Abstract

The 13C/12C ratio of C3 plant matter is thought to be controlled by the isotopic composition of atmospheric CO2 and stomatal response to environmental conditions, particularly mean annual precipitation (MAP). The effect of CO2 concentration on 13C/12C ratios is currently debated, yet crucial to reconstructing ancient environments and quantifying the carbon cycle. Here we compare high-resolution ice core measurements of atmospheric CO2 with fossil plant and faunal isotope records. We show the effect of pCO2 during the last deglaciation is stronger for gymnosperms (−1.4 ± 1.2‰) than angiosperms/fauna (−0.5 ± 1.5‰), while the contributions from changing MAP are −0.3 ± 0.6‰ and −0.4 ± 0.4‰, respectively. Previous studies have assumed that plant 13C/12C ratios are mostly determined by MAP, an assumption which is sometimes incorrect in geological time. Atmospheric effects must be taken into account when interpreting terrestrial stable carbon isotopes, with important implications for past environments and climates, and understanding plant responses to climate change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

At present the global mean stable carbon isotope composition of C3 plants (δ13Cp), most of Earth’s vegetation, is about −27‰ relative to VPDB, although δ13C varies widely between about −22 and −36‰1. Understanding the sources of this variation has been the major aim of stable isotope studies of plant physiology and ecology2,3,4. Studies of modern plants1, 5 have found that although correlations exist with variables that include plant functional type and altitude, δ13Cp is most strongly correlated with mean annual precipitation (MAP). Values more positive than about −22‰ are found in arid and hyperarid regions, whereas values more negative than −31.5‰ are restricted to closed-canopy tropical forests. However, there is currently no accurate understanding of how plant δ13Cp varies with past atmospheric CO2 and climate. Nearly thirty years ago, a striking correspondence was first noted between a 4‰ change in the δ13Cp of North American trees and the deglacial rise in atmospheric CO2 concentration6. The difference, also identified in fossilised Pinus flexilis needles7 and Japanese conifers8, has been explained by changes in leaf water-use efficiency and stomatal conductance under conditions of changing pCO27, 9, 10, which are derived from classical models of photosynthetic fractionation11, 12. The complexity of these models is seemingly at odds with experimental data from plant growth chambers obtained by Schubert and Jahren13, who propose a simple alternative model which depends on changes in only two atmospheric variables, i.e. pCO2 and the source isotopic composition of carbon dioxide (δ13\({\mathrm{C}}_{{\mathrm{CO}}_{\mathrm{2}}}\)). According to this simple model, most of the global change in δ13Cp of fossil leaves and bulk terrestrial organic matter from the past 30 kyr14 can be explained by the deglacial rise in pCO2. This model has been disputed15 on two bases: first, that the change in δ13Cp can be completely explained by an increase in MAP, differential organic degradation, and changes in δ13\({\mathrm{C}}_{{\mathrm{CO}}_{\mathrm{2}}}\), and second, that fossil collagen and tooth enamel from the Eocene to the historical era apparently do not discern a pCO2 effect. On the other hand, globally averaged records of speleothem δ13C appear to support a strong pCO2 dependence over the past 90 kyr16, and the issue is thus unresolved.

An accurate model of the factors which control δ13Cp is of great importance for understanding CO2 exchange during glacial–interglacial cycles17, evaluation of palaeo-CO2 proxies for timescales beyond the ice-core record18, and investigating CO2 assimilation by the biosphere under future anthropogenic emissions19. There are also fundamental implications for palaeoecology. The average δ13C of modern C4 plants is around −12.5‰20, and the clear difference of ~14‰ between this and the values of C3 plants gained early recognition as an effective method of distinguishing between the two photosynthetic pathways21, 22. This difference is also passed onto animal tissues, forming the basis for reconstructions of the diets of ancient fauna and hominins20, 23, 24. Predictions from models of photosynthetic fractionation, however, suggest that C3 and C4 plants respond differently to changes in global pCO2, and the magnitude and timing of changes to δ13Cp of each group will differ. Knowing the details of δ13Cp response to changing atmospheric CO2 is therefore crucial in the interpretation of faunal stable isotope records as proxies of C3 and C4 vegetation cover in mixed environments in deep time25,26,27 as well as reconstructing environmental parameters such as MAP and/or forest cover in C3 settings28,29,30.

Here we address the issue by exploring the implications of changes in atmospheric δ13\({\mathrm{C}}_{{\mathrm{CO}}_{\mathrm{2}}}\) and pCO2 for δ13C proxies from terrestrial archives of carbon. We use recently published high-resolution data for δ13\({\mathrm{C}}_{{\mathrm{CO}}_{\mathrm{2}}}\) and pCO2 from Antarctic ice cores to compute predictions of δ13Cp under four different models of photosynthetic fractionation over the past 155 kyr. We then compare model predictions with two high temporal resolution compilations of δ13C from wood cellulose and faunal collagen which span the last deglaciation, to infer the relative magnitudes of changes due to MAP, pCO2 and δ13\({\mathrm{C}}_{{\mathrm{CO}}_{\mathrm{2}}}\).

Results

Photosynthetic fractionation over the last glacial cycle

First, we mathematically model the effects of shifts in pCO2 from 150 to 400 ppmv, over a range of relevant δ13\({\mathrm{C}}_{{\mathrm{CO}}_{\mathrm{2}}}\) (glacial maxima to present day) to demonstrate the potential magnitude and direction of changes in δ13Cp. We consider four models which represent different scenarios of plant physiological control on isotope fractionation (Supplementary Fig. 1) in C3 land plants. The first three models are based on the expression developed by Farquhar et al.11, 12, which combines fractionations associated with carboxylation and diffusion of CO2 into the leaf:

where a is the magnitude of fractionation during gaseous diffusion of CO2 through the lead boundary layer and stomata, and b is the magnitude of net discrimination during carboxylation in C3 plants. Both diffusion and carboxylation are dependent on the ratio of leaf intercellular to atmospheric partial pressures of CO2 (ci/ca).

Two of these models assume that ci/ca varies linearly with ca, but with different gradients for angiosperms and gymnosperms, which are called models “Voelker-2016a” and “Voelker-2016g” respectively (see Methods for details). Motivation for different leaf gas-exchange strategies in these two groups comes from analyses of modern experiments and fossil tree-ring data from the Last Glacial31, as well angiosperm leaf waxes and terpenoids from the Palaeogene32, which consistently show a 2‰ depletion in 13C relative to gymnosperm species. For comparison, another model (hereafter “Farquhar-1982”) assumes a leaf gas-exchange strategy where constant ci/ca is maintained across the entire range of pCO2, which is unlikely. Finally, we consider the hyperbolic model (SJ-2012) proposed by Schubert and Jahren13, which is based on the expression

where \({\mathrm{\Delta }}^{13}{\mathrm{C}} = \left( {\delta ^{13}{\mathrm{C}}_{{\mathrm{CO}}_2} - \delta ^{13}{\mathrm{C}}_{\mathrm{p}}} \right){\mathrm{/}}\left( {1 + \delta ^{13}{\mathrm{C}}_{\mathrm{p}}{\mathrm{/}}1000} \right)\), and A, B, and C are constants obtained by fitting Eq. (2) to data from modern growth chamber experiments conducted on Raphanus sativus and Arabidopsis plants, as well as fossil δ13Cp from the Last Glacial, which together provides a large range of pCO2 (180 to 4200 ppmv) and δ13\({\mathrm{C}}_{{\mathrm{CO}}_{\mathrm{2}}}\) (−6.4 to −18.0‰).

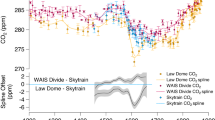

To identify the timing and magnitude of expected shifts in δ13Cp over the past 155 kyr, we compute the predictions of the four models using Antarctic ice core records of δ13\({\mathrm{C}}_{{\mathrm{CO}}_{\mathrm{2}}}\) and δ13\({\mathrm{C}}_{{\mathrm{CO}}_{\mathrm{2}}}\) (Supplementary Data 1). Our ice core compilation (Fig. 1) makes use of a recently published record33 which significantly improves the temporal resolution of δ13\({\mathrm{C}}_{{\mathrm{CO}}_{\mathrm{2}}}\) measurements between Terminations I and II, which are already well-represented. These pCO2 and δ13\({\mathrm{C}}_{{\mathrm{CO}}_{\mathrm{2}}}\) measurements present a near-continuous record, apart from the period between 47–43 kyr BP, where there is disagreement between EPICA Dronning Maud Land and Talos Dome cores.

Ice core records of stable carbon isotope composition and concentration of CO2 from 155 kyr BP to the present. a CO2 concentration data from the preindustrial era compiled from EPICA Dome C (EDC), Talos Dome, EPICA Dronning Maud Land (EDML), and Siple ice cores, with post-industrial records from Law Dome and South Pole. Black curve shows a Monte Carlo average (MCA) spline. b Corresponding δ13\({\mathrm{C}}_{{\mathrm{CO}}_{\mathrm{2}}}\) records and MCA spline. Error bars are 1σ uncertainties. Dark grey region is 1σ confidence interval for spline. Open circles indicate outliers identified by ref. 33. c Models of δ13Cp calculated from ice core records. SJ-2012 model (light green curve) is shown with 1σ propagated uncertainties. Blue bars indicate three periods where this model predicts a change in δ13Cp of more than 1‰ at a rate exceeding 0.25‰/kyr, excluding the period of recent anthropogenic change

All models, with the exception of Farquhar-1982, resolve a −2.5‰ change in δ13Cp due to the anthropogenic isotope effect, and offer similar predictions for future δ13Cp. However, it is important to note that the models diverge strongly under conditions of low pCO2. During the period between the Last Glacial and the beginning of the Holocene (11.4 kyr BP), ice cores document an 80 ppmv rise in pCO2, which is accompanied by fluctuations in δ13\({\mathrm{C}}_{{\mathrm{CO}}_{\mathrm{2}}}\) of up to 0.3‰ (Fig. 1). Over the same period, a change of similar magnitude (i.e. 0.3‰) is predicted in δ13Cp by Farquhar-1982, which assumes a negligible pCO2 effect. The Voelker-2016a and Voelker-2016g models predict a larger change in δ13Cp of −0.8‰ and −0.9‰, respectively. The largest change is predicted by SJ-2012 (−2.0‰), which is comparable to the recent anthropogenic isotope effect. This is a significant change which is larger than that implied by an hypothetical doubling in MAP (1‰)15, combined with any changes in δ13\({\mathrm{C}}_{{\mathrm{CO}}_{\mathrm{2}}}\) (<0.3‰) over the LGM/Holocene transition.

Furthermore, the SJ-2012 model predicts high amplitude changes (>1‰) in δ13Cp during three periods over the past 155 kyr (12–18, 60–62.7, and 129.4–135 kyr). These changes occur at a rate which exceeds 0.25‰/kyr (Fig. 1), excluding the past 130 years, where the change in δ13Cp is two orders of magnitude greater (40‰/kyr). The durations of the three pre-Industrial high-amplitude episodes range from 2.7 to 5.6 kyr, and are therefore relatively brief on Quaternary timescales. Interestingly, while two of these episodes can be attributed to the rise in pCO2 during both glacial terminations, the 1‰ shift in δ13Cp predicted by this model between 60 and 62.7 kyr is mainly driven by a 0.5‰ decrease in δ13\({\mathrm{C}}_{{\mathrm{CO}}_{\mathrm{2}}}\), which is accompanied by an increase in CO2 concentration occurring during Marine Isotope Stage (MIS) 433.

The rates and timings of these predicted changes need to be considered when evaluating the pCO2 effect from fossil archives. Previous examination of faunal collagen and tooth enamel from the Eocene to the present appears to show no pCO2 effect15. However, considering that our analysis shows that high amplitude changes in δ13Cp are predicted to occur during relatively brief periods (i.e. ~2.7–5.6 kyr), and faunal data from previous studies are thinly represented across several million years, it is unlikely that they provide the necessary temporal resolution to discern a possible pCO2 effect. In other words, beyond the limit of radiocarbon dating (~50 kyr), fossil archives will have minimum age uncertainties of several thousand years, which makes evaluation of the pCO2 effect impossible. Our analysis reveals that the only period during which the effect would be statistically distinguishable is the last deglaciation, when radiocarbon methods offer sufficient dating precision (~50–300 yr, 1σ).

Comparison with plant and faunal isotope archives

To test each model we compile a record of δ13Cp which is based on 720 samples of radiocarbon-dated wood cellulose from the Northern Hemisphere, spanning the last deglaciation (Fig. 2). We also compile 521 δ13C values of well-dated herbivore collagen from predominantly C3 locations in northwestern Europe and northern Eurasia. Since this compilation is biased towards these regions, and herbivore diets are selective, the faunal record will not always reflect the ‘average’ composition of plants in an ecosystem. Additionally, our cellulose data are over-represented by woody species from temperate northern latitudes. Therefore, to make these very widely dispersed samples comparable, we adopt a strategy of adjusting both cellulose and collagen δ13C records for geographical variability in latitude, altitude and MAP (see Methods). When we adjust for geographical variability in this way (Fig. 2) the amplitude of changes across the LGM/Holocene transition is reduced from 1.41 to 0.93‰ (fauna) and 3.54 to 2.77‰ (plants). Therefore, the residual effect appears different for both cellulose and collagen. Note that our faunal data show greater scatter than our cellulose records, but the shift in δ13C between <10 and >20 kyr faunal data is statistically significant (one-sided paired sample t-test, t = −5.9, p = 5.2 × 10−8, α = 0.05).

Stable carbon isotope composition of terrestrial fossil archives over the last deglaciation, from predominantly C3 ecosystems. a Faunal collagen from northwestern Europe and northern Eurasia from 33.4 kyr BP to early 20th century. Light red circles show δ13C before adjustment for MAP, altitude and latitude. Dark red circles show adjusted δ13C, based on the regressions of Kohn1. Dark black lines indicate adjusted means of faunal δ13C before 20 kyr and after 10 kyr, which are −20.85‰ and −21.78‰, respectively. b Plant cellulose δ13Cp records from the Northern Hemisphere, 40.5 kyr BP to early 20th century, with model curves. Colour codes match legend in Fig. 1: light green, SJ-2012; blue, Voelker-2016g; dashed yellow, Farquhar-1982. SJ-2012 model is shown with 1σ propagated uncertainties. Dark blue squares show gymnosperm data adjusted for geographic variability in MAP, altitude, and latitude. Light blue squares show raw gymnosperm data before adjustment. Filled white circles and grey circles show mixed species (either angiosperm or unidentified) before and after adjustment for geographic variability, respectively

We hypothesise that the residual isotopic changes in adjusted cellulose and collagen records through time consist of two components: first, changing atmospheric chemistry, and second, changes in MAP, which are reasonably described by the regressions of Kohn1. Under this assumption we are able to constrain the pCO2 effect after correcting adjusted δ13Cp for the effect of changing MAP between <10 and >20 kyr, which we infer from an ensemble of coupled atmosphere-ocean general circulation models (GCMs, see Methods for further details). Note that these corrections are different from our adjustments for geographical variability; whilst the latter only adjust for geographical bias, the former correct for changes through time. We find that in most cases (~90% for fauna, ~95% for plants) the PMIP3-CMIP5 ensemble model predicts a change to wetter conditions during the Holocene. The average effect of MAP on the isotopic signal, constrained by GCMs, is therefore negative for both plants and fauna (Fig. 3b, c). The effect of faunal records, confined to Eurasia, is −0.4 ± 0.88‰, which is larger than both gymnosperms (−0.27 ± 0.55‰) and all plants (−0.13 ± 0.74‰) but smaller than plants from North America (−0.46 ± 0.88‰). Our corrections for changes in MAP imply a residual pCO2 effect during the deglacial rise in CO2 (~80.5 ppmv) of −0.53‰ for fauna, or equivalently −0.7 ± 1.9‰ per 100 ppmv (Fig. 3a). Only gymnosperm species are represented across our entire plant cellulose compilation, and these species distinguish a larger pCO2 effect of −1.7 ± 1.5‰ per 100 ppmv. Therefore, both collagen and cellulose records reflect changes in pCO2 (in addition to changing MAP), but with different magnitudes. Our fauna primarily reflect a dietary contribution from angiosperms, whereas our plant compilation is biased towards gymnosperm species at the LGM. We suggest that the disagreement between our plant and faunal records is likely caused by a genuine physiological difference in leaf gas-exchange strategy between angiosperm and gymnosperm plants31, 34.

Effect of atmospheric pCO2 on mean stable carbon isotope composition over the last deglaciation, determined from terrestrial records and from changes in MAP. a Magnitude of pCO2 effect predicted by models and palaeo-data. Error bars for models, fauna, and gymnosperms (all this study) and speleothems16 are 1σ propagated uncertainties, and 2 s.e. for fauna from Kohn15. b Changes in MAP predicted by PMIP3-CMIP5 multi-model ensemble between the LGM and mid-Holocene, used to constrain the pCO2 effect on our data set. c Geographical distribution of our data, showing the magnitude of MAP changes predicted by the multi-model ensemble over the same time period

The magnitudes of the pCO2 effect implied by our data are consistent with models of photosynthesis which predict a dynamic leaf gas-exchange strategy, and a variable ratio of intercellular to atmospheric pCO2 over the 180–400 ppmv range. This is less than that proposed by Breecker16 for speleothems, −1.6 ± 0.3‰ per 100 ppmv (1σ), but greater than that proposed by Kohn15 for fossil collagen, −0.03 ± 0.13‰ per 100 ppmv (2 s.e., see Fig. 3a). We suggest the latter discrepancy is due to the limited temporal resolution of that data set, which is neither large enough nor sufficiently well dated to resolve millennial-scale shifts in δ13Cp.

With respect to our gymnosperm cellulose record, we find that δ13C (adjusted for geographical variability) is best described by SJ-2012 and Voelker-2016g (SJ-2012; RMSE = 1.07, AIC = 25, BIC = 31; Voelker-2016g; RMSE = 1.04, AIC = 26, BIC = 34). This is not surprising because SJ-2012 is biased towards gymnosperm palaeo-data below ~350 ppmv. Our faunal analysis shows that the SJ-2012 model leads to an overestimation of the pCO2 effect for other plants and fauna, particularly at periods of low concentration. Therefore, although this model may be appropriate for gymnosperms, we suggest that SJ-2012 should not be used as a baseline to infer changes in angiosperm plants and hence the majority of ancient fauna. With respect to these records, the Voelker-2016a model best reproduces the magnitude of the deglacial shift observed in fauna (–0.53‰, Supplementary Table 4), but is offset from all cellulose records. The ~1.4‰ offset is probably related to our choice of a and b constants, and/or inaccuracies in the fitted relationship between ci/ca and ca. Another alternative is some hitherto unknown subtlety of the isotopic relationship between fauna and bulk diet. This last scenario is unlikely because the difference between the cellulose and collagen records, averaged over the Holocene, imply an average collagen-diet enrichment factor consistent with the value of 5.1‰ determined from modern controlled-feeding studies35,36,37, after factoring in the ~1‰ isotopic offset between cellulose and bulk leaf tissue (faunal diet)38. Further chamber and palaeo-data from angiosperm plants, across a wider range of pCO2, might be needed to shed light on the other explanations.

Discussion

Faunal δ13C studies have been used to interpret changes in forest cover across Western Europe during the last deglaciation. For example, isotopic analysis of late Pleistocene roe deer in northern France show a range from −19.0 to −20.9‰, and a shift to values more negative than −22.5‰ during the Holocene has been used to infer the presence of a ‘canopy effect’ on faunal δ13C during the deglaciation, considering only a correction for past changes in δ13\({\mathrm{C}}_{{\mathrm{CO}}_{\mathrm{2}}}\)39, if pCO2 effects are negligible. Although similar interpretations have been challenged28, 29, 40, presently the canopy effect and water availability are more frequently cited as the driving parameter behind δ13C trends of western European fauna during the late Pleistocene/Holocene transition30, 41.

Given the pCO2 effect displayed by our data, a cutoff of −22.5‰ would overestimate the extent of the canopy effect on faunal δ13C. Values more negative than −22.5‰ also reflect the postglacial rise in pCO2, via its effect on carbon isotope fractionation in C3 plants. The extent to which a genuine canopy effect is also reflected in our faunal record is difficult to determine. However, it is unlikely to be significant. First, there are no strong differences in δ13C across different species during the Holocene (species show similar means at approximately −21.7‰, when adjusted for geographical variability). The opposite result would be expected from a canopy effect, as only some of our species are forest-dwelling. Second, modern studies from temperate woodlands show limited effects on faunal δ13C, even when a canopy effect is present in vegetation42. However, the possibility of some small contribution from changing canopy cover is difficult to fully exclude, therefore our pCO2 effect for fauna is a maximum estimate. Considering the multiple lines of evidence, including plant chamber experiments and the fossil record, it is now more plausible to believe that shifts in terrestrial δ13C during the last deglaciation primarily reflect changes in pCO2, along with smaller contributions from changing MAP and possibly increased canopy cover. Our finding is supported by analysis of ancient and modern δ13C from wolves and bison bone collagen43 which show strong correlations between pCO2 and δ13C.

More generally, we propose that similarly rapid shifts in the carbon isotope baseline of C3 plants need to be considered throughout the Quaternary, particularly during periods of low pCO2, when atmospheric effects on photosynthetic fractionation are magnified. Faunal isotopes from predominantly C3 and mixed C3/C4 environments are routinely used to infer regional ecologies, under the assumption that δ13C mainly reflects growing season, mean annual temperature44 and MAP. We urge caution in this approach, since our analysis shows that shifts in terrestrial archives may simply reflect rapidly changing atmospheric chemistry, and not other environmental variables. Beyond the Quaternary, there is also evidence to suggest that other atmospheric variables may lead to significant changes in the carbon isotope baseline in deep time. Plant chamber experiments have revealed strong relationships between carbon isotope discrimination and changing pO234, 45, since Rubisco also as an affinity for oxygen. Whilst potentially relevant to geological periods of subambient or elevated pO2, the influence of oxygen on plant δ13C is probably minimal during the Quaternary because pO2 levels remained relatively stable over much of this period46. The short-term shifts we observe on millennial timescales are therefore more likely due to changes in pO2. In future, pCO2- and possibly O2-dependent models of carbon isotope fractionation should be used together with the regressions of Kohn1 to reconstruct changes in MAP or other atmospheric variables using ensembles of terrestrial archives. Rapid advancements in ice core measurements may help extend this approach further back in time, and offer more accurate tools for the reconstruction of ancient environments. Finally, there is now an intriguing body of evidence31, 34 which reveals strong phylogenetic differences in the carbon isotope response of plants to atmospheric extrema, but it is clear that several questions remain about the precise nature of these relationships. There is an urgent need for improved comprehensive models of photosynthetic fractionation, which are essential for pCO2 reconstruction beyond ice core records, as well as predicting uptake of future anthropogenic CO2 emissions by the terrestrial biosphere47.

Methods

Materials

Plant δ13C records were compiled from previously published studies of tree wood and Pinus needles, which were all pretreated to α-cellulose, with the exception of more recent wood samples48, 49, which were pretreated using standard acid–base–acid (ABA) protocols. Radiocarbon dates of collagen and plants were calibrated using OxCal v. 4.250 using the IntCal13 calibration curve51 whenever raw radiocarbon determinations were reported, and reported in kyr BP (where BP = 1950 CE). Faunal collagen δ13C was compiled from the Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator database as well as other previously published sources, are presented in Supplementary Data 1 (see also Supplementary Fig. 2). We selected herbivore cellulose from predominantly C3 environments (all >90%, most >99.5% according to ref. 52), excluding Reindeer (Rangifer tarandus) and other species known to consume large amounts of lichen. Over half our record comprises grazing and browsing ungulates (Supplementary Fig. 3), e.g. Cervus spp. (19%), Bos spp. (24%) and Equus spp. (17%).

Adjustments for geographic variability

Collagen and cellulose δ13C values were adjusted to MAP = 1000 mm, altitude = 840 m, latitude = 50 °N, using Eq. (1) of Kohn1, and the following procedure. First we obtained the altitude (m) for each location according to the GTOPO30 digital elevation model, available at https://lta.cr.usgs.gov/GTOPO30 (Accessed 13 Nov 2016). We also calculated modern annual precipitation for each location according to the WorldClim v. 1.4 model53, averaged over the period 1960-1990 AD53. We calculated adjusted values according to \(\delta ^{13}{\mathrm{C}}_{{\mathrm{adj}}} = \delta ^{13}{\mathrm{C}} + \delta {\prime}\), where \(\delta {\prime} = \delta _{{\mathrm{MAP}}} + \delta _{{\mathrm{alt}}} + \delta _{{\mathrm{lat}}}\). In turn, Eq. (1) of Kohn1 yields δMAP = −5.6 × log10(1000 + 300) − (−5.6 × log10(MAP + 300)), δalt = 0.00019 × (840 − altitude) and δlat = −0.0124 × 50 − (−0.0124 × |latitude|).

Calculation of pCO2 effect

We calculate the magnitude of the pCO2 effect across the LGM-Holocene transition according to the following assumption: \({\mathrm{\Delta }}\left( {\delta ^{13}{\bar{\mathrm C}}_{{\mathrm{adj}}}} \right) \approx {\mathrm{\Delta }}\left( {\delta ^{13}{\bar{\mathrm C}}_{{\mathrm{pCO}}_2}} \right)\) + \({\mathrm{\Delta }}\left( {\delta ^{13}{\bar{\mathrm C}}_{{\mathrm{MAP}}}} \right) + {\mathrm{\Delta }}\left( {\delta ^{13}{\bar{\mathrm C}}_{{\mathrm{CO}}_2}} \right)\). Here \({\mathrm{\Delta }}\left( {\delta ^{13}{\bar{\mathrm C}}_{{\mathrm{adj}}}} \right)\) is the total difference in mean faunal or plant δ13C adjusted for geographic variability in latitude, altitude and MAP, between >20 and <10 kyr. The latter values exclude the industrial era. Examination of the ice core records between >20 and <10 kyr shows that \({\mathrm{\Delta }}\left( {\delta ^{13}{\bar{\mathrm C}}_{{\mathrm{CO}}_2}} \right) \simeq 0.05\)‰, which is negligible, therefore: \({\mathrm{\Delta }}\left( {\delta ^{13}{\bar{\mathrm C}}_{{\mathrm{adj}}}} \right) \approx {\mathrm{\Delta }}\left( {\delta ^{13}{\bar{\mathrm C}}_{{\mathrm{pCO}}_2}} \right) + \Delta \left( {\delta ^{13}{\bar{\mathrm C}}_{{\mathrm{MAP}}}} \right)\). This expression assumes that the total difference in adjusted δ13C is approximately equal to the combined contributions of changing MAP, denoted as \({\mathrm{\Delta }}\left( {\delta ^{13}{\bar{\mathrm C}}_{{\mathrm{MAP}}}} \right)\), and changing pCO2, \({\mathrm{\Delta }}\left( {\delta ^{13}{\bar{\mathrm C}}_{{\mathrm{pCO}}_2}} \right)\). By rearranging this expression, and subtracting the contribution from changing MAP, we evaluated the magnitude of residual changes due to changing pCO2. \({\mathrm{\Delta }}\left( {\delta ^{13}{\bar{\mathrm C}}_{{\mathrm{MAP}}}} \right)\) was obtained using Δ(δ13CMAP) = −5.6 × log10(MAPLGM + 300) − (−5.6 × log10(MAPmid−H + 300)). To estimate regional changes in MAP, and associated uncertainties, we utilised seven coupled general circulation models (GCMs) of MAP at the LGM (21 kyr) and mid-Holocene (6 kyr). We obtained Palaeoclimate Modelling (PMIP3) and Coupled Modelling Intercomparison Project (CMIP5)54, 55 ensemble predictions of average yearly precipitation flux at each locality, available at https://pmip3.lsce.ipsl.fr (accessed June 2016). The change in MAP predicted by these models is shown in Supplementary Fig. 4, and the change in MAP predicted by the ensemble model is shown in Supplementary Fig. 5. These ensemble predictions were only available for the LGM and the mid-Holocene, so we corrected >20 kyr data using the LGM ensemble predictions, and <10 kyr data with the mid-Holocene predictions (Supplementary Fig. 6). We choose GCM ensemble predictions for two reasons: first, because they are largely independent of assumptions about stable carbon isotopes and water availability, which would create circularities in our approach, and second, because uncertainty estimates may be derived for MAP change. Additionally, studies have shown that using a multi-model ensemble mean is more accurate than choosing one particular model54, 56, 57. The seven GCMs are named in the Supplementary Information, and all model outputs are provided in Supplementary Data 1.

Models of photosynthetic fractionation

We computed four models as follows: model 1 (Farquhar-1982) was Eq. (1) with a constant ci/ca ratio chosen of 0.6. Although it is unlikely that plants employ a strategy of constant ci/ca under atmospheric extrema, this value was selected as a reasonable compromise for δ13Cp since it reproduced the modern globally averaged δ13Cp value from ref. 1 of −27.1‰. Model 2 (Voelker-2016g) was taken to be Eq. (1) modified by a linear dependence of ci/ca on ca for gymnosperms given by ref. 31 as ci/ca = 0.00038ca + 0.502. Model 3 (Voelker-2016a) was a similar model for woody angiosperms with ci/ca = 0.00031ca + 0.649. For all three of these models, we used a = 4.4‰ based on arguments of the diffusivity of atmospheric CO2, which is proportional to the square root of the reduced masses of the two isotopologues 13CO2 and 12CO258. For b, we used a value of 28.2‰, which also reasonably reproduces modern globally averaged δ13Cp using Voelker-2016g. It should be noted that Eq. (1) is a simplification of an expanded and refined equation given in ref. 4 that incorporates dissolution of CO2 in solution, and diffusion inside the leaf, as well as discriminations associated with dark respiration and photorespiration. Surprisingly little discussion has been made as to the possible influence of the effects of photorespiration and dark respiration in deep time, which should also exhibit a strong dependence on 1/ca (i.e. magnified at low ca). These components are intrinsically difficult to measure in modern plants. We assumed both effects were negligible. We think omission is justified, since these terms imply a shift in the carbon isotope composition of terrestrial C3 plants which is unreasonable in magnitude (~3–4‰), and in the wrong direction (i.e. a depletion in 13C at the LGM relative to Holocene data) to account for the deglacial rise in pCO2. Model 4 (SJ-2012) was the generalised hyperbolic model of Schubert and Jahren13, based on Eq. (2), with constants taken from fits performed in that paper, which are A = 28.26, B = 0.22, and C = 23.9. For the curves for SJ-2012 presented in Figs. 1 and 2, error bounds represented an expanded uncertainty in δ13C, which is the 1σ range of the data set of Kohn1 (1.62‰) combined in quadrature with 1σ propagated uncertainies from ice core splines. In other words, our error bounds considered both the range of the distribution of modern δ13C values, and analytical error in ice core measurements. They are therefore conservative estimates that represent the plausible range of δ13C values which may be expected in C3 plants according to that model. The magnitude of error bounds was similar for all other models, and for simplicity error bounds for other models were not drawn in our figures, and we choose to draw those only for SJ-2012.

We compared the four models with both our cellulose record and our faunal data, shifted to the equivalent plant values by subtracting \(\varepsilon _{{\mathrm{d}} - {\mathrm{c}}}^ \ast = 5.1\)‰. For model comparison we used three complimentary statistics: root mean square error (RMSE), Bayesian information criterion (BIC) and Akaike information criterion (AIC), all calculated from the residuals of each model fit to our records. The advantage of the latter two statistics is that they allow model selection based on a trade-off between goodness-of-fit and model complexity. Briefly, if predicted values of model M at time t are represented y t and data are represented by y i , we calculated RMSE as \(\sqrt {\left[ {\mathop {\sum}\nolimits_{t = 1}^n \left( {y_t - y_i} \right)^2} \right]{\mathrm{/}}n}\). BIC is calculated from \({\mathrm{ln}}(n)k - 2{\mathrm{ln}}({\cal L})\), where \({\cal L}\) is the maximised value of the likelihood for mdoel M, with number of free parameters k. AIC is calculated as \(2k - 2{\mathrm{ln}}({\cal L})\). All goodness-of-fit statistics are shown in Supplementary Tables 1–3.

Ice core compilation

CO2 concentrations were obtained from six Antarctic ice cores, EPICA Dome C (EDC)59,60,61,62,63,64, Talos Dome33, 65, EPICA Dronning Maud Land (EDML)33, 64,65,66,67, Siple68, 69, and records showing recent anthropogenic rise in CO2 concentration from the Law Dome and South Pole70. Pre-industrial records were synchronised on the AICC2012 timescale71. We obtained a Monte Carlo smoothing spline according to the procedure outlined in ref. 60. We performed 1000 replicate cubic spline fits to the entire data series, with input data picked randomly from the 1σ error range, and applied a 375 yr cutoff period to exclude high-frequency noise. Records for the anthropogenic era from the Law Dome and South Pole are presented on the age scale of ref. 70, cubic splined without a cutoff period, and then combined with the pre-industrial curve. The curve obtained for the corresponding pre-industrial δ13\({\mathrm{C}}_{{\mathrm{CO}}_{\mathrm{2}}}\) records was taken from ref. 33 and was obtained by a similar procedure, synchronised on the AICC2012 timescale, as well as incorporating records from the Law Dome and South Pole.

Data availability

Model output and all data used in the current study are made available in the figshare repository, 10.6084/m9.figshare.5497918. Additionally, radiocarbon dates may be queried using the OxCal database, where appropriate: https://c14.arch.ox.ac.uk/database/db.php?page=oxaResult.

References

Kohn, M. J. Carbon isotope compositions of terrestrial C3 plants as indicators of (paleo)ecology and (paleo)climate. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 19691–19695 (2010).

Lloyd, J. & Farquhar, G. D. 13C discrimination during CO2 assimilation by the terrestrial biosphere. Oecologia 99, 201–215 (1994).

Cernusak, L. A. et al. Environmental and physiological determinants of carbon isotope discrimination in terrestrial plants. New Phytol. 200, 950–965 (2013).

Brugnoli, E. & Farquhar, G. D. Photosynthesis, 399–434 (Springer, Dordrecht, 2000).

Diefendorf, A. F., Mueller, K. E., Wing, S. L., Koch, P. L. & Freeman, K. H. Global patterns in leaf 13C discrimination and implications for studies of past and future climate. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 5738–5743 (2010).

Krishnamurthy, R. & Epstein, S. Glacial-interglacial excursion in the concentration of atmospheric CO2: effect in the 13C/12C ratio in wood cellulose. Tellus B 42, 423–434 (1990).

Van de Water, P. K. & Leavitt, S. W. & Betancourt, J. Trends in stomatal density and 13C/12C ratios of Pinus flexilis needles during last glacial-interglacial cycle. Science 264, 239–243 (1994).

van der Plicht, J., Imamura, M. & Sakamoto, M. Dating of Late Pleistocene tree-ring series from Japan. Radiocarbon 54, 625–633 (2012).

Leavitt, S. & Danzer, S. Chronology from plant matter. Nature 352, 671 (1991).

Beerling, D. Predicting leaf gas exchange and δ13C responses to the past 30000 years of global environmental change. New Phytol. 128, 425–433 (1994).

Farquhar, G. D., O’Leary, M. H. & Berry, J. A. On the relationship between carbon isotope discrimination and the intercellular carbon dioxide concentration in leaves. Funct. Plant Biol. 9, 121–137 (1982).

Farquhar, G., Hubick, K., Condon, A. & Richards, R. in Stable Isotopes in Ecological Research (eds Rundel, P. W., Ehleringer, J. R. & Nagy, K. A.) 21–40 (Springer, New York, NY, 1989).

Schubert, B. A. & Jahren, A. H. The effect of atmospheric CO2 concentration on carbon isotope fractionation in C3 land plants. Geochim. Et. Cosmochim. Acta 96, 29–43 (2012).

Schubert, B. A. & Jahren, A. H. Global increase in plant carbon isotope fractionation following the last glacial maximum caused by increase in atmospheric pCO2. Geology 43, 435–438 (2015).

Kohn, M. Carbon isotope discrimination in C3 land plants is independent of natural variations in pCO2. Geophys. Perspect. Lett. 2, 35–43 (2016).

Breecker, D. O. Atmospheric pCO2 control on speleothem stable carbon isotope compositions. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 458, 58–68 (2017).

Bauska, T. K. et al. Carbon isotopes characterize rapid changes in atmospheric carbon dioxide during the last deglaciation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 3465–3470 (2016).

Ehleringer, J. R. & Cerling, T. E. Atmospheric CO2 and the ratio of intercellular to ambient CO2 concentrations in plants. Tree. Physiol. 15, 105–111 (1995).

Keenan, T. F. et al. Increase in forest water-use efficiency as atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations rise. Nature 499, 324 (2013).

Cerling, T. E., Ehleringer, J. R. & Harris, J. M. Carbon dioxide starvation, the development of C4 ecosystems, and mammalian evolution. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 353, 159–171 (1998).

Bender, M. M. Mass spectrometric studies of carbon 13 variations in corn and other grasses. Radiocarbon 10, 468–472 (1968).

Smith, B. N. & Epstein, S. Two categories of 13C/12C ratios for higher plants. Plant. Physiol. 47, 380–384 (1971).

Vogel, J. Isotopic evidence for the past climates and vegetation of southern Africa. Bothalia 14, 391–394 (1983).

Sponheimer, M. et al. Using carbon isotopes to track dietary change in modern, historical, and ancient primates. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 140, 661–670 (2009).

Cerling, T. E., Wang, Y. & Quade, J. Expansion of C4 ecosystems as an indicator of global ecological change in the late Miocene. Nature 361, 344–345 (1993).

Cerling, T. E. et al. Global vegetation change through the Miocene/Pliocene boundary. Nature 389, 153–158 (1997).

Hoppe, K. A., Paytan, A. & Chamberlain, P. Reconstructing grassland vegetation and paleotemperatures using carbon isotope ratios of bison tooth enamel. Geology 34, 649–652 (2006).

Richards, M. & Hedges, R. Variations in bone collagen δ13C and δ15N values of fauna from Northwest Europe over the last 40 000 years. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 193, 261–267 (2003).

Stevens, R. E. & Hedges, R. E. Carbon and nitrogen stable isotope analysis of northwest European horse bone and tooth collagen, 40,000 BP-present: palaeoclimatic interpretations. Quat. Sci. Rev. 23, 977–991 (2004).

Drucker, D. G., Bridault, A., Hobson, K. A., Szuma, E. & Bocherens, H. Can carbon-13 in large herbivores reflect the canopy effect in temperate and boreal ecosystems? Evidence from modern and ancient ungulates. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 266, 69–82 (2008).

Voelker, S. L. et al. A dynamic leaf gas-exchange strategy is conserved in woody plants under changing ambient CO2: evidence from carbon isotope discrimination in paleo and CO2 enrichment studies. Glob. Change Biol. 22, 889–902 (2016).

Diefendorf, A. F., Freeman, K. H., Wing, S. L., Currano, E. D. & Mueller, K. E. Paleogene plants fractionated carbon isotopes similar to modern plants. Earth. Planet. Sci. Lett. 429, 33–44 (2015).

Eggleston, S., Schmitt, J., Bereiter, B., Schneider, R. & Fischer, H. Evolution of the stable carbon isotope composition of atmospheric CO2 over the last glacial cycle. Paleoceanography 31, 434–452 (2016).

Porter, A. S., Yiotis, C., Montañez, I. P. & McElwain, J. C. Evolutionary differences in δ13C detected between spore and seed bearing plants following exposure to a range of atmospheric O2:CO2 ratios; implications for paleoatmosphere reconstruction. Geochim. et Cosmochim. Acta 213, 517–533 (2017).

Vogel, J. C. Isotopic assessment of the dietary habits of ungulates. S. Afr. J. Sci. 74, 298–301 (1978).

Van der Merwe, N. J. in The Chemistry of Prehistoric Human Bone (ed. Price, T. D.) 105–125 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1989).

Ambrose, S. H. in Investigations of Ancient Human Tissue: Chemical Analyses in Anthropology. Food and Nutrition in History and Anthropology Vol. 10 (ed. Sandford, M. K.) 59–130 (Gordon and Breach, Langhorne, PA, 1993).

Leavitt, S. W. & Long, A. Evidence for 13C/12C fractionation between tree leaves and wood. Nature 298, 742–744 (1982).

Drucker, D., Bocherens, H., Bridault, A. & Billiou, D. Carbon and nitrogen isotopic composition of red deer (Cervus elaphus) collagen as a tool for tracking palaeoenvironmental change during the Late-Glacial and Early Holocene in the northern Jura (France). Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 195, 375–388 (2003).

Hedges, R. E., Stevens, R. E. & Richards, M. P. Bone as a stable isotope archive for local climatic information. Quat. Sci. Rev. 23, 959–965 (2004).

Stevens, R. E., Hermoso-Buxán, X. L., Marn-Arroyo, A. B., González-Morales, M. R. & Straus, L. G. Investigation of Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene palaeoenvironmental change at El Mirón cave (Cantabria, Spain): insights from carbon and nitrogen isotope analyses of red deer. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 414, 46–60 (2014).

Bonafini, M., Pellegrini, M., Ditchfield, P. & Pollard, A. Investigation of the ‘canopy effect’in the isotope ecology of temperate woodlands. J. Archaeol. Sci. 40, 3926–3935 (2013).

Bump, J. K. et al. Stable isotopes, ecological integration and environmental change: wolves record atmospheric carbon isotope trend better than tree rings. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 274, 2471–2480 (2007).

Cotton, J. M., Cerling, T. E., Hoppe, K. A., Mosier, T. M. & Still, C. J. Climate, CO2, and the history of North American grasses since the Last Glacial Maximum. Sci. Adv. 2, e1501346 (2016).

Beerling, D. et al. Carbon isotope evidence implying high O2/CO2 ratios in the Permo-Carboniferous atmosphere. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 66, 3757–3767 (2002).

Stolper, D., Bender, M., Dreyfus, G., Yan, Y. & Higgins, J. A Pleistocene ice core record of atmospheric O2 concentrations. Science 353, 1427–1430 (2016).

Keeling, R. F. et al. Atmospheric evidence for a global secular increase in carbon isotopic discrimination of land photosynthesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 10361–10366 (2017).

Pearson, C. L. et al. Potential for a new multimillennial tree-ring chronology from subfossil Balkan river oaks. Radiocarbon 56, S51–S59 (2014).

Vogel, J. & Van der Plicht, J. Calibration curve for short-lived samples, 1900–3900 BC. Radiocarbon 35, 87–91 (1993).

Ramsey, C. B. et al. Bayesian analysis of radiocarbon dates. Radiocarbon 51, 337–360 (2009).

Reimer, P. J. et al. IntCal13 and Marine13 radiocarbon age calibration curves 0–50,000 years cal BP. Radiocarbon 55, 1869–1887 (2013).

Still, C. J., Berry, J. A., Collatz, G. J. & DeFries, R. S. Global distribution of C3 and C4 vegetation: carbon cycle implications. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 17, 1006 (2003).

Hijmans, R. J., Cameron, S. E., Parra, J. L., Jones, P. G. & Jarvis, A. Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 25, 1965–1978 (2005).

Braconnot, P. et al. Evaluation of climate models using palaeoclimatic data. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 417 (2012).

Taylor, K. E., Stouffer, R. J. & Meehl, G. A. An overview of CMIP5 and the experiment design. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 93, 485–498 (2012).

Sillmann, J., Kharin, V., Zhang, X., Zwiers, F. & Bronaugh, D. Climate extremes indices in the CMIP5 multimodel ensemble: Part 1. Model evaluation in the present climate. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmospheres 118, 1716–1733 (2013).

Stroeve, J. C. et al. Trends in Arctic sea ice extent from CMIP5, CMIP3 and observations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L16502 (2012).

Craig, H. Carbon 13 in plants and the relationships between carbon 13 and carbon 14 variations in nature. J. Geol. 62, 115–149 (1954).

Schneider, R., Schmitt, J., Köhler, P., Joos, F. & Fischer, H. A reconstruction of atmospheric carbon dioxide and its stable carbon isotopic composition from the penultimate glacial maximum to the last glacial inception. Climate 9, 2507–2523 (2013).

Schmitt, J. et al. Carbon isotope constraints on the deglacial CO2 rise from ice cores. Science 336, 711–714 (2012).

Lourantou, A., Chappellaz, J., Barnola, J.-M., Masson-Delmotte, V. & Raynaud, D. Changes in atmospheric CO2 and its carbon isotopic ratio during the penultimate deglaciation. Quat. Sci. Rev. 29, 1983–1992 (2010).

Lourantou, A. et al. Constraint of the CO2 rise by new atmospheric carbon isotopic measurements during the last deglaciation. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 24, GB003545 (2010).

Monnin, E. et al. Atmospheric CO2 concentrations over the last glacial termination. Science 291, 112–114 (2001).

Monnin, E. et al. Evidence for substantial accumulation rate variability in Antarctica during the Holocene, through synchronization of CO2 in the Taylor Dome, Dome C and DML ice cores. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 224, 45–54 (2004).

Bereiter, B. et al. Mode change of millennial CO2 variability during the last glacial cycle associated with a bipolar marine carbon seesaw. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 9755–9760 (2012).

Lüthi, D. et al. CO2 and O2/N2 variations in and just below the bubble-clathrate transformation zone of Antarctic ice cores. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 297, 226–233 (2010).

Siegenthaler, U. et al. Supporting evidence from the EPICA Dronning Maud Land ice core for atmospheric CO2 changes during the past millennium. Tellus B 57, 51–57 (2005).

Ahn, J. & Brook, E. J. Siple dome ice reveals two modes of millennial CO2 change during the last ice age. Nat. Commun. 5, 3723 (2014).

Ahn, J., Brook, E. J. & Buizert, C. Response of atmospheric CO2 to the abrupt cooling event 8200 years ago. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 604–609 (2014).

Rubino, M. et al. A revised 1000 year atmospheric δ13C-CO2 record from Law Dome and South Pole, Antarctica. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmospheres 118, 8482–8499 (2013).

Veres, D. et al. The Antarctic ice core chronology (AICC2012): an optimized multi-parameter and multi-site dating approach for the last 120 thousand years. Climate 9, 1733–1748 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We thank Sarah Eggleston, Ben Hmiel, Lee Murray, and Vinesh Rajpaul for their advice, and Patrick Roberts for his suggestions and critical reading. The manuscript was much improved by the constructive comments of the anonymous reviewers. V.J.H. and E.L. received support from the Clarendon Fund, University of Oxford. We acknowledge support from the UK Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) for the Oxford node of the national NERC Radiocarbon facility. Open access fees were kindly provided by Oxford University’s RCUK Open Access Block Grant. We also acknowledge the World Climate Research Programme’s Working Group on Coupled Modelling, which is responsible for CMIP, and we thank the climate modelling groups for producing and making available their model output.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.J.H. designed research, E.L., A.J. and C.B.R. assisted research. V.H. analysed the data and wrote the paper with input from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hare, V.J., Loftus, E., Jeffrey, A. et al. Atmospheric CO2 effect on stable carbon isotope composition of terrestrial fossil archives. Nat Commun 9, 252 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-02691-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-02691-x

This article is cited by

-

Cryptographic triboelectric random number generator with gentle breezes of an entropy source

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Soil depth gradients of organic carbon-13 – A review on drivers and processes

Plant and Soil (2024)

-

Tooth enamel nitrogen isotope composition records trophic position: a tool for reconstructing food webs

Communications Biology (2023)

-

A study on benthic molluscs and stable isotopes from Kutch, western India reveals early Eocene hyperthermals and pronounced transgression during ETM2 and H2 events

Swiss Journal of Palaeontology (2022)

-

Ancient Great Wall building materials reveal environmental changes associated with oases in northwestern China

Scientific Reports (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.