Abstract

The standard model of cosmology predicts the existence of cosmic neutrino background in the present Universe. To detect cosmic relic neutrinos in the vicinity of the Earth, it is necessary to evaluate the gravitational clustering effects on relic neutrinos in the Milky Way. Here we introduce a reweighting technique in the N-one-body simulation method, so that a single simulation can yield neutrino density profiles for different neutrino masses and phase space distributions. In light of current experimental results that favor small neutrino masses, the neutrino number density contrast around the Earth is found to be almost proportional to the square of neutrino mass. The density contrast-mass relation and the reweighting technique are useful for studying the phenomenology associated with the future detection of the cosmic neutrino background.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The standard model of cosmology predicts that neutrinos were decoupled from the thermal bath when the temperature of the Universe was about 1 MeV. These relic neutrinos constitute the current cosmic neutrino background. Detecting cosmic relic neutrinos1, as proposed in the upcoming PTOLEMY experiment2, is thus a direct test of the standard model of cosmology, and can push our understanding of the Universe to its age of about one second. In order to detect them in the neighborhood of the Earth, a prerequisite would be to figure out the number density of relic neutrinos at our local environment. Although the standard model of cosmology does predict that the average number density of relic neutrinos in the current Universe is about 56 cm−3 for each flavor3, more relic neutrinos can be accreted around the Earth, due to the fact that massive neutrinos suffer from the gravitational potential of both dark matter (DM) and baryonic matter in the Milky Way (MW). Investigating the gravitational clustering of relic neutrinos is thus a necessary step towards interpreting the results from the future detection of cosmic neutrino background.

Gravitational clustering effects are often studied numerically with the N-body simulation method. However, to reach a resolution of ~8 kpc, the distance from the Earth to the galactic center of the MW, the N-body simulation turns out to be computationally expensive4. In 2004, a restricted but effective method called N-one-body simulation was proposed to evaluate the gravitational clustering effects of relic neutrinos5. In contrast with the N-body simulation, where all the interactions among particles are included, relic neutrinos in the N-one-body simulation are assumed to evolve under the gravitational potential of both DM and baryonic matter. The back reaction, i.e., the gravitational effects of neutrinos on the clustering of DM and baryonic matter, and the gravitational interactions among neutrinos are both considered to be negligible5,6. This assumption works for the evolution of the Universe at a late stage (z ≲ 3 with z being the redshift), when the energy density of neutrinos is much smaller than that of DM3. To implement the N-one-body simulation, one first divides the initial phase space of neutrinos into N-independent chunks, and then evolves each chunk following a one-body motion in the gravitational potential generated by DM and baryonic matter. Assembling all the N chunks with their corresponding weights after the evolution yields the final phase space distribution of neutrinos.

In this work we introduce a reweighting technique in the N-one-body simulation, so that a single N-one-body simulation is sufficient to yield neutrino density profiles for different neutrino masses and phase space distributions. For small neutrino masses, we find that the neutrino number density contrast is almost proportional to the square of neutrino mass. The dependence of gravitational clustering effects on the phase space distribution is also investigated, followed by the implications of gravitational clustering effects on interpreting the results from the future detection of cosmic neutrino background.

Results

Normalized evolution equations

Here we adopt a generalized Navarro–Frenk–White (NFW) profile7 for the DM distribution in the MW, while for the baryonic matter distribution a spherically symmetric profile is also assumed for simplicity8. See the Methods section for the details about the matter density profiles used in the numerical simulation.

Within the spherical gravitational potential ϕ(r), the one-body motion of a test particle with the mass m ν is confined to a plane, and obeys the following Hamiltonian equations9

where a = 1/(1 + z) is the scale factor of the Universe, τ is the conformal time defined as dτ = dt/a(t), and \(p_r = am_\nu \dot r\) and \(\ell = am_\nu r^2\dot \theta\) are the canonical momenta conjugate to r and θ, respectively. Here the dot denotes the derivative with respect to τ, and (r, θ) are the polar coordinates in the comoving frame. The gravitational potential ϕ(r, τ) also evolves and its evolution is assumed to be independent of relic neutrinos in the N-one-body simulation. Because of spherical symmetry, \(\ell\) is a conserved quantity and we may ignore the motion in the θ direction. A key observation in developing the reweighting technique is to identify that the evolution equations in Eq. (1) can be written in a form independent of the neutrino mass m ν . Namely, with the normalized quantities \(u_r \equiv p_r{\mathrm{/}}m_\nu = a\dot r\) and \(u_\theta \equiv \ell {\mathrm{/}}m_\nu = ar^2\dot \theta\), the following normalized evolution equations can be derived5

These normalized evolution equations are the ones implemented in our N-one-body simulation.

Reweighting technique

The essence of the reweighting technique is to let a test particle represent all the particles within a fixed interval (r a , ur,a, uθ,a) → (r b , ur,b, uθ,b) in the space spanned by (r, u r , u θ ). The size of the interval does not depend on the mass or the phase space distribution of relic neutrinos. The dependences on these quantities arise when associating weight to the fixed interval (r a , ur,a, uθ,a) → (r b , ur,b, uθ,b). To illustrate that, we first introduce another variable set of (r, y, ψ), with y = p/Tν,0. Here p denotes the magnitude of the canonical momentum, ψ is the direction of momentum with respect to the positive radial direction, and Tν,0 is the neutrino temperature at the present time. The transformations between (u r , u θ ) and (y, ψ) are given by \(\psi = {\mathrm{tan}}^{ - 1}\left( {ru_r{\mathrm{/}}u_\theta } \right)\) and y = m ν u r /(cosψTν,0). Therefore, the fixed interval (r a , ur,a, uθ,a) → (r b , ur,b, uθ,b) corresponds to an interval (r a , y a , ψ a ) → (r b , y b , ψ b ), which will have varying lower limit (y a ) and upper limit (y b ) depending on the neutrino mass m ν . For the phase space interval (r a , y a , ψ a ) → (r b , y b , ψ b ), we obtain its associated weight dw as follows5

where spherical symmetry is applied, and f(y) is the phase space distribution function. In the case of thermal relic neutrinos, f(y) follows the Fermi–Dirac form

The effect of neutrino masses reflects then in the lower and upper limits of y for a fixed interval in terms of (r, u r , u θ ), while for different phase space distributions one simply uses the corresponding forms of f(y).

In practice, one still needs to perform a benchmark simulation with definite neutrino mass and phase space distribution. This benchmark simulation serves two purposes. First, the one-body evolutions of N test particles can be obtained. Second, in the benchmark simulation the initial phase space of relic neutrinos is discretized, and such a discretization would fix the interval (r a , ur,a, uθ,a) → (r b , ur,b, uθ,b) for each evolved sample. When switching to another neutrino mass or a different phase space distribution, on one hand we can reuse those one-body evolution results from the benchmark simulation, and on the other hand we can associate a new weight to each evolved sample according to Eq. (3). With this reweighting technique, we then do not need to rerun the N-one-body simulation for different neutrino masses and phase space distributions, so that lots of computing time can be saved.

Thermal relic neutrinos

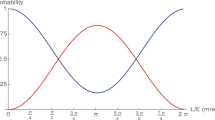

In this work we consider a benchmark N-one-body simulation with m ν = 0.15 eV and thermal Fermi–Dirac phase space distribution. See the Methods section for the details about this benchmark simulation. The reweighting technique then enables us to obtain neutrino densitiy profiles n ν (r) for other neutrino masses and phase space distributions. Consider the thermal phase space distribution first. In Fig. 1a, we show the neutrino density contrast δ ν , defined as \(\delta _\nu \equiv n_\nu {\mathrm{/}}\bar n_\nu - 1\) with \(\bar n_\nu\) being the average neutrino number density (δ ν corresponds to fc − 1 in ref. 8), as a function of the distance r to the galactic center of MW. The results of four different neutrino masses are shown, and the neutrino halos can extend up to a few mega parsecs. At the location of the Earth (r⊕ = 8 kpc) the neutrino density is enhanced by about 10% (115%) for the case of m ν = 0.05 (0.15) eV, due to the gravitational clustering effects.

Clustering of thermal relic neutrinos in the MW. a The neutrino contrast \(\delta _\nu = n_\nu {\mathrm{/}}\overline n _\nu - 1\) as a function of the distance r to the galactic center of MW. The location of the Earth r⊕ = 8 kpc is indicated by a gray vertical line. b The neutrino contrast δ ν as a function of the neutrino mass m ν for three different distances of r to the galactic center of MW. Both the horizontal and vertical axes are in logarithmic scale. Scatter points are the N-one-body simulation results. Each set of scatter points is well fitted by a power-law function \(\delta _\nu \propto m_\nu ^\gamma\)

For a fixed distance r, the relationship between the neutrino density contrast δ ν and m ν is displayed in Fig. 1b. We observe that for the three different distances of r, all the scatter points obtained from the N-one-body simulation can be well fitted by a power-law function of \(\delta _\nu \propto m_\nu ^\gamma\). The obtained exponents γ are around two for all cases, indicating that the linear approximation5,6 is appropriate in light of current cosmological constraints that favor small neutrino masses10. Recall that in the Vlasov equation9 for the phase space distribution function there exists a term involving both the gravitational potential ϕ and the distribution function f. In the linear approximation, one approximates the distribution function f in that term with the corresponding distribution function f0 without the presence of gravitational potential, so that the modified Vlasov equation becomes linear in both ϕ and f. The underlying requirement for making the linear approximation is that the perturbed distribution function f should be close to the unperturbed one f0, or the neutrino density contrast does not exceed greatly over order unity. For the neutrino masses considered in this work, according to Fig. 1 we find that the gravitational clustering effects are moderate so that the linear approximation works well here. However, if larger neutrino masses or heavier halo masses were considered, because of more enhanced gravitational clustering effects, the linear approximation would no longer be applicable, and the resulting power-law indices could have large deviations from two5.

At the location of the Earth, the fitted power-law function for thermal relic neutrinos is given by

A similar power-law function11 was obtained for higher neutrino masses m ν ∈ [0.15, 0.6] eV, by fitting previous N-one-body simulation results5. In the recent literature two benchmark values of m ν = 0.06 eV and 0.15 eV are also studied8. Since the adopted DM and baryonic matter profiles in this work are the same as those in ref. 8, we can directly compare our results with those in ref. 8. After taking into account the uncertainties from discrete sampling, we find that both results agree with each other, validating the reweighting technique. With the above fitted relation we can obtain neutrino number densities for all neutrinos within the mass range of [0.04, 0.15] eV. For m ν < 0.04 eV, the clustering effects due to the gravitational potential of baryonic matter and DM in the MW are insignificant, namely, the neutrino density contrast is less than about 0.05 at the location of the Earth. As a result, other astrophysical uncertainties, such as the contribution from the Virgo cluster8,12, may play more important role in predicting the local neutrino number densities. Furthermore, when m ν < 0.04 eV, the required energy resolution Δ (full width at half maximum of the Gaussian distribution) is estimated to be Δ ≃ 0.7m ν < 0.03 eV13, which is beyond the reach of the current proposal of the PTOLEMY experiment2. For these reasons, we choose not to consider the neutrino masses below 0.04 eV here.

New physics scenarios with non-thermal relic neutrinos

It is also interesting to consider new physics (NP) scenarios, in which some chiral states of neutrinos in the early Universe are non-thermal and possess a phase space distribution that is significantly deviated from the thermal Fermi–Dirac distribution. For illustration, we consider a fully degenerate phase space distribution14,

where y0 = 1.76 ensures the same average neutrino density as the thermal case. With the reweighting technique, we can also obtain the neutrino density profiles for this non-thermal case from the benchmark simulation. From Fig. 2, we observe that the neutrino contrast δ ν is about twice of that in the thermal case when m ν ≲ 0.1 eV. This is due to the fact that in the fully degenerate case more relic neutrinos reside in the low momentum states. For a given distance r, the relationship between δ ν and m ν can also be well described by a power-law function. The obtained exponents γ are also around two, so that the linear approximation5,6 can be applied to this fully degenerate case as well.

Clustering of fully degenerate relic neutrinos in the MW. The descriptions of a, b are the same as those in Fig. 1

Implications on the direct detection of relic neutrinos

Finally, we discuss the impact of gravitational clustering effects on the direct detection of relic neutrinos in the vicinity of the Earth. For concreteness, we take the PTOLEMY proposal as an example. In the PTOLEMY proposal, relic neutrinos are captured by the beta-decaying tritium nuclei 3H via the process νe + 3H → 3He + e−, and in the electron energy spetrum the signal events appear at a location that is 2m ν away from the beta-decay end point (assuming three degenerate neutrino masses). Although there exist many experimental issues13,15, such as the limited energy resolution and the large background from beta decay, we here only discuss the overall capture rate, assuming a total mass of tritium of 100 grams as given in the PTOLEMY proposal (see the Methods section for the details on calculating the capture rate). Since the capture rate depends on the nature of neutrinos and the underlying assumptions on the thermal history of neutrinos, we here focus on the case of Dirac neutrinos and discuss three typical physics scenarios. Note that in the following discussions the left(right)-handed chiral states of neutrinos also mean the right(left)-handed chiral states of anti-neutrinos.

The Standard Case refers to the scenario predicted by the standard model of cosmology, i.e., only the left-handed chiral states of neutrinos were thermally produced in the early Universe, while for the right-handed chiral states of neutrinos their interactions with the particles in the thermal bath were so weak that their abundances can be safely neglected.

In the first NP scenario, i.e., NP Case I, the left-handed chiral states of neutrinos have the same thermal history as Standard Case. However, because of some NP effects, the right-handed chiral states of neutrinos can also be thermally produced in the early Universe15,16, except for a higher decoupling temperature depending on the current cosmological constraints. Considering the current constraint on the extra effective number of neutrino species ΔNeff < 0.53 at the 95% confidence level (C.L.) by combining the Planck TT + lowP + BAO data sets with the helium abundance measurements10, the number density of the right-handed chiral states is found to be at most 28% of that of the left-handed chiral states15. For illustration, we here set the number density of the right-handed chiral states to be 28% of that of the left-handed chiral states, when neutrinos began free-streaming.

The second NP scenario, i.e., NP Case II, is almost the same as NP Case I, except that the right-handed chiral states are non-thermal and their phase space distribution is assumed to be the fully-degenerate form14. To satisfy the same cosmological constraint as NP Case I, their number density can be 52% of that of the left-handed chiral states17, when neutrinos began free-streaming.

In Fig. 3a we show the capture rate Γ as a function of the total neutrino mass \({\sum} {\kern 1pt} m_\nu\) ≡ m1 + m2 + m3 in Standard Case. Here m i ’s (for i = 1, 2, 3) are the three neutrino masses. The best-fit values of neutrino oscillation parameters from the latest global fit results18 are adopted, and two neutrino mass hierarchies, normal hierarchy (NH) (m1 < m2 < m3) and inverted hierarchy (IH) (m3 < m1 < m2), are distinguished. Because of gravitational clustering effects, we find that if taking \({\sum} {\kern 1pt} m_\nu\) = 0.23 eV, the 95% C.L. upper limit allowed by the Planck TT + lowP + lensing + BAO + JLA + H0 data sets10, the capture rate can be enhanced by about 23% (31%) in the case of NH (IH), compared to the scenario without clustering. Because of the low target mass of tritium nuclei, distinguishing the neutrino mass hierarchies via the direct detection of relic neutrinos, given the current specifications of the PTOLEMY proposal2, will be difficult. The capture rates in the NP Case I and II scenarios are given in Fig. 3b. Taking \({\sum} {\kern 1pt} m_\nu\) = 0.23 eV, the enhancement of capture rate due to gravitational clustering effects in NP Case I is the same as that in Standard Case, since in the two scenarios both the left-handed and right-handed chiral states of neutrinos possess the same thermal Fermi–Dirac phase space distribution. However, in NP Case II we find that the rate of enhancement turns out to be higher, 33% (45%) in NH (IH), due to the fact that larger clustering effects are observed in the fully-degenerate phase space distribution. Moreover, due to the clustering effects the differences between the capture rates in NP Case I and II (solid curves vs. dashed curves) become more prominent for larger values of \({\sum} {\kern 1pt} m_\nu\). Therefore, gravitational clustering effects are useful for distinguishing NP scenarios involving different phase space distributions of relic neutrinos.

Capture rate Γ in the PTOLEMY experiment. a Standard Case refers to the scenario predicted by the standard model of cosmology, i.e., only the left(right)-handed chiral states of (anti-)neutrinos were thermally produced in the early Universe. NH (IH) stands for the normal (inverted) mass hierarchy of neutrinos. b NP Case I and II are two new physics scenarios, and in both of them the thermal history of the left(right)-handed chiral states of (anti-)neutrinos is the same as Standard Case. In NP Case I the right(left)-handed chiral states of (anti-)neutrinos were also thermally produced in the early Universe, while in NP Case II the right(left)-handed chiral states of (anti-)neutrinos are non-thermal and possess the fully-degenerate phase space distribution. The number density of the right-handed chiral states of neutrinos is taken to be 28% (52%) of that of the left-handed chiral states of neutrinos in NP Case I (II), when neutrinos began free-streaming

Discussion

In this work, when performing the N-one-body simulation, we did not consider the impact of other nearby galaxies (or clusters) on the clustering of relic neutrinos in the MW. In fact, it was estimated that the Virgo cluster may create a neutrino overdensity of the same order as that generated by the MW8,12. Therefore, we also need to include the gravitational potential of the Virgo cluster into simulation. With both the MW and the Virgo cluster, the shape of the gravitational potential is no longer spherically symmetric. However, since each relic neutrino still follows a one-body motion under the total gravitational potential, the N-one-body simulation and the reweighting technique are still applicable, except that the normalized evolution equations in Eq. (2) and the associated weight for each test particle in Eq. (3) would be in more general forms without the spherical symmetry. Moreover, the currently used matter density profile of the MW still has some uncertainties8, and thus the reweighting technique would also become useful, were we plan to update the N-one-body simulation with more accurate matter density profile in the future. In short, the reweighting technique simplifies the task of using the N-one-body simulation method to evaluate the gravitational clustering effects on relic neutrinos, and is useful for studying the phenomenology associated with the future detection of the cosmic neutrino background.

Methods

DM and baryonic matter density profiles in the MW

The DM density profile is taken to be a generalized NFW form8,

The parameter η is kept to be redshift-independent, while rs(z) and \({\cal N}(z)\) are evolved with redshift z. Here we adopt the best-fit values of \((\eta ,r_{\mathrm{s}}(0),{\cal N}(0))\) = (0.53, 20.29 kpc, 0.73) from a χ2-fit8 to data19. The evolutions of rs(z) and \({\cal N}(z)\) are dictated by the evolutions of the viral quantities Δvir(z) and cvir(Mvir, z), which are defined as

Here Mvir and rvir(z) are the virial mass and radius, respectively, and they are related by the following equation

Note that Mvir is redshift-independent. The evolution of the critical density ρcrit(z) is

where G is the gravitational constant, and H0 and Ωm,0 are the present values of the Hubble parameter and the matter density fraction, respectively. Here we adopt the best-fit values from the Planck data (H0, Ωm,0) = (67.27 km s−1 Mpc−1, 0.3156)10.

Given the three equations Eqs. (8), (9) and (10) and the quantities Mvir, Δvir(z) and cvir(Mvir, z), we can obtain the redshift evolution for \(\left( {r_{\mathrm{s}},r_{{\mathrm{vir}}},{\cal N}} \right)\). The evolution of Δvir(z) is taken to be20

where λ(z) = Ωm(z) − 1 with Ωm(z) being the matter density fraction at redshift z. With Δvir(0) and Eqs. (8), (10) and (11), we obtain Mvir = 3.76 × 1012M⊙, being M⊙ the solar mass. Subsequently, the evolution of rvir(z) is also found from Eqs. (8) and (11). The evolution of rs(z) is related to that of rvir(z) via the concentration parameter cvir(Mvir, z). The evolution of cvir(Mvir, z) is assumed to be cvir(Mvir, z) = \(\beta c_{{\mathrm{vir}}}^{{\mathrm{avg}}}\left( {M_{{\mathrm{vir}}},z} \right)\)8, where \(c_{{\mathrm{vir}}}^{{\mathrm{avg}}}\left( {M_{{\mathrm{vir}}},z} \right)\) is taken from N-body simulations20,

with the functions of A(z) and B(z) given by20

The value of β = 2.09 is then obtained from \(c_{{\mathrm{vir}}}^{{\mathrm{avg}}}\left( {M_{{\mathrm{vir}}},0} \right)\) and cvir(Mvir, 0) = rvir(0)/rs(0). Finally, with the obtained rs(z), the evolution of \({\cal N}(z)\) can be found from Eq. (10).

For the baryonic matter density profile, in reality it has a bulge shape for the central region of radius ~5 kpc19 and extends to be a disc in the outer region. However, since the baryonic matter density is much smaller than the DM density in the disc region, we choose to ignore the disc part, and assume the overall profile of the baryonic matter density to be spherically symmetric. The actual baryonic matter density profile as a function of the radius at the present time is adopted from Fig. 2 in ref. 8. The redshift dependence of baryonic matter profile is modeled with a normalization factor \({\cal N}_{\mathrm{b}}(z)\)8, and the evolution of \({\cal N}_{\mathrm{b}}(z)\) is found by averaging over the evolution of the total stellar mass as obtained in eight MW-sized simulated halos21.

Benchmark N-one-body simulation

In the benchmark N-one-body simulation, we set m ν = 0.15 eV and consider relic neutrinos with a Fermi–Dirac phase space distribution. The normalized evolution equations in Eq. (2) are used, and the scale factor is evolved as

We utilize an iteration procedure to discretize the initial phase space into finer parts5,8, so that a smooth neutrino density profile can be achieved up to ~ 5 kpc. Because of spherical symmetry, the set of variables to be discretized is (r, y, ψ). In general, we have r ∈ [0, ∞), y ∈ [0, ∞) and ψ ∈ [0, π). However, for obtaining the neutrino overdensity around the Earth, we can restrict the ranges for (r, y, ψ). Specifically, we consider two regions of r, an inner region RI: r ∈ [0, 14.3 Mpc), and a outer region RO: r ∈ [14.3 Mpc, rmax]. The value of rmax is taken to be the maximal radial distance that a neutrino with mass m ν can travel, given that it must arrive at the Earth at z = 0 and with a momentum pmax. Here pmax depends on the form of f(y), e.g., for the thermal case we can truncate y to ymax = 10, as the contribution from y > 10 is negligible. Although for m ν = 0.15 eV setting rmax = 150 Mpc is sufficient, we here take rmax = 350 Mpc in order to cover smaller neutrino masses.

In the inner region RI we consider y ∈ [0, 10] and ψ ∈ [0, π). In the coarse scan we set the resolution of r to be Δr = 14 kpc, and divide the whole ranges of y and ψ into 120 parts evenly. After the coarse scan, we select the chunks that end up in the sphere of r < r7 = 7 Mpc, and further divide the ranges of r, y and ψ into another 2, 4 and 4 parts, respectively, for the fine scan.

For the outer region RO, we first notice from the results of ref. 5 that when m ν ≲ 0.3 eV and Mm ≲ 1013M⊙, with Mm being the total mass of the gravitational source, the clustering effect of neutrinos is rather weak beyond the distance r7. As a result, the initial direction of the momentum can be confined to ψ(r) ∈ [π–r7/r), as the test particles with ψ(r) < π–r7/r would never reach the location of the Earth. The range of y in RO is also bounded as y(r) ∈ [ymin(r), ymax(r)]. The existence of ymin is due to the fact that a minimum velocity is always needed in order to reach the location of the Earth, while for ymax it is mainly because an escape velocity exists for a given gravitational potential. In the actual simulation, we obtain the dependence of ymin and ymax on r through a quick numerical scan. Specifically, in the quick scan we vary y within a wide range while having ψ ∈ [π–r7/r), and then find out the allowed range of y that leads to the final value of r below r7. The lower and upper limits of such an allowed range of y yield ymin and ymax, respectively. We repeat this kind of numerical scan for a few values of r, and then perform a parametric fit to obtain the dependence of ymin and ymax on r. Having found the ranges of y and ψ, we then perform a coarse scan with a resolution of Δr = 140 kpc and divisions of 120 parts for both y and ψ. After the coarse scan, we again select the chunks that end up within the sphere of r < r7, and then perform two rounds of fine scan. In the first round of fine scan, we further divide the ranges of y and ψ into another five parts for the selected chunks from the coarse scan. In the second round of fine scan we focus on the chunks that end up within the sphere of r < 140 kpc from the first round of fine scan, and another divisions of 20 parts are applied to both y and ψ.

The last step of N-one-body simulation is to reconstruct the neutrino density profile from the discrete evolved samples. Adopting the kernel method22 and with spherical symmetry, the neutrino number density profile can be estimated as

with the kernel function K(r, r i , d) given by

Here i is the sample index, w i (r i ) denotes the weight (final radial distance) of the sample i, and N is the total number of samples. The window size d plays a similar role as the bin size in the regular histogram. Therefore, too small values of d would lead to large shot noise, while too large values would smooth out the detailed structure of interest. In this work we set d = 8 kpc, and find that varying d by 3 kpc would modify the neutrino density n ν (r⊕) by around 10%. Note that a similar level of uncertainty around 8% due to discrete sampling is also observed in ref. 8, and within the uncertainties our simulated results for the case of m ν = 0.15 eV agree with those in ref. 8.

Capture rate in the PTOLEMY experiment

The capture rate of relic neutrinos in the PTOLEMY experiment can be calculated as13

where s ν denotes the helicity of neutrinos, j labels the neutrino mass eigenstate, and n j (s ν ) is the local number density of neutrinos with mass m j and helicity s ν . In addition, the total number of tritium nuclei is represented by NT, and \(\bar \sigma\) = 3.834 × 10−45 cm2 is the cross-section for the capture of relic neutrino on tritium nuclei. Since only the electron neutrinos can be captured by the tritium nuclei, we need to project each neutrino mass eigenstate into the electron neutrino flavor state, resulting in the factor \(| {U_{{\mathrm{e}}j}} |^2\) in the above formula. The lepton mixing parameters \(| {U_{{\mathrm{e}}j}} |^2\) are found by adopting the best-fit values of neutrino oscillation parameters18, i.e., \(\left( {\left| {U_{{\mathrm{e}}1}} \right|^2,\left| {U_{{\mathrm{e}}2}} \right|^2,\left| {U_{{\mathrm{e}}3}} \right|^2} \right)\) = (0.665, 0.314, 0.022). The spin-dependent factor C(s ν ) is given by C(s ν ) = 1 − \(2s_\nu v_{\nu _j}\) with \(v_{\nu _j}\) being the velocity of neutrino with mass m j . For the total neutrino mass \({\sum} {\kern 1pt} m_\nu\) considered in Fig. 3, all neutrino mass eigenstates are non-relativistic at the present time, so that we can set \(v_{\nu _j}\) ≃ 0 and C(s ν ) ≃ 1. As a result, the last quantity that we need to specify in Eq. (18) is the local number density of neutrinos n j (s ν ), which depends on the underlying physics scenarios and the gravitational clustering effects.

In all the three physics scenarios considered in this work, the nature of Dirac neutrinos is assumed. Therefore, lepton number is conserved and thus only neutrinos, not anti-neutrinos, can be captured. Regarding the neutrino helicity states, in the early Universe both left-handed and right-handed chiral states are relativistic, and therefore they are left-handed and right-handed helical states as well. In the evolution of the Universe, the helicites of neutrinos are preserved, so that at the present time the left-handed and right-handed helical neutrino states correspond to the left-handed and right-handed chiral states in the early Universe, respectively. In Standard Case, the standard model of cosmology predicts the average number density of left-handed helical neutrino states to be n0 = 56 cm−3 for each mass eigenstate at the present time, while almost no existence of right-handed helical states. For a given value of the total neutrino mass \({\sum} {\kern 1pt} m_\nu\), we can obtain the three individual neutrino masses with the two mass-squared differences from neutrino oscillation experiments. Here we adopt \({\mathrm{\Delta }}m_{21}^2 \equiv m_2^2 - m_1^2\) = 7.56 × 10−5 eV2 and \(\left| {{\mathrm{\Delta }}m_{31}^2} \right| \equiv \left| {m_3^2 - m_1^2} \right|\) = 2.55 × 10−3 eV2 from ref. 18. Taking \({\sum} {\kern 1pt} m_\nu\) = 0.23 eV as an example, we obtain (m1, m2, m3) = (0.0711 eV, 0.0717 eV, 0.087 eV) in NH. From the fitted function in Eq. (5) we find that the neutrino density contrasts δ ν are (0.22, 0.23, 0.35) for the three mass eigenstates, respectively, and therefore the corresponding number densities of left-handed helical states around the Earth are 68.44, 68.64 and 75.53 cm−3. Finally, from Eq. (18) we obtain the capture rate Γ = 4.97 yr−1 in this case. The calculation of capture rates in NP Case I and II can be performed similarly, except that in NP Case I and II there are additional contributions from the right-handed helical states of neutrinos, whose average number densities at the present time are taken to be 0.28n0 and 0.52n0 for each mass eigenstate in NP Case I and II, respectively. Gravitational clustering effects on the right-handed helical states are calculated in the same way as the left-handed helical states, except that in NP Case II the fitted relation for the fully-degenerate phase space distribution should be used.

Data availability

The data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Shvartsman, B. F., Braginsky, V. B., Gershtein, S. S., Zeldovich, Y. B. & Khlopov, M. Y. Possibility of detecting relic massive neutrinos. JETP Lett. 36, 277–279 (1982).

Betts, S. et al. Development of a relic neutrino detection experiment at PTOLEMY: Princeton Tritium Observatory for Light, Early-Universe, Massive-Neutrino Yield. Preprint at: http://arXiv.org/abs/1307.4738 (2013).

Lesgourgues, J. & Pastor, S. Massive neutrinos and cosmology. Phys. Rep. 429, 307–379 (2006).

Emberson, J. D. et al. Cosmological neutrino simulations at extreme scale. Res. Astron. Astrophys. 17, 085 (2017).

Ringwald, A. & Wong, Y. Y. Y. Gravitational clustering of relic neutrinos and implications for their detection. JCAP 0412, 005 (2004).

Singh, S. & Ma, C. P. Neutrino clustering in cold dark matter halos: Implications for ultrahigh-energy cosmic rays. Phys. Rev. D 67, 023506 (2003).

Navarro, J. F., Frenk, C. S. & White, S. D. M. The structure of cold dark matter halos. Astrophys. J. 462, 563–575 (1996).

de Salas, P. F., Gariazzo, S., Lesgourgues, J. & Pastor, S. Calculation of the local density of relic neutrinos. JCAP 1709, 034 (2017).

Bertschinger, E. Cosmological dynamics: course 1. Preprint at: http://arXiv.org/abs/astro-ph/9503125 (1995).

Ade, P. A. R. et al. Planck 2015 results: XIII. Cosmological parameters. Astron. Astrophys. 594, A13 (2016).

Li, Y. F. & Xing, Z. Z. Captures of hot and warm sterile anti-neutrino dark matter on EC-decaying Ho-163 nuclei. JCAP 1108, 006 (2011).

Villaescusa-Navarro, F., Miralda-Escudé, J., Peña-Garay, C. & Quilis, V. Neutrino halos in clusters of galaxies and their weak lensing signature. JCAP 1106, 027 (2011).

Long, A. J., Lunardini, C. & Sabancilar, E. Detecting non-relativistic cosmic neutrinos by capture on tritium: phenomenology and physics potential. JCAP 1408, 038 (2014).

Chen, M. C., Ratz, M. & Trautner, A. Nonthermal cosmic neutrino background. Phys. Rev. D 92, 123006 (2015).

Zhang, J. & Zhou, S. Relic right-handed Dirac neutrinos and implications for detection of cosmic neutrino background. Nucl. Phys. B 903, 211–225 (2016).

Horvat, R., Trampetic, J. & You, J. Spacetime deformation effect on the early Universe and the PTOLEMY experiment. Phys. Lett. B 772, 130–135 (2017).

Huang, G. Y. & Zhou, S. Discriminating between thermal and non-thermal cosmic relic neutrinos through an annual modulation at PTOLEMY. Phys. Rev. D 94, 116009 (2016).

de Salas, P. F., Forero, D. V., Ternes, C. A., Tortola, M. & Valle, J. W. F. Status of neutrino oscillations 2017. Preprint at: http://arXiv.org/abs/1708.01186 (2017).

Pato, M. & Iocco, F. The dark matter profile of the Milky Way: a non-parametric reconstruction. Astrophys. J. 803, L3 (2015).

Dutton, A. A. & Macciò, A. V. Cold dark matter haloes in the Planck era: evolution of structural parameters for Einasto and NFW profiles. Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 441, 3359–3374 (2014).

Marinacci, F., Pakmor, R. & Springel, V. The formation of disc galaxies in high resolution moving-mesh cosmological simulations. Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 437, 1750–1775 (2014).

Merritt, D. & Tremblay, B. Nonparametric estimation of density profiles. Astron. J. 108, 514–537 (1994).

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Zhi-zhong Xing for suggesting the topic and useful discussions. We also thank Ran Ding, Guo-yuan Huang, Yandong Liu and Shun Zhou for useful discussions. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants No. 11522540 and No. 11690021), the National Program for Support of Top-notch Young Professionals, the Provincial Department of Education of Liaoning (Grant No. L2012087), and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant No. 2017M610008).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Z. and X.Z. jointly initiated the project. Both authors have contributed to this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, J., Zhang, X. Gravitational clustering of cosmic relic neutrinos in the Milky Way. Nat Commun 9, 1833 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-04264-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-04264-y

This article is cited by

-

Unstable cosmic neutrino capture

Journal of High Energy Physics (2022)

-

Exploring neutrino mass and mass hierarchy in interacting dark energy models

Science China Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy (2020)

-

Dark energy versus modified gravity: Impacts on measuring neutrino mass

Science China Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.