Abstract

Dynamical coupling with high-quality factor resonators is essential in a wide variety of hybrid quantum systems such as circuit quantum electrodynamics and opto/electromechanical systems. Nuclear spins in solids have a long relaxation time and thus have the potential to be implemented into quantum memories and sensors. However, state manipulation of nuclear spins requires high-magnetic fields, which is incompatible with state-of-the-art quantum hybrid systems based on superconducting microwave resonators. Here we investigate an electromechanical resonator whose electrically tunable phonon state imparts a dynamically oscillating strain field to the nuclear spin ensemble located within it. As a consequence of the dynamical strain, we observe both nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) frequency shifts and NMR sidebands generated by the electromechanical phonons. This prototype system potentially opens up quantum state engineering for nuclear spins, such as coherent coupling between sound and nuclei, and mechanical cooling of solid-state nuclei.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dynamical coupling to a high-quality factor (high-Q) resonator, i.e., an interaction with a rapidly oscillating degree of freedom in a resonator, is essential to implementing a wide variety of quantum hybrid devices. For instance, in circuit quantum electrodynamics (QED), which implements dynamical coupling between a superconducting microwave resonator and an artificial atom; quantum non-demolition measurements of the two-level system via the resonator’s frequency shifts have been developed1,2. On the other hand the parametric coupling between photons and phonons (phonons and phonons) in opto-mechanics3 (in coupled mechanical systems) have been used to measure the position of the mechanical resonator below the standard quantum limit4. The resultant sidebands generated on the photonic (phononic) resonance have also been harnessed for sideband cooling the thermal phonons down to the quantum ground state when pumping the red sideband5,6,7, and to generate an inter-resonator quantum entanglement8,9,10,11,12.

Nuclear spins in solids have long relaxation times because of their weak interaction with the surrounding environment, and thus are expected to be utilized for various applications such as quantum information processing13,14,15 and quantum magnetic sensors16. Consequently incorporating the abovementioned concept of coupling a resonator to nuclear spins has the potential to open another class of manipulation and detection methods for the nuclear spins. The concept of circuit QED has already been implemented with electron spins using a superconducting microwave resonator17,18,19,20. In contrast, a similar approach based on superconducting resonator (necessary for their high-Q) is difficult for nuclear spins, because the nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) used to detect and manipulate their states requires high-magnetic fields of a few Tesla. To address this, a natural alternative would be to couple the nuclei to an electromechanical resonator that is compatible with high-magnetic fields, but despite this promise, an experimental demonstration of such a hybrid system remains unexplored.

In the first step towards such a resonator-based hybrid system with a nuclear spin ensemble, we have developed an electromechanical system that imparts dynamical strain to nuclear spins naturally located within it. In this realization, the nuclear spins interact with the fundamental mode of the resonator at 1.7 MHz via mechanical strain in the quadrupole interaction21,22. The NMR of the local nuclei in the resonator can be selectively detected by resistively detected NMR method using the integer quantum Hall effect through a nano-fabricated transport channel at the clamping point of the resonator15. The quadrupole interaction of nuclear spins in solids is important and has a long history in standard NMR and nuclear acoustic resonance experiments23. We note however that most of the work reported so far has focused on static strain21,22,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37 or weak oscillating strain induced by ultrasound applied to bulk specimens38. In contrast, here we achieve larger strain regime of 10−3 at 1.7 MHz with the aid of a high-Q mechanical resonator that can enhance the mechanical displacement (which induces strain) by a factor of Q. As a consequence of this resonator-enhanced dynamical strain effect, we observe both red and blue sidebands on the NMR which correspond to nuclear spin transitions assisted by the absorption and emission of electromechanical phonons. Moreover, frequency shifts in the NMR are also observed, which scaled with the strain from the mechanical motion thus enabling the nuclear spin states to be mechanically manipulated.

Results

Electromechanical resonator and resistively detected NMR

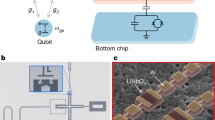

A 50-μm-long doubly clamped electromechanical resonator shown in Fig. 1a was fabricated from a GaAs/AlGaAs heterowafer using sacrificial layer etching (see Methods and Supplementary Fig. 1). Figure 1b details the motional piezovoltage Vd measured at different actuation voltages Va, showing a resonance peak which corresponds to the fundamental flexural mode39,40 with frequency ωM/2π = 1.716 MHz and quality factor Q = 5 × 104. With increasing Va, the mechanical amplitude is deformed into a sawtooth-shape reflecting the emergence of a nonlinearity in the underlying harmonic potential41. This nonlinear feature is further enhanced in the strong driving regime, where the normal and shear strains can become as high as εzz ~ 1 × 10−3 and εxy ~ 2 × 10−3, respectively (see below and Supplementary Note 1).

Experimental setup. a False-color scanning electron microscope image of the device (scale bar, 10 μm). A GaAs-based doubly clamped electromechanical resonator is suspended from the substrate. Two Schottky gate electrodes are defined on the left clamping point in order to piezoelectrically actuate and detect the mechanical motion. b Frequency response of the mechanical resonator with different actuation voltage Va plotted as a function of actuation frequency ωa/2π with ωM/2π = 1.716 MHz. The right axis shows the calibrated mechanical amplitude x1 at the center of the beam. c A schematic of the device structure at the clamping point, where the maximum strain can be induced from the fundamental flexural mode of this resonator. A static magnetic field B0 is applied perpendicular to the 2DEG, while a transverse magnetic field Bx is irradiated to the nuclei underneath the antena gate to which an RF current IRF with a frequency ωRF is also applied. d A plot of ΔIsd (≡Isd − I0 with I0 being the offset current) at B0 = 3.1 T measured as a function of ωRF without mechanical actuation. e A plot of the NMR peak frequency as a function of B0, showing linear B0-dependence, from which a gyromagnetic ratio of 7.3 MHz T−1 for As75 is determined

This GaAs-based resonator hosts three isotopes 75As, 69Ga, and 71Ga, all of which are quadrupole nuclei having spin I = 3/2. Among them 75As has the largest quadrupole moment and the strongest coupling to strain and therefore the effects generated from electromechanical strain are most favorable for this element. The fundamental flexural mode of this resonator creates strain that is magnified at the clamping points (see Supplementary Fig. 2) and thus detection of NMR for the strain-modified nuclei is made at this location. To this end, a resistively detected NMR method is adopted that uses breakdown of the integer quantum Hall effect (see Methods). Figure 1d shows the NMR measured from the 75As nuclei at the clamping point, which is unstrained as the mechanical vibration is not activated and the peak frequency ω0 measured at different external field B0 shows a linear dependence (see Fig. 1e). The corresponding gyromagnetic ratio γ/2π = 7.3 MHz T−1 extracted from a linear fit confirms that the observed peak originates from the NMR of 75As nuclei.

Sideband NMR assisted by electromechanical phonons

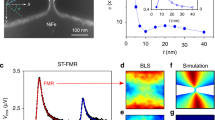

When the electromechanical resonator is driven, it can periodically modulate the quadrupole term associated with the nuclear spins via the motion induced strain. As a consequence of this off-resonant parametric modulation, nuclear spins can form phonon-dressed states, which emerge as sideband NMR peaks as schematically depicted in Fig. 2a. A red (blue) transition can be induced with the absorption (emission) of phonons from (into) the mechanics via the quadrupole interaction and hence the additional NMR peak appears at ω0−(+)ωM. Figure 2b–d (2e) show the observation (simulation) of red and blue sideband NMR peaks for the nuclei under the driven electromechanical oscillation with Va = 40 mV (point 5 in Fig. 3a). The strongest sideband NMR peaks are observed with 75As whilst the weakest with 71Ga, which reflects the magnitude of the quadrupole interaction between the nuclear spins and mechanical strain. We note that the apparently narrower NMR peak of 71Ga is due to the limited signal-to-noise ratio for this nuclear species, which is relatively scarce and has a weaker quadrupole interaction.

NMR sidebands induced by electromechanical phonons. a A red (blue) sideband NMR peak can be induced with the absorption (emission) of an electromechanical phonons. b–d The main and red/blue sideband NMR spectra with relevant isotopes, 75As, 69Ga, and 71Ga from top to bottom, respectively. Each panel shows ΔIsd as function of ωRF with ωR(B) = ω0−(+)ωM, where ω0(75As)/2π = 22.63 MHz, ω0(69Ga)/2π = 31.79 MHz, and ω0(71Ga)/2π = 40.39 MHz at B0 = 3.1 T when the resonator is driven with Va = 40 mV at point 5 in Fig. 3a. The solid lines in the sideband NMR spectra show Gaussian fits of the data. e The simulated NMR spectra for 69Ga using the rotating-wave approximation, which are normalized by the amplitude of the main NMR peak (see Methods)

NMR frequency shift induced by a driven electromechanical strain. a A plot of the mechanical amplitude x1 with stronger actuation: Va = 40 mV. b NMR spectra for 75As nuclei at B0 = 3.1 T under intense mechanical oscillations as a function of ωRF with ω0/2π = 22.606 MHz. From bottom to top, the spectra are measured at (ωa − ωM)/2π = −0.3, 1.0, 6.3, 10.8, and 13.0 kHz with a fixed actuation Va = 40 mV as indicated by the colored open circles in a. c The numerical simulation of the NMR spectra which shows the normalized oscillation amplitude of 〈Iz〉 for x1 = 0, 0.5, 0.75, 0.9, 1.1 μm from bottom to top, respectively. d A plot of the measured NMR peak frequency as a function of x1, where the open square (solid circle) symbol corresponds to the left (center) peak in b determined from the Lorenz fit to the spectra. The error bars correspond to the peak width determined from the fitting. The solid lines show the theoretical frequency shift derived from the numerical simulation

To better understand the observed sideband NMR peaks, the spectra were numerically simulated using a model Hamiltonian that included an oscillating quadrupole interaction associated with the driven mechanical motion:

Here the first term describes the Zeeman effect, \(\hat H_{\mathrm{Z}} = - \hbar \omega _0\hat I_z\), where ω0/2π = γB0 with γ being the gyromagnetic ratio of the relevant nucleus, \(\hat I_z\) is the z-component of the Pauli spin operator \(\hat I\), and ħ the reduced Planck constant. For a nucleus with spin I = 3/2, four spin states \(\left| m \right\rangle\) are Zeeman split to form equally spaced energy levels separated by ħω0. The effect of strain-mediated dynamical coupling from a driven mechanical resonator on nuclear spins is captured by the dynamic quadrupole interaction described by the second term \(\hat H_{\mathrm{Q}}(t) = x(t)\hat J_{\mathrm{Q}}\), which is proportional to the time-dependent mechanical displacement x(t). Here the quadrupole operator \(\hat J_{\mathrm{Q}}\) is

where A1 and A2 are the quadrupole coupling constants at the clamping point and \(\hat I_ +\) and \(\hat I_ -\) are the spin ladder operators (see Supplementary Note 1). The NMR transition triggered by absorbing a photon ωRF irradiated by the antenna gate is described by the third term with \(\hat H_{{\mathrm{RF}}} = - \gamma \hbar B_x\hat I_x\), where \(\hat I_x\) is the x-component of the Pauli spin operator and Bx is the corresponding transverse magnetic field. Equation (1) can simulate the magnetization \(\left\langle {\hat I_z} \right\rangle\) driven by RF irradiation and its amplitude reflects the NMR response of the nuclei under the presence of an oscillating strain field.

Figure 2e shows the numerical simulation extracted from this framework within the rotating-wave approximation of both the main and sideband NMR spectra associated with 69Ga nuclei (see Methods). The simulation not only reproduces the sideband NMR peaks but also the ratio of the signal amplitude between the main peak and the sidebands as observed in the experiments. However the simulated sidebands are narrower than the main NMR peak and this feature is not seen in the experimental spectrum as this is acquired from an ensemble average (in contrast to the simulation) that is inhomogeneously broadened by the spatial distribution of the conduction electrons and the strain. This agreement with the theory confirms that the observed sideband peaks in Fig. 2b–d are indeed associated with nuclear spin transitions aided by electromechanical phonons via the quadrupole coupling.

Dispersive shifts induced by a driven mechanical resonator

From the overall similarity between our system and a circuit QED device embedded with an electromechanical resonator42, one can predict frequency shifts in the NMR caused by a driven mechanical resonator. This feature resembles the ac-Stark shift in a circuit QED system2,43 but now the driven mechanical motion that is off-resonant with the qubit transition frequency is treated as Floquet perturbation resulting in an energy shift, that was dubbed as the mechanical/phonon ac-Stark shift42.

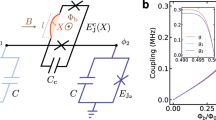

In order to investigate this effect in the present system, the NMR spectra of 75As nuclei were measured under the influence of intense AC electromechanical strain as shown in Fig. 3b. The bottom spectrum shows the NMR at zero mechanical displacement with a doublet peak structure as indicated by the solid circle (main peak) and open square (sub peak). However this figure also reveals that as the mechanical displacement is increased the main peak undergoes a blue shift whereas the sub peak remains fixed. To elucidate the underlaying physics of these observations, the NMR spectra are simulated using the same model Hamiltonian in Eq. (1) that describes nuclear spins under the influence of a rapidly oscillating quadrupole interaction arising from the driven electromechanical motion (see Methods) and are shown in Fig. 3c. The simulated NMR spectra (generated using the same parameters as in Fig. 2e but now with a variable displacement x(t)) reproduce the observed frequency shift, i.e., blue shift of the main peak (solid circle) and no shift of the sub peak (open square), again confirming that the experimental observations can be accommodated by the oscillating quadrupole Hamiltonian. To further quantify the simulated spectra, the experimental NMR frequencies of the main- and sub-peaks extracted from the measured NMR spectra are collated as a function of the physical displacement of the fundamental flexural mode x1. The resultant plot in Fig. 3d shows that the experimental frequency shift agrees with the simulated frequency shift.

In order to decipher the mechanisms underlying the observed frequency shift, the model Hamiltonian is further analyzed. In the absence of a quadrupole interaction between nuclei and mechanics, the bare nuclei with I = 3/2 shows degenerate Zeemann split states that are equally spaced by ħω0 as shown in Fig. 4. Next the quadrupole interaction is treated using Floquet perturbation theory (see Methods), which notably indicates that the dynamic (oscillating) component of the perturbation term has no contribution at the first order while it has a non-zero value at higher order. Consequently the first-order energy shift δ can simply be induced by static mechanical strain. The analytical expression of δ (see Methods for the derivation) indicates that its sign is positive (negative) for \(\left| {m = \pm 1{\mathrm{/}}2} \right\rangle\) \(\left( {\left| { \pm 3/2} \right\rangle } \right)\), which in turn lifts degeneracy as depicted in Fig. 4 and is experimentally observed as split NMR peaks even in the absence of ac strain in the lowest plot in Fig. 3b. Indeed, such NMR peak structure is commonly observed in GaAs heterostructures15 and is due to residual static strain that is incorporated during crystal growth and nano fabrication. Similarly, the sign of the second-order energy shift χ is positive (negative) for \(\left| { - 1{\mathrm{/}}2} \right\rangle\) and \(\left| { - 3{\mathrm{/}}2} \right\rangle\) (\(\left| {1{\mathrm{/}}2} \right\rangle\) and \(\left| {3{\mathrm{/}}2} \right\rangle\)) and the dynamical electromechanical strain only blue shifts the resonant transition \(\left| {1{\mathrm{/}}2} \right\rangle \leftrightarrow - \left| {1{\mathrm{/}}2} \right\rangle\), whereas the other transitions remain unchanged as shown in Fig. 4. This is in contrast to the case with static strain where the transition \(\left| {3{\mathrm{/}}2} \right\rangle \leftrightarrow \left| {1{\mathrm{/}}2} \right\rangle\) \(\left( {\left| { - 3{\mathrm{/}}2} \right\rangle \leftrightarrow \left| { - 1{\mathrm{/}}2} \right\rangle } \right)\) is blue (red) shifted while the \(\left| {1{\mathrm{/}}2} \right\rangle \leftrightarrow \left| { - 1{\mathrm{/}}2} \right\rangle\) transition remains unchanged. Consequently in the NMR spectra shown in Fig. 3b, d, the blue shifting main peak corresponds to the transition \(\left| {1{\mathrm{/}}2} \right\rangle \leftrightarrow \left| { - 1{\mathrm{/}}2} \right\rangle\) stemming from non-adiabatic dynamical strain originating from electromechanical phonons, whilst the sub peak (open square) corresponds to the \(\left| { - 3{\mathrm{/}}2} \right\rangle \leftrightarrow \left| { - 1{\mathrm{/}}2} \right\rangle\) transition which arises from the residual static strain given by −2δ.

Energy diagram of the nuclei under electromechanical strain. The energy level diagram of the nuclear spin I = 3/2 under the influence of static and dynamic mechanical strain. δ (χ) represents the energy level shift induced by static (dynamic) mechanical strain. The transitions labeled with the open square and solid circle correspond to the features in the NMR spectra in Fig. 3b, c with the same markings. The transition given by the solid triangle, although marked in Fig. 3b, c, is actually not observed in both the experiment and the simulation due to it being masked by the blue shifting main peak

Discussion

The NMR spectra of 75As, 69Ga, and 71Ga nuclei under the influence of intense periodic lattice strain induced by the large displacements of a strongly-driven doubly clamped electromechanical resonator were investigated. The resultant resistively detected NMR showed sideband peaks, which indicated the parametric coupling between nuclei and mechanics with the nuclear spin transitions assisted by electromechanical phonons. In addition, NMR frequency shifts were also observed that stemmed from non-adiabatic dynamics that scaled with the mechanical displacements. The agreement with theoretical modeling in both experiments confirms that our system faithfully implements dynamical coupling between a nuclear spin ensemble and an electromechanical resonator via mechanical strain.

In the present system, frequency shifts in the mechanical resonance from the NMR have yet to be observed, which indicates that the strain-mediated coupling observed in this system corresponds to a weak coupling regime. For more advanced dynamic effects such as coherent state transfer between a nuclear spin ensemble and electromechanical phonons and electromechanical detection of the NMR requires stronger coupling between nuclei and mechanics. In case of an ensemble, the effective coupling can be scaled with \(\sqrt {N_{\mathrm{P}}N_{{\mathrm{NS}}}}\) due to collective effects44,45, where NNS is the number of nuclear spins equally coupled to the mechanical resonator which contains NP phonons. Indeed such collective enhancement of coupling enables quantum entanglement to be generated between an ensemble and a resonator as demonstrated with an electron spin ensemble17,18,46. To address the future possibility of accessing the strong-coupling regime in this platform, the coupling rate between a single 75As nucleus and the zero-point motion of the resonator is estimated to be g0 ~ A1xZP = 0.15 mHz, where xzp = 3 fm is the amplitude of the zero-point fluctuations in the present mechanical resonator40. The strong-coupling regime requires \(\sqrt {N_{\mathrm{P}}N_{{\mathrm{NS}}}} g_0\) > max(ΔfM, ΔfNS), where ΔfM (ΔfNS) is the frequency bandwidth of the mechanical resonance (NMR peak). In the present work, ΔfM = 25 Hz and ΔfNS = 5 kHz, where the NMR spectrum is inhomogeneously broadened. However N ~ 1010 nuclear spins can be obtained in a volume of ~(100 nm)3, which is much smaller than the electromechanical resonator, in which case the strong-coupling regime is achievable with NP ~ 104 phonons, where these requirements would be accessible by simply optimizing the design of the resonator.

Further enhancement of this parametric coupling is necessary to achieving quantum coherent coupling, i.e., strong-coupling with NP < 1. This objective could be attained by using strain-engineered soft-clamped ultrahigh-Q mechanical resonators47,48, which can have a narrow linewidth down to mHz, and by improving the crystal quality to suppress the inhomogeneous broadening of the NMR spectrum as well as using quantum dots for highly polarized nuclear spin states49. On the other hand, a resonator with the frequency greater than the NMR frequency would be required for sideband cooling3,4,5,6,7,50 of the nuclear spins which would necessitate changing the material of the resonator and/or making it shorter and lighter where both could be achieved with semiconductor nanowires51,52. For future application to a quantum coherent hybrid system, the decoherence induced by the unpolarized nuclear spins, which are coupled to mechanical motion at the clamping points (but unpolarized by the electron transport) needs to be suppressed. An optimized device structure where the mechanically strained clamping points completely overlap with the nuclei polarized from the electron transport can in principle achieve this objective. Ultimately optical access to the sample will enable the nuclear bath in the entire resonator to be polarized22,53, thus enabling quantum coherent coupling between nuclei and phonons. Our observation of dynamical coupling between an nuclear spin ensemble and electromechanical phonons combined with these improvements is a prototype for electromechanical resonator-nuclear spin hybrid systems.

Methods

Sample fabrication

A doubly clamped electromechanical resonator with a length of 50 μm, width of 6 μm, and a thickness of 1 μm was fabricated from high-quality modulation-doped GaAs/Al0.3Ga0.7As heterowafer grown by molecular beam epitaxy on an undoped GaAs [100] substrate39,40. The beam resonator was defined along the [011] crystal axis. A single heterojunction located 90 nm below the surface sustains a two-dimensional electron gas (2DEG) with density n = 2.7 × 1011 cm−2. The main heterolayer that constitutes the beam resonator was grown on an aluminum-rich Al0.65Ga0.35As sacrificial layer to enable it to be suspended from the substrate. The fine mesa structure on the clamping points was defined by electron-beam lithography and wet-etching. The antenna gate and the Schottky electrodes formed thereon were fabricated via electron-beam lithography and deposited with 1 nm/25 nm of Cr/Au. The final step to suspend the beam resonator was defined by photo lithography and wet-etched to expose the sacrificial layer. The sacrificial layer was then selectively removed with dilute hydrogen fluoride (10 wt%).

Measurement setup

Supplementary Figure 1a shows the experimental setup. All measurements were performed in a high-vacuum insert (<10−5 Pa) in a dilution refrigerator with a base temperature (<80 mK). Source-drain current Isd is measured in a two-terminal configuration using a source measure unit with a bias voltage Vsd. In order to irradiate the RF transverse magnetic field in the NMR measurements, a signal generator is connected to one end of the antenna gate, while the other is grounded at low temperature so as to apply RF current IRF with frequency ωRF. The input RF power was fixed at −35 dBm throughout the measurements. The transverse rf field Bx is about 0.8 mT estimated from the input power and the resistance of the antenna gate. On the other hand, variable actuation voltage Va was applied to the upper Schottky gate electrode fabricated on the left clamping point using a function generator while the 2DEG beneath the gate is grounded as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1a, b. The resulting piezovoltage arising from the motion of the beam at the lower gate was amplified by a home-made HEMT-based cryogenic amplifier with the input load resistor of RL = 1 kΩ followed by a commercially available amplifier (NF SA-220F5) with a total voltage gain of ~200 VV−1. The amplified voltage signal was then measured with a lock-in amplifier phase-locked to the function generator. The details for this amplification setup are also available in refs.39,40.

Resistively detected NMR

The resistively detected NMR method relies on contact hyperfine interaction between conduction electrons and nearby nuclei, thereby enabling current-induced dynamical nuclear polarization (DNP), as well as resistive detection15,21,54,55,56. In our device, a shallow mesa sustaining a 2DEG was patterned onto the right clamping point. A static magnetic field B0 was then applied perpendicular to the 2DEG. Supplementary Figure 1c shows the two-terminal resistance measured as a function of B0, showing the integer quantum Hall plateaus. In the quantum Hall regime, current is carried by conduction electrons flowing along two counter-propagating edge channels. In order to selectively polarize nuclear spins and detect their spin states solely at the clamping point, negative bias voltage Vg is applied to the Schottky electrode to form a narrow constriction at the right clamping point as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1a, b. When a large Vsd is applied, a large electric field owing to a high current density at the narrow constriction locally breaks down the quantum Hall state that entails spin flip-flop events between hyperfine-coupled nuclei and electrons. As a consequence of these spin flip-flop events, local nuclei at the clamping point can be spin-polarized, known as DNP56,57,58,59. The number of nuclei in this interaction is estimated to be ~109 or less from the effective volume of the constriction, which is roughly 1 μm × 1 μm × 20 nm.

The hyperfine field generated by the spin-polarized nuclei modifies the Zeeman energy of the electron and thereby alters the backscattering probability which is manifested as a change in Isd. Supplementary Figure 1d shows the real time evolution of Isd, after the abrupt application of Vsd = 13.2 mV at B0 = 3.5 T (ν ≈ 3.15) with Vg = −0.45 V to induce breakdown, which reveals a slow decrease for the first 30 s followed by a saturation. The observed decrease in Isd can be attributed to current-induced DNP resulting in a 20% spin polarization estimated from the numerical simulations of the NMR spectra. Since this DNP was observed only when Vg value is large enough to completely deplete the 2DEG underlying the electrode, it ensures that the DNP and its resistive detection are taking place solely in the vicinity of the narrow constriction, i.e., at the clamping point. After waiting for Isd to saturate, ωRF is slowly swept at a rate of 3 kHz min−1. In order to resolve the fine peak structures in the NMR, (ΔIsd)2 is plotted as shown in Fig. 3b. When ωRF matches the transition frequency of nuclear spin states, a coherent oscillation is driven that leads to the depolarization of the nuclei. The resultant change in the hyperfine field due to the depolarized nuclei modifies Isd that manifests itself as an NMR peak as shown in Figs. 1d and 3b. The NMR detection via the electronic transport measurements has a fluctuation of about 0.3 nA that originates from charge fluctuation in the heterostructure. Because of this current fluctuation, the signal-to-noise ratio in the NMR signal ranges from 2 to 10.

In this work, an NMR signal was observed in the magnetic field range of 3.1 < B0 < 3.55 T, which corresponds to a transition from filling factor ν = 4 to ν = 3 quantum Hall states as highlighted in Supplementary Fig. 1c.

Sideband NMR spectra

The NMR spectra on the red/blue sidebands shown in Fig. 2e can in principle be obtained by calculating the time evolution via the master equation for the Hamiltonian in Eq. (1). However, the full numerical time evolution without approximation was slow to execute due to the low transition rate of the sideband NMR. Instead a numerical simulation of the Hamiltonian, approximated using the rotating-wave approximation, is employed. Equation (1) is evaluated with x(t) = x1cos(ωMt) and by moving to a non-uniform rotating frame via a unitary transformation:

This yields a transformed Hamiltonian:

The second term in the right hand side describes the main NMR peak at ωRF = ω0, while the third (fourth) term corresponds to the blue (red) sideband. Here \(\hat I_{{\mathrm{side}}}\) describes the transition of the nuclear spin states at the sidebands and is defined as

where the first (last) two terms describe the transition between \(\left| {1{\mathrm{/}}2} \right\rangle\) and \(\left| {3{\mathrm{/}}2} \right\rangle\) (\(\left| { - 1{\mathrm{/}}2} \right\rangle\) and \(\left| { - 3{\mathrm{/}}2} \right\rangle\)) states. In order to calculate the time evolution from Eq. (4) at the red (blue) sideband, a transition to the frame rotating at frequency ωRF ± ωM along the z-axis is made using the transformation \(\hat U_2\) = \({\mathrm{exp}}\left\{ {i\left( {\omega _{{\mathrm{RF}}} \pm \omega _{\mathrm{M}}} \right)t\hat I_z} \right\}\) followed by the rotating-wave approximation to get

whose time evolution can then be easily calculated. It should be noted that, because of the rotating-wave approximation, this simulation does not reproduce the frequency shift induced by the ac strain, which is observed in Fig. 3b. Hence the main peak in Fig. 2e shows no frequency shift and this can only be reproduced in the full numerical simulation without the rotating-wave approximation as shown in Fig. 3c, d.

Numerical simulation of the NMR spectra

For the numerical simulations, the quadrupole coupling constants A1 and A2 in Eq. (2) are determined from a finite element method analysis of the strain associated with the fundamental mode (see Supplementary Note 1). We obtain A1 = 0.49 meV m−1 and A2 = −0.6 meV m−1 for 75As, A1 = 0.16 meV m−1 and A2 = −0.14 meV m−1 for 69Ga. The displacement is measured at the center of the beam (see point x in Supplementary Fig. 2a) and is decomposed into static and dynamic parts as x(t) = x0 + x1 cos(ωMt). The time evolution for the density matrix ρ of the nuclear spin is then calculated using the von Neumann equation13,57:

The temporal evolution of this first-order ordinary differential equation is extracted using the fourth-order Runge–Kutta method with a time step of Δt = 10−9 s. The upper panels in Supplementary Fig. 3a, b show the simulated temporal evolution of \(\left\langle {\hat I_z} \right\rangle = {\mathrm{Tr}}\left\{ {\rho \hat I_z} \right\}\) with two different mechanical displacements (a) x1 = 0 and (b) x1 = 1.1 μm. Both plots show the first 1.5 periods of the coherent oscillation. From this time evolution, the normalized oscillation amplitude in \(\left\langle {\hat I_z} \right\rangle\) can be determined as shown in the lower panels in Supplementary Fig. 3a, b. In this simulation, the shape of the measured NMR spectra (Fig. 3b) is reproduced by adjusting x0 and ρ(0) values. The experimental spectrum exhibits two features: (i) the peak splitting in the absence of driven mechanical strain x1 = 0 is ~5 kHz, and (ii) the prominent peak’s blue shift (solid circle) whilst the sub peak (open square) is stationary. The former feature is reproduced with x0 = −22 nm, whereas the latter feature is reproduced by ρ(0) = {ρ3/2, ρ1/2, ρ−1/2, ρ−3/2} = {0.15, 0.2, 0.27, 0.36}, which is determined from a Boltzman distribution with a negative spin temperature of −4 mK. The negative temperature indicates that the nuclear spin state is population inverted due to the negative g-factor of the conduction electrons in GaAs57. Figure 3c displays the resultant normalized oscillation amplitude extracted from the time evolution of \(\left\langle {\hat I_z} \right\rangle = {\mathrm{Tr}}\left\{ {\rho \hat I_z} \right\}\) at different mechanical displacements.

Floquet perturbation analysis

The quadrupole interaction experienced by the nuclei can be described as a time-periodic perturbation that induces a level shift and thus lifts the degeneracy of the Zeeman split energy states. To quantify this level shift a Floquet perturbation analysis60,61 of the above Hamiltonian is employed to derive the energy diagram in Fig. 4 by decomposing it to: \(\hat H = \hat H_{\mathrm{Z}} + x(t)\hat J_{\mathrm{Q}}\) with x(t) = x0 + x1 cos(ωMt). In this perturbative approach the first term is the bare Hamiltonian whose eigenenergy \(E_m^{(0)}\) is exactly solved as \(\hat H_{\mathrm{Z}}\left| m \right\rangle = E_m^{(0)}\left| m \right\rangle\), while the second term is treated as a periodic time-dependent perturbation that causes an energy shift for \(\left| m \right\rangle\). The eigenenergies Em for the full Hamiltonian are then expanded as a perturbative series: Em = \(E_m^{(0)} + E_m^{(1)} + E_m^{(2)} + \cdots\). The striking conclusion from the Floquet theory is that the oscillating components (∝x1) have no contribution in the first order but a finite contribution in higher order. The first-order energy shift is then calculated as

with a positive (negative) sign for \(\left| { \pm 3{\mathrm{/}}2} \right\rangle\) \(\left( {\left| { \pm 1{\mathrm{/}}2} \right\rangle } \right)\). Here only the diagonal part (real part) of \(\hat J_{\mathrm{Q}}\) contributes to the energy shift. Similarly, the second-order energy shift is calculated as

The numerators in this equation can be evaluated as

and are independent of m. In the second order, the off-diagonal part (imaginary part) of \(\hat J_{\mathrm{Q}}\) has a non-zero contribution. This leads to

where the negative (positive) sign is for \(\left| {3{\mathrm{/}}2} \right\rangle\), and \(\left| {1{\mathrm{/}}2} \right\rangle\) (\(\left| { - 3{\mathrm{/}}2} \right\rangle\), and \(\left| { - 1{\mathrm{/}}2} \right\rangle\)) with approximately: x0/x1 ≈ 0, and ωM/ω0 ≈ 0.

Calibration of mechanical displacement and strain

In the experiments, the mechanical motion can be detected via the piezovoltage Vd, from which the corresponding displacement x1 at the center of the beam resonator (point x in Supplementary Fig. 2a) is determined via x1 = Vd/(5 × 103 V m−1). This calibration was derived by fitting the experimentally observed NMR frequency shift to the simulated frequency shift as shown in Fig. 3d. The electromechanical strain can be determined from this displacement calibration via a finite element method simulation (see Supplementary Note 1). To ensure validity of this calibration, the mechanical displacement is also quantified from the onset of nonlinearity. The onset of nonlinearity in a doubly clamped beam resonator can be estimated analytically from xc ≈ t\(\sqrt {2{\mathrm{/}}0.528Q\left( {1 - \nu ^2} \right)}\) ≈ 12 nm, where t = 1 μm is the thickness of the beam and ν = 0.31 is the Poisson ratio of GaAs41,52. Experimentally, nonlinearity emerges at Vd ~ 0.2 mV as shown in Fig. 1b and in the strong driving regime at point 5 in Fig. 3a, the mechanical amplitude is roughly 30 times larger than this onset, and is estimated to be 30xc ≈ 0.4 μm.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Change history

04 September 2018

This Article was originally published without the accompanying Peer Review File. This file is now available in the HTML version of the Article; the PDF was correct from the time of publication.

References

Wallraff, A. et al. Strong coupling of a single photon to a superconducting qubit using circuit quantum electrodynamics. Nature 431, 162–167 (2004).

Boissonneault, M., Gambetta, J. A. & Blais, A. Dispersive regime of circuit QED: photon-dependent qubit dephasing and relaxation rates. Phys. Rev. A. 79, 013819 (2009).

Aspelmeyer, M., Kippenberg, T. J. & Marquardt, F. Cavity optomechanics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 86, 1391–1452 (2014).

Teufel, J. D., Donner, T., Castellanos-Beltran, M. A., Harlow, J. W. & Lehnert, K. W. Nanomechanical motion measured with an imprecision below that at the standard quantum limit. Nat. Nanotechnol. 4, 820–823 (2009).

Mahboob, I., Nishiguchi, K., Okamoto, H. & Yamaguchi, H. Phonon-cavity electromechanics. Nat. Phys. 8, 387–392 (2012).

Schliesser, A., Arcizet, O., Rivière, R., Anetsberger, G. & Kippenberg, T. J. Resolved-sideband cooling and position measurement of a micromechanical oscillator close to the Heisenberg uncertainty limit. Nat. Phys. 5, 509–514 (2009).

Teufel, J. D. et al. Sideband cooling of micromechanical motion to the quantum ground state. Nature 475, 359–363 (2011).

Verhagen, E., Deléglise, S., Weis, S., Schliesser, A. & Kippenberg, T. J. Quantum-coherent coupling of a mechanical oscillator to an optical cavity mode. Nature 482, 63–67 (2012).

Riedinger, R. et al. Non-classical correlations between single photons and phonons from a mechanical oscillator. Nature 530, 313–316 (2016).

Palomaki, T. A., Teufel, J. D., Simmonds, R. W. & Lehnert, K. W. Entangling mechanical motion with microwave fields. Science 342, 710–713 (2013).

Riedinger, R. et al. Remote quantum entanglement between two micromechanical oscillators. Nature 556, 473–477 (2018).

Ockeloen-Korppi, C. F. et al. Stabilized entanglement of massive mechanical oscillators. Nature 556, 478–482 (2018).

Leuenberger, M. N., Loss, D., Poggio, M. & Awschalom, D. D. Quantum information processing with large nuclear spins in GaAs semiconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 207601 (2002).

Jones, J. A. Quantum computing with NMR. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 59, 91–120 (2011).

Hirayama, Y. et al. Electron-spin/nuclear-spin interactions and NMR in semiconductors. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 24, 023001 (2009).

Jones, J. A. et al. Magnetic field sensing beyond the standard quantum limit using 10-spin NOON states. Science 324, 1166–1168 (2009).

Kubo, Y. et al. Strong coupling of a spin ensemble to a superconducting resonator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 140502 (2010).

Kubo, Y. et al. Hybrid quantum circuit with a superconducting qubit coupled to a spin ensemble. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 220501 (2011).

Petersson, K. D. et al. Circuit quantum electrodynamics with a spin qubit. Nature 490, 380–383 (2012).

Bienfait, A. et al. Reaching the quantum limit of sensitivity in electron spin resonance. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 253–257 (2016).

Kawamura, M. et al. Strain-induced enhancement of electric quadrupole splitting in resistively detected nuclear magnetic resonance spectrum in quantum Hall systems. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 032102 (2010).

Ono, M. et al. Strain and origin of inhomogeneous broadening probed by optically detected nuclear magnetic resonance in a (110) GaAs quantum well. Phys. Rev. B 89, 115308 (2014).

Levitt, M.H. Spin dynamics: basics of nuclear magnetic resonance. (Wiley: New Jersey, 2015.

Chekhovich, E. A. et al. Nuclear spin effects in semiconductor quantum dots. Nat. Mater. 12, 494–504 (2013).

Dzhioev, R. I. & Korenev, V. L. Stabilization of the electron-nuclear spin orientation in quantum dots by the nuclear quadrupole interaction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 037401 (2007).

Maletinsky, P., Kroner, M. & Imamoglu, A. Breakdown of the nuclear-spin-temperature approach in quantum-dot demagnetization experiments. Nat. Phys. 5, 407–411 (2009).

Chekhovich, E. A. et al. Structural analysis of strained quantum dots using nuclear magnetic resonance. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 646–650 (2012).

Bulutay, C. Quadrupolar spectra of nuclear spins in strained InxGa1−xAs quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 85, 115313 (2012).

Chekhovich, E. A., Hopkinson, M., Skolnick, M. S. & Tartakovskii, A. I. Suppression of nuclear spin bath fluctuations in self-assembled quantum dots induced by inhomogeneous strain. Nat. Commun. 6, 6348 (2015).

Guerrier, D. J. & Harley, R. T. Calibration of strain vs nuclear quadrupole splitting in III-V quantum wells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 70, 1739–1741 (1997).

Salis, G. et al. Optical manipulation of nuclear spin by a two-dimensional electron gas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 2677–2680 (2001).

Eickhoff, M., Lenzmann, B., Suter, D., Hayes, S. E. & Wieck, A. D. Mapping of strain and electric fields in GaAs/AsxGa1−xAs quantum-well samples by laser-assisted NMR. Phys. Rev. B 67, 085308 (2003).

Poggio, M. & Awschalom, D. D. High-field optically detected nuclear magnetic resonance in GaAs. Appl. Phys. Lett. 86, 182103 (2005).

Knotz, H., Holleitner, A. W., Stephens, J., Myers, R. & Awschalom, D. D. Spatial imaging and mechanical control of spin coherence in strained GaAs epilayers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 88, 241918 (2006).

Kondo, Y. et al. Multipulse operation and optical detection of nuclear spin coherence in a GaAs/AlGaAs quantum well. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 207601 (2008).

Ono, M., Ishihara, J., Sato, G., Ohno, Y. & Ohno, H. Coherent manipulation of nuclear spins in semiconductors with an electric field. Appl. Phys. Express 6, 033002 (2013).

Franke, D. P. et al. Interaction of strain and nuclear spins in silicon: quadrupolar effects on ionized donors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 057601 (2015).

Sundfors, R. K. Exchange and quadrupole broadening of nuclear acoustic resonance line shapes in the III-V semiconductors. Phys. Rev. 185, 458–472 (1969).

Okazaki, Y., Mahboob, I., Onomitsu, K., Sasaki, S. & Yamaguchi, H. Quantum point contact displacement transducer for a mechanical resonator at sub-Kelvin temperatures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, 192105 (2013).

Okazaki, Y., Mahboob, I., Onomitsu, K., Sasaki, S. & Yamaguchi, H. Gate-controlled electromechanical backaction induced by a quantum dot. Nat. Commun. 7, 11132 (2016).

Ekinci, K. L. & Roukes, M. L. Nanoelectromechanical systems. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 76, 061101 (2005).

Pirkkalainen, J.-M. et al. Hybrid circuit cavity quantum electrodynamics with a micromechanical resonator. Nature 494, 211–215 (2013).

Schuster, D. I. et al. AC-stark shift and dephasing of a superconducting qubit strongly coupled to a cavity field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 123602 (2005).

Diniz, I. et al. Strongly coupling a cavity to inhomogeneous ensembles of emitters: potential for long-lived solid-state quantum memories. Phys. Rev. A. 84, 063810 (2011).

Dooley, S. A. et al. Hybrid-systems approach to spin squeezing using a highly dissipative ancillary system. New J. Phys. 18, 053011 (2016).

Zhu, X. et al. Coherent coupling of a superconducting flux qubit to an electron spin ensemble in diamond. Nature 478, 221–224 (2011).

Tsaturyan, Y., Barg, A., Polzik, E. S. & Schliesser, A. Ultracoherent nanomechanical resonators via soft clamping and dissipation dilution. Nat. Nanotechnol. 12, 776–783 (2017).

Ghadimi, A. H. et al. Elastic strain engineering for ultralow mechanical dissipation. Science 360, 764–768 (2018).

Baugh, J., Kitamura, Y., Ono, K. & Tarucha, S. Large nuclear overhauser fields detected in vertically coupled double quantum dots. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 096804 (2007).

Grajcar, M., Ashhab, S., Jphansson, J. R. & Nori, F. Lower limit on the achievable temperature in resonator-based sideband cooling. Phys. Rev. B 78, 035406 (2008).

Sansa, M., Fernández-Regúlez, M., Llobet, J., San Paulo, Á. & Pérez-Murano, F. High-sensitivity linear piezoresistive transduction for nanomechanical beam resonators. Nat. Commun. 5, 4313 (2014).

Husain, A. et al. Nanowire-based very-high-frequency electromechanical resonator. Appl. Phys. Lett. 83, 1240–1242 (2003).

Falk, A. L. et al. Optical polarization of nuclear spins in silicon carbide. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 247603 (2015).

Machida, T., Yamazaki, T., Ikushima, K. & Komiyama, S. Coherent control of nuclear-spin system in a quantum-Hall device. Appl. Phys. Lett. 82, 409–411 (2003).

Kawamura, M. et al. Electrical polarization of nuclear spins in a breakdown regime of quantum Hall effect. Appl. Phys. Lett. 90, 022102 (2007).

Keane, Z. K. et al. Resistively detected nuclear magnetic resonance in n- and p-type GaAs quantum point contacts. Nano. Lett. 11, 3147–3150 (2011).

Yusa, G., Muraki, K., Takashina, K., Hashimoto, K. & Hirayama, Y. Controlled multiple quantum coherences of nuclear spins in a nanometre-scale device. Nature 434, 1001–1005 (2005).

Chida, K. et al. Shot noise induced by electron-nuclear spin-flip scattering in a nonequilibrium quantum wire. Phys. Rev. B 85, 041309 (2012).

Kawamura, M., Ono, K., Stano, P., Kono, K. & Aono, T. Electronic magnetization of a quantum point contact measured by nuclear magnetic resonance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 036601 (2015).

Sambe, H. Steady states and quasienergies of a quantum-mechanical system in an oscillating field. Phys. Rev. A. 7, 2203–2213 (1973).

Beloy, K. Theory of the ac Stark Effect on the Atomic Hyperfine Structure and Applications to Microwave Atomic Clocks. Ph. D thesis. (University of Nevada, Reno, 2009).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank H. Chudo, K. Chida, K. Harii, Y. Hirayama, J. Ieda, K. Koshino, Y. Matsuzaki, W. J. Munro, and M. Ono for fruitful discussions. This work was partly supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant No. 23241046, JP18H01156, and JP18H05258 and Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas No. JP15H05869.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.O. fabricated the device, performed the measurements, and analyzed the data and theoretical model. K.O. grew the GaAs heterostructure. S.S. supported the device fabrication. S.N. and N-H.K supported the numerical simulation. Y.O. I.M., and H.Y. wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Okazaki, Y., Mahboob, I., Onomitsu, K. et al. Dynamical coupling between a nuclear spin ensemble and electromechanical phonons. Nat Commun 9, 2993 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-05463-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-05463-3

This article is cited by

-

Nuclear spin quantum register in an optically active semiconductor quantum dot

Nature Nanotechnology (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.