Abstract

Shapes of edible plant organs vary dramatically among and within crop plants. To explain and ultimately employ this variation towards crop improvement, we determined the genetic, molecular and cellular bases of fruit shape diversity in tomato. Through positional cloning, protein interaction studies, and genome editing, we report that OVATE Family Proteins and TONNEAU1 Recruiting Motif proteins regulate cell division patterns in ovary development to alter final fruit shape. The physical interactions between the members of these two families are necessary for dynamic relocalization of the protein complexes to different cellular compartments when expressed in tobacco leaf cells. Together with data from other domesticated crops and model plant species, the protein interaction studies provide possible mechanistic insights into the regulation of morphological variation in plants and a framework that may apply to organ growth in all plant species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Remarkable phenotypic diversity characterizes cultivated fruits and vegetables. Thousands of years of selection under cultivation have allowed for the accumulation of mutations that collectively comprise modern day germplasm. This diversity is critical for the successful marketing of a wide array of plant species, from food crops to ornamentals. Utilizing morphologically diverse domesticated germplasm also leads to a better understanding of fundamental growth processes common to all higher plants. Coordinated cell division and expansion patterns regulate the shape and size of plant organs. Specifically, the rate, duration and plane of cell division, as well as isotropic and anisotropic cell enlargement contribute greatly to final morphology of plant organs1. Recent studies have revealed several genes that control the growth form of agriculturally important organs, such as fruits and seeds2,3. One of the most commonly utilized tomato fruit shape gene is OVATE4, the founding member of the OVATE Family Protein (OFP) class5. A mutation in OVATE usually leads to an elongated fruit, yet the extent of elongation varies depending on the genetic background6. Shape regulation of the aerial parts in Arabidopsis and grain shape in rice is controlled in part by LONGIFOLIA1 and LONGIFOLIA27,8,9,10, members of the TONNEAU1 Recruiting Motif (TRM) family11. Whether OFPs and TRMs function in the same developmental pathway to regulate organ shape and whether orthologous members in other plants share similar functions is unknown. Moreover, the biochemical function and the impacts of the encoded proteins at the cellular and tissue-specific levels are poorly understood. Thus, gaining insights into the function of these proteins in developmental processes related to shape determination will be key to understanding the remarkable morphological diversity observed in plant organs within and among species.

Herein we fine-map and clone a suppressor of ovate (sov1), which encodes another member of the OFP class. The altered shape is due to changes in cell number in the ovary, which implies a shift in cell division patterning during development of the organ. OVATE-interacting proteins, identified by the yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) approach, include 11 members of the tomato TRM family. We show that conserved charged amino acid residues in the interacting motifs are necessary for the protein-protein interaction. Upon co-expression in Nicotiana benthamiana epidermal leaf cells, the protein complexes relocalize subcellularly to the cytosol or to microtubules depending on the OFP and TRM combination. Using CRISPR, a knock out mutation in tomato TRM5 rescues the fruit shape phenotype in the ovate/sov1 double mutants. We also demonstrate that members of the same OFP and TRM subclades are associated with natural variation of melon and cucumber fruit as well as potato tuber shape. These results integrate the previous knowledge on OFPs and TRMs, and provide possible mechanistic insights into organ shape regulation in higher plants.

Results

Fine-mapping and cloning of SlOFP20

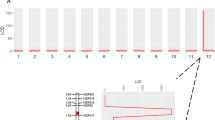

The mutant allele of ovate is common in cultivated tomato and usually leads to an elongated fruit shape6. Tomato accessions carrying ovate may produce oval, rectangular or pear shaped fruit, and a few produce fruit with a pointed tip. In rare cases, ovate accessions produce fruits of a near perfect round shape6. These variable tomato fruit shapes suggest the presence of modifier loci in the germplasm, and knowledge of the underlying genes would provide insights into the regulation of morphological diversity. As a step toward identifying critical genes in the OVATE fruit shape pathway, we mapped one modifier locus on chromosome 10 that we refer to as suppressor of ovate (sov1)12. Further fine-mapping of the locus identified a 149.7-kb region (Supplementary Table 1; Fig. 1a) that carries three annotated genes, Solyc10g076170, Solyc10g076180 and Solyc10g076190. The gene Solyc10g076180 corresponds to another member of the OFP class, SlOFP20, which was highly expressed in flowers at anthesis (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Of these three genes, only SlOFP20 was consistently differentially expressed in near isogenic lines (NIL) polymorphic at the sov1 locus (Fig. 1b), suggesting that this gene might control fruit shape. Investigations into allelic diversity at sov1 showed a 31-kb deletion in the upstream regulatory region of SlOFP20 6.5 kb away from the transcription start site, which may be the cause of the reduced expression of the gene (Fig. 1a; Supplementary Fig. 2). The other candidate genes were either not differentially or extremely low expressed, or encoded for an unknown protein, and therefore, were not pursued further.

Map-based cloning of SlOFP20. a The 149.7-kb sov1 locus on tomato chromosome 10. Markers are indicated in green. The physical positions in base pairs are labeled beneath markers and genes. b Expression levels of the three genes within the sov1 locus in anthesis-stage tomato flowers from the ovate and sov1 NILs. RPKM, reads per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads. c Effect of overexpression of SlOFP20 on fruits and leaves of Yellow Pear in two independent T0 transgenic lines. d Effect of down regulation of SlOFP20. The lines are BC1F2 from four independently transformed lines expressing two different artificial microRNAs (amiRNAs, a1 and a2) targeting SlOFP20. The error bars and letters in the graph indicate the standard errors among four plants and significant differences in fruit shape index evaluated by Tukey’s test (α < 0.05), respectively.+, wild type allele; -, mutant allele. The white and black bars represent 1 cm and 5 cm, respectively

To confirm that SlOFP20 is indeed underlying sov1, we overexpressed the gene in the Yellow Pear variety (Solanum lycopersicum L.) (Fig. 1c). Conversely, we reduced expression of the wild type SlOFP20 allele in the close wild relative of tomato, S. pimpinellifolium LA1589 to approximate the expression level in the NIL (Fig. 1b). The results showed that overexpression of SlOFP20 in Yellow Pear produced much rounder fruits than the non-transformed Yellow Pear as well as shortened leaves and rounder leaflets (Fig. 1c; Supplementary Fig. 3; Supplementary Data 1). Correspondingly, down regulation of SlOFP20 in LA1589 led to a more elongated fruit shape but only in the ovate background (Supplementary Data 2). Importantly, down regulation of SlOFP20 in the ovate background led to a tomato shape that was as elongated as or more elongated than the natural sov1/ovate double NIL (Fig. 1d). These plant transformation results conclusively show that SlOFP20 underlies sov1 and demonstrate that mutations in two OFP members contribute to natural fruit shape variation in the tomato germplasm.

OFPs and TRMs relocalize upon interaction

To determine the role of OFPs in fruit morphology, we identified interacting proteins using the Y2H approach. Using OVATE as the bait, we identified 185 interacting clones, of which 63.8% originated from 11 genes belonging to the TRM superfamily (Fig. 2a; Supplementary Table 2). Phylogenetic analysis showed that several subgroups represented OVATE-interacting tomato TRMs (Supplementary Fig. 4). TRMs function in assembling the TTP (TON1-TRM-PP2A) complex, and certain TRMs target this complex to microtubules11. The TTP complex is postulated to regulate the organization of microtubule arrays, and thus control cell division patterns and cell growth11,13,14. Based on the minimum interacting protein region, motif M8 was found in all OVATE-interacting SlTRMs, and conversely, SlTRMs without a predicted M8 motif were not recovered. This finding suggests that M8 is required for interaction with OVATE (Supplementary Table 3). Pairwise Y2H interactions of SlOFP20 and selected SlTRMs showed that several interacted with both OFPs, presumably through the conserved C-terminal OFP domain (Fig. 2d).

Interactions of SlOFPs and SlTRMs in yeast. a The 11 SlTRMs identified in the Y2H screen to interact with OVATE. The Predicted Biological Score (PBS) A-D represents the highest to lowest interaction confidence scores, respectively. The eight motifs are indicated by the colored boxes. The orange bar highlights the overlapping region of independent SlTRM clones that were identified in the screen. b Conserved amino acids in the OFP domain. The boxed regions indicate the in vitro mutagenized amino acids. c The consensus TRM M8 motif. d Interactions between wild-type and mutant SlOFPs and SlTRMs in yeast. The error bars indicate the standard errors among three colonies

To test whether the negatively charged residues in the OFP domain interact with the positively charged residues in the M8 motif of the OVATE-interacting TRMs, we performed Y2H assays with wild-type and mutant versions of the proteins (Fig. 2d; Supplementary Fig. 5). In general, mutations in conserved acidic residues in the OFP domain led to reduced or abolished Y2H interaction with different TRMs, whereas mutations in less conserved acidic residues did not change interactions in yeast with SlTRM compared to the wild-type allele (Fig. 2b, d; Supplementary Fig. 5). Conversely, mutations in the basic residue of the SlTRM M8 motif reduced the interactions with wild-type OVATE and SlOFP20 (Fig. 2c–d). Mutations of D280 in OVATE and the equivalent D265 in SlOFP20 most severely reduced or abolished the interactions with the TRMs. The responses of TRMs to OFP mutations differed, with SlTRM17/20a being less affected than SlTRM5, demonstrating in yeast the potentially dissimilar kinetics between the members of these two families. Together, these data validate the Y2H interactions and imply that the D280 residue in OVATE (D265 in SlOFP20) and the M8 K/R residues are most critical for protein-protein interactions between OFPs and TRMs.

To determine whether OVATE and SlOFP20 physically interact with SlTRMs in plant cells as they do in yeast, we expressed the proteins alone or together in pairs in tobacco (N. benthamiana) leaf epidermal cells. Many OFPs localize to the nucleus5,15, whereas TRMs localize in different subcellular locations including the cytoskeleton and cytoplasm11. The subcellular localization of OVATE and SlOFP20 was distinct as the former localized to the cytoplasm and the latter to the nucleus and cytoplasm (Fig. 3a–b). For the TRMs, we evaluated the subcellular localization of SlTRM5 and SlTRM17/20a, which are strong interactors with OVATE in yeast (Fig. 2d). When expressed alone, SlTRM5 associated with the cytoskeleton (Fig. 3c) whereas SlTRM17/20a was in the cytoplasm (Fig. 3d). The cytoskeleton interaction of SlTRM5 was most likely with microtubules as we observed a similarity in patterning with microtubule markers and the disruption of SlTRM5 subcellular localization in the presence of the microtubule-destabilizing agent Oryzalin (Supplementary Fig. 6). Henceforth, we consider the cytoskeleton-localized SlTRM5 to be a microtubule-associated protein. Regardless of the localization of the two OFP members, neither localized in the same compartment as SlTRM5 when expressed alone. To test the hypothesis that these proteins may relocate upon interaction, the OFPs and SlTRM5 were co-expressed in tobacco leaf cells. The results showed that SlTRM5 re-localized nearly exclusively to the cytoplasm when co-expressed with OVATE while the latter remained in the cytoplasm (Fig. 3e; Supplementary Fig. 7a). On the other hand, when co-expressed with SlOFP20, SlTRM5 remained associated with the microtubules in 71% of the cells (Fig. 3f; Supplementary Fig. 7a). Distinct from OVATE’s localization (Fig. 3e; Supplementary Fig. 7b), co-expression with SlTRM5 led to relocalization of SlOFP20 to the microtubules (Fig. 3f; Supplementary Fig. 7c). Mutants of OVATE, OFP20, and SlTRM5 that led to reduced or abolished interaction in yeast also greatly reduced the number of cells that showed relocalization of SlTRM5 when co-expressed with OVATED280R or SlOFP20D265R, and double mutants reduced relocalization of either SlOFP20 or SlTRM5 even further (Supplementary Fig. 7d-e). Similar results were obtained with another microtubule-associated TRM, SlTRM3/4 (Supplementary Fig. 8). When co-expressed with either OVATE or SlOFP20, SlTRM3/4 re-localized entirely to the cytoplasm, and similar decreases in relocalization were observed with mutant versions of OVATE (OVATED280R) and SlTRM3/4 (SlTRM3/4K560V). Bifluorescence Complementation (BiFC) assays further supported the interactions of OVATE and SlOFP20 with several TRMs (Fig. 3g–i; Supplementary Fig. 8g) including the subcellular location of these interactions in the cytosol or microtubules. Consistent with the co-localization experiments, the BiFC signal in the tobacco leaf cells was substantially reduced when co-expressing mutant versions of the proteins. In all, these results demonstrate that both SlOFPs and SlTRMs physically interact in plant cells and that this contact leads to relocalization of one or the other protein. Moreover, the interaction between specific OFPs and TRMs appears dynamic because of different relocalization patterns for each pair in the tobacco leaf epidermal cell system.

Interactions of SlOFPs and SlTRMs in N. benthamiana leaf epidermal cells. a–d Subcellular localization of OVATE, SlOFP20, SlTRM5, SlTRM17/20a, respectively. e Co-expression of OVATE and SlTRM5. f Co-expression SlOFP20 and SlTRM5. g–i BiFC with wild-type and mutant versions of SlOFPs and SlTRMs. On the left, an image of a single cell at 40× magnification demonstrating the subcellular localization of the interacting proteins. Black and white images on the right, an overview of signal intensity at 10× magnification. Scale bar, 20 μm

trm5 rescues ovate/sov1 by changing cell division patterns

To investigate the effect of the two tomato OFPs with SlTRMs on fruit shape in a common genetic background, we constructed NILs for the natural ovate and sov1 alleles and created mutations in the tomato TRMs that represent the TRM1–5 clade in Arabidopsis (Supplementary Fig. 4 and 9). The OVATE-interacting TRMs, SlTRM3/4 and SlTRM5 were the only members of this clade and, thus were pursued further. Moreover, gene expression analyses showed that among others, SlTRM5 was highly co-expressed with OVATE (Supplementary Fig. 1b). The natural sov1 NIL, carrying the mutation in the SlOFP20 promoter, produced fruit that was morphologically indistinguishable from wild type (Fig. 4a–b). The ovate NIL showed an increase in fruit elongation and degree of obovoid, and a decrease in proximal end angle, whereas the double NIL showed the strongest effect on fruit shape. Both mutant alleles were recessive and studies of epistasis showed a strong synergistic interaction between the two loci (Supplementary Table 4). Whereas the inactivation of SlTRM3/4 led to inconclusive results (Supplementary Fig. 10), the inactivation of SlTRM5 resulted in a slightly flatter fruit. Backcrossing Sltrm5–1 into the ovate/sov1 double NIL background resulted in greatly reduced fruit elongation, with shapes that were similar to wild-type fruits (Fig. 4a, b; Supplementary Table 5). Another inactivation allele, Sltrm5–2, showed similar results as Sltrm5–1 (Supplementary Fig. 11). Therefore, Sltrm5 complements fruit shape in the ovate/sov1 background.

Complementation of fruit and ovary elongation by Sltrm5 in the ovate/sov1 background. a Mature fruits of the ovate/sov1/Sltrm5 single, double and triple NILs. o, ovate; s, sov1; t5-1, Sltrm5-1. b Comparisons of mature fruit traits among the ovate/sov1/Sltrm5 NILs. Fruit shape index is the ratio of length to width; proximal end angle is the angle of the fruit at 10% from the very top of the fruit; obovoid is the area below the mid-point of the fruit. c Ovary shape index at anthesis in the different NILs. d Propidium Iodine staining of anthesis-stage ovaries (left) and cell sizes in the proximal end of anthesis ovaries (right). The proximal area of an ovary is indicated by the yellow outline of the box and refers to the length and width traits measured in e. e Histological and cellular evaluations of the proximal end of anthesis ovaries in the different NILs. The letters in the boxplots indicate the significant differences among different genotypes evaluated by Duncan’s test (α < 0.05). The lower and upper bounds of the box in a boxplot indicate the first and third quartiles, respectively. The median and outliers are indicated by the center line and dots, respectively. The scale bars for fruit, ovary, and cell morphology represent 1 cm, 0.5 mm, and 50 μm, respectively

To determine whether these mutations exert their effects during either ovary or fruit development, we investigated ovary shape at flower opening. All mutants, including sov1 and Sltrm5, showed significant ovary shape changes at anthesis (Fig. 4c; Supplementary Table 5). The most significant morphological changes appeared at the proximal end of the ovary, away from the ovules. This area expanded strongly in the proximo-distal direction in the ovate and ovate/sov1 mutants and returned to the wild-type phenotype in the ovate/sov1/Sltrm5 mutant (Fig. 4c–e; Supplementary Table 5). To reveal the mechanisms that underlie the histology of shape, cellular parameters at the proximal end of the anthesis-stage ovaries were characterized. In the ovate and ovate/sov1 genotypes, cell number increased significantly along the proximo-distal axis and decreased significantly along the medio-lateral axis. These cell number changes were offset in the presence of Sltrm5, resulting in cell numbers that approximated the values found in wild-type ovaries, especially in the proximo-distal direction (Fig. 4e; Supplementary Table 6). Cell length and width also increased in ovate and ovate/sov1, and Sltrm5 rescued these traits in these mutant backgrounds. However, cell shape indices were highly variable and barely altered compared to wild-type, suggesting a minor role for cell elongation in regulating ovary length. Together, these data show that OVATE and SlOFP20 synergistically function in shape regulation by primarily modulating cell division patterns. The critical cell division patterns occur during floral development and perhaps as early as when carpel primordia arise. SlTRM5 balances the OVATE and SlOFP20 division patterns to determine final tomato shapes. Combined with the protein localization patterns in tobacco, our data suggest that the relocalization of the OFP-TRM protein complexes are critical to fine tune cell division patterns early in development, thereby ultimately controlling fruit shape. However, these protein relocalizations would have to be further investigated in growing organ primordia of the plant.

A common pathway regulating plant organ shapes

Whereas the effects of natural allelic variation in tomato TRMs are unknown, ovate and sov1 have a strong impact on fruit shape in the NILs (Fig. 4a). To determine when the ovate and sov1 alleles arose, we evaluated their presence in ancestral populations that were collected in Peru and Ecuador (first domestication site), and Mexico (second domestication site)16. The data showed that ovate and sov1 arose in the ancestral semi-domesticated germplasm of tomato, and that both mutant alleles were found in low frequency, yet never in the same accession that resulted from these early domestication events (Fig. 5a). We determined whether both mutations are required for obovoid shape in modern day tomatoes. The data showed that the mutant alleles at these loci combined after initial domestication since every ovate/sov1 accession produced obovoid fruits (Fig. 5b, c; Supplementary Data 3). Obovoid accessions that only carried the mutation at ovate were equally elongated in shape but showed a reduced degree of obovoid, and an increase in proximal end angle as well as eccentricity (Fig. 5d). Combined, these morphological attributes demonstrate that most extreme obovoid tomato fruit requires mutations in both OVATE and SlOFP20.

Distribution of sov1 and ovate in tomato germplasm and its impact on fruit morphology. a Frequency of ovate and sov1 in an ancestral population of tomato. SP ECU, Solanum pimpinellifolium accessions from Ecuador; SP PER, Solanum pimpinellifolium accessions from Peru; SLC ECU, Solanum lycopersicum var. cerasiforme accessions from Ecuador; SLC PER, Solanum lycopersicum var. cerasiforme accessions from Peru, SLC CAm, Solanum lycopersicum var. cerasiforme accessions from Central America; SLL MEX, Solanum lycopersicum var. lycopersicum accessions from Mexico. The number of accession in each category is indicated in parentheses. b Shape of fruits from cultivated tomato accessions carrying both the ovate and sov1 mutations. The scale bar represents 1 cm. c Frequencies of ovate and sov1 in different tomato shape categories in percentage based on the number of accessions in the category. Shape categories are: obovoid (Ob), ellipsoid (El), rectangular (Re), heart (He), long (Lo), round (Ro), oxheart (Ox) and flat (Fl), respectively. d Variation among fruit shape traits of obovoid fruits for cultivars carrying ovate or ovate/sov1 mutations. The p value represents the result of the student’s t-test between groups

Our results clearly demonstrate the critical role of two OFP proteins in regulating tomato fruit shape by changing cell division patterns early in the development of the organ. The role of OFPs in regulating the shapes of other plant organs and in other species is less clear. Melon (Cucumis melo) fruits are morphologically diverse and several QTLs associated with shape have been identified17,18. We fine-mapped the fruit shape QTL fsqs8.1 in a population derived from a cross between Piel de Sapo and PI124112, to a 152 kb segment on melon chromosome 8 carrying just six candidate genes including CmOFP13 (Fig. 6a; Supplementary Table 7). In cucumber (Cucumis sativus), a species closely related to melon, the fruit shape QTL fs3.2 interval contains CsOFP15, a gene that is lower expressed in cucumber varieties with an elongated fruit19. This is expected if CsOFP15 controls cucumber fruit shape. Tuber shape in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) and its wild relatives (Solanum section Petota) varies from very round to long and narrow such as in fingerling varieties. The tuber shape QTL Ro has been fine-mapped in an outcrossing F1 population to a region on potato chromosome 10 that appears syntenic to the tomato chromosome region encompassing SlOFP2020,21 (Fig. 6b; Supplementary Table 8). However, the ortholog of tomato OFP20 is not present in the genome of potato DM1–3 at this location. On the other hand, a round tuber parent, M6, carries an ortholog of SlOFP20 (Fig. 6b). Using a diploid potato F2 population derived from a cross between the round tuber parent, M6 and the parent producing elongated tubers, DM1–3, showed a strong association with the StOFP20 marker suggesting that the gene is controlling tuber morphology in this population (Fig. 6b; Supplementary Fig. 12a)22. Mapping the DM1–3 genomic reads to the M6 genome showed a deletion of approximately 30 kb in DM1–3 including StOFP20 (Supplementary Fig. 12b), explaining the absence of this gene in the DM1–3 reference genome of potato. These data support the notion that potato tuber shape mapped to the Ro locus is controlled by the ortholog of tomato OFP20. OFPs also impact the shape of other organs. Overexpression of AtOFP1 in Arabidopsis leads to shorter leaves and floral organs5, which is similar to overexpression of SlOFP20 in tomato leading to rounder leaflets and shorter leaves (Fig. 1c). Thus, OFPs regulate shapes of many if not all organs in plants.

Association of OFP and TRM in regulating fruit and tuber shape in domesticated crops. a Fine-mapping of fsqs8.1 in melon to CmOFP13. Fruit shapes of the parental lines and the CALC8-1 NIL that carries the PI124112 allele of fsqs8.1 in the Piel de Sapo background. Scale bar, 5 cm. b Association of tuber shape with StOFP20 in potato. 1, homozygous DM1-3 allele; 2, heterozygous; 3, homozygous M6 allele. The green lines connect the syntenic orthologous gene pairs in tomato and the two potato accessions around SlOFP20. Scale bar, 1 cm. c Fine-mapping of the cucumber fs2.1 locus. The LOD curve from the cucumber F2 population led to candidate gene identification including CsTRM5, an ortholog of SlTRM5. Likely candidate genes are denoted in red. Other gene annotations are denoted in blue. Scale bar, 2.5 cm

In tomato, we showed that the null mutation in SlTRM5 genetically interacted with ovate and sov1 to suppress the phenotype to a round shape primarily by reducing cell division in the proximo-distal direction. In cucumber, a population derived from a cross between WI7238 and WI7239 carrying long and round fruit, respectively, led to the identification of two fruit shape QTL, fs1.2, and fs2.123. We fine-mapped the cucumber fruit shape QTL, fs2.1 to 10 candidate genes including an ortholog of AtTRM5/SlTRM5 (Fig. 6c; Supplementary Table 9). Mutations in GL7/GW7 encoding a rice TRM that belongs to the Arabidopsis TRM1–5 (LONGIFOLIA) clade (Supplementary Fig. 13a) affects grain shape by changing cell division and cell elongation patterns8,9,10. Additionally, overexpression or loss-of-function mutants of AtTRM1 and AtTRM2 in Arabidopsis produce elongated or shortened siliques and leaves, respectively, resulting from altered cell elongation7,11. In addition to fruit shape, Sltrm5 also features rounder leaflets (Supplementary Fig. 11b), producing shapes that are similar as found in SlOFP20 overexpressors (Fig. 1c). The results suggest that collectively certain TRMs control cell number and/or cell shape, and influence organ shapes in a similar manner as certain OFPs. Intriguingly, most of the genetically identified OFPs and TRMs that control plant organ shape fall in the Arabidopsis OFP1–5 and TRM1–5 clades respectively (Supplementary Fig. 13). This finding implies that orthologous members of these subclades are likely involved in regulating organ morphology in many other plant species.

Discussion

In addition to providing evidence that OFPs and TRMs control fruit, tuber, vegetable, and grain shapes in domesticated plants and were the targets of selection, our findings uncovered a link between these two families which are common in genomes of multicellular plants11,24. This finding extends to other plant parts such as leaves and floral organs in model and crop plants, and span both eudicot and monocot species. A model for genetic mechanism of OFPs and TRMs in organ formation implies that their relative expression levels are critical to control the eventual shape of plant organs (Fig. 7). We propose that the balance between subcellular localization of the protein complexes, e.g., in the cytoplasm or associated with microtubules, may determine the growth patterns underlying organ shape. Moreover, the relocalization of OFPs and TRMs to different subcellular compartments upon interaction suggests that a dynamic balance between cytoplasmic-localized and microtubular-localized OFP-TRM protein complexes may regulate cell division and growth early in development of the organs. These results offer opportunities for plant breeders to target selection and/or genome editing approaches to create varieties for niche markets as well as for crop improvement in general. In addition, the apparent universality of the OFP-TRM module is likely to be part of a network required for coordinated multicellular growth in all plants.

The OFP-TRM module that regulates plant organ shape. The natural derived allele of OVATE, a true null, and the natural derived allele of SlOFP20, a deletion in the upstream regulatory region proposed to reduce expression of the gene, result in pear-shape tomato fruit. A CRISPR-Cas9 induced frame shift mutation in SlTRM5 rescues the fruit shape phenotype to a nearly round fruit. In general, the TRM1–5-like genes promote the elongation of fruit, grain, leaf and tuber, whereas OFP1-like genes play an antagonistic role

Methods

DNA sequencing and marker development

DNA was extracted from Yellow Pear (YP) and Gold Ball Livingston (GBL) leaf samples using the Qiagen kit (Germantown, MD) and following manufacturer’s instructions. DNA libraries were constructed and sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq2000 platform with the 101-bp paired-end mode at the Genome Technology Access Center (GTAC) at Washington University, St Louis MO (SRA SRP127270). After removing adapters and low-quality sequences, the sequences represented more than 20× coverage of the genome (aligned bases divided by 950 Mbp length of the tomato genome). High quality cleaned reads were aligned to the tomato genome SL2.4025 using NovoAlign (http://www.novocraft.com/). SNPs were identified in the genomic regions of interest using SAMtools26. High quality (>100) homozygous SNPs with coverage higher than 15× were kept for marker development. Based on the identified SNPs, we developed 26 additional dCAPS markers located between the existing markers, 12EP153 and 12EP5 (Supplementary Data 4) using dCAPS Finder (http://helix.wustl.edu/dcaps/dcaps.html) and Primer 3 (http://bioinfo.ut.ee/primer3-0.4.0/). The sov1 deletion in the promoter of SlOFP20 was identified by aligning the reads of the YP and GBL to the reference genome (Supplementary Fig. 2). After validation by Southern blotting, the structural rearrangement was further validated using primers 13EP549, 13EP550 and 13EP551 in a single PCR reaction. The wild-type band runs at 1220 bp whereas the fragment that amplifies YP DNA runs at 900 bp. The Heinz 1706 BAC clone sequence, LE_HBa0040P16 containing SlOFP20 (Genbank AC244530) allowed us to estimate the size of the sov1 deletion to 31 kb and its position in relation to the coding region of SlOFP20. The estimation of putative transcription start site of SlOFP20 is based on the tomato ESTs and cDNAs database (https://solgenomics.net/) as well as our RNA-seq data (SRA SRP090032; SRP089970).

Potato StOFP20-trait association

The M6 potato genome scaffold 814 harbored the ortholog of SlOFP2027. Primers were designed to amplify the ortholog in M6 and a linked sequence in DM1–3 (Supplementary Data 4). The marker was genotyped using 190 individuals of a segregating F2 population derived from DM1–3 and M622. ANOVA analyses were applied to determine the significance of the association of the marker allele with the phenotype.

Alignment of the potato DM1–3 reads to the M6 scaffold 814

Reads from the 16 paired-end genomic DNA libraries of potato DM1–3 used in the de novo assembly of the reference genome (SRA029323) were aligned to M6 scaffold 814 using BWA-MEM v0.7.1328 in paired-end mode with default parameters. Alignments with MAPQ score higher than or equal to 30 were kept and visualized with Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV v2.3.68).

Overexpression of SlOFP20

Full length SlOFP20 was amplified from DNA using primers 13EP617/618 (Supplementary Data 4) and Phusion® high-fidelity DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA). The fragment was cloned into the XhoI/SacI site of the pKYLX71 vector29 and expressed under the 35S promoter. The construct was sequenced to confirm that no errors were introduced during the amplification and then transformed in YP. Five independent transgenic lines were obtained and fruit and leaf shape analysis was done using 8 mature fruits or primary leaflets of each plant.

Downregulation of SlOFP20

Two artificial microRNAs (amiRNAs) targeting the coding region of SlOFP20 were designed using the WMD3 Web MicroRNA Designer (http://wmd3.weigelworld.org/) and put into the Arabidopsis MIR319a precursor backbone. The sequences of amiRNAs designed to knock-down the expression of SlOFP20 were provided in Supplementary Data 4. The engineered amiRNA precursors were synthesized at GenScript Biotech Corporation (Piscataway, NJ) and then cloned into the SacI/XbaI site of the pKYLX71 vector29. The two SlOFP20 amiRNA constructs were transformed in LA1589 resulting in 12 primary transgenic lines. The T0 lines were evaluated for downregulation of SlOFP20 using semi-quantitative PCR. Two of the most down regulated lines per construct were backcrossed to SA29 carrying the ovate mutation. The resulting seedlings were selected for the presence of the transgene using primers EP553/554 (Supplementary Data 4) and selfed to produce families 15S91, 15S92, 15S93, and 15S94 (BC1F2).

SlTRM CRISPR/Cas9 mutants

A CRISPR/Cas9 construct was designed to create mutations in both SlTRM3/4 and/or SlTRM5. The construct was assembled using the Golden Gate cloning method30. Two sgRNAs specifically targeting each of the two SlTRMs were amplified using the pICH86966::AtU6p::sgRNA_PDS construct (Addgene plasmid #46966, www.addgene.org) as a template with the reverse primer: 13EP639 and forward primers: 14EP292 and 14EP294 for SlTRM3/4 and SlTRM5, respectively (Supplementary Data 4). The level 1 constructs pICH47751 (Addgene #48002) and pICH47761 (Addgene #48003) were assembled using the level 0 construct pICSL01009::AtU6p (Addgene #46968) and the sgRNA PCR products to place each sgRNA under the Arabidopsis U6 promotor. Level 1 constructs, pICH47732::NOSp::NPTII (Addgene #51144), pICH47742::35S::Cas9 (Addgene #49771), pICH47751::AtU6p::sgRNA-SlTRM3/4, pICH47761::AtU6p::sgRNA-SlTRM5 and the linker pICH41780 (Addgene #48019) were then assembled into the level 2 vector pAGM4723 (Addgene #48015). All the vectors for building the CRISPR-Cas9 construct were provided by Vladimir Nekrasov and Sophien Kamoun, The Sainsbury Laboratory, Norwich Research Park, Norwich, UK.

Plant transformation and genotyping

Constructs were transformed into tomato at the Plant Transformation Facility at University of California (Davis, CA 95616) (amiRNA and overexpressor constructs), and by Dr. Joyce Van Eck, Cornell University (CRISPR-Cas9 constructs). The lines overexpressing or under-expressing SlOFP20 were genotyped for the presence of the construct with primers designed to amplify the NPTII gene conferring kanamycin resistance (EP553/554; Supplementary Data 4). For the CRISPR-Cas9 constructs, we received 16 independent T0 lines. By sequence analyses, the majority were found to carry mutations in both SlTRM3/4 and SlTRM5 and occasionally mutations were in both alleles of one or both genes. Most lines were sterile (male and female) as no fruits with seeds were generated by selfing or with wild type pollen onto mutant styles or mutant pollen unto wild type styles. The primary transformants that were fertile (four T0 lines) carried an in frame deletion (multiples of 3) and wild type allele for SlTRM3/4 and an in frame or frameshift mutations for SlTRM5. These fertile lines were crossed to LA1589 in order to remove the Cas9 transgene and stabilize the lines. Once stabilized, for SlTRM5 the 1 bp deletion and 1 bp insertion alleles (causing a frameshift mutation and likely a null) were backcrossed into the sov1/ovate background, which is described above for the development of the NILs.

Fruit shape analysis

Full size maturing fruits were cut longitudinally, scanned at 300 dpi, and analyzed using Tomato Analyzer v3.031,32. The following attributes were measured in most samples: fruit shape index, proximal end angle, proximal eccentricity and obovoid, which measures the pear-shapedness. Fruit Shape Index is the ratio of the maximum height length to maximum width of a fruit. Proximal end angle is the angle between best-fit lines drawn through the fruit perimeter on either side of the proximal end point at 10% (NILs) or 20% (tomato varieties). Proximal eccentricity is the ratio of the height of the internal ellipse (defined by the section of the fruit where the seeds are located) to the distance between the bottom of the ellipse and the top of the fruit. Obovoid is calculated as the maximum width (W), the height at which the maximum width occurs (y), the average width above that height (w1), and the average width below that height (w2) are calculated and a scaling function scale_ob is used for calculation: Obovoid = 1/2 × scale_ob (y) × (1 – w1/W + w2/W), if obovoid > 0, subtract 0.4; otherwise, obovoid is 0. For the potato tuber shape analyses, length and width were measured in Image J and shape index was calculated by taking the ratio of these two measurements. The length of the curved potatoes was measured by tracing the curve. Melon Fruit Shape Index was calculated with Tomato Analyzer 3.0 from scanned images. For the cucumber shape analyses, length and width were measured with calipers and the shape index was calculated by taking the ratio of the two.

Ovary shape analysis

Anthesis ovaries were cut longitudinally and digitalized using the Olympus Szx9 (SZX-ILLB2–100) dissecting scope. The maximum length and width of ovaries were measured using ImageJ software (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/), and from this, the ratios of the maximum length to maximum width were calculated. Three to five plants of each genotype were analyzed, and the average values each taken from 8 to 10 fruits or ovaries per plant were analyzed with Tukey’s HSD test (α < 0.05).

Cellular attributes

Anthesis ovaries were cut longitudinally with a razor blade and fixed in FAA (50% Ethanol, 10% Formaldehyde, 5% glacial acetic acid) at 4 °C overnight. The samples were dehydrated on ice with ethanol-ddH2O series (50, 70, 85, 95, 100% x 2), and rehydrated with ethanol-ddH2O series (95, 85, 70, 50, 30, 15%) at one hour for each step. The samples were rinsed with ddH2O twice for 20 min each. Ovaries were incubated on ice in the staining buffer (0.02 mg/ml propidium iodide, (MP Biomedicals), 0.02% DMSO) for 1 h and rinsed with ddH2O for 20 min twice, then dehydrated with ethanol-ddH2O series (50, 70, 85, 95, 100%) on ice, and 100% ethanol at room temperature overnight. Finally, the samples were treated with 1:1 ethanol: methyl salicylate for 1–2 h followed by 100% methyl salicylate (Fisher Chemical) at 4 °C for 2–3 days. The sections were imaged using a Zeiss LSM 510 META Confocal Microscope, and cell size and number assessments were made using the ImageJ software package. The proximal area of the ovary (the area above the ovules closest to the stem end of the flower) was used for the histological and cellular analysis. The length and width of the entire proximal area was measured. Numbers of parenchyma cells were counted in the middle of the proximal area in both the proximo-distal and medio-lateral direction. The length and width of parenchyma cells in the proximal area were evaluated on at least 20 cells.

Yeast two-hybrid analyses

Full-length OVATE or full length SlOFP20 were cloned into the pGBKT7 vector (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) as C-terminal fusions to the GAL4 DNA binding domain (BD). Fragments of SlTRM5, SlTRM17/20a and SlTRM25 were cloned into the pP6 vector (Hybrigenics, Paris, France) as a C-terminal fusion to the GAL4 activation domain (AD). A pair of bait and prey plasmids were transformed into the Y2HGold yeast strain following the Clontech Yeast Protocol Handbook instructions (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) and plated on minimal medium lacking Trp and Leu (SD/-Trp/-Leu) with X-α-Gal (the substrate of MEL-1 gene product, α-galactosidase). Quantification of reporter α-galactosidase activity was performed using the Clontech Yeast α-Galactosidase Assay Kit. Three single colonies of each combination were grown in liquid synthetic dropout medium lacking leucine and tryptophan at 30 °C with shaking (250 cycles/min) for 18 h. After recording the OD600, the supernatants were collected via centrifugation at 18,800xg for 2 min. After adding the assay buffer (PNP-α-Gal + CH3COONa) to the supernatants and incubating at 30 °C for 60 min, the reaction was terminated by adding the stop solution (Na2CO3). The optical density of each sample was recorded at OD410 and α-galactosidase activity was calculated using the formula: 1,000 × Vf × OD410/[(e × b) × t × Vi × OD600] where t = time (min) of incubation, Vf = volume of assay (200 or 992 µl), Vi = volume of culture medium supernatant added, OD410 = A410 of the reaction mix, OD600 = A600 of 1 ml of culture, e × b = p-nitrophenol molar absorbtivity at 410 nm × the light path (10.5 (ml/μmol) for 200-µl format = 16.9 (ml/μmol) for 1-ml format where b = 1 cm). The empty vector was used as the negative control.

Phylogenetic and protein motif analyses of TRMs

To retrieve all putative SlTRM proteins in tomato, full-length sequences of 34 Arabidopsis members of this family were used for BLAST similarity search against the International Tomato Annotation Group release 2.3 predicted proteins (ITAG 2.40) (http://solgenomics.net/) and Motif Alignment and Search Tool (MAST) search33, both at a cutoff E-value of 10−5. The MEME tool34 was used to define the conserved motifs with the following parameters: “nmotifs 8, minw 10, maxw 100, minsites 30, maxsites 120”. ClustalW was used for multiple sequence alignment procedures. The phylogenetic relationships among the all the TRMs in tomato and Arabidopsis were estimated with neighbor-joining method based on the p-distance (i.e., the phylogenetic distances were obtained by dividing the number of amino acid differences with the total number of sites compared) and 1000 bootstrap validation. The phylogenetic tree was visualized by FigTree (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/). Protein charge plot were generated by calculating the total charge of amino acids over a sliding window of 51 residues as described previously11.

Phylogenetic analysis of the SlOFP20 subclade

We retrieved the potato ortholog and closest paralogs (four total) by conducting reciprocal best BLAST hits. This led to four OFP members in the M635 and doubled monoploid Group Phureja clone DM1–3 516 R44 (DM)36,37. The four hits in each potato assembly with the lowest E-value statistic were identified as initial candidate sequences. In order to find the best full-length tomato protein BLAST hits of each potato candidate sequence, the amino acid sequence returned for each hit was used as query in a BLASTp search against the SL3.0 tomato annotated protein sequences. Reciprocal best BLAST hit analysis was performed using these full-length tomato proteins. Each full-length protein was used as query in tBLASTn searches against the DM1–3 and M6 assemblies. The best DM1–3 and M6 hits from each of those searches was then used as query in reciprocal BLASTp and tBLASTn searches against the tomato protein sequences and genome SL3.0 assembly respectively, in order to identify and confirm each reciprocal best BLAST hit relationship. BLAST searches used the BLOSUM62 scoring matrix and a word size of 11 amino acids. Using similar methods, we obtained the five Arabidopsis OFP1 through OFP5 and the four melon OFP proteins that showed the best BLAST hit relationship to members of the SlOFP20 subclade. We also included OVATE and its best BLAST hit AtOFP7. The resulting reciprocal best BLAST hits were aligned with ClustalW. Phylogenetic relationships between them were estimated via the neighbor-joining method and p-distance, with the phylogeny rooted by the distant Physcomitrella OFP protein and validated with 1000 bootstraps, as implemented in Geneious 10.1.338.

Phylogenetic analysis of the AtTRM1–5 clade

We used the five Arabidopsis and three tomato proteins from Supplementary Fig. 4. We identified the rice and cucumber TRMs as described for the OFP1–5 clade. Phylogenetic analysis was implemented similarly as with the OFP reciprocal best BLAST hits, but with the phylogeny rooted by the Solyc02g089050 TRM protein.

In vitro mutagenesis

Site-directed mutagenesis of selected residues for SlTRMs and OVATE/SlOFP20 was carried out with the QuikChange II XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) according to the manufacturer’s specifications. Oligonucleotide primers between 25 and 35 bases with a melting temperature of ≥78 °C were designed using quikchange primer design software (http://www.genomics.agilent.com/primerDesignProgram.jsp) to cover the appropriate point mutations that would lead to the desired amino acids substitutions (Supplementary Data 4). The SlTRMs and OVATE/SlOFP20 mutants were subcloned into pP6 and pGBKT7 vectors respectively (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). Mutations were verified by DNA sequence analysis of the resulting clones.

Construction of plasmids for transient transformation

For constructs used in the transient assays, full-length wild type or mutant coding sequences (CDS) of OVATE, SlOFP20, SlTRM3/4, SlTRM5 and SlTRM25 were cloned into pENTR/D-TOPO Gateway entry vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The coding regions were recombined into binary destination expression vectors pH7RWG2 (Cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S promoter-driven) for C-terminal RFP (red fluorescent protein) fusions39,40 or pSITE-2CA and pSITE-2NA (2 × 35S) for N-terminal and C-terminal GFP (green fluorescent protein) fusions, respectively41. For the BiFluorescence Complementation (BiFC) experiments, full length wild-type OVATE and SlTRM25 were cloned as C-terminal or N-terminal fusions to the C-terminal or N-terminal fragment of the Yellow Fluorescent Protein (YFP) in the BiFC vectors pYN-1 (N-terminal fusion of YFP1–158), pYC-1 (N-terminal fusion of YFP159–238), p2YN (C-terminal fusion of YFP1–158) and p2YC (C-terminal fusion of YFP159–238)42 and co-expressed in all 8 combinations in N. benthamiana to determine the best usage of the BiFC vectors. Based on the overall YFP intensity and numbers of cells expressing YFP, the pYN-1 and p2YC vectors were used for SlTRMs and OVATE, respectively.

Transient expression of proteins in N. benthamiana

Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain C58C1 was used for the transient transformations. Colonies carrying the binary plasmids were grown at 28 °C on LB medium plates that contained 50 µg/ml gentamycin and 25 µg/ml rifampicin for selection of the strain, and 100 µg/ml spectinomycin for selection of the binary vectors, pH7RWG2 (carrying OVATE or SlOFP20 with a C-terminal RFP tag), pSITE-2CA (carrying SlTRM3/4 or SlTRM25 with a N-terminal GFP tag), and pSITE-2NA (carrying SlOFP20 with a C-terminal GFP tag)39,40,41. For agroinfiltration, single colonies were grown in liquid LB supplemented with gentamycin, rifampicin and spectinomycin overnight (28 °C, 220 cycles per minute). Fifty μl of the agro suspension was added to 5 ml LB with the same antibiotics for another overnight incubation under the same conditions. The agrobacteria were pelleted by centrifuging at 1610×g for 20 min or 2200×g for 15 min. The cells were resuspended in infiltration buffer containing 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM MES, PH 5.7 and 150 mM acetosyringone at pH 5.6 and adjusted to an OD600 of 0.2–0.3. The cells were incubated at room temperature for 3 h without shaking prior to infiltration. To enhance transient expression of the fusion proteins, the viral suppressor of gene silencing p19 protein was coexpressed in most of the experiments. For co-infiltration, equal volumes of cultures were mixed and infiltrated into N. benthamiana leaves through the abaxial surface using a 1-ml needleless syringe (Becton, Dickinson and Company). Plants were then kept in a growth room at 24/22 °C with a 16/8 h light/dark photoperiod for 48–72 h.

Epifluorescence and confocal microscopy

N. benthamiana leaf samples (approximately 0.25 cm2 near the infiltrated area) were collected at 70–90 h post-infiltration, mounted in water and viewed directly with a Zeiss LSM 880 confocal scanning microscope using an oil immersion objective 40× Plan-Apochromat 1.4NA (numerical aperture of 1.4). Fluorescence was excited using 488 nm and 543 nm light for GFP and RFP, respectively. GFP and RFP emission fluorescence was selectively detected at 490–540 and 550–630 nm using the Zen 2.3 SP1 software. For each experiment, 50–100 cells in two independent leaves that expressed both proteins were evaluated. For the BiFC experiments, YFP fluorescence was excited using 514 nm laser and detected at 520–550 nm using the Leica TCS SP5 confocal scanning microscope with a 25x objective.

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Raw sequence reads have been deposited into the DNA DataBank of Japan (DDBJ) under accessions SRP090032; SRP089970; SRA061767 for the mRNA seq data; and SRP127270 for the whole genome sequence data. The normalized expression data are also available at the Tomato Functional Genomics Database (TFGD; http://ted.bti.cornell.edu/) under the experiments D015 and D016. A Reporting Summary for this Article is available as a Supplementary Information file. Other methods can be found in the Supplementary Methods section in the Supplementary Information file.

References

van der Knaap, E. & Ostergaard, L. Shaping a fruit: Developmental pathways that impact growth patterns. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 79, 27–36 (2018).

Zuo, J. & Li, J. Molecular genetic dissection of quantitative trait loci regulating rice grain size. Annu. Rev. Genet. 48, 99–118 (2014).

Van der Knaap, E. et al. What lies beyond the eye: the molecular mechanisms regulating tomato fruit weight and shape. Front. Plant Sci. 5, 227 (2014).

Liu, J., Van Eck, J., Cong, B. & Tanksley, S. D. A new class of regulatory genes underlying the cause of pear-shaped tomato fruit. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 13302–13306 (2002).

Hackbusch, J., Richter, K., Muller, J., Salamini, F. & Uhrig, J. F. A central role of Arabidopsis thaliana ovate family proteins in networking and subcellular localization of 3-aa loop extension homeodomain proteins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 4908–4912 (2005).

Rodriguez, G. R. et al. Distribution of SUN, OVATE, LC, and FAS in the tomato germplasm and the relationship to fruit shape diversity. Plant Physiol. 156, 275–285 (2011).

Lee, Y. K. et al. LONGIFOLIA1 and LONGIFOLIA2, two homologous genes, regulate longitudinal cell elongation in Arabidopsis. Development 133, 4305–4314 (2006).

Wang, S. et al. The OsSPL16-GW7 regulatory module determines grain shape and simultaneously improves rice yield and grain quality. Nat. Genet. 47, 949–954 (2015).

Wang, Y. et al. Copy number variation at the GL7 locus contributes to grain size diversity in rice. Nat. Genet. 47, 944–948 (2015).

Zhou, Y. et al. Natural variations in SLG7 regulate grain shape in rice. Genetics 201, 1591–1599 (2015).

Drevensek, S. et al. The Arabidopsis TRM1-TON1 interaction reveals a recruitment network common to plant cortical microtubule arrays and eukaryotic centrosomes. Plant Cell 24, 178–191 (2012).

Rodriguez, G. R., Kim, H. J. & van der Knaap, E. Mapping of two suppressors of OVATE (sov) loci in tomato. Heredity 111, 256–264 (2013).

Spinner, L. et al. A protein phosphatase 2A complex spatially controls plant cell division. Nat. Commun. 4, 1863 (2013).

Schaefer, E. et al. The preprophase band of microtubules controls the robustness of division orientation in plants. Science 356, 186–189 (2017).

Yu, H. et al. Expression pattern and subcellular localization of the ovate protein family in rice. PLoS ONE 10, e0118966 (2015).

Blanca, J. et al. Genomic variation in tomato, from wild ancestors to contemporary accessions. BMC Genom. 16, 257 (2015).

Diaz, A. et al. Mapping and introgression of QTL involved in fruit shape transgressive segregation into ‘piel de sapo’ melon (cucumis melo l.) [corrected]. PLoS ONE 9, e104188 (2014).

Monforte, A. J., Diaz, A. I., Cano-Delgado, A. & van der Knaap, E. The genetic basis of fruit morphology in horticultural crops: lessons from tomato and melon. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 4625–4637 (2014).

Colle, M. et al. Variation in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) fruit size and shape results from multiple components acting pre-anthesis and post-pollination. Planta 246, 641–658 (2017).

Van Eck, H. J. et al. Multiple alleles for tuber shape in diploid potato detected by qualitative and quantitative genetic analysis using RFLPs. Genetics 137, 303–309 (1994).

Prashar, A. et al. Construction of a dense SNP map of a highly heterozygous diploid potato population and QTL analysis of tuber shape and eye depth. Theor. Appl. Genet. 127, 2159–2171 (2014).

Endelman, J. B. & Jansky, S. H. Genetic mapping with an inbred line-derived F2 population in potato. Theor. Appl. Genet. 129, 935–943 (2016).

Pan, Y. et al. Round fruit shape in WI7239 cucumber is controlled by two interacting quantitative trait loci with one putatively encoding a tomato SUN homolog. Theor. Appl. Genet. 130, 573–586 (2017).

Liu, D. et al. Phylogenetic analyses provide the first insights into the evolution of OVATE family proteins in land plants. Ann. Bot. 113, 1219–1233 (2014).

Consortium, T. G. The tomato genome sequence provides insights into fleshy fruit evolution. Nature 485, 635–641 (2012).

Li, H. et al. The sequence alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079 (2009).

Leisner, C. P. et al. Genome sequence of M6, a diploid inbred clone of the high glycoalkaloid-producing tuber-bearing potato species Solanum chacoense, reveals residual heterozygosity. Plant J. 94, 562–570 (2018).

Li, H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv:1303.3997v2 [q-bio.GN], (2013).

Schardl, C. L. et al. Design and construction of a versatile system for the expression of foreign genes in plants. Gene 61, 1–11 (1987).

Belhaj, K., Chaparro-Garcia, A., Kamoun, S. & Nekrasov, V. Plant genome editing made easy: targeted mutagenesis in model and crop plants using the CRISPR/Cas system. Plant. Methods 9, 39 (2013).

Rodriguez, G. R. et al. New features and many improvements to analyze morphology and color of digitalized plant organs are available in Tomato Analyzer 3.0 (2011). Proceedings of the 22nd Midwest Artificial Intelligence and Cognitive Science Conference Cincinnati OH.

Rodriguez, G. R. et al. Tomato Analyzer: a useful software application to collect accurate and detailed morphological and colorimetric data from two-dimensional objects. J. Vis. Exp. 16, 37 (2010).

Bailey, T. L. & Gribskov, M. Methods and statistics for combining motif match scores. J. Comput. Biol. 5, 211–221 (1998).

Bailey, T. L. & Elkan, C. Fitting a mixture model by expectation maximization to discover motifs in biopolymers. Proc. Int. Conf. Intell. Syst. Mol. Biol. 2, 28–36 (1994).

Hardigan, M. A. et al. Genome diversity of tuber-bearing Solanum uncovers complex evolutionary history and targets of domestication in the cultivated potato. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, E9999–E10008 (2017).

Paz, M. & Veilleux, R. E. Influence of culture medium and in vitro conditions on shoot regeneration in Solanum phureja monoploids and fertility of regenerated doubled monoploids. Plant Breed. 118, 53–57 (1999).

Xu, X. et al. Genome sequence and analysis of the tuber crop potato. Nature 475, 189–195 (2011).

Kearse, M. et al. Geneious Basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 28, 1647–1649 (2012).

Karimi, M., Inze, D. & Depicker, A. GATEWAY vectors for Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation. Trends Plant. Sci. 7, 193–195 (2002).

Karimi, M., De Meyer, B. & Hilson, P. Modular cloning in plant cells. Trends Plant. Sci. 10, 103–105 (2005).

Martin, K. et al. Transient expression in Nicotiana benthamiana fluorescent marker lines provides enhanced definition of protein localization, movement and interactions in planta. Plant J. 59, 150–162 (2009).

Yang, X. et al. Functional modulation of the geminivirus AL2 transcription factor and silencing suppressor by self-interaction. J. Virol. 81, 11972–11981 (2007).

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. David Bouchez and Martine Pastuglia (INRA, Versailles, France) for helpful discussions and suggestions. Jiheun Cho for greenhouse care and Jason Van Houten (Ohio State University) for technical support. Dr. Zhangjun Fei (USDA-ARS Ithaca NY) for helpful comments and suggestions. Drs. Wolfgang Lukowitz, Bob Schmitz and Kelly Dawe (University of Georgia) and Dr. Cris Kuhlemeier (University of Bern, Switzerland) for helpful comments on the manuscript. Funding for this research has been provided by National Science Foundation IOS 0922661, the Ohio State Tornado Recovery Fund OHOA0499, Ohio Agricultural Research and Development Center SEEDS grant 2014018, University of Georgia 1021RX070014, USDA AFRI National Institute of Food and Agriculture 2017-67013-26199 (EvdK). Ohio Agricultural Research and Development Center SEEDS grant 2014084 (SW). The Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness/FEDER grant AGL2015-64625-C2-2-R (AJM). The USDA AFRI National Institute of Food and Agriculture 2015-51181-24285 (YW). The USDA AFRI National Institute of Food and Agriculture 2014-67013-22434 (SHJ).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.W.: co-wrote the original draft, conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, validation and visualization. B.Y.: review and editing, formal analysis, methodology, investigation, validation. N.K.: review and editing, formal analysis, methodology, investigation, visualization, validation. G.R.R.: review and editing, formal analysis, investigation, visualization. H.J.K.: review and editing, formal analysis. M.C.: review and editing, methodology. EIB: review and editing, formal analysis, data curation. N.K.T.: review and editing, investigation, methodology, visualization. M.J.G.: review and editing, formal analysis. A.D.: review and editing, formal analysis. Y.P.: review and editing, formal analysis, investigation. C.L.: review and editing, sharing sequence data prior to publication. C.R.B.: review and editing, sharing sequence data prior to publication. D.H.: review and editing, formal analysis. Y.W.: review and editing, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation. S.H.J.: review and editing, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation. H.V.E.: review and editing, formal analysis, investigation, methodology. J.W.: review and editing, formal analysis, investigation, methodology. A.J.M.: review and editing, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation. T.M.: review and editing, formal analysis, methodology, investigation. E.vdK.: co-wrote the original draft, formal analysis, funding acquisition, conceptualization, investigation, project administration, supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, S., Zhang, B., Keyhaninejad, N. et al. A common genetic mechanism underlies morphological diversity in fruits and other plant organs. Nat Commun 9, 4734 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07216-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07216-8

This article is cited by

-

Enhancing cold resistance in Banana (Musa spp.) through EMS-induced mutagenesis, L-Hyp pressure selection: phenotypic alterations, biomass composition, and transcriptomic insights

BMC Plant Biology (2024)

-

Insights into Blossom End-Rot Disorder in Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum)

Plant Molecular Biology Reporter (2024)

-

Genomes of cultivated and wild Capsicum species provide insights into pepper domestication and population differentiation

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Characterization of gynoecious-parthenocarpic and monoecious cucumber lines (Cucumis sativus L.) and regression modelling to obtain high yielding and functionally rich genotypes

Horticulture, Environment, and Biotechnology (2023)

-

Design principles for synthetic control systems to engineer plants

Plant Cell Reports (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.