Abstract

Magnetic reconnection is believed to be the main driver to transport solar wind into the Earth’s magnetosphere when the magnetopause features a large magnetic shear. However, even when the magnetic shear is too small for spontaneous reconnection, the Kelvin–Helmholtz instability driven by a super-Alfvénic velocity shear is expected to facilitate the transport. Although previous kinetic simulations have demonstrated that the non-linear vortex flows from the Kelvin–Helmholtz instability gives rise to vortex-induced reconnection and resulting plasma transport, the system sizes of these simulations were too small to allow the reconnection to evolve much beyond the electron scale as recently observed by the Magnetospheric Multiscale (MMS) spacecraft. Here, based on a large-scale kinetic simulation and its comparison with MMS observations, we show for the first time that ion-scale jets from vortex-induced reconnection rapidly decay through self-generated turbulence, leading to a mass transfer rate nearly one order higher than previous expectations for the Kelvin–Helmholtz instability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Earth’s magnetopause, across which the shocked solar wind (magnetosheath) particles are transported into the magnetosphere, consists of velocity and magnetic shears both of which coexist in many boundaries in natural magnetized collisionless plasmas. There are two dominant mechanisms, which transfer mass across such collisionless boundaries. When the boundaries have large magnetic shears, the dominant process is magnetic reconnection which causes very efficient transfer along the reconnected field lines1,2,3,4, while in the limit of super-Alfvénic velocity shear, the Kelvin–Helmholtz instability (KHI)5,6,7 is also believed to induce a considerable transport8,9,10,11,12,13,14. When considering a density asymmetry across the velocity shear, the unstable condition for the KHI is written as follows15.

where ρ s (s = 1, 2), U s and B s are mass density, bulk velocity, and magnetic field at each side across the boundary, respectively. Equation (1) predicts that when the magnetic field component parallel to k is sufficiently weak, the KHI develops nearly in the flow direction, which corresponds to tailward (anti-sunward) along the magnetopause16.

In this paper, we show results from a kinetic simulation under realistic magnetopause conditions obtained from the Magnetospheric Multiscale (MMS) spacecraft which feature a super-Alfvénic velocity shear and a weak magnetic shear to satisfy Eq. (1). Past theoretical and numerical studies of the magnetopause suggest that a type of reconnection process, which is induced by the compression of the pre-existing magnetic shear layer (current sheet) by the KHI vortex flow, can give rise to efficient plasma transport along the reconnected field lines17, 18. Hereafter we refer to this type of reconnection process13, 19,20,21,22 as vortex-induced reconnection (VIR). The new large-scale 3D simulation demonstrates the turbulent development of VIR within the tailward propagating Kelvin–Helmholtz (KH) vortex. This new turbulent phase of VIR is made possible by the larger system size, which permits the more realistic development of the ion-scale features driven by the VIR outflow jets.

Results

Evolution of the turbulent vortex layer

We employed the three-dimensional (3D) fully kinetic simulation code VPIC23, 24. The initial parameters are obtained during 0900–1130 UT on 8 September 2015 from the MMS spacecraft, which crossed the magnetopause from the magnetospheric to denser magnetosheath sides, and encountered quasi-periodic KH waves between the two sides25,26,27,28,29. The simulation was performed in Cartesian coordinates (x, y, z), in which y-direction is perpendicular to the magnetopause, x-direction is along the k-vector of the fastest growing KH mode, and z = x × y completes the system. Further details of the initial setup are given in the Methods section.

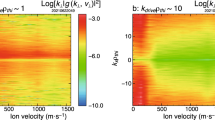

In this simulation, the equilibrium velocity shear drives a vortex structure as shown in Fig. 1a during the early non-linear growth phase of the KHI. In this phase (tα ~ 5), the ion-scale jets of the VIR are formed along the compressed current layer near the hyperbolic point where the vortex flow is converged (Fig. 1b). Here, 1/α=λ KH/V 0 is the time unit based on the linear growth rate of the KHI13, 22. At tα ~ 4.5, the electron-scale (less than the ion-inertial length d i) current sheet forms. At tα ~ 5, reconnection occurs at multiple sites and this primary reconnection forms ion-scale (~5d i scale) reconnection outflow jets along the current layer. Since these jets transport low-density plasmas originally located in the upper (+y) region, the density within the jets is lower than in the adjacent regions, which forms higher-density layers on the upper (low-density) side. At tα ~ 5.5, these ion-scale jet structures rapidly decay and produce a thicker turbulent mixing layer where clear high-density layers can no longer be seen. Figure 1c shows that at tα = 4.9, clear peaks of B y , U iy, and U ey powers can be seen at θ ~ θ ave, while at tα = 5.50, the powers of all the components are more widely scattered within θ < θ max. This indicates that the turbulent development of the secondary 3D tearing mode causes the rapid decay of the jet structures as shown in Fig. 1b.

Evolution of the ion-scale turbulent reconnection layer produced within the MHD-scale KH vortex. a 3D view of mixing surfaces13, 30 defined as F e = (n e1 − n e2)/(n e1 + n e2) = −0.99 and 0.99 with electron density contours in the x–y planes at z = 0 (=L z ) in an early non-linear growth phase of the KHI (tα = 4.90). The white curves in a show ion streamlines projected onto the x–y planes. b Zoom-in views of the 2D contours in the x–y plane at z = 0 of the ion density n i, the current density |J| with the in-plane magnetic field lines, and the ion bulk flow component U iL along with the compressed current layer from tα = 4.57 to tα = 5.88, showing the formation and turbulent decay of ion-scale reconnection signatures. The L′ and N′ directions marked in b show the L and N (parallel and perpendicular to the current layer) directions projected on the x–y plane, respectively. See the Methods section for more details of the LMN coordinates. c 2D power spectra (k x , k z ) of B y , U iy, and U ey at tα = 4.90 and 5.50. θ ave = tan−1((B in1 + B in2)/(B out1 + B out2)) in c is the averaged magnetic field angle between the two background regions, showing the expected peak angle satisfying the resonance condition k · B = 0 of the tearing mode within the boundary region. θ max in c is the maximum oblique angle of the magnetic field in the x–z plane that corresponds to the maximum shear angle of the magnetic field in the x–z plane. The powers of all components are cut off in θ > θ max, indicating the turbulent development of the 3D tearing mode is the main source of the magnetic field fluctuations as demonstrated in past 3D kinetic simulations of guide-field reconnection35, 36

As seen in Fig. 2a, the spectral power in the y-component (B y ) of the magnetic field is significantly enhanced over the electron (kd e ~ 1) to MHD (kd i < 1) scales in the early non-linear phase (compare the curves for tα = 3.27–3.81 and tα = 4.90–5.44). The B y spectrum for tα = 4.90–5.44, during which the 3D turbulence of the secondary tearing mode is well developed as seen in Fig. 1b, shows a power law with ~k −8/3 index for the ion (kd i ~ 1) and MHD (kd i < 1) scales and a steeper slope for smaller scales. A turbulent spectrum with a similar slope (k −8/3) produced by the secondary 3D tearing mode was seen in past 3D kinetic simulations of guide-field reconnection30. In this early non-linear phase, the spectra of the ion and electron flows show significant power enhancements in the ion scale (compare Fig. 2b, c) and clear power laws from the electron to ion scales with a similar index to B y (Fig. 2c). This supports the above scenario indicated from Fig. 1b, c, in which the structures of the initial ion-scale jets are disturbed by coupling with the turbulent growth of the secondary tearing mode. As seen in Fig. 2e, as the non-linear vortex flow develops, this ion-scale turbulent layer is engulfed into the MHD-scale vortex body, and in the late non-linear phase the whole vortex layer becomes turbulent with well-mixed plasmas. Correspondingly, the spectra in this late non-linear phase feature turbulent power laws with ~k −5/3 index from the ion to MHD scales for all U iy, U ey, and B y components (Fig. 2d). This turbulent evolution of the vortex layer leads to a significantly efficient plasma mixing as will be shown later.

Evolution of turbulent spectrum. a 1D power spectra (k x ) of averaged B y over tα = 3.27–3.81 (late linear phase), tα = 4.90–5.44 (early non-linear phase), and tα = 7.07–7.62 (late non-linear phase). b–d 1D power spectra of U iy, U ey, and B y averaged over tα = 3.27–3.81 (b) tα = 4.90–5.44 (c), and tα = 7.07–7.62 (d). The blue curves in b–d are the same ones as the curves shown in a. The vertical dashed lines in a–d indicate the wavelengths for kd i = 1 and kd e = 1 based on n 0 (=n 1) and n 2. Each curve in a–d is obtained by averaging U iy, U ey, and B y of 11 equally spaced time slices, which reduces the short-wavelength particle noise30. e Time evolution of the 3D view of mixing surfaces from the late linear (tα = 3.38) to late non-linear (tα = 7.95) growth phase of the KHI

Comparison with the MMS observations for the crossing of reconnection jet

Figure 3a shows 3D views of the surface of U iL = 0.76\(V_0^\prime\), while Fig. 3b shows 2D views of the surfaces of U iL = 0.76\(V_0^\prime\) and 0.69\(V_0^\prime\) in the x–y plane at z = L z(=0). Since the angle of the current layer from the background flow direction in the x–y plane (i.e., the angle between x and L′) is about 30°, the background flow velocity in the L-direction is about 0.5\(V_0^\prime\). In addition, since the peak \(\left| {B_L} \right|\) around the current layer is about 0.3B 0 (as will be shown in Fig. 4a), the expected peak speed of the reconnection jet for ions considering the background flow is about 0.5V 0 ± 0.3 V A ~ (0.5 ± 0.3)\(V_0^\prime\). Thus, the isosurface of U iL = 0.76 \(V_0^\prime\) (and 0.69 \(V_0^\prime\)) captures the structure of the ion reconnection jets growing in the positive L-direction. At both tα = 4.90 and 5.55, the jets extend in the L-direction with a few d i thickness in the N-direction. This 2D-like structure in the L–N plane extends in the M-direction over more than 8d i. The length of the jets in the L-direction at tα = 5.55 become 1.5–2 times longer than those at tα = 4.90.

Structure of the ion-scale reconnection jets. a 3D views at tα = 4.90 and tα = 5.22 (the times before the turbulent decay of the reconnection layer) of the ion-scale zoomed region (the same region shown in Fig. 1b). The 3D surfaces show the contour surface of U iL = 0.76\(V_0^\prime\), which represents the location and structure of the positive U iL jet in the 3D view. The 2D planes show the ion density in the x–y plane at z = L z ( = 0) and z = L z − 8d i. The directions of the unit vectors in the xyz system and the local coordinate (LMN) system along the compressed layer are indicated by black arrows. b The density and the M component of the current density contours in the x–y plane at z = L z (the same region as the upper slice in a). The mixing surfaces and the surfaces of U iL = 0.76\(V_0^\prime\) and 0.69\(V_0^\prime\) are shown in both the upper and bottom panels, while the in-plane field lines are shown only in the bottom panels. At both times, the reconnection jet extends in the L-direction with a few d i thickness in the N-direction. This jet structure in the L−N plane spreads in the M-direction over more than 8d i as shown in a. The peak speed and size of the jets in the L-direction at tα = 5.22 are larger than those at tα = 4.90. The density within the jets is lower, leading to the formation of higher-density layers on the magnetospheric (−N) side of the jets

Comparison with the in situ observation data from the MMS spacecraft for the crossing of reconnection jets in the KH wave events on 8 September 2015. a, b Virtual observation for the crossing of a positive U iL jet along the dashed lines shown in Fig. 3b (a) and in situ observations by the four MMS spacecraft for a 7 s interval from 10:29:26 UT (b) of the ion density, the ion bulk velocity U i , the magnetic field B, and the electron bulk velocity U e velocity components in the LMN system. The data for MMS1 were reported in Fig. 2 in ref. 27. The values in a and b are normalized by the initial (n 0 and B 0) and averaged background (n 0 = 25 cm−3 and B 0 = 74 nT) values in the magnetosheath region, respectively. Vertical lines indicate the location of the U iL peaks for orbits 1 (black) and 2 (blue) in a and MMS1 (black) and 4 (blue) in b. The yellow arrows indicate the intervals of the density dips. c The separation of the four MMS spacecraft on 10:29:26 UT in the LMN system in the 3D view and its projections into the L−N and M–N planes. The closed symbols show relative locations X s of the MMS spacecraft. The dashed arrows show the spacecraft paths assuming that the structures move past the MMS tetrahedron at a constant \(\left\langle {\bf V} \right\rangle\) (indicated by the magenta dashed lines in b) during this 7 s period. The open symbols and the solid lines show the expected locations \({\mathrm{X}}_{\mathrm{s}}^\prime\) = X s − \(\left\langle {\bf V} \right\rangle\)(t s – t 1) of the peak and the whole region of the positive U iL jet for each spacecraft relative to the time t 1 when MMS1 observed the U iL peak. Similarly, the yellow bars show the expected locations of the density dips

Figure 4a shows the virtual observation results in which the two probes separated by 1.5d i in the N-direction cross the positive U iL jet at tα = 5.22 as marked in Fig. 3b. Here, we assume that the jet structures shown at tα = 5.22 are not changed and propagate in the background flow direction (~x-direction) during the crossing by the virtual probes. As seen in Fig. 3b, both probes first observed the density peaks and then observed the U iL peaks with density dips during the crossing of the current layer. The amplitude of U eL at the U iL peaks (vertical lines) is similar to that of U iL, but the electron flows tend to have stronger electron-scale (<d i) fluctuations than the ion flows. The density dip for probe-2 which is closer to the X-line is ~1.5 times deeper and ~2 times shorter than that for probe-1, indicating that the lower density plasmas within the dips diffuse more strongly in the downstream region of the jets.

Figure 4b shows the observations from the four MMS spacecraft on 8 September 2015 in the same format as Fig. 4a. Although the data for MMS1 in this event have been reported in ref. 27, here we analyze the data from all four spacecraft. As seen in the simulation, all the spacecraft first observed the density peaks and then the U iL peaks with density dips while crossing the current layer. Notice here that the background ion velocities during this interval are similar among the four spacecraft. Assuming that the jet structures during this interval constantly propagate at the averaged background velocities \(\left\langle {\bf{V}} \right\rangle\) (magenta lines in Fig. 4b), we can estimate the locations of the U iL jets and their peaks relative to the U iL peak of MMS1 in the LMN system (Fig. 4c). The estimated locations of the jets for the MMS1 and 2 pair and the MMS3 and 4 pair are close in the L–N plane, respectively. The locations of the two pairs are close in the N-direction and separated in the L-direction by about 150–200 km, (~3–4d i for n 0 = 25 cm−3). The estimated width of the U iL jets in the N-direction is about 100–150 km (a few d i). The M–N map indicates that this jet structure in the L–N plane extends in the M-direction over more than 200 km (~4d i). In addition, as shown in Fig. 4b, the density dips of the upstream pair (MMS3 and 4) are ~1.5 times deeper and ~2 times shorter than the downstream ones (MMS1 and 2). These features are in quantitative agreement with those seen in the simulation shown in Figs. 3 and 4a especially for the size of the jet (more than 4d i in the L- and M-directions with a few d i width in the N-direction) and for the depth and width of the density dips between the two locations separated by about 4d i in the L-direction.

Evolution of plasma mixing within the turbulent vortex layer

These quantitative consistencies between the simulation and observation strongly suggest that the formation of the ion-scale VIR jets and the associated high-density layers on the low-density (magnetospheric) side most likely occurred in this MMS event. Since these density structures tend to rapidly decay within Δtα < 1 in the simulation (Fig. 1b), the consistencies naturally suggest that the KHI at the MMS location was in the early non-linear phase (tα ~ 5) as shown in the second panel in Fig. 2e. Based on this evidence, we can estimate the mass transfer across the magnetopause for this event. As seen in Fig. 5a, the mixing region rapidly expands after the onset of the VIR. Assuming that the KH vortex propagates along the magnetopause at the phase speed of the KHI and the background shearing flow is constant (i.e., not globally changed), the simulation time can be converted to the propagation distance from the onset location13. This propagation distance predicts the formation of the mixing layer with thickness 1.5R E at 0 < X GSM < 5R E (Fig. 5d). The mass flux and particle entry rate into the mixing region and the corresponding diffusion coefficient start to increase at around the MMS location (Fig. 5b, c), due to the evolution of the VIR. The entry rate of the solar wind (magentosheath) particles reaches R entry ~ N KH × 1.0 × 1026 s−1, where N KH is the number of KH vortices simultaneously generated along the magnetopause. This value is comparable or larger than the rate resulting from reconnection for a large magnetic shear (R entry ~1024–1027 s−1), which was estimated from in situ observations31, 32. The diffusion coefficient reaches D ~ 0.7–1.0 × 1011 m2 s−1 for the magnetosheath particles and D ~ 0.2–0.5 × 1011 m2 s−1 for the magnetospheric particles. The theoretically required diffusion coefficient33 for populating the mixing layer, which is frequently observed along the low-latitude magnetopause is D ~ 109 m2 s−1. In addition, past simulation and observational studies of the KHI excited at the magnetopause8, 10,11,12,13, 34 predicted similar values in the range about D ~ 109–1010 m2 s−1. However, the values from the present simulation (D ~ 1011 m2 s−1) are almost one order higher than these past predictions for the KHI (Fig. 5c). As illustrated in Fig. 5d, this may contribute to the formation of a thicker mixing layer along the more distant magnetopause than previous predictions8, 13, 16.

Time evolution of the plasma mixing. a–c Time evolution of a the locations in y of the mixing surfaces (defined by \(\left| {F_{\mathrm{e}}} \right|\) = 0.99 as defined in ref. 13) averaged along the x and z-direction with standard deviations, b the mass flux \(j_m = \left( {{\mathrm{d\Sigma }}m{\mathrm{/d}}t} \right){\mathrm{/}}\left( {L_xL_z} \right)\) computed from the time variation of the integrated mass entering the mixing region across the mixing surfaces, and the corresponding entry rate per one wavelength of the KH vortex R entry = j m m e λ KH 2, of the particles (electrons) originally located in the magnetosheath (red) and the magnetosphere (blue), and c the diffusion coefficient D estimated from the Fick’s law j m/D = d(m e n e)/dx ~ m e n 0/L mix where L mix is the averaged thickness in y of the mixing region. The dashed line in a is of the smaller vortex case shown in ref. 13. The entry rate in b is obtained by assuming that the thickness of the KHI-active region in the Z GSM direction is ~λ KH. d MMS trajectory in the X GSM–Y GSM plane during 1000–1200 UT on 8 September 2015 with the model magnetopause defined in ref. 51. The green regions in d are the locations of the mixing surfaces shown in a projected onto the modeled magnetopause. The entry rate in the s−1 unit in b, the diffusion coefficient in the m2 s−1 unit in c and the special scale for the projection in d are obtained by using the typical parameters during the event; n 0 = 25 cm−3, V 0 = 355 km s−1, and λ KH = V KHΔt KH ~ 15,000 km

Discussion

The previous smaller-scale kinetic simulations of VIR22, which also showed nearly one order smaller D (~ 1010 m2 s−1 as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1b), predicted that the typical distance between well-developed primary X-lines (i.e., the typical primary flux rope size) scales with λ KH and is of the order of ~0.1λ KH (cf., Supplementary Fig. 1). This is consistent with the distance (~8d i = 0.08λ KH) of the present larger-scale simulation (Fig. 3b). Based on this scaling, assuming that ion-scale reconnection jets are strongly suppressed when the available room on each side of X-line is less than a few d i, the condition for the strong growth of ion-scale jets can roughly be predicted as

This prediction naturally explains why the ion-scale jets could not be seen in the previous smaller-scale simulations13, 22 (λ KH = 15–30d i) as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1b, but can be observed in the present simulation (λ KH = 100d i) as well as the MMS event analyzed in this paper (λ KH ~ 300d i 25).

In addition, the past 3D kinetic simulations of guide-field reconnection30, 35 suggested that the structure of an ion-scale primary reconnection layer is strongly disturbed by the turbulent development of the secondary 3D tearing mode within Δt ~ 30–50 Ωi −1 where Ωi −1 is the ion gyrofrequency based on B 0. This implies that the necessary condition for the development of primary flux rope structures from VIR decay during the early non-linear phase (i.e., the time between tα ~ 4.5–6) is roughly

This estimate naturally explains why the primary jet structures (and the related primary flux rope structures) in the present simulation (α −1 ~ 90 Ω i −1) decay within the early non-linear phase, but the primary ropes in the previous smaller-scale simulations13, 22 (α −1 ~ 11–21 Ω i −1) can survive until the late non-linear phase (cf., Supplementary Fig. 1b). Since α −1 ~ 300 Ω i −1 in this particular MMS event, the conditions satisfy the above decay constraint for the primary structures. Note that the initial source of both the primary jet and secondary turbulence is electron-scale tearing modes excited within thin electron-scale current layers21, 22, 30, 35, 36. Past kinetic studies suggested that electron-scale tearing modes (flux ropes) rapidly merge into ion-scale flux ropes within a short time (Δt < a few Ωi −1)35, 37. Thus the formation and decay processes of the ion-scale jets are not significantly affected by the initial electron-scale modes, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2c.

In summary, as predicted in Eqs. (2) and (3), the formation and decay of ion-scale VIR jet structures can occur in the early non-linear growth phase of the KHI when the spatial and growth time scales of the KHI are much larger than the ion scales (\(\lambda _{{\mathrm{KH}}} \gg d_i\), \({\mathrm{\alpha }}^{ - 1} \gg {\mathrm{\Omega }}_i^{ - 1}\)). These conditions are easily satisfied for typical encounters of KH waves in the Earth’s magnetopause including the MMS event analyzed in this paper. While there are a number of simulation studies of the KHI using single and multi-fluid8, 17,18,19, 38, 39 and hybrid kinetic-ion/electron-fluid12, 40 simulations, fully kinetic 3D simulations are required to accurately describe the physics of VIR21, since this approach permits a realistic spectrum of secondary tearing modes to develop22 and modify the plasma transport30. However, resolving the broad range of scales in fully kinetic simulations is very challenging, even for the newest generation of petascale computers. The fully kinetic 3D results presented in this letter represent the first such example, allowing us to quantitatively investigate the ion-scale VIR physics for the first time. The resulting mass transfer rate is nearly one order of magnitude larger than previous small-scale 3D kinetic simulations13, 22 (cf., Supplementary Fig. 2b). In addition, the rapid variations of plasma moments produced by the ion-scale jets seen in Fig. 4b can only be resolved using the new high-resolution MMS measurements41. Taken together, the present simulation and observational results suggest that the mass transfer from the VIR may be significantly stronger than previously thought. This finding is crucial for understanding how the solar wind enters the Earth’s magnetosphere, but may also be important for other planetary magnetospheres, or the thin boundary layer at the outer heliosphere. Finally, these simulations may be important for understanding the general problem of dissipation and transport in turbulent kinetic plasmas42, and in the future it will be useful to compare with other turbulent processes with similar power law indices (~k −8/3 to k −5/3), such as magnetic reconnection in the magnetotail43,44,45 and turbulence in the magnetosheath46,47,48 and solar wind49, 50.

Methods

Simulation settings

The simulation was performed on the Titan machine at the Oak Ridge Leadership Computing Facility, using the high-performance 3D fully kinetic particle-in-cell code VPIC23, 24, which solves the relativistic Vlasov–Maxwell system of equations. The initial density, magnetic field, and ion bulk velocities between the two regions across the boundary are set up by referring to the values obtained from the MMS observations in the magnetosphere and the magnetosheath before and after the interval 1010–1120 UT on 8 September 2015 during which the quasi-periodic KH waves were observed25,26,27,28,29. Denoting the higher and lower density sides as 1 and 2, we first chose the density (n 1, n 2), the magnetic field (B 1, B 2), and the bulk velocities (U 1, U 2), in coordinates (x′, y′, z′) where x′ is the direction of the shearing flow whose amplitude is V 0, y′ is the boundary normal using the magnetopause model51, and z′ is obtained from \({\bf{e}}_{\mathrm{x}}^\prime\) × \({\bf{e}}_{\mathrm{y}}^\prime\). Then, the values were converted to coordinates (x, y = y′, z) along the k-vector of the fastest growing mode of the KHI52, in which the x-axis is rotated by −8.3 degrees from the x′-direction in the x–z plane. The rotation angle is obtained from Eq. (1) by substituting the above values in regions 1 and 2. The obtained set of values used in the simulation are n 2/n 1 = 0.3, (B x1 , B y1 , B z1 ) = (−0.1B 0, 0, B 0), (B x2 , B y2 , B z2 ) = (0.2B 0, 0, B 0), (U x1 , U y1 , U z1 ) = (V 0cos(8.3°), 0, V 0sin(8.3°)), and (U x2 , U y2 , U z2 ) = (0, 0, 0), where n 1 = n 0 = 25 cm−3, B 0 = 74 nT, |V 0| = 355 km s−1 = 1.1 V A based on n 0 and B 0. The y-component of the magnetic field and velocities were neglected, since these are smaller than the x and z components. The ion density, the magnetic field, and the ion and electron bulk velocities are prescribed by connecting the above values using the tanh(y/L) function13, where L = 6.67d i is the initial thickness of the shear layer. The electron temperature is set to be uniform, while the ion temperature is set to satisfy the pressure balance, where the ion-to-electron temperature ratios in region 1 and 2 are set to be T i1/T e0 = 3.0 and T i2/T e0 = 11.53, respectively. The total plasma β in region 1 and 2 are 0.50 and 0.53, respectively. The additional electron and ion flows are added to satisfy the shifted Harris type current sheet of the B x component. The electric field is set to satisfy E = −U e × B, and the electron density is set to be slightly higher than the ion density in the shear layer to satisfy the Gauss’s law53. The ion-to-electron mass ratio m i/m e = 25, and the ratio between the electron plasma frequency and the gyrofrequency based on n 0 and B 0 ω pe/Ωe = 1.0. The system size is L x × L y × L z = 100d i × 150d i × 50d i = 2048 × 3072 × 1024 cells with a total of 1.3 × 1012 superparticles. The system length L x = 15L corresponds to the wavelength of the fastest growing KH mode6, which is a few times smaller than the observed wavelength. The system is periodic in the x- and z-directions, and the y-boundaries are modeled as perfect conductors for the fields and reflecting for the particles.

MMS observations and local coordinate systems

The in situ observation data shown in Fig. 4b were obtained from the MMS spacecraft during the same interval (around 10:26:30 UT on 8 September 2015) as shown in Fig. 2 in ref. 27. Although ref. 27 only showed the data from MMS1, this study required a multi-spacecraft analysis of the data from all four MMS spacecraft. The local coordinates (LMN) in Fig. 4b are also obtained in the same manner as Fig. 2 in ref. 27, where the normal direction N (=(0.95, 0.08, −0.31) in GSM) is obtained by the timing analysis of the magnetic field data, the M (=(0.21, 0.58, 0.79) in GSM) direction is defined by the cross product between N and the maximum variance direction of the magnetic field54 across the boundary and L = M × N (=(−0.25, 0.81, −0.54) in GSM) completes the system. See ref. 27 for further details for the MMS observation methods in this event.

For the simulation, the local coordinates (in the zoomed-in-views of the VIR regions shown in Figs. 1b and 3 and the virtual observation plot in Fig. 4a) are obtained in the same procedure as the observation, except that N is obtained as the cross product normal54 N = (B a × B b)/|B a × B b| where B a and B b are the magnetic field shortly after and before the boundary crossing, respectively. The L′- and N′-directions marked in Figs. 1b and 3b show the L- and N-directions, respectively, projected in the x–y plane.

Data availability

The simulation data that support the findings of this study are available via the Oak Ridge Leadership Computing Facility (OLCF) repository (https://doi.ccs.ornl.gov/ui/doi/46). The observational portion of this research uses the data from the MMS spacecraft, which are publically available via NASA resources and the Science Data Center at CU/LASP (https://lasp.colorado.edu/mms/sdc/public/).

References

Dungey, J. Interplanetary magnetic field and the auroral zones. Phys. Rev. Lett. 6, 47–48 (1961).

Cowley, S. W. H. Plasma populations in a simple open model magnetosphere. Space Sci. Rev. 26, 217–275 (1980).

Shibata, K. Evidence of magnetic reconnection in solar flares and a unified model of flares. Astrophys. Space Sci. 264, 129–144 (1999).

Pope, E. C. D. On the exclusion of intracluster plasma from active galactic nuclei-blown bubbles. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 404, 451–457 (2010).

Sckopke, N. G. et al. Structure of the low-latitude boundary layer. J. Geophys. Res. 86, 2099–2110 (1981).

Miura, A. & Pritchett, P. L. Nonlocal stability analysis of the MHD Kelvin-Helmholtz instability in a compressible plasma. J. Geophys. Res. 87, 7431–7444 (1982).

Kavosi, S. & Raeder, J. Ubiquity of Kelvin-Helmholtz waves at Earth’s magnetopause. Nat. Commun. 6, 7019 (2015).

Nykyri, K. & Otto, A. Plasma transport at the magnetospheric boundary due to reconnection in Kelvin-Helmholtz vortices. Geophys. Res. Lett. 28, 3565–3568 (2001).

Hasegawa, H. et al. Transport of solar wind into Earth’s magnetosphere through rolled-up Kelvin-Helmholtz vortices. Nature 430, 755–758 (2004).

Matsumoto, Y. & Hoshino, M. Turbulent mixing and transport of collisionless plasmas across a stratified velocity shear layer. J. Geophys. Res. 111, A05213 (2006).

Chaston, C. C. et al. Mode conversion and anomalous transport in Kelvin-Helmholtz vortices and kinetic Alfvén waves at the Earth’s magnetopause. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 175004 (2007).

Cowee, M. M., Winske, D. & Gary, S. P. Hybrid simulations of plasma transport by Kelvin‐Helmholtz instability at the magnetopause: density variations and magnetic shear. J. Geophys. Res. 115, A06214 (2010).

Nakamura, T. K. M. & Daughton, W. Turbulent plasma transport across the Earth’s low-latitude boundary layer. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 8704–8712 (2014).

Ma, X., Otto, A. & Delamere, P. A. Interaction of magnetic reconnection and Kelvin-Helmholtz modes for large magnetic shear: 1. Kelvin-Helmholtz trigger. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 119, 781–797 (2014).

Chandrasekhar, S. Hydrodynamic and Hydromagnetic Stability 481 (Dover, New York, 1961).

Fairfield, D. H. et al. Geotail observations of Kelvin-Helmholtz instability at the equatorial magnetotail boundary for parallel northward fields. J. Geophys. Res. 105, 2115921173 (2000).

Nakamura, T. K. M., Fujimoto, M. & Otto, A. Magnetic reconnection induced by weak Kelvin-Helmholtz instability and the formation of the low-latitude boundary layer. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L14106 (2006).

Nakamura, T. K. M., Fujimoto, M. & Otto, A. Structure of an MHD-scale Kelvin-Helmholtz vortex: two-dimensional two-fluid simulations including finite electron inertial effects. J. Geophys. Res. 113, A09204 (2008).

Chen, Q., Otto, A. & Lee, L. C. Tearing instability, Kelvin-Helmholtz instability, and magnetic reconnection. J. Geophys. Res. 102, 151–161 (1997).

Nykyri, K. et al. Cluster observations of reconnection due to the Kelvin-Helmholtz instability at the dawnside magnetospheric flank. Ann. Geophys. 24, 2619–2643 (2006).

Nakamura, T. K. M., Hasegawa, H., Shinohara, I. & Fujimoto, M. Evolution of an MHD-scale Kelvin-Helmholtz vortex accompanied by magnetic reconnection: two-dimensional particle simulations. J. Geophys. Res. 116, A03227 (2011).

Nakamura, T. K. M., Daughton, W., Karimabadi, H. & Eriksson, S. Three-dimensional dynamics of vortex-induced reconnection and comparison with THEMIS observations. J. Geophys. Res. 118, 5742–5757 (2013).

Bowers, K. J., Albright, B. J., Yin, L., Bergen, B. & Kwan, T. J. T. Ultrahigh performance three-dimensional electromagnetic relativistic kinetic plasma simulation. Phys. Plasmas 15, 055703 (2008).

Bowers, K. et al. Advances in petascale kinetic simulations with VPIC and Roadrunner. J. Phys. Conf. Series 180, 012055 (2009).

Eriksson, S. et al. Magnetospheric multiscale observations of magnetic reconnection associated with Kelvin-Helmholtz waves. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 5606–5615 (2016).

Eriksson, S. et al. Magnetospheric multiscale observations of the electron diffusion region of large guide field magnetic reconnection. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 015001 (2016).

Li, W. et al. Kinetic evidence of magnetic reconnection due to Kelvin-Helmholtz waves. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 5635–5643 (2016).

Vernisse, Y. et al. Signatures of complex magnetic topologies from multiple reconnection sites induced by Kelvin-Helmholtz instability. J. Geophys. Res. 121, 9926–9939 (2016).

Stawarz, J. E. et al. Observations of turbulence in a Kelvin-Helmholtz event on 8 September 2015 by the magnetospheric multiscale mission. J. Geophys. Res. 121, 11021–11034 (2016).

Daughton, W., Nakamura, T. K. M., Karimabadi, H., Roytershteyn, V. & Loring, B. Computing the reconnection rate in turbulent kinetic layers by using electron mixing to identify topology. Phys. Plasmas 21, 052307 (2014).

Hasegawa, H. Structure and dynamics of the magnetopause and its boundary layers. Monogr. Environ. Earth Planets 1, 71–119 (2012).

Shi, Q. Q. et al. Solar wind entry into the high-latitude terrestrial magnetosphere during geomagnetically quiet times. Nat. Commun. 4, 1466 (2013).

Sonnerup, B. Theory of the low‐latitude boundary layer. J. Geophys. Res. 85, 2017–2026 (1980).

Wing, S., Johnson, J. R. & Fujimoto, M. Timescale for the formation of the cold-dense plasma sheet: A case study. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L23106 (2006).

Nakamura, T. K. M., Nakamura, R., Narita, Y., Baumjohann, W. & Daughton, W. Multi-scale structures of turbulent magnetic reconnection. Phys. Plasmas 23, 052116 (2016).

Daughton, W. et al. Role of electron physics in the development of turbulent magnetic reconnection in collisionless plasmas. Nat. Phys. 7, 539–542 (2011).

Karimabadi, H., Dorelli, J., Roytershteyn, V., Daughton, W. & Chacón, L. Flux pileup in collisionless magnetic reconnection: bursty interaction of large flux ropes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 025002 (2011).

Knoll, D. A. & Chacon, L. Magnetic reconnection in the twodimensional Kelvin-Helmholtz instability. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 215003 (2002).

Nykyri, K. & Otto, A. Influence of the Hall term on KH instability and reconnection inside KH vortices. Ann. Geophys. 22, 935–949 (2004).

Delamere, P. A., Wilson, R. J. & Masters, A. Kelvin‐Helmholtz instability at Saturn’s magnetopause: hybrid simulations. J. Geophys. Res. 116, A10222 (2011).

Burch, J. L. et al. Electron-scale measurements of magnetic reconnection in space. Science 352, aaf2939 (2016).

Howes, G. G. A prospectus on kinetic heliophysics. Phys. Plasmas 24, 055907 (2017).

Eastwood, J. P., Phan, T. D., Bale, S. D. & Tjulin, A. Observations of turbulence generated by magnetic reconnection. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 035001 (2009).

Huang, S. Y. et al. Observations of turbulence within reconnection jet in the presence of guide field. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L11104 (2012).

Osman, K. T. et al. Multi-spacecraft measurement of turbulence within a magnetic reconnection jet. Astrophys. J. Lett. 815, L24 (2015).

Sahraoui, F. et al. Anisotropic Turbulent Spectra in the Terrestrial Magnetosheath as Seen by the Cluster Spacecraft. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 075002 (2006).

Breuillard, H., Yordanova, E., Vaivads, A. & Alexandrova, O. The effects of kinetic instabilities on small-scale turbulence in Earth’s magnetosheath. Astrophys. J. 829, 54 (2013).

Huang, S. Y. et al. Magnetospheric multiscale observations of electron vortex magnetic hole in the turbulent magnetosheath plasma. Astrophys. J. Lett. 836, L27 (2017).

Alexandrova, O., Lacombe, C., Mangeney, A., Grappin, R. & Maksimovic, M. Solar wind turbulent spectrum at plasma kinetic scales. Astrophys. J. 760, 121 (2012).

Sahraoui, F. et al. Scaling of the electron dissipation range of solar wind turbulence. Astrophys. J. 777, 15 (2013).

Shue, J.-H. et al. Magnetopause location under extreme solar wind conditions. J. Geophys. Res. 103, 17691–17700 (1998).

Adamson, E., Nykyri, K. & Otto, A. The Kelvin-Helmholtz instability under Parker-spiral interplanetary magnetic field conditions at the magnetospheric flanks. Adv. Space Res. 58, 218–230 (2016).

Pritchett, P. L. & Coroniti, F. V. The collisionless macroscopic Kelvin-Helmholtz instability 1: transverse electrostatic mode. J. Geophys. Res. 89, 168–178 (1984).

Sonnerup, B. U. Ö. & Scheible, M. in Analysis Methods for Multi-Spacecraft Data, ISSI Sci. Rep. SR-001 (eds Paschmann, G. & Daly, P. W.) 185–220 (Eur. Space Agency Publ. Div, Noordwijk, 1998).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge support from the Austrian Research Fund (FWF): I2016-N20. The simulation part of this research used resources of the Oak Ridge Leadership Computing Facility, which is a DOE Office of Science User Facility supported under Contract DE-AC05-00OR22725. The simulation data were also analyzed with resources at the Space Research Institute of Austrian Academy of Sciences. Contributions from W.D. were supported by NASA grant NNH13AV26I. Contributions from S. E. were supported by NASA MMS-Phase E support to CU/LASP and NASA grants NNX08AO84G and NNH13AV26I. We thank T. Nagai, Y. Narita, S. Zenitani K. Genestreti, and M.H. Spencer for their fruitful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.K.M.N. carried out the kinetic simulation and the multipoint data analysis, and wrote the paper. T.K.M.N., H.H. and W.D. contributed to the analysis of the simulation data. H.H., S.E. W.L. and R.N. contributed to handling the observation data. S.E. contributed to set up the simulation. W.D. supported the simulation performed on Titan, and contributed to writing and editing the manuscript. All of the authors discussed the results and commented on the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nakamura, T.K.M., Hasegawa, H., Daughton, W. et al. Turbulent mass transfer caused by vortex induced reconnection in collisionless magnetospheric plasmas. Nat Commun 8, 1582 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-01579-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-01579-0

This article is cited by

-

Alfvén resonance on Kelvin-Helmholtz vortices at the Earth’s magnetopause

Astrophysics and Space Science (2024)

-

Magnetic Reconnection at Planetary Bodies and Astrospheres

Space Science Reviews (2024)

-

Ion and electron acoustic bursts during anti-parallel magnetic reconnection driven by lasers

Nature Physics (2023)

-

Cross-Scale Processes of Magnetic Reconnection

Space Science Reviews (2023)

-

Magnetic reconnection in the era of exascale computing and multiscale experiments

Nature Reviews Physics (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.