Abstract

Many heterogeneous catalytic reactions occur at high temperatures, which may cause large energy costs, poor safety, and thermal degradation of catalysts. Here, we propose a light-assisted surface reaction, which catalyze the surface reaction using both light and heat as an energy source. Conventional metal catalysts such as ruthenium, rhodium, platinum, nickel, and copper were tested for CO2 hydrogenation, and ruthenium showed the most distinct change upon light irradiation. CO2 was strongly adsorbed onto ruthenium surface, forming hybrid orbitals. The band gap energy was reduced significantly upon hybridization, enhancing CO2 dissociation. The light-assisted CO2 hydrogenation used only 37% of the total energy with which the CO2 hydrogenation occurred using only thermal energy. The CO2 conversion could be turned on and off completely with a response time of only 3 min, whereas conventional thermal reaction required hours. These unique features can be potentially used for on-demand fuel production with minimal energy input.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metal nanoparticles loaded onto supports have been typically used as heterogeneous catalysts for surface reactions such as hydrogenation, oxidation, reforming, and coupling reactions1,2,3,4,5. Surface reactions often require high temperatures to overcome the activation energy barrier. Operating the reactor at a high temperature may demand excessive energy and stringent safety controls. Recently, light-assisted surface reactions have been reported6,7,8,9,10,11. Using heat and light together as two different energy sources might minimize the overall energy usage and provide unique features, which cannot be provided by conventional thermal catalytic reactions.

Enhancing the catalytic activity under light irradiation has been reported for heterogeneous reactions including ethylene epoxidation on Ag nanocubes, reverse water–gas shift reaction on Al@Cu2O, ethanol dehydrogenation on Ag–Ni nanosnowmans6,7,8. Light is absorbed on the catalyst and then transferred to reactant molecules on the surface by heat or hot electrons. The photothermal effect, in which absorbed light energy is relaxed as heat, would occur only with a very strong light that is orders of magnitude higher than the intensity of sunlight12,13,14,15.

Hot electrons are generated on metal nanoparticles by an intraband or interband transition upon light absorption. Localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) is a typical intraband transition that can be derived from metals with high electron mobility in sp-band. Group IB metals such as Au, Ag, and Cu are representative plasmonic metals and other transition metals also can have LSPR occasionally8,9,16,17,18. Non-plasmonic metal nanoparticles can produce hot electrons by interband transition, in which electrons are excited from d-band to unoccupied conduction band19,20,21,22. However, light absorption by the interband transition is usually weak, and it is effective only under UV light. When the hot electrons contribute to the surface reaction, the catalytic activity for various wavelengths of incident light typically follows the trend of their light absorption spectra. With an increase in the light absorption, more hot electrons are produced, thereby enhancing the catalytic reaction further.

However, this analogy might not be applicable when light is absorbed by direct excitation of the electrons located at the hybrid orbitals of a reactant adsorbed on a metal surface. When a reactant molecule is strongly adsorbed on a metal, the energy levels of electronic orbitals are rearranged. If the energy gap between the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) is reduced, then the incident light can excite the electrons on the hybrid orbitals promoting the surface reaction10,23,24,25. Christopher et al. reported that CO oxidation in a H2-rich stream can be promoted by direct photoexcitation of adsorbate (CO)–metal (Pt) bonds10. Zhu et al. also observed selective oxidation of aliphatic alcohols on Pt or Pd nanoparticles under visible light irradiation11.

Here, we show that CO2 hydrogenation is enhanced on the Ru surface under light irradiation. The effects of the metal type, Ru domain size, and Ru oxidation state are evaluated. The DFT calculation is performed to investigate the changes in the energy gap between the HOMO and LUMO levels for various metals. Light irradiation reduces the reaction temperature significantly minimizing the total energy usage for CO2 hydrogenation. Additionally, the reaction can be turned on or off in a moment, unlike the conventional thermal reaction.

Results

Enhancement in activity upon light irradiation

Various metals (i.e., Ru, Rh, Pt, Ni, and Cu) were deposited on silica supports using a wet impregnation method. The TEM images of the catalysts were shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. The size of the metal nanoparticles was controlled to be between 5 and 7 nm by changing the weight percentages of the metals as shown in Supplementary Table 1. The powder catalysts containing 10 mg of metal were loaded into the custom-made photoreactor. A schematic of the reactor set-up and its photograph are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. CO2 hydrogenation was performed by flowing CO2 and H2 together after reducing the catalysts at 300 °C for 3 h. Figure 1 shows the CO2 conversion data of various metals with and without light irradiation (Supplementary Table 2 for the full data). Ru and Rh produced CH4 only, whereas Pt and Cu produced CO only. Ni produced 89% CO and 11% CH4. The CO2 conversion increased upon light irradiation for Ru and Rh, while the conversion did not change for Pt, Ni, and Cu. Especially, the Ru catalyst showed remarkable enhancements. At 150 °C, the CO2 conversion was 1.6% without light, but it increased to 32.6% with light. This conversion was obtained at 230 °C without light. By simply shining light, the reaction temperature for CO2 hydrogenation was lowered significantly. When a higher concentration of CO2 was used with CO2/N2/H2 flow rates of 5/30/15 sccm, the CO2 conversion was also significantly enhanced from 1.1 to 10.9% at 150 °C upon light irradiation as shown in Supplementary Fig. 3. Supplementary Table 3 shows the comparison of the production rate with the literature values reported for gas-phase CO2 hydrogenation performed under light irradiation13,26,27,28,29.

Light enhancement on metal catalysts. CO2 conversion for CO2 hydrogenation on a Ru, b Rh, and c Pt, Ni, and Cu catalysts deposited onto silica with and without light irradiation. 0.5 vol% CO2/N2 (50 sccm) and H2 (1.5 sccm) was fed into the reactor through a static mixer with or without light irradiation. A Xe lamp with light intensity of 35 mW cm−2 was used with a water-circulating filter to exclude any thermal effect from the light source. The error bar indicates the deviation among three independent measurements

The light intensity during the CO2 hydrogenation was 35 mW cm−2, which is too weak to induce any photothermal effect. The photothermal effect has been observed in a light intensity range of 1–106 W cm−2, regardless of the metal type12,13,14,15,30. The intensity of sunlight is ~100 mW cm-2. A linear relation between the photocatalytic activity and light intensity has been well known as a fingerprint for hot electron-driven chemical reactions7,8,31,32. Figure 2a and b shows that the CO2 conversion increased linearly as the light intensity increased on the Ru or Rh catalysts. Clearly, the light-enhanced CO2 hydrogenation results from the hot electrons.

Dependence on light intensity and light wavelength. a, b CO2 conversion for CO2 hydrogenation on Ru/SiO2 and Rh/SiO2 when the light intensity was varied. To clarify the relation between the light intensity and CO2 conversion enhanced by the light, thermal CO2 conversion without light was subtracted from light-assisted CO2 conversion (ΔCO2 conversion). Light intensity after passing the sapphire window was measured by a spectroradiometer. c, d In-situ UV–Vis spectroscopy in CO2 flow (black lines) and quantum yield for wavelength-dependent measurement of CO2 hydrogenation on Ru/SiO2 or Rh/SiO2 (red or blue dots). Error bars in x-direction indicates full-width at half maximum intensity of monochromatic light. Error bars in y-direction indicates a deviation among three different measurements. The in-situ UV–Vis spectroscopy and CO2 conversion was measured at 150 °C for Ru/SiO2 and 200 °C for Rh/SiO2

The silica support is photochemically inert; thus, Ru or Rh should provide hot electrons. The extent of the surface oxide was changed to observe the effect of the surface oxide for the light enhancement. While the as-made Ru/SiO2 catalyst with a Ru size of 5.6 nm has 89% of metallic Ru and 11% of Ru oxide at the surface, the percentages of Ru oxide increased to 44 and 61% after annealing the catalyst at 500 °C in air for 1 and 60 min, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 4). Supplementary Fig. 5 shows the CO2 conversion data for these samples having different amounts of Ru oxide with and without light irradiation. The enhancement from the light decreased drastically as the amount of Ru oxide increased, and the sample annealed for 60 min showed little enhancement upon light irradiation. This indicates that metallic Ru is responsible for the enhancement by light.

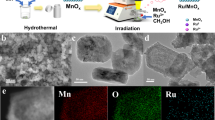

The effect of the Ru nanoparticle size was estimated. Different sizes (2.6, 5.6, and 17.1 nm) of Ru nanoparticles were obtained by changing the weight percentages of Ru on the Ru/SiO2 catalyst, and their TEM images are shown in Supplementary Fig. 6. The nanoparticle sizes were checked using both powder XRD and the H2 uptakes as shown in Supplementary Table 4. The fraction of metallic Ru on the surface was the same as ~90%. Supplementary Fig. 7 shows that the enhancement by light was much smaller in the 2.6 nm Ru nanoparticles, while both the 5.6 and 17.1 nm Ru nanoparticles had a distinct enhancement. It was reported that larger Ru nanoparticles (e.g., ≥5 nm) exhibit a higher CO2 conversion than smaller ones for conventional CO2 hydrogenation because CO2 dissociation requires higher activation barrier on smaller Ru nanoparticles33,34,35. Thus, we hypothesized that the enhancement by light may be related to the interaction between the Ru surface and the CO2 molecule.

Hot electrons can be produced on a metal surface by an intraband or interband transition8,9,16,17,18,19,20,21,22. Among Ru, Rh, Pt, Ni, and Cu, only Cu can have an intraband transition; however, the Cu catalyst did not show any enhancement for CO2 hydrogenation under light. If hot electrons produced by the interband transition promote CO2 hydrogenation, all the metals, not just Ru or Rh, should show an enhancement. Additionally, the interband transition is usually observed in the ultraviolet (UV) range, and the enhancement by the interband transition decreases abruptly as the wavelength of the incident light increases20,22. In-situ UV–Vis spectroscopy was performed in CO2 flow as shown in Fig. 2c, d (black lines). While UV-DRS data (Supplementary Fig. 8) obtained without CO2 showed no peak, the peaks were observed at 528 nm for Ru/SiO2 and 410 nm for Rh/SiO2. When the content of Ru/SiO2 catalyst in KBr mixture increased, the absorbance also increased without the change in peak position as shown in Supplementary Fig. 9. Interestingly, these spectra from in-situ UV–Vis measurements (black lines) agree well with the photoaction spectra, which are the plots of quantum yield (QY) vs. wavelength (red or blue dots in Fig. 2c, d). The QY was estimated from the CO2 hydrogenation reaction data at each wavelength using a monochromator. Briefly, QY was calculated by dividing the number of converted CO2 molecules with the number of incident photons at each wavelength (Supplementary Fig. 10). The detailed procedure is explained in Methods. The photoaction spectra also presented peaks at 520 nm for Ru/SiO2 and 420 nm for Rh/SiO2. This result indicates that the hot electrons originate from light absorption by CO2 adsorbed on the metallic Ru or Rh surface and they promote the CO2 hydrogenation.

Mechanism study

The CO2 binding energy on various metal surfaces was estimated using density functional theory (DFT) calculations, as shown in Fig. 3a. (111) surface was used for the face-centered cubic metals of Rh, Pt, Ni, and Cu, while (0001) surface was used for the hexagonal close packed metal of Ru. Various CO2 positions were tested to obtain the minimum energy configuration as shown in Supplementary Fig. 11. Figure 3a shows the values of the lowest CO2 binding energy. Supplementary Fig. 12 shows the state of CO2 with the lowest energy configurations. Ru and Rh have a negative binding energy, while Pt, Ni, Cu have a positive binding energy, indicating that CO2 binds onto the Ru or Rh surface strongly while it does not bind to the other metal surfaces. This trend in CO2 binding energy on various metal catalyst agrees well with CO2 chemisorption results shown in Supplementary Table 5 and other previous report36. The strong adsorption of CO2 onto the Ru or Rh surface may change the electronic structure of the CO2. The electronic structure of free CO2 and CO2 adsorbed on the metal surface were calculated, and their HOMO (5σ bonding)–LUMO (2π anti-bonding) gaps are shown in Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 11c. The gap decreased significantly from 8.5 eV for free CO2 to 2.4 eV for CO2 adsorbed on the Ru surface. The energy gap of the CO2 adsorbed on the Rh surface was 2.8 eV. These gaps are small enough for the electrons to jump under visible light irradiation. The gap was much larger as 4.5 eV for Ni, 3.8 eV for Pt, and 3.5 eV for Cu. In Fig. 2c and d, Ru had the absorption peak in the presence of CO2 at 528 nm (~2.3 eV) and Rh had the peak at 410 nm (~3.0 eV). The calculated energy gaps of 2.4 eV for Ru and 2.8 eV for Rh are in good agreement with the experimentally obtained values.

Binding of CO2 on metal surfaces. a CO2 binding energy and b HOMO-LUMO gap of free CO2, adsorbed CO2 on the Ru surface, or adsorbed CO2 on the Rh surface, obtained using DFT calculations. c DRIFT spectra for CO2 adsorption on Ru/SiO2 with or without light irradiation. 50 sccm of 0.5% CO2/N2 was flowed for 10 min; the cell was purged with 60 sccm of N2 for 15 min to desorb the weakly adsorbed CO2, and the IR spectra were obtained

The diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform (DRIFT) spectra for CO2 adsorbed on the Ru surface are shown in Fig. 3c. The spectra obtained with and without light were compared. Whereas no peak appeared up to 200 °C without light, two distinct peaks were observed at 1950 and 1800 cm−1 even at 100 °C with light. The peak at 1950 cm−1 resulted from CO linearly adsorbed on Ru, and the peak at 1800 cm−1 indicated that CO was adsorbed on Ru through a bridge mode37,38. Upon light irradiation, CO2 would be cleaved to COad and Oad on the Ru surface. Supplementary Fig. 13 shows the DRIFT spectra obtained when H2 was additionally flowed after the CO2 was adsorbed on the Ru surface. The two peaks appeared at 150 °C without light, indicating that H2 assists in CO2 dissociation. However, the peaks were much larger with light, confirming that light irradiation clearly promoted CO2 dissociation.

The effect of light on CO hydrogenation was also investigated. Supplementary Fig. 14a shows the CO conversion data with and without light. The CO conversion was slightly higher under light irradiation, but the differences in the conversion with and without light were rather small. Supplementary Fig. 14b shows the DRIFT spectra when CO was adsorbed on the Ru surface, and Supplementary Fig. 14c shows the DRIFT spectra when H2 was additionally flowed after adsorbing CO onto the Ru surface. The spectra were almost identical, regardless of the light irradiation. CO hydrogenation was hardly affected by light irradiation, indicating that the enhanced activity upon light irradiation for CO2 hydrogenation is related to the CO2 dissociation. When CO2 is strongly adsorbed on the Ru surface, hybrid orbitals are formed with a much shorter energy gap. If the light can easily excite the electrons in the bonding orbitals to anti-bonding orbitals, then CO2 can be dissociated to CO. Further hydrogenation would produce CH4.

Kinetic analysis of light-assisted CO2 hydrogenation was performed with various CO2 partial pressures and temperatures. Supplementary Fig. 15a shows the dependences of CO2 conversion rates on the partial pressure of CO2. The CO2 conversion rate increased as the CO2 partial pressure increased, and reached a plateau at 4 kPa of CO2. The CO2 conversion rate followed the identical saturation behaviors under light irradiation, reaching the plateau at the same CO2 partial pressure. It indicates that the light irradiation did not change CO2 coverage on Ru surface, but interfere with the adsorbed CO2 species. The temperature dependence of CO2 hydrogenation around 150 °C was investigated as shown in Supplementary Fig. 15b. Without light, the effective energy barrier (Ea) of Ru catalyst was 70.4 kJ mol−1, which agrees well with previous studies39,40. However, the Ea decreased significantly to 36.2 kJ mol−1 with light irradiation. The incident light lowers the effective energy barrier on Ru catalyst for CO2 hydrogenation.

Comparing energy usage for thermal vs. light-assisted reactions

The same CO2 conversion can be achieved at a lower temperature with light. If the power required to shine light is less than the power required to heat the reactor, the overall energy consumption would be reduced. Figure 4a shows the total energy consumption for CO2 hydrogenation with and without light. The reactor temperature was set to be 180 °C for the case without light, and 150 °C for the case with light. The CO2 conversion was maintained at ~15% for both cases. The total electric power consumed was measured by an online power meter. To minimize the energy consumption for shining a light, a compact laser with a wavelength of 532 nm was used with a beam expander instead of a Xe lamp. For a CO2 hydrogenation reaction for 8 h, the total energy consumption was 5411 kJ for the case without light, and 2020 kJ for the case with light. Only 37% of the energy was consumed when light was irradiated together. Clearly, the energy required for catalytic reactions in a continuous flow reactor can be significantly reduced by light irradiation.

Energy usage and response for CO2 hydrogenation with or without light irradiation. a Energy consumption during CO2 hydrogenation with or without light irradiation. The condition in which both cases showed similar CO2 conversions was chosen; CO2 hydrogenation occurred at 180 °C without light, or 150 °C with light. 100 mW laser (532 nm) equipped with a beam expander was used as a light source. The overall power consumption was measured by a power meter. b Response test results for CO2 hydrogenation with or without light. At t = 0, the temperature of the reactor was set at 100 °C. In the case without light, the heater was turned on, the temperature was maintained for 3 h after it reached 250 °C, and the heater was turned off. In the case with light, a Xe lamp with a light intensity of 63 mW cm−2 was turned on for 15 min and turned off for 15 min repeatedly

In a thermally heated reactor, controlling the temperature instantaneously is nearly impossible. Figure 4b shows the response in CO2 conversion for turning on or off the heater or light source. When the heater was turned on at t = 0, it took 52 min to reach the target temperature of 250 °C and the highest conversion. More importantly, cooling down the reactor took much longer time. After the heater was turned off at t = 3.8 h, CO2 conversion was still observed with a long tail due to the residual heat in the reactor. However, the response became much faster with light irradiation. The highest conversion was immediately obtained after turning on the lamp. The CO2 conversion dropped to 0% within 3 min after turning off the lamp. The instantaneous control of CO2 conversion cannot be achieved with a conventional thermal reactor. This unique feature might be useful for on-demand CH4 production.

Discussion

CO2 hydrogenation was performed on metallic catalysts of Ru, Rh, Pt, Ni, and Cu with and without light irradiation. The CO2 conversion was enhanced significantly on a Ru catalyst by light irradiation. The CO2 conversion was 1.6% at 150 °C without light on Ru, but the conversion increased to 32.6% at 150 °C with light. The effects of the Ru surface oxidation state and Ru nanoparticle size were evaluated. The light-enhancement appeared only at the metallic Ru surface, and larger nanoparticles exhibited more enhancement. Hot electrons generated upon light irradiation enhanced the CO2 conversion; however, the enhancement was not related to the light absorption on the metal surface. Rather, it was related to the HOMO-LUMO energy gap of the CO2 adsorbed on the metal surface. DFT calculations showed that CO2 is strongly bound to the Ru surface, and the energy gap is reduced from 8.5 eV in free CO2 to 2.4 eV in CO2 adsorbed on the Ru surface. Especially, light promotes CO2 dissociation to CO as confirmed by the DRIFTS data. Light irradiation could lower the reaction temperature for CO2 hydrogenation. When total energy consumption was compared at a CO2 conversion rate of 15%, the energy required for the case with light irradiation was only 37% of that for the case without light irradiation. Furthermore, the CO2 conversion could be instantaneously turned on and off by light irradiation unlike a conventional thermal reaction. This light-assisted heterogeneous reaction can contribute to lowering energy consumption in chemical production, with a much faster response for the changes in the reaction condition.

Methods

Catalyst synthesis

Metal nanoparticle catalysts supported on silica (M/SiO2, M = Pt, Ni, Cu, Ru, and Rh) were prepared using a wet impregnation method. Different amounts of metal precursors, (metal acetylacetonates; details in Supplementary Table 1) were dissolved in acetone (10 mL, Sigma-Aldrich) and added to silica nanopowder (1 g, Sigma-Aldrich). The slurry mixture was dried at 80 °C for 30 min, and it was placed into the furnace and heated up to 300 °C with a ramping rate of 10 °C min-1 in 10 vol% H2/N2 (200 sccm). Then, catalysts were reduced at 300 °C for 3 h. The extent of the surface oxidation on Ru/SiO2 was controlled by oxidizing the catalyst at 500 °C under static air for various treatment times (1 or 60 min).

CO2 hydrogenation

The M/SiO2 (M = Pt, Ni, Cu, Ru, and Rh) catalysts were placed in a cylindrical quartz sample holder (2 cm of diameter). Metal 10 mg was loaded for all the reactions. The sample holder was placed in a customized photoreactor equipped with a sapphire glass window (a thickness of 23 mm) as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. It should be noted that a water circulating filter was located in front of the Xe lamp (300 W, Newport) to exclude the effect of thermal radiation from the lamp. The catalysts were reduced prior to the CO2 hydrogenation for 3 h at 300 °C under 10 vol% H2/N2 flow. In a typical CO2 hydrogenation, a mixture of 0.5 vol% CO2/N2 (50 sccm) and H2 (1.5 sccm) was fed into the reactor through a static mixer with or without light irradiation at atmospheric pressure. The CO2 conversion was monitored by an online gas chromatograph (YL6100 GC, YL Instrument) equipped with molesieve/PORAPAK N columns (Sigma-Aldrich), a thermal conductivity detector (for H2 and N2 detection), and a flame ionization detector (for CH4, CO, and CO2 detection) with a methanizer. Quantitative analysis was performed using N2 as an internal standard. The dependency on the light intensity or light wavelength was measured at 150 °C for Ru and 200 °C for Rh. The light intensity was varied by changing the electric power of the lamp and measured by a spectroradiometer (CS2000, KONICA MINOLTA). The transmittances of the liquid filter and the sapphire glass window are shown in Supplementary Fig. 16a,b. The light intensity was corrected excluding the effect of the liquid filter and the sapphire glass window. The photoaction spectra were obtained using a monochromator (MonoRa151i, Dongwoo Optron) with wavelengths shown in Supplementary Fig. 16c. A 532 nm laser (100 mW, CNI laser) was used as the light source for the energy consumption test.

Estimation of the QY

The energy of the irradiated light for a given time is:

where n is a number of incident photon, λ is a wavelength of incident photon, h is Planck constant, c is a speed of light, I is the light intensity, A is the area of irradiation, and s is irradiation time. Then incident photon flux is defined as:

The QY can be estimated as:

where \(n_{{\mathrm{CO}}_2}\) is the number of the converted CO2 molecules. The wavelength-dependent measurement was performed using a monochromator (MonoRa151i, Dongwoo Optron). In prior to the measurement, the monochromatic light was calibrated with a spectrometer (Maya 2000 Pro, Ocean Optics) as shown in Supplementary Fig. 16c. The intensity of the monochromatic light was measured with an optical power meter (PM204, Thorlab) after the monochromatic light passed through a sapphire window of the reactor. The catalytic activity under the monochromatic light irradiation was measured at steady state for CO2 hydrogenation. The rate of the CO2 molecules converted by the incident photon was estimated excluding the CO2 conversion from thermal reaction.

Characterizations

The morphology of prepared catalysts was observed using HR-TEM (TECNAI). A powder X-ray diffractometer (SmartLab, RIGAKU) was used to determine the crystalline size of the metal nanoparticles. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Thermo VG Scientific) equipped with a monochromatic Al Kα X-ray source was used to measure the surface properties of metal nanoparticles. The binding energies were calibrated with adventitious C 1 s signal at 285 eV as a reference. The absorption spectra of the metal catalysts were obtained using an UV-diffuse reflectance spectrometer (UV-DRS) (UV3600, Shimadzu). Elemental analysis was conducted using an inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometer (ICP-OES 720, Agilent) to confirm the actual metal content in the M/SiO2 catalysts. In situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS) measurements were performed using a FT-IR spectrometer (Thermo, Nicolet 6700) equipped with a MCT detector. In situ UV–Vis spectroscopy was performed using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Perkin Elmer, lambda 1050) equipped with diffuse reflectance accessory (PIKE, DiffuseIR) enabling gas flow and temperature control. The power consumption during the CO2 hydrogenation was monitored using a 2-channel power meter (WT500, YOKOGAWA) which contacted both furnace and light sources. The energy consumption by the standby power was excluded for both cases.

Theoretical calculation using DFT

All of the quantum chemical calculations were performed with the Vienna ab initio simulation package41. We used the projector augmented wave pseudopotentials with Perdew–Burke Ernzerhof42 exchange correlation functional. The energy cutoff was set as 500 eV, while a 5 × 5 × 1 k-point grid was used for energy relaxation, and 20 × 20 × 1 for the density of states calculation using the Monkhorst–Pack scheme43. Five metal catalysts (Cu, Ni, Pt, Rh, and Ru) were modeled using four layered slabs with the surfaces of (111) used for Cu, Ni, Pt, and Rh, and (0001) for Ru with a 15 Å vacuum region. Only the atoms from the top layer could relax during the DFT simulations. The CO2 molecules were initialized on different atomic sites (Supplementary Fig. 11), and the binding energy was determined by the lowest energy configurations (Supplementary Fig. 12). The angles of the CO2 molecules are slightly bent due to the strong interaction between the metal surfaces and the CO2 molecule. The CO2 binding energy was defined as follows:

where \(E_{{\mathrm{bind}}}\) is the binding energy of CO2 on the metal catalyst, and \(E_{{\mathrm{catalyst}} + {\mathrm{CO}}_2}\) is the total energy of the metal catalyst with a single CO2 molecule. \(E_{{\mathrm{catalyst}}}\) and \(E_{{\mathrm{CO}}_2}\) are the total energy of free metal catalyst and CO2 molecule, respectively.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files.

References

Rase, H. F. Handbook of Commercial Catalysts: Heterogeneous Catalysts (CRC Press, Boca Raton, 2000).

Han, J. W. et al. Highly coke-resistant Ni nanoparticle catalysts with minimal sintering in dry reforming of methane. ChemSusChem 7, 451–456 (2014).

Mallat, T. et al. Oxidation of alcohols with molecular oxygen on solid catalysts. Chem. Rev. 104, 3037–3058 (2004).

Son, S. U. et al. Designed synthesis of atom-economical Pd/Ni bimetallic nanoparticle-based catalysts for sonogashira coupling reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 5026–5027 (2004).

Younas, M. et al. Recent advancements, fundamental challenges, and opportunities in catalytic methanation of CO2. Energy Fuels 30, 8815–8831 (2016).

Robatjazi, H. et al. Plasmon-induced selective carbon dioxide conversion on Earth-abundant aluminum-cuprous oxide antenna-reactor nanoparticles. Nat. Commun. 8, 27 (2017).

Kim, C. et al. Surface plasmon aided ethanol dehydrogenation using Ag–Ni binary nanoparticles. ACS Catal. 7, 2294–2302 (2017).

Christopher, P. et al. Visible-light-enhanced catalytic oxidation reactions on plasmonic silver nanostructures. Nat. Chem. 3, 467–472 (2011).

Kim, Y. et al. Activation energies of plasmonic catalysts. Nano Lett. 16, 3399–3407 (2016).

Kale, M. J. et al. Controlling catalytic selectivity on metal nanoparticles by direct photoexcitation of adsorbate–metal bonds. Nano Lett. 14, 5405–5412 (2014).

Tana, T. et al. Non-plasmonic metal nanoparticles as visible light photocatalysts for the selective oxidation of aliphatic alcohols with molecular oxygen at near ambient conditions. Chem. Commun. 52, 11567–11570 (2016).

Keblinski, P. et al. Limits of localized heating by electromagnetically excited nanoparticles. J. Appl. Phys. 100, 054305 (2006).

Meng, X. et al. Photothermal conversion of CO2 into CH4 with H2 over group Viii nanocatalysts: an alternative approach for solar fuel production. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 11478–11482 (2014).

Qiu, J. et al. Surface plasmon-mediated photothermal chemistry. J. Phys. Chem. C 118, 20735–20749 (2014).

Yen, C.-W. et al. Plasmonic field effect on the hexacyanoferrate (iii)-thiosulfate electron transfer catalytic reaction on gold nanoparticles: electromagnetic or thermal? J. Phys. Chem. C 113, 19585–19590 (2009).

Marimuthu, A. et al. Tuning selectivity in propylene epoxidation by plasmon mediated photo-switching of Cu oxidation state. Science 339, 1590–1593 (2013).

Pirzadeh, Z. et al. Plasmon–interband coupling in nickel nanoantennas. ACS Photonics 1, 158–162 (2014).

Zhang, H. et al. Surface-plasmon-enhanced photodriven CO2 reduction catalyzed by metal–organic-framework-derived iron nanoparticles encapsulated by ultrathin carbon layers. Adv. Mater. 28, 3703–3710 (2016).

Anatoliy, P. et al. Influence of interband electronic transitions on the optical absorption in metallic nanoparticles. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 37, 3133 (2004).

Creighton, J. A. et al. Ultraviolet-visible absorption spectra of the colloidal metallic elements. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 87, 3881–3891 (1991).

Pinchuk, A. et al. Optical properties of metallic nanoparticles: influence of interface effects and interband transitions. Surf. Sci. 557, 269–280 (2004).

Sarina, S. et al. Viable photocatalysts under solar-spectrum irradiation: nonplasmonic metal nanoparticles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 2935–2940 (2014).

Huang, M. et al. Co adsorption and oxidation on ceria surfaces from Dft+U calculations. J. Phys. Chem. C 112, 8643–8648 (2008).

Lindstrom, C. D. et al. Photoinduced electron transfer at molecule−metal interfaces. Chem. Rev. 106, 4281–4300 (2006).

Marek, G. et al. Co adsorption on close-packed transition and noble metal surfaces: trends from ab initio calculations. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 16, 1141 (2004).

Thampi, K. R. et al. Methanation and photo-methanation of carbon dioxide at room temperature and atmospheric pressure. Nature 327, 506 (1987).

O’Brien, P. G. et al. Photomethanation of gaseous CO2 over Ru/Silicon nanowire catalysts with visible and near‐infrared photons. Adv. Sci. 1, 1400001 (2014).

Tahir, M. et al. Performance analysis of nanostructured NiO–In2O3/TiO2 catalyst for CO2 photoreduction with H2 in a monolith photoreactor. Chem. Eng. J. 285, 635–649 (2016).

Sastre, F. et al. Complete photocatalytic reduction of CO2 to methane by H2 under solar light irradiation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 6798–6801 (2014).

Chen, G. et al. Alumina-supported CoFe alloy catalysts derived from layered- double-hydroxide nanosheets for efficient photothermal CO2 hydrogenation to hydrocarbons Adv. Mater.. 30, 1704663. (2018).

Christopher, P. et al. Singular characteristics and unique chemical bond activation mechanisms of photocatalytic reactions on plasmonic nanostructures. Nat. Mater. 11, 1044–1050 (2012).

Zhang, C. et al. Al–Pd nanodisk heterodimers as antenna–reactor photocatalysts. Nano Lett. 16, 6677–6682 (2016).

Abdel-Mageed, A. M. et al. Selective CO methanation in CO2-rich H2 atmospheres over a Ru/Zeolite catalyst: the influence of catalyst calcination. J. Catal. 298, 148–160 (2013).

Abdel-Mageed, A. M. et al. Selective CO methanation on Ru/TiO2 catalysts: role and influence of metal–support interactions. ACS Catal. 5, 6753–6763 (2015).

Eckle, S. et al. Influence of the catalyst loading on the activity and the CO selectivity of supported Ru catalysts in the selective methanation of CO in CO2 containing feed gases. Catal. Today 181, 40–51 (2012).

Bligaard, T. et al. The Brønsted–Evans–Polanyi relation and the volcano curve in heterogeneous catalysis. J. Catal. 224, 206–217 (2004).

Panagiotopoulou, P. et al. Mechanistic study of the selective methanation of CO over Ru/TiO2 catalyst: identification of active surface species and reaction pathways. J. Phys. Chem. C 115, 1220–1230 (2011).

Xu, J. et al. Influence of pretreatment temperature on catalytic performance of rutile TiO2-supported ruthenium catalyst in CO2 methanation. J. Catal. 333, 227–237 (2016).

Brooks, K. P. et al. Methanation of carbon dioxide by hydrogen reduction using the sabatier process in microchannel reactors. Chem. Eng. Sci. 62, 1161–1170 (2007).

Duyar, M. S. et al. Kinetics of CO2 methanation over Ru/Γ-Al2O3 and implications for renewable energy storage applications. J. CO2 Util. 12, 27–33 (2015).

Kresse, G. et al. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Perdew, J. P. et al. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Monkhorst, H. J. et al. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188–5192 (1976).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2017M3D1A1040692) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology and the Saudi Aramco-KAIST CO2 Management Center.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.K. and H.L. developed the project. C.K., J.L., W.D.K., and D.C.L. carried out the experimental work. S.H. and J.K. performed theoretical calculation. All authors wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, C., Hyeon, S., Lee, J. et al. Energy-efficient CO2 hydrogenation with fast response using photoexcitation of CO2 adsorbed on metal catalysts. Nat Commun 9, 3027 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-05542-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-05542-5

This article is cited by

-

Solar-driven photothermal catalytic CO2 conversion: a review

Rare Metals (2024)

-

Advances of photothermal chemistry in photocatalysis, thermocatalysis, and synergetic photothermocatalysis for solar-to-fuel generation

Nano Research (2022)

-

Scope for Spherical Bi2WO6 Quazi-Perovskites in the Artificial Photosynthesis Reaction—The Effects of Surface Modification with Amine Groups

Catalysis Letters (2021)

-

How Rh surface breaks CO2 molecules under ambient pressure

Nature Communications (2020)

-

Heterogeneous catalysts for catalytic CO2 conversion into value-added chemicals

BMC Chemical Engineering (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.