Abstract

Amines are fundamental motifs in bioactive natural products and pharmaceuticals. Using simple toluene derivatives, a one-pot aminobenzylation of aldehydes is introduced that provides rapid access to amines. Simply combining benzaldehydes, toluenes, NaN(SiMe3)2, and additive Cs(O2CCF3) (0.35 equiv.) generates a diverse array of 1,2-diarylethylamine derivatives (36 examples, 56–98% yield). Furthermore, suitably functionalized 1,2-diarylethylamines were transformed into 2-aryl-substituted indoline derivatives via Buchwald–Hartwig amination. It is proposed that the successful deprotonation of toluene by MN(SiMe3)2 is facilitated by cation–π interactions between the arene and the group(I) cation that acidify the benzylic C–Hs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

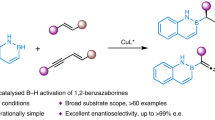

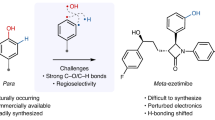

Toluene and xylenes are large volume, inexpensive commodity chemicals commonly used as solvents on industrial scale. As such, there are no better feedstocks for the preparation of more elaborate, high-value organic molecules with applications in pharmaceutical sciences, agrochemicals, and materials chemistry1,2,3. To fully exploit these feedstocks, efficient and economical methods for the selective functionalization of the benzylic C–Hs are required. Recent advances along these lines have been considerable, although many rely on highly reactive stoichiometric oxidants3 or directing groups to facilitate these transformations4,5. Related to this strategy, Stahl6 and Liu7 have recently developed mild methods to generate diarylmethanes via copper-catalyzed arylations of toluene and its derivatives with arylboronic acids (Fig. 1). Palladium-promoted toluene functionalization strategies also hold promise8,9.

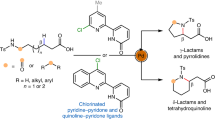

We have been interested in the functionalization of very weakly acidic (pKa up to ~34) benzylic C–Hs of arenes and heteroarenes via deprotonative cross-coupling processes (DCCP). Substrates for DCCP include allyl benzenes (Fig. 2a)10, diarylmethanes11,12,13,14, triarylmethanes15, and benzylic sulfoxides16,17 among others. The success of DCCP relies partly on reversible deprotonation of the benzylic C–Hs of the pronucleophile. For unactivated toluene derivatives, however, we conjectured that the high pKa values (≈43 in DMSO18) of the benzylic C–Hs were far beyond the reach of MN(SiMe3)2 bases [M = alkali metal, pKa ≈ 26 for HN(SiMe3)2 in THF19]. Thus, to address this long-standing challenge, we20,21 and others22 activated the arenes with stoichiometric transition metals by forming (η6-toluene)Cr(CO)3 complexes. The benzylic C–Hs of (η6-toluene)Cr(CO)3 exhibit increased acidity and are reversibly deprotonated with LiN(SiMe3)2, enabling functionalization (Fig. 2b). The group of Matsuzaka improved upon this approach with a ruthenium-sulfonamide-based catalyst (Fig. 2c) for in situ deprotonation of toluene and dehydrative condensation with aromatic aldehydes to generate (E)-stilbenes23.

Benzylic deprotonation and related chemistry. a Arylation of allyl benzene. b Arylation of transition metal-activated toluene derivatives, c catalytic arene activation with a ruthenium complex. d Catalytic deprotonation of allyl benzene and imine addition. e Catalytic 1,4-addition reaction with alkylazaarenes by Kobayshi and co-workers. f Catalytic addition of benzylic C–Hs to styrenes by Guan and co-workers. g Related chemistry with more acidic 2-methyl pyridine. h Traditional approach from Hart and co-workers. i Aminobenzylation of aldehydes (this work). j 1,2-Diphenylethylamine-based drugs and natural products

As a valuable complement, Schneider developed a method for functionalization of allyl benzene (pKa ≈ 3424) catalyzed by NaN(SiMe3)2 (Fig. 2d)25. Benzylic functionalization of more acidic alkylazaarenes (pKa ≈ 35 for 4-methyl pyridine18) catalyzed by KN(SiMe3)2 with N,N-dimethylcinnamamide by Kobayashi and co-workers also represents an advance (Fig. 2e)26,27. More recently, Guan reported a KN(SiMe3)2-catalyzed C–H bond addition of alkylpyridines to simple styrenes (Fig. 2f)28. During the revision process, Brønsted base-catalyzed benzylic C–H bond functionalizations of toluenes and diarylmethanes were reported by Kobayashi29 and Guan30, respectively. Important early contributions involved additions of 2-methyl pyridine (Fig. 2g), and Grignard reagents (Fig. 2h) to in situ generated N-(trimethylsilyl)imines were developed by Giles31 and Hart32,33, respectively.

The results in Fig. 2b–h, as well as our recent work on the use of cation–π interactions to direct C–H functionalization reactions11, inspired us to wonder if cation–π interactions between toluene and earth-abundant alkali metals derived from MN(SiMe3)2 (M = Li, Na, K, Cs) would increase the acidity of the benzylic C–Hs sufficiently to allow reversible deprotonation under relatively mild conditions. If indeed such an equilibrium could be established, which would undoubtedly lie very far to the side of toluene, would it be possible to trap the fleeting benzyl organometallic with an electrophile before rapid quenching with the conjugate acid of the base [HN(SiMe3)2]? Finally, if benzylic organometallic species could be generated from toluene and its derivatives, would it be possible to transform them into high-value added building blocks of interest to the pharmaceutical industry?

Herein, we report a successful tandem C–C and C–N bond-forming reaction for the one-pot chemoselective aminobenzylation of aldehydes with toluene derivatives (Fig. 2i). This method enables rapid access to a variety of 1,2-diphenylethylamine derivatives that are important building blocks in natural products and potent drugs and pharmaceuticals (NEDPA, NPDPA, lefetamine, ephenidine, MT-45, and PAO1, Fig. 2j)34,35,36.

Results

Preliminary reaction optimization

Initial screens were conducted with benzaldehyde (1a) in toluene (2a) with three different bases [LiN(SiMe3)2, NaN(SiMe3)2, and KN(SiMe3)2] at 110 °C for 12 h (Table 1, entries 1–3, AY = assay yield, determined by 1H NMR of unpurified reaction mixtures). LiN(SiMe3)2 failed to give the desired product 3aa (entry 1), although it is known to react with benzaldehyde to generate aldimine37,38. This screen led to the identification of NaN(SiMe3)2 as a promising base, affording the product 3aa in 47% assay yield (entry 2). It is known that K+ forms the stronger cation–π interactions in solution in the series Li+, Na+, and K+39,40; however, under our conditions the potassium amide was not as successful as NaN(SiMe3)2 (entry 3 vs. 2). This may be because KN(SiMe3)2 is less efficient in the formation of the aldimine37. We were also interested in examining the use of CsN(SiMe3)2. Unfortunately, this base is not widely available commercially like its lighter analogs41. It can be prepared, of course, but this would make the methods that require its use less attractive. O’Hara and co-workers found that CsN(SiMe3)2 could be generated by mixing NaN(SiMe3)2 with CsX (X = Cl, Br, or I)40. Furthermore, combining CsN(SiMe3)2 with equimolar NaN(SiMe3)2 led to formation of a sodium–cesium amide polymer [toluene•CsNa(N(SiMe3)2)2]∞39. It is noteworthy that the toluene in this structure forms a cation–π complex with the Cs+ [Cs•••toluene(centroid) = 3.339 Å]. Such cation–π interactions are often found in the structures of organometallic complexes42,43,44.

On the basis of the structures in these reports, we examined a variety of cesium salts with commercially available NaN(SiMe3)2 in 1:1 ratio (entries 4–13). This screen led to the identification of NaN(SiMe3)2 and CsTFA (TFA = trifluoroacetate) as the best combination, generating 3aa in 92% AY (entry 13). Other cesium salts either did not promote the transformation (CsF, Cs2CO3, CsCl, CsOAc, entries 4–7) or gave low yields of 3aa (Cs2SO4, CsClO4, EtCOOCs, CsBr, CsI, entries 8–12). Upon decreasing the amounts of both base and CsTFA [2 equiv. NaN(SiMe3)2 and 0.35 equiv. CsTFA], the AY of 3aa remained high (95%, entry 15). Further lowering the CsTFA to 0.2 equiv, however, led to a slight decrease in assay yield (89%, entry 16). The reactivity decreased significantly when catalytic MN(SiMe3)2 was used (41%, entry 17, 20 mol %). We wanted to determine if the combination of MN(SiMe3)2 (M = Li, K) and CsTFA could affect the reactivity under the conditions of entry 15, so we reexamined LiN(SiMe3)2 and KN(SiMe3)2 with CsTFA (35 mol%). In the presence of CsTFA, the difference between LiN(SiMe3)2 and NaN(SiMe3)2 was negligible (entry 15 vs 18). KN(SiMe3)2, however, still gave low assay yield (entry 19). We also examined the impact of temperature on the reactivity under the conditions of entry 15. As the temperature was decreased from 110 to 30 °C, the reactivity decreased slightly at 80 and 40 °C (entries 20 and 21). The reactivity decreased dramatically at 30 °C affording the desired product in 67% yield (entry 22). At this point, the nature of the active base and even the amount of Cs in solution remain the subject of future work. Our optimized reaction conditions for the one-pot aminobenzylation of benzaldehyde are 2 equiv. of NaN(SiMe3)2, 1 mL toluene, and 35 mol% CsTFA at 110 °C for 12 h.

Scope of aldehydes

With the optimized reaction conditions in hand, we next examined the scope of aldehydes in the aminobenzylation with toluene (Table 2). In addition to the parent benzaldehyde (1a), a variety of aryl and heteroaryl aldehydes were successfully employed. Benzaldehydes bearing electron-donating groups, such as 4-t-Bu, 4-methyl, 4-methoxy, and 4-N,N-dimethylamino, exhibited very good reactivity, producing 3ba–3ea in 70–88% yield. Benzaldehydes possessing halogens are also good coupling partners even at 40 °C. 4-Fluoro-, 4-chloro-, and 4-bromobenzaldehydes afforded the corresponding products in 90%, 98%, and 83% yield, respectively (3fa–3ha). Likewise, 2-bromo (3ia, 95%) and 2-chloro (3ja, 98%) benzaldehydes were very good substrates. Of course, these products could potentially be further functionalized through cross-coupling reactions. Substrates with extended π-systems, such as 1- and 2-naphthyl aldehydes, furnished products in 92–94% yield (3ka and 3la).

In general, benzaldehyde derivatives bearing additional functional groups and heteroatoms were well tolerated. Nitriles are known to undergo nucleophilic additions with organometallic reagents45. Under our aminobenzylation conditions, however, 4-cyano benzaldehyde afforded the desired product (3ma) in 70% yield with high chemoselectivity. Considering that, fluorinated compounds are extremely important in medicinal chemistry46, we examined fluorinated benzaldehydes. Both 4-trifluoromethyl- and 4-trifluoromethoxy benzaldehydes were excellent substrates, affording 3na and 3oa in 97% and 90% yield, respectively. Benzaldehydes containing 4-SMe, 4-Ph, and 4-OPh groups rendered the products in 88–93% yield (3pa–3ra). The silyl-ether containing product (3sa, 77%) could be accessed via this protocol. Heterocyclic amines exhibit various bioactivities47. Amines containing indole, pyridine, pyrrole, and quinoline groups could be prepared with our approach, as exemplified by the generation of 3ta–3xa in 66–97% yield. Cinnamaldehyde was a competent partner under our conditions, as exemplified by the synthesis of allylic amine 3ya in 56% yield.

Scope of toluene derivatives

Next, the substrate scope of toluene derivatives was examined in the aminobenzylation of benzaldehyde (1a) (Table 3). Toluenes bearing electron-donating groups, such as 4-iPr (2b), 4-OMe (2c), and 2-OMe (2d), provided the corresponding products in 78%, 66%, and 77% yield, respectively. It is noteworthy that the methyl of p-cymene (2b) undergoes reaction with high chemoselectivity. 4-Chlorotoluene (2e) exhibited reduced reactivity, furnishing 3ae in 66% yield at 40 °C. In contrast, 2-chloro- and 2-bromotoluenes exhibited good reactivity, giving the desired products (3af and 3ag) in 86% and 85% yield, respectively. For polymethyl-substituted toluenes (2h–2k), excellent chemoselectivity was observed, affording the products (3ah–3ak) in 81–96% yield. It is noteworthy that mesitylene was an outstanding substrate (96% yield, 3ak). π-Extended 1-methylnaphthalene was also a good substrate, affording 3al in 88% yield.

Reaction pathway

Based on the results above, we propose a reaction pathway for this one-pot aminobenzylation process. First, the NaN(SiMe3)2 reacts with the aldehyde to form the intermediate adduct A48, followed by an aza-Peterson olefination to afford the N-(trimethylsilyl)imine B, which was not isolated but reacted directly in this one-pot process. In the presence of NaN(SiMe3)2 and CsTFA, the toluene derivative was reversibly deprotonated to generate an η1- or η3-bound metal complex C and C′49. The deprotonated toluene derivative then attacks the in-situ-generated aldimine B to give the aminobenzylated product 3 after workup (Fig. 3).

Further transformations

For a method to be useful, it must be scalable. To test the scalability of the aminobenzylation, 5 mmol of benzaldehyde (0.53 g) was reacted with 2-bromotoluene (2g) (Fig. 4a). An 81% yield of 3ag was obtained. Additionally, a column-free process for direct synthesis of hydrochloride salt of 3aa was explored. Under the optimized conditions, the salt 3′aa was obtained in 78% yield (Fig. 4b). To further demonstrate the synthetic potential of the aminobenzylation, the product derived from 2-bromotoluene, NaN(SiMe3)2, and benzaldehydes 1a, 1n, 1q, and 1v were readily converted into valuable 2-aryl-substituted indoline derivatives using a Buchwald–Hartwig amination in 81–90% yield (Fig. 4c)50. N-Substituted 2-arylindoline derivatives are used to treat estrogen-deficiency diseases51. Furthermore, the parent 1,2-diphenylethylamine was easily converted to a diverse array of biologically active compounds (Fig. 4d)52.

Discussion

We have advanced a general method for the activation and functionalization of inexpensive toluene feedstocks at the benzylic position via a one-pot aminobenzylation of aldehydes. The reaction takes place without added transition metal catalysts and does not employ preformed main group organometallic reagents. By employing readily available benzaldehydes, commodity toluene derivatives, NaN(SiMe3)2, and substoichiometric Cs(TFA) a diverse array of valuable and biologically active 1,2-diarylethylamine derivatives were conveniently synthesized. The N-alkylated analogs of our diarylethylamines are used as opioid analgesics. Additionally, this one-pot aminobenzylation exhibits remarkable chemoselectivity and excellent functional group tolerance. Suitably substituted aldehyde aminobenzylation products were readily transformed into pharmaceutically relevant 2-aryl-substituted indoline derivatives via Buchwald–Hartwig amination.

We ascribe the success of our aminobenzylation of aldehydes to cation–π interactions between the π-electrons of the toluene derivative and Na+ and/or Cs+ centers. We hypothesize that this interaction acidifies the benzylic C–H bonds, facilitating deprotonation by moderate bases, MN(SiMe3)253,54,55,56,57. Because of its simplicity and potential to produce valuable bioactive building blocks in a single step, we anticipate that this aminobenzylation reaction will find applications in medicinal chemistry.

Methods

General procedure A

To an oven-dried microwave vial equipped with a stir bar under argon atmosphere inside a glove box was added NaN(SiMe3)2 (73.2 mg, 0.40 mmol), cesium trifluoroacetate (CsTFA) (17.2 mg, 0.07 mmol), and toluene (2 mL). Then, the corresponding aldehyde (0.20 mmol) was added via syringe. The microwave vial was sealed with a cap and removed from the glove box. The reaction mixture was heated to 110 °C in an oil bath and stirred for 12 h. The sealed vial was cooled to room temperature, opened to air, and then five drops of water were added. The reaction mixture was passed through a short pad of silica, washed with an additional 6 mL of ethyl acetate (3 × 2 mL), and the combined solutions were concentrated in vacuo. The crude material was loaded onto a column of silica gel for purification of the amine.

General procedure B

To an oven-dried microwave vial equipped with a stir bar under an argon atmosphere inside a glove box was added NaN(SiMe3)2 (73.2 mg, 0.40 mmol), CsTFA (17.2 mg, 0.07 mmol), the toluene derivative (1 mL), and cyclohexane (1 mL). Then, the corresponding aldehyde (0.20 mmol) was added via syringe. The microwave vial was sealed with a cap and removed from the glove box. The reaction mixture was heated to 110 °C in an oil bath and stirred for 12 h. The sealed vial was cooled to room temperature, opened to air, and then five drops of water were added. The reaction mixture was passed through a short pad of silica, washed with additional 6 mL of ethyl acetate (3 × 2 mL), and the combined solutions were concentrated in vacuo. The crude material was loaded onto a column of silica gel for purification of the amine.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files.

Change history

06 September 2018

This Article was originally published without the accompanying Peer Review File. This file is now available in the HTML version of the Article; the PDF was correct from the time of publication.

References

Bai, H. et al. Large-scale synthesis of ultrathin tungsten oxide nanowire networks: an efficient catalyst for aerobic oxidation of toluene to benzaldehyde under visible light. Nanoscale 8, 13545–13551 (2016).

Nandiwale, K. Y., Thakur, P. & Bokade, V. V. Environmentally benign process for benzylation of toluene to mono-benzylated toluene over highly active and stable hierarchical zeolite catalyst. Appl. Petrochem. Res. 5, 113–119 (2015).

Vanjari, R. & Singh, K. N. Utilization of methylarenes as versatile building blocks in organic synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 8062–8096 (2015).

Ma, F., Lei, M. & Hu, L. Acetohydrazone: a transient directing group for arylation of unactivated C(sp3)-H bonds. Org. Lett. 18, 2708–2711 (2016).

Zhang, F.-L., Hong, K., Li, T.-J., Park, H. & Yu, J.-Q. Functionalization of C(sp3)-H bonds using a transient directing group. Science 351, 252–256 (2016).

Vasilopoulos, A., Zultanski, S. L. & Stahl, S. S. Feedstocks to pharmacophores: Cu-catalyzed oxidative arylation of inexpensive alkylarenes enabling direct access to diarylalkanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 7705–7708 (2017).

Zhang, W., Chen, P. & Liu, G. Copper-catalyzed arylation of benzylic C-H bonds with alkylarenes as the limiting reagents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 7709–7712 (2017).

Curto, J. M. & Kozlowski, M. C. Chemoselective activation of sp3 vs sp2 C-H bonds with Pd(II). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 18–21 (2015).

Liu, H., Shi, G., Pan, S., Jiang, Y. & Zhang, Y. Palladium-catalyzed benzylation of carboxylic acids with toluene via benzylic C-H activation. Org. Lett. 15, 4098–4101 (2013).

Hussain, N., Frensch, G., Zhang, J. & Walsh, P. J. Chemo- and regioselective C(sp3)-H arylation of unactivated allylarenes by deprotonative cross-coupling. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 3693–3697 (2014).

Zhang, J. et al. Positional selectivity in C-H functionalizations of 2-benzylfurans with bimetallic catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 4260–4266 (2016).

Sha, S.-C. et al. Nickel-catalyzed allylic alkylation with diarylmethane pronucleophiles: reaction development and mechanistic insights. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 1070–1074 (2016).

Zhang, J. et al. NiXantphos: a deprotonatable ligand for room-temperature palladium-catalyzed cross-couplings of aryl chlorides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 6276–6287 (2014).

Sha, S.-C., Zhang, J., Carroll, P. J. & Walsh, P. J. Raising the pK a limit of soft nucleophiles in palladium-catalyzed allylic substitutions: application of diarylmethane pronucleophiles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 17602–17609 (2013).

Zhang, S., Kim, B.-S., Wu, C., Mao, J. & Walsh, P. J. Palladium-catalysed synthesis of triaryl(heteroaryl)methanes. Nat. Commun. 8, 14641–14648 (2017).

Jia, T. et al. Palladium-catalyzed enantioselective arylation of aryl sulfenate anions: a combined experimental and computational study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 8337–8345 (2017).

Jia, T. et al. Diaryl sulfoxides from aryl benzyl sulfoxides: a single palladium-catalyzed triple relay process. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 260–264 (2014).

Bordwell, F. G. Equilibrium acidities in dimethyl sulfoxide solution. Acc. Chem. Res. 21, 456–463 (1988).

Fraser, R. R., Mansour, T. S. & Savard, S. Acidity measurements on pyridines in tetrahydrofuran using lithiated silylamines. J. Org. Chem. 50, 3232–3234 (1985).

McGrew, G. I. et al. Asymmetric cross-coupling of aryl triflates to the benzylic position of benzylamines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 11510–11513 (2012).

McGrew, G. I., Temaismithi, J., Carroll, P. J. & Walsh, P. J. Synthesis of polyarylated methanes through cross-coupling of tricarbonylchromium-activated benzyllithiums. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 5541–5544 (2010).

Kalinin, V. N., Cherepanov, Iy. A. & K. Moiseev, S. Benzylic functionalization of (η6-alkylarene)chromium tricarbonyl complexes. J. Organomet. Chem. 536/537, 437–455 (1997).

Takemoto, S. et al. Ruthenium-sulfonamide-catalyzed direct dehydrative condensation of benzylic C-H bonds with aromatic aldehydes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 14836–14839 (2016).

Bowden, K. & Cook, R. S. Reactions in strongly basic solutions. VI. Correlation of the rates of rearrangement of weak carbon acids in aqueous methyl sulfoxide with an acidity function. Substituent and kinetic isotope effects. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2, 1407–1411 (1972).

Bao, W., Kossen, H. & Schneider, U. Formal allylic C(sp3)-H bond activation of alkenes triggered by a sodium amide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 4362–4365 (2017).

Suzuki, H., Igarashi, R., Yamashita, Y. & Kobayashi, S. Catalytic direct-type 1,4-addition reactions of alkylazaarenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 4520–4524 (2017).

Yamashita, Y. & Kobayashi, S. Catalytic carbon-carbon bond-forming reactions of weakly acidic carbon pronucleophiles using strong Brønsted bases as catalysts. Chem. Eur. J. 24, 10–17 (2018).

Zhai, D.-D., Zhang, X.-Y., Liu, Y.-F., Zheng, L. & Guan, B.-T. Potassium amide-catalyzed benzylic C-H bond addition of alkylpyridines to styrenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 1650–1653 (2018).

Yamashita, Y., Suzuki, H., Sato, I. & Kobayashi, S. Catalytic direct-type addition reactions of alkylarenes with imines and alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 6896–6900 (2018).

Liu, Y.-F., Zhai, D.-D., Zhang, X.-Y. & Guan, B.-T. Potassium-zincate-catalyzed benzylic C-H bond addition of diarylmethanes to styrenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 8245–8249 (2018).

Giles, M. Process for the preparation of 1-phenyl-2-(2-pyridyl)ethanamine which does not require the use of butyl lithium. WO 2000063175 (2000).

Hart, D. J., Kanai, K., Thomas, D. G. & Yang, T. K. Preparation of primary amines and 2-azetidinones via N-(trimethylsilyl)imines. J. Org. Chem. 48, 289–294 (1983).

Das, M. & O’Shea, D. F. Highly selective addition of a broad spectrum of trimethylsilane pro-nucleophiles to N-tert-butanesulfinyl imines. Chem. Eur. J. 21, 18717–18723 (2015).

Martin, F. et al. Alkaloids from the chinese vine gnetum montanum. J. Nat. Prod. 74, 2425–2430 (2011).

Wink, C. S. D., Meyer, G. M. J., Meyer, M. R. & Maurer, H. H. Toxicokinetics of lefetamine and derived diphenylethylamine designer drugs-contribution of human cytochrome P450 isozymes to their main phase I metabolic steps. Toxicol. Lett. 238, 39–44 (2015).

Natsuka, K., Nakamura, H., Negoro, T., Uno, H. & Nishimura, H. Studies on 1-substituted 4-(1,2-diphenylethyl)piperazine derivatives and their analgesic activities. 2. Structure-activity relationships of 1-cycloalkyl-4-(1,2-diphenylethyl)piperazines. J. Med. Chem. 21, 1265–1269 (1978).

Panunzio, M. & Zarantonello, P. Synthesis and use of N-(trimethylsilyl)imines. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2, 49–59 (1998).

Posner, G. H. & Lentz, C. M. A directing effect of neighboring aromatic groups on the regiochemistry of formation and stereochemistry of alkylation and bromination of ketone lithium enolates. Evidence for lithium-arene coordination and dramatic effect of copper(I) in controlling stereochemistry and limiting polyalkylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 101, 934–946 (1979).

Ojeda-Amador, A. I., Martinez-Martinez, A. J., Kennedy, A. R. & O’Hara, C. T. Structural studies of cesium, lithium/cesium, and sodium/cesium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide (HMDS) complexes. Inorg. Chem. 55, 5719–5728 (2016).

Ojeda-Amador, A. I., Martinez-Martinez, A. J., Kennedy, A. R. & O’Hara, C. T. Synthetic and structural studies of mixed sodium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide/sodium halide aggregates in the presence of η2-N,N -, η3-N,N,N/N,O,N-, and η4-N,N,N,N-donor ligands. Inorg. Chem. 54, 9833–9844 (2015).

Edelmann, F. T., Pauer, F., Wedler, M. & Stalke, D. Preparation and structural characterization of dioxane-coordinated alkali metal bis(trimethylsilyl)amides. Inorg. Chem. 31, 4143–4146 (1992).

Klinkhammer, K. W., Klett, J., Xiong, Y. & Yao, S. Homo- and heteroleptic hypersilylcuprates - valuable reagents for the synthesis of molecular compounds with a Cu-Si bond. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2003, 3417–3424 (2003).

Andrikopoulos, P. C. et al. Synthesis, structure and theoretical studies of the hydrido inverse crown [K2Mg2(NiPr2)4(μ-H)2·(toluene)2]: a rare example of a molecular magnesium hydride with a Mg-(μ-H)2-Mg double bridge. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2003, 3354–3362 (2003).

Gokel, G. W. The aromatic sidechains of amino acids as neutral donor groups for alkali metal cations. Chem. Commun. 3, 2847–2852 (2003).

Pospisil, J. & Marko, I. E. Total synthesis of Jerangolid D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 3516–3517 (2007).

Purser, S., Moore, P. R., Swallow, S. & Gouverneur, V. Fluorine in medicinal chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 37, 320–330 (2008).

Ruiz-Castillo, P. & Buchwald, S. L. Applications of palladium-catalyzed C-N cross-coupling reactions. Chem. Rev. 116, 12564–12649 (2016).

Chan, L.-H. & Rochow, E. G. Syntheses and ultraviolet spectra of N-organosilyl ketimines. J. Organo. Chem. 9, 231–250 (1967).

Hoffmann, D. et al. η 3 and η 6 Bridging cations in the N,N,N’,N”,N”-pentamethyldiethylenetriamine-solvated complexes of benzylpotassium and benzylrubidium: an x-ray, NMR, and MO study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 116, 528–536 (1994).

Konya, K., Pajtas, D., Kiss-Szikszai, A. & Patonay, T. Buchwald-Hartwig reactions of monohaloflavones. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 828–839 (2015).

Ullrich, J. W. Preparation of N-substituted indolines as estrogenic agents. WO 2000051982 (2000).

Wink, C. S. D., Meyer, G. M. J., Zapp, J. & Maurer, H. H. Lefetamine, a controlled drug and pharmaceutical lead of new designer drugs: synthesis, metabolism, and detectability in urine and human liver preparations using GC-MS, LC-MSn, and LC-high resolution-MS/MS. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 407, 1545–1557 (2015).

Banerjee, S. et al. Ionic and neutral mechanisms for C-H bond silylation of aromatic heterocycles catalyzed by potassium tert-butoxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 6880–6887 (2017).

Toutov, A. A. et al. Silylation of C-H bonds in aromatic heterocycles by an earth-abundant metal catalyst. Nature 518, 80–84 (2015).

Pardue, D. B., Gustafson, S. J., Periana, R. A., Ess, D. H. & Cundari, T. R. Computational study of carbon-hydrogen bond deprotonation by alkali metal superbases. Comput. Theor. Chem. 1019, 85–93 (2013).

Ma, J. C. & Dougherty, D. A. The cation-π interaction. Chem. Rev. 97, 1303–1324 (1997).

Kumpf, R. A. & Dougherty, D. A. A mechanism for ion selectivity in potassium channels: computational studies of cation-π interactions. Science 261, 1708–1710 (1993).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the start-up grant of Nanjing Tech University (3980001601 to P.J.W. and 39837112 to J.M.) and Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province, China (BK20170965) for financial support. P.J.W. thanks the US National Science Foundation (CHE-1464744). The authors are grateful for financial support by SICAM Fellowship by Jiangsu National Synergetic Innovation Center for Advanced Materials. Prof. Peng Cui (Anhui Normal University), Prof. Lili Zhao (Nanjing Tech University), and Dr. Haolin Yin (Caltech University) are thanked for helpful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.W., X.X., Z.Z., and J.M. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. J.M. and P.J.W. conceived the project and wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Z., Zheng, Z., Xu, X. et al. One-pot aminobenzylation of aldehydes with toluenes. Nat Commun 9, 3365 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-05638-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-05638-y

This article is cited by

-

Direct alkylation of N,N-dialkyl benzamides with methyl sulfides under transition metal-free conditions

Communications Chemistry (2021)

-

Asymmetric C(sp3)–H functionalization of unactivated alkylarenes such as toluene enabled by chiral Brønsted base catalysts

Communications Chemistry (2021)

-

Benzylic aroylation of toluenes with unactivated tertiary benzamides promoted by directed ortho-lithiation

Science China Chemistry (2021)

-

Copper-catalysed benzylic C–H coupling with alcohols via radical relay enabled by redox buffering

Nature Catalysis (2020)

-

Copper-catalyzed oxidative benzylic C-H cyclization via iminyl radical from intermolecular anion-radical redox relay

Nature Communications (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.