Abstract

When assessing spatially extended complex systems, one can rarely sample the states of all components. We show that this spatial subsampling typically leads to severe underestimation of the risk of instability in systems with propagating events. We derive a subsampling-invariant estimator, and demonstrate that it correctly infers the infectiousness of various diseases under subsampling, making it particularly useful in countries with unreliable case reports. In neuroscience, recordings are strongly limited by subsampling. Here, the subsampling-invariant estimator allows to revisit two prominent hypotheses about the brain’s collective spiking dynamics: asynchronous-irregular or critical. We identify consistently for rat, cat, and monkey a state that combines features of both and allows input to reverberate in the network for hundreds of milliseconds. Overall, owing to its ready applicability, the novel estimator paves the way to novel insight for the study of spatially extended dynamical systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

How can we infer properties of a high-dimensional dynamical system if we can only observe a very small part of it? This problem of spatial subsampling is common to almost every area of research where spatially extended, time evolving systems are investigated. For example, in many diseases the number of reported infections may be much lower than the unreported ones1, or in the financial system only a subset of all banks is evaluated when assessing the risk of developing system wide instability2 (“stress test”). Spatial subsampling is particularly severe when recording neuronal spiking activity, because the number of neurons that can be recorded with millisecond precision is vanishingly small compared to the number of all neurons in a brain area3,4,5.

Here, we show that subsampling leads to a strong overestimation of stability in a large class of time evolving systems, which include epidemic spread of infectious diseases6, cell proliferation, evolution (see ref. 7 and references therein), neutron processes in nuclear power reactors8, spread of bankruptcy9, evolution of stock prices10, or the propagation of spiking activity in neural networks11,12. However, correct risk prediction is essential to timely initiate counter actions to mitigate the propagation of events. We introduce a novel estimator that allows correct risk assessment even under strong subsampling. Mathematically, the evolution of all these systems is often approximated by a process with a 1st order autoregressive representation (PAR), e.g., by an AR(1), branching, or Kesten process. For these processes, we derive first the origin of the estimation bias and develop a novel estimator, which we analytically prove to be consistent under subsampling. We then apply the novel estimator to models and real-world data of disease and brain activity. To assure that a PAR is a reasonable approximation of the complex system under study, and to exclude contamination through potential non-stationarities, we included a set of automated, data-driven tests.

Results

In a PAR (Supplementary Notes 1–4), the activity in the next time step, At+1, depends linearly on the current activity A t . In addition, it incorporates external input, e.g., drive from stimuli or other brain areas, with a mean rate h, yielding the autoregressive representation

where 〈· | ·〉 denotes the conditional expectation. The stability of A t is solely governed by m, e.g., the mean number of persons infected by one diseased person13. The activity is stationary if m < 1, while it grows exponentially if m > 1. The state m = 1 separates the stable from the unstable regime. Especially close to this transition, a correct estimate of m is vital to assess the risk that A t develops a large, potentially devastating cascade or avalanche of events (e.g., an epidemic disease outbreak or an epileptic seizure), either generically or via a minor increase in m.

A conventional estimator14,15 \(\hat m_{\mathrm{C}}\) of m uses linear regression of activity at time t and t + 1, because the slope of linear regression directly returns m owing to the autoregressive representation in Eq. (1). This estimation of m is consistent if the full activity A t is known. However, under subsampling it can be strongly biased, as we show here. To derive the bias quantitatively, we model subsampling in a generic manner in our stochastic framework: we assume only that the subsampled activity a t is a random variable that in expectation it is proportional to A t , \(\left\langle {a_t|{\kern 1pt} A_t} \right\rangle = \alpha {\kern 1pt} A_t + \beta\) with two constants α and β (Supplementary Note 3). This represents, for example, sampling a fraction α of all neurons in a brain area. Then the conventional estimator is biased by m(α2Var[A t ]/Var[a t ] − 1) (Supplementary Corollary 6). The bias vanishes only when all units are sampled (α = 1, Fig. 1c–e), but is inherent to subsampling and cannot be overcome by obtaining longer recordings.

Spatial subsampling. a In complex networks, such as the brain, often only a small subset of all units can be sampled (spatial subsampling); figure created using TREES57. b In a branching network (BN), an active unit (e.g., a spiking neuron, infected individual, or defaulting bank) activates some of its neighbors in the next time step. Thereby activity can spread over the system. Units can also be activated by external drive. As the subsampled activity a t may significantly differ from the actual activity At, spatial subsampling can impair inferences about the dynamical properties of the full system. c In recurrent networks (BN, Bak-Tang-Wiesenfeld model (BTW)), the conventional estimator (empty symbols) substantially underestimates the branching ratio m when less units n are sampled, as theoretically predicted (dashed lines). The novel multistep regression (MR) estimator (full symbols) always returns the correct estimate, even when sampling only 10 or 1 out of all N = 104 units. d For a BN with m = 0.99, the conventional estimator infers \(\hat m\) = 0.37, \(\hat m\) = 0.1, or \(\hat m\) = 0.02 when sampling 100, 10, or 1 units, respectively. Kalman filtering based estimation returns approximately correct values under slight subsampling (n = 100), but is biased under strong subsampling. In contrast, MR estimation returns the correct \(\hat m_{}^{}\) for any subsampling. e MR estimation is exemplified for a subcritical branching process (m = 0.9, h = 10), where active units are observed with probability α. Under subsampling (gray), the regression slopes r1 are smaller than under full sampling (blue). f While conventional estimation of m relies on the linear regression r1 and is biased under subsampling, MR estimation infers \(\hat m\) from the exponential relation r k ∝ mk, which remains invariant under subsampling

Kalman filtering16,17,18, a state-of-the-art approach for system identification, cannot overcome the subsampling bias either, because it assumes Gaussian noise for both the evolution of A t and the sampling process for generating a t (Supplementary Note 7). These assumptions are violated under typical subsampling conditions, when the values of a t become too small, so that the central limit theorem is not applicable, and hence Kalman filtering fails (Fig. 1d). It is thus applicable to a much narrower set of subsampling problems and in addition requires orders of magnitude longer runtime compared to our novel estimator (Supplementary Fig. 7).

Our novel estimator takes a different approach than the other estimators (Supplementary Note 4). Instead of directly using the biased regression of activity at time t and t + 1, we perform multiple linear regressions of activity between times t and t + k with different time lags k = 1,…, kmax. These return a collection of linear regression slopes r k (note that r1 is simply the conventional estimator \(\hat m_{\mathrm{C}}\)). Under full sampling, one expects an exponential relation19 r k = mk (Supplementary Theorem 2). Under subsampling, however, we showed that all regressions slopes r k between a t and at+k are biased by the same factor b = α2Var[A t ]/Var[a t ] (Supplementary Theorem 5). Hence, the exponential relation generalizes to

under subsampling. The factor b is, in general, not known and thus m cannot be estimated from any r k alone. However, because b is constant, one does not need to know b to estimate \(\hat m_{}^{}\) from regressing the collection of slopes r k against the exponential model bmk according to Eq. (2). This result serves as the heart of our new multiple-regression (MR) estimator (Fig. 1f, Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2, Supplementary Corollary 3).

In fact, MR estimation is equivalent to estimating the autocorrelation time of subcritical PARs, where autocorrelation and regression r k are equal: we showed that subsampling decreases the autocorrelation strength r k , but the autocorrelation time τ is preserved. This is because the system itself evolves independently of the sampling process. While subsampling biases each regression r k by decreasing the mutual dependence between subsequent observations (a t , at+k), the temporal decay in r k ~ mk = e−kΔt/τ remains unaffected, allowing for a consistent estimate of m even when sampling only a single unit (Fig. 1d). Here, τ = −Δt/log m refers to the autocorrelation time of stationary (subcritical) processes, where autocorrelation and regression r k are equal, and Δt is the time scale of the investigated process. Particularly close to m = 1 the autocorrelation time τ = −Δt/log m diverges, which is known as critical slowing down20. Because of this divergence, MR estimation can resolve the distance to criticality in this regime with high precision. Making use of this result allows for a consistent estimate of m even when sampling only a single unit (Fig. 1d).

PARs are typically only a first order approximation of real world event propagation. However, their mathematical structure allowed for an analytical derivation of the subsampling bias and the consistent estimator. To show that the MR estimator returns correct results also for more complex systems, we applied it to more complex simulated systems: a branching network12 (BN) and the non-linear Bak–Tang–Wiesenfeld model21 (BTW, see Supplementary Note 8). In contrast to generic PARs, these models (a) run on recurrent networks and (b) are of finite size. In addition, the second model shows (c) completely deterministic propagation of activity instead of the stochastic propagation that characterizes PARs, and (d) the activity of each unit depends on many past time steps, not only one. Both models approximate neural activity propagation in cortex3,4,11,12,22,23. For both models the numerical estimates of m were precisely biased as analytically predicted, although the models are only approximated by a PAR (dashed lines in Fig. 1c, Supplementary Eq. (4)). The bias is considerable: for example, sampling 10% or 1% of the neurons in a BN with m = 0.9 resulted in the estimates \(\hat m_{\mathrm{C}}\) = r1 = 0.312, or even \(\hat m_{\mathrm{C}}\) = 0.047, respectively. Thus a process fairly close to instability (m = 0.9) is mistaken as Poisson-like (\(\hat m_{\mathrm{C}}\) = 0.047 ≈ 0) just because sampling is constrained to 1% of the units. Thereby the risk that systems may develop instabilities is severely underestimated.

MR estimation is readily applicable to subsampled data, because it only requires a sufficiently long time series a t , and the assumption that in expectation a t is proportional to A t . Hence, in general it suffices to sample the system randomly, without even knowing the system size N, the number of sampled units n, or any moments of the underlying process. Importantly, one can obtain a consistent estimate of m, even when sampling only a very small fraction of the system, under homogeneity even when sampling only one single unit (Fig. 1c, d, Supplementary Fig. 6). This robustness makes the estimator readily applicable to any system that can be approximated by a PAR. We demonstrate the bias of conventional estimation and the robustness of MR estimation at the example of two real-world applications.

Application to disease case reports

We used the MR estimator to infer the “reproductive number” m from incidence time series of different diseases24. Disease propagation represents a nonlinear, complex, real-world system often approximated by a PAR25,26. Here, m determines the disease spreading behavior and has been deployed to predict the risk of epidemic outbreaks6. However, the problem of subsampling or under-ascertainment has always posed a challenge1,27.

As a first step, we cross-validated the novel against the conventional estimator using the spread of measles in Germany, surveyed by the Robert-Koch-Institute (RKI). We chose this reference case, because we expected case reports to be almost fully sampled owing to the strict reporting policy supported by child care facilities and schools28,29, and to the clarity of symptoms. Indeed, the values for \(\hat m\) inferred with the conventional and with the novel estimator, coincided (Fig. 2d, Supplementary Note 9). In contrast, after applying artificial subsampling to the case reports, thereby mimicking that each infection was only diagnosed and reported with probability α < 1, the conventional estimator severely underestimated the spreading behavior, while MR estimation always returned consistent values (Fig. 2d). This shows that the MR estimator correctly infers the reproductive number m directly from subsampled time series, without the need to know the degree of under-ascertainment α.

Disease propagation. In epidemic models, the reproductive number m can serve as an indicator for the infectiousness of a disease within a population, and predict the risk of large incidence bursts. We have estimated \(\hat m_{}^{}\) from incidence time series of measles infections for 124 countries worldwide (Supplementary Note 9); as well as noroviral infection, measles, and invasive meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections in Germany. a MR estimation of \(\hat m\) is shown for measles infections in three different countries. Error bars here and in all following figures indicate 1SD or the corresponding 16 to 84% confidence intervals if asymmetric. The reproductive numbers \(\hat m\) decrease with the vaccination rate (Spearman rank correlation: r = −0.342, p < 10−4). b Weekly case report time series for norovirus, measles and MRSA in Germany. c Reproductive numbers \(\hat m\) for these infections. d When artificially subsampling the measles recording (under-ascertainment), conventional estimation underestimates \(\hat m_{\mathrm{C}}\), while MR estimation still returns the correct value. Both estimators return the same \(\hat m\) under full sampling

Second, we evaluated worldwide measles case and vaccination reports for 124 countries provided by the WHO since 1980 (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Note 9), because the vaccination percentage differs in each country, and this is expected to impact the spreading behavior through m. The reproductive numbers \(\hat m\) ranged between 0 and 0.93, and in line with our prediction clearly decreased with increasing vaccination percentage in the respective country (Spearman rank correlation: r = −0.342, p < 10−4).

Third, we estimated the reproductive numbers for three diseases in Germany with highly different infectiousness: noroviral infection27,30, measles, and invasive meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA, an antibiotic-resistant germ classically associated with health care facilities31, Fig. 2b, c), and quantified their propagation behavior. MR estimation returned the highest \(\hat m\) = 0.98 for norovirus, compliant with its high infectiousness32. For measles we found the intermediate \(\hat m\) = 0.88, reflecting the vaccination rate of about 97%. For MRSA we identified m = 0, confirming that transmission is still minor in Germany33. However, a future increase of transmission is feared and would pose a major public health risk34. Such an increase could be detected by our estimator, even in countries where case reports are incomplete.

Reverberating spiking activity in vivo

We applied the MR estimator to cortical spiking activity in vivo to investigate two contradictory hypotheses about collective spiking dynamics. One hypothesis suggests that the collective dynamics is “asynchronous irregular” (AI)35,36,37,38, i.e., neurons spike independently of each other and in a Poisson manner (m = 0), which may reflect a balanced state39,40,41. The other hypothesis suggests that neuronal networks operate at criticality (m = 1)3,11,42,43,44, thus in a particularly sensitive state close to a phase transition. These different hypotheses have distinct implications for the coding strategy of the brain: Criticality is characterized by long-range correlations in space and time, and in models optimizes performance in tasks that profit from long reverberation of the activity in the network12,45,46,47,48. In contrast, the typical balanced state minimizes redundancy49 and supports fast network responses39.

Analyzing in vivo spiking activity from Macaque monkey prefrontal cortex during a memory task, anesthetized cat visual cortex with no stimulus (Fig. 3a, b), and rat hippocampus during a foraging task (Supplementary Note 10) returned \(\hat m\) to be between 0.963 and 0.998 (median \(\hat m\) = 0.984, Fig. 3e, Supplementary Fig. 5), corresponding to autocorrelation times between 100 and 2000 ms. This clearly suggests that spiking activity in vivo is neither AI-like (m = 0), nor consistent with a critical state (m = 1), but in a reverberating state that shows autocorrelation times of a few hundred milliseconds. We call the range of the dynamical states found in vivo reverberating, because input reverberates for a few hundred millisecond in the network, and therefore enables integration of information50,51,52. Thereby the reverberating state constitutes a specific narrow window between AI state, where perturbations of the firing rate are quenched immediately, and the critical state, in which perturbations can in principle persist infinitely long (for more details, see Wilting and Priesemann53).

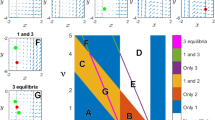

Animal spiking activity in vivo. In neuroscience, m denotes the mean number of spikes triggered by one spike. We estimated \(\hat m\) from spiking activity recorded in vivo in monkey prefrontal cortex, cat visual cortex, and rat hippocampus. a Raster spike plot and population rate at of 50 single units illustrated for cat visual cortex. b MR estimation based on the exponential decay of the autocorrelation r k of a t . Inset: Comparison of conventional and MR estimation results for single units (medians \(\hat m_{\mathrm{C}}\) = 0.057 and \(\hat m\) = 0.954, respectively). c \(\hat m\) estimated from further subsampled cat recordings, estimated with the conventional and MR estimator. Error bars indicate variability over 50 randomly subsampled n out of the recorded 50 channels. d Avalanche size distributions for cat visual cortex (blue) and the networks with AI, reverberating and near-critical dynamics in f. e For all simulations, MR estimation returned the correct distance to instability (criticality) \(\epsilon\) = 1 − m (Supplementary Note 8). In vivo spike recordings from rat, cat, and monkey, clearly differed from critical (\(\epsilon\) = 0) and AI (\(\epsilon\) = 1) states (median \(\hat m\) = 0.98, error bars: 16 to 84% confidence intervals, note that some confidence intervals are too small to be resolved). Opaque symbols indicate that MR estimation was rejected (Supplementary Fig. 5, Supplementary Note 5). Green, red, and yellow arrows indicate \(\epsilon\) for the dynamic states shown in f. f Population activity and raster plots for AI activity, reverberating, and near critical networks. All three networks match the recording from cat visual cortex with respect to number of recorded neurons and mean firing rate

We demonstrate the robustness to subsampling for the activity in cat visual cortex: we chose random subsets of n neurons from the total of 50 recorded single units. For any subset, even for single neurons, MR estimation returned about the same median \(\hat m\) (Fig. 3c). In contrast, the conventional estimator misclassified neuronal activity by strongly underestimating \(\hat m\): instead of \(\hat m\) = 0.984, it returned \(\hat m_{\mathrm{C}}\) = 0.271 for the activity of all 50 neurons. This underestimation gets even more severe when considering stronger subsampling (n < 50, Fig. 3c). Ultimately, for single neuron activity, the conventional estimator returned \(\hat m_{\mathrm{C}}\) = 0.057 ≈ 0, which would spuriously indicate dynamics close to AI instead of the reverberating state (inset of Fig. 3b, c and Supplementary Fig. 6). The underestimation of \(\hat m_{\mathrm{C}}\) was present in all experimental recordings (r1 in Supplementary Fig. 5).

On first sight, \(\hat m\) = 0.984 may appear close to the critical state, particularly as physiologically a 1.6% difference to m = 1 is small in terms of the effective synaptic strength. However, this seemingly small difference in single unit properties has a large impact on the collective dynamics and makes AI, reverberating, and critical states clearly distinct. This distinction is readily manifest in the fluctuations of the population activity (Fig. 3f). Furthermore, the distributions of avalanche sizes clearly differ from the power-law scaling expected for critical systems11, but are well captured by a matched, reverberating model (Fig. 3d). Because of the large difference in the network dynamics, the MR estimator can distinguish AI, reverberating, and critical states with the necessary precision. In fact, the estimator would allow for 100 times higher precision when distinguishing critical from non-critical states, assuming in vivo-like subsampling and mean firing rate (sampling n = 100 from N = 104 neurons, Fig. 3e). With larger N, this discrimination becomes even more sensitive (detailed error estimates: Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Note 6). As the number of neurons in a given brain area is typically much higher than N = 104 in the simulation, finite size effects are not likely to account for the observed deviation from criticality \(\epsilon\) = 1 − m ≈ 10−2 in vivo, supporting that in rat, cat, and monkey the brain does not operate in a critical state. Still, additional factors like input or refractory periods may limit the maximum attainable m to quasi-critical dynamics on a Widom line54, which could in principle conform with our results.

Discussion

Most real-world systems, including disease propagation or cortical dynamics, are more complicated than a simple PAR. For cortical dynamics, for example, heterogeneity of neuronal morphology and function, non-trivial network topology, and the complexity of neurons themselves are likely to have a profound impact onto the population dynamics55. In order to test for the applicability of a PAR approximation, we defined a set of conservative tests (Supplementary Note 5 and Supplementary Table 1) and included only those time series, where the approximation by a PAR was considered appropriate. For example, we excluded all recordings that showed an offset in the slopes r k , because this offset is, strictly speaking, not explained by a PAR and might indicate non-stationarities (Supplementary Fig. 3). Even with these conservative tests, we found the exponential relation r k = bmk expected for PARs in the majority of real-world time series (Supplementary Fig. 5, Supplementary Note 9). This shows that a PAR is a reasonable approximation for dynamics as complex as cortical activity or disease propagation. With using PARs, we draw on the powerful advantage of analytical tractability, which allowed for valuable insight into dynamics and stability of the respective system. It is then a logical next step to refine the model by including additional relevant parameters56. However, the increasing richness of detail typically comes at the expense of analytical tractability.

By employing for the first time a consistent, quantitative estimation, we provided evidence that in vivo spiking population dynamics reflects a stable, fading reverberation state around m = 0.98 universally across different species, brain areas, and cognitive states. Because of its broad applicability, we expect that besides the questions investigated here, MR estimation can substantially contribute to the understanding of real-world dynamical systems in diverse fields of research where subsampling prevails.

Data availability

Time series with yearly case reports for measles in 194 different countries are available online from the World Health Organization (WHO) for the years between 1980 and 2014. Weekly case reports for measles, norovirus, and invasive meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Germany are available through their SURVSTAT@RKI server of the Robert-Koch-Institute. The data from rat hippocampus (https://doi.org/10.6080/K0Z60KZ9) and cat visual cortex (https://doi.org/10.6080/K0MW2F2J) are available from the CRCNS.org database. Python code for basic MR estimation and branching process simulation is available from github (https://github.com/jwilting/WiltingPriesemann2018). Any additional code is available from the authors upon request.

References

Papoz, L., Balkau, B. & Lellouch, J. Case counting in epidemiology: limitations of methods based on multiple data sources. Int. J. Epidemiol. 25, 474–478 (1996).

Quagliariello, M. Stress-testing the banking system: methodologies and applications. (Cambridge University Press, NY, 2009).

Priesemann, V., Munk, M. H. J. & Wibral, M. Subsampling effects in neuronal avalanche distributions recorded in vivo. BMC Neurosci. 10, 40 (2009).

Ribeiro, T. L. et al. Spike avalanches exhibit universal dynamics across the sleep-wake cycle. PLoS ONE 5, e14129 (2010).

Ribeiro, T. L. et al. Undersampled critical branching processes on small-world and random networks fail to reproduce the statistics of spike avalanches. PLoS ONE 9, e94992 (2014).

Farrington, C. P., Kanaan, M. N. & Gay, N. J. Branching process models for surveillance of infectious diseases controlled by mass vaccination. Biostatistics 4, 279–295 (2003).

Kimmel, M. & Axelrod, D. E. Branching processes in biology, interdisciplinary applied mathematics 19 (Springer New York, NY, 2015).

Pazy, A. & Rabinowitz, P. On a branching process in neutron transport theory. Arch. Ration. Mech. Anal. 51, 153–164 (1973).

Filimonov, V. & Sornette, D. Quantifying reflexivity in financial markets: toward a prediction of flash crashes. Phys. Rev. E 85, 056108 (2012).

Mitov, G. K., Rachev, S. T., Kim, Y. S. & Fabozzi, F. J. Barrier option pricing by branching processes. Int. J. Theor. Appl. Financ. 12, 1055–1073 (2009).

Beggs, J. M. & Plenz, D. Neuronal avalanches in neocortical circuits. J. Neurosci. 23, 11167–11177 (2003).

Haldeman, C. & Beggs, J. Critical branching captures activity in living neural networks and maximizes the number of metastable states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 058101 (2005).

Heathcote, C. R. A branching process allowing immigration. J. R. Stat. Soc. B 27, 138–143 (1965).

Heyde, C. C. & Seneta, E. Estimation theory for growth and immigration rates in a multiplicative process. J. Appl. Probab. 9, 235 (1972).

Wei, C. & Winnicki, J. Estimation of the means in the branching process with immigration. Ann. Stat. 18, 1757–1773 (1990).

Hamilton, J. D. Time series analysis 2 (Princeton university press, Princeton, 1994).

Shumway, R. H. & Stoffer, D. S. An approach to time series smoothing and forecasting using the EM algorithm. J. Time Ser. Anal. 3, 253–264 (1982).

Ghahramani, Z. & Hinton, G. E. Parameter estimation for linear dynamical systems. Technical Report (University of Toronto, 1996).

Statman, A. et al. Synaptic size dynamics as an effectively stochastic process. PLoS Comput. Biol. 10, e1003846 (2014).

Scheffer, M. et al. Anticipating critical transitions. Science 338, 344–348 (2012).

Bak, P., Tang, C. & Wiesenfeld, K. Self-organized criticality: an explanation of the 1/f noise. Phys. Rev. Lett. 59, 381–384 (1987).

Priesemann, V., Valderrama, M., Wibral, M. & Le Van Quyen, M. Neuronal avalanches differ from wakefulness to deep sleep-evidence from intracranial depth recordings in humans. PLoS Comput. Biol. 9, e1002985 (2013).

Priesemann, V. et al. Spike avalanches in vivo suggest a driven, slightly subcritical brain state. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 8, 108 (2014).

Diekmann, O., Heesterbeek, J. A. P. & Metz, J. A. J. On the definition and the computation of the basic reproduction ratio R0 in models for infectious diseases in heterogeneous populations. J. Math. Biol. 28, 365–382 (1990).

Earn, D. J. A simple model for complex dynamical transitions in epidemics. Science 287, 667–670 (2000).

Brockmann, D., Hufnagel, L. & Geisel, T. The scaling laws of human travel. Nature 439, 462–465 (2006).

Hauri, A. M. et al. Electronic outbreak surveillance in germany: a first evaluation for nosocomial norovirus outbreaks. PLoS ONE 6, e17341 (2011).

Hellenbrand, W. et al. Progress toward measles elimination in Germany. J. Infect. Dis. 187, S208–S216 (2003).

Wichmann, O. et al. Further efforts needed to achieve measles elimination in Germany: results of an outbreak investigation. Bull. World Health Organ. 87, 108–115 (2009).

Bernard, H., Werber, D. & Höhle, M. Estimating the under-reporting of norovirus illness in Germany utilizing enhanced awareness of diarrhoea during a large outbreak of Shiga toxin-producing E. coli O104:H4 in 2011 a time series analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 14, 1–6 (2014).

Boucher, H. W. & Corey, G. R. Epidemiology of methicillin–resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Infect. Dis. 46, S344–S349 (2008).

Teunis, P. F. et al. Norwalk virus: how infectious is it? J. Med. Virol. 80, 1468–1476 (2008).

Köck, R. et al. The epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in Germany. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 108, 761–767 (2011).

DeLeo, F. R., Otto, M., Kreiswirth, B. N. & Chambers, H. F. Community-associated meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet 375, 1557–1568 (2010).

Burns, B. D. & Webb, A. C. The spontaneous activity of neurones in the cat’s cerebral cortex. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 194, 211–223 (1976).

Softky, W. R. & Koch, C. The highly irregular firing of cortical cells is inconsistent with temporal integration of random EPSPs. J. Neurosci. 13, 334–350 (1993).

de Ruyter van Steveninck, R. R. et al. Reproducibility and variability in neural spike trains. Science 275, 1805–1808 (1997).

Ecker, A. S. et al. Decorrelated neuronal firing in cortical microcircuits. Science 327, 584–587 (2010).

Vreeswijk, Cv & Sompolinsky, H. Chaos in neuronal networks with balanced excitatory and inhibitory activity. Science 274, 1724–1726 (1996).

Brunel, N. Dynamics of networks of randomly connected excitatory and inhibitory spiking neurons. J. Physiol. Paris 94, 445–463 (2000).

Renart, A. et al. The asynchronous state in cortical circuits. Science 327, 587–590 (2010).

Chialvo, D. R. Emergent complex neural dynamics. Nat. Phys. 6, 744–750 (2010).

Tkačik, G. et al. Thermodynamics and signatures of criticality in a network of neurons. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 11508–11513 (2015).

Humplik, J. & Tkačik, G. Probabilistic models for neural populations that naturally capture global coupling and criticality. PLoS Comput. Biol. 13, 1–26 (2017).

Kinouchi, O. & Copelli, M. Optimal dynamical range of excitable networks at criticality. Nat. Phys. 2, 348–351 (2006).

Boedecker, J. et al. Information processing in echo state networks at the edge of chaos. Theory Biosci. 131, 205–213 (2012).

Shew, W. L. & Plenz, D. The functional benefits of criticality in the cortex. Neuroscientist 19, 88–100 (2013).

Del Papa, B., Priesemann, V. & Triesch, J. Criticality meets learning: criticality signatures in a self-organizing recurrent neural network. PLoS One 12, 1–22 (2017).

Hyvärinen, A. & Oja, E. Independent component analysis: algorithms and applications. Neural Netw. 13, 411–430 (2000).

Murray, J. D. et al. A hierarchy of intrinsic timescales across primate cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 17, 1661–1663 (2014).

Chaudhuri, R. et al. A large-scale circuit mechanism for hierarchical dynamical processing in the primate cortex. Neuron 88, 419–431 (2015).

Jaeger, H. & Haas, H. Harnessing nonlinearity: predicting chaotic systems and saving energy in wireless communication. Science 304, 78–80 (2004).

Wilting, J. & Priesemann, V. On the ground state of spiking network activity in mammalian cortex. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1804.07864 (2018).

Williams-García, R. V., Moore, M., Beggs, J. M. & Ortiz, G. Quasicritical brain dynamics on a nonequilibrium Widom line. Phys. Rev. E 90, 062714 (2014).

Marom, S. Neural timescales or lack thereof. Prog. Neurobiol. 90, 16–28 (2010).

Eckmann, J. P. et al. The physics of living neural networks. Phys. Rep. 449, 54–76 (2007).

Cuntz, H., Forstner, F., Borst, A. & Häusser, M. One rule to grow them all: a general theory of neuronal branching and its practical application. PLoS Comput. Biol. 6, e1000877 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We thank Matthias Munk for sharing his data. J.W. received support from the Gertrud-Reemstma-Stiftung. V.P. received financial support from the German Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF) via the Bernstein Center for Computational Neuroscience (BCCN) Göttingen under Grant No. 01GQ1005B, and by the German-Israel-Foundation (GIF) under grant number G-2391-421.13. J.W. and V.P. received financial support from the Max Planck Society.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.W. and V.P. contributed equally.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wilting, J., Priesemann, V. Inferring collective dynamical states from widely unobserved systems. Nat Commun 9, 2325 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-04725-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-04725-4

This article is cited by

-

Sleep restores an optimal computational regime in cortical networks

Nature Neuroscience (2024)

-

Robust encoding of natural stimuli by neuronal response sequences in monkey visual cortex

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Residual dynamics resolves recurrent contributions to neural computation

Nature Neuroscience (2023)

-

Critical dynamics arise during structured information presentation within embodied in vitro neuronal networks

Nature Communications (2023)

-

A flexible Bayesian framework for unbiased estimation of timescales

Nature Computational Science (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.