Abstract

CD103+CD11b+ dendritic cells (DCs) are unique to the intestine, but the factors governing their differentiation are unclear. Here we show that transforming growth factor receptor 1 (TGFβR1) has an indispensable, cell intrinsic role in the development of these cells. Deletion of Tgfbr1 results in markedly fewer intestinal CD103+CD11b+ DCs and a reciprocal increase in the CD103−CD11b+ dendritic cell subset. Transcriptional profiling identifies markers that define the CD103+CD11b+ DC lineage, including CD101, TREM1 and Siglec-F, and shows that the absence of CD103+CD11b+ DCs in CD11c-Cre.Tgfbr1 fl/fl mice reflects defective differentiation from CD103−CD11b+ intermediaries, rather than an isolated loss of CD103 expression. The defect in CD103+CD11b+ DCs is accompanied by reduced generation of antigen-specific, inducible FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in vitro and in vivo, and by reduced numbers of endogenous Th17 cells in the intestinal mucosa. Thus, TGFβR1-mediated signalling may explain the tissue-specific development of these unique DCs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dendritic cells (DCs) are central to the regulation of immune function in the intestine. They control whether tolerance or active immunity is induced by different kinds of antigens, specify the nature of responses that occur and imprint primed T and B cells with the selective ability to return to the intestinal mucosa1. Although most of these events take place when DCs encounter naive lymphocytes in the draining mesenteric and colonic lymph nodes2,3,4, the relevant DCs are derived from the Peyer’s patches (PPs) or lamina propria (LP) of the mucosa itself, where they capture antigen before emigrating to lymph nodes in afferent lymphatics5. Therefore, exploring the biology of mucosal DCs is essential to understand the cellular basis of immune responses in the intestine.

Work by ourselves and others has revealed heterogeneity among DCs in the mouse intestine, with four major subsets based on the expression of CD103 and CD11b6,7,8. These cells include a prominent population of CD103+CD11b+ DCs, a subset unique to the intestine and its draining lymphoid tissues5. Intestinal CD103+CD11b+ DCs are functionally and ontogenically distinct from the Batf3/IRF8-dependent, XCR1+CD103+CD11b− DCs with cross-presenting activity in the gut and elsewhere9,10,11, commonly referred to as conventional DC subset 1 (cDC1)12. However, the development of CD103+CD11b+ DCs is yet to be dissected fully. Several factors have been reported to be important for the homeostasis of these cells including colony-stimulating factor 2 (CSF2)13, Notch-214, IRF48, 15, retinoic acid16 and signal regulatory protein α (SIRPα)17. However, whether these factors link to a common developmental pathway and why this unusual population is restricted to the intestine are unclear.

Transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) is abundant in the intestine and induces the expression of CD103 on intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes and regulatory T (Treg) cells with effector function18, 19. TGFβ is also reported to influence the development and/or homeostasis of several myeloid cell populations, including Langerhans cells and microglia20,21,22,23. However, the role of TGFβ-mediated signalling in DC development in the intestinal mucosa has not been addressed directly. Using refined approaches we have developed to identify DC subsets and other CD11c+ cells in the intestine6, 24, we show here that mice lacking the TGFβR1 on CD11c+ cells have a selective and cell-intrinsic defect in CD103+CD11b+ DCs in the intestine. By developing a panel of markers that defines this lineage, we show that the loss of CD103+CD11b+ DCs reflects a defect in differentiation from a CD103−CD11b+ intermediate, rather than just the absence of CD103 expression. The lack of TGFβR1-dependent CD103+CD11b+ DCs is accompanied by defective generation of antigen-specific, inducible FoxP3+ Treg cells in vitro and in vivo, and by reduced numbers of Th17 cells in the intestinal mucosa. Thus, TGFβ-mediated signalling is indispensable for the phenotypic and functional imprinting of LP CD103+CD11b+ DCs.

Results

T-cell-dependent inflammation in CD11c-Cre.Tgfbr1 fl/fl mice

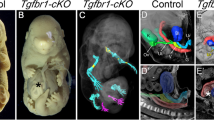

To explore the role of TGFβ in intestinal DC development, we crossed Tgfbr1 fl/fl mice with Itgax-Cre mice, which constitutively express Cre recombinase under control of the CD11c promoter25 (referred to here as CD11c-Cre). Although CD11c-Cre.Tgfbr1 fl/fl mice (Cre+) and non-transgenic Tgfbr1 fl/fl littermates (Cre−) were born at Mendelian frequencies, Cre+ mice developed a wasting disease and died before 20 weeks of age (Figs. 1a, b and Supplementary Fig. 1a). This was associated with activation of splenic T cells, inflammation of the stomach, colon, liver and lungs, where there were leukocytic infiltrates and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Supplementary Fig. 1b–f). These findings are consistent with a previous report of wasting disease in CD11c-Cre-Tgfbr2 fl/fl mice26 and highlight the need for TGFβ signalling in control of inflammatory pathology.

T-cell-dependent inflammatory disease in CD11c-Cre.Tgfbr1 fl/fl mice. a Body weights of CD11c-Cre.Tgfbr1 fl/fl (Cre+) mice and Tgfbr1 fl/fl (Cre−) mice littermate controls presented as a percentage of original bodyweight at 9 weeks of age. The results are the means ± 1 SD of five (Cre+) or six (Cre−) mice per group and are representative of two experiments (**p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001—Student’s t-test followed by Holm–Sidak correction). († indicates the loss of animal from group). b Representative colonic pathology as assessed by epithelial cell turnover (Ki67 staining—left panels) and goblet cell density (PAS staining—right panels) in Cre− (upper panels) and Cre+ mice (lower panels). Arrows indicate loss of goblet cells. Scale bar, 1 mm. c Experimental scheme for the transfer of splenic T cells from Cre− or Cre+ mice into congenic WT recipients. d Survival of WT recipients given T cells from Cre− ro Cre+ mice. Data are pooled from two experiments with a total of seven (Cre−) or eight (Cre+) mice per group. e Frequency of CD45.2+ donor T cells among total blood T cells (left) and the frequency of donor cells within the CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell compartments (centre and right) at 1, 2 and 3 weeks post transfer in the mice from c, d above. Data are from one of two independent experiments each with 3 (Cre+) or 4 (Cre−) mice per group. f Expression of mRNA transcripts for Gzmb, Ifng, Tnfa and Nos2 in the stomach of recipients of splenic T cells from Cre− or Cre+ mice in d above. In e, f, bars represent the mean + SD of three mice per group and mRNA expression is relative to expression of Gapdh. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 and ****p < 0.0005 determined by two-tailed Student’s t-test

As some T cells may exhibit functional Cre activity in CD11c-Cre mice25 and disruption of TGFβ signalling in T cells is known to provoke a lethal inflammatory disease27, 28, we examined whether lack of TGFβR1 signalling in T cells might contribute to the inflammatory disease in CD11c-Cre.Tgfbr1 fl/fl mice. Analysis of T cells purified from the spleen of these mice demonstrated clear Cre-mediated deletion of genomic Tgfbr1 (Supplementary Fig. 1g), whereas ~ 8% of circulating T cells and ~ 12% of CD3+ small intestinal LP (SILP) T cells were labelled in CD11c-Cre.Rosa26-LSL-YFP mice (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b). Thus, Cre-mediated recombination occurs in T cells in the CD11c-Cre strain. Furthermore, CD3+ T cells from Cre+ mice transferred the lethal wasting disease into congenic wild-type (WT) recipients, with expansion and activation of donor CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, gastritis and expression of messenger RNA for proinflammatory mediators in the stomach (Figs. 1c–f). In contrast, T cells from Cre− littermates showed only limited and transient expansion in recipient mice and these animals remained healthy. Of note, a significant fraction of T cells transferred from Cre+ donors had lost the Tgfbr1 gene (Supplementary Fig. 1g) and crossing the CD11c-Cre.Tgfbr1 fl/fl mice on to the Rag1 −/− background prevented wasting disease, confirming that the pathology involved deletion of the TGFβR1 in T cells.

CD11c+ myeloid cells prevent T-cell-mediated colitis

Although these findings implied that TGFβR1 signalling in T cells normally prevents inflammatory disease, previous work suggested that the wasting disease seen in CD11c-Cre-Tgfbr2 fl/fl mice was dependent on DCs26. To investigate whether this might also contribute to the development of inflammatory disease in CD11c-Cre.Tgfbr1 fl/fl mice, we transferred total T cells from WT (CD45.1) donors into Rag1 −/− CD11c-Cre.Tgfbr1 fl/fl mice (hereafter referred to as Rag1 −/− Cre+) or Rag1 −/− Tgfbr1 fl/fl mice (hereafter referred to as Rag1 −/− Cre−) (Fig. 2a). Strikingly, following T-cell transfer, Rag1 −/−Cre+ recipient mice showed marked growth retardation compared with Rag1 −/−Cre− control mice (Fig. 2b), together with severe colitis associated with accumulation of CD4+ T cells and expression of mRNA for tumour necrosis factor-α, inducible nitric oxide synthase, interferon (IFN)-γ and interleukin (IL)-17A (Figs. 2b–f). Thus, the absence of TGFβR1-mediated signalling in CD11c-expressing cells other than T cells also contributes to T-cell-driven colitis in CD11c-Cre.Tgfbr1 fl/fl mice.

TGFβR1 signalling in CD11c+ myeloid cells prevents T-cell-mediated colitis. a Experimental scheme for induction of colitis by transfer of CD45.1+ WT spleen T cells mice into Rag1 −/− Tgfbr1 fl/fl (Rag1 −/−Cre−) or Rag1 −/− CD11c-Cre.Tgfbr1 fl/fl (Rag1 −/−Cre+) recipients. b Body weights following adoptive transfer of WT T cells shown as percentage of starting weight. The results are the means ± 1 SD of four mice per group from one of two independent experiments. c Representative colonic pathology as assessed by haematoxylin and eosin staining, Ki67 staining of dividing epithelial cells, PAS+ goblet cells and CD3+ T cells at 10–17 weeks post-transfer. Scale bar, 500 μm. d Histological scoring of proximal and distal colon. Data are pooled from four independent experiments with a total of six (Rag1 −/−Cre−) or nine (Rag1 −/−Cre+) recipients per group. *p < 0.05 determined by Mann–Whitney test. e CD4 and CD8 expression in colon at 10–17 weeks post transfer. Scale bar, 500 μm. f Expression of mRNA transcripts for Tnfa, Ifng, Il17a, Ccl5 and Nos2 in the colon. Error bars represent the mean + 1 SD of two (Rag1 −/−Cre−) or five (Rag1 −/−Cre+) mice per group and mRNA expression is relative to expression of Abl. Data are from one of three independent experiments performed. *p < 0.05 and ***p < 0.001 determined by two-tailed Student’s t-test

TGFβR1 signalling controls intestinal DC homeostasis

We reasoned that this inflammation may reflect a role for the mononuclear phagocytes that contribute to the generation and/or differentiation of pathogenic T cells in the intestine and thus we explored the populations of DCs and macrophages present in the mucosa of Rag1 −/−Cre+ mice. As has been found in immunocompetent mice6, 7, 29, the SILP of Rag1 −/−Cre− mice contained four subsets of bona fide CD11c+MHCII+CD64− DCs, distinguished by their differential expression of CD103 and CD11b (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 2a). The absolute numbers and proportions of DCs co-expressing CD11b and CD103 were severely reduced in Rag1 −/−Cre+ mice compared with Rag1 −/−Cre− or Cre+ Tgfbr1 fl/+ littermate controls, with parallel increases in the CD11b+CD103− DC subset (Figs. 3a, b and Supplementary Fig. 2b). CD103+CD11b− and CD103−CD11b− DCs were present at comparable frequencies and numbers in Rag1 −/−Cre+ and Cre− mice, although as with the remaining CD103+CD11b+ DCs, CD103+CD11b− DCs showed reduced levels of CD103 expression in Cre+ mice (Figs. 3a, b). As the small CD103−CD11b− subset is variable in size, is phenotypically heterogeneous and may derive from isolated lymphoid follicles7, it has not been ascribed specific functions in the LP and it is not explored further here. Importantly, despite expressing high levels of CD11c and exhibiting Cre activity (Supplementary Fig. 3a), the absolute numbers of CD64+ mϕ were equivalent in the small intestine of Rag1 −/−Cre+ and Rag1 −/−Cre− mice (Fig. 3c). There was a similar reduction in CD103+CD11b+ DCs in the colonic mucosa of Rag1 −/−Cre+ mice compared with Rag1 −/−Cre− littermate controls, together with an increased proportion of the CD103−CD11b+ subset. Unlike the small intestine, the frequencies of CD103+CD11b− DCs were also reduced in the colon of Rag1 −/−Cre+ mice (Fig. 3d). Notably, there were no differences in the populations of CD11b+ and CD11b− DCs in the spleen of Rag1 −/−Cre+ and Rag1 −/−Cre− mice (Fig. 3e). We were unable to obtain sufficient cells from the hypotrophic lymph nodes of Rag1 −/− mice to assess DC populations in these tissues.

TGFβR1 signalling controls dendritic cell homeostasis in the intestine. a Expression of CD103 and CD11b by live CD45+CD11c+MHCII+CD64− DC (left) and relative frequencies of DC subsets (right) in the SILP of Rag1 −/− Tgfbr1 fl/fl mice (Rag1 −/−Cre−) or Rag1 −/− CD11c-Cre.Tgfbr1 fl/fl (Rag1 −/−Cre+) mice. b Absolute numbers of DC subsets and c CD64+Ly6C− macrophages from SI from mice in a. Data are pooled from three independent experiments with 9 (Rag1 −/−Cre−) or 10 (Rag1 −/−Cre+) mice per group. d Expression of CD103 and CD11b by live CD45+CD11c+MHCII+CD64− DC (left) and relative frequencies of DC subsets (right) in the colonic LP of Rag1 −/−Cre− or Rag1 −/−Cre+ mice. Data are pooled from two independent experiments with a total of seven mice per group. e Expression of CD103 and CD11b by live CD11c+MHCII+ DC (left) and relative frequencies of DC subsets (right) in the spleen of Rag1 −/−Cre− or Rag1 −/−Cre+ mice. Data are pooled from four independent experiments with 11 (Rag1 −/−Cre−) or 15 (Rag1 −/−Cre+) mice/group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 and ****p < 0.0001 determined by Student’s t-test followed by Holm–Sidak correction

Thus, CD11c-driven deletion of the TGFβR1 leads to a dramatic reduction in the number of CD103+CD11b+ DCs in the intestinal mucosa. To explore the underlying mechanism in more detail, we focused on the small intestine, where the relevant DC subset is most abundant.

TGFβR1-mediated control of DC homeostasis is cell intrinsic

To examine whether TGFβR1 regulation of DC homeostasis was cell intrinsic, we generated mixed bone marrow (BM) chimeric mice by reconstituting lethally irradiated (CD45.1+ × CD45.2+) WT mice with a 1:1 ratio of WT (CD45.1+) and either Rag1 −/−Cre− or Rag1 −/−Cre+ (CD45.2+) BM cells (Fig. 4a). Under these conditions, CD103+CD11b− DCs were produced equally efficiently from WT and transgenic BM regardless of whether Rag1 −/−Cre− or Rag1 −/−Cre+ BM was used to generate the chimera (Fig. 4b). In contrast, whereas CD103+CD11b+ DCs derived equally from the different BM sources in WT:Rag1 −/−Cre− chimeras, the vast majority derived from WT BM in WT:Rag1 −/−Cre+ chimeras, consistent with the reduced numbers of these cells in intact Rag1 −/−Cre+ mice (Fig. 4b). Similarly, more of the CD103−CD11b+ DC subset was derived from Rag1 −/−Cre+ BM compared with WT or Rag1 −/−Cre− BM (Fig. 4c).

TGFβR1-mediated control of DC homeostasis is cell intrinsic. a Experimental scheme for generation of mixed BM chimeric mice by reconstitution of irradiated CD45.1+ × CD45.2+ mice with a 1 : 1 mixture of BM from CD45.1+ WT and Rag1 −/−Cre− or Rag1 −/−Cre+ CD45.2+ donors. b CD45.2+ Tgfbr1 fl/fl-derived chimerism among DC subsets from WT:Rag1 −/−Cre− or WT: Rag1 −/−Cre+ mixed BM chimeras 8–12 weeks post reconstitution. Data are pooled from two independent experiments with a total of 10 mice per group and dotted line represents input chimerism. ****p < 0.0001 determined by Student’s t-test followed by Holm–Sidak correction. c, d Representative expression of CD103 and CD11b by CD45.1+ (WT-derived) or CD45.2+ (Tgfbr1 fl/fl-derived) CD11c+MHCII+CD64− cells from the SILP c or MLN d of WT:Rag1 −/−Cre− or WT:Rag1 −/−Cre+ mixed BM chimeras 8–12 weeks post reconstitution. Scatter plots show the frequency of each DC subset of the total DC pool derived from each BM source. Data are pooled from two independent experiments with 10 mice per group. Each symbol represents an individual animal and the horizontal bar represents the mean. ***p < 0.001 and ****p < 0.0001 using one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test

The presence of intact lymphoid organs in the BM chimeric mice allowed us to examine how DC populations in intestinal lymph nodes were affected by the absence of TGFβR1 signalling. As in the mucosa, Rag1 −/−Cre+ BM showed a selective defect in the ability to reconstitute CD103+CD11b+ DCs among the migratory (CD11c+MHCIIhi) population of mesenteric lymph node (MLN) DCs in WT:Rag1 −/− Cre+ chimeric mice compared with recipients of Rag1 −/−Cre− BM (Fig. 4d). Consistently, there was a concomitant overrepresentation of the CD103−CD11b+ subset of migratory MLN DCs in the recipients of Rag1 −/−Cre+ BM, whereas CD103+CD11b− MLN DCs were derived equally from Rag1 −/− Cre− or Rag1 −/− Cre+ BM.

Thus, the defect in intestinal CD103+CD11b+ DCs in Rag1 −/− Cre+ mice is due to cell intrinsic effects of TGFβR1 deficiency.

TGFβR1 controls a developmental programme in CD11b+ DCs

As TGFβ is known to control the expression of CD103 on mucosal T cells18, 30, it was possible that the apparent reduction in the CD103+CD11b+ DC compartment could reflect an isolated failure to express CD103, rather than a more general effect of TGFβR1 deficiency on intestinal DC homeostasis. To distinguish between these ideas, we sought surrogate markers that were not affected by TGFβR1 deficiency and that might allow us to identify cells within the putative CD103+CD11b+ DC lineage without using CD103 itself. As a first step in this process, we used microarray analysis to compare the transcriptomes of all four of the CD103/CD11b-defined DC subsets from WT small intestine, as this information was not available from existing databases. Hierarchical clustering analysis demonstrated that the DC subsets segregated clearly from each other and from CD64+ mϕ (Fig. 5a). As before, we excluded the small CD103−CD11b− population from this analysis and to visualise the differences between the remaining three DC populations, we plotted each gene in a graph comprising one axis per DC subset placed at a 120° angle to each other, creating a hexagonal ‘Triwise’ plot (Fig. 5b). In these hexagons, the distance of a point from the centre represents the magnitude of upregulation and genes that are upregulated in a particular subset are positioned close to the appropriate axis, whereas those that are shared by two subsets are found between the axes31, 32.

Transcriptional profiling of SILP DC reveals subset-specific markers. a Hierarchical clustering of DC subsets and CD64+MHCII+ macrophages from the SILP of WT mice based on microarray profiles. b Hexagonal ‘Triwise’ plot displaying all arrayed genes with differentially expressed genes (adj. p-value < 0.01, logFC > 1 or < 1) depicted in cyan and non-differentially expressed genes shown in brown. Each grid line represents a log2 fold change. Rose plots show the percentage of genes falling in each vectorial direction. c Triwise plot highlighting genes differentially expressed (adj. p-value < 0.01, logFC > 1 or < 1) by CD103+CD11b+ DC and CD103−CD11b+ DC and not CD103+CD11b− DC (left) and bar chart of Irf4 expression by DC subsets (right). Bars represent the mean + SEM Log2 expression values of three biological replicates. d–f Triwise plots highlighting genes differentially expressed (adj. p-value 0.01, LogFC > 1 or < 1) by CD103+CD11b− DC d, CD103+CD11b+ DC e and CD103−CD11b+ DC f (left panels) and mean + SEM Log2 expression values of Xcr1, Gp2 and Cx3cr1 by DC subsets (right panels). g Triwise plots depicting the genes that are most differentially expressed by CD103+CD11b+ and CD103−CD11b+ DC subsets compared with CD103+CD11b− DC (left); mean + SEM Log2 expression values of these genes (right)

This analysis revealed that the most differentially expressed genes segregated into two main groups, one of which was associated selectively with CD103+CD11b− DCs, whereas the other contained genes that were shared by CD103−CD11b+ and CD103+CD11b+ DCs (Figs. 5b, c). CD103+CD11b− DCs expressed a number of genes that characterise cDC1 cells in other tissues, including Xcr1, Irf8, Cd8a, Clec9a, Cadm1 and Btla (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Table 1)9, 11, 33, 34. The CD11b-expressing subsets of intestinal DC segregated relatively closely together in the hexagonal analysis and shared several genes typical of the conventional DC subset 2 (cDC2) lineage, including the transcription factors Zeb2 32 and Irf4 6, 15, 35, as well as Sirpa 12 (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Table 2). Nevertheless, a number of genes were also differentially expressed by the CD103−CD11b+ and CD103+CD11b+ subsets, indicating that CD103 is not the only marker that distinguishes these populations (Figs. 5e, f). Using the hexagonal analysis approach, 61 genes were found to be expressed at significantly higher levels by CD103−CD11b+ DCs, including Cx3cr1, Csf1r and S100a4 (Fig. 5f and Supplementary Table 3). Conversely, 31 genes were expressed at significantly higher levels by the CD103+CD11b+ DC subset, including Gp2, Cdh1 (encoding E-cadherin), Siglecv (encoding SiglecF) and Epcam (Fig. 5e and Supplementary Table 4). We attempted to exploit these markers for identifying the CD103+CD11b+ lineage by flow cytometry, but could not detect surface expression of E-cadherin or GP2 reliably. In addition, none of commercial antibodies against SiglecF or EpCAM permitted adequate discrimination of CD103+CD11b+ DCs from CD103−CD11b+ DCs, limiting their usefulness (Supplementary Fig. 4).

To overcome this issue, we extended our analysis of the microarray data to include genes that, although shared by CD103+ and CD103− CD11b-expressing DCs, were the most differentially expressed compared with the CD103+CD11b− subset (and therefore fall on the outermost ring of the hexagonal plot in the region between the CD103+CD11b+ and CD103−CD11b+ axes). This generated an additional 34 genes (Fig. 5g and Supplementary Table 6), of which 18 encoded cell surface markers (Supplementary Table 5). Commercial antibodies were available to analyse eight of these by flow cytometry (Mgl2, Siglece, Sirpa, Itgam, Cd300a, Cd209a, Trem1 and Cd101), but Cd101 and Trem1 showed clear differential expression between CD103+ and CD103− CD11b-expressing DCs at the RNA level, suggesting that they might be useful as surrogate markers (Fig. 5g). Flow cytometry showed that surface expression of TREM1 was restricted to the CD103+CD11b+ subset of SILP DCs and was present on most of these cells, as was CD101 (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Fig. 5). However, CD101 was also expressed by a fraction of CD103−CD11b+ DCs, but not by CD103+CD11b− DCs. Similar to CD103, the expression of TREM1 by CD11b+ SILP DCs was TGFβR dependent, as it was markedly reduced in Rag1 −/−Cre+ mice compared with Rag1 −/−Cre− mice (Fig. 6b). Siglec F expression by these DCs followed a similar pattern (Fig. 6b). In contrast, CD101 expression was relatively unaffected by TGFβR1 deficiency (Fig. 6b), with SILP DCs from Rag1 −/−Cre+ mice and Cre− littermates containing equivalent proportions and absolute numbers of total CD101+ DCs (Fig. 6c). Total CD101+ DCs were also derived equally from Rag1 −/−Cre− and Rag1 −/−Cre+ marrow in mixed BM chimeric mice (Fig. 6d).

CD101 and TREM1 are surrogate markers for intestinal CD103+ CD11b+ DC. a Representative expression of TREM1 and CD101 by DC subsets and CD64+MHCII+ macrophages from SILP of Rag1 −/−Cre− mice. b Representative expression of CD103, SiglecF, TREM1 and CD101 by total CD11b+ DC from the SILP of Rag1 −/−Cre− or Rag1 −/−Cre+ mice. c Representative expression of CD103 and CD101 by total CD11c+MHCII+CD64− DC (left) and the frequency and absolute numbers of CD101+ DC in the SILP of Rag1 −/−Cre− or Rag1 −/−Cre+ mice. Data are pooled from two independent experiments with seven mice per group. d Proportion of CD45.2+ Tgfbr1 fl/fl-derived cells among CD101+ DC from WT:Rag1 −/−Cre− or WT: Rag1 −/−Cre+ mixed BM chimeras 8–12 weeks post reconstitution. Data are from one of two independent experiments with five mice per group

Thus, the definitive phenotypic signature of intestinal CD103+CD11b+ DC requires the TGFβR1.

Functional effects of TGFβR1 deficiency in intestinal DCs

Depending on the experimental system, CD103+CD11b+ DCs have been implicated in the generation of both Th17 cells and FoxP3+ Treg6, 15, 35,36,37,38. Thus, we assessed whether TGFβR1-mediated deficiency in this DC lineage resulted in functional defects in T cells. To examine Treg priming in vivo, we transferred naïve ovalbumin (OVA)-specific OTII CD4+ T cells into Rag1 −/−Cre− → WT and Rag1 −/− Cre+ → WT BM chimeric mice and assessed the induction of FoxP3-expressing cells in MLN 4 days after oral administration of OVA (Fig. 7a). Notably, there were significantly fewer OVA-specific FoxP3+ Treg in the MLNs of Rag1 −/−Cre+ → WT chimeras compared with Rag1 −/−Cre− → WT chimeras (Fig. 7b). As both CD103+CD11b+ and CD103+CD11b− DCs have been shown to be able to induce Treg differentiation, we next assessed the relative capabilities of these subsets in vitro. Purified small intestinal CD101+ DCs or CD103+CD11b− DCs from Rag1 −/−Cre− or Rag1 −/−Cre+ mice were loaded with OVA peptide and co-cultured with CFSE-labelled naive OTII CD4+ T cells. Both DC subsets, irrespective of the presence or absence of TGFβR1, induced T-cell proliferation, as measured by CFSE dilution (Fig. 7f). However, whereas CD103+CD11b− DCs from Rag1 −/−Cre− and Rag1 −/−Cre+ mice induced equivalent levels of antigen-specific FoxP3+ Treg, TGFβR1-deficient CD101+ DCs induced 50% fewer FoxP3+ Treg when compared with CD101+ DCs from Rag1 −/−Cre− littermates (Fig. 7g).

TGFβR1 signalling is required for induction of regulatory T cells by DC in vivo and in vitro. a Experimental scheme for induction of Tregs in vivo. b Representative expression of FoxP3+ by adoptively transferred OTII T cells (Vα2+CD45.1+CD45.2+) from MLN of Rag1 −/−Cre− → WT or Rag1 −/−Cre+ → WT BM chimeric mice 4 days after oral administration of 50 mg OVA (left panels). Scatterplot shows the frequency of FoxP3+ T cells among all Vα2+CD45.1+CD45.2+ T cells (right panel). Each symbol represents an individual animal and the horizontal bar represents the mean. Data are pooled from two independent experiments with nine mice per group. c–e Frequency of IL17A+ c, IFNγ+ d and IL17A+IFNγ+ e T cells among CD45.1+ (residual host) T cells from the SILP of Rag1 −/−Cre− → WT or Rag1 −/−Cre+ → WT BM chimeric mice. Data are pooled from two independent experiments with nine mice per group c or from one experiment with three (Rag1 −/−Cre− → WT) or 5 (Rag1 −/−Cre+ → WT) mice per group d, e. **p < 0.01 and ****p < 0.0001 determined by Student’s t-test. CFSE profile f and expression of FoxP3 g of CD4+ OTII T cells after 3.5 days of co-culture with FACS-purified CD103+CD11b− DC or CD101+ DC from SILP of Rag1 −/−Cre− or Rag1 −/−Cre+ mice in the presence of 0.5 μg ml−1 OVA 323–339 peptide. Data are pooled from at least four individual experiments, with each symbol representing a biological replicate and the horizontal bar representing the mean. ***p < 0.001 determined by Student’s t-test

Feeding OVA alone does not induce high frequencies of effector T cells in vivo35. However, residual endogenous T cells were present in our chimeric mice and analysis of these cells showed a significant reduction in the numbers of IL-17A-producing CD4+ T cells in the small intestinal mucosa of Rag1 −/−Cre+ → WT chimeras compared with Rag1 −/−Cre− → WT chimeras (Fig. 7c). Similarly, IL-17A+IFNγ+ CD4+ T cells, which have been shown to derive from IL-17A+IFNγ− CD4+ T cells39, were also reduced in the Rag1 −/−Cre+ → WT chimeric intestine, whereas IL-17A−IFNγ+ T cells were present in equal proportions in the two groups (Figs. 7d, e). Collectively, these data demonstrate that TGFβR1 signalling is essential for complete maturation of fully functional CD103+CD11b+ DCs in the intestine.

Discussion

CD103+CD11b+ DCs are the predominant population of DCs in the small intestine and are virtually unique to the intestinal mucosa and its draining lymphoid tissues40. Although it is known that CD103+CD11b+ DCs derive from conventional DC progenitors that mature locally after their arrival in the intestine6, 41, the environmental factors responsible for the development of these DCs remain poorly understood. We show here that CD103+CD11b+ DCs are transcriptionally closely related to their CD103−CD11b+ counterparts. However, unlike CD103−CD11b+ DCs, cell intrinsic TGFβR1 signalling is indispensable for the full phenotypic differentiation of CD103+CD11b+ DC in the SILP. Furthermore, using whole-genome analysis and flow cytometric validation, we demonstrate that differentiation to the CD103+CD11b+ phenotype represents more than simple acquisition of CD103 expression and involves significant changes in gene expression. Finally, we demonstrate that aborted DC differentiation in the absence of TGFβR1 signalling renders DCs less able to prime Treg and maintain Th17 in vivo, demonstrating that TGFβR1 signalling in DCs helps maintain immunological homeostasis in the intestine.

We first attempted to address the role of the TGFβ–TGFβR axis in intestinal DC homeostasis by generating CD11c-Cre.Tgfbr1 fl/fl mice, but these developed a lethal systemic inflammatory disease, with all animals dying within 20 weeks. Similar findings were made in mice with CD11c-driven deletion of Tgfbr2 26, but in contrast to that work the wasting disease in our mice was predominantly T-cell driven. This was shown by the fact that T cells in CD11c-Cre.Rosa26-LSL-YFP mice displayed Cre recombinase activity and there was deletion of the Tgfbr1 in T cells from Cre+ CD11c-Cre.Tgfbr1 fl/fl mice. In support of this, the wasting disease in Cre+ mice was prevented by maintaining mice on a Rag1 −/− background and T cells purified from Cre+ mice were able to induce disease in WT mice where they underwent uncontrolled expansion. Similar autoimmune disease was found in mice with CD4-driven deletion of Tgfbr2 28, 42. Together, our findings are consistent with the Cre activity found in T cells in the original description of CD11c-Cre mice25 and they underline the need for extreme caution when interpreting studies employing CD11c-dependent strategies to dissect ‘DC’ function in vivo.

TGFβR1 also controlled the behaviour of CD11c+ cells other than T cells, as intestinal inflammation developed in Rag1 −/−Cre+ recipients of WT T cells and this was associated with a selective defect in CD103+CD11b+ DCs in the intestine of Rag1 −/− CD11c-Cre.Tgfbr1 fl/fl mice. Other mononuclear phagocytes whose homeostasis is controlled by the TGFβ–TGFβR1 axis include microglia in the brain and Langerhans cells in the epidermis20, 22, 43, 44. Interestingly, TGFβ regulates expression of E-cadherin by Langerhans cells23, 45 and Cdh1 was one of the genes we found to be selectively upregulated in CD103+CD11b+ DCs. However, our findings contrast with those from the skin, where TGFβR signalling is required for both Langerhans cell development and for preventing their spontaneous ‘maturation’ and enhanced migration to draining lymph nodes23, 43. An analogous process cannot explain the lack of CD103+CD11b+ DCs in the intestine, as this population was not overrepresented in the draining MLN of Rag1 −/−Cre+ → WT BM chimeras, as would be the case if they had acquired enhanced migratory potential. Furthermore, the total DC pool in the intestine was equivalent in Rag1 −/−Cre− and Rag1 −/−Cre+ mice. Thus, we favour the idea that there is aborted differentiation of CD103+CD11b+ DCs in the absence of TGFβR1 signalling. This was supported by our use of CD101 expression to interrogate the CD11b+ lineage of DCs, where it appeared to be a marker of those cells that are likely to differentiate locally into CD103+CD11b+ DCs. This was first suggested by our transcriptional analysis, which showed that the CD103+CD11b+ and CD103−CD11b+ DCs clustered closely together and identified CD101 as one of the genes that was selectively upregulated on the CD103+CD11b+ subset. Phenotypic analysis confirmed the expression of CD101 protein on virtually all WT CD103+CD11b+ DCs, but showed that a small subset of CD103−CD11b+ DCs also expressed CD101. The fact that these might be the immediate precursors of CD103+CD11b+ DCs would be consistent with the reciprocal increase we found in the CD103−CD11b+ CD101+ population of DCs in CD11c-Cre.Tgfbr1 fl/fl mice. Although TGFβ has been shown previously to induce the expression of CD103 on T cells18, 30, the block in DC development that occurs in the absence of TGFβR1 signalling in vivo did not simply reflect a failure to upregulate CD103, as CD101+CD11b+ DCs in CD11c-Cre.Tgfbr1 fl/fl mice also had reduced expression of SiglecF and TREM1, both of which we found to be specific to this subset at the transcriptional and protein level. On the basis of these findings, we propose that TGFβ is important for the maturation of CD103+CD11b+ DCs from an earlier CD103−CD11b+ stage. However, definitive proof of this idea is lacking and it will be important to establish at exactly what stage TGFβ acts. As we found that all the subsets of mature DCs express the TGFβR1, the selective conditioning effects of TGFβ may occur as DC precursors mature in the mucosa6. Alternatively, there may be an anatomically defined niche in which CD11b+ DCs encounter cells producing sufficient amounts of TGFβ to trigger signalling via the TGFβR. Given the ubiquitous nature of this cytokine, such cells could be of myeloid, mesenchymal or epithelial origin in our Rag1 −/− mice which lack T and B lymphocytes. Resolving these questions will require direct tracking of individual cells within the CD11b lineage, as they differentiate in the mucosa in the presence and absence of TGFβR signalling and these issues are the subject of ongoing work.

Others have reported that CD101 is expressed by some CD11b+ DCs in mouse intestine and that this is retinoic acid receptor dependent16, 46. Although it may also inhibit DC function47 and enhance the production of IL-10 by CD11c+ myeloid cells48, its role in DC development or function in the intestine remains to be defined. CD101 expression has also been linked to the expansion and function of Tregs, including those which can prevent experimental colitis48, 49, as well as a susceptibility gene in the development of type 1 diabetes in non-obese diabetic mice50. As CD103+CD11b+ DCs in the human intestine also express CD10146 and we found varying numbers of CD11b+ DCs to expressed CD101 in other organs, this molecule may provide a useful means for interrogating the tissue specific differentiation of the cDC2 lineage across species. Similarly, the role of TREM1 and SiglecF on CD103+CD11b+ DCs remains unclear, although our findings that these proteins are expressed preferentially by this subset extend other work suggesting this association at the transcriptional level16. Recently, TREM1 has been associated with inflammatory monocytes, where it modulates the function of TLR451. However, it has also been reported to be present on Langerhans cells and to be upregulated on Langerhans cells and BM DCs by hypoxia52, suggesting it may have novel roles on MPs associated with barrier surfaces, especially under conditions of stress.

The selective loss of intestinal CD103+CD11b+ DCs in CD11c-Cre.Tgfbr1 fl/fl mice is similar to that reported in mice deficient in CSF2, CSF2R13, IRF415, 35, SIRPα17, Notch signalling14, 53 and retinoic acid production16, 54. However, these studies did not apply additional discriminatory markers such as CD101, TREM1 or SiglecF, and some did not distinguish bona fide CD103−CD11b+ DCs from CD11b+ CD64/F4/80+ macrophages. As macrophages are much more numerous in LP6, 55, their inclusion could have masked any reciprocal accumulation of CD103−CD11b+ DCs. Therefore, it is unclear whether the TGFβ–TGFβR axis interacts or synergises with any of these other pathways or whteher the absence of each of the molecules interrupts differentiation of the CD11b+ DC lineage at the same stage. Previous studies have implicated the transcription factor RUNX3 in mediating TGFβ dependent effects in DCs56, but whether RUNX3 drives the TGFβ-dependent effects reported here remains unclear.

The exact role of intestinal CD103+CD11b+ DCs has been somewhat unclear, due to apparently contradictory findings from in vitro and in vivo experiments. Whereas this population produces substantial amounts of RA and induces the generation of FoxP3+ Tregs in vitro55, 57, a universal finding from the previous studies of mice lacking CD103+CD11b+ DCs was reduced numbers of Th17 cells in vivo, with normal numbers of FoxP3+ Tregs6, 15, 35, 37 The relative distribution of CD103+CD11b+ DCs along the length of the intestine also correlates with that of Th17 cells and inversely with that of FoxP3+ Tregs55. Therefore, it was notable that we found here that the reduction in CD103+CD11b+ DCs in CD11c-Cre.Tgfbr1 fl/fl mice was not only associated with a lower proportion of endogenous Th17 cells in the intestinal mucosa, but there also was defective generation of antigen specific FoxP3+ Tregs, both in vitro and in vivo. The mechanism underlying these effects remains to be elucidated, but TGFβ is important in the generation of both Treg and Th17 cells36, 58. Therefore, one possibility is that TGFβR signalling in CD103+CD11b+ DCs normally drives TGFβ production via a positive feedback circuit, as has been shown for other DCs59. Although our findings show that the defect in CD103+CD11b+ DCs was associated with reduced numbers of Treg contrasts with the earlier studies, it is important to note that we focused directly on Tregs that were induced in response to their cognate antigen. In contrast, previous work either assessed total Treg numbers, or used surrogate markers to define ‘natural’ and ‘inducible’ Tregs. Alternatively, CD103+CD11b− DCs might compensate for the loss of CD103+CD11b+ DCs in the induction of oral tolerance and Treg,37, 60 and, importantly, we found no defect in the ability of CD103+CD11b− DCs from Cre+ mice to induce Treg in vitro. However, as we did not assess the suppressive functions of these Tregs directly, we cannot rule out the possibility that the FoxP3+ T cells we found to be generated by CD103+CD11b− DCs from Cre+ mice have altered activity despite being present in normal numbers. Furthermore, it is unclear whether the defect in Treg we found contributes to the autoimmunity found in immunocompetent CD11c-Cre.Tgfbr1 fl/fl mice. Discrepancies between different labs on how defects in CD103+CD11b+ DCs might impact on T-cell subsets could also reflect the microbiota present in the various strains or animal facilities. For instance, the ability of CD103+CD11b+ DC to produce IL-23 and drive the differentiation of Th17 cells in vitro can be promoted by TLR5 ligation38, 61. Alternatively, the different strategies used to target CD103+CD11b+ DCs may have distinct consequences for T-cell differentiation and, in particular, our findings that CD11c-mediated Cre activation can have effects on cells other than this specific subset of DC must be taken into account. This could help explain, for example, why contrasting results have been reported on the generation of protective Th17 responses to Citrobacter rodentium infection when CD103+CD11b+ DCs are lacking in human Langerin-DTA transgenic mice and CD11c-Cre.Notch2 fl/fl mice37, 53. Further work is required to elucidate directly how this subset of DC is influenced by different environmental factors and targeting strategies.

Methods

Mice

CD11c-Cre.Tgfbr1 fl/fl mice on a C57BL/6 background were generated as described previously23 and crossed to Rag1 −/− mice (Jackson Laboratories) to generate Rag1 −/− CD11c-Cre.Tgfbr1 fl/fl mice. Cre− littermates were used as experimental controls in all the experiments presented. WT C57BL/6 (CD45.2+) mice were obtained from Harlan Olac (Bicester, UK), whereas C57BL/6.SJL (CD45.1+) mice, C57BL/6.SJL × C57Bl/6 (CD45.1+ × CD45.2+) and OTII OVA-specific TcR transgenic mice on the CD45.1+ background were bred in house. All mice were used at 6–12 weeks of age, and male and female mice were used throughout the study. Transgenic and control mice were sex-matched within experiments. All mice were bred and maintained in specified pathogen-free conditions at the Central Research Facility at the University of Glasgow under a UK Home Office Project Licence and approved by the University of Glasgow Local Ethical Review Panel, or at the University Medical Centre, Rotterdam, and approved by the Animal Experiments Committee DEC–Consult of the Erasmus University Medical Center Rotterdam. No randomization or blinding was performed.

Generation of bone marrow chimeric mice

To generate mixed chimeras, 8–10-week-old CD45.1+ WT mice were lethally irradiated with two doses of 5 Gy 1 h apart before being reconstituted immediately with 5 × 106 BM cells from CD45.2+ Rag1 −/−CD11c-Cre.Tgfbr1 fl/fl or Rag1 −/− Tgfbr1 fl/fl mice together with CD45.1+ × CD45.2+ WT BM at a ratio of 1:1. In some experiments, CD45.1+ × CD45.2+ mice were used as the recipient mice and CD45.1+ WT mice used as the WT donor. To generate full chimeras, CD45.1+ WT mice were given BM cells from CD45.2+ Rag1 −/−CD11c-Cre.Tgfbr1 fl/fl or Rag1 −/− Tgfbr1 fl/fl mice. Chimerism was assessed at least 8 weeks after reconstitution.

Generation of Treg cells in vivo

Eight to 10 weeks after reconstitution, Rag1 −/− CD11c-Cre.Tgfbr1 fl/fl and Rag1 −/− Tgfbr1 fl/fl mice → CD45.1+ WT chimeric received 5 × 105 purified CD4+ T cells from the spleen and lymph nodes of CD45.2+ WT mice intravenously. Six days later mice were adoptively transferred with 5 × 105 fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) sorted naive CD4+CD62L+CD45.1+/CD45.2+ OT II cells intravenously, before being fed 50 mg OVA 24 h later. FTY720 (1 mg kg−1; Cayman Chemical Company) was injected intraperitoneally 2 and 4 days after OTII T-cell transfer and mice were culled 5 days after T-cell transfer for assessment of Foxp3+ expression by CD4+Vα2+ transgenic T cells in mesenteric lymph nodes using intracellular FACS analysis.

Induction of T-cell-dependent colitis

CD3+MHC-IIneg T cells were sorted from the spleens of C57BL/6 CD45.1 mice, resuspended in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and 5 × 106 T cells were injected intravenously into Rag1 −/− CD11c-Cre.Tgfbr1 fl/fl (Rag1 −/−Cre+) mice and Rag1 −/− Tgfbr1 fl/fl (Rag1 −/−Cre−) littermates. Body weight was monitored twice a week and the recipients were killed when 20% weight loss occurred (10–17 weeks post transfer). The severity of bowel inflammation was evaluated by scoring of histological sections (adapted from ref. 62).

Preparation of single-cell suspensions

To isolate small intestinal leukocytes, small intestine were flushed with calcium/magnesium-free (CMF) Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) 2% fetal calf serum (FCS) (both Gibco, Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) and PPs excised. The intestines were opened longitudinally, washed again in HBSS 2% FCS and cut into 0.5 cm segments, which were then incubated twice in HBSS with 2 mM EDTA at 37 °C with shaking for 20 min. Supernatants were discarded and intestinal tissue digested with 1 mg ml−1 collagenase VIII (Sigma-Aldrich) in complete RPMI 1640 containing 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 μg ml−1 penicillin, 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin, 1.25 μg ml−1 Fungizone and 10% FCS (all Gibco, Invitrogen) at 37 °C with shaking for 20 min. Cell suspensions were passed through 100 μm and then 40 μm filters (BD Falcon) and stained for flow cytometry. To isolate colonic leukocytes, colons were excised and soaked in PBS. After removing all fat and faeces, the colons were opened longitudinally, washed in HBSS 2% FCS and cut into 0.5 cm sections. The tissue was then shaken vigorously in 10 ml HBSS/2% FCS and the supernatant was discarded. To remove the epithelial layer, 10 ml CMF HBSS containing 2 mM EDTA was then added, the tube placed in a shaking incubator for 15 min at 37 °C, before being shaken vigorously and the supernatant discarded. Tissue segments were washed in 10 ml fresh CMF HBSS, before a second incubation in CMF HBSS/2 mM EDTA, the wash step was repeated and the remaining tissue was digested with pre-warmed ‘enzyme cocktail’ containing 1.25 mg ml−1 collagenase D (Roche), 0.85 mg ml–1 collagenase V (Sigma-Aldrich), 1 mg ml−1 dispase (Gibco, Invitrogen) and 30 U ml−1 DNase (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) in complete RPMI 1640 for 30–45 min in a shaking incubator at 37 °C. The resulting cell suspension was passed through a 40-μm cell strainer and washed twice in FACS buffer (2% FCS/2mm EDTA/PBS). Cells were counted and stained for flow cytometry. To isolate leukocytes from MLNs, MLNs were minced with scissors and incubated with 1 mg ml−1 collagenase D in CMF HBSS for 45 min in a shaking incubator at 37 °C. After digestion, cells were passed through a 100-μm filter and kept on ice until further use63. Lungs were removed from perfused mice, chopped finely and digested in pre-warmed ‘enzyme cocktail’ for 45 min in a shaking incubator at 37 °C before being passed through an 100 μm strainer followed by centrifugation at 400 g for 5 min. Spleens were chopped finely and digested in HBSS with 1 mg ml−1 collagenase D for 45 min in a shaking incubator at 37 °C before being passed through a 100 μm strainer followed by centrifugation at 400 g for 5 min. Cells were resuspended in FACS buffer, counted and kept on ice until staining for flow cytometry.

T cell and DC co-cultures

A total of 12,500 CD45+CD11c+MHCII+CD64−CD101+CD11b+ DCs were FACS purified from the SILP of Rag1 −/−CD11c-Cre.Tgfbr1 fl/fl or Rag1 −/− Tgfbr1 fl/fl mice before being pulsed with 0.5 μg ml−1 of OVA323-339 peptide (Genosys, Sigma) in 100 μl for 30 min at 37 °C in 5% CO2 in RPMI 1640 containing 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 μg ml−1 penicillin, 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin, 1.25 μg ml−1 Fungizone and 10% FCS; all from Gibco) in 96-well round-bottom plates. After 30 min, 1 × 105 CFSE-labelled naive CD4+CD62L+ T cells FACS sorted from the lymph nodes of OTII.CD45.1+ TcR transgenic mice were added and cultured for 3.5 days at 37 °C in 5% CO2. After culture, responding OTII cells were assessed for expression of FoxP3 and CFSE dilution by flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry

Following incubation with purified anti-CD16/CD32 for 10 min at 4 °C, 1−10 × 106 cells were stained at 4 °C in the dark as described previously63, 64 using the antibodies listed in Supplementary Table 6 and analysed using an LSR II or FACSAriaI/III cytometer (BD Biosciences) and FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Genomic PCR

Cre-mediated deletion of Tgfbr1 was analysed by genomic PCR65. The floxed third exon of Tgfbr1 was identified by a 250-bp band, whereas excision was demonstrated by a 350-bp band (see Supplementary Table 7).

Quantitative RT-PCR

mRNA was extracted from cells using the GenElute mammalian total RNA Miniprep kit (Sigma-Aldrich) and complementary DNA was synthesized with SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. TaqMan real-time quantitative PCR assays were designed using Universal ProbeLibrary (Roche) to determine transcript levels of the indicated genes using the primers listed in Supplementary Table 8. Expression levels were normalized to the control gene Gapdh or Abl as indicated. All reactions were run on a 7900HT Fast Real Time PCR machine (Applied Biosystems).

Histology

Tissues were snap-frozen, cut into 6 µm sections and fixed in acetone/0.02% H2O2. For detection of CD3 (Dako Heverlee) and Ki67 (Novocastra), endogenous peroxidases were quenched with 3% H2O2 in methanol for 20 min. After microwaving in citrate buffer (10 mM, pH 6.0) for antigen retrieval, sections were blocked for 1 h in 10 mM Tris, 5 mM EDTA, 0.15 M NaCl, 0.05% Tween-20 and 10% normal mouse serum (NMS), before being stained overnight with primary antibodies against CD4 (GK1.5) and CD8 (Lyt2) (both from Dako) at 4 °C in PBS/0.1% BSA. After washing, biotinylated rabbit anti-rat secondary antibody (Dako) or goat anti-rabbit serum was added in PBS/0.1% BSA/2% NMS for 1 h at room temperature. Enzyme activity was revealed by using the Vectastain ABC kit (Vector Laboratories). Aminoethylcarbazole (Sigma) or 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich) was used as a chromogen for horseradish peroxidase activity. The sections were counterstained with haematoxylin and mounted with glycerol-gelatin. The slides were scanned with the NanoZoomer 2.0HT scanner (Hamamatsu) and analysed with the NanoZoomer Digital Pathology programme.

Microarray analysis

A total of 100,000 cells from each DC subset and CD45+Ly6C−MHCII+CD64+ CD11b+ macrophages were FACS purified from SI LP and total RNA extracted with the RNeasy Micro kit (Qiagen). Quantity, quality and absence of genomic DNA were assessed using a Bioanalyser (Agilent). For microarray analysis, 50–450 ng of total RNA was retrieved per biological sample, with RIN values always above 8.25 ng total RNA was used for each sample for synthesis of biotinylated double stranded cDNA, using the NuGEN Ovation Pico WTA System V2 kit and the NuGEN Encore Biotin Module kit, according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Following fragmentation and end-labelling, 2 µg of cDNA were hybridized for 16 h at 45 °C on GeneChip Mouse Gene 1.0 ST arrays (Affymetrix), interrogating 28,853 genes represented by ~27 probes spread across the full length of the gene. The chips were washed, stained in the GeneChip Fluidic Station 450 (Affymetrix) and scanned with the GeneChip Scanner 3,000 7 G (Affymetrix) at a resolution of 0.7 µm. Raw data (.cel intensity files) were extracted from the scanned images using the Affymetrix GeneChip Command Console version 3.2. After quality control using R/Bioconductor, the Robust Multi-array Average procedure was used to normalize data within arrays (probeset summarization, background correction and log2-transformation) and between arrays (quantile normalization). Only probesets that mapped uniquely to one gene were used and for each gene, the probeset with the highest expression level was used.

Cytometric bead assay

Splenocytes (1 × 106) were cultured overnight in 500 µl medium and supernatants were stored at −20 °C before analysis of IL2, IL17A and IFNγ levels using a cytometric bead assay (Bender MedSystems) with a FACS Canto-II (BD Biosciences) and FCAP Array software (BD Biosciences).

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism. Student’s t-test was used to compare two groups, while multiple groups were compared using analysis of variance or Student’s t-tests with appropriate corrections as detailed in the legends. A p-value of 0.05 was considered significant.

Data availability

Microarray data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus public database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) with the primary accession code GSE100393. The other data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Mowat, A. M. Anatomical basis of tolerance and immunity to intestinal antigens. Nat. Rev. 3, 331–341 (2003).

Worbs, T. et al. Oral tolerance originates in the intestinal immune system and relies on antigen carriage by dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 203, 519–527 (2006).

Houston, S. A. et al. The lymph nodes draining the small intestine and colon are anatomically separate and immunologically distinct. Mucosal Immunol. 9, 468–478 (2016).

Veenbergen, S. et al. Colonic tolerance develops in the iliac lymph nodes and can be established independent of CD103(+) dendritic cells. Mucosal Immunol. 9, 894–906 (2016).

Cerovic, V., Bain, C. C., Mowat, A. M. & Milling, S. W. F. Intestinal macrophages and dendritic cells: what’s the difference? Trends Immunol. 35, 270–277 (2014).

Scott, C. L. et al. CCR2(+)CD103(−) intestinal dendritic cells develop from DC-committed precursors and induce interleukin-17 production by T cells. Mucosal Immunol. 8, 327–339 (2015).

Cerovic, V. et al. Intestinal CD103(−) dendritic cells migrate in lymph and prime effector T cells. Mucosal Immunol. 6, 104–113 (2013).

Persson, E. K., Scott, C. L., Mowat, A. M. & Agace, W. W. Dendritic cell subsets in the intestinal lamina propria: Ontogeny and function. Eur. J. Immunol. 43, 3098–3107 (2013).

Crozat, K. et al. Cutting edge: expression of XCR1 defines mouse lymphoid-tissue resident and migratory dendritic cells of the CD8α+type. J. Immunol. 187, 4411–4415 (2011).

Cerovic, V. et al. Lymph-borne CD8α(+) dendritic cells are uniquely able to cross-prime CD8(+) T cells with antigen acquired from intestinal epithelial cells. Mucosal Immunol. 8, 38–48 (2014).

Luda, K. M. et al. IRF8 transcription-factor-dependent classical dendritic cells are essential for intestinal T cell homeostasis. Immunity 44, 860–874 (2016).

Guilliams, M. et al. Dendritic cells, monocytes and macrophages: a unified nomenclature based on ontogeny. Nat. Rev. 14, 571–578 (2014).

Greter, M. et al. GM-CSF controls nonlymphoid tissue dendritic cell homeostasis but is dispensable for the differentiation of inflammatory dendritic cells. Immunity 36, 1031–1046 (2012).

Lewis, K. L. et al. Notch2 receptor signaling controls functional differentiation of dendritic cells in the spleen and intestine. Immunity 35, 780–791 (2011).

Schlitzer, A. et al. IRF4 transcription factor-dependent CD11b+ dendritic cells in human and mouse control mucosal IL-17 cytokine responses. Immunity 38, 970–983 (2013).

Zeng, R., Bscheider, M., Lahl, K., Lee, M. & Butcher, E. C. Generation and transcriptional programming of intestinal dendritic cells: essential role of retinoic acid. Mucosal Immunol. 9, 183–193 (2016).

Scott, C. L., Tfp, Z. M., Beckham, K. S. H., Douce, G. & Mowat, A. M. Signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPα) regulates the homeostasis of CD103(+) CD11b(+) DCs in the intestinal lamina propria. Eur. J. Immunol. 44, 3658–3668 (2014).

Kilshaw, P. J. & Murant, S. J. A new surface antigen on intraepithelial lymphocytes in the intestine. Eur. J. Immunol. 20, 2201–2207 (1990).

Annacker, O. et al. Essential role for CD103 in the T cell-mediated regulation of experimental colitis. J. Exp. Med. 202, 1051–1061 (2005).

Butovsky, O. et al. Identification of a unique TGF-β-dependent molecular and functional signature in microglia. Nat. Neurosci. 17, 131–143 (2014).

Borkowski, T. A., Letterio, J. J., Farr, A. G. & Udey, M. C. A role for endogenous transforming growth factor beta 1 in Langerhans cell biology: the skin of transforming growth factor beta 1 null mice is devoid of epidermal Langerhans cells. J. Exp. Med. 184, 2417–2422 (1996).

Zahner, S. P. et al. Conditional deletion of TGF-βR1 using Langerin-Cre mice results in Langerhans cell deficiency and reduced contact hypersensitivity. J. Immunol. 187, 5069–5076 (2011).

Kel, J. M., Girard-Madoux, M. J. H., Reizis, B. & Clausen, B. E. TGF-beta is required to maintain the pool of immature Langerhans cells in the epidermis. J. Immunol. 185, 3248–3255 (2010).

Bain, C. C. et al. Constant replenishment from circulating monocytes maintains the macrophage pool in the intestine of adult mice. Nat. Immunol. 15, 929–937 (2014).

Caton, M. L., Smith-Raska, M. R. & Reizis, B. Notch-RBP-J signaling controls the homeostasis of CD8(−) dendritic cells in the spleen. J. Exp. Med. 204, 1653–1664 (2007).

Ramalingam, R. et al. Dendritic cell-specific disruption of TGF-β receptor II leads to altered regulatory T cell phenotype and spontaneous multiorgan autoimmunity. J. Immunol. 189, 3878–3893 (2012).

Gorelik, L. & Flavell, R. A. Abrogation of TGFbeta signaling in T cells leads to spontaneous T cell differentiation and autoimmune disease. Immunity 12, 171–181 (2000).

Marie, J. C., Liggitt, D. & Rudensky, A. Y. Cellular mechanisms of fatal early-onset autoimmunity in mice with the T cell-specific targeting of transforming growth factor-beta receptor. Immunity 25, 441–454 (2006).

Tamoutounour, S. et al. CD64 distinguishes macrophages from dendritic cells in the gut and reveals the Th1-inducing role of mesenteric lymph node macrophages during colitis. Eur. J. Immunol. 42, 3150–3166 (2012).

Schön, M. P. et al. Mucosal T lymphocyte numbers are selectively reduced in integrin alpha E (CD103)-deficient mice. J. Immunol. 162, 6641–6649 (1999).

van de Laar, L. et al. Yolk Sac macrophages, fetal liver, and adult monocytes can colonize an empty niche and develop into functional tissue-resident macrophages. Immunity 44, 755–768 (2016).

Scott, C. L. et al. The transcription factor Zeb2 regulates development of conventional and plasmacytoid DCs by repressing Id2. J. Exp. Med. 213, 897–911 (2016).

Miller, J. C. et al. Deciphering the transcriptional network of the dendritic cell lineage. Nat. Immunol. 13, 888–899 (2013).

Carpentier, S. et al. Comparative genomics analysis of mononuclear phagocyte subsets confirms homology between lymphoid tissue-resident and dermal XCR1(+) DCs in mouse and human and distinguishes them from Langerhans cells. J. Immunol. Methods 432, 35–49 (2016).

Persson, E. K. et al. IRF4 transcription-factor-dependent CD103(+)CD11b(+) dendritic cells drive mucosal T helper 17 cell differentiation. Immunity 38, 958–969 (2013).

Coombes, J. L. et al. A functionally specialized population of mucosal CD103+DCs induces Foxp3+regulatory T cells via a TGF-beta and retinoic acid-dependent mechanism. J. Exp. Med. 204, 1757–1764 (2007).

Welty, N. E. et al. Intestinal lamina propria dendritic cells maintain T cell homeostasis but do not affect commensalism. J. Exp. Med. 210, 2011–2024 (2013).

Kinnebrew, M. A. et al. Interleukin 23 production by intestinal CD103(+)CD11b(+) dendritic cells in response to bacterial flagellin enhances mucosal innate immune defense. Immunity 36, 276–287 (2012).

Hirota, K. et al. Fate mapping of IL-17-producing T cells in inflammatory responses. Nat. Immunol. 12, 255–263 (2011).

Mowat, A. M. & Agace, W. W. Regional specialization within the intestinal immune system. Nat. Rev. 14, 667–685 (2014).

Schraml, B. U. et al. Genetic tracing via DNGR-1 expression history defines dendritic cells as a hematopoietic lineage. Cell 154, 843–858 (2013).

Li, M. O., Sanjabi, S. & Flavell, R. A. Transforming growth factor-beta controls development, homeostasis, and tolerance of T cells by regulatory T cell-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Immunity 25, 455–471 (2006).

Bobr, A. et al. Autocrine/paracrine TGF-β1 inhibits langerhans cell migration. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 10492–10497 (2012).

Mohammed, J. et al. Stromal cells control the epithelial residence of DCs and memory T cells by regulated activation of TGF-β. Nat. Immunol. 17, 414–421 (2016).

Bauer, T. et al. Identification of Axl as a downstream effector of TGF-β1 during Langerhans cell differentiation and epidermal homeostasis. J. Exp. Med. 209, 2033–2047 (2012).

Watchmaker, P. B. et al. Comparative transcriptional and functional profiling defines conserved programs of intestinal DC differentiation in humans and mice. Nat. Immunol. 15, 98–108 (2014).

Bouloc, A., Bagot, M., Delaire, S., Bensussan, A. & Boumsell, L. Triggering CD101 molecule on human cutaneous dendritic cells inhibits T cell proliferation via IL-10 production. Eur. J. Immunol. 30, 3132–3139 (2000).

Schey, R. et al. CD101 inhibits the expansion of colitogenic T cells. Mucosal Immunol. 9, 1205–1217 (2016).

Fernandez, I. et al. CD101 surface expression discriminates potency among murine FoxP3+regulatory T cells. J. Immunol. 179, 2808–2814 (2007).

Rainbow, D. B. et al. Evidence that Cd101 is an autoimmune diabetes gene in nonobese diabetic mice. J. Immunol. 187, 325–336 (2011).

Ornatowska, M. et al. Functional genomics of silencing TREM-1 on TLR4 signaling in macrophages. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 293, L1377–L1384 (2007).

Pierobon, D. et al. Chronic hypoxia reprograms human immature dendritic cells by inducing a proinflammatory phenotype and TREM-1 expression. Eur. J. Immunol. 43, 949–966 (2013).

Satpathy, A. T. et al. Notch2-dependent classical dendritic cells orchestrate intestinal immunity to attaching-and-effacing bacterial pathogens. Nat. Immunol. 14, 937–948 (2013).

Klebanoff, C. A. et al. Retinoic acid controls the homeostasis of pre-cDC-derived splenic and intestinal dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 210, 1961–1976 (2013).

Denning, T. L. et al. Functional specializations of intestinal dendritic cell and macrophage subsets that control Th17 and regulatory T cell responses are dependent on the T cell/APC ratio, source of mouse strain, and regional localization. J. Immunol. 187, 733–747 (2011).

Fainaru, O. et al. Runx3 regulates mouse TGF-beta-mediated dendritic cell function and its absence results in airway inflammation. EMBO. J 23, 969–979 (2004).

Fujimoto, K. et al. A new subset of CD103+CD8alpha+dendritic cells in the small intestine expresses TLR3, TLR7, and TLR9 and induces Th1 response and CTL activity. J. Immunol. 186, 6287–6295 (2011).

Veldhoen, M., Hocking, R. J., Atkins, C. J., Locksley, R. M. & Stockinger, B. TGFbeta in the context of an inflammatory cytokine milieu supports de novo differentiation of IL-17-producing T cells. Immunity 24, 179–189 (2006).

Kashiwagi, I. et al. Smad2 and Smad3 inversely regulate TGF-β autoinduction in Clostridium butyricum-activated dendritic cells. Immunity 43, 65–79 (2015).

Esterházy, D. et al. Classical dendritic cells are required for dietary antigen-mediated induction of peripheral Treg cells and tolerance. Nat. Immunol. 17, 545–555 (2016).

Uematsu, S. et al. Regulation of humoral and cellular gut immunity by lamina propria dendritic cells expressing Toll-like receptor 5. Nat. Immunol. 9, 769–776 (2008).

van Lierop, P. P. E. et al. T-cell regulation of neutrophil infiltrate at the early stages of a murine colitis model. Inflamm. Bowel. Dis. 16, 442–451 (2010).

Scott, C. L., Bain, C. C. & Mowat, A. M. Isolation and identification of intestinal myeloid cells. Methods Mol. Biol. 1559, 223–239 (2017).

Bain, C. C. & Mowat, A. M. CD200 receptor and macrophage function in the intestine. Immunobiology 217, 643–651 (2011).

Larsson, J. et al. Abnormal angiogenesis but intact hematopoietic potential in TGF-beta type I receptor-deficient mice. EMBO. J 20, 1663–1673 (2001).

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs V. Cerovic and S. Milling for critical reading of the manuscript, Inge Brouwers-Haspels for expert technical assistance and Diane Vaughan at the Glasgow Flow Cytometry Facility for help with sorting. Violaine Alunni and Christelle Thibault-Carpentier (Plateforme Biopuces et Séquençage de l’IGBMC, Strasbourg, France) performed the microarray experiments (http://www-microarrays.u-strasbg.fr), with assistance from Emeline Pollet (CIML). This work was supported by Wellcome Trust UK Project Grant 094763 to C.C.B. and A.M.M., Wellcome Trust PhD Studentships 089892 (C.L.S.) and 096988 (T.F.P.Z.-M.), the Medical Research Council UK and grants from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO, VIDI 917-76-365) to B.E.C. C.L.S. is supported by a Horizon 2020 Marie Curie Intra-European Fellowship (IEF). B.E.C. is currently supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) and the Research Centre for Immunotherapy (FZI) Mainz.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Performed experiments and data analysis: C.C.B., J.M., C.L.S., J.M.K., M.J.H.G.-M., T.F.P.Z.-M., J.O.-B. and D.L.-K. Transcriptomic analyses: C.L.S., L.M., Y.S., S.H., M.D., T.L. and B.M. Conceived experiments: C.C.B., J.M., J.N.S., B.E.C. and A.M.M. Project supervision: C.C.B., J.N.S., B.E.C. and A.M.M. Wrote the manuscript: C.C.B., J.M., M.J.H.G.-M., B.E.C., C.L.S. and A.M.M.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bain, C.C., Montgomery, J., Scott, C.L. et al. TGFβR signalling controls CD103+CD11b+ dendritic cell development in the intestine. Nat Commun 8, 620 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-00658-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-00658-6

This article is cited by

-

Indole-3-acetic acid ameliorates dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis via the ERK signaling pathway

Archives of Pharmacal Research (2024)

-

TGFβ control of immune responses in cancer: a holistic immuno-oncology perspective

Nature Reviews Immunology (2023)

-

Dedicated macrophages organize and maintain the enteric nervous system

Nature (2023)

-

Regulation of intestinal immunity by dietary fatty acids

Mucosal Immunology (2022)

-

Dendritic cell functions in the inductive and effector sites of intestinal immunity

Mucosal Immunology (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.