Abstract

Carbon coating is a commonly employed technique for improving the conductivity of active materials in lithium ion batteries. The carbon coating process involves pyrolysis of organic substance on lithium iron phosphate particles at elevated temperature to create a highly reducing atmosphere. This may trigger the formation of secondary phases in the active materials. Here, we observe a conductive phase during the carbon coating process of lithium iron phosphate and the phase content is size, temperature, and annealing atmosphere dependent. The formation of this phase is related to the reducing capability of the carbon coating process. This finding can guide us to control the phase composition of carbon-coated lithium iron phosphate and to tune its quality during the manufacturing process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the first report in 1997, olivine LiFePO4 (LFP) as an environmentally benign and a safer cathode material has been widely studied in the field of energy storage1. Considerable efforts have been devoted toward improving the intrinsic low electronic and ionic conductivity of this material2,3,4. Surface carbon coating is often used to increase the electrical conductivity of LFP and has proven to be an effective strategy4,5. This has led to significant progress for the wide-spread application of LFP in commercial lithium ion batteries during the last two decades6,7,8. However, an in-depth understanding of surface chemistry changes during the carbon coating process remains elusive. Carbon coating usually involves a strong reducing environment and often requires high temperature. This increases the reaction kinetics between the surface of LFP and the supplied carbon9. As a result, secondary phases will form on the surface, thereby altering the electronic/ionic conductivity of LFP10,11,12,13,14. Previously, a Fe2P2O7 secondary phase was observed on the surface of hydrothermally synthesized LFP. The origin of such impurity phase formation is ascribed to more FeLi antisite formed at lower temperature synthesis than high temperature solid-state reactions15,16,17. The formation of another secondary phase, iron phosphide, has been shown to be closely related to the annealing procedure employed and undoubtly influence the physical properies of LFP. Annealing the LFP at different temperatures/atmosphere, iron phosphides (FeP, Fe2P, and Fe3P) were detected with XRD18,19. By controlling the content of the iron phosphides, the long-term cycle performance and rate performance of carbon-coated LFP was improved20,21,22. In addition, work on the carbon quality of LFP suggested that more graphitic carbon layers were easily formed with iron phosphide inside LFP9. Because the carbon coating process on LFP is a multi-component system at small scale, it is very difficult to define the presence of secondary phase, to map the distribution of secondary phase, to record the change of secondary phase, and the control of secondary phase. Therefore, understanding the formation mechanism for emergence of secondary phases would be highly beneficial, especially for LFP manufacturers.

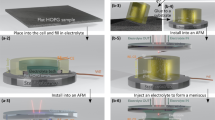

In our previous study, we found interface reactions occurred between the carbon layer and LFP during the carbon coating process. The evaporation of lithium at high temperature results in the formation of an inert impurity phase Fe2P2O7. With the help of advanced techniques, we clearly recorded the location and distribution of surface phases and hypothesized the formation of Fe2P2O723. Our next study shows that the amount of the Fe2P2O7 phase can be controlled, and even be fully removed by tuning parameters applied during the carbon coating process. However, removal of a negative secondary phase in LFP is not the only objective to produce high quality LFP. It would also be essential to improve the electrochemical performance of LFP by tuning electronic conductivity. There have been numerous attempts to increase the electronic conductivity of LFP, such as forming a percolating carbon network on the surface of LFP12,13,14. Furthermore, coating formed on the LFP surface to enhance the lithium ion conductivity, by forming off-stoichiometry composition, is of great interest. Surface engineering on the LFP with the aim of improving the electrochemical performance has been a very promising direction in this field14,24,25,26. Our research goal is to engineer the chemical composition of LFP surface via carbon coating. This method may be effective in creating an appropriate off-stoichiometry LFP with uniform carbon coating on the surface. Such a unique carbon-coated LFP materials could simultaneously resolve both low lithium ion conductivity and electronic conductivity. Due to the highly complex nature of interface reaction, there is no direct way to visualize and monitor the surface chemistry change during carbon coating process. Recently, melt-casting has been shown to be a promising technique in preparing LFP27,28. After polishing the surface of melt-casted LFP ingot, a large flat surface can be obtained. A mirror surface takes the advantage of visualization of detailed surface chemistry changes during carbon coating process, which would greatly help us to understand the reaction at the interface9.

Here in this work, LFP ingot and LFP particles, with different sizes, have been used to demonstrate and present a size-dependent conductive secondary phase formation during carbon coating. Furthermore, surface phase changes are correlated to temperature and reducing atmosphere. Therefore, formation of secondary phase is controlled by LFP particle size, annealing temperature, and reducing atmosphere, simultaneously. LFP particles with appropriate amount of conductive phase are obtained by carefully tuning coating parameters during the carbon coating process. The improved electrochemical performance of LFP materials with conductive phase suggests that such secondary phase has a positive influence. From a thermodynamic point of view, we propose a unified mechanism that can be used to describe the formation of Fe2P phase under different circumstances. In particular, we use LFP ingot sample to demonstrate the direct visualization of this phase change mechanism during carbon coating. Our study on carbon-coated LFP may also enlighten the interests on the interface chemistry research, especially, reactions of insulating materials in reducing atmosphere.

Results

Surface phase formation

As shown in Fig. 1, an intriguing phenomenon of spherical-like phase growth can be seen on the surface of the carbon-coated LFP ingot at 900 °C, and is distinctively different in morphology from the underlying matrix . A close-up view shows that the spherical-like phase is not uniform, with different sizes and shapes observed at various locations. Using energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) mapping, this surface phase was assigned as an Fe-rich phase covered by a layer of carbon. In addition, a region enriched in phosphorus and oxygen suggests the presence of lithium phosphates. We propose that these surface changes are correlated to the carbon coating process as these observations are not found under H2 reduction or pure Ar atmospheres, where no carbon is presented (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Surface conductive phase formation during carbon coating process. a Upper panel: SEM images (left side), BSE images (middle and right); lower panel: EDS mapping of surface conductive phase formation on LiFePO4. b Schematic representation of new phase formation on LiFePO4. Scale bar, 1 mm (SEM image), 200 µm (BSE), and 50 µm (right side BSE and lower panel EDS images)

Characterization of the size-dependent surface phase

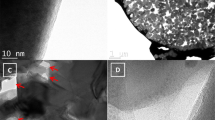

To verify our findings, we further extended our study to powder samples with varying sizes. LFP particles ranging from micro-sized (19 µm) to nano-sized (60 nm) were obtained by ball milling LFP ingot sample (size distribution can be found in Supplementary Fig. 2). Figure 2a reveals XRD patterns of carbon-coated LFP with different sizes. Small peaks in the range of 38–48° (gray area) are clearly observed for all LFP particles, and can be assigned to Fe2P (JCPDS No 85-1725). As LFP particle size decreases, peak intensities for Fe2P intensify (See the inset in Fig. 2a). To support the evidence for a size-dependent relationship on the formation of Fe2P, two types of LFP samples with size of 560 nm and 60 nm were characterized using transmission electron microscope (TEM) following carbon coating at 900 °C. It is seen that the size distributions of 560 nm and 60 nm LFP particles has grown due to high temperature (Supplementary Fig. 3). Interestingly, Fig. 2b displays small spherical particles adjacent to larger LFP particles. Selected Area Electron Diffraction (SAED) pattern of that particulate are consistent with Fe2P [001]. Moreover, the amount of Fe2P phase formed on the 60 nm LFP is bigger than that found for 560 nm LFP. This provides good evidence for a correlation existing between Fe2P phase formation and LFP particle size. From the inset of the HRTEM images in Supplementary Fig. 4, the carbon coating on Fe2P is about 6 nm and is thicker than the carbon coating on LFP, which is around 3 nm. The smaller size Fe2P with thicker carbon coating would be beneficial in improving LFP conductivity.

Size-dependent properties of Fe2P phase formation. a XRD pattern of different size LFP particles after carbon coating at 900 °C. b HRTEM Fe2P phase for 60 nm LFP and 560 nm LFP annealed at 900 °C. Inset shows the SAED pattern of Fe2P phase and HRTEM images of Fe2P phase. Scale bar, 500 nm in TEM, 5 nm in HRTEM

To get a clear evidence of phase change process, carbon coating was directly observed on powder LFP (nano size LFP) by in-situ SEM observations combined with injection of carbon precursor23. Following carbon precursor injection, the particles begin to aggregate and then shrink, ending with a melted product. Using a higher magnification SEM (Supplementary Fig. 5), the formation of secondary phase on the surface of primary LFP particles can be seen.

Temperature and atmospheric dependent phenomenon

The Fe2P new phase could be easily formed at high temperature carbon coating on LFP particles. Figure 3a displays the formation of a new phase following carbon coating of 60 nm LFP at different temperatures. The XRD pattern reveals the formation of Fe2P begins at 850 °C and increases in peaks intensity at 900 °C, suggesting that phase formation of Fe2P is temperature dependent. If we extend the LFP particle size to 560 nm and 19 µm, 560 nm LFP shows size-dependent phenomenon as 60 nm LFP (Supplementary Fig. 4), but the Fe2P phase formation is delayed to 900 °C (Supplementary Fig. 5). This suggests that the formation of Fe2P phase is related to both size and temperature.

Temperature dependent and atmosphere dependent properties of Fe2P phase formation. a XRD pattern of 60 nm LFP after carbon coating in Ar from 700–900 °C. b XRD pattern of 60 nm LFP after carbon coating in Ar/H2 from 600–800 °C. c TEM characterization of Fe2P phase and LFP for 60 nm LFP annealed in Ar/H2 (left side) and Ar (right side) gas at 700 °C. Inset of left picture is the diffraction pattern of Fe2P phase and HRTEM images, inset of right picture is the diffraction pattern of LFP phase and HRTEM images. Scale bar, 500 nm in TEM, 5 nm in HRTEM in the left picture. Scale bar, 200 nm in TEM, 5 nm in HRTEM in the right picture

Apart from temperature, annealing atmosphere is another critical factor during carbon coating of LFP. To investigate the influence of annealing atmosphere, we intentionally introduced H2 gas during the carbon coating process and observed the corresponding surface phase changes. Figure 3b displays the atmospheric dependent nature of Fe2P impurity phase formation. Carbon coating is performed on 60 nm LFP in the temperature range of 600–800 °C for Ar/H2. XRD patterns demonstrate that using an Ar/H2 reducing atmosphere, a critical temperature of 700 °C is required for the formation of Fe2P phase rather than the 850 °C that is required in a pure Ar atmosphere. For 560 nm LFP, Fe2P phase formation temperature reduced to 700 °C, as well as in Ar/H2 (Supplementary Fig. 6). Even for 19 µm LFP particles, Fe2P phase formation temperature was found to occur at 800 °C, a lower temperature than in pure Ar (900 °C) (Supplementary Fig. 7).

To further identify the Fe2P phase distribution in LFP particles, surface morphology was examined following carbon coating at 700 °C. SEM images, shown in Supplementary Fig. 8, demonstrate the formation of large crystals on 60 nm LFP following carbon coating in a more reducing environment (Ar/H2). In contrast, no such particles are observed for 60 nm LFP coated in Ar gas. To obtain detailed information about the particles, we picked 60 nm LFP in Ar and Ar/H2 for TEM characterization. A large rod-like crystal can be seen for 60 nm-coated LFP in a reducing atmosphere. Based on the SAED diffraction pattern, this feature can be assigned to hexagonal Fe2P phase (As shown in Fig. 3c). Nevertheless, no such crystal formation was observed for 60 nm LFP coated in Ar gas, and is further supported by clear polycrystalline LFP diffraction rings. From the HRTEM images in Fig. 3c, the rod-like Fe2P phase is shown to be covered by a 2 nm-thick carbon coating, while the nano-LFP is covered with thicker carbon coating (5 nm). Thus, larger Fe2P phase with thin carbon coating is observed for 60 nm LFP after carbon coating in Ar/H2.

Electrochemical performance of LFP with new phase

In order to verify the electronic conductivity improvement brought on by Fe2P, electrochemical performance of LFP was evaluated. As discussed above, Fe2P phase formation in a reducing environment results in the formation of large crystals covered by a thin coating of carbon. This feature may hinder lithium ion transport. Furthermore, SEM and TEM images of 60 nm LFP coated at 900 °C in Ar exhibits large Fe2P and LFP particles agglomerated together due to the elevated temperature employed (Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5). Finally, we chose 560 nm LFP to illustrate the effect Fe2P on the electrochemical performance of LFP. Figure 4a displays the electrochemical performance of 560 nm LFP particles, following carbon coating under various conditions. Clearly, 560 nm LFP annealed at 900 °C has decreased capacity and cycle performance, compared to pure LFP samples, demonstrating only 67 mAh g–1 of capacity after 100 cycles. Two possible reasons may be given for the decreased capacity observed. The first is related to the agglomeration of LFP particles at high temperature, as seen in Supplementary Fig. 4. The second reason is the high content of Fe2P phase resulting in decreased lithium conductivity. To verify the influence of Fe2P phase content on performance, two 560 nm LFP samples were prepared by annealing them at 850 °C for 20 min and 1 h, respectively. The LFP sample annealed at 850 °C presents less Fe2P phase in LFP than 900 °C, as indicated by the XRD pattern in Supplementary Fig. 6, while the sample coated at 800 °C is pure LFP phase. However, the electrochemical performance of the sample annealed at 850 °C and 800 °C demonstrates that the one annealed at a higher temperature results in improved performance. Although the 800 °C-coated LFP sample exhibits a high capacity in the first 60 cycles, the capacity quickly fades. Conversely, after 100 cycles, the 850 °C-coated LFP sample manages to deliver 109 mAh g–1, while the 800 °C-coated LFP only shows 104 mAh g–1, and capacity retention is improved from 88.9% in 800 °C-coated LFP to 94.0 % in 850 °C-coated LFP. If we reduce the amount of Fe2P phase by reducing coating time to 20 min, it results in a large improvement to the electrochemical performance with the sample delivering 125 mAh g–1 after 100 cycles with capacity retention of 100 %.

To clarify the influence of H2 gas, 60 nm LFP annealed in different atmospheric conditions were tested and shown in Fig. 4b. It can be seen that the 60 nm LFP annealed in Ar shows a stable cycle performance for 100 cycles without capacity decaying. On the contrary, the 60 nm LFP annealed in Ar/H2 shows a lower capacity of 140 mAh g–1 in the first cycle and drops to 127 mAh g–1 after 100 cycles, with a retention rate of 90.7%. In order to find the reason, electrochemical impedance spectra of 60 nm LFP and 560 nm LFP annealed in Ar and Ar/H2 were recorded before cycling (Supplementary Fig. 9 and Supplementary Table 1). It is shown that 60 nm LFP with addition of H2 gas, a increase of resistance is observed. The high resistance comes from the big size Fe2P rod formed in LFP sampled annealed in Ar/H2, whichblocks the transport of electrons/lithium ions (Fig. 3c). To sum up, these results indicate that carefully controlling Fe2P content can increase the capacity of half-cell LFP electrode by improving electronic conductivity and allowing for the formation of a conductive percolating network throughout the electrode (Fig. 4c)20,29,30. This improvement can also be attributed to the formation of a lithium pyrophosphate phase (Li4P2O7) during the carbon coating process, as shown in the Supplementary Fig. 10. Lithium phosphate is known to be a good lithium ion conductor and will aid in improving electrochemical performance31.

Discussion

The formation of conductive Fe2P phase has been previously reported by Nazar et al12. However, only EDS information was presented that demonstrated an increased ratio of Fe/P at the grain boundary of LFP slices. In a later study published by Chung et al32, 3D phase morphology of Fe2P was determined by a combination of electron tomography using high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy, EDS, and electron energy-loss spectroscopy. However, detailed study regarding phase formation mechanism and control of the secondary phase during carbon coating does not exist. In our work, we demonstrate the importance of carbon coating effect on the formation of Fe2P. Supplementary Figs. 11 and 12 show the surface phase evolution with carbon coating time, with chemical composition changing on LFP ingot, some spherical-like Fe-rich phase is formed on the surface.

Formation of Fe2P phase is dependent on size, annealing temperature, and atmosphere, which is ascribed to the interface reaction between surface carbon and underlying LFP phase. Previously, our group proposed a carbon-competitive diffusion/deposition theory to explain the size-dependent phenomenon of impurity growth in LFP23. The formation of carbon layer on LFP involved a competition of carbon deposition on surface and carbon diffusion into bulk LFP. Smaller particles underwent a high rate of carbon deposition, resulting in rapid encapsulation of the LFP particle with carbon. This resulted in limited carbon diffusion to bulk LFP, leading to a thinner surface reduced layer. On the contrary, bigger particles consumed carbon slowly and had a slow carbon deposition rate, resulting in the carbon atoms being submerged into the crystalline lattice of LFP. Then, the surface of LFP was reduced to a secondary phase. Although this theory allowed us to postulate interface reactions occurring between carbon and LFP, it provides little insight toward the effect of temperature and reducing gas with carbon decomposition. Therefore, we provide a new direction in understanding Fe2P phase formation mechanism during carbon coating from a thermodynamic point of view with supporting evidence. (Fig. 5)

Based on the result shown above, Fe2P phase formation on LFP during carbon coating maybe expressed as follows:

The carbon coating process at high temperature involves decomposition of hydrocarbon sources into elemental carbon and reducing gas, accompanied by the formation of Fe2P and lithium phosphate at the LFP surface. At moderate temperatures (800 °C in LFP ingot in Supplementary Fig. 13 and 14), the amount of reducing gas produced is limited, no Fe2P is formed. As temperature increases to 875 °C, an increased amount of reducing gas is created and Fe2P formation occurs on the surface of LFP, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 13–15. Such a phenomenon is in agreement with first principle calculations performed by Ceder et al33. Their results suggest that Fe2P phase formation begins when the oxygen chemical potential \(\mu _{o_2}\)= –16.7 eV. \(\mu _{o_2}\) is determined by temperature and oxygen partial pressure, simultaneously. Higher temperatures, lower oxygen partial pressures and/or the presence of reducing agents corresponds to lower values of \(\mu _{o_2}\). It can explain the temperature dependent phenomenon of Fe2P phase during carbon coating. However, we find that the formation of Fe2P phase during carbon coating is dependent not only on temperature, but also on LFP particle sizes.

LFP particles with different sizes exhibiting different catalytic properties on the decomposition of hydrocarbon were reported in our previous paper. The study demonstrated that smaller LFP particles with large surface area facilitated carbon reduction reaction, resulting in an increased reactivity. The Brunauer–Emmett–Teller surface area of LFP particle was measured through N2 adsorption/desorption isotherms tests (Supplementary Fig. 16 and Supplementary Table 2), the results suggested that Fe2P formation was closely related to the surface area of LFP particles. In addition, carbon content of LFP particle was measured through TGA tests, and smaller LFP with higher carbon content was observed (Supplementary Fig. 17 and Supplementary Table 3). Thus, with increased surface area for 60 nm and 560 nm LFP, the amount of reducing gas produced are increased for smaller LFP particles, leading to a lower \(\mu _{o_2}\) value compared to larger LFP particles undergoing the same process. As a result, the formation of Fe2P phase at 850 °C for 60 nm LFP and 560 nm LFP is easily attainable. However, for 19 µm LFP particle, a temperature of 900 °C is required for the formation of Fe2P phase, suggesting a size-related phenomenon. Based on Ceder's paper, such a Fe2P phase change phenomenon was easily observed in Li-rich LFP33. Our inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES) testing (Supplementary Table 4) on LFP particles also confirms that lithium content is higher in smaller LFP samples.

Furthermore, a reducing gas of Ar/H2 is intentionally introduced during the coating process to create a low oxygen partial pressure \(\mu _{o_2}\). As expected, Fe2P phase formation occurs readily at a lower temperature of 700 °C for 60 nm LFP and 560 nm LFP, and 800 °C for 19 µm LFP in Ar/H2. To further support our observation, we applied the reducing atmosphere for LFP ingot in the carbon coating process. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 18, the spherical-like iron rich Fe2P phase is formed on LFP surface at 800 °C, indicating that Fe2P phase formation has been shifted to lower temperature by altering the annealing environment to a more reducing condition. Moreover, the Fe2P phase formation is independent of carbon precursor choice as Fe2P phase formation occurs in nano-LFP with gas carbon (C2H4) as precursor (Supplementary Fig. 19).

To conclude, we have shown that the formation of surface secondary phase in LFP during carbon coating is dependent on particle size, annealing temperature, and reducing atmosphere. The Fe2P phase transformation process is governed by thermodynamic rules and reaction kinetics. In a mild reducing atmosphere of argon gas, Fe2P phase is formed at high temperatures for all sizes of LFP, but the critical temperature for phase formation in small LFP is lower. Formation of Fe2P phase is closely related to reducing environment during the carbon coating process and is easily formed when the oxygen partial potential \(\mu _{o_2}\) is decreased. Our preliminary data from half-cell show a positive effect on electrochemical performance of LFP with presence of Fe2P through fine-tuning the phase composition. However, the real impact of cycle life must be evaluated using long-term cycling in a range of temperatures with a full cell format. Nevertheless, method developed in this work may be extended to other olivine phosphate or insulated electrode that undergo carbon coating.

Methods

Carbon coating on LFP

The LFP ingot sample was provided by Phostech Lithium Inc. (Now, Johnson Matthey, Montreal, Canada), and the carbon coating process followed our previous report23.

Here, LFP ingot was used as a starting material and reduced to the appropriate size. An ingot sample was used for two main reasons: first one is its commercial availability providing us with a good baseline for understanding ordinary LFP materials. Second, an ingot offers a flat, smooth, and polished surface that is ideal for observing and investigating surface chemistry changes during carbon coating—for both the bulk olivine phase and secondary phases. The experimental details regarding melt-casting of LFP ingot can be found in our previous work27,28. In order to obtain a flat surface on the ingot, we polished the sample using sandpaper (London, 3 M Canada) ranging from coarse (Grit 120) to fine grade (Grit 1500). Following polishing, the samples were cleaned in an ultra-sonicator using ethanol several times.

LFP ingots were ball-milled into particle with different sizes using ZrO2 balls. Size distribution was controlled by ball milling for different times and using different sized ZrO2 balls. The ball milling process used isopropyl alcohol as the media, after the ball-mill process, the obtained precursors were dried in vacuum oven before carbon coating. The particle sizes of LFP were estimated with Image J software by calculating at least 5–10 SEM images.

The carbon-coating experiments on ingot samples were performed in a spray-pyrolysis system, which was previously developed for the synthesis of various nanomaterials. In the experiment, alcohol (anhydrous, chemical grade) was directly used as a carbon precursor and Ar as a carrier and protecting gas. Briefly, the ingot sample with the flat surface facing upward was placed in a quartz tube in Al2O3 crucibles with a tight seal using vacuums gears. Ar (80 sccm) (or with H2, 10 sccm), was introduced into the quartz tube for 20 min to eliminate any oxygen and to create an inert environment. Next, the furnace was heated at a heating rate of 5 °C min–1, and the carbon-coating process was performed at temperatures ranging from 800 °C to 900 °C for 20 min. After the carbon coating process at high temperature, the coated sample was cooled to room temperature naturally within the furnace still under the protection of the Ar atmosphere. Samples were collected for further experiments once they were cooled down.

Carbon coating of LFP powders were similar to ingot samples, except that we used the lactose as the carbon sources instead of alcohol. The LFP powders were fully mixed with lactose using water or isopropyl alcohol (carbon source content was 10 wt. %, the concentration was 2 g L–1 based on weight of LFP), then the suspension was mixed ultrasonically, and was then allowed to evaporate to dryness. The sample was annealed in Ar (with H2) atmosphere at a ramp rate of 5 °C min–1, from 600 °C to 900 °C.

Physical characterization

Crystal structure and phase composition of carbon-coated LFP were collected using the X-ray diffraction (D8 Advance, Bruker) in the range of 10–90° with a step of 0.01° per seconds. Slow scans in the range of 28–33° were also performed to provide detail on the formation of impurity phases. The carbon-coated LFP powders were subjected to Hitachi 4800 SEM equipped with EDS detector. The working voltage employed for EDS mapping was 20 kV. The Raman spectra were conducted at HORIBA Scientific LabRAM with a laser (λ = 532.3 nm) as the excitation source. Raman spectroscopy maps from at the sample were collected in autofocus mode with a spatial resolution of ca. 2 µm. The detailed structure of carbon-coated LFP particles are investigated by HR-TEM (JEOL 2010 FEG) operating at an accelerating voltage of 20 kV, diffraction patterns were recorded using the SAED mode. Thermo-gravimetric analysis (TGA) was carried out on a TA SDT Q600 in an air atmosphere from room temperature to 900 °C at a rate of 10 C min–1. N2 adsorption/desorption isotherms of LFP particles were performed using a Folio Micromeritics TriStar II Surface Area and Pore Size Analyzer.

Electrochemical tests

The electrochemical performance of carbon-coated LFP were tested in 2032 coin cells, using a Li metal foil as a counter electrode. The electrode is composed of 80 wt.% carbon-coated LFP as active material, 10 wt.% PvDF as binder, and 10 wt.% carbon black as conductive agent, with an active material loading of 1.5–2 mg cm–2. 1 M LiPF6 in EC, DEC, and EMC with a volume ratio of 1:1:1 was employed as an electrolyte along with Celgard 2400 as a separator. The cells were assembled in an Ar-filled glove box with oxygen and water levels below 1 ppm. Charge–discharge cycling using a constant current mode was performed on an Arbin BT-2000 Battery Test System. All the electrochemical measurements were carried out in a voltage range of 2.2–4.2 V at RT.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Padhi, A. K., Nanjundaswamy, K. S. & Goodenough, J. B. Phospho olivines as positive electrode materials for rechargeable lithium batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 144, 1188–1194 (1997).

Wang, J. & Sun, X. Olivine LiFePO4: the remaining challenges for future energy storage. Energy Environ. Sci. 8, 1110–1138 (2015).

Wang, Y., He, P. & Zhou, H. Olivine LiFePO4: development and future. Energy Environ. Sci. 4, 805–817 (2011).

Wang, J. & Sun, X. Understanding and recent development of carbon coating on LiFePO4 cathode materials for lithium-ion batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 5, 5163–5185 (2012).

Herstedt, M. et al. Surface chemistry of carbon-treated LiFePO4 particles for Li-ion battery cathodes studied by PES. Electrochem. Solid State Lett. 6, A202–A206 (2003).

Wilcox, J. D., Doeff, M. M., Marcinek, M. & Kostecki, R. Factors influencing the quality of carbon coatings on LiFePO4. J. Electrochem. Soc. 154, A389–A395 (2007).

Chen, L., Yuan, Y. Q., Feng, X. & Li, M. W. Enhanced electrochemical properties of LiFe1−xMnxPO4/C composites synthesized from FePO4·2H2O nanocrystallites. J. Power Sources 214, 344–350 (2012).

Oh, S. W. et al. Double carbon coating of LiFePO4 as high rate electrode for rechargeable lithium batteries. Adv. Mater. 22, 4842–4845 (2010).

Wang, J. et al. Interaction of carbon coating on LiFePO4: A local visualization study of the influence of impurity phases. Adv. Funct. Mater. 23, 806–814 (2013).

Yu, D. Y. W. et al. Impurities in LiFePO4 and their influence on material characteristics. J. Electrochem. Soc. 155, A526–A530 (2008).

Trudeau, M. L. et al. In situ high-resolution transmission electron microscopy synthesis observation of nanostructured carbon coated LiFePO4. J. Power Sources 196, 7383–7394 (2011).

Herle, P. S., Ellis, B., Coombs, N. & Nazar, L. F. Nano-network electronic conduction in iron and nickel olivine phosphates. Nat. Mater. 3, 147–152 (2004).

Kang, B. & Ceder, G. Battery materials for ultrafast charging and discharging. Nature 458, 190–193 (2009).

Wagemaker, M., Ellis, B. L., Lutzenkirchen-Hecht, D., Mulder, F. M. & Nazar, L. F. Proof of supervalent doping in olivine LiFePO4. Chem. Mater. 20, 6313–6315 (2008).

Chung, S. Y., Choi, S. Y., Kim, T. H. & Lee, S. Surface-orientation-dependent distribution of subsurface cation-exchange defects in olivine-phosphate nanocrystals. ACS Nano 9, 850–859 (2015).

Paolella, A. et al. Cation exchange mediated elimination of the Fe-antisites in the hydrothermal synthesis of LiFePO4. Nano Energy 16, 256–267 (2015).

Paolella, A. et al. Accelerated removal of Fe-antisite defects while nanosizing hydrothermal LiFePO4 with Ca2+. Nano. Lett. 16, 2692–2697 (2016).

Xu, Y., Lu, Y., Yan, L., Yang, Z. & Yang, R. Synthesis and effect of forming Fe2P phase on the physics and electrochemical properties of LiFePO4/C materials. J. Power Sources 160, 570–576 (2006).

Lin, Y., Gao, M. X., Zhu, D., Liu, Y. F. & Pan, H. G. Effects of carbon coating and iron phosphides on the electrochemical properties of LiFePO4/C. J. Power Sources 184, 444–448 (2008).

Song, M. S. et al. Amphoteric effects of Fe2P on electrochemical performance of lithium iron phosphate–carbon composite synthesized by ball-milling and microwave heating. J. Power Sources 180, 546–552 (2008).

Yin, Y. et al. High-rate capability of LiFePO4 cathode materials containing Fe2P and trace carbon. J. Power Sources 199, 256–262 (2012).

Zhang, L. et al. Synthesis of Fe2P coated LiFePO4 nanorods with enhanced Li-storage performance. J. Alloy. Compd. 627, 132–135 (2015).

Wang, J. et al. Size-dependent surface phase change of lithium iron phosphate during carbon coating. Nat. Commun. 5, 3415–3423 (2014).

Zaghib, K., Mauger, A., Gendron, F. & Julien, C. Surface effects on the physical and electrochemical properties of thin LiFePO4 particles. Chem. Mater. 20, 462–469 (2007).

Julien, C. M., Mauger, A. & Zaghib, K. Surface effects on electrochemical properties of nano-sized LiFePO4. J. Chem. Mater. 21, 9955–9968 (2011).

Kayyar, A., Qian, H. & Luo, J. Surface adsorption and disordering in LiFePO4 based battery cathodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 221905–221908 (2009).

Gauthier, M. et al. Melt casting LiFePO4 I. Synthesis and characterization. J. Electrochem. Soc. 157, A453–A462 (2010).

MacNeil, D. et al. Melt Casting LiFePO4 II. particle size reduction and electrochemical evaluation. J. Electrochem. Soc. 157, A463–A468 (2010).

Liu, Y., Cao, C., Li, J. & Xu, X. A novel synthesis of Fe2P–LiFePO4 composites for Li-ion batteries. J. Appl. Electrochem 40, 419–425 (2010).

Kang, H. C. et al. Optimized solid-state synthesis of LiFePO4 cathode materials using ball-milling. J. Power Sources 179, 340–346 (2008).

Rho, Y. H., Nazar, L. F., Perry, L. & Ryan, D. Surface chemistry of LiFePO4 studied by Mössbauer and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy and its effect on electrochemical properties. J. Electrochem. Soc. 154, A283–A289 (2007).

Chung, S. Y., Kim, Y. M. & Choi, S. Y. Direct physical imaging and chemical probing of LiFePO4 for Lithium-Ion batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 20, 4219–4232 (2010).

Ong, S. P., Wang, L., Kang, B. & Ceder, G. Li-Fe-P-O2 phase diagram from first principles calculations. Chem. Mater. 20, 1798–1807 (2008).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), Automotive Partnership of Canada Program, Johnson Matthey (Previous Phostech Lithium Inc.), Canada Research Chair (CRC) Program, Canadian Light Source (CLS), McMaster Microscopy Centre for HRTEM, and Western University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.S. conceived the overall project; Y.L. designed/performed the experiments, data analysis, and wrote the manuscript; J.L., J.W., and B.X. helped with carbon-coating experiment; M.N.B. and A.L performed XRD characterization; R.L. helped with TEM characterization and discussion; M.N.B, W.X., and T.K.S. performed synchrotron characterization and discussion; G.L. and X.S. interpreted the results.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Liu, J., Wang, J. et al. Formation of size-dependent and conductive phase on lithium iron phosphate during carbon coating. Nat Commun 9, 929 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-03324-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-03324-7

This article is cited by

-

Boosting fast energy storage by synergistic engineering of carbon and deficiency

Nature Communications (2020)

-

Carbon solid lubricants: role of different dimensions

The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology (2020)

-

Nano-scale hollow structure carbon-coated LiFePO4 as cathode material for lithium ion battery

Ionics (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.