Abstract

Copper electrodes have been shown to be selective toward the electroreduction of carbon dioxide to ethylene, carbon monoxide, or formate. However, the underlying causes of their activities, which have been attributed to a rise in local pH near the surface of the electrode, presence of atomic-scale defects, and/or residual oxygen atoms in the catalysts, etc., have not been generally agreed on. Here, we perform a study of carbon dioxide reduction on four copper catalysts from −0.45 to −1.30 V vs. reversible hydrogen electrode. The selectivities exhibited by 20 previously reported copper catalysts are also analyzed. We demonstrate that the selectivity of carbon dioxide reduction is greatly affected by the applied potentials and currents, regardless of the starting condition of copper catalysts. This study shows that optimization of the current densities at the appropriate potential windows is critical for designing highly selective copper catalysts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The reduction of carbon dioxide (CO2) to fuels and chemical feedstocks using renewable electricity has the potential of becoming a key component in the development of a sustainable carbon cycle1,2. This process requires selective, efficient, and stable electrocatalysts before it can be implemented in the industrial scale. Among the metal electrocatalysts studied, copper is the only metal that can reduce CO2 to significant amounts of hydrocarbons and oxygenates3,4. Of these products, methods to selectively form formate (HCOO−)5, carbon monoxide (CO)6, methane (CH4)7, ethylene (C2H4)8,9,10 and ethanol (C2H5OH)11 have been extensively pursued.

To understand how these products are formed on copper, Peterson and Nørskov modeled the reduction of CO2 on Cu(211) surface (a stepped surface) using density functional theory (DFT)12. As the applied potential became more negative, CO2 was first reduced to HCOO− and CO, from −0.41 V vs. RHE (reversible hydrogen electrode) onward. C2H4 and CH4 were the next major products and evolved at potentials negative to −0.71 V vs. RHE. These theoretical predictions are consistent with the findings reported earlier by Hori et al. on a polycrystalline Cu surface, where HCOO− and CO were produced first, followed by C2H4 and CH413. Interestingly, when Cu single-crystal surfaces were studied using chronopotentiometry at −5 mA cm−2 in 0.1 M KHCO3 electrolyte, the selectivity between C2H4 and CH4 changed. Cu(100) and Cu(111) were, respectively, found selective for C2H4 and CH4 formation. Further optimization of C2H4 production could be achieved by using stepped-Cu(100) surfaces14. For example, the faradaic efficiency (FE) of C2H4 reached 50%, while CH4 was suppressed to 5% on a Cu(S)-[4(100)×(111)] electrode polarized at −5 mA cm−2 (−0.94 V vs. RHE). Oddly and still without an explanation, the selectivity of neither C2H4 nor CH4 seemed to improve significantly on stepped-Cu(111) surfaces.

Besides the Cu(100) single-crystal series, some oxide-derived Cu catalysts have also shown a propensity for C2H4 and C2H5OH production8,9,10,15,16. For example, we have found that at −0.99 V vs. RHE, Cu films reduced from μm-thick Cu2O could catalyze the reduction of CO2 in 0.1 M KHCO3 electrolyte to C2H4 with FEs = 34–39%, while the FEs of CH4 were minimized to <1%9. Interestingly, thick oxide-derived Cu films, which do not appear to have very different morphological and chemical differences as the aforementioned C2-selective catalysts, have also been independently reported to be selective toward the formation of CO and HCOO−5,6. The selective reduction of CO2 to CH4 on Cu surfaces has been relatively less studied. Recently, Manthiram et al. reported that 7 nm-sized Cu nanoparticles dispersed on a glassy carbon electrode could catalyze the formation of CH4 with an average FE of 80% in 0.1 M NaHCO3 at −1.25 V vs. RHE7.

Based on characterizations of the catalysts presented in the above reports, the underlying causes for the selective reduction of CO2 to various products on Cu catalysts have been attributed to factors such as morphology9, particle sizes17,18, crystallite sizes and facets (for example, Cu(100))18, grain boundaries19, strains20, presence of residual oxygen (or Cu+)10,21, and rise in local pH at the surface of the electrode8. However, the effect of applied potential on the selectivity of these catalysts, as shown earlier by Peterson and Nørskov has been largely neglected or sidestepped in these important works12.

Here, we address this inadequacy by studying a series of Cu catalysts (metallic film and oxide-derived films) with different roughness factors for the electroreduction of CO2. We find that the selectivities of CO2 reduction toward HCOO−/CO, C2H4, and CH4 are observed to occur at different potential windows, as long as the mass transport limitation of CO2 is not reached. Furthermore, this finding can be used to explain the selectivities exhibited by a range of Cu single-crystal surfaces and nanostructures. We also discuss the role of oxide in oxide-derived Cu catalysts for the enhanced formation of CO, HCOO−, and C2H4.

Results

Characterization of the catalysts

The copper catalysts were prepared via electrodeposition22. By tuning the pH of the electrolyte and the deposition time, four different films were deposited (Supplementary Figure 1). These catalysts were characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), selected area electron diffraction (SAED, with transmission electron microscopy, TEM), and Raman spectroscopy (Fig. 1). As shown by their SAED patterns, 10 min depositions using pH = 10.5 electrolyte led to the formation of metallic Cu films (Cu-10), while the other three catalysts deposited using pH = 13.2 electrolyte for 1 min, 10 min, and 60 min were all CuO (termed as CuO-1, CuO-10, and CuO-60, respectively). The morphologies of the four films before and after CO2 reduction were revealed by SEM. The surface of Cu-10 consisted of μm-sized particles before reduction (Fig. 1a). The surfaces of CuO-1, CuO-10, and CuO-60 were covered with 10–100 nm particles, though the nanoparticles of CuO-60 agglomerated as μm-sized particles (Fig. 1b–d). After reduction, there was no significant morphology change for all four catalysts (Fig. 1e–h). The roughness factors (RFs) of post-reduced Cu-10, CuO-1, CuO-1, and CuO-60 were estimated by the double layer capacitance method to be 1.4, 5, 48, and 186, respectively (Supplementary Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 1).

Material characterization of four catalysts. SEM images and SAED patterns (inserts) of (a) Cu-10, (b) CuO-1, (c) CuO-10, and (d) CuO-60 catalysts before reduction; SEM images of (e) Cu-10, (f) CuO-1, (g) CuO-10, and (h) CuO-60 catalysts after reduction; (i) Raman spectra of Cu oxide surfaces collected ex situ and (j) operando Raman spectroscopy with the simultaneously obtained chronoamperogram of CuO-60 during CO2 reduction in 0.1 M KHCO3 at −0.5 V vs. RHE. Scale bars: 1 μm for SEM (a–g) and 5 nm−1 for SAED (inserts of a–d)

The Raman spectra of the three CuO films exhibited peaks at 293, 308, 338, and 610 cm−1, which could be assigned to signals from CuO (Fig. 1i)22,23. According to the Pourbaix diagram of the Cu-H2O system, the three CuO samples would be reduced to the metallic state under CO2 reduction potentials, i.e., potentials more negative than −0.50 V vs. RHE (all potentials cited in this work are referenced to the RHE)24. This was further verified by operando Raman spectroscopy of the catalysts (representative data for CuO-60 in Fig. 1j). Upon application of an electrochemical potential of −0.50 V vs. RHE, the 293, 338, and 610 cm−1 peaks of CuO disappeared within 140 s. From 140 s onward, three bands at 280, 360, and 2090 cm−1 appeared. These can be, respectively, assigned to the restricted rotation of bound CO, the Cu-CO stretching and C≡O stretching modes25,26,27. These bands were also observed on CuO-60 at more negative potentials from −0.60 to −0.80 V (Supplementary Figure 3), where hydrocarbons such as C2H4 were formed with appreciable quantities (FEethylene = 3–19%). This observation is consistent with previous reports that indicates CO is a key intermediate formed during the reduction of CO2 to hydrocarbons on Cu catalysts13,28. The appearance of Cu–CO signals only after the CuO signals have disappeared indicates that the active sites for CO2 reduction are likely to be metallic Cu. The reduction of oxide is also indicated by the chronoamperogram, which showed a reduction peak in the first 100 s (Fig. 1j).

The effects of limiting currents and applied potentials on CO2 reduction activity

The electrochemistry of our four catalysts toward CO2 reduction was assessed using 60 min chronoamperometry in aqueous 0.1 M KHCO3 electrolyte. A three-electrode setup29 was used and the products were quantified using gas chromatography and high performance liquid chromatography2.

The total current density and CO2 reduction current density are presented in Fig. 2a, b. In general, the total current densities exhibited by the catalysts correlated positively with the latters’ roughness factors and with the overpotentials applied. However, the CO2 reduction current densities on the four catalysts exhibited parabolic-like trends against the applied potentials, with maxima of about −20 mA cm−2. These maxima corresponded to total current densities of about −40 mA cm−2. Beyond the limiting total current density, the CO2 reduction current densities decreased and the selectivity toward H2 production increased. The limiting CO2 current can be attributed to the mass transport limitation of CO2 to the electrode, as CO2 has a poor solubility in aqueous electrolytes (~34 mM at 25 °C). Additionally, as the total current increased with applied overpotentials, there will also be a buildup of OH− near the electrode surface, i.e., an increase in local pH. This will cause a decrease in local concentration of CO2 near the electrode surface, resulting in the fall in CO2 reduction currents30,31. These findings are supported by numerical simulations of the concentrations of CO2 and local pH values at the Cu surface (using Cu-10 as the model; Supplementary Figure 4). As the simulated current increased to −90 mA cm−2, the local pH increased from a bulk value of 6.8 to 11.5, while the local CO2 concentration fell from 34 mM to 6.5 mM 32.

Electrocatalytic performance of four catalysts toward carbon dioxide electroreduction. a Total geometric current density and b current density for CO2 reduction (CO2R) on four catalysts at different potentials; c faradaic efficiency of methane on Cu-10 and CuO-1 catalysts at different potentials; d faradaic efficiency of ethylene and ethanol on CuO-1, CuO-10, and CuO-60 catalysts at different potentials; e faradaic efficiency of carbon monoxide and formate on CuO-60 catalyst at different potentials. Error bars in a–e represent the standard deviations of three independent measurements

The FEs of major CO2 reduction products are presented in Fig. 2c–e (Supplementary Tables 2-5). We found that a slightly roughened metallic Cu surface (Cu-10, RF = 1.4) exhibited excellent CH4 selectivity at −1.2 V with FEmethane of 62%. The oxide-derived Cu surfaces (CuO-1, RF = 5; CuO-10, RF = 48, and CuO-60, RF = 186) were generally more selective for C2H4 and C2H5OH (up to total FE of 48%)9,19. Interestingly, CuO-1 also exhibited a good selectivity toward CH4 at −1.15 V with a FE of 40%. This observation appears unusual as oxide-derived Cu films are hitherto not known to be selective toward the formation of CH45,9. We also note that the roughest sample, CuO-60, gave relatively high selectivities for CO and HCOO− at low overpotentials (FECO = 46% at −0.50 V and FEformate = 35% at −0.60 V).

Another observation is that the catalytic selectivity toward the formation of different products was only observed in specific potential ranges. At potentials more positive than −0.7 V, CO and HCOO− (maximum total FE = 75% at −0.55 V) were significantly formed. From −0.8 to −1.1 V, C2H4 and C2H5OH were produced in great quantities by all the CuO catalysts. As the overpotential increased further (more negative than −1.1 V), CH4 was selectively produced (high CH4 selectivity on Cu-10 at −1.15 V and CuO-1 at −1.2 V). Only small amounts of CH4 were produced using CuO-10 and CuO-60. This is likely because their total current density exceeded the limiting current density of −40 mA cm−2 after the potential reached more negative to −1.1 V, which caused significant decrease of the CO2 concentration near the electrode.

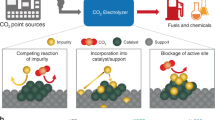

Proposed mechanism for the formation of major C1 and C2 products

Considering the electrocatalytic properties of different Cu catalysts and the DFT calculations reported in the literature12,33,34,35,36, we propose a mechanism for the formation of major C1 and C2 products (Fig. 3). After one proton and one electron transfer, CO2 could be reduced to either *OCHO or *COOH intermediate. Further reduction of *OCHO and *COOH lead to the respective formation of HCOO− and *CO. The presence of *CO as an intermediate species of CO2 reduction is demonstrated by our operando Raman spectroscopy results in Fig. 1j and Supplementary Figure 3. In agreement with previous studies on a range of Cu catalysts, we found that the potential-dependent profile of HCOO−’s faradaic efficiency does not exactly follow that of CO on CuO-60 (Fig. 2e)4,5,6,9. This indicates that CO and HCOO− may not have been formed through the same *COOH intermediate34,36. This finding is consistent with recent DFT calculations, which shows that the activities of a range of metallic catalysts toward HCOO− formation correlate better with their binding energies to *OCHO intermediates36. *CO could be further reduced to CH4, or undergo C–C coupling with another *CO to form C2H4 and C2H5OH. It is notable that to-date copper is the only metal electrode capable of facilitating these value-added reactions at reasonable rates as *CO is optimally bonded to it (Cu resides near the top of the volcano plot)37. We have also recently proposed a CO-insertion mechanism for the formation of C2H5OH in a CO rich environment11. The different energy barriers in the multiple pathways to form CO, HCOO−, C2H4, C2H5OH, and CH4 could be the reason why these products were observed at different potential windows (Fig. 2c–e)38.

Proposed mechanism for carbon dioxide electroreduction. a The pathway to C1 products (formate, carbon monoxide, and methane) and b the pathway to C2 products (ethylene and ethanol). Water molecules are not drawn and the formation of C2 products is drawn from carbon monoxide. Purple color indicates a free C1 molecule and orange color indicates a free C2 molecule

Discussion

On the basis of the preceding results, we propose here that the effects of tuning the morphology of a Cu catalyst may not solely lie in creating catalytically active sites (as commonly believed)9,39,40,41, but also affects its roughness so that the material operates with a suitable current density at a particular potential. Here, we discuss this proposition in conjunction with previous works (Fig. 4, Supplementary Tables 6 and 7). In Hori’s classic work, a constant current of −5 mA cm−2 was applied during CO2 reduction on all the Cu single crystals14,42. Under these conditions, Cu(100) and Cu(111) were, respectively, more selective for C2H4 and CH4 formation. Introducing (110) atomic steps to Cu(100) terraces to create high index surfaces was shown to further enhance C2H4 selectivity. These studies suggest that surface crystallography is paramount in the control of product selectivity. However, two recent CO2 reduction studies performed at various potentials (−0.30–−1.25 V by our group and −0.89–−1.15 V by Hahn et al.) revealed that Cu(100) could also reduce CO2 to CH4 with FE of 30–44% at about −1.1 V (Fig. 4a)43,44. It is remarkable that the enhanced selectivities for CH4, C2H4, and HCOO− formation (the formation of CO is generally <15% in these studies) on all the surfaces studied are most pronounced in distinct potential ranges. At potentials negative or equal to −1.1 V, CH4 selectivity was enhanced and the faradaic efficiency of C2H4 was low on Cu(111) and Cu(100). At potentials more positive than −1.0 V, C2H4 selectivity was observed and the FE of CH4 was suppressed to <10%, including on Cu(111). High faradaic efficiencies (FE) of HCOO− were observed at potentials more positive to −0.9 V on single crystals, especially on Cu(110). These evidences indicate that the applied potential is a crucial factor for the selectivities of different Cu single crystals. The corollary is that the frequently generalized statement ‘enhanced CH4 selectivity using Cu(111)’ or ‘enhanced C2H4 selectivity using Cu(100)’ is only true under specific conditions14,41,42.

Potential windows for the selective formation of different products. a Faradaic efficiency of ethylene, methane, and formate on different copper single crystals at different potentials from ref. 43 (wine) and ref. 44 (cyan). b The selectivities of 20 different Cu catalysts reported by 11 different research groups at different applied potentials. (1) isolated particles—ref. 7; (2) Cu-10 in this work; (3) polycrystalline—ref. 9 ; (4) polycrystalline—ref. 4; (5) Cu2O (3 C cm−2)—ref. 8; (6) 44 nm cubes—ref. 47; (7) nanoparticles—ref. 45; (8) KF roughened Cu—ref. 46; (9) electrochemically cycled Cu—ref. 31; (10) Cu2O (1.7 μm)—ref. 9; (11) mesocrystals—ref. 40; (12) CuO-10 in this work; (13) nanocrystals (Cu-NC10)—ref. 45; (14) Cu2O (O2 plasma 20 min—ref. 10; (15) nanocrystals (Cu-NC20)—ref. 45; (16) CuO nanowire—ref. 6; (17) CuO-60 in this work; (18) Cu2O (annealing)—ref. 5; (19) Cu2O (11 C cm-2)—ref. 8; (20) CuO nanoparticles—ref. 48

Besides Cu single crystals, we found that the selectivities of 20 other copper catalysts including metallic nanoparticles, oxide-derived nanoparticles, nanorods, etc. were also greatly affected by the applied potentials (Fig. 4b). To achieve a high selectivity of CH4 on catalysts, such as isolated Cu nanoparticles7, polycrystalline Cu4,13, as well as Cu-10 in this study, the applied potential was always more negative than −1.1 V (solid circles). Note that these catalysts have relatively smooth surfaces and as such, do not exhibit current density that exceeds −40 mA cm−2 (the limiting current density) at negative potentials ~−1.2 V. For catalysts that favor C2H4 formation such as Cu2O films8,9,10, Cu nanoparticles45, Cu nanocubes31,40,46,47, Cu nanocrystals45, and CuO films in this study, the optimum potential range was from −0.9 to −1.1 V (solid squares). CO and HCOO− selectivity were usually observed on rough and thick oxide-derived Cu films at potentials positive to −0.7 V5,6,8,10,45,48.

Hence, the top three regions in Fig. 4b (from left to right) indicates the most suitable potential ranges for the selective formation of CH4, C2H4, and CO/HCOO−, which are, respectively, about <−1.1 V, −0.9 V to −1.1 V, and > −0.9 V. It is notable that outside their suitable potential windows, these products are usually produced with FE <15% (hollow shapes in the bottom three regions of Fig. 4b). For example, the FE of C2H4 using ‘ethylene-selective’ catalysts were <11% at potentials negative to −1.1 V or positive to −0.8 V (hollow squares). We note here that the selectivities of some catalysts could not be clearly defined at the potentials interfacing two potential windows, such as at −0.90 V. For instance, apart from catalyzing the reduction of CO2 to C2H4 at −0.90 V (FE = 15%), CuO-1 could also catalyze the formation of HCOO− with an appreciable faradaic efficiency of ~20%. However, its selectivity toward HCOO− is lower compared with that of the thicker films (HCOO− forms at a FE of 35 % on CuO-60 at −0.60 V).

The potential windows highlighted in Fig. 4 are applicable to reports where the surfaces of the catalysts were particulate or planar, the electrolysis cell was similar to the design of Kuhl et al4 and the electrolyte was aqueous 0.1 M KHCO3 or other similar electrolytes (such as 0.1 M NaHCO3). Studies using significantly different cell designs49, gas diffusion electrodes16, nanoneedles, or nanofoams50 may exhibit different potential ranges for a specific product since these systems may have higher limiting current densities. The use of KOH or KCl electrolytes16,51 may introduce other effects such as high local pH, and thus, do not fit properly in the above-defined regions.

The aforementioned potential windows (Fig. 4) also show that the DFT predictions made by Peterson and Nørskov on how potentials affect product selectivity is not only applicable to Cu(211) surfaces12, but can also be applied to a variety of Cu catalysts such as Cu single crystals, oxide-derived Cu and Cu nanostructures, as long as mass transport limitation of CO2 has not been reached.

It is interesting that CuO-1, an oxide, exhibited a surprisingly high faradaic efficiency of CH4 (Fig. 2c). In fact, from −0.95 to −1.15 V, the FE of CH4 on CuO-1 (3–40%) and Cu-10 (2–54%) are comparable. This observation is remarkable because oxidized Cu catalysts are known for their propensity to reduce CO2 to C2 products, rather than to CH48,9,10. Hence, this result indicates that the presence of oxide is not the most crucial factor in determining selectivity between CH4 and C2H4. We further note that an electropolished Cu surface would be oxidized once exposed to air (which is almost inevitable during sample transfer) and yet, this catalyst is known to produce high FE of CH4 at negative potentials (Fig. 4b)4.

An insight could also be gained from the selectivities exhibited by oxide-derived Cu catalysts reported by many groups, including Kanan, Baltrusaitis, and ours5,6,8,9,31,48. These films have been reported selective toward the reduction of CO2 to either HCOO− or C2–C3 products. This behavior is intriguing if we consider that the chemical identities and morphologies (in the nanometer scale) of these films do not appear very different8. For example, using a thick layer of Cu oxide (prepared by annealing a Cu foil at 500 °C for 12 hours), Kanan et al. reported FEs of 47% for CO and 39% for HCOO− at −0.35 and −0.55 V, respectively. C2H4 was formed at a maximum FE of only ~5% at −0.95 V5. The production of C2H4 is, thus, notably lower than that on a polycrystalline Cu surface (FE = 23% at −0.97 V) and our oxide-derived Cu films (34–39% at −0.99 V)9,13. The fact that Kanan’s Cu sample exhibited rather low selectivities toward C2H4 seem to contradict with observations made by Baltrusaitis et al. and our group. We propose here a simple explanation for this observation: apart from the slightly different electrolytes used, we highlight that the high total current density (about −25 mA cm−2) exhibited by Kanan’s annealed Cu at −0.95 V will result in a lower local concentration of CO2 near the electrode surface. This will cause an overall lowering of the FE for CO2 reduction and consequently, a decreased formation of C2H4 at −0.95 V. Our observation indicates that thick oxide films will not be suitable for C2H4/C2H5OH formation, once their roughness factors exceed the optimum9.

Schouten and Koper have measured the onset potentials required for the formation of CH4 and C2H4 during CO reduction on Cu(100) and Cu(111) electrodes52,53. It was shown that C2H4 could be formed at ~400 mV lower overpotential compared to CH4 on Cu(100) in pH = 7 electrolyte. C2H4 was further proposed to be formed via a CO dimerization pathway on Cu(100). Although this study had revealed the potential-dependence of C2H4 formation on Cu(100), we draw here a more general trend of how the electrochemical potential affects the selectivity of CO2 reduction for a wide range of Cu surface structures. The effect of limiting current density on selectivities is also addressed here.

Finally, our work highlights how we could design Cu catalysts with various selectivities—it is critical to control the surface roughness such that the limiting current density lies in the suitable potential window for CH4, C2H4, or CO/HCOO−. In order to achieve a high selectivity of CH4 formation, the catalyst should be relatively smooth so that the limiting current density is not exceeded at the very negative applied potentials needed (i.e., more negative than −1.2 V). With a roughness factor of 1.4, Cu-10 catalyst exhibits both high faradaic efficiency (62%) and high partial current density (−18 mA cm−2) of CH4, making it among the best catalysts toward CH4 formation7. For C2H4 and C2H5OH selectivity, the catalyst should have a slightly roughened surface so that the intermediates are stabilized and its CO2 reduction current density is maximized at regions from −0.9 V to −1.1 V. To obtain a high faradaic efficiency of CO or HCOO−, the catalysts should be thick and rough oxide-derived films with high RFs. We note here that though smooth surfaces such as Cu(110), polycrystalline Cu, and Cu-10 could catalyze the reduction of CO2 to HCOO− or CO at more negative potentials, their selectivities are not comparable with those exhibited by thick Cu oxide films at less negative potentials13,43.

In this work, we prepared four Cu-based films by electrodeposition, and showed that they exhibited different selectivities toward CO2 reduction at different potential ranges. We highlight how limiting currents and applied potentials affect the selectivity of CO2 reduction reactions. This helps to rationalize the selectivity of different Cu catalysts, not only in this work, but also from many other reports. A FE of ~40% of CH4 observed on CuO-1 film at −1.15 V contradicts with a proposition that Cu+ or subsurface oxygen-modified Cu is the preferred catalyst for C2H4 selectivity. This study strongly shows that optimization of CO2 reduction current densities at the appropriate potential windows is critical for forming the type of product needed, and thus provides us with insights into how highly selective Cu catalysts could be rationally designed.

Methods

Preparation of electrocatalysts

The substrates were mechanically polished Cu discs (99.99%, Goodfellow) with an exposed geometric surface area of 0.865 cm2. Two aqueous deposition electrolytes, A and B were prepared, for the depositions of metallic and oxide films, respectively.

Electrolyte A was prepared by first dissolving tartaric acid (Alfa Aesar, 99%) in deionized water (18.2 MΩ cm, Barnstead Type 1). CuSO4 5H2O (GCE, 99%) was then added. The solution was then cooled and continuously stirred in an ice water bath while NaOH (Chemicob, 99%) was slowly added. The final pH of the solution was 10.5, with the concentrations of tartaric acid, CuSO4 5H2O and NaOH at, respectively, 0.2, 0.2, and 0.8 M. The deposition of Cu-10 was carried out in a two-electrode setup with a Pt wire as the counter electrode. Chronopotentiometry at 8 mA cm−2 for 10 min was used for the deposition of Cu-10.

Electrolyte B was prepared similarly as above except that it had 2.5 M NaOH, resulting in a pH 13.2 solution. The deposition of CuO-1 was carried out in a three-electrode setup with a Pt wire and a Ag/AgCl (Saturated KCl, Pine) as the counter and reference electrodes, respectively. Chronamperometry at 1.47 V vs. RHE for 1 min (Autolab PGSTAT30) was used for the deposition of CuO-1. The deposition of CuO-10 and CuO-60 were carried out in a two-electrode setup with a Pt wire as the counter electrode. CuO-10 and CuO-60 were deposited by applying 8 mA cm−2 for 10 min and 60 min, respectively[22].

Characterization of the electrocatalysts

The chemical compositions of the catalysts were characterized using SAED (SAED, TEM mode, JEOL 3010, 300 kV, 112 μA) and Raman spectroscopy (Modular System, Horiba Jobin Yvon). A He–Ne laser was used as the excitation source and the acquisition time was 10 seconds for each spectrum. A dry objective (Olympus MPlan N, 50×, numerical aperture = 0.75) and a water immersion objective (Olympus LUMFL, 60×, numerical aperture = 1.10) were, respectively, employed for ex situ and operando Raman spectroscopy. The morphologies of the catalysts were characterized by SEM (JEOL JSM-6710F, 5 kV). Their electrochemical-active surface areas were determined by their double layer capacitances in N2-saturated 0.1 M KClO4 (99.9%, Sigma Aldrich). A three-electrode setup was used with a Pt wire counter and a Ag/AgCl reference electrode (Saturated KCl, Pine). Cyclic voltammetry were performed in a non-faradaic region from −0.05 V to 0.05 V vs. RHE. The scan rates were 50, 100, 150, 200, 250, 300, 350, and 400 mV s−1.

Electrochemical reduction of CO2

CO2 electroreduction was performed in a custom built three-electrode electrochemical cell45. The reference and counter electrodes were, respectively, a Ag/AgCl (saturated KCl, Pine) and a coiled Pt wire. The cathodic and anodic compartments were separated by an anion exchange membrane (Asahi Glass). Both compartments were filled with CO2-saturated 0.1 M KHCO3 (99.7%, Merck). During 60 min chronoamperometry, 20 cm3 min−1 of CO2 was continuously flowed into the electrolyte. The gas outlet of cathodic compartment was connected to a gas chromatograph (GC, Agilent 7890A) for the online quantification of gas products. The liquid products were quantified by headspace gas chromatography (HS-GC, Agilent 7890B) and high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC, Agilent 1260) after electrolysis. The voltage drop was automatically compensated using the current-interrupt mode available in the potentiostat (Gamry 600). The voltage was converted to the RHE scale and the current density was normalized to the exposed geometric surface area. All the detected products were quantified in terms of their FE. The FE of product X is defined as:

Each reported FE value was the average of three independent sets of measurements.

Numerical simulations of local pH and CO2 concentration

Numerical simulations were performed with MATLAB 8.5 to calculate the local pH and how the concentration of CO 2 near the electrode changed as a function of current density32. The electrode was taken to be planar (1-D model). The corresponding bulk concentration of CO2, HCO3−, CO32−, and H+, diffusion coefficients, and rate constants were taken from the work of Gupta et al., along with the boundary conditions32. The diffusion layer thickness was assumed to be 36 μm54. The normalized current density (against the electrochemical-active surface area) and the FE were used for calculations18. Only the effect of diffusion and surface reaction were considered in this model. Only the Cu-10 surface was simulated as it has a small roughness factor of 1.4, and, thus, its surface is close to planar.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors.

References

Aresta, M., Dibenedetto, A. & Angelini, A. Catalysis for the valorization of exhaust Carbon: from CO2 to chemicals, materials, and fuels. technological use of CO2. Chem. Rev. 114, 1709–1742 (2013).

Ren, D., Loo, N. W. X., Gong, L. & Yeo, B. S. Continuous production of ethylene from carbon dioxide and water using intermittent sunlight. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 5, 9191–9199 (2017).

Hori, Y., Wakebe, H., Tsukamoto, T. & Koga, O. Electrocatalytic process of CO selectivity in electrochemical reduction of CO2 at metal electrodes in aqueous media. Electrochim. Acta 39, 1833–1839 (1994).

Kuhl, K. P., Cave, E. R., Abram, D. N. & Jaramillo, T. F. New insights into the electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide on metallic copper surfaces. Energy Environ. Sci. 5, 7050–7059 (2012).

Li, C. W. & Kanan, M. W. CO2 Reduction at low overpotential on Cu electrodes resulting from the reduction of thick Cu2O films. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 7231–7234 (2012).

Ma, M., Djanashvili, K. & Smith, W. A. Selective electrochemical reduction of CO2 to CO on CuO-derived Cu nanowires. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17, 20861–20867 (2015).

Manthiram, K., Beberwyck, B. J. & Alivisatos, A. P. Enhanced electrochemical methanation of carbon dioxide with a dispersible nanoscale copper catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 13319–13325 (2014).

Kas, R. et al. Electrochemical CO2 Reduction on Cu2O-derived copper nanoparticles: controlling the catalytic selectivity of hydrocarbons. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 12194–12201 (2014).

Ren, D. et al. Selective electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide to ethylene and ethanol on copper(I) oxide catalysts. ACS Catal. 5, 2814–2821 (2015).

Mistry, H. et al. Highly selective plasma-activated copper catalysts for carbon dioxide reduction to ethylene. Nat. Commun. 7, 12123 (2016).

Ren, D., Ang, B. S.-H. & Yeo, B. S. Tuning the selectivity of carbon dioxide electroreduction toward ethanol on Oxide-Derived CuxZn catalysts. ACS Catal. 6, 8239–8247 (2016).

Peterson, A. A., Abild-Pedersen, F., Studt, F., Rossmeisl, J. & Nørskov, J. K. How copper catalyzes the electroreduction of carbon dioxide into hydrocarbon fuels. Energy Environ. Sci. 3, 1311–1315 (2010).

Hori, Y., Murata, A. & Takahashi, R. Formation of hydrocarbons in the electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide at a copper electrode in aqueous solution. J. Chem. Soc., Faraday Trans. 1 85, 2309–2326 (1989).

Hori, Y., Takahashi, I., Koga, O. & Hoshi, N. Electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide at various series of copper single crystal electrodes. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 199, 39–47 (2003).

Kim, D. et al. Insights into an autonomously formed oxygen-evacuated Cu2O electrode for the selective production of C2H4 from CO2. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17, 824–830 (2015).

Ma, S. et al. One-step electrosynthesis of ethylene and ethanol from CO2 in an alkaline electrolyzer. J. Power Sources 301, 219–228 (2016).

Reske, R., Mistry, H., Behafarid, F., Roldan Cuenya, B. & Strasser, P. Particle size effects in the catalytic electroreduction of CO2 on Cu nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 6978–6986 (2014).

Handoko, A. D. et al. Mechanistic insights into the selective electroreduction of carbon dioxide to ethylene on Cu2O-Derived copper catalysts. J. Phys. Chem. C. 120, 20058–20067 (2016).

Verdaguer-Casadevall, A. et al. Probing the active surface sites for CO reduction on Oxide-Derived copper electrocatalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 9808–9811 (2015).

Li, C. W., Ciston, J. & Kanan, M. W. Electroreduction of carbon monoxide to liquid fuel on oxide-derived nanocrystalline copper. Nature 508, 504–507 (2014).

Eilert, A. et al. Subsurface oxygen in Oxide-Derived copper electrocatalysts for carbon dioxide reduction. J. Phy. Chem. Lett. 8, 285–290 (2017).

Deng, Y., Handoko, A. D., Du, Y., Xi, S. & Yeo, B. S. In situ raman spectroscopy of copper and copper oxide surfaces during electrochemical oxygen evolution reaction: identification of CuIII oxides as catalytically active species. ACS Catal. 6, 2473–2481 (2016).

Chen, X. K., Irwin, J. C. & Franck, J. P. Evidence for a strong spin-phonon interaction in cupric oxide. Phys. Rev. B 52, R13130 (1995).

Beverskog, B. & Puigdomenech, I. Revised Pourbaix diagrams for copper at 25 to 300 C. J. Electrochem. Soc. 144, 3476–3483 (1997).

Akemann, W. & Otto, A. Vibrational modes of CO adsorbed on disordered copper films. J. Raman Spectrosc. 22, 797–803 (1991).

Oda, I., Ogasawara, H. & Ito, M. Carbon monoxide adsorption on copper and silver electrodes during carbon dioxide electroreduction studied by infrared reflection absorption spectroscopy and surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Langmuir 12, 1094–1097 (1996).

Smith, B., Irish, D., Kedzierzawski, P. & Augustynski, J. A surface enhanced raman scattering study of the intermediate and poisoning species formed during the electrochemical reduction of CO2 on copper. J. Electrochem. Soc. 144, 4288–4296 (1997).

Hori, Y., Murata, A. & Yoshinami, Y. Adsorption of CO, intermediately formed in electrochemical reduction of CO2, at a copper electrode. J. Chem. Soc., Faraday Trans. 87, 125–128 (1991).

Chen, C. S., Wan, J. H. & Yeo, B. S. Electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide to ethane using nanostructured Cu2O-Derived copper catalyst and Palladium (II) chloride. J. Phys. Chem. C. 119, 26875–26882 (2015).

Singh, M. R., Kwon, Y., Lum, Y., Ager, J. W. & Bell, A. T. Hydrolysis of electrolyte cations enhances the electrochemical reduction of CO2 over Ag and Cu. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 13006–13012 (2016).

Lum, Y., Yue, B., Lobaccaro, P., Bell, A. T. & Ager, J. W. Optimizing C–C coupling on Oxide-Derived copper catalysts for electrochemical CO2 reduction. J. Phys. Chem. C. 121, 14191–14203 (2017).

Gupta, N., Gattrell, M. & MacDougall, B. Calculation for the cathode surface concentrations in the electrochemical reduction of CO2 in KHCO3 solutions. J. Appl. Electrochem. 36, 161–172 (2005).

Durand, W. J., Peterson, A. A., Studt, F., Abild-Pedersen, F. & Nørskov, J. K. Structure effects on the energetics of the electrochemical reduction of CO2 by copper surfaces. Surf. Sci. 605, 1354–1359 (2011).

Schouten, K., Kwon, Y., Van der Ham, C., Qin, Z. & Koper, M. A new mechanism for the selectivity to C1 and C2 species in the electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide on copper electrodes. Chem. Sci. 2, 1902–1909 (2011).

Calle-Vallejo, F. & Koper, M. T. M. Theoretical considerations on the electroreduction of CO to C2 species on Cu(100) electrodes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 7282–7285 (2013).

Feaster, J. T. et al. Understanding selectivity for the electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide to formic acid and carbon monoxide on metal electrodes. ACS Catal. 7, 4822–4827 (2017).

Seh, Z. W. et al. Combining theory and experiment in electrocatalysis: insights into materials design. Science 355, eaad4998 (2017).

Kortlever, R., Shen, J., Schouten, K. J. P., Calle-Vallejo, F. & Koper, M. T. M. Catalysts and reaction pathways for the electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide. J. Phy. Chem. Lett. 6, 4073–4082 (2015).

Tang, W. et al. The importance of surface morphology in controlling the selectivity of polycrystalline copper for CO2 electroreduction. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 14, 76–81 (2012).

Chen, C. S. et al. Stable and selective electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide to ethylene on copper mesocrystals. Catal. Sci. Technol. 5, 161–168 (2015).

Roberts, F. S., Kuhl, K. P. & Nilsson, A. High selectivity for ethylene from carbon dioxide reduction over copper nanocube electrocatalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 5179–5182 (2015).

Takahashi, I., Koga, O., Hoshi, N. & Hori, Y. Electrochemical reduction of CO2 at copper single crystal Cu (S)-[n(111)×(111)] and Cu (S)-[n(110)×(100)] electrodes. J. Electroanal. Chem. 533, 135–143 (2002).

Huang, Y., Handoko, A. D., Hirunsit, P. & Yeo, B. S. Electrochemical reduction of CO2 using copper single-crystal surfaces: effects of CO* coverage on the selective formation of ethylene. ACS Catal. 7, 1749–1756 (2017).

Hahn, C. et al. Engineering Cu surfaces for the electrocatalytic conversion of CO2: controlling selectivity toward oxygenates and hydrocarbons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 5918–5923 (2017).

Ren, D., Wong, N. T., Handoko, A. D., Huang, Y. & Yeo, B. S. Mechanistic insights into the enhanced activity and stability of agglomerated Cu nanocrystals for the electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide to n-propanol. J. Phy. Chem. Lett. 6, 20–24 (2016).

Kwon, Y., Lum, Y., Clark, E. L., Ager, J. W. & Bell, A. T. CO2 Electroreduction with enhanced ethylene and ethanol selectivity by nanostructuring polycrystalline copper. ChemElectroChem. 3, 1012–1019 (2016).

Loiudice, A. et al. Tailoring copper nanocrystals towards C2 products in electrochemical CO2 reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 5789–5792 (2016).

Gupta, K., Bersani, M. & Darr, J. A. Highly efficient electro-reduction of CO2 to formic acid by nano-copper. J. Mat. Chem. A 4, 13786–13794 (2016).

Ma, S. et al. Electroreduction of carbon dioxide to hydrocarbons using bimetallic Cu–Pd catalysts with different mixing patterns. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 47–50 (2017).

Burdyny, T. et al. Nanomorphology-enhanced gas-evolution intensifies CO2 reduction electrochemistry. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 5, 4031–4040 (2017).

Lee, S., Kim, D. & Lee, J. Electrocatalytic production of C3‐C4 Compounds by conversion of CO2 on a chloride‐induced bi‐phasic Cu2O‐Cu catalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 14701–14705 (2015).

Schouten, K. J. P., Pérez Gallent, E. & Koper, M. T. M. The influence of pH on the reduction of CO and to hydrocarbons on copper electrodes. J. Electroanal. Chem. 716, 53–57 (2014).

Schouten, K. J. P., Qin, Z., Gallent, E. P. & Koper, M. T. M. Two pathways for the formation of ethylene in CO reduction on Single-crystal copper electrodes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 9864–9867 (2012).

Bumroongsakulsawat, P. & Kelsall, G. H. Effect of solution pH on CO: formate formation rates during electrochemical reduction of aqueous CO2 at Sn cathodes. Electrochim. Acta 141, 216–225 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by a research grant, R-143-000-683-112, from the Ministry of Education, Singapore. D.R. acknowledges a Ph.D. research scholarship from the Ministry of Education, Singapore. We thank Cheng Wai Ong (NUS) for performing the numerical simulations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.R., and B.S.Y. conceived the idea and designed the experiments. D.R., and J.F. ran the electrochemistry measurements. D.R. characterized the samples. B.S.Y. supervised the project. All the authors analyzed the data and contributed to the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ren, D., Fong, J. & Yeo, B.S. The effects of currents and potentials on the selectivities of copper toward carbon dioxide electroreduction. Nat Commun 9, 925 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-03286-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-03286-w

This article is cited by

-

Facilitating electrocatalytic CO2 reduction through electrolyte additives accompanied by activation of copper electrode with cyclic voltammetry

Ionics (2024)

-

Unlocking direct CO2 electrolysis to C3 products via electrolyte supersaturation

Nature Catalysis (2023)

-

High-rate and selective conversion of CO2 from aqueous solutions to hydrocarbons

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Trends in oxygenate/hydrocarbon selectivity for electrochemical CO(2) reduction to C2 products

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Steering surface reconstruction of copper with electrolyte additives for CO2 electroreduction

Nature Communications (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.