Abstract

Thermodynamic modeling has recently suggested that condensed carbonaceous matter should be the dominant product of abiotic organic synthesis during serpentinization, although it has not yet been described in natural serpentinites. Here we report evidence for three distinct types of abiotic condensed carbonaceous matter in paragenetic equilibrium with low-temperature mineralogical assemblages hosted by magma-impregnated, mantle-derived, serpentinites of the Ligurian Tethyan ophiolite. The first type coats hydroandraditic garnets in bastitized pyroxenes and bears mainly aliphatic chains. The second type forms small aggregates (~2 µm) associated with the alteration rims of spinel and plagioclase. The third type appears as large aggregates (~100–200 µm), bearing aromatic carbon and short aliphatic chains associated with saponite and hematite assemblage after plagioclase. These assemblages result from successive alteration at decreasing temperature and increasing oxygen fugacity. They affect a hybrid mafic-ultramafic paragenesis commonly occurring in the lower oceanic crust, pointing to ubiquity of the highlighted process during serpentinization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

At slow and ultraslow Mid-Ocean Ridges (MORs), mantle-derived rocks are progressively serpentinized by aqueous fluids that circulate through the upper lithosphere. By producing H2-bearing fluids, these environments are considered to be favorable for the chemical reduction of magmatic inorganic carbon species (CO/CO2) or seawater carbonate ions1,2. Up to now, abiotic methane (CH4), short-chain hydrocarbons and carboxylic acids were accordingly identified in hydrothermal fluids discharged at MORs3,4,5,6,7 or in products from analog experiments1,8,9. However, experimental studies and thermodynamic calculations have recently shown that carbonaceous phases should be dominantly produced during serpentinization10,11. Yet natural occurrences of Condensed Carbonaceous Matter (CCM) were rarely reported. Graphitic material has been described in association with ultramafic rocks from different ophiolites, e.g., refs. 12,13 while poorly-structured CCM aggregates, sometimes considered as biologic in origin, have been identified in serpentinites from the Mid-Atlantic Ridge14,15,16 and in serpentinized gabbroic and peridotitic xenoliths17,18,19.

The samples here described were collected in the Northern Apennine ophiolites, which are lithospheric remnants of the Piedmont-Ligurian oceanic basin, a branch of the Mesozoic Tethys20 (Fig. 1). The oceanic sequence is formed by mantle peridotites, once exposed at the seafloor, intruded by sparse gabbroic bodies and a discontinuous basaltic cover. This association presents strong similarities with present-day non-volcanic passive margins and ultra-slow spreading ridge settings20,21. Our study focuses on a small serpentinitic body (150 m-long; Fig. 1b) pertaining to the Val Baganza unit of the External Ligurides22. Mineral paragenesis and nature of the organic matter disseminated in these serpentinites confirm previous studies showing that this unit was not affected by metamorphic overprint during orogenetic exhumation and obduction23.

Results

A multistage aqueous alteration history

The protolith of the studied serpentinite is a mantle-harzburgite, equilibrated in the spinel-stability field, impregnated at high temperature (~1200 °C) by a percolating melt as attested by the presence of secondary magmatic spinel and plagioclase ghosts (Supplementary Fig. 1). The progressive retrograde hydration trend of the protolith is recorded by a sequence of temperature-decreasing parageneses. The pervasive high-temperature serpentinization assemblage (T > 300 °C)24 is characterized by mesh textured lizardite + magnetite and bastite (i.e., fine-grained lizardite), substituting primary olivine and orthopyroxene, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Tables 1, 2). These textural and mineralogical relationships closely match those formed during present-day serpentinization of abyssal mantle peridotites24.

The serpentine groundmass presents discrete microtextural domains hosting different parageneses. Residual and magmatic spinels developed inward ferritchromite (Ftc) rims (Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Tables 3, 4). The ferritchromite is itself composed of a submicrometric association of Cr-magnetite (Cr-Mag), chlorite and lizardite; it displays low Fe3+# (100 × Fe3+/(Fe3+ + Cr + Al); mean = 25.87 ± 12.76; Supplementary Table 4), suggesting low temperatures of alteration ( ≤ 200 °C)25. Ferritchromite is commonly surrounded by outward chlorite rims (Chl1), resulting from the interaction between the surrounding serpentine and the cations (Mg2+, Al3+) released during the spinel alteration26 (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. 1, and Supplementary Tables 5, 6).

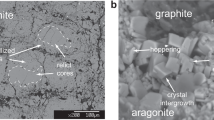

Association of large patches of Condensed Carbonaceous Matter (CCM) with hematite (Hem) and saponite (Sap) assemblage (HemSap) shown by backscattered electron SEM images . a The HemSap assemblage grew at the expense of chlorite (Chl2) ± serpentine (Srp) ± type 2-hydroandradite (Hadr-2) resulting from plagioclase pseudomorphosis. The former plagioclase surrounded primary spinel (Spl) now displaying limited ferritchromite (Ftc) rims. b Same assemblage grew over the pseudomorphs of former interstitial plagioclase. c Large patches of CCM coating hematite and invading microcracks affecting saponite. d Associated elemental distributions of carbon (red), iron (green) and magnesium (blue). Scale bars correspond to 200 µm

After the development of the ferritchromite rims we observe four low-temperature micro-parageneses. The first, named BastHadr, is composed of elongated and chemically-zoned hydroandraditic garnets (Hadr-1; Fig. 3) hosted in bastitic serpentine replacing orthopyroxene. The hydroandradites are rich in Ti and Cr (Supplementary Table 7) and grew following the clinopyroxene exsolution lamellae within orthopyroxene. They display narrow and elongated cavities filled with lizardite (Fig. 3c). The second paragenesis is composed of cryptocrystalline clinochlore ± lizardite ± hydroandradite pseudomorphs on plagioclase (Chl2 ± Srp ± Hadr-2; Fig. 2, Supplementary Tables 8, 9). Unlike Hadr-1, these hydroandradites (Hadr-2) are made of nanocrystal selvages, poor in Cr and Ti (Supplementary Table 9). The third assemblage, made of Fe-rich Mg-saponite and hematite (HemSap; Fig. 2) is located only within the plagioclase ghosts, suggesting that it derives directly from plagioclase relicts or from the Chl2 ± Srp ± Hadr-2 assemblage. Although a replacement of plagioclase relicts cannot be completely excluded, the HemSap domains and the Chl2 ± Srp ± Hadr-2 domains clearly intertwine (Fig. 2b, c), with a decrease of the chlorite and hydroandradite proportions toward the domain borders, in favor of a progressive inward alteration of the Chl2 ± Srp ± Hadr-2 domain to saponite. Local interlayering of chlorite within saponite supports local replacement of Chl2 ± Srp ± Hadr-2 pseudomorphs after plagioclase (Supplementary Tables 10, 11). Saponite displays high content in Fe (up to ~7%Wt; Supplementary Table 10). In the same domains, hematite (Supplementary Table 12) forms rosettes interlocked with serpentine, saponite and chlorite. Hematite is always found in association with saponite but the reverse is not true, suggesting that hematite grew at the expense of saponite. Variably altered spinels are commonly preserved within the pseudomorphs (Fig. 2). The fourth low-temperature paragenesis contains large hydroandradites (Hadr-3; Fig. 2a and Supplementary Table 13) developed on the edges of serpentine veins (Supplementary Table 14), growing along serpentine fibers. Their Cr2O3 and TiO2 contents are similar to Hadr-2 and Hadr-1, respectively (Supplementary Table 13).

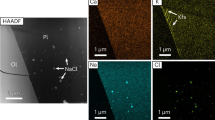

Association of CCM with type 1-hydroandradite (Hadr-1) and bastite assemblage (BastHadr). a Backscattered electron SEM image showing a thin organic film coating the surface of Hadr-1 growing subparallel to the exsolution planes of the primary pyroxene. b Associated elemental distributions of carbon (red), iron (green) and magnesium (blue). c Backscattered electron SEM image showing that CCM is also present in the cavities of Hadr-1. Scale bars correspond to 20 µm

Multiple occurrences of condensed carbonaceous matter

Significant amounts of CCM have been identified by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and characterized by Raman and Fourier transform-infrared (FTIR) spectroscopies. CCM occurrences are associated with three out of the four low-temperature micro-parageneses described above, namely the bastite-hosted hydroandradite Hadr-1 (CCM-BastHadr), the pseudomorphosed plagioclase (Chl2 ± Srp ± Hadr-2) coupled to the ferritchromite rims (CCM-PPFtc), and the hematite + Fe-rich Mg-saponite assemblage (CCM-HemSap) (Figs. 2–5). CCM aggregates display differences in size and composition among the various mineralogical assemblages. The rare and very small (~2 µm) CCM-PPFtc occurrences (Fig. 4) were not analyzed by Raman and FTIR spectroscopy due to intense fluorescence and their too small size, respectively.

Association of CCM with ferritchromite (Ftc) rims contouring altered primary spinel and pseudomorphosed plagioclase substituted by Chl2 ± Srp ± Hadr-2 (PPFtc assemblage). Backscattered electron SEM images showing the presence of rare and small patches of condensed carbonaceous material (CCM-PPFtc), highlighted by white arrows. Scale bar corresponds to 50 µm

Raman spectra for CCM-BastHadr and CCM-HemSap assemblages and assignment of the different bands. 1: Hydroandradite, 2: Cr3+ luminescence, 3: CH2 wagging, 4: CH deformation, 5: CH3 in aliphatic compounds (CH3 symmetric deformation), 6: CH2 and CH3 in aliphatic chains (bending, scissoring, antisymmetric stretching), 7: Aliphatic COOH, 8: COO− antisymmetric stretching, 9: C-C aromatic or phenyl, 10: COO− symmetric stretching, 11: C=C aromatic, 12: C-C aromatic ring stretching. Assignment was done using refs. 28, 29. For the exact position of the bands see Supplementary Table 15

The CCM-BastHadr appears as thin films ( < 6 μm) coating Hadr-1 crystals and their inner cavities (Fig. 3). The associated Raman spectrum (Fig. 5, Supplementary Table 15) shows two large bands in the 1100-1450 cm-1 region, corresponding to Cr3+ luminescence in garnet27. Although these bands partially mask the organic signal, CH2 and CH3 vibration bands can still be recognized on their shoulders. Intense bands corresponding to aliphatic COOH (1532 cm−1)28 can be observed in the 1400-1800 cm-1 region. Another band corresponding to COO− stretching can be detected but no clear C=C vibrations characteristic of aromatic moieties were identified29. The CCM-HemSap assemblages form large aggregates up to 100–150 µm in size. They are mainly associated with hematite, filling the mineral embayments and cracks developed during the retrograde transformation of Chl2 ± Srp ± Hadr-2 into Fe-rich Mg-saponite (Fig. 2). The associated Raman spectrum displays CH3 and CH2 vibrations suggesting the presence of aliphatic chains, as confirmed by FTIR spectroscopy (Supplementary Fig. 2). The mean methylene to methyl ratio RCH2/CH3 (1.47 ± 0.45; Supplementary Table 16) indicates short aliphatic chains, bearing up to 6–8 carbon atoms30. Contrarily to CCM-BastHadr, CCM-HemSap assemblages display several vibration bands characteristic of aromatic moieties (Fig. 5, Supplementary Table 15).

Discussion

The strict spatial association between the organic and mineralogical phases suggests that the different forms of CCM are in paragenetic equilibrium with secondary mineral phases. This observation, supported by the systematic association of a given CCM type with a given mineral paragenesis, indicates that CCM formation could have occurred simultaneously to the growth of the host mineralogical assemblage, thus suggesting an abiotic endogenic genesis. Additionally, the CCM spectral signatures reported here (Fig. 5) lack evidence of protein-forming amide groups of biological origin, such as those previously reported in oceanic serpentinites14,15. A CCM genesis after thermal degradation of pristine biogenic material can also be excluded based on Raman spectra that do not display the expected broad bands of graphitic carbon (~1340–1360 and 1580–1610 cm−1)31 that would be produced by this process.

Casale samples show that the amount of CCM varies among the observed mineral assemblages: minor in the plagioclase pseudomorphs coupled to the ferritchromite rims (CCM-PPFtc), more important in the BastHadr domains (CCM-BastHadr) and massive in the HemSap paragenesis (CCM-HemSap). The last two CCM pools while presenting a similar aliphatic character, differ in their carboxylic pattern: the CCM-BastHadr assemblage shows a higher content in carboxylic functional groups whereas aromatic carbon is present in the CCM-HemSap assemblage. While the hydration of olivine was considered as the only putative reaction pathway for CCM formation in recent thermodynamic calculations11, these observations are suggestive of differential formation pathways and productivity possibly implying differences in the synthesis mechanism and limiting factors at local scale.

The formation of non-graphitic CCM in serpentinization-related systems was thermodynamically predicted to occur during olivine serpentinization in the 200–400 °C temperature interval11. At these temperatures CCM forms preferentially provided that CH4 is kinetically inhibited2,8,9,32,33,34. Our data confirm and significantly extend CCM abiotic synthesis to diverse mafic and ultramafic mineral precursors and lower temperature ranges. Overall, the low-temperature parageneses found in the Casale serpentinite are progressive steps of a low-temperature alteration sequence resulting from increasing oxidizing conditions occurring during the uplifting of the oceanic mantle and its exposition to the seafloor. The crystallization and stability fields of these low-temperature assemblages give constraints on the formation of CCM-BastHadr and CCM-PPFtc assemblages during hydrothermal alteration at depth in an oceanic subaxial environment (< 10 km). The crystallization of hydroandradite occurs at temperatures < 200 °C, low oxygen fugacity, low CO2 partial pressure and low silica activity35. The CCM-HemSap assemblage was formed later at lower temperatures, higher silica activity and in a slightly-more oxidized environment, as suggested by the presence of Fe-rich Mg-saponite and hematite35,36. Saponite, a common secondary or tertiary product of hydrothermal alteration of mafic and ultramafic minerals35,36,37,38,39 can form under a wide range of temperatures, from 20 to 300 °C40,41. The saponite enrichment in Fe and its mixed valence can be related to slow alteration at low temperature (<150 °C) in the upper most portion of the crust during uplifting and progressive exposure at the seafloor of mantle-derived rocks to cold and oxidizing seawater-derived fluids at increasing water/rock ratio as the reaction progresses41,42,43,44. Similar or close conditions are likely kept during the crystallization of hematite linked to the destabilization of Fe-rich Mg-saponite by oxidizing fluids36. When saponite is oxidized, nontronite is generally the main by-product at high water/rock ratios (ca. 1000)36. On the contrary, at low water/rock ratios (ca. 1), hematite becomes an additional by-product of saponite oxidation. It can be the sole product if the O2 dissolved in the fluids is as low as 0.008–0.010 g O2 per gram of rock36.

In low-temperature serpentinizing environments, the reduction of inorganic carbon to organic compounds is partly driven by the availability of H2. Its generation results from water reduction associated with oxidation of Fe2+-bearing minerals (olivine, pyroxene and serpentine)45,46. Above 300 °C, this reaction is fast and efficient, and a large quantity of H2 is produced while the resulting Fe3+ is stored mainly in magnetite45,46,47. Below 200 °C, the production of H2 and hence the abiotic synthesis potential should decrease because of slower reaction kinetics and partitioning of Fe2+ into secondary minerals45,46,47,48. Nonetheless, the low-temperature formation of ferric-serpentine and hydroandradite as serpentinization reaction by-products has been suggested as an efficient process for H2 production49,50. Similarly, the formation of ferritchromite rims where spinel Fe2+ is oxidized in Fe3+-bearing Cr-magnetite and the later crystallization of hematite are also potential sources for H248,50.

Dihydrogen availability released by mineral reactions is likely not the only factor impacting local CCM productivity. Below 200 °C, the presence of a catalyst is required to initiate carbon reduction reactions32. For instance, provided that the fluid contained comparable inorganic carbon content, CCM is not systematically found in association with hydroandradite even though its formation produces 1 mole of H2 per mole of hydroandradite crystallized50. Significantly, CCM appears associated with the hydrogarnets of the BastHadr associations (Hadr-1) that show Cr-rich rims containing up to 2.7%Wt of Cr2O3 (Supplementary Table 7). Cr3+ is an efficient catalyst33 and may have played a catalytic role at the surface of Hadr-1, promoting the peripheral formation of the CCM-BastHadr assemblage. Conversely, the CCM-PPFtc occurrences are limited to thin films on the spinel borders and tiny nuggets dispersed in the surrounding Chl2 ± Srp ± Hadr-2 pseudomorphs on plagioclase (Fig. 4). Hadr-2 has in fact low amount of Cr3+ (mean Cr2O3~0.4%Wt; Supplementary Table 9), thus a likely low catalytic capability. Moreover, while spinels are thought to promote organic synthesis33,51,52, the growth of Fe3+-hydroxides at their surface during alteration can limit internal Fe2+ oxidation and associated H2 delivery48. This is supported by the low measured Fe3+# of the spinel Ftc rims (Supplementary Table 4). The surrounding paragenesis is composed of Fe2+-bearing phases (Chl1, Chl2, Srp, ferritchromite i.e., Chl, Srp, Cr-Mag; Supplementary Tables 4, 5, 6, 8) suggesting an overall limited oxidation of the primary phase and hence limited H2 production. This mineral aggregation at the ferritchromite surface may also have acted as barrier for Fe2+ diffusion from external sources that would have sustained a longer generation of H248 and thus higher CCM production.

The most abundant CCM accumulations are found in the HemSap domains. We propose they originate from the interplay between the capability of hematite to produce H2 during its formation48,50 and the cation exchange capacity of the saponite structure53. Octahedral Fe2+ and Fe3+ for Mg2+ and tetrahedral Al3+ and Fe3+ for Si4+ heterovalent substitutions in the Fe-rich Mg-saponite silicate layers (Supplementary Tables 10, 11) may create charge unbalances in the octahedral and tetrahedral sheets53. Moreover, saponite appears to be highly heterogeneous at the micrometric scale with varying quantities of Fe3+ and Fe2+ in various coordination numbers (Supplementary Tables 10, 11). The charge unbalance promotes the exchange of cations in the clay mineral interlayers53. It also provides catalytic acid sites in the tetrahedral layers that may promote direct adsorption/intercalation, retention, and polymerization of organic compounds53. Chemical formulas calculated for the Fe-rich Mg-saponite also reveal a high octahedral occupancy that nicely agrees with the possible presence of transition metals (Cr, Ni, Fe, Mn, and Mg; Supplementary Tables 10, 11) in the saponite interlayers. These cations would further promote the complexation of organic compounds53. Coupled to the H2 produced during the crystallization of hematite, this would promote further CCM formation.

Microscopy and microspectroscopy techniques allowed for the first time to document the occurrence of different types of abiotic condensed carbonaceous matter within natural serpentinites. These occurrences are strictly associated with particular low-temperature mineralogical assemblages, suggesting that the organic material is in paragenetic equilibrium with each mineral assemblage. As compiled in Fig. 6, the formation of the different assemblages occurs at decreasing temperatures and (slightly) increasing dissolved O2 concentrations, showing that CCM formation does not occur in a single event during aqueous alteration of the oceanic lithosphere. The slight change in oxygen concentrations necessary to produce Fe3+-oxides36 is likely not sufficient to prevent the continuous formation of CCM given that the saponite and hematite surfaces provide locally reducing micro-domains48. The combination of enhanced H2 production due to hematite crystallization coupled to the saponite/hematite catalytic capabilities is a possible highly efficient engine to produce large CCM accumulations. Such process could be widespread in mafic/ultramafic-hosted hydrothermal systems at MORs, thus storing effectively organic carbon below the oceanic seafloor in a relatively immobile form. The condensed carbonaceous material can be preserved on the long term like in the Casale samples here described, or serve as carbon sources for deep microbial ecosystems14, with also the potential to impact abiotic synthesis pathways including dihydrogen or methane generation11.

Conceptual model of the different events that lead to the generation of condensed carbonaceous matter (CCM) associated with mineralogical transitions during the low-temperature aqueous alteration of the Casale serpentinite. a Primary paragenesis. Mantle harzburgite equilibrated in the spinel-stability field. b Magmatic intrusion. Impregnation of the protolith at high temperature (T ~ 1200 °C) by percolating melts, resulting in the growth of secondary spinels and plagioclases. c–e Aqueous alteration at decreasing temperatures. c Serpentinization at high temperature (T > 300 °C) of the protolith, giving rise to bastite and mesh textured lizardite and magnetite, followed by low-temperature alteration (T~200 °C) of the serpentinized assemblage at low O2 fugacity and low silica activity. These low-T aqueous alteration phases gave rise to (1) the growth of ferritchromite rims on spinels and the pseudomorphosis of plagioclase into cryptocrystalline clinochlore ± lizardite ± hydroandradite (Chl2 ± Srp ± Hadr-2) assemblage, (2) the growth of hydroandradite (Hadr-1) in the bastitized orthopyroxene, and (3) the growth of hydroandradite (Hadr-3) in late serpentine veins. These different parageneses served as catalyst for the formation of different types of CCM, specifically associated with Hadr-1 (CCM-BastHadr assemblage, bearing mainly aliphatic chains) and with plagioclase pseudomorphs and ferritchromite rims (CCM-PPFtc assemblage). d Alteration of the low-T assemblages by colder ( < 150 °C) fluids with increased silica activity and slowly-increasing O2 fugacity. It resulted in the replacement of the Chl2 ± Srp ± Hadr-2 assemblage by saponite. e Crystallization of hematite at the expense of saponite at slightly-increased O2 fugacity and low water/rock ratio. The catalytic properties of saponite and hematite gave rise to large aggregates of CCM (CCM-HemSap assemblage) formed in paragenetic equilibrium and bearing aromatic carbon and short aliphatic chains

Methods

Sample preparation

To limit any laboratory contamination, samples were carefully prepared in a clean organic-free environment. Inner cores of the collected samples were extracted with a saw treated with 5% sodium hypochlorite. Cutting has been done with sterilized demineralized water. From these cores, thin sections and manually-prepared double-polished resin-free and glue-free chips were prepared using silicon carbide polishing disks.

Scanning electron microscopy

SEM images were collected at the Centro Interdipartimentale Grandi Strumenti (CIGS, Università di Modena e Reggio Emilia, Italy) on uncoated thin sections in backscattered and secondary electron modes under low vacuum using an environmental scanning electron microscope Quanta-200 (Fei Company–Oxford Instruments). Analytical conditions were 12–20 kV accelerating voltage, low current and a 10.8–11.8 mm working distance. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy analyses were carried out with an Oxford INCA-350 spectrometer. Elemental distributions and images were processed using the INCATM software.

Raman spectroscopy

Raman spectra were collected on thin sections and free-standing samples (i.e., without any glue or resin) using two Jobin Yvon LabRAM™ microspectrometers (CIGS, Modena and Department of Physic and Earth Sciences of the University of Parma, Parma, Italy) using the 632.81 nm wavelength of a 20 mW He-Ne laser focused through a Olympus BX40 microscope with × 100 objective (Numerical Aperture (NA) = 0.9). Laser excitation was adjusted to an on-sample intensity inferior to 2 mW with integration time of 3 × 100 s, well below the critical dose of radiation that can damage carbonaceous material. This configuration yielded a planar resolution close to 1 μm. Acquisitions were obtained with a 1800 l/mm grating illuminating a Pelletier-cooled 1024 × 256 pixel CCD array detector. Punctual analyses were carried out in static mode with a spectral detection range of 200–2000 cm−1. Beam centering and Raman spectra calibration were performed daily on a quartz crystal with a characteristic SiO2 Raman band at 463.5 cm−1. To exclude any organic contamination, carbonaceous matter spectra collected on conventional thin sections were systematically compared to the ones obtained on resin- and glue-free samples. Data were processed with LabRAM™ and WiRE 3.3™ softwares.

Fourier transform-infrared microspectroscopy

FTIR measurements were performed on a Thermo Scientific Nicolet iN10 MX imaging microscope (IPGP, Paris, France). Data were acquired with a conventional Ever-Glo™ infrared source equipped with a × 15 objective (NA = 0.7) and a liquid nitrogen cooled MCT-A detector. Spectra were collected as punctual analysis or in mapping mode. In punctual analysis mode, spectra were recorded in reflection with an incident beam collimated to a sample area of 20 × 20 µm², a spectral range of 600-4000 cm−1 and a spectral resolution of 4 cm−1. Each punctual analysis corresponded to the sum of 512 accumulations converted to absorbance with Omnic™ Picta™ software (Thermo Scientific). To increase the statistic value of the methylene to methyl ratio (RCH2/CH3) obtained for CCM-HemSap assemblages, maps were collected in transmission on organic-rich zones. With this aim, the incident beam was collimated to a 20 × 20 µm² sample area, the spectral acquisition range was 600–4000 cm−1, the spectral resolution was 8 cm−1 and 64 spectra were accumulated for each pixel. Absorption bands in the spectral region of aliphatic moieties stretching (2800–3000 cm−1) were fitted using a Gaussian-Lorentzian function with the WiRE 3.3™ software. RCH2/CH3 was calculated following ref. 26 based on the intensities of the fitted asymmetric stretching bands of CH2 (~2930 cm-1; ICH2) and CH3 (~2960 cm-1; ICH3) (RCH2/CH3 = ICH2/ICH3; Supplementary Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 16).

Electron microprobe analysis

Mineral chemistry was characterized by electron microprobe analysis (EMPA) with the Cameca SXFive installed at CAMPARIS, University Pierre et Marie Curie (Paris, France). Thin sections were coated with carbon once all the other analyses were achieved. Operating conditions were 15 kV and ~10 nA. Analyses were acquired in punctual mode and in stage map mode (grid pattern). Maps (300 × 250 pixels) were generated with a 1 µm step and a 0.1 s dwell time. For each pixel characteristic of a mineral, the percentage in weight (%Wt) of each element analyzed and mineral formula were retrieved (Supplementary Tables 1-5, 7-10, 12-14).

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information File.

References

McCollom, T. M. & Seewald, J. S. Experimental constraints on the hydrothermal reactivity of organic acids and acid anions: I. Formic acid and formate. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 67, 3625–3644 (2003).

McCollom, T. M. & Seewald, J. S. A reassessment of the potential for reduction of dissolved CO2 to hydrocarbons during serpentinization of olivine. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 65, 3769–3778 (2001).

Proskurowski, G. et al. Abiogenic hydrocarbon production at Lost City hydrothermal field. Science 319, 604–607 (2008).

Konn, C. et al. Hydrocarbons and oxidized organic compounds in hydrothermal fluids from Rainbow and Lost City ultramafic-hosted vents. Chem. Geol. 258, 299–314 (2009).

Lang, S. Q., Butterfield, D. A., Schulte, M., Kelley, D. S. & Lilley, M. D. Elevated concentrations of formate, acetate and dissolved organic carbon found at the Lost City hydrothermal field. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 74, 941–952 (2010).

Holm, N. G. & Charlou, J. L. Initial indications of abiotic formation of hydrocarbons in the Rainbow ultramafic hydrothermal system, Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 191, 1–8 (2001).

Charlou, J. L., Donval, J. P., Fouquet, Y., Jean-Baptiste, P. & Holm, N. G. Geochemistry of high H2 and CH4 vent fluids issuing from ultramafic rocks at the Rainbow hydrothermal field (36°14′N, MAR). Chem. Geol. 191, 345–359 (2002).

McCollom, T. M. Carbon in Earth Ch15. In: R. Hazen, A. Jones, J. Baross eds.) Reviews in Mineralogy 75, (467–494. Mineralogical Society of America, Chantilly, 2013).

Seewald, J. S., Zolotov, M. Y. & McCollom, T. Experimental investigation of single carbon compounds under hydrothermal conditions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 70, 446–460 (2006).

McCollom, T. M. et al. Temperature trends for reaction rates, hydrogen generation, and partitioning of iron during experimental serpentinization of olivine. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 181, 175–200 (2016).

Milesi, V., McCollom, T. M. & Guyot, F. Thermodynamic constraints on the formation of condensed carbon from serpentinization fluids. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 189, 391–403 (2016).

Luque, F. J., Pasteris, J. D., Wopenka, B., Rodas, M. & Barrenechea, J. F. Natural fluid deposited graphite: Mineralogical characteristics and mechanisms of formation. Am. J. Sci. 298, 471–498 (1998).

Miura, M., Arai, S. & Mizukami, T. Raman spectroscopy of hydrous inclusions in olivine and orthopyroxene in ophiolitic harzburgite: Implications for elementary processes in serpentinization. J. Mineral. Petrol. Sci. 106, 91–96 (2011).

Ménez, B., Pasini, V. & Brunelli, D. Life in the hydrated suboceanic mantle. Nat. Geosci. 5, 133–137 (2012).

Pasini, V. et al. Low temperature hydrothermal oil and associated biological precursors in serpentinites from mid-ocean ridge. Lithos 178, 84–95 (2013).

Pikovskii, Y. I., Chernova, T. G., Alekseeva, T. A. & Verkhovskaya, Z. I. Composition and nature of hydrocarbons in modern serpentinization areas in the ocean. Geochem. Int. 42, 971–976 (2004).

Ciliberto, E. et al. Aliphatic hydrocarbons in metasomatized gabbroic xenoliths from Hyblean diatremes (Sicily): Genesis in a serpentinite hydrothermal system. Chem. Geol. 258, 258–268 (2009).

Scirè, S. et al. Asphaltene-bearing mantle xenoliths from Hyblean diatremes, Sicily. Lithos 125, 956–968 (2011).

Manuella, F. C., Carbone, S. & Barreca, G. Origin of saponite-rich clays in a fossil serpentinite-hosted hydrothermal system in the crustal basement of the Hyblean Plateau (Sicily, Italy). Clays Clay Miner. 60, 18–31 (2012).

Marroni, M. & Pandolfi, L. The architecture of an incipient oceanic basin: A tentative reconstruction of the Jurassic Liguria-Piemonte basin along the Northern Apennines-Alpine Corsica transect. Int. J. Earth Sci. 96, 1059–1078 (2007).

Manatschal, G. & Müntener, O. A type sequence across an ancient magma-poor ocean-continent transition: the example of the western Alpine Tethys ophiolites. Tectonophysics 473, 4–19 (2009).

Plesi, G. et al. Note illustrative della Carta Geologica d’Italia alla scala 1: 50.000, Foglio 235 “Pievepelago”. Serv. Geol. d’Italia-Regione Emilia Romagna, Roma Pliny Elder (77–78 AD). Hist. mundi Nat. II(2002).

Marroni, M., Molli, G., Ottria, G. & Pandolfi, L. Tectono-sedimentary evolution of the external liguride units (Northern Appennines, Italy): Insights in the pre-collisional history of a fossil ocean-continent transition zone. Geodin. Acta 14, 307–320 (2001).

Mével, C. Serpentinization of abyssal peridotites at mid-ocean ridges. C. R. Geosci. 335, 825–852 (2003).

Saumur, B. M. & Hattori, K. Zoned Cr-spinel and ferritchromite alteration in forearc mantle serpentinites of the Rio San Juan Complex, Dominican Republic. Mineral. Mag. 77, 117–136 (2013).

Mellini, M., Rumori, C. & Viti, C. Hydrothermally reset magmatic spinels in retrograde serpentinites: Formation of ‘ferritchromit’ rims and chlorite aureoles. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 149, 266–275 (2005).

Gaft, M, Reisfeld, R. & Panczer, G Modern Luminescence Spectroscopy of Minerals and Materials. Ch 4. (Springer, New York, 2015).

Marshall, C. P., Carter, E. A., Leuko, S. & Javaux, E. J. Vibrational spectroscopy of extant and fossil microbes: Relevance for the astrobiological exploration of Mars. Vib. Spectrosc. 41, 182–189 (2006).

Maquelin, K. et al. Identification of medically relevant microorganisms by vibrational spectroscopy. J. Microbiol. Methods 51, 255–271 (2002).

Lin, R. & Ritz, G. P. Studying individual macerals using I.R. microspectrometry, and implications on oil versus gas/condensate proneness and ‘low-rank’ generation. Org. Geochem. 20, 695–706 (1993).

Sforna, M. C., van Zuilen, M. A. & Philippot, P. Structural characterization by Raman hyperspectral mapping of organic carbon in the 3.46 billion-year-old Apex chert, Western Australia. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 124, 18–33 (2014).

McCollom, T. & Seewald, J. Abiotic synthesis of organic compounds in deep-sea hydrothermal environments. Chem. Rev. 107, 382–401 (2007).

Foustoukos, D. I. & Seyfried, W. E. Jr. Hydrocarbons in hydrothermal vent fluids: The role of chromium-bearing catalysts. Science 304, 1002–1005 (2004).

Berndt, M. E., Allen, D. E. & Seyfried, W. E. Reduction of CO2 during serpentinization of olivine at 300°C and 500 bar. Geology 24, 351–354 (1996).

Frost, R. B. & Beard, J. S. On silica activity and serpentinization. J. Petrol. 48, 1351–1368 (2007).

Catalano, J. G. Thermodynamic and mass balance constraints on iron-bearing phyllosilicate formation and alteration pathways on early Mars. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 118, 2124–2136 (2013).

Yang, H.-Y. & Shau, Y.-H. The altered ultramafic nodules from Mafu and Liutsu, Hsinchuhsien, northern Taiwan with particular reference to the replacement of olivine and bronzite by saponite. Spec. Publ. Cent. Geol. Surv. 5, 39–58 (1991).

Hicks, L. J., Bridges, J. C. & Gurman, S. J. Ferric saponite and serpentine in the nakhlite martian meteorites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 136, 194–210 (2014).

Alt, J. C. et al. Subsurface structure of a submarine hydrothermal system in ocean crust formed at the East Pacific Rise, ODP/IODP Site 1256. Geochem., Geophys 11, Q10010 (2010).

Percival, J. P. & Ames, D. E. Clay mineralogy of active hydrothermal chimneys and associated mounds, Middle Valley, northern Juan de Fuca Ridge. Can. Mineral. 31, 957–971 (1993).

Aoki, S., Kohyama, N. & Hotta, H. Hydrothermal clay minerals found in sediment containing yellowish-brown material from the Japan Basin. Mar. Geol. 129, 331–336 (1996).

Bach, W., Garrido, C. J., Paulick, H., Harvey, J. & Rosner, M. Seawater-peridotite interactions: First insights from ODP Leg 209, MAR 15°N. Geochem. Geophys 5, Q09F26 (2004).

Alt, C., Honnorez, J., Laverne, C. & Emmermann, R. Hydrothermal alteration of a 1 km section through the upper oceanic crust, deep sea drilling project hole 504B: mineralogy, chemistry, and evolution of seawater-basalt interactions. J. Geophys. Res. 91, 10309–10335 (1986).

Alt, J. C. et al. The role of serpentinites in cycling of carbon and sulfur: Seafloor serpentinization and subduction metamorphism. Lithos 178, 40–54 (2013).

McCollom, T. M. & Bach, W. Thermodynamic constraints on hydrogen generation during serpentinization of ultramafic rocks. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 73, 856–875 (2009).

Marcaillou, C., Muñoz, M., Vidal, O., Parra, T. & Harfouche, M. Mineralogical evidence for H2 degassing during serpentinization at 300°C/300 bar. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 303, 281–290 (2011).

Klein, F. et al. Iron partitioning and hydrogen generation during serpentinization of abyssal peridotites from 15°N on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 73, 6868–6893 (2009).

Mayhew, L. E., Ellison, E. T., McCollom, T. M., Trainor, T. P. & Templeton, A. S. Hydrogen generation from low-temperature water-rock reactions. Nat. Geosci. 6, 478–484 (2013).

Klein, F. et al. Magnetite in seafloor serpentinite-Some like it hot. Geology 42, 135–138 (2014).

Plümper, O., Beinlich, A., Bach, W., Janots, E. & Austrheim, H. Garnets within geode-like serpentinite veins: Implications for element transport, hydrogen production and life-supporting environment formation. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 141, 454–471 (2014).

Stevens, T. O. & McKinley, J. P. Abiotic controls on H2 production from basalt-water reactions and implications for aquifer biogeochemistry. Environ. Sci. Technol. 34, 826–831 (2000).

Fu, Q., Sherwood Lollar, B., Horita, J., Lacrampe-Couloume, G. & Seyfried, W. E. Abiotic formation of hydrocarbons under hydrothermal conditions: Constraints from chemical and isotope data. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 71, 1982–1998 (2007).

Meunier, A., Petit, S., Cockell, C. S., El Albani, A. & Beaufort, D. The Fe-rich clay microsystems in basalt-komatiite lavas: Importance of Fe-smectites for pre-biotic molecule catalysis during the Hadean eon. Orig. Life Evol. Biosph. 40, 253–272 (2010).

Regione Emilia-Romagna. Cartografia geologica on-line in scala 1:10.000 della Regione Emilia-Romagna. http://geoportale.regione.emilia-romagna.it/it/mappe/informazioni-geoscientifiche/geologia/carta-geologica-1-10.000. (2018).

Servizio geologico sismico e dei suoli. Sito della cartografia geologica del Servizio Geologico, Sismico e dei Suoli, Regione Emilia-Romagna, Assessorato Difesa del Suolo e della Costa. Protezione Civile. https://applicazioni.regione.emilia-romagna.it/cartografia_sgss/user/viewer.jsp?service=geologia. (2018).

Acknowledgements

Massimo Tonelli, Mauro Zapparoli, Fabio Bergamini (CIGS, Modena), Danilo Bersani (Università di Parma), Nicolas Rividi and Michel Fialin (CAMPARIS, Paris) are thanked for their help during data acquisition. This research was supported by PNRA (PdR 2016_00245), the Preistoria Attuale Foundation, the Deep Energy community of the Deep Carbon Observatory awarded by Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, the deepOASES ANR project (ANR-14-CE01-0008-01), the French CNRS (Mission pour l’Interdisciplinarité, Défi Origines 2018), the Italian PRIN (prot.2015C5LN35) and the Marie Curie Cofund Program at the University of Liège. This is IPGP contribution n° 3970.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.C.S., D.B., C.P., V.P., D.M., B.M. acquired and treated the data. M.C.S, D.B. and B.M. wrote the paper with input from all the co-authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sforna, M.C., Brunelli, D., Pisapia, C. et al. Abiotic formation of condensed carbonaceous matter in the hydrating oceanic crust. Nat Commun 9, 5049 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07385-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07385-6

This article is cited by

-

The rocky road to organics needs drying

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Soluble organic matter Molecular atlas of Ryugu reveals cold hydrothermalism on C-type asteroid parent body

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Decoupling of inorganic and organic carbon during slab mantle devolatilisation

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Challenges in evidencing the earliest traces of life

Nature (2019)

-

Pyrite and Organic Compounds Coexisting in Intrusive Mafic Xenoliths (Hyblean Plateau, Sicily): Implications for Subsurface Abiogenesis

Origins of Life and Evolution of Biospheres (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.