Abstract

Direct activation of carbon–fluorine bonds (C–F) to introduce the silyl or boryl groups and generate valuable carbon–silicon (C–Si) or carbon–boron (C–B) bonds is important in the development of synthetically useful reactions, owing to the unique opportunities for further derivatization to achieve more complex molecules. Despite considerable progress of C–F bond activation to construct carbon–carbon (C–C) and carbon–heteroatom (C–X) bond formation, the defluorosilylation via C–F cleavage has been rarely demonstrated. Here, we report an ipso-silylation of aryl fluorides via cleavage of unactivated C–F bonds by a Ni catalyst under mild conditions and without the addition of any external ligand. Alkyl fluorides are also directly converted into the corresponding alkyl silanes under similar conditions, even in the absence of the Ni catalyst. Applications of this protocol in late-stage defluorosilylation of potentially bioactive pharmaceuticals and in further derivatizations are also carried out.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Organic compounds that contain a carbon–fluorine (C–F) bond are attracting increasing attention due to their remarkable applications in pharmaceutical, agrochemical, and organic materials science, which arise predominantly from the intrinsic properties of fluorine (F)1. Numerous efforts have hence focused on the development of effective fluorination methods, significantly expanding the diversity of available F-containing compounds2. With the steady progress of methods for the preparation of organofluorine compounds, the activation of inert C–F bonds has recently drawn increasing attention, especially with respect to the effective derivatization of organic fluorine compounds3,4,5. Compared to the relatively activated C–X bonds of halogenated arenes and their equivalents (Ar–X; X = Cl, Br, I, OTf, or OMs), which easily undergo oxidative addition in metal-catalyzed coupling reactions, the cleavage of C–F bonds in fluoroarenes (Ar–F) is in general significantly more challenging due to their high bond dissociation energy; they are arguably the strongest bonds that carbon can form (Fig. 1a)6. Furthermore, the highly inert character of fluoroarenes renders them a more favorable platform for functionalization than any other reactive arenes Ar–X2. Moreover, a SciFinder search revealed that fluoroarenes are the largest group of commercially available halogenated arenes; the number of registered compounds is as follows; Ar–F (6,336,383), Ar–Cl (6,186,473), Ar–Br (3,407,354), and Ar–I (433,556). Thus, not surprisingly, significant research efforts have been directed toward C–F-cleavage protocols in order to develop synthetic strategies for complex aromatic compounds from ubiquitous fluoroarenes.

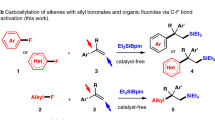

The bond strength and cross-coupling reaction via C–F cleavage. a Bond dissociation energies (BDEs); b Transition metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions for carbon–carbon and carbon–heteroatom bond-formations; c identification of defluorosilylation of unactivated fluoroarenes and alkyl fluorides under Ni catalyst or metal free

Efforts on transition-metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions of fluoroarenes have largely been confined to C–C bond-formation reactions (Fig. 1b, path a)7,8,9,10, while methods that employ fluoroarenes have been extended toward the formation of carbon–heteroatom bonds (C–X; X = NR2, OR, SR, BR2) (Fig. 1b, path b)11,12,13. One of the recent significant achievements in this area is the defluoroborylation independently reported by the groups of Martin and Hosoya; however, this method still is limited since it inevitably requires the use of electron-rich and expensive ligands such as phosphines or N-heterocyclic carbenes (NHCs), as well as relatively high temperatures (Fig. 1b, path b)14,15. Thus, the development of functionalization reactions for the inert C–F bonds of fluoroarenes under very mild conditions remains a challenge.

Organosilicon compounds have been extensively used in catalysis as well as a variety of other reactions as substrates and reagents. The straightforward functionalization of aryl and alkyl silanes by various organic transformations, such as the Hiyama coupling and Fleming–Tamao oxidation, is a fundamental research area. Organosilicon reagents, exemplified by trialkylsilyl cyanides (R3SiCN), azides (R3SiN3), ally silanes (R3SiCH2CH=CH2), and Ruppert–Prakash reagent (Me3SiCF3), are powerful tools for the direct-transfer functionalization of target molecules. The application of organosilicon compounds in organic electronics, photonics, and biologically active molecules for drug discovery has also been explored owing to their useful physicochemical properties. While a wide range of methods for the synthesis of organosilicon compounds have been developed, methods for the transformation of fluoroarenes into aryl silanes do not exist. Prompted by the versatility and pivotal role of organosilicon compounds16, as well as by our ongoing interest in the activation of inert C–F bonds17, we report herein an available example of the ipso-silylation of aryl and alkyl fluorides via cleavage of unactivated C–F bonds under catalytic conditions mediated by Ni or in the absence of metal catalyst (Fig. 1c). By means of this process, we have prepared a broad variety of aryl silanes and alkyl silanes. Since silicon and fluorine form one of the strongest bonds in organic chemistry (Si–F: 565 kcal/mol), the cleavage of C–F bonds using silylated reagents via formation of Si–F bonds is a very common strategy. Hence, the present method is an extremely rare example of a defluorosilylation reaction using silylated reagents.

Results

Optimization study

Initially, we chose 4-fluorobiphenyl (1a) as the substrate and a Ni catalyst to examine the C–F bond-cleavage reaction with the easily accessible silyl boronate 2a (Table 1; Supplementary Tables 1–7)18. Contrary to our initial expectation of the formation of an Aryl-Bpin compound, i.e., p-Ph-Ph-Bpin, we discovered that 1a was converted into silyl arene 3a (50% GC yield) using Ni(COD)2 (10 mol%; COD = cyclooctadiene), IPr·HCl (20 mol%), and NaOtBu (3 equiv) (toluene; temp = 110 °C; t = 24 h; Supplementary Table 1). The corresponding nucleophilic aromatic substitution (SNAr) product from NaOtBu was not observed either. Encouraged by this highly unexpected result, we decided to focus on this defluorosilylation of fluoroarenes. After screening the reaction conditions (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2), a moderate yield of 3a was obtained in the absence of an exogenous ligand (entry 1, Table 1). Even though NHC and phosphine ligands can be effective for the activation of C–heteroatom bonds under certain conditions14,15,19,20,21, such conditions did not work well for this transformation, even in the presence of additives such as CuF222, CuI14, LiCl19, or TMAF23 (Supplementary Table 2). We subsequently optimized the solvent system (entry 2, Table 1; Supplementary Table 3). Benzene and THF were equally effective as toluene for this reaction, while THF was better than the other solvents due to the suppression of hydrodefluorinated biphenyl as the main byproduct. Highly polar solvents such as 1,4-dioxane and DMF failed to provide 3a. Changing the solvent to cyclohexane furnished 3a in 74% yield. A binary solvent system (cyclohexane/THF = 1/2; v/v) afforded 3a in 89% yield at room temperature (entry 4, Table 1). Other ratios of this solvent system did not improve the reaction outcome (entries 3–5, Table 1). Further optimizations of the solvent, base, and metal catalyst are provided in Supplementary Tables 3–5. A reduction of the catalyst loading to 5 mol% Ni(COD)2 afforded a lower yield of 3a (Supplementary Table 5). The base KOtBu could be replaced with NaOtBu, KOMe, or KHMDS, albeit under concomitant reduction of the yield (entries 6–8, Table 1). As shown in entries 9 and 10, other Ni catalysts resulted in a significant decrease of the yield of 3a, similar to that observed with Cu-based catalysts (Supplementary Table 5). All reaction parameters were found to be critical for this in situ C–F bond cleavage with silylation reaction (entries 11 and 12, Table 1).

Substrate scope

With the optimal reaction conditions in hand (entry 4, Table 1), the scope of this ligand-free and mild Ni(COD)2-catalyzed silylation of fluoroarenes 1 was investigated (Fig. 2a). A wide range of π-extended fluoroarenes (1a–1l), fluorophenyls (1m–1w), fluoropyridines (1×, 1aa), and polyfluoroarenes (1aa–1cc) were efficiently converted into the corresponding aryl silanes (3a–3cc) using silylborane 2 as the coupling partner. Silylborane 2b furnished 3b in moderate yield under otherwise optimized reaction conditions. The chemoselectivity of this process is nicely illustrated by the fact that functional methoxy (3c, 3o), dioxole (3e), silyl ether (3t), phenoxyl (3q), amine (3r), and boronic ester (3v) groups, which could be potentially cleaved in the presence of the Ni(0) complex, remained intact under the applied conditions24,25,26. The steric hindrance of ortho-substituents was also tolerated, as shown by the formation of aryl silanes 3j and 3u. It should be noted that fluoroarenes bearing pyrrole, thiophene, or indole rings also participated in the reaction, furnishing the desired defluoroarylsilanes 3f, 3g, 3h, and 3k in good yield, without observation of the expected sp2 C–H bond activation–silylation products27.

Scope of the defluorosilylation reactions. a Defluorosilylation of fluoroarenes. Standard reaction conditions: 1 (0.2 mmol, 1 equiv), R3SiBpin (1.5 equiv), Ni(COD)2 (10 mol%), KOtBu (2.5 equiv), c-hexane/THF (1/2, v/v, 0.8 ml), rt, 2–12 h. Isolated yields. *Et3Bpin (1.1 equiv). b Defluorosilylation of fluoroalkanes. Standard reaction conditions: 4 (0.2 mmol, 1 equiv), Et3SiBpin (1.5 equiv), KOtBu (2.5 equiv), c-hexane/THF (1/2, v/v, 0.8 ml), rt, 2 h. †Ni(COD)2 (10 mol%). Isolated yields. c Late-stage defluorosilylation of fluorine-containing pharmaceuticals

Notably, a series of substituted aryl silanes (3m–3w) were successfully prepared using reaction conditions identical to those for π-extended fluoroarenes, despite the different electronic state of the arenes, including high electron-donating NMe2 substitution (3r). These results indicate that a nucleophilic aromatic substitution is highly unlikely to occur in this reaction. The reactivity of simple fluoroarenes was comparable to that of π-extended systems in this ligand-free and mild Ni-catalyzed defluorosilylation, rendering it a highly advantageous protocol for the preparation of aryl silanes. Particularly noteworthy is that fluoropyridine substrates (1×, 1aa) can be transformed under these conditions. Substrates bearing more than one fluorine group (1aa–1cc) were also successfully monosilylated by carefully adjusting the stoichiometry of the reaction.

Prompted by our findings, we speculated that such a defluorosilylation strategy could also be extended to fluoroalkane substrates (sp3 C–F silylation; Fig. 2b). Strikingly, with our system, a wide variety of alkyl fluorides were successfully converted into alkyl silanes in excellent yield, even in the absence of the Ni catalyst. Namely, alkyl fluorides including primary benzylic fluorides (4a–4e), secondary fluorides (4f–4h, 4j), and an alkyl fluoride (4l) were smoothly transformed into the corresponding silylboranes using only KOtBu as the activation agent. Defluorosilylation of fluorenyl fluoride 4i and (1-fluorocyclobutyl)benzene (4k) was achieved using Ni(COD)2 as the catalyst to provide alkyl silanes 5i and 5k, respectively. Remarkably, in the case of 4k with tetra-substituted C–F bonds at the cyclobutyl ring, the silylation position was shifted to the neighboring secondary carbon to provide 5k, presumably due to the steric hindrance. In all the cases, C–H bond silylation products were not detected27.

Synthetic application

In light of these results, the major advantage of this mild and ligand-free C–F activation procedure is its tolerance toward a wide range of functional groups. We envisioned that our silylation protocol could be applied to the late-stage diversification of fluorine-containing bioactive molecules (Fig. 2c). As shown, steroid derivative 7 was synthesized in moderate yield (41%) under the same reaction conditions. Similarly, pitavastatin analogue 8, bearing an electrophilic carbonyl group and an N-heteroaromatic ring, which in some cases may reduce the efficiency of metal catalysts, was converted into 9 in 50% yield. These results clearly demonstrate the potential utility of this defluorosilylation protocol as a platform for the late-stage functionalization of drugs. The silylated products may potentially serve as useful synthetic building blocks for versatile transformations, and some selected synthetic applications of representative silanes obtained in this work are demonstrated (Fig. 3). For instance, triethylarylsilane 3a can be readily coupled with thiophene via a Pd-catalyzed direct C–H arylation to give 11 in excellent yield with high β-selectivity (Fig. 3a)28. Furthermore, 3a smoothly undergoes chlorination, bromination, and iodination to furnish 12–14 in good yield (Fig. 3b). The desilylative acetoxylation of 3a was performed in the presence of Pd(OAc)2 as a catalyst and PhI(OCOCF3) in AcOH (Fig. 3c). This reaction represents a protocol for the phenolation of electron-rich aryl fluorides29. The catalytic carboxylation of the C(sp3)-F bond of 4c was successfully achieved in moderate yield by the sequential reaction, i.e., via a Ni(COD)2-catalyzed defluorosilylation, followed by a C(sp3)-Si bond activation to incorporate CO2 under promotion of a fluoride anion (Fig. 3d)30.

Competition between silylation and borylation

The use of silylboranes for the borylation of aryl, alkenyl, and alkyl halides (Br, I) in the presence of an alkoxy base has been previously reported31. Interestingly, under the applied defluorosilylation conditions, chlorine-, bromine-, and iodine-substituted arenes and alkanes afforded a mixture of silylated and borylated compounds, whereby the borylated compounds were the major products, except for the alkyl chloride, which exhibited good selectivity toward the silylated product (Fig. 4). As has already been shown using fluoro-compounds (Fig. 2), borylation products are not detected using our protocol, while silanes are the main products via C–F bond functionalization. This behavior demonstrates the outstanding advantage of the use of fluorine in our reaction system compared to other halogens. Moreover, competitive experiments suggested that the C–F bond is more inert than the C–Cl, C–Br, and C–I bond in 1-chloro-3-fluorobenzene, 1-bromo-3-fluorobenzene, and 1-fluoro-3-iodobenzene under the conditions applied in this Ni(COD)2-catalyzed defluorosilylation (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Mechanistic investigations

Several experiments were conducted to gain insight into the mechanism of this transformation (Fig. 5a). To discuss the possibility of a radical-mediated reaction pathway, we attempted a radical-clock experiment using 4-(2-fluorophenyl)-1-butene (20) as the substrate. Under standard catalytic conditions, the reaction of 20 with Et3SiBpin afforded defluorosilylated 21 (51%), while cyclization products were not detected (Fig. 5a). This result indicates that free radical species generated by single-electron transfer (SET) processes from the electron-rich Ni(0) center leading to carbon-centered radicals can be excluded32. In addition, we examined the reaction in the presence of radical scavengers, such as 9,10-dihydroanthracene (DHA), toluene, and 1-hexene (Fig. 5a). In all cases, the reactions proceeded smoothly to provide the desired 3a in excellent yield, ruling out the generation of triethylsilyl radicals by either homolysis of the Si–B bond or from a silyl anion via SET33. Overall, these results suggest that the defluorosilylation reaction does not involve free radical intermediates.

Proposed mechanism

On the basis of the experimental results, we propose that the defluorosilylation reaction proceeds as shown in Fig. 5b. First, silylborane 2a reacts with a mole of KOtBu to form intermediate A, which then rearranges into highly nucleophilic, silyl anionic species C via intermediate B34. Complex C undergoes a transmetalation with Ni(COD)2 in the presence of a second mole of KOtBu to generate the active catalyst complex D under concomitant release of stable [BPin(OtBu)2]K. The process from 2a to D, i.e., the first step in Fig. 5b, has been accurately described by Avasare and co-workers based on DFT calculations34. We confirmed this reaction process by the detection of intermediate A by 11B NMR studies (Supplementary Fig. 5). Species D generated in the first step undergoes a second step to furnish 3. The mechanism from D with 1 to 3 has also been simulated based on the report by Avasare and co-workers. D reacts with fluoroarenes 1 to form π-nickel complex E, which may undergo two different pathways, i.e., a and b34,35. In pathway a, the silyl anion performs a nucleophilic attack on the fluorine-substituted carbon of the aryl ring by intramolecular SNAr (I-SNAr), assisted by a transfer of the π-bond density of the aryl ring to the d-orbital of nickel (Fig. 5b, path a)34,36,37. The fluorine atom coordinates to the Ni center, where K+ also assists the C–F bond cleavage to provide G via F. Finally, COD coordinates to the Ni center with the formed KF to provide aryl silanes 3. The generation of KF was confirmed by 19F NMR studies (Supplementary Figs. 6–8).

The ability of internal nucleophilic aromatic substitution (path a) is attributed to the η2 coordination with nickel under retention of the aromaticity, which is more suitable for π-extended aromatic rings. However, simple fluoroarenes, for which the aromatic addition in path a is unfavorable, also successfully engaged in the defluorosilylation (Fig. 2), most likely due to relatively rigid ring and high barrier of aromaticity loss. Alternatively, C–F bond cleavage might occur through a non-classical oxidative pathway via the five-centered transition state H, followed by C–F bond cleavage. The C–F bond activation is assisted by the binding of K+ to F to afford inert KF and the C-Ni intermediate I. The reductive elimination of I is assisted by COD to furnish 3 under concomitant regeneration of Ni(COD)2. 19F NMR experimental studies support the generation of KF (−213 ppm) and show two new peaks (−114 ppm and −135 ppm) for the potential intermediates such as E, F, G, and H during the transformation (Supplementary Fig. 6). The peak at −114 ppm appeared soon, while that for 1a (−117 ppm) disappeared within 20 min. The peak at −114 ppm remained for 60 min and gradually disappeared over 20 h under concomitant emergence of a peak for KF (−213 ppm). Another peak at −135 ppm appeared after 40 min and disappeared after 60 min. Although more studies are necessary to fully interpret these results, transition states/charged intermediates such as η2-arene nickel complexes E, F, G, H, and I may be involved in the activation of the C–F bond.

A conventional cross-coupling mechanism is also possible, in which C–F bond cleavage proceeds via an oxidative addition of aryl fluorides to Ni(0), followed by a transmetalation and a reductive elimination (Supplementary Fig. 9). Generally, the oxidative addition step needs high reaction temperature to overcome the C–F bond-cleavage barrier. However, our results indicate that the defluorosilylation could proceed under milder conditions (room temperature). Furthermore, electron-deficient substrates are normally preferred during the oxidative addition step. However, substrates such as trifluoromethyl- and pentafluorosulfanyl-substituted aryl fluorides did not engage in the defluorosilylation under the optimized reaction conditions (Supplementary Fig. 1). These results demonstrate that the C–F cleavage does not proceed via a conventional oxidative addition.

In the case of alkyl fluorides, the reaction does not depend on the presence of the Ni catalyst. The results indicate that the highly nucleophilic, silyl anionic species C directly reacts with alkyl fluorides 4 to 5 via an SN2 process (Fig. 5b). Especially, the rearrangement of the silyl group in the reaction of 4k is remarkable. To gain insight into the process of this transformation, we have examined the reaction of 4k in the absence/presence of 2a and withtout Ni(COD)2. These reactions afforded only aryl cyclobutene 4k′ via an elimination pathway (Supplementary Fig. 10, eq1). However, 4k could be efficiently converted into 5k in the presence of Ni(COD)2 (Supplementary Fig. 10, eq2), which indicates that 4k′ serves as an intermediate for the defluorosilylation of 4k. Based on this notion, we have developed a hypothetical mechanism (Fig. 5b). Initially, the elimination of the fluorine from the cyclobutyl ring is triggered by KOtBu to give 4k′, followed by coordinating of the silane/Ni(COD)2 base complex D to generate the intermediate η2-arene nickel complex J38,39. Subsequently, J is subject to an addition and reductive elimination to afford the corresponding silane (5k).

Discussion

We have presented an efficient Ni-based catalytic system that is capable of activating the C–F bonds of fluoroarenes in the absence of additional ligands to provide aryl silanes in good to high yield. This protocol for the preparation of aryl silanes is characterized by its mild conditions and wide substrate scope of inert fluoroarenes. The defluorosilylation of alkyl fluorides is directly achieved under very similar conditions, even in the absence of a Ni catalyst. Given the widespread presence of fluorinated compounds in commercially available chemicals, drugs, and functional materials, and the wide range of applications of organosilicon compounds, this strategy should become a powerful tool in organic synthesis, especially for the structural design and potential late-stage functionalization of drug lead compounds.

Methods

General procedure for defluorosilylation of aryl fluorides

To a flame-dried screw-capped test tube were sequentially added a fluoroarene 1 (0.20 mmol, 1 equiv), silylborane 2 (0.30 mmol, 1.5 equiv), Ni(COD)2 (5.5 mg, 0.02 mmol, 10 mol%), KOtBu (56.1 mg, 0.5 mmol, 2.5 equiv) and c-hexane/THF (1/2, v/v, 0.8 ml) in a glovebox filled with argon gas. The tube with the mixture was sealed and removed from the glovebox, and stirred at room temperature for 2–12 h. The reaction progress was monitored by TLC. Then, the mixture was added saturated aqueous ammonium chloride (3 ml) and extracted with EtOAc (3 × 3 ml). The combined organic extract was dried over MgSO4 and filtrated. The filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified to give the silanes.

General procedure for defluorosilylation of alkyl fluorides

To a flame-dried screw-capped test tube were sequentially added a fluoroalkanes 1 (0.20 mmol, 1 equiv), silylborane 2a (0.30 mmol, 1.5 equiv), KOtBu (56.1 mg, 0.5 mmol, 2.5 equiv) and c-hexane/THF (1/2, v/v, 0.8 ml) in a glovebox filled with argon gas. The tube with the mixture was sealed and removed from the glovebox, and stirred at room temperature for 2–12 h. The reaction progress was monitored by TLC. The mixture was then added saturated aqueous ammonium chloride (3 ml) and extracted with EtOAc (3 × 3 ml). The combined organic extract was dried over MgSO4 and filtrated. The filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified to give the silanes.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information. All relevant data are also available from the authors.

References

Wang, J. et al. Fluorine in pharmaceutical industry: fluorine-containing drugs introduced to the market in the last decade (2001-2011). Chem. Rev. 114, 2432–2506 (2014).

Kirsch, P. Modern Fluorooganic Chemistry (Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2004).

Eisenstein, O., Milani, J. & Perutz, R. N. Selectivity of C-H activation and competition between C-H and C-F bond activation at fluorocarbons. Chem. Rev. 117, 8710–8753 (2017).

Ahrens, T., Kohlmann, J., Ahrens, M. & Braun, T. Functionalization of fluorinated molecules by transition-metal-mediated C-F bond activation to access fluorinated building blocks. Chem. Rev. 115, 931–972 (2015).

Amii, H. & Uneyama, K. C-F bond activation in organic synthesis. Chem. Rev. 109, 2119–2183 (2009).

Luo, Y.-R. Comprehensive Handbook of Chemical Bond Energies (CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, 2007).

Tobisu, M., Xu, T., Shimasaki, T. & Chatani, N. Nickel-catalyzed Suzuki–Miyaura reaction of aryl fluorides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 19505–19511 (2011).

Yoshikai, N., Matsuda, H. & Nakamura, E. Hydroxyphosphine ligand for nickel-catalyzed cross-coupling through nickel/magnesium bimetallic cooperation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 9590–9599 (2009).

Ackermann, L., Born, R., Spatz, J. H. & Meyer, D. Efficient aryl-(hetero)aryl coupling by activation of C-Cl and C-F bonds using nickel complexes of air-stable phosphine oxides. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 44, 7216–7219 (2005).

Terao, J., Ikumi, A., Kuniyasu, H. & Kambe, N. Ni- or Cu-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction of alkyl fluorides with Grignard reagents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 5646–5647 (2003).

Guo, W. H., Min, Q. Q., Gu, J. W. & Zhang, X. Rhodium-catalyzed ortho-selective C-F bond borylation of polyfluoroarenes with Bpin-Bpin. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 9075–9078 (2015).

Arisawa, M., Suzuki, T., Ishikawa, T. & Yamaguchi, M. Rhodium-catalyzed substitution reaction of aryl fluorides with disulfides: p-orientation in the polyarylthiolation of polyfluorobenzenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 12214–12215 (2008).

Terrier, F. Modern Nucleophilic Aromatic Substitution (Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2013).

Niwa, T., Ochiai, H., Watanabe, Y. & Hosoya, T. Ni/Cu-catalyzed defluoroborylation of fluoroarenes for diverse C-F bond functionalizations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 14313–14318 (2015).

Liu, X. W., Echavarren, J., Zarate, C. & Martin, R. Ni-catalyzed borylation of aryl fluorides via C-F cleavage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 12470–12473 (2015).

Komiyama, T., Minami, Y. & Hiyama, T. Recent advances in transition-metal-catalyzed synthetic transformations of organosilicon reagents. ACS Catal. 7, 631–651 (2016).

Tanaka, J., Suzuki, S., Tokunaga, E., Haufe, G. & Shibata, N. Asymmetric desymmetrization via metal-free C-F bond activation: synthesis of 3,5-diaryl-5-fluoromethyloxazolidin-2-ones with quaternary carbon centers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 9432–9436 (2016).

Boebel, T. A. & Hartwig, J. F. Iridium-catalyzed preparation of silylboranes by silane borylation and their use in the catalytic borylation of arenes. Organometallics 27, 6013–6019 (2008).

Yue, H. et al. Catalytic ester and amide to amine interconversion: nickel-catalyzed decarbonylative amination of esters and amides by C−O and C−C bond activation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 129, 4346–4349 (2017).

Hie, L. et al. Conversion of amides to esters by the nickel-catalysed activation of amide C-N bonds. Nature 524, 79–83 (2015).

Schaub, T. et al. C−F activation of fluorinated arenes using NHC-stabilized nickel(0) complexes: selectivity and mechanistic investigations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 9304–9317 (2008).

Zarate, C. & Martin, R. A mild Ni/Cu-catalyzed silylation via C–O cleavage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 2236–2239 (2014).

Zhou, J. et al. Preparing (multi)fluoroarenes as building blocks for synthesis: nickel-catalyzed borylation of polyfluoroarenes via C–F bond cleavage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 5250–5253 (2016).

Ouyang, K., Hao, W., Zhang, W. X. & Xi, Z. Transition-metal-catalyzed cleavage of C-N single bonds. Chem. Rev. 115, 12045–12090 (2015).

Tobisu, M. & Chatani, N. Cross-couplings using aryl ethers via C-O bond activation enabled by nickel catalysts. Acc. Chem. Res. 48, 1717–1726 (2015).

Cornella, J., Zarate, C. & Martin, R. Metal-catalyzed activation of ethers via C-O bond cleavage: a new strategy for molecular diversity. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 8081–8097 (2014).

Toutov, A. A. et al. Silylation of C-H bonds in aromatic heterocycles by an earth-abundant metal catalyst. Nature 518, 80–84 (2015).

Funaki, K., Sato, T. & Oi, S. Pd-catalyzed β-selective direct C-H bond arylation of thiophenes with aryltrimethylsilanes. Org. Lett. 14, 6186–6189 (2012).

Gondo, K., Oyamada, J. & Kitamura, T. Palladium-catalyzed desilylative acyloxylation of silicon-carbon bonds on (trimethylsilyl)arenes: synthesis of phenol derivatives from trimethylsilylarenes. Org. Lett. 17, 4778–4781 (2015).

Mita, T., Michigami, K. & Sato, Y. Sequential protocol for C(sp3)–H carboxylation with CO2: transition-metal-catalyzed benzylic C–H silylation and fluoride-mediated carboxylation. Org. Lett. 14, 3462–3465 (2012).

Yamamoto, E., Izumi, K., Horita, Y. & Ito, H. Anomalous reactivity of silylborane: transition-metal-free boryl substitution of aryl, alkenyl, and alkyl halides with silylborane/alkoxy base systems. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 19997–20000 (2012).

Tasker, S. Z., Standley, E. A. & Jamison, T. F. Recent advances in homogeneous nickel catalysis. Nature 509, 299–309 (2014).

Chatgilialoglu, C., Ingold, K. U. & Scaiano, J. C. Absolute rate constants for the addition of triethylsilyl radicals to various unsaturated compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 105, 3292–3296 (1983).

Jain, P., Pal, S. & Avasare, V. Ni(COD)2-catalyzed ipso-silylation of 2-methoxynaphthalene: a density functional theory study. Organometallics 37, 1141–1149 (2018).

Zarate, C., Nakajima, M. & Martin, R. A mild and ligand-free Ni-catalyzed silylation via C-OMe cleavage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 1191–1197 (2017).

O’Reilly, M. E., Johnson, S. I., Nielsen, R. J., Goddard, W. A. & Gunnoe, T. B. Transition-metal-mediated nucleophilic aromatic substitution with acids. Organometallics 35, 2053–2056 (2016).

Cornella, J., Gomez-Bengoa, E. & Martin, R. Combined experimental and theoretical study on the reductive cleavage of inert C-O bonds with silanes: ruling out a classical Ni(0)/Ni(II) catalytic couple and evidence for Ni(I) intermediates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 1997–2009 (2013).

Kanyiva, K. S. et al. Hydrofluoroarylation of alkynes with fluoroarenes. Dalton Trans. 39, 10483–10494 (2010).

Yoshikai, N., Matsuda, H. & Nakamura, E. Ligand exchange as the first irreversible step in the nickel-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction of Grignard reagents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 15258–15259 (2008).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI grants JP 18H02553 (KIBAN B) and JP 18H04401 (Middle Molecular Strategy), as well as the Asahi Glass Foundation. B.C. thanks CSC for CSC Scholarship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.S. conceived the concept. B.C. optimized the reaction conditions and surveyed the substrate scope. S.J. prepared the starting materials. N.S. directed the project. N.S., E.T., and B.C. prepared the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cui, B., Jia, S., Tokunaga, E. et al. Defluorosilylation of fluoroarenes and fluoroalkanes. Nat Commun 9, 4393 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-06830-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-06830-w

This article is cited by

-

Transition-metal-free silylboronate-mediated cross-couplings of organic fluorides with amines

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Opportunities with calcium Grignard reagents and other heavy alkaline-earth organometallics

Nature Reviews Chemistry (2023)

-

Hydrothermal defluorination of fluorobenzene in the presence of sodium hydroxide

Journal of Material Cycles and Waste Management (2023)

-

Regioselective Ni-Catalyzed reductive alkylsilylation of acrylonitrile with unactivated alkyl bromides and chlorosilanes

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Catalyst-free carbosilylation of alkenes using silyl boronates and organic fluorides via selective C-F bond activation

Nature Communications (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.