Abstract

The rise in antibiotic resistance is a major threat for human health. Basidiomycete fungi represent an untapped source of underexploited antimicrobials, with pleuromutilin—a diterpene produced by Clitopilus passeckerianus—being the only antibiotic from these fungi leading to commercial derivatives. Here we report genetic characterisation of the steps involved in pleuromutilin biosynthesis, through rational heterologous expression in Aspergillus oryzae coupled with isolation and detailed structural elucidation of the pathway intermediates by spectroscopic methods and comparison with synthetic standards. A. oryzae was further established as a platform for bio-conversion of chemically modified analogues of pleuromutilin intermediates, and was employed to generate a semi-synthetic pleuromutilin derivative with enhanced antibiotic activity. These studies pave the way for future characterisation of biosynthetic pathways of other basidiomycete natural products in ascomycete heterologous hosts, and open up new possibilities of further chemical modification for the growing class of potent pleuromutilin antibiotics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pleuromutilin is a diterpene natural product with antimicrobial properties, whose tricyclic skeleton has served as a precursor for semi-synthetic derivatives used in veterinary and human medicine. These antibiotics are active on Gram-positive bacteria and their mode of action relies on binding to the bacterial ribosome at the level of the peptidyl transferase centre, therefore inhibiting protein synthesis1. Pleuromutilin was first discovered by Kavanagh et al.2 from the two basidiomycete fungi Pleurotus mutilis (synonymous to Clitopilus scyphoides f. mutilus) and Pleurotus passeckerianus (synonymous to Clitopilus passeckerianus). It is now known to be also produced by a number of other related species3 and its chemical structure and cyclisation mechanism (Fig. 1a) were elucidated by independent work conducted by Arigoni4, 5 and Birch et al.6. The semi-synthetic pleuromutilin analogues tiamulin and valnemulin (Fig. 1a) have been used for over three decades to treat economically important infections in swine and poultry7,8,9,10 without showing any significant development of resistance in their target bacteria. Retapamulin (Fig. 1a), another pleuromutilin derivative, was approved in 2007 for the use in human medicine as a topical treatment for impetigo and other skin infections, being also active on methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)11. In recent years extensive research including structure–activity relationship (SAR) studies have been conducted with the aim of generating new orally available pleuromutilin derivatives to be used systemically in human medicine to treat acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections12, 13, as well as multidrug-resistant tuberculosis14, with more than a thousand compounds being synthesised15.

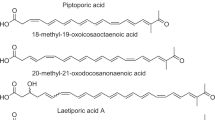

Pleuromutilin commercial derivatives and proposed cyclisation mechanism. a Structure of pleuromutilin and its commercial derivatives. b Outline of cyclisation to the pleuromutilin tricyclic scaffold, as reported by Arigoni4, 5 and Birch et al.6. The class II terpene synthase domain of Pl-Cyc promotes ring contraction during the protonation-dependent cyclisation of GGPP. The class I terpene synthase domain then catalyses formation of the 8-membered ring through ionisation-dependent dephosphorylation. Trapping with water introduces the first hydroxy group of the molecule at C-14 of the tricyclic scaffold

Since an increasing number of semi-synthetic derivatives of this diterpene antibiotic are being produced, understanding the biosynthetic pathway to pleuromutilin is an essential requirement for the effective and robust large-scale production of the natural product for use as starting material in these synthetic endeavours. The biosynthetic pathway to pleuromutilin has so far only been inferred through limited feeding experiments of the producing fungi with isotope-labelled predicted precursors16, 17, but a full picture of the pathway and a genetic characterisation of the enzymes involved in catalysis of each step of the biosynthesis are still lacking.

Biosynthetic pathways of fungal secondary metabolites are often characterised through generation of silenced or knockout mutant strains, where downregulation of biosynthetic genes or targeted-gene-deletion lead to accumulation of intermediates, as recently shown by Lin et al.18 for the pathway of the communesins. Heterologous expression of the biosynthetic genes for a secondary metabolite of interest in a filamentous fungus secondary host is also an established alternative for characterising gene function, as reviewed by Lazarus et al.19 and Alberti et al.20. Aspergilli and other physiologically well-characterised filamentous fungi are commonly employed for this purpose, as effective engineering toolboxes are available for their transformation. Among these, Aspergillus oryzae is known to have a low background in secondary metabolite production, despite having the potential for producing the building blocks for all main fungal secondary metabolites. A. oryzae has been successfully employed to recreate partial or total biosynthesis of natural products from other ascomycete fungi, such as the polyketide (PK) citrinin21, the polyketide–non-ribosomal peptide (PK–NRP) hybrid tenellin22, non-ribosomal peptide (NRP) siderophores such as ferrirhodin23, the indole-diterpene paxilline24, the diterpene aphidicolin25 and the meroterpenoid pyripyropene26.

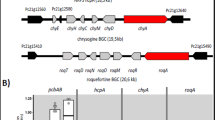

The gene cluster for the antibiotic pleuromutilin (1) was recently isolated in C. passeckerianus 27. Total de novo biosynthesis of 1 was achieved through the expression of the entire gene cluster in the secondary host A. oryzae, proving that the seven genes isolated were sufficient for biosynthesis of the diterpene antibiotic. However, this still did not provide insights into the function of each individual gene, nor on the nature of the intermediate compounds produced along the pathway. We report here genetic characterisation of the steps involved in the biosynthesis of 1, through a logical stepwise expression of genes from the pleuromutilin gene cluster in A. oryzae, coupled with isolation and detailed structural elucidation of the pathway intermediates by spectroscopic methods and comparison with synthetic standards. This pathway engineering approach has given insights into pleuromutilin biosynthesis and creation of a panel of A. oryzae strains designed to accumulate each pathway intermediate as a final product. Furthermore, full elucidation of a biosynthetic pathway of a basidiomycete natural product has been uncovered using an ascomycete secondary host. We envisage our work will pave the way for future characterisation of biosynthetic pathways of other basidiomycete natural products in ascomycete heterologous hosts, bypassing the need for genetic manipulation of intractable basidiomycete species. Moreover, in industrial production of antibiotics, replacing chemical synthesis steps with enzymatic biosynthesis represents an appealing and inexpensive alternative, and is considered a way of reducing manufacturing costs20. Here we show that our heterologous system can also be employed as a chassis to generate semi-synthetic derivatives of pleuromutilin, where a suitably engineered A. oryzae strain accepts a chemically modified pleuromutilin intermediate and takes the pathway to completion. This work led to generation of a semi-synthetic derivative of 1, which exhibited enhanced antibiotic activity against Bacillus subtilis.

Results

Analysis of gene silencing for pathway elucidation

Silencing of genes is a recognised molecular tool employed to study gene function in fungi, as shown for example by Nakayashiki et al.28 for the ascomycete model Magnaporthe oryzae. Since silencing of the genes of the pleuromutilin cluster was previously established in C. passeckerianus 29, we attempted detection of pleuromutilin intermediates from the extracts of the silenced lines for the pleuromutilin biosynthetic genes generated by Bailey et al.27. However, whilst pleuromutilin production ceased in the transformants, surprisingly no accumulation of pleuromutilin precursors could be detected from the crude extracts. RT-PCR from RNA extracted under normal production conditions failed to generate any products relating to pleuromutilin pathway genes—even those genes that were not targeted in the silencing experiment (Supplementary Fig. 1). This suggested that silencing of individual genes from the cluster triggered the downregulation of all the other genes known to be involved in biosynthesis of pleuromutilin. Since gene silencing was not a suitable means to achieve detailed functional characterisation of the genes of the pleuromutilin cluster in C. passeckerianus, instead we set out to undertake stepwise heterologous expression in the secondary host A. oryzae to build the pathway.

A diterpene synthase creates 14-hydroxytricyclic terpene 2

In order to heterologously express the genes of the pleuromutilin cluster in A. oryzae, we generated expression vectors based on the plasmids developed by Pahirulzaman et al.30. Because of the high intron density in basidiomycete genes and possibilities of mis-splicing from genomic clones, cDNA of these genes was used to construct the expression cassettes (see Supplementary Methods for details on vectors construction). Arigoni5 and Birch et al.6 showed that biosynthesis of pleuromutilin (1) proceeds via cyclisation of geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP) to generate a C-14 carbocation, which is trapped with water to give 2 (Fig. 1b). This proposed cyclisation mechanism has been supported by isotopic labelling studies; for instance, Arigoni reported incorporation of label with [2-14C]-mevalonate at C-3, C-7, C-13 and C-17 in pleuromutilin, fully consistent with the proposed cyclisation mechanism5. The gene cluster for 1 from C. passeckerianus contains both a pathway-specific geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase (Pl-ggs) gene, expected to provide GGPP, and a cyclase (or diterpene synthase, Pl-cyc) gene27. On the basis of homology searches, the Pl-cyc was inferred to encode a bifunctional diterpene synthase, which catalyses the protonation-dependent cyclisation of GGPP—promoted by the class II terpene synthase domain of the enzyme—as well as the ionisation-dependent dephosphorylation reaction—catalysed by the class I terpene synthase domain (Fig. 1b).

To investigate the first step in biosynthesis of 1, the cDNA of Pl-ggs—for putative increased production of GGPP—and Pl-cyc genes from C. passeckerianus were co-expressed in A. oryzae NSAR1, generating the transformant strain A. oryzae GC (see Table 1 for full a list of the strains generated, and Supplementary Methods for A. oryzae transformation and analysis of transformants). Reverse-phase HPLC failed to detect any new products in A. oryzae GC in comparison to untransformed controls, however a new compound was apparent by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) (Supplementary Fig. 2). Preparative TLC was used to purify the product, yielding 5 mg from 1 L of culture. The chemical ionisation (CI) mass spectrum gave m/z [M + H]+ 291.2688 (C20H35O) and the structure of 14-alcohol 2 was elucidated by extensive NMR studies (see Supplementary Figs. 3, 5 and 7–10 for NMR spectra and Supplementary Table 1 for NMR assignment and chemical ionisation mass spectrometry (CIMS) data).

To confirm the structure of alcohol 2 an authentic sample was prepared from commercially available tiamulin (Fig. 2). Hydrolysis of tiamulin gave mutilin 5 which was protected as the 14-monosilyl ether 8. The regiocontrol in the protection step was confirmed by conversion of alcohol 8 to acetate 9 which showed a characteristic downfield shift of the signal assigned to 11-H in the 1H-NMR spectrum. Following reduction of the 3-ketone to alcohol 10, the 19,20-alkene was temporarily protected via hydroboration and selective esterification of the resultant primary alcohol giving 12. The 3- and 11-hydroxy groups were removed via radical reduction and then pivoyl ester 13 was reduced to alcohol 14. Following dehydration then deprotection of the silyl ether 15, the target alcohol 2 was isolated. The 1H- and 13C-NMR spectra of the synthetic sample 2 (see Supplementary Figs. 4 and 6 for NMR spectra) were identical to those of alcohol 2 isolated from extracts from A. oryzae GC, confirming the structure of the natural product.

Hence, we can conclude that heterologous expression in A. oryzae of the Pl-ggs and Pl-cyc genes from the pleuromutilin gene cluster gives alcohol 2 as the first cyclic intermediate on the biosynthetic pathway to pleuromutilin. A similar reaction is observed also in the first step of biosynthesis of aphidicolin, where the aphidicolan-16β-ol synthase encoded by the PbACS gene catalyses cyclisation of GGPP to give a tetracyclic product that contains a hydroxyl function25. Like other fungal diterpene gene clusters, such as that for aphidicolin in Phoma betae 31, the gene cluster for 1 contains a pathway-specific Pl-ggs gene27, presumably to provide increased levels of GGPP25, the 20-carbon precursor of diterpenes that comes from isopentenyl diphosphate and dimethylallyl diphosphate.

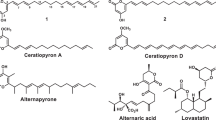

Characterisation of later steps of pleuromutilin biosynthesis

With a heterologous system established for the generation of the first tricyclic biosynthetic intermediate (2) encountered along the pathway, we aimed to characterise further metabolites produced along the pathway. The gene Pl-p450-1—coding for a putative Cytochrome P450 monooxygenase27—was expressed heterologously in the Pl-ggs+Pl-cyc strain A. oryzae GC, generating strain GCP1. Analysis of extracts by both TLC and HPLC revealed a new product (Supplementary Fig. 11), which was purified yielding 10 mg from 1 L of culture of 11,14-diol 3. The 1H-NMR spectrum of 3 displayed characteristic methine signals at δ 3.33 (d, J 6.4 Hz) and δ 4.34 (d, J 8.3, Hz) (see Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 12) which on comparison with the spectrum of mutilin, the 11,14-dihydroxy-3-ketone 5, correlated well with the signals assigned to 11-H and 14-H respectively. Hence the structure was tentatively assigned as 11,14-diol 3, which was confirmed by further extensive NMR studies combined with MS (see Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 11 for HPLC–MS, Supplementary Figs. 12–16 and Supplementary Table 2 for NMR characterisation of 3).

De novo production of pleuromutilin intermediates. a Proposed biosynthetic pathway to 1 in Clitopilus passeckerianus. b HPLC chromatograms showing de novo production of pleuromutilin intermediates in Aspergillus oryzae strains. (i) A. oryzae GCP1, (ii) A. oryzae GCP1P2, (iii) A. oryzae GCP1P2S, (iv) A. oryzae GCP1P2SA and (v) A. oryzae NSAR1 (recipient strain). Traces were recorded with evaporative light scattering detector (ELSD)

Co-expression of Pl-p450-1 and Pl-p450-2 in the A. oryzae strain that harboured Pl-ggs and Pl-cyc gave the transformant strain GCP1P2. A product (18 mg from 1L of culture) that was absent in strain GC was detected by HPLC and its structure assigned as triol (4) by high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) combined with 1D and 2D NMR (see Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 17 for HPLC–MS and Supplementary Figs. 18, 20 and 22–24 and Supplementary Table 3 for NMR data and Electrospray ionization (ESI)-HRMS). To confirm the proposed structure of triol 4, a synthetic sample was prepared by reduction of mutilin 5 (see Fig. 2 and Supplementary Figs. 19 and 21 for NMR spectra of synthetic 4), and the stereochemistry of the 3-hydroxy group established by nOe via irradiation of the signal assigned to 3-H (δ 4.54) leading to enhancements of the signals assigned to 2α-H, 4-H and 15-H3 (Supplementary Figs. 25 and 26).

For the conversion of triol 4 to pleuromutilin, oxidation of the 3-hydroxy group is required and the product of the gene Pl-sdr, predicted from bioinformatics analysis to be a short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase27 was proposed to catalyse this transformation. Hence an expression cassette for Pl-sdr along with Pl-p450-1 and Pl-p450-2 was transformed into the A. oryzae GC strain. Following purification of the extract by HPLC–MS the expected 3-ketone, mutilin (5) (15 mg from 1 L of culture) was isolated and fully characterised by both spectroscopic methods and comparison with an authentic sample prepared by semi-synthesis (see Fig. 4a, 4b and Supplementary Fig. 27 for HPLC–MS of 5, Supplementary Figs. 28, 30 and 32–34 and Supplementary Table 4 for NMR and ESI-HRMS data of 5, and Supplementary Figs. 29 and 31 for NMR spectra of synthetic sample).

To complete the biosynthesis of pleuromutilin (1) acetylation of the 14-alcohol to acetate 6, previously isolated from C. passeckerianus 32, followed by hydroxylation of the acetate is required. The gene cluster for 1 includes a predicted acetyl transferase (Pl-atf)27 and an additional P450 oxidoreductase (Pl-p450-3). Thus an A. oryzae transformant expressing all genes from the pleuromutilin cluster except Pl-p450-3 was generated, called GCP1P2SA, and the expected 14-acetate 6 was isolated (6 mg from 1 L of culture) and characterised (see Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 35 for HPLC–MS, and Supplementary Figs. 36–40 and Supplementary Table 5 for NMR and ESI-HRMS data). Furthermore, expression of all seven genes of the cluster, including Pl-p450-3 gave pleuromutilin 1 as the final product of the pathway (Fig. 4a)27.

Generation of bioactive derivatives of 1 within A. oryzae

In order to study the metabolism of pleuromutilin intermediates to 1, as well as to carry out bio-conversion of chemically modified analogues into pleuromutilin derivatives, we further established A. oryzae as a platform to carry out selected late steps in pleuromutilin biosynthesis. We validated our system by converting 5 into 1 upon culturing of strain AP3 (harbouring Pl-atf and Pl-p450-3 from C. passeckerianus) in the presence of 5 (100 mg L−1) (see Supplementary Figs. 41 and 42 for NMR spectra). Interestingly, triol 4—accumulated in strain GCP1P2—has not been detected previously in extracts of C. passeckerianus or other pleuromutilin-producing fungi. Hence to gain evidence that 4 is an intermediate in the biosynthesis of 1 a feeding study was conducted in the non-pleuromutilin producing A. oryzae SAP3 strain (expressing Pl-sdr, Pl-atf and Pl-p450-3 from C. passeckerianus, involved in the final three steps of the pathway). SAP3 was cultured in the presence of 4 (100 mg L−1), which was converted to both acetate 6 and pleuromutilin 1 (see Supplementary Figs. 43–46 for NMR spectra) in accord with triol 4 being an intermediate in pleuromutilin biosynthesis.

Once we established a system for conversion of pleuromutilin intermediates into pleuromutilin within A. oryzae, we further investigated the capability of this chassis to generate semi-synthetic analogues of 1 upon feeding with chemically modified analogues of the naturally occurring intermediates. In order to do so, we first prepared enone 18 starting from tiamulin (see Supplementary Fig. 47 for chemical synthesis leading to 18). We then cultured A. oryzae strain AP3 (containing Pl-atf and Pl-p-450-3 genes from C. passeckerianus) in the presence of 18 (30 mg in 300 mL culture broth), and confirmed the conversion of the enone into its ester 20 (18 mg, 51%) and hydroxy ester 21 (8 mg, 23%) (see Fig. 5a for a scheme of the bio-conversion, and Supplementary Figs. 48–51 for NMR spectra of the purified products). We thus investigated the antimicrobial activity of these two semi-synthetic derivatives against B. subtilis via plate-based bioassay (see Supplementary Methods for details on the antimicrobial bioassay procedure). The ester 20 produced an inhibition zone on the growth of B. subtilis of 12.7 ± 0.6 mm (see Fig. 5b and Supplementary Table 6), comparable to that of pleuromutilin 1 (12.8 ± 0.8 mm) and higher than that of 6 (10.3 ± 0.3 mm). Remarkably, the hydroxy ester 21 generated an inhibition zone on the growth of B. subtilis of 15.7 ± 1.8 mm, which was greater than that of both naturally occurring 1 and 6, as well as of that of its precursor 18 (8.0 ± 0.0 mm). Each antimicrobial bioassay was carried out in triplicate.

Semi-synthetic bioactive pleuromutilin derivatives. a Bio-conversion of the enone 18 into its ester 20 and hydroxy ester 21. b Antimicrobial activity of the semi-synthetic derivatives 20 and 21 against B. subtilis, compared to that of their precursor 18, and the naturally occurring 1 and 6. Error bars represent standard deviation of the bacterial growth inhibition zone calculated from three independent replicates

Discussion

Antimicrobial substances produced by microorganisms are a valuable resource for the development of semi-synthetic antibiotics. The diterpene antibiotic pleuromutilin has provided leads for the only commercial antibiotic produced from a basidiomycete fungus, specifically from C. passeckerianus and other related species3, and has led to the generation of semi-synthetic derivatives7, 8, 10 for human and veterinary use. The ongoing efforts towards the development of pleuromutilin analogues to be used systemically in human medicine suggests that this class of antibiotics is yet to be exploited to its full potential12,13,14.

In this study, we have shown genetic characterisation of all the steps involved in pleuromutilin biosynthesis from GGPP by rational heterologous expression in A. oryzae coupled with isolation and detailed structural elucidation of the pathway intermediates by spectroscopic methods and comparison with synthetic standards, as well as feeding purified intermediates into suitably engineered host strains. A first attempt to characterise the biosynthesis of pleuromutilin (1) via gene silencing in the native producer C. passeckerianus failed to return any accumulation of precursors. Transcript titres assessed by RT-PCR showed this was due to the downregulation of all genes of the cluster upon silencing of individual genes. This was unexpected, although a similar occurrence has been reported in other fungal secondary metabolite pathways33. As an alternative approach to characterise the biosynthetic pathway, and with the knowledge that full pleuromutilin production could be supported in A. oryzae 27, we adopted stepwise heterologous expression of the genes of the cluster for 1. Similar strategies have been successfully employed to characterise other fungal secondary metabolite pathways21,22,23,24,25,26. This allowed us to show accumulation of each of the five intermediates progressing to biosynthesis of 1 (Fig. 4), including 3R,11S,14R-triol (4), showing that the C-3 keto is derived in a two-step reaction via a hydroxy intermediate requiring both Pl-p450-2 and Pl-sdr.

Heterologous expression in A. oryzae of the Pl-ggs and Pl-cyc genes from the pleuromutilin cluster provided convincing evidence that 14-alcohol 2 is the first tricyclic intermediate generated on the pathway, as previously proposed by Arigoni4. The cytochrome P450 oxidoreductases encoded by Pl-p450-1 and Pl-p-450-2 catalyse stereospecific hydroxylation of C-11 and C-3 respectively, and co-expression of Pl-ggs, Pl-cyc, Pl-p450-1 and Pl-p-450-2 in A. oryzae gave accumulation of the putative intermediate 4. Rather than being a shunt product, triol 4 was shown to be a precursor of 1, through a feeding experiment of an A. oryzae strain harbouring Pl-sdr, Pl-atf and Pl-p450-3, successfully yielding pleuromutilin. Isolation of mutilin (5) in A. oryzae GCP1P2S (Fig. 4) showed that 4 is further oxidised along the pathway by the product of the gene Pl-sdr, indicating that Pl-sdr is a short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase class of enzyme that catalyses regiospecific oxidation of the 3-hydroxy group to a ketone. The final intermediate in the biosynthesis of 1 was produced de novo in A. oryzae by adding the Pl-atf gene (encoding an acetyl transferase) to the heterologous system that was producing 5, achieving sole production of 14-acetate 6 in GCP1P2SA (Fig. 4). By inference this shows that Cytochrome Pl-p450-3 is responsible for hydroxylation of acetate 6 to pleuromutilin, as production of 1 was observed before27 when expressing all the seven genes of the pleuromutilin gene cluster in A. oryzae, including Pl-p450-3, which was lacking in A. oryzae GCP1P2SA yielding 6.

The re-creation of a linear biosynthetic pathway to 1 by stepwise gene addition, allowed us to prove the function of the genes of the cluster from C. passeckerianus, and showed that biosynthesis of a basidiomycete secondary metabolite and its intermediates can be studied in an ascomycete heterologous host. Furthermore, we report here a full conversion of each intermediate of the pathway to the next, with no bottleneck observed in any of the biosynthetic steps (Fig. 4b), showing that our system can allow for accumulation of each biosynthetic precursor in amounts sufficient for consequent purification and full characterisation. We envisage this approach could be employed in the future to characterise the biosynthesis of other basidiomycete secondary metabolites of pharmaceutical or agrochemical relevance.

In this study, we also showed that the heterologous platform recreated in the A. oryzae host can be employed to convert not only pleuromutilin intermediates into 1, but also chemically modified analogues into semi-synthetic derivatives, providing a robust and flexible chassis for semi-synthetic derivatisation of pleuromutilin. Using this system, the chemically modified enone 18 was successfully bio-converted into ester 20 and hydroxy ester 21 (Fig. 5), with the latter showing increased antibiotic activity over pleuromutilin against B. subtilis.

In current commercial production of pleuromutilin derivatives the C-14 side chain of the naturally occurring antibiotic is removed, then replaced with the synthetic side chain. Deployment of the A. oryzae transformant strain that accumulates mutilin 5 could find application in industrial production of commercial pleuromutilins. Furthermore, the observation that a suitably engineered A. oryzae strain can successfully take to completion the pathway when fed with chemically modified analogues of pleuromutilin intermediates, opens new avenues for obtaining useful semi-synthetic derivatives of this antibiotic, exploiting more fully the power of combining synthetic chemistry and synthetic biology.

Methods

Reagents and conditions for growth of microorganisms

All chemicals were purchased from either Sigma-Aldrich or Fisher Scientific, unless otherwise specified, and were of analytical grade. Ingredients for media were purchased from Oxoid or Formedium, unless otherwise specified. All media, solutions, glassware and plastic-ware were sterilised by autoclaving at 121 °C for 15 min before use. C. passeckerianus ATCC 34646, producer of pleuromutilin, was maintained on PDA plates (24 g L−1 potato dextrose broth, 15 g L−1 agar) at 25 °C. A. oryzae NSAR1 (genotype niaD−, sC−, ΔargB, adeA−)34, used as heterologous host, was maintained on MEA plates with appropriate supplements (15 g L−1 malt extract, 1.5 g L−1 arginine, 1.5 g L−1 methionine, 0.1 g L−1 adenine, 2 g L−1 ammonium sulphate, 15 g L−1 agar) at 28 °C. Saccharomyces cerevisiae BY4742 (genotype MATα, his3Δ1, leu2Δ0, lys2Δ0, ura3Δ0)35, used for homologous recombination-based construction of plasmids, was maintained on YPAD plates (10 g L−1 yeast extract, 20 g L−1 bactopeptone, 20 g L−1 d-glucose, 40 mg L−1 adenine hemisulfate, 15 g L−1 agar). Escherichia coli One Shot ccdB Survival 2 T1 competent cells (Life Technologies) were used for propagation of plasmids by standard procedures. LB agar plates (10 g L−1 NaCl, 10 g L−1 tryptone, 5 g L−1 yeast extract, pH 7) were used for growing E. coli at 37 °C.

Genetic engineering of fungal strains

Silenced lines of C. passeckerianus used in this study where those described in Bailey et al.27, where the antisense sequence of each gene of the pleuromutilin cluster was placed under control of the Agaricus bisporus gpdII promoter and expressed in C. passeckerianus. Expression vectors for A. oryzae to contain the genes of the pleuromutilin cluster were constructed through homologous recombination in yeast following the procedure described by Ma et al.36. The seven genes of the pleuromutilin gene cluster—Pl-ggs, Pl-cyc, Pl-p450-1, Pl-p450-2, Pl-p450-3, Pl-atf and Pl-sdr—were amplified using high-fidelity PCR from the cDNA of C. passeckerianus and cloned in pJET 1.2 cloning vectors (see Supplementary Methods for details on cloning of the genes of the pleuromutilin cluster). Plasmids pTYGSarg, pTYGSade and pTYGSbar30 were used as backbones to construct expression vectors with the intron-free genes of the pleuromutilin cluster (plasmid maps and details of construction of expression vectors are in Supplementary Methods), which were used to transform A. oryzae NSAR1 and derived transformant strains. Protoplast-mediated transformation of A. oryzae was carried out following an adapted protocol from the one described by Halo et al.37. Details on the A. oryzae transformation procedure are reported in Supplementary Methods. The vector pTYGSargGGSCyc (which included Pl-ggs and Pl-cyc) was used for transformation of A. oryzae NSAR1, generating strain GC (producer of 2). Further transformation of GC with pTYGSadeP1 (containing Pl-p450-1) achieved production of strains GCP1 (producer of 3). Likewise, transformation of GC with pTYGSadeP1P2 (containing Pl-p450-1 and Pl-p450-2) returned strains GCP1P2 (producer of 4). A combination of pTYGSadeP1P2 and pTYGSbarSDR (containing Pl-sdr) was introduced into GC to produce strain GCP1P2S (producer of 5), whereas a combination of pTYGSadeP1P2 and pTYGSbarATFSDR (containing Pl-atf and Pl-sdr) was used to transform strain GC to achieve GCP1P2SA (producer of 6). Strain AP3, used for feeding experiment with 5, was generated by transforming A. oryzae NSAR1 with a combination of pTYGSadeP3 (containing Pl-p450-3) and pTYGSbarATF (containing Pl-atf), whereas strain SAP3 used for feeding experiment with 4 was obtained by transforming A. oryzae NSAR1 with a combination of pTYGSadeP3 (containing Pl-p450-3) and pTYGSbarATFSDR (containing Pl-atf and Pl-sdr).

Synthetic chemistry

Selected proposed biosynthetic intermediates were synthesised as presented in Fig. 2 and described in the main text, in order to confirm by NMR the structure of the compounds produced de novo in engineered fungal strains, as well as to give standards for HPLC–MS. Enone 18 was synthesised as presented in Supplementary Fig. 47.

Chemical analysis on A. oryzae transformants

A. oryzae transformants were analysed for production of metabolites. Each transformant strain was grown in 100 mL of CMP medium (35 g L−1 Czapek-dox liquid, 20 g L−1 maltose, 10 g L−1 peptone) at 28 °C for 10 days prior to proceeding with organic extractions with ethyl acetate, concentrating the crude extract in vacuo and dissolving in methanol. For the A. oryzae strains GC, AP3 (fed with 5) and SAP3 (fed with 4), the crude extracts were analysed for detection of metabolites by using TLC. Fungal crude extracts were transferred to 20 × 20 cm TLC plates (TLC silica gel 60 F254; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), which were developed in petroleum spirit-ethyl acetate (9:1 for strain GC, 1:1 for strains AP3 and SAP3). This led to 5 mg of 2 from the crude extract of strain GC, 6 mg of 1 from the extract of AP3 (fed with 5), 4 mg of 1 and 3 mg of 6 from the extract of SAP3 (fed with 4). For the purification of the crude extract of AP3 fed with the synthetic analogue 18 (30 mg in 300 mL broth) flash column chromatography was employed, using a silica gel with pore size 60 Å and particle size 40–60 µm (Sigma Aldrich). Fractions were collected in glass tubes, pooled in a pre-weighed glass vial and concentrated in vacuo. Using this procedure, purification of 18 mg of acetate 20 and 8 mg of hydroxy acetate 21 was achieved. For all other strains the crude extracts were analysed with analytical HPLC–MS by using a Waters 2767 HPLC system with a Waters 2545 pump system, and a Phenomenex LUNA column (2.6 μ, C18, 100 Å, 4.6 × 100 mm) equipped with a Phenomenex Security Guard precolumn (Luna C5 300 Å). A reverse-phase HPLC with a gradient of solvents was used (A, HPLC grade H2O containing 0.05% formic acid; B, HPLC grade CH3CN containing 0.045% formic acid) with the following programme: 0 min, 10% B; 15 min, 90% B; 16 min 95% B; 17 min 95% B; 18 min 10% B, 20 min 10% B. Flow rate was set at 1 mL min−1. Preparative HPLC–MS was used to purify compounds from the crude extract of A. oryzae transformants that were absent in the A. oryzae control strain. For this purpose a 1-L culture of the chosen fungal strain was set up and extracted with the same conditions described when undertaking analytical HPLC–MS. Fractions that contained target compounds were purified using reverse-phase HPLC on a Waters mass-directed autopurification system with a Waters 2767 autosampler and Waters 2545 pump system, a Phenomenex LUNA column (5μ, C18, 100 Å, 10 × 250 mm) for reverse-phase chromatography, equipped with a Phenomenex Security Guard precolumn (Luna C5 300 Å), eluted at 16 mL min−1. A gradient of solvents was used (A, HPLC grade H2O containing 0.05% formic acid; B, HPLC grade CH3CN containing 0.045% formic acid) with the following programme: 0 min, 5% B; 2 min, 10% B; 20 min, 90% B; 21 min 95% B; 26 min 95% B; 27 min 5% B, 30 min 5% B. Specific fractions were collected in glass tubes, pooled in a pre-weighed glass vial and concentrated in vacuo. Using this procedure, purification of 10 mg of 3, 18 mg of 4, 15 mg of 5 and 6 mg of 6 was achieved. Details of the procedures used for ethyl acetate organic extractions, TLC, analytical and preparative HPLC–MS are also reported in Supplementary Methods.

Spectroscopic analyses of purified metabolites

The metabolites purified from A. oryzae transformants were characterised by NMR spectroscopy. The samples were dissolved in CDCl3 or CD3OD and spectra were obtained with an Agilent VNMRS500 spectrometer (1H 500 MHz, 13C 125 MHz). Chemical shifts were recorded in parts per million (ppm) and coupling constant (J) in Hz. Chemical shifts for 1H-NMR are reported relative to the proton resonance δ 7.26 of CHCL3 or δ 4.78 of CH3OH, whereas shifts for 13C-NMR are reported relative to the carbon resonance δ 77.16 of CDCl3. ESI-HRMS was performed with a Bruker Daltonics microTOF focus using positive ESI. Chemical ionisation mass spectrometry was performed with a VG/Micromass Autospec operated in positive mode. NMR spectra and ESI-HRMS/CIMS data for the metabolites produced de novo from the A. oryzae engineered strains are reported in Supplementary Information.

Bio-conversion of precursors into 1 and derivatives

Liquid cultures of AP3 and SAP3 were set up in 100 mL of CMP medium with the addition of 4 and 5 (100 mg L−1) respectively, and grown for 10 days at 28 °C prior to proceeding with organic extractions with ethyl acetate and concentration of the crude extracts in vacuo. TLC was used to purify 1 from the crude extract of strain AP3 (fed with 5), as well as 1 and 6 from the crude extract of strain SAP3 (fed with 4), and the structures confirmed by 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR. For bio-conversion of 18, liquid cultures of AP3 were set up in 100 mL of CMP medium with the addition of 18 (100 mg L−1). Organic extractions with ethyl acetate and concentration of the crude extract in vacuo were followed by column chromatography (10–20% EtOAc in petrol) for purification of 20 (23 mg, 67%) and 21 (14 mg, 39%). 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR were carried out to confirm the structures.

Data availability

All data is available from the authors upon reasonable request.

References

Davidovich, C. et al. Induced-fit tightens pleuromutilins binding to ribosomes and remote interactions enable their selectivity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 4291–4296 (2007).

Kavanagh, F., Hervey, A. & Robbins, W. J. Antibiotic substances from Basidiomycetes. VIII. Pleurotus multilus (Fr.) Sacc. and Pleurotus passeckerianus pilat. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 37, 570–574 (1951).

Hartley, A. J. et al. Investigating pleuromutilin-producing Clitopilus species and related basidiomycetes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 297, 24–30 (2009).

Arigoni, D. La struttura di un terpene di nuovo genere. Gazz. Chim. Ital. 92, 884–901 (1962).

Arigoni, D. Some studies in the biosynthesis of terpenes and related compounds. Pure Appl. Chem. 17, 331–348 (1968).

Birch, A. J., Holzapfel, C. W. & Rickards, R. W. The structure and some aspects of the biosynthesis of pleuromutilin. Tetrahedron 22, 359–387 (1966).

Burch, D. G., Jones, G. T., Heard, T. W. & Tuck, R. E. The synergistic activity of tiamulin and chlortetracycline: in-feed treatment of bacterially complicated enzootic pneumonia in fattening pigs. Vet. Rec. 119, 108–112 (1986).

Laber, G. & Schütze, E. In vivo efficacy of 81.723 hfu, a new pleuromutilin derivative against experimentally induced airsacculitis in chicks and turkey poults. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. (Bethesda) 7, 517–521 (1975).

Stipkovits, L. et al. The efficacy of valnemulin (Econor®) in the control of disease caused by experimental infection of calves with Mycoplasma bovis. Res. Vet. Sci. 78, 207–215 (2005).

Zhao, D. H. et al. Population pharmacokinetics of valnemulin in swine. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 37, 59–68 (2014).

Rittenhouse, S. et al. Selection of retapamulin, a novel pleuromutilin for topical use. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. (Bethesda) 50, 3882–3885 (2006).

Ling, C. et al. Design, synthesis, and structure–activity relationship studies of novel thioether pleuromutilin derivatives as potent antibacterial agents. J. Med. Chem. 57, 4772–4795 (2014).

Wang, X. et al. Novel pleuromutilin derivatives as antibacterial agents: synthesis, biological evaluation and molecular docking studies. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 22, 6166–6172 (2012).

Dong, Y.-J. et al. Synthesis of novel pleuromutilin derivatives. Part I: preliminary studies of antituberculosis activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 25, 1799–1803 (2015).

Novak, R. Are pleuromutilin antibiotics finally fit for human use? Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1241, 71–81 (2011).

Hasler, H. Neue Aspekte der Biosynthese von Pleuromutilin (PhD thesis, ETH Zurich, 1979).

Tsukagoshi, T., Tokiwano, T. & Oikawa, H. Studies on the later stage of the biosynthesis of pleuromutilin. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 71, 3116–3121 (2007).

Lin, H. C. et al. Elucidation of the concise biosynthetic pathway of the communesin indole alkaloids. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 127, 3047–3050 (2015).

Lazarus, C. M., Williams, K. & Bailey, A. M. Reconstructing fungal natural product biosynthetic pathways. Nat. Prod. Rep. 31, 1339–1347 (2014).

Alberti, F., Foster, G. D. & Bailey, A. M. Natural products from filamentous fungi and production by heterologous expression. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 101, 493–500 (2017).

Sakai, K., Kinoshita, H., Shimizu, T. & Nihira, T. Construction of a citrinin gene cluster expression system in heterologous Aspergillus oryzae. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 106, 466–472 (2008).

Heneghan, M. N. et al. First heterologous reconstruction of a complete functional fungal biosynthetic multigene cluster. ChemBioChem. 11, 1508–1512 (2010).

Munawar, A., Marshall, J. W., Cox, R. J., Bailey, A. M. & Lazarus, C. M. Isolation and characterisation of a ferrirhodin synthetase gene from the sugarcane pathogen Fusarium sacchari. ChemBioChem. 14, 388–394 (2013).

Tagami, K. et al. Reconstitution of biosynthetic machinery for indole-diterpene paxilline in Aspergillus oryzae. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 1260–1263 (2013).

Fujii, R. et al. Total biosynthesis of diterpene aphidicolin, a specific inhibitor of DNA polymerase α: heterologous expression of four biosynthetic genes in Aspergillus oryzae. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 75, 1813–1817 (2011).

Itoh, T. et al. Reconstitution of a fungal meroterpenoid biosynthesis reveals the involvement of a novel family of terpene cyclases. Nat. Chem. 2, 858–864 (2010).

Bailey, A. M. et al. Identification and manipulation of the pleuromutilin gene cluster from Clitopilus passeckerianus for increased rapid antibiotic production. Sci. Rep. 6, 25202 (2016).

Nakayashiki, H. et al. RNA silencing as a tool for exploring gene function in ascomycete fungi. Fungal Genet. Biol. 42, 275–283 (2005).

Kilaru, S., Collins, C. M., Hartley, A. J., Bailey, A. M. & Foster, G. D. Establishing molecular tools for genetic manipulation of the pleuromutilin-producing fungus Clitopilus passeckerianus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 7196–7204 (2009).

Pahirulzaman, K. A. K., Williams, K. & Lazarus, C. M. A toolkit for heterologous expression of metabolic pathways in Aspergillus oryzae. Methods Enzymol. 517, 241–260 (2012).

Toyomasu, T. et al. cloning of a gene cluster responsible for the biosynthesis of diterpene aphidicolin, a specific inhibitor of DNA polymerase α. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 68, 146–152 (2004).

Knauseder, F. & Brandl, E. Pleuromutilins. fermentation, structure and biosynthesis. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 29, 125–131 (1976).

Schumacher, J., Viaud, M., Simon, A. & Tudzynski, B. The Gα subunit BCG1, the phospholipase C (BcPLC1) and the calcineurin phosphatase co-ordinately regulate gene expression in the grey mould fungus Botrytis cinerea. Mol. Microbiol. 67, 1027–1050 (2008).

Jin, F. J., Maruyama, J., Juvvadi, P. R., Arioka, M. & Kitamoto, K. Development of a novel quadruple auxotrophic host transformation system by argB gene disruption using adeA gene and exploiting adenine auxotrophy in Aspergillus oryzae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 239, 79–85 (2004).

Brachmann, C. B. et al. Designer deletion strains derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C: a useful set of strains and plasmids for PCR-mediated gene disruption and other applications. Yeast 14, 115–132 (1998).

Ma, H., Kunes, S., Schatz, P. J. & Botstein, D. Plasmid construction by homologous recombination in yeast. Gene 58, 201–2016 (1987).

Halo, L. M. et al. Late stage oxidations during the biosynthesis of the 2-pyridone tenellin in the entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 17988–17996 (2008).

Acknowledgements

We thank Colin Lazarus for providing expression vectors for transformation of A. oryzae; Claudio Greco and Agnieszka Wozniak for assistance in NMR data collection; the NMR and MS Facilities and teams of the University of Bristol for data collection and helpful discussion. This work was financially supported by the University of Bristol (for F.A., P.M.H.), Conacyt (for E.R.V.), the EPSRC, Bristol Chemical Sciences Centre for Doctoral Training (EP/L015366/1) for a studentship to J.A.D., and Majlis Amanah Rakyat (for K.K.). We also thank the BBSRC and EPSRC for providing funding for equipment through the Centre for Synthetic Biology, BrisSynBio (grant BB/L01386X/1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.D.F. and A.M.B. coordinated the project and designed molecular biology research; C.L.W. designed synthetic chemistry research; P.M.H. performed silencing studies in C. passeckerianus; F.A. performed heterologous expression and characterisation of metabolites produced de novo in A. oryzae; E.R.V. performed chemical synthesis of biosynthetic analogues; K.K. performed antimicrobial bioassays and assisted in generation of engineered A. oryzae strains; J.A.D. performed chemical synthesis of enone analogue; F.A., J.A.D. and C.L.W. analysed spectral data; F.A. drafted the manuscript, with guidance and contributions from C.L.W., A.M.B. and G.D.F.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alberti, F., Khairudin, K., Venegas, E.R. et al. Heterologous expression reveals the biosynthesis of the antibiotic pleuromutilin and generates bioactive semi-synthetic derivatives. Nat Commun 8, 1831 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-01659-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-01659-1

This article is cited by

-

Current trends, limitations and future research in the fungi?

Fungal Diversity (2024)

-

Efficient exploration of terpenoid biosynthetic gene clusters in filamentous fungi

Nature Catalysis (2022)

-

Ten decadal advances in fungal biology leading towards human well-being

Fungal Diversity (2022)

-

Biosynthesis and regulation of terpenoids from basidiomycetes: exploration of new research

AMB Express (2021)

-

Streptomyces: host for refactoring of diverse bioactive secondary metabolites

3 Biotech (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.