra-low laser power. Biomaterials 33, 2206–2214 (2012).

Feng, L. et al. Polyethylene glycol and polyethylenimine dual-functionalized nano-graphene oxide for photothermally enhanced gene delivery. Small 9, 1989–1997 (2013).

Venkatesan, R., Periasamy, N. & Srivastava, T. Singlet molecular oxygen quantum yield measurements of some porphyrins and metalloporphyrins. Proc. Indian Acad. Sci. Chem. Sci. 104, 713–722 (1992).

Xiao, L., Gu, L., Howell, S. B. & Sailor, M. J. Porous silicon nanoparticle photosensitizers for singlet oxygen and their phototoxicity against cancer cells. ACS Nano 5, 3651–3659 (2011).

Feng, G., Wu, W., Xu, S. & Liu, B. Far red/near-infrared AIE dots for image-guided photodynamic cancer cell ablation. ACS Appl. Mat. Interfaces 8, 21193–21200 (2016).

Matheson, I. B. C. et al. The quenching of singlet oxygen by amino acids and proteins. Photochem. Photobiol. 21, 165–171 (1975).

Cheng, L., Wang, C., Feng, L., Yang, K. & Liu, Z. Functional nanomaterials for phototherapies of cancer. Chem. Rev. 114, 10869–10939 (2014).

Peng, F. et al. Silicon nanomaterials platform for bioimaging, biosensing, and cancer therapy. Acc. Chem. Res. 47, 612–623 (2014).

Ge, J. et al. A graphene quantum dot photodynamic therapy agent with high singlet oxygen generation. Nat. Commun. 5, 4596 (2014).

Lucky, S. S., Soo, K. C. & Zhang, Y. Nanoparticles in photodynamic therapy. Chem. Rev. 115, 1990–2042 (2015).

Seidl, C. et al. Tin Tungstate nanoparticles: a photosensitizer for photodynamic tumor therapy. ACS Nano 10, 3149–3157 (2016).

Zhou, Z., Song, J., Nie, L. & Chen, X. Reactive oxygen species generating systems meeting challenges of photodynamic cancer therapy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45, 6597–6626 (2016).

Bakalova, R., Ohba, H., Zhelev, Z., Ishikawa, M. & Baba, Y. Quantum dots as photosensitizers? Nat. Biotechnol. 22, 1360 (2004).

Samia, A. C. S., Dayal, S. & Burda, C. Quantum dot-based energy transfer: perspectives and potential for applications in photodynamic therapy. Photochem. Photobiol. 82, 617–625 (2006).

Chen, Y. L. et al. Switching luminescent properties in osmium-based β-diketonate complexes. Chemphyschem 6, 2012–2017 (2005).

Xu, S. et al. Tuning the singlet-triplet energy gap: a unique approach to efficient photosensitizers with aggregation-induced emission (AIE) characteristics. Chem. Sci. 6, 5824–5830 (2015).

Zhen, X. et al. Intraparticle energy level alignment of semiconducting polymer nanoparticles to amplify chemiluminescence for ultrasensitive in vivo imaging of reactive oxygen species. ACS Nano 10, 6400–6409 (2016).

Chia, S. L., Tay, C. Y., Setyawati, M. I. & Leong, D. T. Biomimicry 3D gastrointestinal spheroid platform for the assessment of toxicity and inflammatory effects of zinc oxide nanoparticles. Small 11, 702–712 (2015).

Li, B. L. et al. Directing assembly and disassembly of 2D MoS2 nanosheets with DNA for drug delivery. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 15286–15296 (2017).

Tay, D. M. Y., Li, B. L., Tan, E. S. L., Loh, K. P. & Leong, D. T. Precise single-step electrophoretic multi-sized fractionation of liquid-exfoliated nanosheets. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1801622 (2018).

Li, B. L. et al. Emerging 0D transition-metal dichalcogenides for sensors, biomedicine, and clean energy. Small 13, 1700527 (2017).

Li, B. L. et al. Low-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenide nanostructures based sensors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 26, 7034–7056 (2016).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B. Condens. Matter 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Alexandre Tkatchenko and Matthias Scheffler.. Accurate molecular van der waals interactions from ground-state electron density and free-atom reference data. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 073005 (2009).

Gong, Wenbin, Zhang, Wei, Wang, Chengbin, Yao, Yagang & Lu, Weibang Influence of self-consistent screening and polarizability contractions on interlayer sliding behavior of hexagonal boron nitride. Phys. Rev. B 96, 174101 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the funding provided by the National Research Foundation, Prime Minister’s Office, Singapore, under Competitive Research Program (Award No. NRF- CRP13-2014-03).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.D. and D.T.L. conceived the project, the hypotheses and the experiments. X.D., F.P., W.B.G., Z.J. performed the experiments. X.D., C.T.L. and D.T.L. analyzed the results. X.D., F.P., G.S., K.P.L., C.T.L., and D.T.L. discussed the results. X.D., C.T. L. and D.T.L. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Journal Peer Review Information: Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contributions to the peer review of this work. [Peer reviewer reports are available].

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ding, X., Peng, F., Zhou, J. et al. Defect engineered bioactive transition metals dichalcogenides quantum dots. Nat Commun 10, 41 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07835-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07835-1

This article is cited by

-

MoS2 quantum dots and their diverse sensing applications

Emergent Materials (2024)

-

Chiral nanocrystals grown from MoS2 nanosheets enable photothermally modulated enantioselective release of antimicrobial drugs

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Green functional carbon dots derived from herbal medicine ameliorate blood—brain barrier permeability following traumatic brain injury

Nano Research (2022)

-

Green synthesis of Au@WSe2 hybrid nanostructures with the enhanced peroxidase-like activity for sensitive colorimetric detection of glucose

Nano Research (2022)

-

Strategies and challenges for enhancing performance of MXene-based gas sensors: a review

Rare Metals (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.