Abstract

The active control of a molecular spin represents one of the main challenges in molecular spintronics. Up to now spin manipulation has been achieved through the modification of the molecular structure either by chemical doping or by external stimuli. However, the spin of a molecule adsorbed on a surface depends primarily on the interaction between its localized orbitals and the electronic states of the substrate. Here we change the effective spin of a single molecule by modifying the molecule/metal interface in a controlled way using a low-temperature scanning tunneling microscope. A nickelocene molecule reversibly switches from a spin 1 to 1/2 when varying the electrode–electrode distance from tunnel to contact regime. This switching is experimentally evidenced by inelastic and elastic spin-flip mechanisms observed in reproducible conductance measurements and understood using first principle calculations. Our work demonstrates the active control over the spin state of single molecule devices through interface manipulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The ability to modify the spin of a molecule in a controlled and reversible way is essential to develop novel spin-based technologies1. Although the spin of surface-supported single molecules is mainly determined by molecule/surface interactions2,3,4,5, it can be modified by external parameters such as the mechanical6 or the chemical modification of the molecule7,8,9,10,11,12, the application of electric fields13,14,15, light or temperature16,17. The effect of approaching the metallic tip of a scanning tunneling microscope (STM) to the molecule is a way to alter the local environment of the molecule18,19. It can result in structural relaxations20, or even modify the molecular configuration through the application of bias pulses21, ultimately changing the spin state of the molecule. However, determining the factors leading the spin modification of a molecule when adsorbed on a surface or when coupled between metallic electrodes is a complex process in which different subtle contributions need to be considered.

Scanning tunneling spectroscopy (STS) is a useful tool to determine the spin of surface-supported magnetic single objects by exploring the zero-bias anomalies produced by different spin-flip scattering mechanisms22,23. While the Kondo screening involves the elastic spin-flip scattering of conduction electrons with the magnetic impurity below a critical temperature T K 24, the magnetic anisotropy of single objects leads to an inelastic scattering of these electrons. In fact, the magnetic anisotropy of surface-supported objects—atoms or molecules—has been attracting a growing interest in relation to ultra-dense storage technology25 and quantum computing26. From a practical viewpoint, a uniaxial magnetic anisotropy energy of the form \(DS_z^2\) provides stable magnetic states into which information can be encoded and may, moreover, be externally controlled11,21,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34. The general picture to address is that single objects have the potential for both magnetic anisotropy and the Kondo effect35, the outcome of their interplay depending on the object’s spin23,36,37,38 and on the relative weight of k B T K vs. D 39,40.

Elastic and inelastic tunneling spectra can be used to probe the above mentioned interplay in an environment that can be characterized with atomic-scale precision. In recent experiments11,12,31,32,33, different surface topologies were used to tune the Kondo exchange interaction between the spin and the underlying metal, while spin control was possible through hydrogen doping of transition metal atoms.

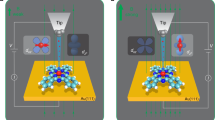

Here, we control the spin of a single-metallocene molecule in a junction using a STM. We attach a S = 1 molecule with an easy-plane magnetic anisotropy (D > 0), nickelocene (Ni(C5H5)2, noted Nc hereafter), to the tip apex of a STM and form an atomically precise contact with a Cu(100) surface. The molecular spin switches from 1 to \(1/2\) when we go from the tunnel to the contact transport regime, as monitored by the two-order of magnitude change in the differential conductance near the Fermi level. This abrupt difference comes from the different nature of the spin–flip scattering that governs the conductance around the Fermi energy of the junction in the two regimes. Our findings are corroborated by density functional theory (DFT) calculations.

Results

Tunnel regime

An image of the Cu(100) surface after a molecular deposition is shown in Fig. 1a, in which isolated Nc decorate the surface terraces. The molecules show a ring-shaped pattern, indicating that one cyclopentadienyl ring (C5H5, noted Cp hereafter) is exposed to vacuum, i.e., the long molecular axis of Nc is perpendicular to the Cu(100) surface41.

Nickelocene adsorption on Cu(100) and on the tip apex. a STM image acquired with a metallic tip (5.6 × 5.6 nm2, −15 mV, 20 pA). b Counter image of the Cu atom obtained with a Nc-terminated tip (1.7 × 1.3 nm2, −15 mV, 20 pA). c Calculated relaxed configuration of a Nc molecule on top of a Cu adatom on Cu(100), together with the simulated STM image. Atom colors: Cu (yellow), C (gray), H (white) and Ni (green). d dI/dV spectra and their derivative acquired with a Cu-tip over a Nc molecule (solid blue line) and with a Nc-terminated tip over the Cu(100) surface (solid red line). Feedback loop opened at 100 pA and −15 mV

We found that in order to contact nickelocene between both electrodes, surface and tip, it is more stable to first transfer the molecule from the metallic surface to the tip, by approaching the tip to the target molecule at −1 mV and 50 pA34. Prior to the molecular transfer, care was taken to select a monoatomically sharp tip apex42. Information may be gathered on the status of the Nc at the tip apex by acquiring counter-images43, which consist in imaging single atoms on the surface with the molecular tip. The typical molecular pattern observed in the counter images of Cu adatoms is presented in Fig. 1b and differs from the featureless protrusion observed with a metallic tip (encircled in Fig. 1a). The pattern reveals that the tip is terminated by a Cp ring of a tilted Nc molecule, the tilt angle exhibiting some tip dependency. To confirm this assignment we mimicked the molecular tip through DFT calculations by considering a Nc molecule adsorbed on a Cu atom on Cu(100) (inset of Fig. 1c, see Methods). The molecule is undeformed, tilted by 13° with respect to the surface normal and linked through two C atoms to the Cu atom. The corresponding simulated image in Fig. 1c is in good agreement with the experimental counter-image of Fig. 1b. Note that in a previous work34 in order to determine the magnetic anisotropy of a Nc on top of a Cu atom, the molecule was forced to be centered with respect to the Cu adatom underneath. However, the current results show that the relaxed situation is the one in which the molecule is tilted.

The top panel of Fig. 1d presents the dI/dV spectrum acquired with a Nc-tip above Cu(100). For comparison, we have included the dI/dV spectrum acquired with a metallic tip above a Nc molecule on Cu(100). Both spectra were acquired with a lock-in amplifier using a frequency of 716 Hz and an amplitude of 150 μV rms; the metallic tip was verified to have a flat electronic structure in the bias range presented. The steps, symmetric with respect to zero bias, that are visible in the dI/dV correspond to the manifestation of efficient spin–flip excitations within the molecule34. These occur between the ground state \(\left| {S = 1,M = 0} \right\rangle\) and the doubly degenerate \(\left| {S = 1,M = \pm 1} \right\rangle\) excited states of the molecule, the threshold energy observed corresponding to the longitudinal magnetic anisotropy energy, D. The bottom panel shows the numerical derivative of the dI/dV spectra in order to facilitate the identification of the threshold values. For Nc on the surface we find D = (3.2 ± 0.1) meV, while for Nc on the tip the magnetic anisotropy grows to D = (3.7 ± 0.3) meV. This reflects changes in the local ligand field induced by the different adsorption configuration21,30,34.

Contact regime

We then engineer a molecular junction by bringing the Nc-tip into contact with Cu(100). For an increased control over the molecular junction, the contact is always performed atop a copper surface atom thanks to the use of atomically-resolved images (Inset of Fig. 2b). These images are routinely acquired by scanning the molecular tip while in contact with the surface44,45, which can be taken as an indication of the robustness of a Nc-tip to external strain. The right panel of Fig. 2a presents the conductance (G) vs. tip displacement (z) curve acquired at a fixed bias of −2 mV with a Nc-tip vertically displaced towards the surface. For the G(z) measured at −2 mV, an abrupt increase of G by more than a factor 10 (G = 0.7) reveals the transition, indicated by a dashed line, between the tunneling and the contact regime (see Supplementary Fig. 1). As we show below, the sudden change in G is exclusively driven by a spin switch of nickelocene. Note that here the tip is moved from its initial tunneling position z = −2.1 Å (G = 2 × 10−4 in units 2e 2 h −1) up to the contact point z = 0 (G = 0.04). Once the contact is established, if we reverse the process and increase the tip–sample distance, we do not find the contact point exactly at the same z. Typical variations of the contact point are around 10–20 pm, indicating some hysteresis effects. Notice also that the exact values of the conductance as well as of the contact position under the same conditions present some tip dependency.

Spectroscopy of the molecular junction. a Left panel: 2D intensity plot of dI/dV spectra acquired with a Nc-tip at increasing z. The intensity of the spectra has been normalized by the opening conductance value (at −30 mV) of the spectrum at z = 0 Å. As a guideline to identify the differences, three characteristic spectra (white dashed lines) are superimposed. Right panel: G-vs.−z curve measured at −2 mV for a Nc-tip approaching the Cu(100) surface. The boundary between the tunnel and the contact regime occurs at z = 0 pm and is indicated with a dashed line. b Individual dI/dV spectra in the tunnel (bottom panel) and contact (top panel) regimes for several z. Note that right after contact, the width of the Kondo resonance is smaller than the inelastic excitation threshold. Inset: Contact image of the Cu(100) surface using a Nc-terminated tip (2 × 1.4 nm2; 300 pA, 30 mV). The cross indicates the contact point. c Evolution of T K with z. The Kondo temperature is 4.5 K or lower at z = 0, and 32.7 K at z = 0.8 Å. d Evolution of the resonance maximum σ with T/T K, where T = 2.4 K is the working temperature. σ and T K are extracted from the Frota fits (see Supplementary Fig. 2)

To elucidate this finding, we present in the left panel of Fig. 2a a two-dimensional intensity plot of a series of dI/dV spectra acquired at varying z. For completeness, Fig. 2b presents the spectra for decreasing tip–surface distances. The spectra reveal the presence of spin-flip scattering events, whose nature may be reversibly controlled via z. Within the tunneling regime, the spectra exhibit inelastic spin-flip excitations as anticipated in Fig. 1d. We note an enhancement of the differential conductance at voltages corresponding to the excitation threshold, which is increasingly pronounced as the contact point is approached (z > −0.5 Å). Recent studies have pointed out that this enhancement could reflect many-body effects including Kondo-like phenomena23,37,38. However, this scenario also requires a sizable reduction of the magnetic anisotropy energy, and therefore of the excitation threshold11,31, at variance with our experimental observations. The enhancement here rather reflects a stationary population of excited states23,46,47,48 due to the increasingly large currents flowing through the junction when approaching contact. This so-called spin pumping can be expected to be significant due to the efficiency of the spin-flip excitations in Nc produced by tunneling electrons34, or more generally, in molecules49,50,51.

The most striking result is found once the molecular contact to the surface is established (z > 0). As we anticipated above, a sudden increase in the conductance occurs at zero bias (Fig. 2a), which we ascribe to the presence of a Kondo resonance. As shown in Fig. 2a, a sharp peak appears in the dI/dV, while the inelastic excitation thresholds are lost. The emergence of a spin-1 Kondo effect in the presence or in the absence of positive magnetic anisotropy is in principle possible39,40—the former case being unlikely here as the resonance does not split apart29. However, we find that the system actually behaves as a spin 1/2-system. The peak is perfectly fitted by a Frota function (see Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 1), which is close to the exact line shape expected for a spin-1/2 Kondo system52. From the fit, we find that the peak is centered at \(\epsilon _{\mathrm{K}}\) = (0.0 ± 0.1) meV for all used tips up to the highest tip excursion explored (0.8 Å). The line width, therefore T K, increases nearly exponentially with z (Fig. 2c), similarly to other junctions comprising a single Kondo impurity53,54,55. Even though one would expect a linear increase of the d-level broadening with z considering the behavior of the Kondo temperature, here we have seen that the molecular levels follow a complex behavior due to the involved interaction with the tip (see Supplementary Fig. 3). To further confirm the spin-1/2 nature of the Kondo effect, we recall that the resonance amplitude (noted σ) should be a universal function of the normalized temperature T/T K. For a quantitative analysis we therefore fit the curve in Fig. 2d to the function σ = [1 + (T/T K)2(21/s − 1)]−s (in units of 2e 2 h −1)56 and extract s = (0.29 ± 0.02), in remarkable agreement with the spin-1/2 Kondo effect of semiconductor quantum dots57. The amplitude of the resonance is close to the unitary limit and indicates a complete Kondo screening. Note that in a previous work55 non-equilibrium effects were shown to be absent in the Kondo resonance even at contact. Our findings therefore strongly support the emergence of a spin-1/2 Kondo effect where there is no magnetic anisotropy. To elucidate its origin, here below, we show through DFT calculations that Nc switches its spin from 1 to 1/2 upon contact with the surface.

Density functional theory calculations

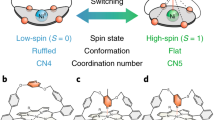

The DFT calculations were performed by modeling the molecular tip by a Nc atop a Cu atom adsorbed on a Cu(100) plane (Fig. 3a). The molecular tip was placed at different distances from a Cu(100) surface and the junction was fully relaxed. Figure 3c–e shows the resulting molecular junctions for the three most representative configurations (see frontal views in Supplementary Fig. 4). In Fig. 3c, the distance between the two Cu atomic planes (noted d) is 12.17 Å and corresponds to the tunneling regime (see Fig. 1c) described previously. Figure 3d shows the molecular junction at d = 11.14 Å and corresponds to the transition between the tunneling and contact regimes. The transition point has been assigned to the point in which a change in the behavior of structural parameters is observed, and has been confirmed by the theoretical transmission probabilities (Fig. 3f). The molecule is distorted at the transition, but still bonded to the Cu atom through two C atoms. Finally, Fig. 3e corresponds to d = 9.66 Å and is representative of the molecular junction in the contact regime. The molecule exhibits Cp rings that are parallel to both metallic planes and the Cu atom is coordinated to five C atoms. Figure 3b quantifies the structural changes with d. As shown, at the transition point the distances between the Cu and Ni atom with respect to the tip electrode, noted d 1 and d 1 + d 2 respectively, are maximum, as well as the tilt difference between the Cp rings, noted ΔΘ. The distance between the Ni atom and the surface-electrode (noted d 3) instead decreases continuously with d. Experimentally, we have seen that in the tunneling regime, despite the slightly different initial orientations that the molecule might have on the tip, similar results are obtained in the dI/dV spectra for different molecular tips when going to contact. This indicates that the Nc molecule tends to adopt always the same configuration, with parallel Cp rings, when contacted between the tip and the surface. From Fig. 3f we can obtain the ratio between the total transmission probabilities for the different spin channels (spin-up T ↑, spin-down T ↓) and find a −74% spin polarization in the tunneling regime and −55% in contact, where the spin polarization is \(\frac{{T_ \uparrow - T_ \downarrow }}{{T_ \downarrow + T_ \uparrow }}\). The decreased value at contact is in agreement with the trend found in a previous theoretical study58.

Structural and magnetization analysis of the molecular junction. a Structure of the calculated molecular junction, including the main relevant distance parameters. b The panels show how the structural parameters d 1, d 2, d 3, ΔΘ change as a function of d. The structure of the molecular junction for: c the tunneling regime (d = 12.17 Å), d the transition between the tunneling and the contact regimes (d = 11.14 Å), and e the contact regime (d= 9.66 Å). f Total transmission (black line) and the transmission per spin channel (red and blue lines) at the Fermi level for the explored configurations. g Magnetization of: Nc (black), Ni (red), Cu atom (green) as a function of d. Full symbols correspond to SIESTA (Mulliken) results and open symbols to VASP (Bader) results

Figure 3g presents how the magnetization of the Nc molecule, the Ni atom and the Cu atom change with d. In the tunneling regime, the calculated magnetic moment for Nc is 1.7 μ B, the Ni atom carrying 1 μ B. At the transition, these values decrease to 1 and 0.7 μ B respectively, and afterwards, at contact, stabilize around 0.75 μ B for Nc and 0.5 μ B for the Ni atom. The Cu atom remains non-magnetic during the contact process. The initial magnetic moment of the molecule is halved when contacted between the two electrodes, meaning that the molecular spin changes from S = 1 to S = 1/2. Such a spin switch is in agreement with the spectroscopic fingerprints highlighted experimentally.

The change on the molecular charge with respect to the gas phase from tunneling (−0.12e −) to contact (+0.07e −) is not enough to explain such a change on the magnetization. To scrutinize the effect of the deformation of the molecule on the molecular magnetization, the magnetization of the isolated Nc molecule was computed using the geometrical configurations found previously in the molecular junction when changing z (Fig. 3c–e). No relevant difference was observed for the different configurations, indicating that the magnetization change is neither driven by the molecule-substrate charge transfer nor by the deformation suffered by the molecule.

Figure 4a presents the spin-resolved transmission for the tunnel (thick line) and contact (thin line) regimes. The transmission of Fig. 4a implies that the transport is mainly due to the hybridization of surface electronic states with the frontier molecular orbitals, which are d xz —and d yz —based molecular orbitals (see Supplementary Fig. 5)34. To get a deeper understanding of the different features observed in the transmission function, the density of states projected (PDOS) onto the C(2p) and Ni(3d) atomic orbitals are shown in Fig. 4b. The clear correspondence between spin up and spin down peaks on the transmission function and the PDOS (Fig. 4b) makes it possible to assign both peaks to the transmission through the spin-polarized degenerate frontier orbitals. The comparison between contact and tunnel results shows that the peaks associated to the frontier-orbital in both spin up and spin down channels shift towards the Fermi level in the contact regime, reducing the exchange splitting energy due to the screening of the intra-orbital Coulomb repulsion (U). This is due to the enhancement of the molecule–electrode interaction that also induces a more pronounced broadening of the molecular levels. Such increase of the hybridization (Γ) reduces the charge in the majority spin and increases the minority spin occupation. Our analysis then shows that both effects, namely, the increase of Γ and the reduction of U contribute to halve the magnetic moment of the molecule in the contact regime. Therefore, the spin transition can be explained by the coupling to the substrate of the frontier orbitals located close to the Fermi level.

Transmission and PDOS of the molecular junction. a Spin-resolved electron transmission as a function of electron energy with respect to the Fermi energy for the Nc-tip above Cu(100). The thick line corresponds to the tunneling configuration (Fig. 3c) and the thin line to the contact configuration (Fig. 3d). b Density of states projected (PDOS) onto the C(2p) and Ni(3d) atomic orbitals for the tunneling (thick line) and for the contact (thin line) regimes. A comparison between SIESTA and VASP results can be found in Supplementary Fig. 6

Discussion

In summary, we have shown how the spin of a Nc molecule and, associated, spin-flip scattering from Nc can be reversibly modified via a controlled contact to a copper electrode. The spin transition takes place due to the enhanced electronic screening following the Nc-surface contact. On a more general note, the portability of the Nc molecule or eventually of other metallocenes59 via the STM tip offers novel opportunities for testing how surface-supported objects modify the molecular magnetism of these molecules.

Methods

STM measurements

The experiments were performed in an ultra-high vacuum STM operated at 2.5 K. A clean Cu(100) surface was prepared by repeated cycles of Ar+ sputtering and annealing up to 800 K at a base pressure of 2 × 10−10 mbar. Nickelocene molecules were deposited from a crucible onto the cold copper surface (below 80 K) at a rate of 0.025 ML/min resulting in a sub-monolayer coverage. Directly after molecular deposition, the sample was inserted in the STM. Analysis of STM data were performed with the WSxM software60.

Calculation details

Calculations were carried out using two DFT packages. VASP61,62,63,64,65,66 has been used to explore the adsorption of the Nc molecule on a STM tip modeled by a Cu(100) surface with a Cu adatom acting as a monoatomic tip apex. Geometrical effects when a second electrode (a Cu(100) surface) was approached have been evaluated also with VASP (see Fig. 3a). SIESTA67 calculations confirmed VASP results about the electronic and magnetic properties of the Nc-terminated tip/Cu(100) interface and allowed us to perform electronic transport calculations using TRANSIESTA68.

We optimized the structure of the Nc-terminated tip/Cu(100) interface using DFT at the spin-polarized generalized gradient approximation (GGA-PBE) level, as implemented in VASP61,62,63,64,65,66. In order to introduce long-range dispersion corrections, we employed the so-called DFT-D2 approach proposed by Grimme69. We used a plane wave basis set and the projected augmented wave (PAW) method with an energy cutoff of 400 eV. The two surfaces representing substrate and tip were modeled using a slab geometry with a 4 × 4 surface unit cell and 6 layers for the surface holding the tip–apex and the molecule, and 7 layers for the approaching surface electrode.

The valence–electron wavefunctions were expanded in a basis set of local orbitals in SIESTA. A double-ζ plus polarization (DZP) basis set was used to describe the Nc molecule and surface-atom electrons. Diffuse orbitals were used to improve the surface electronic description and a single-ζ plus polarization basis set for the copper electrodes. The use of a DZP basis set to describe the adsorbate states is mandatory in order to yield correct transmission functions70. The k-point sampling was converged at 3 × 3, although the sampling was 11 × 11 for the transmission calculations. These transport calculations were carried out from first-principles with a method based on non-equilibrium Green’s functions combined with DFT as implemented in the TranSIESTA package68. The Ni pseudopotential used in the SIESTA calculations was extracted from reference71.

Data availability

The authors declare that relevant data supporting the findings of this study are available on request.

References

Cinchetti, M., Dediu, V. A. & Hueso, L. E. Activating the molecular spinterface. Nat. Mater. 16, 507–515 (2017).

Brede, J. et al. Spin and energy-dependent tunneling through a single molecule with intramolecular spatial resolution. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 047204 (2010).

Wende, H. et al. Substrate-induced magnetic ordering and switching of iron porphyrin molecules. Nat. Mater. 6, 516–520 (2007).

Bernien, M. et al. Tailoring the nature of magnetic coupling of fe-porphyrin molecules to ferromagnetic substrates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 047202 (2009).

Lodi Rizzini, A. et al. Coupling of single, double, and triple-decker metal-phthalocyanine complexes to ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic substrates. Surf. Sci. 630, 361–374 (2014).

Frisenda, R. et al. Stretching-induced conductance increase in a spin-crossover molecule. Nano. Lett. 16, 4733–4737 (2016).

Bartolomé, J. et al. Reversible fe magnetic moment switching in catalytic oxygen reduction reaction of fe-phthalocyanine adsorbed on Ag(110). J. Phys. Chem. C 119, 12488–12495 (2015).

Miguel, J., Hermanns, C. F., Bernien, M., Krüger, A. & Kuch, W. Reversible manipulation of the magnetic coupling of single molecular spins in fe-porphyrins to a ferromagnetic substrate. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2, 1455–1459 (2011).

Wäckerlin, C. et al. Controlling spins in adsorbed molecules by a chemical switch. Nat. Commun. 1, 61 (2010).

Mugarza, A. et al. Spin coupling and relaxation inside molecule-metal contacts. Nat. Commun. 2, 490 (2011).

Jacobson, P. et al. Quantum engineering of spin and anisotropy in magnetic molecular junctions. Nat. Commun. 6, 8536 (2015).

Jacobson, P. et al. Potential energy–driven spin manipulation via a controllable hydrogen ligand. Sci. Adv. 3, e1602060 (2017).

Zhang, Y. & Deng, M. Electrical control of spin states of ferrocene on cu(111). J. Phys. Chem. C 119, 21681–21687 (2015).

Harzmann, G. D., Frisenda, R., van der Zant, H. S. J. & Mayor, M. Single-molecule spin switch based on voltage-triggered distortion of the coordination sphere. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 13425–13430 (2015).

Meded, V. et al. Electrical control over the fe(ii) spin crossover in a single molecule: theory and experiment. Phys. Rev. B 83, 245415 (2011).

Rösner, B. et al. Reversible photoswitching of a spin-crossover molecular complex in the solid state at room temperature. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 12976–12980 (2015).

Warner, B. et al. Temperature- and light-induced spin crossover observed by x-ray spectroscopy on isolated fe(ii) complexes on gold. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 4, 1546–1552 (2013).

Okuyama, H. et al. Adsorbed states of chlorophenol on cu(110) and controlled switching of single-molecule junctions. J. Chem. Phys. 144, 244703 (2016).

Siegert, B., Donarini, A. & Grifoni, M. Nonequilibrium spin crossover in copper phthalocyanine. Phys. Rev. B 93, 121406 (2016).

Karan, S. et al. Shifting the voltage drop in electron transport through a single molecule. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 016802 (2015).

Heinrich, B. W., Braun, L., Pascual, J. I. & Franke, K. J. Tuning the magnetic anisotropy of single molecules. Nano Lett. 15, 4024–4028 (2015).

Gauyacq, J.-P., Lorente, N. & Novaes, F. D. Excitation of local magnetic moments by tunneling electrons. Prog. Surf. Sci. 87, 63–107 (2012).

Ternes, M. Spin excitations and correlations in scanning tunneling spectroscopy. New. J. Phys. 17, 063016 (2015).

Hewson, A. C. The Kondo Problem to Heavy Fermions. (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England, 1997).

Donati, F. et al. Magnetic remanence in single atoms. Science 352, 318–321 (2016).

Leuenberger, M. N. & Loss, D. Quantum computing in molecular magnets. Nature 410, 789–793 (2001).

Hirjibehedin, C. F., Lutz, C. P. & Heinrich, A. J. Spin coupling in engineered atomic structures. Science 312, 1021–1024 (2006).

Zyazin, A. S. et al. Electric field controlled magnetic anisotropy in a single molecule. Nano. Lett. 10, 3307–3311 (2010).

Parks, J. J. et al. Mechanical control of spin states in spin-1 molecules and the underscreened kondo effect. Science 328, 1370–1373 (2010).

Bryant, B., Spinelli, A., Wagenaar, J. J. T., Gerrits, M. & Otte, A. F. Local control of single atom magnetocrystalline anisotropy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 127203 (2013).

Oberg, J. C. et al. Control of single-spin magnetic anisotropy by exchange coupling. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 64–68 (2014).

Dubout, Q. et al. Controlling the spin of co atoms on pt(111) by hydrogen adsorption. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 106807 (2015).

Khajetoorians, A. A. et al. Tuning emergent magnetism in a hund’s impurity. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 958–964 (2015).

Ormaza, M. et al. Efficient spin-flip excitation of a nickelocene molecule. Nano Lett. 17, 1877–1882 (2017).

Otte, A. F. et al. The role of magnetic anisotropy in the kondo effect. Nat. Phys. 4, 847–850 (2008).

Žitko, R., Peters, R. & Pruschke, Th Splitting of the kondo resonance in anisotropic magnetic impurities on surfaces. New. J. Phys. 11, 053003 (2009).

Hurley, A., Baadji, N. & Sanvito, S. Perturbative approach to the kondo effect in magnetic atoms on nonmagnetic substrates. Phys. Rev. B 84, 115435 (2011).

Korytár, R., Lorente, N. & Gauyacq, J.-P. Many-body effects in magnetic inelastic electron tunneling spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 85, 125434 (2012).

Žitko, R., Peters, R. & Pruschke, Th Properties of anisotropic magnetic impurities on surfaces. Phys. Rev. B 78, 224404 (2008).

Misiorny, M., Weymann, I. & Barnaś, J. Underscreened kondo effect in s=1 magnetic quantum dots: exchange, anisotropy, and temperature effects. Phys. Rev. B 86, 245415 (2012).

Bachellier, N. et al. Unveiling nickelocene bonding to a noble metal surface. Phys. Rev. B 93, 195403 (2016).

Limot, L., Kröger, J., Berndt, R., Garcia-Lekue, A. & Hofer, W. A. Atom transfer and single-adatom contacts. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 126102 (2005).

Heinrich, B. W., Rastei, M. V., Choi, D.-J., Frederiksen, T. & Limot, L. Engineering negative differential conductance with the cu(111) surface state. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 246801 (2011).

Schull, G., Dappe, Y. J., González, C., Bulou, H. & Berndt, R. Charge injection through single and double carbon bonds. Nano. Lett. 11, 3142–3146 (2011).

Zhang, Y.-h, Wahl, P. & Kern, K. Quantum point contact microscopy. Nano. Lett. 11, 3838–3843 (2011).

Loth, S. et al. Controlling the state of quantum spins with electric currents. Nat. Phys. 6, 340–344 (2010).

Delgado, F., Palacios, J. J. & Fernández-Rossier, J. Spin-transfer torque on a single magnetic adatom. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 026601 (2010).

Novaes, F. D., Lorente, N. & Gauyacq, J.-P. Quenching of magnetic excitations in single adsorbates at surfaces: Mn on cun/cu(100). Phys. Rev. B 82, 155401 (2010).

Chen, X. et al. Probing superexchange interaction in molecular magnets by spin-flip spectroscopy and microscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 197208 (2008).

Tsukahara, N. et al. Adsorption-induced switching of magnetic anisotropy in a single iron(ii) phthalocyanine molecule on an oxidized cu(110) surface. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 167203 (2009).

Gauyacq, J.-P., Novaes, F. D. & Lorente, N. Magnetic transitions induced by tunneling electrons in individual adsorbed m-phthalocyanine molecules (m = Fe and co). Phys. Rev. B 81, 165423 (2010).

Frota, H. O. Shape of the kondo resonance. Phys. Rev. B 45, 1096–1099 (1992).

Choi, D.-J., Rastei, M. V., Simon, P. & Limot, L. Conductance-driven change of the kondo effect in a single cobalt atom. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 266803 (2012).

Choi, D.-J. et al. Kondo resonance of a co atom exchange coupled to a ferromagnetic tip. Nano Lett. 16, 6298–6302 (2016).

Choi, D.-J., Abufager, P., Limot, L. & Lorente, N. From tunneling to contact in a magnetic atom: The non-equilibrium kondo effect. J. Chem. Phys. 146, 092309 (2017).

Goldhaber-Gordon, D. et al. From the kondo regime to the mixed-valence regime in a single-electron transistor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 5225–5228 (1998).

van der Wiel, W. G. et al. The kondo effect in the unitary limit. Science 289, 2105–2108 (2000).

Yi, Z. et al. Tuning the magneto-transport properties of nickel−cyclopentadienyl multidecker clusters by molecule−electrode coupling manipulation. ACS Nano 4, 2274–2282 (2010).

Ormaza, M. et al. On-surface engineering of a magnetic organometallic nanowire. Nano. Lett. 16, 588–593 (2016).

Horcas, I. et al. Wsxm: a software for scanning probe microscopy and a tool for nanotechnology. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 78, 013705 (2007).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 47, 558 (1993).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for open-shell transition metals. Phys. Rev. B 48, 13115 (1993).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758 (1999).

Hafner, J. Ab-initio simulations of materials using vasp: density-functional theory and beyond. J. Comput. Chem. 29, 2044–2078 (2008).

Soler, J. M. et al. The siesta method for ab initio order- n materials simulation. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 14, 2745 (2002).

Brandbyge, M., Mozos, J. L., Ordejón, P., Taylor, J. & Stokbro, K. Density-functional method for nonequilibrium electron transport. Phys. Rev. B 65, 165401 (2002).

Grimme, S. Semiempirical gga-type density functional constructed with a long-range dispersion correction. J. Comput. Chem. 27, 1787–1799 (2006).

Abufager, P. N., Robles, R. & Lorente, N. Fecocp3 molecular magnets as spin filters. J. Phys. Chem. C 119, 12119–12129 (2015).

Rivero, P. et al. Systematic pseudopotentials from reference eigenvalue sets for DFT calculations: Pseudopotential files. Data in Brief 3, 21-23 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work has been supported by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (Grant Nos. ANR-13-BS10-0016, ANR-11-LABX-0058 NIE, ANR-10-LABX-0026 CSC) the ANPCyT project PICT Bicentenario No. 1962, the CONICET project PIP 0667, and the UNR project PID ING235. We acknowledge computer time provided by the CCT-Rosario Computational Center and the Computational Simulation Center (CSC) for Technological Applications, members of the High Performance Computing National System (SNCAD, MincyT-Argentina). Financial support from MINECO MAT2015-66888-C3-2-R and FEDER funds is also gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.O., B.V., N.B. and L.L. carried out the experiments. M.O. and L.L. analyzed the experiments. P.A., N.L. and M.-L.B. performed the DFT calculations. M.O. and L.L. wrote the manuscript with comments of all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ormaza, M., Abufager, P., Verlhac, B. et al. Controlled spin switching in a metallocene molecular junction. Nat Commun 8, 1974 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-02151-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-02151-6

This article is cited by

-

Evidence for spinarons in Co adatoms

Nature Physics (2023)

-

Tuning hydrogenation chemistry of Pd-based heterogeneous catalysts by introducing homogeneous-like ligands

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Reversible switching of Kondo resonance in a single-molecule junction

Nano Research (2022)

-

Iron phthalocyanine on Au(111) is a “non-Landau” Fermi liquid

Nature Communications (2021)

-

Vibron-assisted spin excitation in a magnetically anisotropic molecule

Nature Communications (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.