Abstract

The central goal of crystal engineering is to control material function via rational design of structure. A particularly successful realisation of this paradigm is hybrid improper ferroelectricity in layered perovskite materials, where layering and cooperative octahedral tilts combine to break inversion symmetry. However, in the parent family of inorganic ABX3 perovskites, symmetry prevents hybrid coupling to polar distortions. Here, we use group-theoretical analysis to uncover a profound enhancement of the number of improper ferroelectric coupling schemes available to molecular perovskites. This enhancement arises because molecular substitution diversifies the range of distortions possible. Not only do our insights rationalise the emergence of polarisation in previously studied materials, but we identify the fundamental importance of molecular degrees of freedom that are straightforwardly controlled from a synthetic viewpoint. We envisage that the crystal design principles we develop here will enable targeted synthesis of a large family of new acentric functional materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ferroelectricity, i.e., the presence of a switchable electric polarisation, is an important property with many technological applications1. An early canonical ferroelectric was BaTiO3, with the broader family of ABX3 perovskite oxides now known to include a variety of ferroelectric systems2,3,4,5. The ferroelectric response of BaTiO3 originates from a second-order Jahn–Teller (SOJT) effect, in which the B-site cation Ti4+ displaces from the centre of its TiO6 coordination environment2,6. As this polar instability also acts as the primary order parameter, BaTiO3 is a proper ferroelectric. Despite the continuing discussion regarding the origin of polar coupling in BaTiO37, the general SOJT mechanism at play is rare and its generalisation is challenging, as it requires a d0 electronic configuration6. Hence, design approaches for new ferroelectric materials based on SOJT instabilities are limited and, moreover, the mechanism is difficult to couple with spin-active d-electron configurations, which has largely prevented its exploitation in the search for magnetoelectric multiferroics8. In fact, ferroelectricity is comparatively rare in bulk perovskite materials and BaTiO3 is much more of an exception than a rule9.

It is in this context that the concept of hybrid improper ferroelectricity is especially appealing10. A necessary condition for ferroelectricity is the presence of a polar space group, which in turn requires broken inversion symmetry. Simple inorganic perovskites contain two crystallographically distinct inversion centres (at the A- and B-site, respectively) and in BaTiO3, the zone-centre polar mode breaks both of these, driving the polarity11. Alternatively, in favourable cases, a combination of two or more modes—each non-polar in their own right—may collectively lift inversion symmetry and give rise to a polar secondary order parameter10,12. This so-called hybrid improper ferroelectricity mechanism is attractive from a crystal engineering perspective because it lends itself to design rules via group-theoretical analysis10. In addition, the mechanism does not preclude magnetic order10,13. Hence, using group-theoretical methods, it is possible to enumerate the symmetry breaking caused by given distortions of an aristotype and thereby predict the propensity for the formation of acentric structures. For simple inorganic perovskites, the accessible degrees of freedom—cooperative first-order Jahn–Teller (FOJT) distortions and octahedral tilting—all preserve the inversion centre of the B-site, and in order to enable hybrid improper ferroelectricity, additional symmetry breaking in the form of A-site cation order or layering is needed13,14,15.

A recent development in the broader field is the increased interest in molecular perovskite analogues16. These are solid compounds with the same ABX3 stoichiometry of conventional perovskites, but where A or X (or both) are molecular ions. This populous class of materials may be categorised according to the nature of the anionic linker: topical families include the organic–halide perovskites17,18, metal formates19,20, Prussian blue analogues21,22, azides23,24, dicyanamides25,26, hypophosphites27, thiocyanates28,29, and dicyanometallates30,31. The enhanced structural flexibility allowed by molecular species enables additional degrees of freedom unfeasible in conventional inorganic perovskites: unconventional tilts30,32, columnar shifts33, and multipolar order (Fig. 1)34,35. The first two of these correspond to rigid-unit modes (RUMs)36—i.e., phonon modes which propagate without deforming BX6 coordination geometries37,38. The larger number of RUMs in molecular perovskites is conceptually related to the additional flexibility driven by reduced connectivity in Ruddlesden–Popper phases39. By contrast, the presence of multipolar degrees of freedom reflects reorientations of non-spherical molecular A-site cations34,35,40.

Molecular perovskites and their degrees of freedom. a A perovskite oxide with the molecular congeners shown to scale. In all cases, the A-site cation is shown as spacefilling, with carbon in black, hydrogen in white, nitrogen in orange, and phosphorus in green. b Schematic illustrations of the various degrees of freedom accessible to molecular perovskites. c A combination of two such distortions—an unconventional tilt (left) and columnar shift (centre)—is responsible for the crystal symmetry of [NH4]Cd(HCOO)3 (right). Note that the unconventional tilt results in some neighbouring coordination octahedra rotating in the same sense, which is possible only because the X-site anions are molecular

In this paper, we show how these new types of structural degrees of freedom can combine to break inversion symmetry, hence establishing a new set of design rules for engineering acentric molecular perovskites. First, we introduce our general recipe for designing acentric materials. Second, we classify the various symmetry breaking ingredients accessible to molecular perovskites in terms of the irreducible representations of the high-symmetry perovskite aristotype. Third, we use these ingredients to construct the key ferroelectric coupling schemes. And, fourth, we illustrate how this approach can be used to rationalise the emergence of polarisation in a number of previously reported systems.

Results

Polarisation from trilinear coupling

The fundamental idea of our approach is to identify two distortions (A and B) of the parent \(Pm\bar 3m\) aristotype that are inherently non-polar but which, when combined, give rise to an additional polar degree of freedom (P) in the hettotype (child structure). In a Landau-style expansion of the free energy about the parent structure, this produces a third-order (trilinear) term βABP. As A and B are inherently non-zero if they are unstable with respect to the parent phase then—irrespective of the sign of the coefficient β—P will also adopt a non-zero (positive or negative) value in order to stabilise the free energy. We can use the idea of invariants analysis41 to identify the permissible third-order terms in the general free energy expansion; i.e., identify for which combinations of A and B one would expect coupling to P. For the zone-boundary/zone-centre distortions that we consider here, we find that such couplings may in fact be identified by inspection, as detailed in the following paragraphs.

Each distortion we consider can be described as transforming as an irreducible representation (irrep) of the parent space group \(Pm\bar 3m\) (Table 1, see Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1 for a more comprehensive list). The irrep labels are of the form \({\mathbf{k}}_\# ^ \pm\), where the symbol k denotes the propagation or wave vector of the distortion with respect to the parent structure. In our study we consider k = [0, 0, 0] (Γ), \(\left[ {\frac{1}{2},\,\frac{1}{2},\,\frac{1}{2}} \right]\) (R), \(\left[ {\frac{1}{2},\,\frac{1}{2},\,0} \right]\) (M), \(\left[ {0,\,\frac{1}{2},\,0} \right]\) (X), and symmetry equivalents thereof—these being the distortion periodicities most relevant to real examples. The + or − sign generally denotes that either one or the other inversion centre, related to each other by a origin shift (i.e., a translation by \(\frac{1}{2},\,\frac{1}{2},\,\frac{1}{2}\)), is broken. Clearly, any collective ordering or distortion that fails to break both these inversion centres at once cannot lead to an improper ferroelectric coupling, and it is this point that underlies our arguments based on invariants analysis presented below.

As any term that features in the free energy expansion about the parent phase must conserve both crystal momentum and parity with respect to the inversion symmetry, it can quickly be seen that any two distortions transforming as X+ and X−, or as M+ and M−, or as R+ and R− must couple to a non-centrosymmetric (and in general polar) distortion P, which itself transforms as Γ−. On the other hand, any two distortions to the parent phase that have either a different propagation vector and/or the same sign with respect to inversion parity cannot produce such a coupling to P. Hence, combinations such as X+ and R−, or M− and M− etc., may be immediately discounted. As a final point, we note that higher-order coupling terms such as (X+, M+, R−), (X−, M−, R−), and so on also produce a fourth-order coupling in P, provided that the rules for preservation of crystal momentum and parity are observed.

Distortions in molecular perovskites

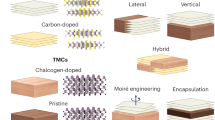

In the context of molecular perovskites, the relevant collective distortions involve conventional tilts, unconventional tilts, columnar shifts, FOJT effects, and multipolar A-site order. The combinations of distortions capable of driving polarity are shown in Fig. 2, with an example of a representative child space group given for each specific combination. For analysis of related third- and fourth-order coupling schemes, see Supplementary Tables 2 and 3. Our main result is the clear distinction in number of possibilities for inversion symmetry breaking in molecular perovskites relative to their conventional ceramic counterparts (inset in Fig. 2). Indeed, we find that either multipolar order (driven by molecular substitution on the A-site) or the activation of columnar shifts (driven by molecular substitution on the X-site) is by itself sufficient to break inversion symmetry when correctly coupled to any other order parameter. Hence, in the design of ferroelectric molecular perovskites, molecular substitution need involve only one site (A or X) and polar ground states are theoretically possible both for A-site-only substituted perovskites (e.g., the organic–halide perovskites) and for their X-site-only substituted cousins (e.g., Prussian blue analogues).

Coupling schemes in molecular perovskites. The accessible distortion types are given at the top of each column and the right of each row: conventional tilts, unconventional tilts, columnar shifts, Jahn–Teller distortions, and multipole ordering. For each combination of distortions, a representative space group is shown and the colour indicates whether coupling of the two distortions can ever drive a polar distortion (green) or not (grey). The inset shows the corresponding coupling scheme for conventional inorganic perovskites

Arguably one of the easiest distortions to control from a materials design perspective is that of A-site multipolar order. Many common organic cations are polar—their charge being localised on a single atom. Moreover, both rod-like (prolate) and disc-like (oblate) cations possess quadrupole moments. This includes common cations such as methylammonium \(\left( {{\mathrm{CH}}_3{\mathrm{NH}}_3^ + } \right)\), hydrazinium \(\left( {{\mathrm{NH}}_2{\mathrm{NH}}_3^ + } \right)\), guanidinium \(\left( {{\mathrm{C}}\left( {{\mathrm{NH}}_2} \right)_3^ + } \right)\), and imidazolium. Higher-order multipoles are also possible, such as the hexapole moment of guanidinium and the octupole moment of ammonium and tetramethylammonium. Table 1 makes clear that equivalent types of zone-boundary dipolar and quadrupolar order transform as irreps with opposite sign with respect to inversion parity. Hence, the incorporation of cations which support both dipole and quadrupole moments gives access to a greatly increased number of possible improper couplings to bulk polarisation.

Relevance to polar molecular perovskites

But to what extent are these predictions borne out in practice? There are in fact a number of hybrid ferroelectric molecular perovskites already reported in the literature. In Table 2 we list the various molecular perovskites known to adopt polar structure types, and present the corresponding irreps responsible for the emergence of polarisation (noting that it is not always possible to identify unambiguously the primary order parameters from a single crystal structure alone). We now proceed to rationalise the emergence of polarisation in detail for two of these systems in light of the analysis presented above. For ease of illustration, we give two-dimensional representations of the relevant coupling schemes in Fig. 3.

Inversion symmetry breaking in 2D molecular perovskites. Left: both unconventional tilting and columnar shifts yield the plane group p2gm, but with different origins. When coupled together, the resulting plane group is pg, which lacks inversion symmetry. A conceptually related combination of octahedral tilts and shifts is responsible for inversion symmetry breaking in [NH4]Cd(HCOO)3, which crystallises in Pna21. Right: a C-type cooperative Jahn–Teller distortion lowers 2D molecular perovskite symmetry to p4gm, whereas antiferrohexapolar order gives a p2gm cell with a different origin. When combined, the two distortions generate the polar plane group pg. This is a 2D analogue of the hybrid coupling found in GuaCu(HCOO)3

Our first experimental example is that of the formate perovskite [NH4]Cd(HCOO)3, first synthesised several decades ago42 and revisited more recently for its dielectric properties43. The system crystallises in the polar space group Pna21, with the formate anion adopting a mixed syn-anti binding mode. This binding geometry is less prevalent than the anti-anti binding mode typically observed for formate-bridged perovskites20,44,45,46,47, and is related to the low tolerance factor47. The structure contains a considerable planar shift alternating along the c direction which is described by the irrep \({\mathrm{X}}_5^ +\). It also supports an unconventional tilt, which transforms as \({\mathrm{X}}_5^ -\). These distortions yield the polar space group Cmc21, which in combination with the conventional in-phase tilting \(\left( {{\mathrm{M}}_2^ + } \right)\) gives Pna21. Despite the fact that three order parameters are needed to fully account for the observed space group, the shift \(\left( {{\mathrm{X}}_5^ + } \right)\) and unconventional tilt \(\left( {{\mathrm{X}}_5^ - } \right)\) are sufficient to account for inversion symmetry breaking.

Our second example is that of [Gua]Cu(HCOO)3 (where Gua = \({{\mathrm{C}}\left( {{\mathrm{NH}}_2} \right)_3^ + }\)), which also crystallises with Pna21 space group symmetry. In this case the coupling is between a cooperative Jahn–Teller distortion and multipolar A-site order. It is the only polar member of the family [Gua]M(HCOO)3 (M = Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn, Cd)44,48, and also the only Jahn–Teller-active member of the same family, which immediately identifies the importance of a collective Jahn–Teller distortion \(\left( {{\mathrm{M}}_3^ + } \right)\) in the coupling scheme. The multipolar order associated with the particular alignment of the Gua cation couches in fact two order parameters: the quadrupolar ordering \({\mathrm{X}}_5^ +\) (orientation of the guanidinium plane normal) and the hexapolar ordering \({\mathrm{R}}_5^ -\) (specific orientation around the threefold axis). The role of collective JT order in driving inversion symmetry breaking in this system has been identified previously, as has the intriguing possibility of magnetoelectric coupling in the hypothetical chromium(II) analogue GuaCr(HCOO)349,50. Quantum mechanical calculations estimate the maximum polarisation in this system to be 0.22 μC/cm2 50, which demonstrates that the achievable polarisations in these molecular perovskites is likely comparable to that of the Rochelle salts, for example51.

Propolar molecular perovskites

Drawing on this concept of inversion symmetry breaking via coupling to collective JT order, we flag the possibility of identifying ‘propolar’ molecular frameworks: i.e., systems such as [Gua]M(HCOO)3 with pre-existing structural distortions (tilts, multipolar order, …) such that superposition of JT order would be expected to give a polar state. In addition to the guanidinium transition-metal formates discussed above, we identify two additional molecular perovskites that satisfy this criterion for \({\mathrm{M}}_3^ +\)-type JT order (the most frequently observed). The first is the hypophosphite [Trz]Mn(H2PO2)3 (Trz = 1,2,4-triazolium, \({{\mathrm{C}}_2{\mathrm{N}}_3{\mathrm{H}}_{4}^ + }\))27, the structure of which is described by a coupling of layered shifts \(\left( {{\mathrm{X}}_5^ + } \right)\) and conventional a− tilts \(\left( {{\mathrm{R}}_5^ - } \right)\). The second is the formate perovskite [H2Im]Mn(HCOO)3 (HIm = imidazole, C3N2H4), which is isostructural and hence described in terms of the same distortion modes52. In both cases, substitution of Mn for Cu might reasonably be expected to drive hybrid improper ferroelectricity—a prediction that could be tested experimentally.

A related strategy is to ask, for a given structure type, what particular distortions need to be added to generate bulk polarisation? Whereas the most common space group for conventional perovskites is Pnma53, it is not yet clear what crystal symmetry—if any—is especially prominent amongst molecular perovskites16. Hence, we illustrate this strategy with the Pnma perovskite structure, mindful of the possibility of extrapolating to other structures as our collective understanding develops. The key distortions in the Pnma structure are two tilts—one in-phase \(\left( {{\mathrm{M}}_2^ + } \right)\) and the other out-of-phase \(\left( {{\mathrm{R}}_5^ - } \right)\). An additional antiferroelectric A-site cation displacement \(\left( {{\mathrm{X}}_5^ - } \right)\) appears as a secondary order parameter. Consequently, quadrupolar A-site order that transforms as either \({\mathrm{R}}_5^ +\) or \({\mathrm{X}}_5^ +\) irreps may provide the required coupling with the octahedral rotations \(\left( {{\mathrm{R}}_5^ - } \right)\) or anti-polar distortions \(\left( {{\mathrm{X}}_5^ - } \right)\). Alternatively, dipolar ordering transforming as \({\mathrm{M}}_3^ -\) or \({\mathrm{M}}_5^ -\) could couple to the octahedral rotations at the M-point \(\left( {{\mathrm{M}}_2^ + } \right)\). Hence, a molecular cation with both a dipolar moment and quadrupole moment, enclosed in a Pnma perovskite, will give rise to hybrid improper ferroelectricity, provided that the dipole moment orders at the M-point (or, trivially, at the Γ-point) or the quadrupole moment orders at the X- or R-point. To maximise the likelihood of such a situation, one should choose cations with both quadrupolar and dipolar moments, of which there are many examples; e.g., hydrazinium, imidazolium, and methylammonium. Steric considerations will stabilise orientational order of larger cations to lower temperatures, and design rules for controlling the type of quadrupolar order are now starting to emerge35. Hence, judicious choice of a molecular cation with the correct type of multipole moment may prove an important design strategy for engineering hybrid improper ferroelectricity.

Discussion

Hence, we can conclude that, from a group-theoretical viewpoint, perovskites with a molecular component are remarkably predisposed to crystallising in polar space groups. This attractive property is a result of the large number of polar coupling schemes generated by distortions accessible to molecular perovskites but inaccessible to conventional inorganic perovskites. We have identified specific combinations of structural distortions that lead to acentric structures and have thereby suggested possible routes for targeted material design. In particular, we highlight explicitly a number of propolar candidates, where the replacement of JT-inactive for JT-active transition-metal cations is likely to drive polarity. We have also found that either A-site quadrupolar order or the activation of columnar shifts—features that are unique to molecular perovskites—can drive polarisation when coupled to conventional (Pnma-type) distortions of the perovskite structure. There are several examples of hybrid improper ferroelectric coupling—although not always recognised as such—already present in the literature and we fully anticipate further examples will continue to emerge. Despite the fact that our analysis has been focussed on polarisation in formate perovskite analogues, the general rules developed here extend to all molecular perovskites and to all applications where inversion symmetry breaking is necessary. A recent example is the development of non-linear optics based on dicyanamide perovskite chemistry54.

Methods

Group theoretical analysis

A hypothetical aristotype molecular perovskite was employed as our model system, with the space group \(Pm\bar 3m\) and the (monoatomic) A-site cation at 1a (0, 0, 0), B-site cation at 2a \(\left( {\frac{1}{2},\,\frac{1}{2},\,\frac{1}{2}} \right)\), and X-site anion at 6f \(\left( {\frac{1}{2},\,\frac{1}{2},\,z} \right)\). The formula is thus AB(X2)3. This was used as an input to the web-based software ISODISTORT55, and the rigid-unit modes and orbital ordering patterns could be identified by inspection.

Multipoles may be classified as transforming as irreps of the rotational group SO(3). In the absence of any external perturbations to the rotational symmetry (i.e., a completely spherically symmetric crystal field), monopoles (angular component of s orbital) transform as a singly degenerate irrep, dipoles (p) as triply degenerate, quadrupoles (d) as 5-fold degenerate, etc. To determine the effect on the irreps of lowering the symmetry of SO(3), such as what occurs at any site symmetry in any crystallographic group, we can use descent of symmetry tables. For quadrupoles, if one or more of the irreps enters the symmetric representation (A1g), then we may consider the action of lowering the point group symmetry to have resulted in multipolar order (and this is how we define quadrupolar order in the context of this paper). In the aristotype ABX3 \(Pm\bar 3m\) structure, quadrupoles (i.e., d-orbitals) centred at A/B transform as E g and T2g while at X they transform as A1g, B1g, B2g, E g . Hence, the problem of determining whether a given irrep of space group \(Pm\bar 3m\) implies quadrupolar order is reduced to determining whether its action as a primary order parameter is sufficient to lower the point-group symmetry at A/B/X such that an additional quadrupole (degree of freedom) enters the totally symmetric representation.

In order to ensure that all relevant irreps for quadrupolar (or multipolar) orders were considered, a dummy atom was placed on 48n (x, y, z) in order to mimic electron density in the unit cell at the most general position. We use a setting where the A-site is located at the origin of the perovskite unit cell (see Supplementary Table 1 for conversion to the other setting). For each relevant point of the Brillouin zone, we test in turn the action of an order parameter transforming as one of these irreps, and list its effect on lowering the point group symmetry at A, B, and X, and hence the degree of quadrupolar order to which they correspond. We start by considering the Γ-point irreps, a process which corresponds to ascertaining the relationship between lattice strain and multipolar order. Next, we consider high-symmetry order parameter directions (OPDs) for the zone-boundary irreps which, where possible, we choose such that there are no secondary order parameters. This is important, since many primary order parameters transforming as zone-boundary irreps will imply a lattice strain and hence indirectly induce quadrupolar order at the Γ-point, but do not themselves correspond to such a ordering at the X/M/R-points. Where it is not possible to find a high-symmetry OPD with associated isotropy subgroup without secondary order parameters (SOPs), a process of elimination is used, subtracting the degree of quadrupolar ordering implied by each SOP in turn. In such a manner it was possible to identify unambiguously which irreps were associated with quadrupolar order.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).

References

Scott, J. F. Applications of modern ferroelectrics. Science 315, 954–959 (2007).

von Hippel, A., Breckenridge, R. G., Chesley, F. G. & Tisza, L. High dielectric constant ceramics. Ind. Eng. Chem. 38, 1097–1109 (1946).

Matthias, B. T. Ferroelectricity. Science 113, 591–596 (1951).

Cohen, R. E. Origin of ferroelectricity in perovskite oxides. Nature 358, 136–138 (1992).

Randall, C. A., Bhalla, A. S., Shrout, T. R. & Cross, L. E. Classification and consequences of complex lead perovskite ferroelectrics with regard to B-site cation order. J. Mater. Res. 5, 829–834 (1990).

Burdett, J. K. Use of the Jahn-Teller theorem in inorganic chemistry. Inorg. Chem. 20, 1959–1962 (1981).

Senn, M. S., Keen, D. A., Lucas, T. C. A., Hriljac, J. A. & Goodwin, A. L. Emergence of long-range order in BaTiO3 from local symmetry-breaking distortions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 207602 (2016).

Hill, N. A. Why are there so few magnetic ferroelectrics? J. Phys. Chem. B 104, 6694–6709 (2000).

Benedek, N. A. & Fennie, C. J. Why are there so few perovskite ferroelectrics? J. Phys. Chem. C 117, 13339–13349 (2013).

Benedek, N. A. & Fennie, C. J. Hybrid improper ferroelectricity: a mechanism for controllable polarization-magnetization coupling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 107204 (2011).

Hewat, A. W. Structure of rhombohedral ferroelectric barium titanate. Ferroelectrics 6, 215–218 (1974).

Benedek, N. A., Rondinelli, J. M., Djani, H., Ghosez, P. & Lightfoot, P. Understanding ferroelectricity in layered perovskites: new ideas and insights from theory and experiments. Dalton Trans. 44, 10543–10558 (2015).

Pitcher, M. J. et al. Tilt engineering of spontaneous polarization and magnetization above 300 K in a bulk layered perovskite. Science 347, 420–424 (2015).

Rondinelli, J. M., & Fennie, C. J. Octahedral rotation-induced ferroelectricity in cation ordered perovskites. Adv. Mater. 24, 1961–1968 (2012).

Oh, Y. S., Luo, X., Huang, F.-T., Wang, Y. & Cheong, S.-W. Experimental demonstration of hybrid improper ferroelectricity and the presence of abundant charged walls in (Ca,Sr)3Ti2O7 crystals. Nat. Mater. 14, 407–413 (2015).

Li, W. et al. Chemically diverse and multifunctional hybrid organic-inorganic perovskites. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 16099 (2017).

Weber, D. CH3NH3SnBr x I3−x (x = 0 − 3) - Sn(II)-system with cubic perovskite structure. Z. Naturforsch. B 33, 862–865 (1978).

Saparov, B. & Mitzi, D. B. Organic-inorganic perovskites: structural versatility for functional materials design. Chem. Rev. 116, 4558–4596 (2016).

Sletten, E. & Jensen, L. H. The crystal structure of dimethylammonium copper(II) formate, NH2(CH3)2[Cu(OOCH)3]. Acta Cryst. B 29, 1752–1756 (1973).

Jain, P., Dalal, N. S., Toby, B. H., Kroto, H. W. & Cheetham, A. K. Order-disorder antiferroelectric phase transition in a hybrid inorganic-organic framework with the perovskite architecture. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 10450–10451 (2008).

Xu, W.-J. et al. The cation-dependent structural phase transition and dielectric response in a family of cyano-bridged perovskite-like coordination polymers. Dalton Trans. 45, 4224–4229 (2016).

Buser, H. J., Schwarzenbach, D., Petter, W. & Ludi, A. The crystal structure of Prussian Blue: Fe4[Fe(CN)6]3·xH2O. Inorg. Chem. 16, 2704–2710 (1977).

Zhao, X.-H. et al. Cation-dependent magnetic ordering and room-temperature bistability in azido-bridged perovskite-type compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 16006–16009 (2013).

Du, Z.-Y. et al. Structural transition in the perovskite-like bimetallic azido coordination polymers (NMe4)2[B′·B″(N3)6] (B′ = Cr3+, Fe3+; B″ = Na+, K+). Cryst. Growth Des. 14, 3903–3909 (2014).

Schlueter, J. A., Manson, J. L., Hyzer, K. A. & Geiser, U. Spin canting in the 3D anionic dicyanamide structure (SPh3)Mn(dca)3 (Ph = phenyl, dca = dicyanamide). Inorg. Chem. 43, 4100–4102 (2004).

Tong, M.-L. et al. Cation-templated construction of three-dimensional α-Po cubic-type [M(dca)3] networks. Syntheses, structures and magnetic properties of A[M(dca)3] (dca = dicyanamide; for A = benzyltributylammonium, M = Mn2+, Co2+; for A = benzyltriethylammonium, M = Mn2+, Fe2+. New. J. Chem. 27, 779–782 (2003).

Wu, Y. et al. [Am]Mn(H2POO)3: a new family of hybrid perovskites based on the hypophosphite ligand. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 16999–17002 (2017).

Thiele, G. & Messer, D. S-Thiocyanato- und N-Isothiocyanato-Bindungsisomerie in den Kristallstrukturen von RbCd(SCN)3 und CsCd(SCN)3. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 464, 255–267 (1980).

Xie, K.-P. et al. Order-disorder phase transition in the first thiocyanate-bridged double perovskite-type coordination polymer: [NH4]2[NiCd(SCN)6]. CrystEngComm 18, 4495–4498 (2016).

Hill, J. A., Thompson, A. L. & Goodwin, A. L. Dicyanometallates as model extended frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 5886–5896 (2016).

Lefebvre, J., Chartrand, D. & Leznoff, D. B. Synthesis, structure and magnetic properties of 2-D and 3-D [cation]{M[Au(CN)2]3} (M = Ni, Co) coordination polymers. Polyhedron 26, 2189–2199 (2007).

Duyker, S. G., Hill, J. A., Howard, C. J. & Goodwin, A. L. Guest-activated forbidden tilts in a molecular perovskite analogue. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 11121–11123 (2016).

Boström, H. L. B., Hill, J. A. & Goodwin, A. L. Columnar shifts as symmetry-breaking degrees of freedom in molecular perovskites. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 31881–31894 (2016).

Zhang, W., Cai, Y., Xiong, R.-G., Yoshikawa, H. & Awaga, K. Exceptional dielectric phase transitions in a perovskite-type cage compound. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 6608–6610 (2010).

Evans, N. L. et al. Control of multipolar and orbital order in perovskite-like [C(NH2)3]Cu x Cd1−x(HCOO)3 metal–organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 9393–9396 (2016).

Goodwin, A. L. Rigid unit modes and intrinsic flexibility in linearly bridged framework structures. Phys. Rev. B 74, 134302 (2006).

Hammonds, K. D., Dove, M. T., Giddy, A. P., Heine, V. & Winkler, B. Rigid-unit phonon modes and structural phase transitions in framework silicates. Am. Mineral. 81, 1057–1079 (1996).

Dove, M. T., Heine, V. & Hammonds, K. D. Rigid unit modes in framework silicates. Mineral. Mag. 59, 629–639 (1995).

Huang, L.-F., Lu, X.-Z. & Rondinelli, J. M. Tunable negative thermal expansion in layered perovskites from quasi-two-dimensional vibrations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 115901 (2016).

Weller, M. T., Weber, O. J., Henry, P. F., Di Pumpo, A. M. & Hansen, T. C. Complete structure and cation orientation in the perovskite photovoltaic methylammonium lead iodide between 100 and 352 K. Chem. Commun. 51, 4180–4183 (2015).

Hatch, D. M. & Stokes, H. T. Invariants: program for obtaining a list of invariant polynomials of the order parameter components associated with irreducible representations of a space group. J. Appl. Cryst. 36, 951–952 (2003).

Antsyshkina, A. S., Porai Koshits, M. A., Ostrikova, V. N. & Sadikov, G. G. Stereochemistry of double formates. Crystal structure of ammonium triformatocadmate, (NH4)Cd(CHO2)3 and KCd(CHO2)3. Sov. J. Coord. Chem. 9, 855–858 (1983).

Gómez-Aguirre, L. C. et al. Room-temperature polar order in [NH4][Cd(HCOO)3]-a hybrid inorganic–organic compound with a unique perovskite architecture. Inorg. Chem. 54, 2109–2116 (2015).

Hu, K.-L., Kurmoo, M., Wang, Z. & Gao, S. Metal-organic perovskites: synthesis, structures, and magnetic properties of [C(NH2)3][MII(HCOO)3] (M = Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, and Zn; C(NH2)3 = Guanidinium). Chem. Eur. J. 15, 12050–12064 (2009).

Wang, Z. et al. Anionic NaCl-type frameworks of [MnII \(({\mathrm{HCOO}})_3^ -\)], templated by alkylammonium, exhibit weak ferromagnetism. Dalton Trans. 0, 2209–2216 (2004).

Wang, X.-Y., Gan, L., Zhang, S.-W. & Gao, S. Perovskite-like metal formates with weak ferromagnetism and as precursors to amorphous materials. Inorg. Chem. 43, 4615–4625 (2004).

Bovill, S. M. & Saines, P. J. Structure and magnetic properties of the AB(HCO2)3 (A = Rb+ or Cs+, B = Mn2+, Co2+ or Ni2+) frameworks: probing the effect of size on the phase evolution of the ternary formates. CrystEngComm 17, 8319–8326 (2015).

Collings, I. E. et al. Compositional dependence of anomalous thermal expansion in perovskite-like ABX3 formates. Dalton Trans. 45, 4169–4178 (2016).

Stroppa, A. et al. Electric control of magnetization and interplay between orbital ordering and ferroelectricity in a multiferroic metal-organic framework. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 5847–5850 (2011).

Stroppa, A., Barone, P., Jain, P., Perez-Mato, J. M. & Picozzi, S. Hybrid improper ferroelectricity in a multiferroic and magnetoelectric metal-organic framework. Adv. Mater. 25, 2284–2290 (2013).

Jona, F. & Shirane, G. Ferroelectric Crystals (Pergamon, Oxford, 1962).

Wang, B.-Q., Yan, H.-B., Huang, Z.-Q. & Zhang, Z. Reversible high-temperature phase transition of a manganese (II) formate framework with imidazolium cations. Acta Cryst. C 69, 616–619 (2013).

Lufaso, M. W. & Woodward, P. M. Prediction of the crystal structures of perovskites using the software program SPuDS. Acta Cryst. B 57, 725–738 (2001).

Geng, F.-J. et al. Perovskite-type organic-inorganic hybrid NLO switches tuned by guest cations. J. Mater. Chem. C. 5, 1529–1536 (2017).

Campbell, B. J., Stokes, H. T., Tanner, D. E. & Hatch, D. M. ISODISPLACE: a web-based tool for exploring structural distortions. J. Appl. Cryst. 39, 607–614 (2006).

Chen, S., Shang, R., Hu, K.-L., Wang, Z.-M. & Gao, S. [NH2NH3][M(HCOO)3] (M = Mn2+, Zn2+, Co2+ and Mg2+): structural phase transitions, prominent dielectric anomalies and negative thermal expansion, and magnetic ordering. Inorg. Chem. Front. 1, 83–98 (2014).

Acknowledgements

M.S.S. acknowledges the Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851 and the Royal Society for Fellowships. A.L.G. acknowledges the EPSRC (UK) and the ERC for support under grants EP/G004528/2 and 279705, respectively.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.L.B.B. and M.S.S. performed the symmetry analysis. M.S.S. and A.L.G. supervised the study. All authors designed the study and contributed to the writing of the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Boström, H.L.B., Senn, M.S. & Goodwin, A.L. Recipes for improper ferroelectricity in molecular perovskites. Nat Commun 9, 2380 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-04764-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-04764-x

This article is cited by

-

Ferroelectric order in hybrid organic-inorganic perovskite NH4PbI3 with non-polar molecules and small tolerance factor

npj Computational Materials (2023)

-

Polarization from sliding molecular rotors

Nature Materials (2022)

-

The chemistry and physics of organic—inorganic hybrid perovskite quantum wells

Science China Chemistry (2022)

-

Modulation on the electrical and optical properties of Na and Rh co-doped Ruddlesden-Popper layered Ca3Ti2O7

Journal of Electroceramics (2021)

-

Humidity sensor applications based on mesopores LaCoO3

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.