Abstract

Boron hydride clusters are an extremely diverse compound class, which are of enormous importance to many areas of chemistry. Despite this, stable aluminium hydride analogues of these species have remained staunchly elusive to synthetic chemists. Here, we report that reductions of an amidinato-aluminium(III) hydride complex with magnesium(I) dimers lead to unprecedented examples of stable aluminium(I) hydride complexes, [(ArNacnac)Mg]2[Al6H6(Fiso)2] (ArNacnac = [HC(MeCNAr)2]−, Ar = C6H2Me3-2,4,6 Mes; C6H3Et2-2,6 Dep or C6H3Me2-2,6 Xyl; Fiso = [HC(NDip)2]−, Dip = C6H3Pri2-2,6), which crystallographic and computational studies show to possess near neutral, octahedral hypercloso-hexaalane, Al6H6, cluster cores. The electronically delocalised skeletal bonding in these species is compared to that in the classical borane, [B6H6]2−. Thus, the chemistry of classical polyhedral boranes is extended to stable aluminium hydride clusters for the first time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The binary hydrides of boron, i.e. boranes (typically [BxHy]z−, x ≤ y, z = 0–2), are of enormous importance to chemistry from both fundamental and applications standpoints. The vast majority of these species are low oxidation state boron cluster compounds, which exhibit an enormous array of structural types1. The understanding of the structures of such clusters required the early development of revolutionary theories on chemical bonding (e.g. Wade–Mingos rules for electron counting)2,3, which ultimately led to boranes finding applications in areas as diverse as synthesis4, rocket fuel technology5 and medical science6.

It is remarkable that aluminium, boron’s neighbour in group 13, does not form any isolable hydride cluster compounds, or indeed many binary hydride compounds at all, e.g. AlH3, H2Al(μ-H)2AlH2 and [AlH4]− 7. With that said, a handful of transient, low oxidation state alane cluster compounds have been studied in the gas phase, and some, e.g. Al4H6, have been shown to have fleeting stability8,9,10,11. Given that numerous ligand substituted, metalloid aluminium cluster compounds, e.g. [Al77{N(SiMe3)}20]2−, have been reported to be stable at, or close to, room temperature12,13, it seemed that related low-valent aluminium hydride clusters might be ultimately accessible under the right preparative conditions. As a prelude to realising this goal, we have synthesised the first stable binary low oxidation state aluminium hydride fragments, viz. [Al2H6]2− and Lewis base stabilised Al2H4, by reduction of aluminium(III) hydride precursors with magnesium(I) dimers14,15.

Here, we report that related reductions of an amidinato-aluminium(III) hydride complex lead to unprecedented examples of stable aluminium(I) hydride complexes, [(ArNacnac)Mg]2[Al6H6(Fiso)2] (ArNacnac = [HC(MeCNAr)2]−, Ar = C6H2Me3-2,4,6 Mes; C6H3Et2-2,6 Dep or C6H3Me2-2,6 Xyl; Fiso = [HC(NDip)2]−, Dip = C6H3Pri2-2,6), which possess near neutral hypercloso-hexaalane, Al6H6, cluster cores. Thus, this work represents a unique extension of the chemistry of classical polyhedral boranes to that of their alane analogues.

Results

Synthetic and spectroscopic studies

Treatment of benzene, toluene, cyclohexane or hexane solutions of the formamidinato-aluminium(III) hydride complex, [{(μ-N,N-Fiso)Al(H)(μ-H)}2]16, with 1.2–2.0 equivalents of β-diketiminato ligated magnesium(I) dimers, [{(ArNacnac)Mg}2] (Ar = Mes, Dep or Xyl)17,18,19 (see Supplementary Materials and Supplementary Figs. 1–5), at elevated temperatures (typically 60–80 °C) reproducibly afforded low yields (ca. 5–20%) of the deep red crystalline aluminium(I) hydride cluster compounds 1 (Fig. 1), upon cooling the reaction solutions to ambient temperature. On several occasions, a number of low yielding colourless crystalline by-products were isolated from the reaction mixtures, including [(Fiso)Mg(DepNacnac)], [(Fiso)2AlH]16, [{(MesNacnac)Mg(μ-H)}2]15 and the dialanate salt, [{(MesNacnac)Mg}2(μ-H)]2[H3Al–AlH3]14 (see Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Figs. 6–9). The nature of these by-products suggests that the reductive mechanism for the formation of 1 could involve several intermediates and/or could compete with side reactions. In order to assess these possibilities, reactions that gave 1 at 70 °C were followed by 1H NMR spectroscopy. This revealed complex mixtures of products after several minutes heating, of which [(Fiso)Mg(Nacnac)] was identified in significant quantities (Supplementary Fig. 10). Definitive identification of products, other than those which were later isolated as crystalline solids, was not possible, and the mechanism of formation of 1 is not certain at this time.

To the best of our knowledge compounds 1 represent the first examples of isolated aluminium(I) hydride complexes, though mononuclear examples have recently been tentatively proposed as unstable intermediates in solution-based reactions20. The cluster compounds have negligible solubility in common deuterated solvents once crystallised, so no meaningful solution state spectroscopic data could be acquired for them. The most relevant solid state spectroscopic data (Supplementary Figs. 11, 12) for the compounds come from their infrared spectra, which exhibit single bands in the characteristic region for terminal Al–H stretching modes7 (e.g. 1a: ν = 1798 cm−1). In addition, stronger bands are seen at lower wavenumber (e.g. 1a: ν = 1648 cm−1) that possibly arise from a weakly bridging Al–H···Mg stretching mode, though these bands overlap with ligand stretching absorptions (see below). Noteworthy is the fact that the band at ν = 1798 cm−1 observed for 1a is completely absent in the infrared spectrum of its hexa-deuteride analogue, 1a-D, which was prepared by magnesium(I) reduction of [{(μ-N,N-Fiso)Al(D)(μ-D)}2]. The Al-D stretching band for 1a-D should occur at ca. 1270 cm−1, but this is likely masked by strong ligand stretching modes in that region (Supplementary Fig. 12).

Crystallographic studies

All complexes 1 were crystallographically characterised and found to be isostructural, so only the molecular structure of 1a is depicted in Fig. 2 (see Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Figures 13 and 14). The hydride ligands of each cluster were located from difference maps and freely refined. A neutron diffraction study was also carried out on compound 1a, which unambiguously confirmed the presence and connectivity of the six hydride ligands, and the absence of any other terminal, bridging or interstitial hydrides within the cluster core (see Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Figs. 15, 16). The compounds can be considered as having near neutral, distorted octahedral Al6H6 cores, opposing equatorial sides of which are coordinated by bridging, electronically delocalised formamidinate ligands. The remaining equatorial sides of the octahedron are bridged by [(MesNacnac)Mg]+ cations, which have weak interactions with the two hydride ligands that project from each side. Terminal hydride ligands coordinate to the apical aluminium centres of the cluster core, though these are slightly offset from the vector passing through the two aluminium centres to which they are coordinated, presumably for steric reasons. All of the Al–Al distances within the Al6 core lie in the known range for such bonds (mean: 2.72(12) Å, search of the Cambridge Crystallographic Database, February 2018), though the equatorial Al–Al distances (2.701(2) Å and 2.826(2) Å) are significantly longer than those between all axial and equatorial aluminium centres (2.631(2)–2.691(2) Å). The shorter of the equatorial Al–Al interactions are, not surprisingly, those which are bridged by the formamidinate ligands.

Molecular structure of 1a. Hydrogen atoms, except hydrides, omitted. Ellipsoids shown at the 20% probability level, except aryl substituents, which are shown as wire frame. Selected bond lengths (Å): Al(1)–Al(2) 2.6317(15), Al(1)–Al(3) 2.6340(17), Al(1)–Al(2)′ 2.6472(15), Al(1)–Al(3)′ 2.6907(18), Al(2)–Al(3) 2.701(2), Al(2)–Al(3)′ 2.8257(14), Al(3)–N(2) 1.950(3), Al(2)–N(1) 1.925(3), Al(1)–H(1) 1.52(3), Al(2)–H(2) 1.55(3), Al(3)–H(3) 1.57(3), Mg(1)–H(2) 1.96(3), Mg(1)–H(3)′ 1.98(3). Symmetry operation: −x + 2, −y + 1, −z

Electronic structure and computational studies

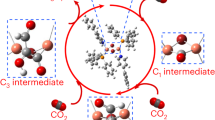

The neutral distorted, octahedral Al6H6 cluster cores of 1 somewhat resemble the structure of the classical polyhedral borane, closo-[B6H6]2− 1, despite their aforementioned elongated equatorial Al–Al interactions. This is intriguing as Al6H6 can be viewed as having 12 (i.e. 2n) valence electrons (i.e. 2 from each Al vertex) contributing to the skeletal Al–Al bonding of the cluster core. As such, it would be expected to have a more unsymmetrical, capped structure than the 14 skeletal valence electron (2n + 2) closo-[B6H6]2−, according to Wade–Mingos rules2,3. Indeed, computational studies have predicted a number of more open and unsymmetrical structures for Al6H621,22, which are close in energy. Of course, in 1 the distorted octahedral geometry of this fragment is likely enforced by coordination to the amidinate ligands, which computational studies suggest do not add to the skeletal electron count (see below). For sake of comparison, isoelectronic B6H6 and Ga6H6, which have not been isolated experimentally, have been predicted to have capped trigonal bipyramidal hypercloso-structures, with all hydrides terminal23,24. Also worthy of mention are several ligand substituted analogues of Al6H6, e.g. B6(NMe2)625 and Ga6{SiMe(SiMe3)2}624, which possess distorted octahedral structures with several elongated E–E bonds, not dissimilar to the situation in 1. In the case of Ga6{SiMe(SiMe3)2}6, calculations on the model compound Ga6H6 suggest that this can be attributed to a Jahn–Teller distortion arising from loss of degeneracy of the t2g HOMOs of closo-[Ga6H6]2− upon removal of two electrons from that dianion24.

In order to shed light on the nature of the bonding in the Al6H6 core of 1, DFT calculations (theory level: RI-BP86/def2-TZVPP) were carried out on a cut-down model of the cluster compounds, viz. [(MeNacnac)Mg]2[Al6H6(HFiso)2] 1′ (MeNacnac = [HC(MeCNMe)2]−, HFiso = [HC(NH)2]−) (Supplementary Methods). The geometry of the complex (Supplementary Fig. 7 and Supplementary Table 2) optimised to be similar to those of 1, including a distorted octahedral Al6H6 core with somewhat shorter Alax–Aleq bonds (2.650–2.668 Å) than Aleq–Aleq distances (2.718–2.819 Å). Reassuringly, the calculated infrared spectrum of 1′ (Supplementary Table 3) exhibits terminal and bridging Al–H stretching bands (ν = 1797 cm−1 (m) and 1649 cm−1 (s) respectively) that are very close to the experimental values for 1a, thus supporting the use of 1′ as a model for 1. The charges on the whole Al6H6 fragment (−0.67), both HFiso ligands (−1.10) and both (MeNacnac)Mg fragments (+1.76) (Supplementary Table 4), indicate that 1′ is best viewed as an anion coordinated, near neutral hypercloso-Al6H6 cluster, having weak hydride bridges to [(MeNacnac)Mg]+ cationic units. The calculated Wiberg bond indices (WBI) for the Alax–Aleq bonds (0.63–0.66) (Supplementary Table 5) are suggestive of relatively strong bonding interactions, while the WBIs for the Aleq-Aleq interactions are much smaller (0.23–0.31). In line with this result is the fact that no bond critical points were found between the equatorial aluminium centres (Supplementary Fig. 8). Calculations on the [Al6H6(HFiso)2]2− dianion, in the absence of the [(MeNacnac)Mg]+ cations, showed this fragment to be stable, with a geometry similar to that in the full contact ion compound (Supplementary Fig. 17 and Supplementary Table 2). This, combined with the fact that the uncoordinated Al6H6 octahedral unit was calculated to be an unstable entity in the electronic singlet state, confirms that the hypercloso-Al6H6 moiety of 1′ is stabilised by coordination to the HFiso anions.

The electronic structure of the [Al6H6(HFiso)2]2− dianion was calculated and found to be similar to that of the full contact ion compound (Supplementary Figs. 19–21), so only the former is displayed in Fig. 3. There are seven Al-based molecular orbitals (MOs) on the dianion, six of which are filled, in line with the view that the cluster is a 12 skeletal valence electron species. None of these MOs are degenerate, but they do closely resemble the seven filled cluster based MOs for closo-[B6H6]2− (triply degenerate t2g and t1u orbital sets, and a1g orbital)2, and thus display significant electronic delocalisation over the Al6 core. The lack of degeneracy of the Al-based MOs of [Al6H6(HFiso)2]2− arises from the lower symmetry, and lower skeletal electron count, of the dianion relative to those of closo-[B6H6]2−. Interestingly, the LUMO+7 (lower energy empty MOs are ligand based) of [Al6H6(HFiso)2]2− resembles the degenerate t2g HOMO of closo-[B6H6]2− which exhibits the most analogous, quasi-equatorial B–B bonding character. This goes a long way to explaining the weak Aleq–Aleq interactions in 1′. The HOMO and HOMO-1 of [Al6H6(HFiso)2]2− are reminiscent of the other two t2g orbitals of closo-[B6H6]2−, while the HOMO-2, HOMO-3 and HOMO-4 show similarities with the t1u orbitals of the borane. At lower energy is the HOMO-9 which corresponds to the a1g orbital of closo-[B6H6]2−. No Al-based MO exhibits significant contributions from the HFiso anions, the lone pairs of which are polarised towards their N-centres, and should therefore not be included in the counting of electrons contributing to Al–Al bonding within the cluster core. This view is supported by results of an energy decomposition analysis of the intrinsic interactions between the Al6H6 core and the amidinate ligands in [Al6H6(HFiso)2]2− (Supplementary Fig. 22 and Supplementary Table 6). Calculations of the NICS values of 1′ at the centre of the Al6H6 core suggest that the cluster exhibits significant 3-dimensional aromaticity (NICSiso = −12.49 ppm, NICSzz = −45.74 ppm) (Supplementary Table 7), as is common for polyhedral boranes1.

Methods

General

Experiments were carried out under a dry, oxygen-free dinitrogen atmosphere using Schlenk-line and glove-box techniques. All solvents and reagents were rigorously dried and deoxygenated before use. Compounds were variously characterised by elemental analyses, NMR, FTIR, and Raman spectroscopies, single crystal X-ray diffraction studies, and DFT calculations. Further details are available in Supplementary Methods.

Preparation of [(XylNacnac)MgI(OEt2)]

A freshly prepared solution of MeMgI (28.4 mmol) in diethyl ether (80 mL) was added over 20 min to a stirred solution of XylNacnacH26 (8.08 g, 26.4 mmol) in diethyl ether (100 mL) at −20°C, yielding a colourless precipitate. The suspension was warmed to room temperature and stirred for 1 h after which time the precipitate of the title compound was collected by filtration. The supernatant solution was concentrated to ca. 40 mL and cooled to −30 °C to afford a second crop (12.86 g, 90%). M.P. 195–197 °C (decomp.); 1H NMR (400 MHz, 298 K, C6D6) δ = 0.44 (br, 6H; OCH2CH3), 1.54 (s, 6H; NCCH3), 2.07 (br, 6H; ortho-CH3), 2.64 (br, 6H; ortho-CH3), 3.11 (br, 4H; OCH2CH3), 4.86 (s, 1H; CH), 6.75–7.15 (m, 6H; Ar-H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, 298 K, C6D6) δ = 13.0 (NCCH3), 18.7 (ortho-CH3), 21.1 (ortho-CH3), 23.4 (OCH2CH3), 65.9 (OCH2CH3), 95.3 (CH), 124.7, 129.6, 131.5, 147.7 (Ar-C), 168.8 (NCCH3); MS (EI 70 eV), m/z (%): 457.1 (MH+-OEt2, 5), 306.4 (XylNacnacH+, 100); IR (Nujol) ν (cm−1): 1518s, 1262m, 1215w, 1197m,1185m, 1148m, 1092m, 1021m, 996m, 857m, 848w, 775s, 758m, 636m. Note: A satisfactory reproducible microanalysis of the compound could not be obtained due to co-crystallisation of the product with small amounts (ca. 3%) of the β-diketimine, XylNacnacH, which could not be removed after several recrystallisations.

Preparation of [{(XylNacnac)Mg}2]

Toluene (80 mL) and diethyl ether (ca. 2 mL) were added to [(XylNacnac)MgI(OEt2)] (1.58 g, 2.40 mmol). The resultant solution was rapidly stirred over a sodium mirror (0.70 g, 30.4 mmol) for 5 days to yield a yellow/green suspension. This was filtered, the yellow filtrate concentrated to ca. 20 mL and placed at −30 °C overnight to give yellow crystals of the title compound. A second crop was isolated after further concentration and cooling of the supernatant solution (0.28 g, 29%). M.P. 180–181 °C (decomp.); 1H NMR (400 MHz, 298 K, C6D6) δ = 1.48 (s, 12H; NCCH3), 1.90 (br. s, 24H; ortho-CH3), 4.76 (s, 2H; CH), 6.85–7.10 (m, 12H; Ar-H); 13C{1H} NMR (100 MHz, 298 K, C6D6) δ = 19.2 (NCCH3), 23.1 (ortho-CH3), 95.3 (CH), 124.1, 128.4, 131.8, 148.0 (Ar-C), 166.3 (NCCH3); MS (EI 70 eV), m/z (%): 659.5 (MH+, 10); IR (Nujol) ν (cm−1): 1555s, 1520w, 1278m, 1262m, 1182m, 1094m, 1023m, 809w, 762m. Note: A satisfactory reproducible microanalysis of the compound could not be obtained due to co-crystallisation of the product with small amounts (ca. 5%) of the iodide bridged magnesium(II) dimer, [{(XylNacnac)Mg(μ-I)}2], which could not be removed after several recrystallisations. The constitution of this co-crystallised mixture was confirmed by a poor quality crystal structure determination of [{(XylNacnac)Mg}2], details of which are not reported here due to the low quality of the diffraction data.

Preparation of [(MesNacnac)Mg]2[Al6H6(Fiso)2] (1a)

[{(μ-N,N-Fiso)Al(H)(μ-H)}2]16 (164 mg, 0.21 mmol) was added to a suspension of [{(MesNacnac)Mg}2]27 (300 mg, 0.42 mmol) in benzene (5 mL) in a grease-free Schlenk flask (20 mm diameter). The mixture was heated to 65 °C for 5 min or until a bright red solution formed. Allowing the solution to stand at room temperature for 4 days resulted in the deposition of red crystals of 1a (20 mg, 18% based on aluminium). M.P. > 150 °C (decomp.) 13C{1H} NMR (75.5 MHz, 298 K, solid state) δ = 17.5, 20.6, 25.4, 27.7, 95.1, 123.8, 129.4, 131.5, 142.1, 146.4, 163.4, 167.4; MS (EI 70 eV), m/z (%): 335.5 (MesNacnacH2+, 100), 365.5 (FisoH2+, 38); MALDI-TOF MS m/z: 335.5 (MesNacnacH2+), 357.4 ((MesNacnac)Mg+), 365.5 (FisoH2+), 389.4 ((Fiso)Al–H+); IR (Nujol) ν (cm−1): 1798m (Al–H str.), 1648s (br, incl. Al–H str.), 1542vs, 1197m, 1176m, 1146s, 1097s, 1021s, 854s, 803s, 755s; Raman (solid under N2, 514 nm excitation, cm−1): ν = 3064m, 1352s, 1318m, 522m, 386m. A similar yield of 1a was obtained when the reaction was conducted in cyclohexane (ca. 12 mL). Elemental analysis calculated for C96H134Al6Mg2N8·C6H12: C 72.29%, H 8.68%, N 6.61%; found: C 72.13%, H 8.55%, N 6.54%. Notes: (i) A few crystals of the known magnesium(II) hydride dimer, [{(MesNacnac)Mg(μ-H)}2]15, the known aluminium(III) hydride, [(Fiso)2AlH]16, and the new colourless dialanate salt, [{(MesNacnac)Mg}2(μ-H)]2[H3Al–AlH3], co-crystallised with 1a from the reaction mixture. All were identified by X-ray crystallography (Supplementary Fig. 9). Insufficient amounts of [{(MesNacnac)Mg}2(μ-H)]2[H3Al–AlH3] were obtained to allow spectroscopic characterisation, but it is noteworthy that the 2,6-diethylphenyl substituted analogue of the compound, [{(DepNacnac)Mg}2(μ-H)]2[H3Al–AlH3], has been previously reported and fully characterised14. (ii) Reproducible low yield syntheses of 1a (typically 5–20%) were achieved under a number of reaction conditions. For example, toluene, hexane, cyclohexane or benzene could be used as the reaction solvent, the reaction temperature was varied from ca. 60–80 °C, the reaction stoichiometry was varied from 1.2:1 to 2:1 ([{(MesNacnac)Mg}2]:[{(μ-N,N-Fiso)Al(H)(μ-H)}2]), and the time the reaction mixture was kept at elevated temperature varied from 5 to 25 min. The time required for the reaction depended strongly on the diameter of the reaction flask. (iii) Compound 1a (and 1b-c) have negligible solubility in common deuterated solvents once crystallised, so no meaningful solution state spectroscopic data could be acquired for them. Attempts to dissolve 1a in d8-THF led to decomposition of the compound. (iv) Attempts were made to obtain solution state spectroscopic data on 1a from red reaction solutions before it crystallised from those solutions. NMR spectroscopic data on those solutions showed complex product mixtures (Supplementary Fig. 10), while ESI mass spectroscopic analyses of the reaction solutions showed no ion that could be assigned to 1a or its fragmentation products.

Preparation of [(DepNacnac)Mg]2[Al6H6(Fiso)2] (1b)

[{(μ-N,N-Fiso)Al(H)(μ-H)}2]16 (102 mg, 0.13 mmol) was added to a suspension of [{(DepNacnac)Mg}2]19 (200 mg, 0.26 mmol) in benzene (2 mL) in a grease-free Schlenk flask (20 mm diameter). The mixture was heated to 65 °C for 5 min or until a bright red solution formed. Allowing the solution to stand at room temperature for 4 days resulted in the deposition of deep red crystals of 1b (10 mg, 5% based on aluminium). M.P. > 150 °C (decomp.); IR (Nujol) ν (cm−1): 1834m (Al–H str.), 1633s (br, incl. Al–H str.), 1538s, 1366vs, 1338s, 1320s, 1261s, 1232m, 1177s, 1108s, 1023s, 946m, 802s. No solution state spectroscopic data could be obtained for the compound due to its negligible solubility in common organic solvents. A reproducible microanalysis of the compound could not be obtained due it its low yield and the fact that it co-crystallised with the known dialanate salt, [{(DepNacnac)Mg}2(μ-H)]2[H3Al–AlH3]14, and the new, colourless magnesium(II) complex, [(Fiso)Mg(DepNacnac)]. The latter compound was subsequently intentionally synthesised, spectroscopically characterised, and its X-ray crystal structure obtained (Supplementary Figure 8).

Preparation of [(XylNacnac)Mg]2[Al6H6(Fiso)2] (1c)

[{(μ-N,N-Fiso)Al(H)(μ-H)}2]16 (118 mg, 0.15 mmol) was added to a suspension of [{(XylNacnac)Mg}2] (200 mg, 0.30 mmol) in benzene (3 mL) in a grease-free Schlenk flask (20 mm diameter). The mixture was heated to 65 °C for 5 min or until a bright red solution formed. Allowing the solution to stand at room temperature for 4 days resulted in the deposition of deep red crystals of 1c (10 mg, 4% based on aluminium). M.P. > 150 °C (decomp.); IR (Nujol) ν (cm−1): 1829m (Al–H), 1623m (br incl. Al–H str.), 1593m, 1543vs, 1336s, 1322s, 1265m, 1257m, 1233m, 1185s, 1096m, 1031m, 951m, 934m, 843m, 802m, 762s, 698m. No solution state spectroscopic data could be obtained for the compound due to its negligible solubility in common organic solvents. A reproducible microanalysis of the compound could not be obtained due it its low yield and the fact that it co-crystallised with colourless crystalline compounds from which it could not be completely separated.

Preparation of [(MesNacnac)Mg]2[Al6D6(Fiso)2] (1a-D)

[{(μ-N,N-Fiso)Al(D)(μ-D)}2] (165 mg, 0.21 mmol), prepared as per the procedure for [{(μ-N,N-Fiso)Al(H)(μ-H)}2]16 (see Supplementary Methods), was added to a suspension of [{(MesNacnac)Mg}2]27 (300 mg, 0.42 mmol) in benzene (5 mL) in a grease-free Schlenk flask (20 mm diameter). The mixture was heated to 65 °C for 5 min or until a bright red solution formed. Allowing the solution to stand at room temperature for 4 days resulted in the deposition of red crystals of 1a (21 mg, 19% based on aluminium). M.P. > 150 °C (decomp.); IR (Nujol) ν (cm−1): 1665m, 1546s, 1388vs, 1366vs, 1338s, 1259s, 1231m, 1195m, 1146s, 1098s, 1022s, 856m, 803m, 754s, 698s; Raman (solid under N2, 514 nm excitation, cm−1): ν = 1353s, 1320m, 523w, 445m, 380w.

Preparation of [(Fiso)Mg(DepNacnac)]

This compound was a by-product in the preparation of 1b. It was subsequently intentionally synthesised as follows. Toluene (10 mL) was added to a solid mixture of [{(DepNacnac)Mg(μ-nBu)}2]19 (0.390 g, 0.440 mmol) and FisoH (0.331 g, 0.907 mmol) at room temperature. The mixture was then stirred for 90 min at 40 °C to afford a colourless solution. The resultant solution was concentrated under reduced pressure to 3 mL, n-hexane (4 mL) was added, and the solution was stored at −30 °C overnight to afford colourless crystals of [(Fiso)Mg(DepNacnac)] (0.31 g, 47%). M.P.: gradually softens above 210 °C and takes on a yellow colour above 290 °C; 1H NMR (300 MHz, C6D6, 303 K): δ = 1.06 (d, 3JH,H = 6.9 Hz, 24H; CH(CH3)2), 1.10 (t, 3JH,H = 7.6 Hz, 12H; CH2CH3), 1.53 (s, 6H; NCCH3), 2.55 (dq, 2,3JH,H = 15.0 Hz, 7.5 Hz, 4H; CH2CH3), 2.67 (dq, 2,3JH,H = 15.0 Hz, 7.5 Hz, 4H; CH2CH3), 2.99 (sept, 3JH,H = 6.9 Hz, 4H; CH(CH3)2), 4.92 (s, 1H; CH), 6.96–7.10 (m, 12H; Ar-H), 7.94 (s, 1H; N2CH); 13C{1H} NMR (75.5 MHz, C6D6, 303 K): δ = 13.8 (CH2CH3), 23.8 (NCCH3), 24.6 (CH2CH3), 25.0 (CH(CH3)2), 28.7 (CH(CH3)2), 96.0 (CH), 123.6, 123.9, 125.3, 125.9, 137.2, 142.5, 143.8, 147.4 (Ar-C), 169.9 (NCCH3), 171.5 (N2CH); IR (Nujol): ν (cm−1) = 1665m, 1595w, 1537s, 1531s, 1505m, 1462s, 1443s, 1390s, 1377s, 1321m, 1274s, 1266s, 1207m, 1181m, 1108m, 1031m, 1018m, 962w, 934m, 854m, 806m, 799m, 755s, 722m; elemental analysis calculated for C50H68N4Mg: C 80.13%, H 9.14%, N 7.48%; found: C 80.03%, H 9.17, N 7.43%.

Data availability

The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers 1830325–1830331. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

References

Nöth, H. in Molecular Clusters of the Main Group Elements (eds Driess, M. & Nöth, H.) 34–94 (Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2004).

Wade, K. Structural and bonding patterns in cluster chemistry. Adv. Inorg. Chem. Radiochem. 18, 1–66 (1976).

Mingos, D. M. P. Polyhedral skeletal electron pair approach. Acc. Chem. Res. 17, 311–319 (1984).

Brown, H. C. Boranes in Organic Chemistry. (Cornell, Ithaca, 1972).

Martin, D. R. The development of borane fuels. J. Chem. Educ. 36, 208–214 (1959).

Gabel, D. & Endo, Y. in Molecular Clusters of the Main Group Elements (eds Driess, M. & Nöth, H.) 95–125 (Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2004).

Aldridge, S. & Downs, A. J. Hydrides of the main-group metals: new variations on an old theme. Chem. Rev. 101, 3305–3365 (2001).

Li, X. et al. Unexpected stability of Al4H6: a borane analog? Science 315, 356–358 (2007).

Grubisic, A. et al. Closo-alanes (Al4H4, AlnHn+2, 4 ≤n ≤8): a new chapter in aluminum hydride chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 5969–5975 (2007).

Zhang, X. et al. Low oxidation state aluminum-containing cluster anions: LAlH− and LAln − (n = 2–4, L = N[Si(Me)3]2). Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 19, 15541–15548 (2017).

Wang, H. et al. Photoelectron spectroscopy of boron aluminum hydride cluster anions. J. Chem. Phys. 140, 164317 (2014).

Schnöckel, H. Structure and properties of metalloid Al and Ga clusters open our eyes to the diversity and complexity of fundamental chemical and physical processes during formation and dissolution of metals. Chem. Rev. 110, 4125–4163 (2010).

Ecker, A. & Schnöckel, H. Synthesis and structural characterization of an Al77 cluster. Nature 387, 379–381 (1997).

Bonyhady, S. J., Holzmann, N., Frenking, G., Stasch, A. & Jones, C. Synthesis, characterization, and computational analysis of the dialanate dianion, [H3Al–AlH3]2−: a valence isoelectronic analogue of ethane. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 8527–8531 (2017).

Bonyhady, S. J. et al. Synthesis of a stable adduct of dialane(4) (Al2H4) via hydrogenation of a magnesium(I) dimer. Nat. Chem. 2, 865–869 (2010).

Cole, M. L., Jones, C., Junk, P. C., Kloth, M. & Stasch, A. Synthesis and characterization of thermally robust amidinato group 13 hydride complexes. Chem. Eur. J. 11, 4482–4491 (2005).

Jones, C. Dimeric magnesium(I) β-diketiminates: a new class of quasi-universal reducing agent. Nat. Rev. Chem. 1, 0059 (2017).

Stasch, A. & Jones, C. Stable dimeric magnesium(I) compounds: from chemical landmarks to versatile reagents. Dalton Trans. 40, 5659–5672 (2011).

Lalrempuia, R. et al. Activation of CO by hydrogenated magnesium(I) dimers: sterically controlled formation of ethanediolate and cyclopropanetriolate complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 8944–8947 (2015).

Tan, G., Szilvási, T., Inoue, S., Blom, B. & Driess, M. An elusive hydridoaluminum(I) complex for facile C–H and C–O bond activation of ethers and access to its isolable hydridogallium(I) analogue: syntheses, structures, and theoretical studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 9732–9742 (2014).

Marchal, R. et al. Structures and stabilities of small, ligated AlnLn 0/2− and AlnLn+2 clusters (L=H, Cl)—a theoretical study. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 4856–4866 (2012).

Yao, C. H. et al. Structures and electronic properties of hydrogenated aluminum clusters. Eur. Phys. J. D 57, 197–205 (2010).

McKee, M. L., Wang, Z.-X. & von Rague Schleyer, R. Ab initio study of hypercloso boron hydrides BnHn and BnHn −. Exceptional stability of neutral B13H13. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 4781–4793 (2000).

Linti, G., Coban, S. & Dutta, D. Das Hexagallan [Ga6{SiMe(SiMe3)2}6] und das closo-hexagallanat [Ga6{Si(CMe3)3}4(CH2C6H5)2]2−—Der Übergang zu einem ungewöhnlichen precloso-cluster. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 630, 319–323 (2004).

Mesbah, W. et al. Hypercloso-hexa(amino)hexaboranes: structurally related to known hypercloso-dodecaboranes, metastable with regard to their classical cycloisomers. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 5577–5582 (2009).

Feldman, J. et al. Electrophilic metal precursors and a β-diimine ligand for nickel(II)- and palladium(II)-catalyzed ethylene polymerization. Organometallics 16, 1514–1516 (1997).

Bonyhady, S. J. et al. β‐Diketiminate‐stabilized magnesium(I) dimers and magnesium(II) hydride complexes: synthesis, characterization, adduct formation, and reactivity studies. Chem. Eur. J. 16, 938–955 (2010).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Australian Research Council (C.J. and A.S.), the U.S. Air Force Asian Office of Aerospace Research and Development (grant FA2386-18-1-0125 to C.J.), Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (FR 641/25-2) (G.F.), and Director, Bragg Institute, ANSTO, 2011 approval of DB 1959 (A.J.E. and C.J.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.J. and A.S. contributed to conception and design of experiments, data collection, analysis and interpretation; G.F.,A.J.E., S.J.B, D.C. and N.H. contributed to data collection, analysis and interpretation; R.O.P. extracted the neutron single-crystal data from the Laue diffraction images; C.J. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bonyhady, S.J., Collis, D., Holzmann, N. et al. Anion stabilised hypercloso-hexaalane Al6H6. Nat Commun 9, 3079 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-05504-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-05504-x

This article is cited by

-

Open questions in low oxidation state group 2 chemistry

Communications Chemistry (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.