Abstract

Conversion of naturally abundant nitrogen to ammonia is a key (bio)chemical process to sustain life and represents a major challenge in chemistry and biology. Electrochemical reduction is emerging as a sustainable strategy for artificial nitrogen fixation at ambient conditions by tackling the hydrogen- and energy-intensive operations of the Haber–Bosch process. However, it is severely challenged by nitrogen activation and requires efficient catalysts for the nitrogen reduction reaction. Here we report that a boron carbide nanosheet acts as a metal-free catalyst for high-performance electrochemical nitrogen-to-ammonia fixation at ambient conditions. The catalyst can achieve a high ammonia yield of 26.57 μg h–1 mg–1cat. and a fairly high Faradaic efficiency of 15.95% at –0.75 V versus reversible hydrogen electrode, placing it among the most active aqueous-based nitrogen reduction reaction electrocatalysts. Notably, it also shows high electrochemical stability and excellent selectivity. The catalytic mechanism is assessed using density functional theory calculations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ammonia (NH3) is an essential building block for manufacturing synthetic chemicals, such as fertilizers, medicaments, dyes, explosives, and resins1,2,3. NH3 has also received attention as an alternative energy carrier to advance a low-carbon society due to its large hydrogen capacity (17.6 wt%) and high energy density (4.3 kWh h–1)4. The ever-increasing demand for NH3 has stimulated significant research interest in artificial nitrogen (N2) fixation5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13. Currently, industrial-scale NH3 production mainly relies on the Haber–Bosch process at high temperature and pressure using N2 and hydrogen (H2) as feed gases14,15,16. However, this process accounts for ~2% of the worldwide energy use, i.e., 34 GJ tonNH3–1 and produces a large amount of CO2 (~2 tonCO2 tonNH3–1)17,18. In this regard, it is highly imperative to develop lower-energy N2-fixation methods, ideally operating at low temperature and pressure.

Biological N2 fixation is catalyzed by nitrogenase at ambient conditions through multiple proton and electron transfer steps, requiring a significant energy input delivered by adenosine triphosphate (ATP)11,19,20,21. Encouragingly, electrochemical N2 reduction using protons and electrons can be powered by renewable energy from solar or wind sources, offering a promising environmentally benign process for sustainable artificial N2 fixation at room temperature and pressure22,23. This process, however, is severely challenged by N2 activation and demands efficient catalysts for the N2 reduction reaction (NRR)24,25,26. NRR catalysts based on noble metals (e.g., Au27,28, Ru29, Rh30) show favorable activity, but widespread use is hindered by scarcity and high cost. Much attention has thus focused on designing and developing non-noble-metal alternatives but with low Faradaic efficiency (FE), including Fe2O3-CNT31, Fe3O432, Li+-incorporated PEBCD/C33, MoS234, (110)-oriented Mo nanofilm35, MoO336, Mo2N37, etc. Recently, Lv et al. have reported improved NRR catalytic performance in an amorphous Bi4V2O11-crystalline CeO2 hybrid (BVC-A) with a high FE of 10.16% and a NH3 yield that can reach up to 23.21 μg h–1 mg–1cat. (ref. 38). Compared with the catalysts above, metal-free materials offer an obvious advantage of avoiding metal ion release, thereby reducing the environmental impact. N-doped nanocarbon was recently reported for N2 reduction electrocatalysis with a remarkable NH3 yield of 23.8 μg h–1 mg–1cat., but its FE is only 1.42%39. In this context, the idenfication of new metal-free NRR nanocatalysts that simultaneously achieve high NH3 formation rate and FE is highly desired, which, however, still remains a key challenge.

Boron carbide (B4C), one of the hardest materials in nature next to diamond and cubic boron nitride, possesses high mechanical strength, (electro)chemical stability, and good electronic conductivity, and much attention has focused on its electrochemical uses as electrode material or catalyst substrate for batteries and fuel cells40,41,42,43. Here we report our recent finding that B4C nanosheet behaves as a superb metal-free electrocatalyst toward artificial N2 fixation with excellent selectivity for NH3 formation under ambient conditions. In 0.1 M hydrochloric acid (HCl), it is capable of achieving an average NH3 formation rate and a FE as high as 26.57 μg h–1 mg–1cat. and 15.95% at –0.75 V, respectively, placing it among the most active aqueous-based NRR electrocatalysts. Notably, it also shows high electrochemical stability. In 0.1 M sodium sulfate (Na2SO4), the catalyst still exhibits good activity and selectivity with an NH3 yield of 14.70 μg h–1 mg–1cat. and a FE of 9.24%. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations suggest that the *NH2–*NH2→*NH2–*NH3 reaction is the rate-limiting step.

Results

Synthesis and characterization of boron carbide nanosheet

The B4C nanosheet was produced by liquid exfoliation of bulk B4C (see Methods for preparation details). As shown in Fig. 1a, the X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern for B4C is highly crystalline with diffraction peaks at 19.7°, 22.0°, 23.5°, 31.9°, 34.9°, 37.8°, 53.5°, 63.7°, and 66.7° that are indexed to the (101), (003), (012), (110), (104), (021), (205), (125), and (220) planes of B4C phase (JCPDS No. 35-0798)44, respectively. Further characterization by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) confirm the formation of nanosheets after liquid exfoliation, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1 and Fig. 1b. The higher magnification TEM image (Fig. 1c) reveals the formation of few-layered B4C nanosheet. The high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) image (Fig. 1d) of such a nanosheet shows well-resolved lattice fringes with an interplanar distance of 0.280 nm indexed to the (110) plane of B4C. The corresponding selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern (Fig. 1e) shows well-defined rings indexed to the (012), (110), and (104) planes of B4C. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) spectra of B4C in C 1s (Fig. 1f) and B 1s (Fig. 1g) regions are in good agreement with reported results45. The peaks in B 1s are 187.5 eV and 189.1 eV, which can be associated with the B atoms in B−B and B−C bonds, respectively. The peaks of C 1s spectrum are 284.6 eV (C−C bond), 286.2 eV (C−O bond) and 281.8 eV (C−B bond). The Raman spectroscopy of the B4C presents characteristic Raman peaks at 270, 320, 481, 531, 728, 830, 1000, and 1088 cm–1 assigned to crystalline B4C (Supplementary Fig. 2)46.

Structure, morphology, and composition characterizations. a X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern for B4C. b, c Transmisson electron microscopy (TEM) micrograph (b) and further magnified TEM images (c) for B4C nanosheets. d, e High-resolution TEM image (d) and selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern for one B4C nanosheet (e). Scale bars, b 1 μm; c 300 nm; d 5 nm; e 5 nm−1. f, g X-ray photoelectric spectra of B4C nanosheets in the B 1s (f) and C 1s (g) regions

Electrocatalytic nitrogen reduction performance

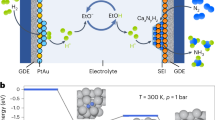

The NRR catalytic performance is examined at controllable applied voltages using a three-electrode system comprising of a graphite rod as a counter electrode, Ag/AgCl as a reference electrode and a B4C nanosheet-loaded carbon paper electrode (CPE) as a working electrode (B4C/CPE; B4C nanosheet loading: 0.1 mg cm−2). During electrolysis, N2 gas is bubbled into the cathode, where protons transported from the electrolyte (0.1 M HCl aqueous solution) can react with N2 on the surface of the catalyst to produce NH3. As shown in Fig. 2a, the current of chrono-amperometry curves at different potentials exert good stability. The current density starts high and then decreases to a steady state, which might be ascribed to double layer charging and a result of decreasing local concentration of H+ and N2 near the electrode surface47.

Electrocatalytic nitrogen reduction performance. a Chrono-amperometry curves at various potentials in N2-saturated 0.1 M HCl. b Ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) absorption spectra of the 0.1 M HCl electrolytes stained with indophenol indicator after electrolysis at a series of potentials for 2 h (7200 s). c NH3 yields and Faradaic efficiencies (FEs) at each given potential in 0.1 M HCl. d Amounts of NH3 generated with a carbon paper electrode (CPE) and a B4C/CPE electrode after 2-h electrolysis at potential of −0.75 V under ambient conditions

To confirm the successful N2 electroreduction in 0.1 M HCl, the production of both NH3 and a possible by-product hydrazine (N2H4) are spectrophotometrically evaluated after 2-h electrolysis operation by the indophenol blue method7 and the method of Watt and Chrisp48, respectively (the corresponding calibration curves are shown in Supplementary Fig. 3–4). Figure 2b shows the UV-Vis absorption spectra of electrolyte colored with indophenol indicator at a series of potentials under N2 bubbling. This detection of NH3 is concrete and unambiguous proof of NH3 formation via the electroreduction of N2 in our B4C/CPE platform at potential ranges from −0.65 V to −1.05 V.

The average NH3 yields and corresponding FEs were determined to exemplify the B4C nanosheet as an efficient catalyst for the fixation of inert N2 molecules into highly valuable NH3 (Fig. 2c). As observed, NH3 yields increase with more negative potential until reaching −0.75 V, where the maximum value of NH3 yield is calculated as 26.57 μg h–1 mg–1cat. with a FE of 15.95%, outperforming most reported aqueous-based NRR catalysts at ambient conditions (Supplementary Table 1). The NH3 yield and FE of NRR increase initially (−0.65 V to −0.75 V) and then start to decrease as the potential is negatively shifted to −1.05 V, which is attributed to the FE of the hydrogen evolution reaction that rises slowly (−0.65 to −0.75 V) and then rises rapidly beyond the cathodic polarization potential of −0.75 V (Supplementary Fig. 5)49. Of note, N2H4 was not detected, indicating this catalyst possesses excellent selectivity for NH3 formation (Supplementary Fig. 6). It is also important to mention that bare CPE has poor electrocatalytic NRR activity (Fig. 2d), revealing that the B4C nanosheet is highly active to catalyze N2 electroreduction.

To verify that the detected NH3 molecules mainly originate from the electrocatalyzed conversion of N2 by B4C/CPE, control experiments were carried out with an Ar-saturated electrolyte as a function of applied potential and with no potential applied to the electrodes under N2 gas (open circuit voltage). The corresponding UV-Vis absorption spectra (Supplementary Fig. 7) and calculated NH3 yields (Fig. 2c) show the presence of a tiny amount of NH3 that may come from sources of contamination (e.g., laboratory, equipment, membrane). A 15N isotopic labeling experiment was also performed to verify the N source of the produced NH3. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 8, the standard samples show a triplet coupling for 14NH4+ and a doublet coupling for 15NH4+ in the 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) spectra, and the use of 14N2 and 15N2 as the feeding gas yields 14NH4+ and 15NH4+, repsectively. These results provide another piece of evidence to strongly support that NH3 was produced by B4C-catalyzed electroreduction of N2.

Stability is also a critical parameter of NRR performance for practical applications. Under sustained N2 gas flow, 30-h electrolysis at a potential of −0.75 V only leads to a slight decrease in current density (Fig. 3a). After long-term electrolysis, the NH3 yield for B4C/CPE shows only 8% decrease compared with the initial one (Supplementary Fig. 9). Furthermore, B4C/CPE presents small changes in NH3 yield and FE during consecutive recycling tests at −0.75 V for 7 times (Fig. 3b), indicating that high electrocatalytic activity for NRR is maintained very well. The TEM image of a B4C nanosheet after long-term electrocatalysis (Supplementary Fig. 10) shows almost no obvious change in morphology. XRD analysis (Supplementary Fig. 11) and XPS spectra (Supplementary Fig. 12) confirm that this catalyst is still B4C in nature after NRR. All these results indicate that this catalyst is robust enough to afford NRR electrocatalysis, which may be attributed to the excellent chemical and electrochemical stability of B4C in acid and its intrinsic high mechanical strength42.

The NRR activity of B4C/CPE was also assessed in neutral media (0.1 M Na2SO4). Production of NH3 and the possible by-product (N2H4) were evaluated by a spectrophotometry method31,48. The calibration curves are shown in Supplementary Fig. 13–14. B4C/CPE still exhibits excellent selectivity without N2H4 production (Supplementary Fig. 15). As shown in Supplementary Fig. 16–17, the NH3 yield can reach the highest value of 14.70 μg h–1 mg–1cat. with a FE of 9.24% at potential of −0.75 V. Time-dependent current density curves of B4C/CPE for NRR at different potentials suggest excellent stability (Supplementary Fig. 18).

Discussion

To identify the active site and atomistic electrocatalytic processes of the NRR on the B4C surface, we used the exchange-correlation functional of Perdew, Burke, and Ernzerhof and the dispersion correction method of Grimme (PBE-D) in the framework of DFT to simulate the corresponding electrocatalytic reactions on the B4C (110) surface using a periodic slab model (see Methods for details). It is well known that the N2 adsorption on the catalyst surface is the first step to initialize the NRR and its initial adsorption configuration plays a vital role for subsequent catalytic reactions. Thus, we have first examined the N2 adsorption on the B4C (110) surface.

There are two main configurations available for the N2 adsorption on the B4C (110) surface. In the end-on configuration, only one terminal N atom is bonded to the B atom on the B4C (110) surface; in the side-on configuration, two terminal N atoms are separately bonded to two vertical B atoms that are located on two adjacent boron clusters (Supplementary Fig. 19). The N2 adsorption potential energies in these two structures are calculated to be 0.65 eV and 0.63 eV at the PBE-D level (free energies: 0.41 eV and 0.34 eV, Supplementary Table 2). Since both configurations have similar energy profiles for the electrochemical N2 fixation reaction on the B4C (110) surface, in the following, we have merely focused on discussing the one starting from the end-on configuration.

Figure 4 shows our DFT computed energy profiles for the electrocatalytic NRR processes on the B4C (110) surface starting from the end-on adsorption structure (optimized structures, Supplementary Fig. 20). The initial adsorption of molecular nitrogen in this end-on configuration releases 0.41 eV free energy. It can be found that the reaction process from the adsorbed *NN to *NH–*NH2 species is completely barrierless and releases 1.70 eV free energy at potential of 0.00 V. The following reaction step, i.e., *NH–*NH2 → *NH2–*NH2, is also facile because of a small energy gap of 0.05 eV (PBE-D level). Different from the situation of other electrocatalyts, the rate-limiting step of the NRR on the B4C (110) surface corresponds to the *NH2–*NH2 → *NH2 + *NH3 reaction, which needs to overcome a barrier of 0.34 eV at potential of 0.00 V (i.e., from −2.06 to −1.72 eV). The final electrocatalytic addition reaction of a proton and electron pair on the adsorbed *NH2 species is barrierless. By contrast, the desorption of the NH3 molecule, i.e. *NH3→NH3, demands 1.73 eV free energy. Nevertheless, such a process remains energetically efficient concerning a lot of accumulated free energy in previous reaction processes (2.70 eV at potential of 0.00 V; see Fig. 4). Further discussion on the limiting potential of the NRR and the associated energy profile (Supplementary Fig. 21) can be found in Supplementary information. Finally, the energy profiles for the electrocatalytic processes starting from the side-on adsorption structure are similar to those from the end-on one (Supplementary Fig. 22).

Density functional theory calculations. Density functional theory (DFT) of Perdew, Burke, and Ernzerhof with the dispersion correction method of Grimme (PBE-D) calculated energy profiles for the electrocatalytic N2 fixation reaction on the B4C (110) surface starting from the end-on adsorption structure (see optimized structures in Supplementary Fig. 20; energy profiles from the side-on adsorption structure in Supplementary Fig. 22). Color code: blue, N; rose, B; gray, C; white, H; the asterisk * denotes an adsorption site

In summary, a B4C nanosheet has been experimentally proven as a superior metal-free electrocatalyst for artificial N2 fixation to NH3 with excellent selectivity at room temperature and ambient pressure. This catalyst achieves a high NH3 yield of 26.57 µg h–1 mg–1cat. and a high FE of 15.95% at a potential of −0.75 V in 0.1 M HCl, with high electrochemical stability. Impressively, B4C/CPE still exhibits good NRR activity in neutral media. Further DFT calculations reveal that the *NH2–*NH2→*NH2–*NH3 reaction is the rate-limiting step. This study not only provides an attractive metal-free electrocatalyst material for NH3 synthesis, but also opens up an exciting new avenue to the rational design of B4C-based nanocatalysts with enhanced performance for N2-fixation applications.

Methods

Sample preparation

Commercial bulk B4C was purchased from Aladdin Ltd. (Shanghai, China). All reagents were analytical reagent grade without further purification. The water used throughout all experiments was purified through a Millipore system. A total of 1 g bulk B4C was dispersed in 10 mL ethanol and stripped by ultrasonic cell disruptor for 1 h. Subsequently, the resulting dispersion was centrifuged for 10 min at 3000 rpm and the supernatant containing B4C nanosheet was decanted gently. Next, 710 µL of the obtained solution was added into 250 µL H2O containing 40 µL of 5 wt% Nafion and sonicated for 1 h to form a homogeneous ink. Then, 50 µL of the dispersion was loaded onto a carbon paper electrode with area of 1 × 1 cm2 and dried under ambient conditions, the catalyst loading mass is 0.1 mg cm–2.

Characterization

XRD pattern was recorded using a LabX XRD-6100 X-ray diffractometer, with a Cu Kα radiation (40 kV, 30 mA) of wavelength 0.154 nm (SHIMADZU, Japan). The structures of the samples were determined by TEM images on a HITACHI H-8100 electron microscopy (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) operated at 200 kV. SEM image was obtained on a Hitachi S-4800 field emission scanning electron microscope at an accelerating voltage of 20 kV. XPS measurements were performed on an ESCALABMK II X-ray photoelectron spectrometer using Mg as the exciting source. The absorbance data of spectrophotometer were measured on SHIMADZU UV-1800 UV-Vis spectrophotometer. A gas chromatograph (SHIMADZU, GC-2014C) equipped with MolSieve 5A column and Ar carrier gas was used for H2 quantifications. Gas-phase product was sampled every 1000 s using a gas-tight syringe (Hamilton). 1H NMR spectra were collected on a superconducting-magnet NMR spectrometer (Bruker AVANCE III HD 500 MHz) and dimethyl sulphoxide was used as an internal to calibrate the chemical shifts in the spectra.

Electrocatalytic nitrogen reduction measurements

The reduction of N2 gas (99.99%) was carried out in a two-compartment cell under ambient condition, which was separated by Nafion 211 membrane. The membrane was protonated by first boiling in ultrapure water for 1 h and treating in H2O2 (5%) aqueous solution at 80 °C for another 1 h, respectively. And then, the membrane was treaded in 0.5 M H2SO4 for 3 h at 80 °C and finally in water for 6 h. The electrochemical experiments were carried out with an electrochemical workstation (CHI 660E). The potentials reported in this work were converted to reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) scale via calibration with the following equation: E (vs. RHE) = E (vs. Ag/AgCl) + 0.256 V and the presented current density was normalized to the geometric surface area. For electrochemical N2 reduction, chrono-amperometry tests were conducted in N2-saturated 0.1 M HCl solution (the HCl electrolyte was purged with N2 for 30 min before the measurement).

Quantification of ammonia

When tested in 0.1 M HCl, the concentration of NH3 produced was spectrophotometrically determined by the indophenol blue method7. Typically, 2 mL HCl electrolyte was taken from the cathodic chamber, and then 2 mL of 1 M NaOH solution containing 5% salicylic acid and 5% sodium citrate was added into this solution. Subsequently, 1 mL of 0.05 M NaClO and 0.2 mL of 1% C5FeN6Na2O·2H2O were add into the above solution. After standing at room temperature for 2 h, the UV-Vis absorption spectrum was measured at a wavelength of 655 nm. The concentration-absorbance curves were calibrated using standard NH3 solution (Supplementary Fig. 3) with a series of concentrations. The fitting curve (y = 1.130x + 0.078, R2 = 0.999) shows good linear relation of absorbance value with NH3 concentration by three times independent calibrations. When tested in 0.1 M Na2SO4, the NH3 concentration was measured by a spectrophotometry method31. In detail, 4 mL of post-tested solution was removed from the cathodic chamber. Then, 50 μL of oxidizing solution (NaClO (ρCl = ~4–4.9) and 0.75 M NaOH), 500 µL of coloring solution (0.4 M C7H5O3Na and 0.32 M NaOH) and 50 µL of catalyst solution (0.1 g Na2[Fe(CN)5NO] 2H2O diluted to 10 mL with deionized water) were added sequentially to the sample solution. After standing at 25 °C for 1 h, the UV-Vis absorption spectra were performed. The concentration of indophenol blue was determined using the absorbance at a wavelength of 655 nm. The concentration-absorbance curve was calibrated using standard NH3 solution with a series of concentrations. The fitting curve (y = 0.753x + 0.026, R2 = 0.999) shows good linear relation of absorbance value with NH3 concentration by three times independent calibrations (Supplementary Fig. 13).

Quantification of hydrazine

The amount of N2H4 present in the electrolyte was estimated by the method of Watt and Chrisp48. A mixed solution of 5.99 g C9H11NO, 30 mL HCl, and 300 mL ethanol was used as a color reagent. Calibration curve was plotted as follow: first, preparing a series of standard solutions; second, adding 5 mL above prepared color reagent and stirring 20 min at room temperature; finally, the absorbance of the resulting solution was measured at 455 nm, and the yields of N2H4 were estimated from a standard curve using 5 mL residual electrolyte and 5 mL color reagent. Absolute calibration of this method was achieved using N2H4 solutions of known concentration as standards, and the fitting curve shows good linear relation of absorbance with N2H4 concentration in 0.1 M HCl (Supplementary Fig. 4, y = 0.545x + 0.031, R2 = 0.999) and 0.1 M N2SO4 (Supplementary Fig. 14, y = 1.199x + 0.051, R2 = 0.999) by three times independent calibrations.

Calculation of the Faradaic efficiency and yield

The FE for N2 reduction was defined as the amount of electric charge used for synthesizing NH3 divided the total charge passed through the electrodes during the electrolysis. The total amount of NH3 produced was measured using colorimetric methods. Assuming three electrons were needed to produce one NH3 molecule, the FE could be calculated as follows:

The rate of NH3 formation \(({v_{{\mathrm{NH}}_3}})\) was calculated using the following equation:

where F is the Faraday constant, \({\rm C}_{{\rm NH}_3}\) is the measured NH3 concentration, V is the volume of the HCl electrolyte for NH3 collection, t is the reduction time and mcat. is the catalyst loading mass.

FE for H2 was calculated according to following equation:

where F is the Faraday constant; n is the actually produced H2 (mol), and Q is the quantity of applied electricity.

Calculation details

All DFT calculations are performed using the DMol3 module implemented in the Material Studio 8.0 package50,51. The generalized gradient approximation (GGA) with the PBE exchange-correlation functional is employed52. The empirical dispersion correction proposed by Grimme is used to consider weak van der Waals interaction53. The build-in double numerical plus polarization (DNP) basis set is used to expand the electronic wavefunction. A Monkhorst-Pack k-point grids of 2 × 1 × 1 are used (see Supplementary Table 3 for benchmark). Self-consistent field (SCF) calculations are performed with a convergence criterion of 10−6 au on the total energy and electronic computations. Since the bulk water layer only slightly stabilizes the NRR intermediates54, we have therefore adopted the conductor-like screening model (COSMO) to simulate solvent effects55.

A three-layer 1 × 2 periodic slab model is used to represent the B4C (110) surface that is observed in our HRTEM image (see Supplementary Table 4 for benchmark). A 15 Å vacuum layer is used between the two neighboring slabs to avoid artificial interaction. In geometric optimizations, all atoms except those in the bottom layer are fully relaxed. The adsorption energy (Eads) of species on the B4C (110) surface is defined as:

where Eslab and Emol are the energies of the isolated slab and species, respectively; and Eslab/mol is the energy of the species-adsorbed slab system. The NRR process includes six net coupled proton and electron transfer (CPET) steps (N2 + 6H+ + 6e− → 2NH3). Based on previous theoretical studies54, gaseous hydrogen is used as the source of protons to simulate the reaction at the anode, i.e., H2 ↔ 2H+ + 2e−. Each CPET step includes the transfer of a proton coupled with an electron from solution to an adsorbed species on the B4C (110) surface. For each fundamental step, the Gibbs free energy change (ΔG) is calculated based on the standard hydrogen electrode (SHE) model proposed by Nørskov et al.56,57,58 in which the chemical potential of a proton-coupled-electron pair i.e., µ(H+) + µ(e−) is equal to half of the chemical potential of gaseous hydrogen i.e., 1/2 µ(H2) at a potential of 0 V. Accordingly, the ΔG value can be obtained as follows:

where ΔE is the electronic energy difference, ΔZPE is the change in zero-point energies, T is the temperature (T = 298.15 K), and ΔS is the change of entropy. ΔGU is the free energy contribution connected to electrode potential U. ΔGpH is the H+ free energy correction by the concentration. It is calculated through ΔGpH = 2.303 × kBT × pH where kB is the Boltzmann constant and the value of pH is assumed to be zero in this work. It can be found that the free energy change of each elementary step is increased as the pH value increases. The zero-point energies and entropies of the NRR species are determined from the vibrational frequencies in which only the adsorbed species’ vibrational modes are computed explicitly and the B4C (110) surface is fixed. The entropies and vibrational frequencies of molecules in the gas phase are taken from the NIST database. [http://cccbdb.nist.gov/]

Data availability

The data described in this paper are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

References

Smil, V. Detonator of the population explosion. Nature 400, 415 (1999).

Schlögl, R. Catalytic synthesis of ammonia—a “never-ending story”? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 42, 2004–2008 (2003).

Rosca, V., Duca, M., DeGroot, M. T. & Koper, M. T. M. Nitrogen cycle electrocatalysis. Chem. Rev. 109, 2209–2244 (2009).

Vegge, T. et al. Indirect hydrogen storage in metal ammines. In: Solid State Hydrogen Storage: Materials and Chemistry (British Welding Research Association, Cambridge, UK, 2008).

MacKay, B. A. & Fryzuk, M. D. Dinitrogen coordination chemistry: on the biomimetic borderlands. Chem. Rev. 104, 385–401 (2004).

Kitano, M. et al. Ammonia synthesis using a stable electride as an electron donor and reversible hydrogen store. Nat. Chem. 4, 934–940 (2012).

Zhu, D., Zhang, L., Ruther, R. E. & Hamers, R. J. Photo-illuminated diamond as a solid-state source of solvated electrons in water for nitrogen reduction. Nat. Mater. 12, 836–841 (2013).

Shima, T. et al. Dinitrogen cleavage and hydrogenation by a trinuclear titanium polyhydride complex. Science 340, 1549–1552 (2013).

MacLeod, K. C. & Holland, P. L. Recent developments in the homogeneous reduction of dinitrogen by molybdenum and iron. Nat. Chem. 5, 559–565 (2013).

Čorić, I., Mercado, B. Q., Bill, E., Vinyard, D. J. & Holland, P. L. Binding of dinitrogen to an iron-sulfur-carbon site. Nature 256, 96–99 (2015).

Brown, K. A. et al. Light-driven dinitrogen reduction catalyzed by a CdS: nitrogenase MoFe protein biohybrid. Science 352, 448–450 (2016).

Eizawa, A. et al. Remarkable catalytic activity of dinitrogen-bridged dimolybdenum complexes bearing NHC-based PCP-pincer ligands toward nitrogen fixation. Nat. Commun. 8, 14874 (2017).

Légaré, M.-A. et al. Nitrogen fixation andreduction at boron. Science 359, 896–900 (2018).

Smil, V. Global population and the nitrogen cycle. Sci. Am. 277, 76–81 (1997).

Jennings, J. R. Catalytic ammonia synthesis: fundamentals and practice. (Plenum Press, New York, 1991).

Aika, K. et al. Ammonia, catalysis and manufacture. (Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, New York, Dordrecht, 1995).

Leigh, G. J. Haber–bosch and other industrial processes. In: Catalysts for Nitrogen Fixation. (Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2004).

Nørskov, J., Chen, J., Miranda, R., Fitzsimmons, T. & Stack, R. Sustainable ammonia synthesis, DOE roundtable report. (U.S. department of energy Office of Science, Washington, DC, 2016).

Tanaka, H., Nishibayashi, Y. & Yoshizawa, K. Interplay between theory and experiment for ammonia synthesis catalyzed by transition metal complexes. Acc. Chem. Res. 49, 987–995 (2016).

Chan, M. K., Kim, J. & Rees, D. The nitrogenase FeMo-cofactor and P-cluster pair: 2.2 Å resolution structures. Science 260, 792–794 (1993).

Burgess, B. K. & Lowe, D. J. Mechanism of molybdenum nitrogenase. Chem. Rev. 96, 2983–3012 (1996).

Shipman, M. A. & Symes, M. D. Recent progress towards the electrosynthesis of ammonia from sustainable resources. Catal. Today 286, 57–68 (2017).

Kyriakou, V., Garagounis, I., Vasileiou, E., Vourros, A. & Stoukides, M. Progress in the electrochemical synthesis of ammonia. Catal. Today 286, 2–13 (2017).

van der Ham, C. J. M., Koper, M. T. M. & Hetterscheid, D. G. H. Challenges in reduction of dinitrogen by proton and electron transfer. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 5183–5191 (2014).

Seh, Z. W. et al. Combining theory and experiment in electrocatalysis: insights into materials design. Science 355, eaad4998 (2017).

Guo, C., Ran, J., Vasileff, A. & Qiao, S.-Z. Rational design of electrocatalysts and photo(electro)catalysts for nitrogen reduction to ammonia (NH3) under ambient conditions. Energy Environ. Sci. 11, 45–56 (2018).

Shi, M. M. et al. Au sub-nanoclusters on TiO2 toward highly efficient and selective electrocatalyst for N2 conversion to NH3 at ambient conditions. Adv. Mater. 29, 1606550 (2017).

Bao, D. et al. Electrochemical reduction of N2 under ambient conditions for artificial N2 fixation and renewable energy storage using N2/NH3 cycle. Adv. Mater. 29, 1604799 (2017).

Kugler, K., Luhn, M., Schramm, J. A., Rahimi, K. & Wessling, M. Galvanic deposition of Rh and Ru on randomly structured Ti felts for the electrochemical NH3 synthesis. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17, 3768–3782 (2015).

Liu, H.-m. et al. Surfactant-free atomically ultrathin rhodium nanosheets nanoassemblies for efficient nitrogen electroreduction. J. Mater. Chem. A 6, 3211–3217 (2018).

Chen, S. et al. Electrocatalytic synthesis of ammonia at room temperature and atmospheric pressure from water and nitrogen on a carbon-nanotube-based electrocatalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 2699–2703 (2017).

Liu, Q. et al. Ambient N2 fixation to NH3 electrocatalyzed by spinel Fe3O4 nanorod. Nanoscale, 10, 14386–14389 (2018).

Chen, G.-F. et al. Ammonia electrosynthesis with high selectivity under ambient conditions via a Li+ incorporation strategy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 9771–9774 (2017).

Zhang, L. et al. Electrochemical ammonia synthesis via nitrogen reduction reaction on MoS2 catalyst: theoretical and experimental studies. Adv. Mater. 30, 1800191 (2018).

Yang, D., Chen, T. & Wang, Z. Electrochemical reduction of aqueous nitrogen (N2) at a low overpotential on (110)-oriented Mo nanofilm. J. Mater. Chem. A 5, 18967–18971 (2017).

Han, J. et al. MoO3 nanosheets for efficient electrocatalytic N2 fixation to NH3. J. Mater. Chem. A 6, 12974–12977 (2018).

Ren, X. et al. Electrochemical N2 fixation to NH3 under ambient conditions: Mo2N nanorod as a highly efficient and selective catalyst. Chem. Commun. 54, 8474–8477 (2018).

Lv, C. et al. An amorphous noble-metal-free electrocatalyst enables N2 fixation under ambient conditions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 6073–6076 (2018).

Liu, Y. et al. Facile ammonia synthesis from electrocatalytic N2 reduction under ambient conditions on N-doped porous carbon. ACS Catal. 8, 1186–1191 (2018).

Minakshi, M. & Blackford, M. G. Electrochemical characteristics of B4C or BN added MnO2 cathode material for alkaline batteries. Mater. Chem. Phys. 123, 700–705 (2010).

Lv, H., Peng, T., Wu, P., Pan, M. & Mu, S. Nano-boron carbide supported platinum catalysts with much enhanced methanol oxidation activity and CO tolerance. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 9155–9160 (2012).

Mu, S. et al. Nano-size boron carbide intercalated graphene as high performance catalyst supports and electrodes for PEM fuel cells. Carbon 103, 449–456 (2016).

Song, S. et al. B4C as a stable non-carbon-based oxygen electrode material for lithiumoxygen batteries. Nano Energy 33, 195–204 (2017).

Kou, Z., Guo, B., He, D., Zhang, J. & Mu, S. Transforming two-dimensional boron carbide into boron and chlorine dual-doped carbon nanotubes by chlorination for efficient oxygen reduction. ACS Energy Lett. 3, 184–190 (2017).

Vineesh, T. V. et al. Bifunctional electrocatalytic activity of boron-doped graphene derived from boron carbide. Adv. Energy Mater. 5, 1500658 (2015).

Reddy, K. M., Liu, P., Hirata, A., Fujita, T. & Chen, M. W. Atomic structure of amorphous shear bands in boron carbide. Nat. Commun. 4, 2483 (2013).

Zhou, F. et al. Electro-synthesis of ammonia from nitrogen at ambient temperature and pressure in ionic liquids. Energy Environ. Sci. 10, 2516–2520 (2017).

Watt, G. W. & Chrisp, J. D. Spectrophotometric method for determination of hydrazine. Anal. Chem. 24, 2006–2008 (1952).

Oshikiri, T., Ueno, K. & Misawa, H. Selective dinitrogen conversion to ammonia using water and visible light through plasmon-induced charge separation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 3942–3946 (2016).

Delley, B. An all-electron numerical method for solving the local density functional for polyatomic molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 92, 508–517 (1990).

Delley, B. From molecules to solids with the DMol3 approach. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 7756–7764 (2000).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Grimme, S. Semiempirical GGA-type density functional constructed with a long-range dispersion correction. J. Comput. Chem. 27, 1787–1799 (2006).

Skúlason, E. et al. A theoretical evaluation of possible transition metal electro-catalysts for N2 reduction. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 14, 1235–1245 (2012).

Klamt, A. & Schüürmann, G. COSMO: a new approach to dielectric screening in solvents with explicit expressions for the screening energy and its gradient. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 0, 799–805 (1993).

Nørskov, J. K., Rossmeisl, J., Logadottir, A. & Lindqvist, L. Origin of the overpotential for oxygen reduction at a fuel-cell cathode. J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 17886–17892 (2004).

Rossmeisl, J., Logadottir, A. & Nørskov, J. K. Electrolysis of water on (oxidized) metal surfaces. Chem. Phys. 319, 178–184 (2005).

Peterson, A. A., Abild-Pedersen, F., Studt, F., Rossmeisl, J. & Nørskov, J. K. How copper catalyzes the electroreduction of carbon dioxide into hydrocarbon fuels. Energy Environ. Sci. 3, 1311–1315 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 21575137 and 21522302). We also appreciate Hui Wang from the Analytical and Testing Center of Sichuan University for her help with SEM characterization.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.S. developed the ideas and designed the experiments. X.S., G.C. and B.T. wrote the paper. W.Q., X.R. and X.J. carried out all experiments. X.X., W.F. and G.C. performed all computations. All authors discussed and analysed the data.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qiu, W., Xie, XY., Qiu, J. et al. High-performance artificial nitrogen fixation at ambient conditions using a metal-free electrocatalyst. Nat Commun 9, 3485 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-05758-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-05758-5

This article is cited by

-

Novel metal-free holey BC4N nanostructure for enhanced photoelectrocatalytic nitrogen reduction: insight from grand-canonical density functional theory

Science China Materials (2024)

-

Computational study of transition metal single-atom catalysts supported on nitrogenated carbon nanotubes for electrocatalytic nitrogen reduction

Nano Research (2023)

-

Boosting the interlayer-confined nitrate reduction reaction by in situ electrochemical potassium ion intercalation

Science China Materials (2023)

-

Rational Design of Atomic Site Catalysts for Electrocatalytic Nitrogen Reduction Reaction: One Step Closer to Optimum Activity and Selectivity

Electrochemical Energy Reviews (2022)

-

Two-dimensional Fe-TPPHZ nanosheets for electrohydrogenation of N2 to NH3 under ambient conditions

Journal of Applied Electrochemistry (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.