Abstract

Topological quantum states of matter, characterized by geometrical features of electronic band structures, have been extensively studied. Among them, the topological electronic state with magnetic order remains elusive because of a scarce number of examples. Here we present experimental observations proving that the pyrochlore iridate, when electronically tuned, can be a topological Weyl semimetal as predicted by recent theories. We observe a sizable spontaneous Hall conductivity with minimal magnetization only within a few Kelvin below the all-in all-out magnetic ordering temperature. Our theoretical calculation, which is quantitatively consistent with the observation, suggests that the presence of linearly-dispersing crossing points (Weyl points), acting as a source/sink of a quantized magnetic flux, potentially gives rise to such an enormous effect. The manifestation of the salient Hall response provides one important example of topological states, which promotes a better understanding of Weyl semimetal and indicates the new research direction for the topological-materials design.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Origins of anomalous Hall effect (AHE), conventionally produced by the presence of the magnetization, have been a longstanding issue in condensed matter physics since its discovery more than a century ago1. An intrinsic mechanism of AHE was first proposed by Karplus and Luttinger who attributed it to the electronic band structure with spin–orbit interaction2, which generates an additional contribution in a Hall current with no energy consumption. Recently, this mechanism has been reformulated in terms of the Berry curvature, i.e., the quantum geometric/topological property of the Bloch wave functions3. Since the concept of the topological nature was appreciated, the intrinsic mechanism has received a renewed interest from a broader perspective over the past few decades; the Berry phase is now considered as the key concept for AHE, successfully explaining AHEs observed in a number of magnetic materials4,5,6,7,8,9. Recently, Weyl semimetal (WSM) has drawn much attention as a unique class of materials that potentially shows an enormous Hall response10,11. WSM is the semimetal or zero-gap semiconductor in which the two non-degenerate bands cross linearly at the band-touching points, i.e., Weyl points (WPs)10,11,12,13. Intriguingly, WP can be regarded as a magnetic monopole of Berry curvature in k-space, and therefore, its position is expected to be manifested in AHE.

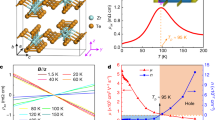

A family of pyrochlore iridates R2Ir2O7 is the first existing compound that is proposed to realize a magnetic WSM by a first-principle calculation10. The pyrochlore iridates host symmetry identical to the diamond lattice (Fig.1a) and are considered to be a fertile ground to potentially produce topologically-nontrivial electronic states14. Furthermore, the magnetic ordering configuration shows the all-in all-out (AIAO, 4/0) state which breaks the time-reversal symmetry without reducing the cubic lattice symmetry (Fig. 1b). These conditions are remarkably suitable for the realization of topological states. The recent angle-resolved photoemission (ARPES) study has revealed that the ground state of the paramagnetic metal R = Pr is a unique semimetal with a quadratic-band-touching point right across the Fermi level, which evolves into abundant topologically-nontrivial phases by symmetry-breaking perturbations15,16. When the time-reversal symmetry is broken by the AIAO magnetic order, for instance, WSM is predicted to emerge with 8 WPs for intermediate electron-correlation strengths12,13. In general, WSM is stable against perturbations as each WP is protected by the topological charge. In fact, the R = Nd compound undergoes the AIAO magnetic order below TN, accompanying a metal-insulator transition (Fig. 1c); the theories10,12,13 predict the AIAO WSM state in the vicinity of the AIAO charge-gapped state. Nonetheless, the experimental confirmation of WSM under zero magnetic field turns out to be challenging because the charge gap appears to open so easily by the pair annihilation of WPs which quickly immigrate as a function of the magnetic order parameter and collide with each other at the zone boundaries, consequently leaving metallic fragments only in magnetic domain walls as remnants of the surface state in the gapped state13,17,18. Therefore, WSM is expected in an extremely narrow temperature region right below TN, still being missed so far19.

Phase diagram and representative magnetic transport properties in R2Ir2O7. a Pyrochlore lattice structure. Orange balls depict Nd ions and green ones are Ir ions. b Schematic magnetic configuration of all-in all-out state for A domain (left) and B domain (right). Phase diagram of (Nd1-xPrx)2Ir2O7 in the plane of c temperature and external pressure, d temperature and magnetic field at 1.8 GPa. According to the previous study22, the chemical substitution of Nd ions with Pr ones effectively scales with the external pressure P, i.e., “chemical pressure”. In Fig. 1c, we apply pressure on R = Nd while the x = 0.5 composition under ambient pressure corresponds to P = 3.3 GPa. PM SM stands for paramagnetic semimetal, 4/0 WSM stands for 4-in 0-out (all-in all-out) Weyl semimetal, AIAO I for all-in all-out insulator, 3/1 WSM for 3-in 1-out Weyl semimetal, respectively. e Magnetic field dependence of Hall conductivity and longitudinal conductivity. f Magnified figures of Fig. 1e in the field range between −4 T and 4 T. Red and blue marks and lines are on field-decreasing process and on field-increasing process, respectively

Here we exploit the electronic transport measurements on pyrochlore Nd2Ir2O7 and (Nd0.5Pr0.5)2Ir2O7 by applying pressure and magnetic field to search for the smoking gun of the predicted WSM state. A salient spontaneous Hall effect accompanied by a vanishingly small magnetization is observed only within the narrow temperature window right below TN. Assuming that the observed Hall effect is provoked by the emergence of WPs which can be regarded as a source or sink of the quantized magnetic flux in k-space, we carry out the numerical analysis of the Hall conductivity. As a result, the minimal tilting of the magnetic moment deviating from the ideal AIAO state is proved to cause such an enormous Hall effect. The qualitative consistency with the experiment indicates that the WSM can be realized in pyrochlore iridates, offering a significant step towards the material design for magnetic topological systems.

Results

Phase diagram for pyrochlore iridates and spontaneous hall effect

To explore the WPs in this system, we take advantage of the Hall effect which is sensitive to the Berry phase3. For this purpose, high-quality single crystals of R = Nd (Nd2Ir2O7) were prepared for transport measurements under fine control of temperature, hydrostatic pressure, and magnetic field. Figure 1d shows the phase diagram as a function of magnetic field for Nd2Ir2O7 (R = Nd) at the pressure P = 1.4 GPa. At zero magnetic field, the magnetic transition occurs at 12 K from paramagnetic to AIAO state. The application of the field along [111] crystalline direction modulates the AIAO pattern by flipping one of four magnetic moments on vertices of a tetrahedron, referred to as 3-in 1-out (3/1) configuration. In accordance, the electronic transport properties change dramatically (Fig. 1e); as the field increases, the longitudinal conductivity σxx rises up, reaches the maximum around 4T, and then decreases down to almost a half of its maximum at 14T. Accordingly, the Hall conductivity σxy also shows nonmonotonous field dependence (Fig. 1e); as the magnetic field increases, σxy increases in a low-field region, reaches the maximum around 7T, and then decreases. According to the ref. 20., the magnetization monotonically increases and saturates the value which is expected for Nd-4f 3-in 1-out state. The observed σxy is different from the conventional AHE which is proportional to magnetization; it presumably reflects the variation of the electronic structures into the other topological state (WSM (3/1)) that can induce the nontrivial contribution to AHE inherent to WPs, as argued in previous reports20,21. Hereafter, we shall take an attentive look into the low-field range in which the AIAO order is preferred. Figure 1f shows the magnified view of the low-field region highlighted in Fig. 1e. The σxx on the field- decreasing process (denoted by the red line) is smaller than that on the field-increasing process (the blue line) in the positive field region, and they turn opposite in the negative field. This hysteresis can be explained by the unique configuration of AIAO order; there are two types of magnetic domains in AIAO state as depicted in Fig. 1b (here we term A and B domain, respectively), each of which can be aligned by the application of the field along [111] or the opposite direction22. The aligned AIAO configuration can induce the odd component of σxx as demonstrated in a previous study23. Therefore, the butterfly-type hysteresis of σxx within ±0 T indicates that the single domain state is realized after applying the magnetic field along [111] direction. Significantly, the hysteresis is also discerned in σxy; as the magnetic field decreases, σxy denoted in red marks decreases towards −1 Ω−1 cm−1 with a sharp dip at 0 T. σxy on the field-increasing process (blue marks) shows the similar field dependency with the opposite sign, shaping an unambiguous diamond-type hysteresis within ±2 T.

To gain more insight into the spontaneous component of σxy, we study the temperature and pressure dependence which allows us to control the magnetic state via tuning of the effective bandwidth. As shown in Fig. 1c, the TN systematically decreases with increasing hydrostatic pressure due to the enhancement of electron hopping interaction. The top figures of Fig. 2 display the field dependence of σxy at several temperatures and pressures. At TN, where the data are denoted by black marks, σxy shows no difference between increasing and decreasing field process. At a lower temperature (denoted in red marks), by contrast, the hysteresis conspicuously shows up with the value of ~±1 Ω−1 cm−1 at 0 T. On further decreasing temperature, the hysteresis loop is abruptly closed and the spontaneous component of σxy becomes almost indiscernible even at a few Kelvin lower than TN (blue marks). Such a characteristic temperature dependency is ubiquitously observed through the pressures of 1.4–2.2 GPa. The bottom figures of Fig. 2 show the field dependence of σxx as an important reference to the AHE state. At TN, the application of the field decreases σxx slightly like a typical magnetoresistance effect. However, the magnetoconductivity turns positive and shows a small hysteresis at lower temperatures. Particularly, in the narrow temperature region where the hysteresis of σxy is remarkably pronounced, the value of σxx ranges from ~700 Ω−1 cm−1 (at P = 1.4 GPa) to ~1000 Ω−1 cm−1 (at P = 2.2 GPa). Correspondingly, σxy increases from ~1.0 Ω−1 cm−1 to ~1.3 Ω−1 cm−1 with increasing pressure as seen in Fig. 2a–c. These obtained values of σxx and σxy reasonably fall onto the intrinsic AHE regime (AHE originating from the Berry phase mechanism)24 in which various families of ferromagnet such as a diluted magnetic semiconductor (Ga,Mn)As25 or a spinel-type chalcogenide CuCr2Se4-xBrx with high critical temperature26 are categorized. With further lowering temperature, the hysteresis of σxy becomes nearly unobservable especially below ~200 Ω−1 cm−1 of σxx, at which the charge gap starts to open19,27.

Magnetotransport properties of Nd2Ir2O7 near the transition temperature at several pressures. Magnetic field dependence of Hall conductivity (a–c) and longitudinal conductivity (d–f) for a field along the [111] crystallographic direction at a, d 1.4 GPa, b, e 1.8 GPa, c, f 2.2 GPa, respectively. The open (colored) marks are Hall conductivities on increasing (decreasing) field process which is indicated by black arrows

There are three main mechanisms of AHE which are widely accepted nowadays; the skew-scattering, the side-jump, and the intrinsic contribution3. The former two are attributed to a carrier scattering by crystalline disorders or impurities, and the last one is driven by Berry phase of a Bloch wave function. On the basis of prior experiments and microscopic theories3, it is natural to separate them by the transport lifetime. For this reason, we can safely rule out the skew-scattering contribution which basically is dominant in the high-conductivity regime (σxx≥106 Ω−1 cm−1). The rest mechanisms are the side-jump or the intrinsic; however, it is difficult to partition each other only according to the scaling rule between σxx and σxy. We therefore pay our attention to the temperature dependency. As one can see in Fig. 2, the spontaneous part of σxy increases abruptly right below TN and almost disappears at 1 K lower temperature, during which σxx decreases monotonically and smoothly. Since the side-jump mechanism originates from an impurity scattering, it can hardly explain the observed steep temperature dependence. Thus, we conclude that the intrinsic mechanism, which is sensitive to the electronic band structure, is most plausible for σxy observed in the course of the phase transition.

Magnetization property of (Nd0.5Pr0.5)2Ir2O7

Next, we examine the behavior of magnetization M which is anticipated to correlate with AHE. For the experiment we have grown single crystals of R-amalgamated (Nd0.5Pr0.5)2Ir2O7 (TN = 3.8 K) which are large and qualified enough to measure both M and σxy reliably at ambient pressure without using the pressure cell. From the previous study [21] we note that the present R = Nd0.5Pr0.5 compound corresponds to the R = Nd compound under an effective pressure of P = 3.3 GPa (see Fig.1c). Figure 3a, b show the field dependence of σxy and M at 2 K. σxy exhibits a similar magnetic-field dependency to that for the undoped Nd2Ir2O7 under hydrostatic pressures except for the sharp close of the hysteresis loop at ±0.8 T. A hysteresis of M between field-increasing and field-decreasing process is barely visible in the same field range as well. To investigate the hysteresis behavior more closely, we show the difference of σxy (Δσxy) and M (ΔM) between the two processes in Fig. 3c, d, respectively. One can clearly see that both Δσxy and ΔM exhibit significant field dependencies at 2 K (<TN) whereas they are almost zero at 4 K (>TN). Especially, the field dependency of Δσxy is complex; starting from −0.5 Ω−1 cm−1 at 0 T, it decreases down to −0.8 Ω−1 cm−1 at ±0.6 T, abruptly jumps towards +0.5 Ω−1 cm−1 at ±0.8 T, and eventually goes to zero above ±1 T. To understand this behavior, we compare it with ΔM. Firstly it simply increases up to ~30 mμB/f.u. with increasing field up to 0.6 T. This can be entirely accounted for in terms of the aligned AIAO single domain state that induces an asymmetric term of M ref. 22. Above 0.6 T, ΔM precipitously drops because of the switching of the magnetic domain. These behaviors are consistently observed in Nd2Ir2O7 as well20. Thus the domain state can be assigned as displayed in the top bars of Fig. 3. One might think that ΔM contains not only the contribution of Ir-5d moments but also that of R-ion 4 f moments. To check the contribution of the Ir-5d moment, we also measured M of Eu2Ir2O7 single crystal with non-magnetic R = Eu (see Supplementary Fig. 1). We have found that the value of the spontaneous M for R = Eu in the AIAO state is comparable with that for R = Nd0.5Pr0.5. It indicates that the Ir-5d moment is responsible for the observed ΔM perhaps because the single-ion anisotropy of R-4f moments is too strong to contribute to the near-zero-field M. On this basis, we conclude that the negative Δσxy below 0.6 T, which appears to be correlated with ΔM, arises from the single-domain state, while the positive Δσxy around 0.8 T corresponds to the domain switching. It is noteworthy that the magnitude of the present Δσxy at 0 T is significantly large despite of the minimal value of ΔM. As mentioned above, the present system locates in the intrinsic Hall mechanism regime of the σxx vs. σxy realation. The representative ferromagnets in this regime such as (Ga,Mn)As or CuCr2Se4-xBrx typically show σxy~1–10 Ω−1 cm−1 and σxx~1000 Ω−1 cm−1, which is nearly the same order of magnitude as that of the present system. However, as compared with the ferromagnetic magnetizations of these compounds, ~5 μB (Ga0.8Mn0.2As) or ~3 μB (CuCr2Se4) per magnetic atom, respectively, the spontaneous magnetization in the present system is astoundingly smaller by three orders of magnitude. It reminds us of the recent studies on the isostructural Pr2Ir2O727 and the Heusler compounds Mn3Z (Z = Sn28 and Ge29) which exhibit large AHE with small magnetization. In the former compound, it is argued that the Pr-4f localized magnetic moment orders the ferromagnetic 2-in 2-out configuration below 0.3 K, inducing a spontaneous AHE via RKKY interaction between Pr-4f moments and Ir-5d itinerant electrons27. The latter compounds28,29 show exceptionally large AHE (σxy~500 Ω−1 cm−1 with M~0.006 μB/Mn) with non-colinear magnetic order. However, they are highly conductive metals with a large carrier number of ~1.9×1022 cm−1. Actually, the recent ARPES reveals that Mn3Sn has the large Fermi surface around M point as well as Weyl points which are ~60 meV above the Fermi energy30. On the other hand, the present compound Nd2Ir2O7 is predicted to host WPs right at the Fermi level10, which may enable us to directly probe an intriguing effect inherent to WPs such as chiral anomaly31.

Hall conductivity and magnetization for (Nd0.5Pr0.5)2Ir2O7. Magnetic field dependence of a Hall conductivity and b magnetization for a magnetic field along [111] direction at 2 K. The blue (red) lines are Hall conductivity and magnetization on field-increasing (field-decreasing) process. The difference of c Hall conductivity and d magnetization between field-increasing and field-decreasing process. The magenta and blue denote 2 K (>TN) and 4 K (<TN), respectively. The top pictures show the domain states in each process. The red bars indicate A domain, blue ones are B domain, and green ones denote the domain flipping regions

Finally we mention the microscopic origin of the spontaneous magnetization in this material. The appearance of such a magnetization is not specific to the R = Nd or (Nd,Pr) compounds close to the WSM or band-touching SM state, but also observed for the AIAO state of the R = Eu compound (Supplementary Fig. 1) and R = Y32,33,34 with the well-defined charge gap35. At the moment, the microscopic origin of this weak ferromagnetism common to the AIAO state of R2Ir2O7 is not clear, but hardly attributable to extrinsic origins, such as residual strain23 (see also Supplementary Note 1). On the basis of the magnetization measurement and a simple model simulation on polycrystals, reference34 suggests that the deviated valence of Ir ion creates non-magnetic defects of Ir3+, possibly inducing the ferromagnetism. However, it is somewhat different from the present case; a relatively small amount of defects in a single crystal, if any, may position randomly and the Hall current as well as the magnetization should be canceled out as a whole. It is more likely that the magnetic moments cant from the perfect AIAO pattern. This is consistent with the previous studies such as x-ray experiment revealing the q = 0 magnetic vector36. As shown in the following, the obtained values of both M and σxy are reproduced by our calculation which assumes the moment canting.

Theoretical calculation of anomalous hall conductivity in weyl semimetal phase

One plausible origin of the observed AHE with vanishingly small M is a Berry curvature in the electronic band characteristic of the WSM state. On this assumption, we theoretically evaluate the magnitude of σxy. We mimic the effect of magnetic moment on the Ir sites by an effective Zeeman field; the Hamiltonian has the form:

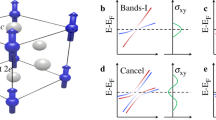

Here, HIr is the single-particle Hamiltonian for the iridium Jeff = 1/2 electrons, mi is the effective Zeeman field at the i-th site, and σi is the vector of Pauli matrices (see Methods). When |mi| = 0, a quadratic band touching exists at the Γ point12,15, which was recently confirmed experimentally16. When mi is in the AIAO configuration, an infinitesimal |mi| splits the quadratic band touching into four pairs of WPs, each located along the eight 111 directions as shown in Fig. 4a. With further increasing |mi|, the WPs move away from the Γ point and eventually vanish by the pair annihilation at the L point on the zone boundary.

Theoretical description of Hall effect. a Schematic picture of the Brillouin zone and the Weyl points in the AIAO phase. The green arrows show the vector connecting the two Weyl points related by the spatial-inversion symmetry. The schematic figure of the band structure of the Weyl points is shown in b along the crystal momentum k along (111) direction. c The position of the Weyl points in the canted AIAO phase. The canted spin configuration is shown in d, and the Hall conductivity in the unit of \(\sqrt 3 e^2/ha\) (a being the lattice constant) as a function of the canting angle θ is in e

An interesting aspect of the WSM is that σxy sensitively reflects the position of the WPs as illustrated in Fig. 4b. Due to the property of WPs, the Chern number defined on each kz plane \({\mathrm{C}}\left( {k_z} \right) = \frac{1}{{2\pi }}{\int} {\mathrm{d}{\it{k}}_x\mathrm{d}{\it{k}}_y{\it{b}}_z\left( {\mathbf{k}} \right)}\) changes by ±1 (bz(k) is the z component of the vector between a pair of WPs b(k)); in Fig. 4b, we illustrate an example where C(kz) = 0 outside the cone and C(kz) = e2/h inside. As σxy is proportional to the integral of C(kz) over kz, σxy increases when the distance between the two nodes increase and vice versa. In the case of pyrochlore iridates with the perfect AIAO order, the integral over C(kz) cancels out, resulting in zero σxy. However, we find that the displacement of the WPs (Fig. 4c) associated with the canting of the spins (Fig. 4d) violates the cancellation.

In Fig. 4e, we show the result of σxy calculated using the Hamiltonian in Eq. (1) for three different HIr and fixed |mi| = 0.04 (Methods). To simulate the small M observed in the experiment, we cant the four moments toward the z axis as shown in Fig. 4d; the abscissa of Fig. 4e is the canting angle θ. This results in the shift of the WPs as schematically shown in Fig.4c and hence violates the cancellation of σxy As the consequence, σxy increases linearly with respect to the canting, and the canting of θ~10−2 rad gives the σxy value of 10−2 of the quantized value, \(\sqrt 3 e^2/ha\) (a being the lattice constant). As the WSM phase of iridates is close to the boundary of MIT, the net moment induced by the canting of θ~10−2 rad is estimated about 10−3μB/Ir (Methods). The calculated values of both σxy and M are consistent with the present experimental observations. These results imply the AHE in Nd2Ir2O7 as well as (Nd1-xPrx)2Ir2O7, proximity to the magnetic phase boundaries, are likely to be a consequence of the Berry phase. Conversely, such a conspicuous zero-field Hall signal in the nearly antiferromagnetic state provides a compelling experimental evidence that the pyrochlore iridate under tuned conditions represent the WSM without time-reversal symmetry. The present study demonstrates that the topologically non-trivial feature gives rise to a salient Hall current with a minimal magnetization, pushing forward to the potential realization of next-generation dissipation-less devices.

Methods

Single crystal growth

Single crystals of Nd2Ir2O7 and its partially Pr-replaced (Nd1-xPrx)2Ir2O7 were grown by the KF flux method. Firstly, mixtures of rare-earth oxides (Nd2O3 and Pr6O11) and iridate IrO2 were ground, pressed into pellets, and then heated at 1273 K for several days. Secondly, the obtained polycrystalline samples were ground again and mixed with KF flux in a ratio of 1:200. The mixtures are placed in a platinum crucible covered with a lid. The crucible was annealed at 1373 K for 3–5 h, and cooled down to 1123 K at a rate of 2 K/h. Finally, crystals were picked up from the KF residual flux by rinsing it out with distilled water. We obtained black octahedron-shaped single crystals which were characterized by x-ray diffraction.

Transport and magnetization measurements

Transport, magnetization, and specific heat measurements were performed using Physical Property Measurement System (PPMS, Quantum Design). Resistivity and Hall conductivity was measured by a standard four-probe method with the current direction parallel to [110] crystalline direction and the magnetic field along [111] crystallographic direction. The Hall conductivity was deduced by the anti-symmetrization of the raw transverse signals perpendicular to the electric current. The pressure was applied by a piston-cylinder pressure cell for PPMS filled with Daphne 7474 oil as the pressure-transmitting medium. The pressure was determined by measuring the superconducting transition temperature of lead which was installed with samples.

Theoretical analysis and models

An effective tight-binding model for Jeff = 1/2 orbitals of Ir electrons HIr is used for evaluation of the anomalous Hall conductivity4, of which the parameters of the nearest-neighbor hopping integrals follows that of a previous calculation used for Nd2Ir2O737. Several different values for the ratio of nearest-neighbor and second-neighbor hopping integral α is considered, as shown in Fig. 4e. To simulate the effect of AIAO ordering and the small ferromagnetic moments observed in the experiment, a site-dependent Zeeman field is introduced as in Eq. (1). We set the magnitude of the Zeeman field to |mi| = 0.04, which is the parameter the Weyl nodes appear approximately at the center of Γ and L points. The calculation of the Hall conductivity was done using a superlattice of N = 4×1923 sites with periodic boundary condition. The size of the ferromagnetic moment mFM is calculated using the same model, which were \(\frac{{\left| {{\mathbf{m}}_{{\mathrm{FM}}}} \right|}}{{\mu _{{\mathrm{Ir}}}}} = 1.03 \times 10^{ - 3}\), 0.91 × 10−3, and 0.82 × 10−3, respectively for α= 0.02, 0.04, and 0.06, at θ= 0.01 rad. Here, μIr is the size of magnetic moment for the J= 1/2 orbital of Ir4+ ions.

Data availability

The data that support these findings are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

References

Hall, E. H. On the “rotational coefficient” in nickel and cobalt. Philos. Mag. 12, 157 (1881).

Karplus, R. & Luttinger, J. M. Hall effect in ferromagnetics. Phys. Rev. 95, 1154 (1954).

Nagaosa, N., Sinova, J., Onoda, S., MacDonald, A. H. & Ong, N. P. Anomalous Hall effect. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 1539 (2010).

Ye, J. et al. Berry phase theory of the anomalous Hall effect: application to colossal magnetoresistance manganites. Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 3737 (1999).

Shindo, R. & Nagaosa, N. Orbital ferromagnetism and anomalous Hall effect in antiferromagnets on the distorted fcc lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 116801 (2001).

Taguchi, Y., Oohara, Y., Yoshizawa, H., Nagaosa, N. & Tokura, Y. Spin chirality, Berry phase, and anomalous Hall effect in a Frustrated ferromagnet. Science 291, 2573 (2001).

Onoda, M. & Nagaosa, N. Topological nature of anomalous Hall effect in ferromagnets. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 71, 19 (2002).

Fang, Z. et al. The anomalous Hall effect and magnetic monopoles in momentum space. Science 302, 92 (2003).

Yao, Y. et al. First principles calculation of anomalous Hall conductivity in ferromagnetic bcc Fe. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 037204 (2004).

Wan, X., Turner, A. M., Vishwanath, A. & Savrasov, S. Y. Topological semimetal and Fermi-arc surface states in the electronic structure of pyrochlore iridates. Phys. Rev. B 83, 205101 (2011).

Yang., K.-Y., Lu, Y.-M. & Ran, Y. Quantum Hall effects in a Weyl semimetal: possible application in pyrochlore iridates. Phys. Rev. B 84, 075129 (2011).

Witczak-Krempa, W., Go, A. & Kim, Y. B. Pyrochlore electrons under pressure, heat, and field; shedding light on the iridates. Phys. Rev. B 87, 155101 (2013).

Yamaji, Y. & Imada, M. Metallic interface emerging at magnetic domain wall of antiferromagnetic insulator: fate of extinct Weyl electrons. Phys. Rev. X 4, 021035 (2014).

Young, S. M. et al. Dirac semimetal in three dimensions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 140405 (2012).

Moon, E.-G., Xu., C., Kim., Y.-B. & Balents, L. Non-Fermi-liquid and topological states with strong spin-orbit coupling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 206401 (2013).

Kondo, T. et al. Quadratic Fermi node in a 3D strongly correlated semimetal. Nat. Commun. 6, 10042 (2015).

Ueda, K. et al. Anomalous domain-wall conductance in pyrochlore-type Nd2Ir2O7 on the verge of the metal-insulator transition. Phys. Rev. B 89, 075127 (2014).

Ma, E. Y. et al. Mobile metallic domain-walls in an all-in all-out magnetic insulator. Science 350, 538 (2015).

Nakayama, M. et al. Slater to Mott crossover in the metal to insulator transition of Nd2Ir2O7. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 056403 (2016).

Ueda, K. et al. Magnetic field-induced insulator-semimetal transition in a pyrochlore Nd2Ir2O7. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 056402 (2015).

Ueda, K. et al. Magnetic-field induced multiple topological phases in pyrochlore iridates with Mott criticality. Nat. Commun. 8, 15515 (2017).

Arima, T.-h Time-reversal symmetry breaking and consequent physical responses induced by all-in all-out type magnetic order on the pyrochlore lattice. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 82, 013705 (2013).

Fujita, T. C. et al. Odd-parity magnetoresistance in pyrochlore iridate thin films with broken time-reversal symmetry. Sci. Rep. 5, 9711 (2015).

Onoda, S., Sugimoto, N. & Nagaosa, N. Quantum transport theory of anomalous electric, thermoelectric, and thermal Hall effects in ferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 77, 165103 (2008).

Chiba, D., Nishitani, Y., Matsukura, F. & Ohno, H. Properties of Ga1-xMnxAs with high Mn composition (x>0.1). Appl. Phys. Lett. 90, 122503 (2007).

Lee, W.-L., Watauchi, S., Miller, V. L., Cava, R. J. & Ong, N. P. Dissipationless anomalous Hall current in the ferromagnetic spinel CuCr2Se4-xBrx. Science 303, 1647 (2004).

Machida, Y. et al. Unconventional anomalous Hall effect enhanced by a noncoplanar spin texture in the frustrated Kondo lattice Pr2Ir2O7. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 057203 (2007).

Nakatsuji, S., Kiyohara, N. & Higo, T. Large anomalous Hall effect in a non-collinear antiferromagnet at room temperature. Nature 527, 212–215 (2015).

Nayak, A. K. et al. Large anomalous Hall effect driven by a nonvanishing Berry curvature in the noncolinear antiferromagnet Mn3Ge. Sci. Adv. 2, e1501870 (2016).

Kuroda, K. et al. Evidence for magnetic Weyl fermions in a correlated metal. Nat. Mater. 16, 1090 (2017).

Aji, V. Adler-Bell-Jackiw anomaly in Weyl semimetals: application to pyrochlore iridates. Phys. Rev. B 85, 241101(R) (2012).

Shapiro, M. C. et al. Structure and magnetic properties of the pyrochlore iridate Y2Ir2O7. Phys. Rev. B 85, 214434 (2012).

Zhu, W. K., Wang, M., Seradjeh, B., Yang, Fengyuan & Zhang, S. X. Enhanced weak ferromagnetism and conductivity in hole-doped pyrochlore iridate Y2Ir2O7. Phys. Rev. B 90, 054419 (2014).

Yang, W. C. et al. Robust pinning of magnetic moments in pyrochlore iridates. Phys. Rev. B 96, 094437 (2017).

Ueda, K., Fujioka, J. & Tokura, Y. Variation of optical conductivity in the course of band-width controlled metal-insulator transitions in pyrochlore iridates. Phys. Rev. B 93, 245120 (2016).

Sagayama, H. et al. Determination of long-range all-in all-out ordering of Ir4+ moments in a pyrochlore iridate Eu2Ir2O7 by resonant x-ray diffraction. Phys. Rev. B 87, 100403(R) (2013).

Tian, Z. et al. Field-induced quantum metal-insulator transition in the pyrochlore iridate Nd2Ir2O7. Nat. Phys. 12, 134 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science through the Funding Program for World-Leading Innovative R&D on Science and Technology (FIRST Program) on ‘Quantum Science on Strong Correlation’ initiated by the Council for Science and Technology Policy, ImPACT program of Council of Science, Technology, and Innovation (Cabinet office, Government of Japan, 888176), PRESTO, CREST, Japan Science and Technology (Grant No. JPMJCR16F1 and JPMJPR15R5), and by JSPS Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (Grants No. 26103006, No. 24224009, No. 18H04214, and No. 16H00981).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.T. and N.N. conceived and guided the project. K.U. and R.K. performed single crystal growth, transport, and magnetization measurements with help of J.F.; H.I carried out the theoretical calculation of the band structure and the Hall conductivity. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ueda, K., Kaneko, R., Ishizuka, H. et al. Spontaneous Hall effect in the Weyl semimetal candidate of all-in all-out pyrochlore iridate. Nat Commun 9, 3032 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-05530-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-05530-9

This article is cited by

-

Magnetotransport of Sm2Ir2O7 across the pressure-induced quantum-critical phase boundary

npj Quantum Materials (2024)

-

Spontaneous topological Hall effect induced by non-coplanar antiferromagnetic order in intercalated van der Waals materials

Nature Physics (2023)

-

Anomalous Hall antiferromagnets

Nature Reviews Materials (2022)

-

Bulk-Surface Electron Coupling in Weyl Semimetals

Journal of Electronic Materials (2022)

-

The topology of electronic band structures

Nature Materials (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.