Abstract

The arms race between tetrodotoxin-bearing Pacific newts (Taricha) and their garter snake predators (Thamnophis) in western North America has become a classic example of coevolution, shedding light on predator-prey dynamics, the molecular basis of adaptation, and patterns of convergent evolution. Newts are defended by tetrodotoxin (TTX), a neurotoxin that binds to voltage-gated sodium channels (Nav proteins), arresting electrical activity in nerves and muscles and paralyzing would-be predators. However, populations of the common garter snake (T. sirtalis) have overcome this defense, largely through polymorphism at the locus SCN4A, which renders the encoded protein (Nav1.4) less vulnerable to TTX. Previous work suggests that SCN4A commonly shows extreme deviations from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) in these populations, which has been interpreted as the result of intense selection imposed by newts. Here we show that much of this apparent deviation can be attributed to sex linkage of SCN4A. Using genomic data and quantitative PCR, we show that SCN4A is on the Z chromosome in Thamnophis and other advanced snakes. Taking Z-linkage into account, we find that most apparent deviations from HWE can be explained by female hemizygosity rather than low heterozygosity. Sex linkage can affect mutation rates, selection, and drift, and our results suggest that Z-linkage of SCN4A may make significant contributions to the overall dynamics of the coevolutionary arms race between newts and snakes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In western North America, Pacific newts (Taricha) use the potent neurotoxin tetrodotoxin (TTX) as an antipredator defense (Brodie 1968; Hanifin et al. 1999; Hanifin et al. 2008). Common garter snake (Thamnophis sirtalis) populations inhabiting the same areas as toxic newts have evolved matching levels of TTX resistance as the result of an arms race between predator and prey (Brodie and Brodie 1990; Brodie et al. 2002). Resistance in snakes is largely attributable to mutations in voltage-gated sodium channels (Nav), the proteins that are the molecular targets of TTX (Geffeney et al. 2005; Feldman et al. 2009; McGlothlin et al. 2016). Specific residues in the outer pore (p-loop) of Nav channels ligate to TTX (Fozzard and Lipkind 2010), and mutations at these sites prevent TTX from binding to the pore and blocking the movement of sodium through these channels (Geffeney et al. 2005; Feldman et al. 2009; Hague et al. 2017). Polymorphism at one locus in particular, SCN4A, which encodes the skeletal muscle voltage-gated sodium channel (Nav1.4), appears largely responsible for variation in TTX resistance across populations of T. sirtalis: populations vary in the frequency of mutations that modify the channel p-loop, and thus in TTX resistance (Geffeney et al. 2005; Feldman et al. 2010; Hague et al. 2017). Such mutations have arisen independently in multiple garter snake populations, as well as in other snake species that consume TTX-bearing amphibians (Feldman et al. 2009, 2012; Hague et al. 2017). Due to its well-defined and relatively simple genetic basis, the evolution of TTX resistance in snakes has been studied extensively and has contributed to our understanding of the process of adaptation, predator-prey interactions, and coevolutionary dynamics (Brodie and Brodie 2015).

Because phenotypic TTX resistance in T. sirtalis can be predicted reliably from the sequence of the p-loop regions of SCN4A (Geffeney et al. 2005; Feldman et al. 2010; Hague et al. 2017), population genetic studies of this locus have the potential to provide insight into the evolutionary history and dynamics of phenotypic TTX resistance. In a recent survey of SCN4A allelic variation across T. sirtalis populations throughout the western United States, Hague et al. (2017) found that evolution of the TTX resistance phenotype follows a predictable trajectory, with the same p-loop mutation (I1561V; conferring moderate resistance) appearing before additional mutations that confer extreme resistance (D1568N-G1569V and G1566A). Intriguingly, almost every population surveyed showed deviations from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE), with observed heterozygosity significantly lower than expected at the SCN4A locus (Hague et al. 2017). This pattern, which was consistent with earlier work by Feldman et al. (2010) in T. sirtalis and T. atratus populations, was interpreted as the result of strong positive selection for resistant alleles. However, because selection rarely results in extreme deviations from HWE (Lachance 2009), it is likely that strong selection is not the only factor underlying the unusually low number of heterozygotes observed.

One factor that may contribute to an apparent reduction in heterozygosity is sex linkage (Crow and Kimura 1970). Advanced snakes (Caenophidia) have a ZW chromosome system, with females, as the heterogametic sex, having a single copy of the Z chromosome, and males, as the homogametic sex, having two copies of the Z chromosome (Pokorná and Kratochvíl 2009; Rovatsos et al. 2015). If SCN4A were located on the Z chromosome, cryptic hemizygosity in females would create apparent deviations from HWE. Here, we test the hypothesis that Z-linkage of SCN4A accounts for the low-observed heterozygosity for this gene of major effect. We use the newly sequenced genome of the prairie rattlesnake (Crotalus viridis), which has been assembled to the chromosome level (Schield et al. 2019), to identify the genomic locations of all nine members of the voltage-gated sodium channel gene family (Zakon et al. 2011), including SCN4A. Next, we use quantitative PCR to test for sex differences in ortholog copy number to confirm that chromosomal locations are conserved between the viperid C. viridis and the colubrid T. sirtalis, both of which are members of the advanced snake clade Colubroidea, but represent distinct lineages separated by ~61 million years (Zheng and Wiens 2016). We then analyze genetic data from populations previously studied by Hague et al. (2017) to determine whether gene structure affects neutral expectations of allele frequency and heterozygosity. Our results alter the conclusions about genetic variation among T. sirtalis populations and have implications for our understanding of the arms race between garter snakes and newts and the repeated evolution of TTX resistance in snakes.

Methods and results

Four voltage-gated sodium channel genes are located on the Z sex chromosome of Crotalus viridis

We used the reciprocal best BLAST hit method (Moreno-Hagelsieb and Latimer 2007) to locate the nine members of the voltage-gated sodium channel gene family on the genomic scaffolds of C. viridis, using predicted T. sirtalis mRNA sequences as queries (Table 1). The C. viridis genome consists of eight pairs of macrochromosomes (including the Z and W sex chromosomes), and several microchromosomes (Schield et al. 2019). Genes SCN1A, SCN2A, SCN3A, and SCN9A aligned in tandem to macrochromosome 1, SCN8A aligned to macrochromosome 2, SCN5A, SCN10A, and SCN11A aligned in tandem to the q arm of the Z sex chromosome, and SCN4A aligned near the centromere of the Z chromosome (Table 1 and Fig. 1a).

a Schematic of the chromosomal structure of voltage-gated sodium channel genes in C. viridis. SCN1A, SCN2A, SCN3A, and SCN9A reside on autosomal chromosome 1, SCN8A resides on autosomal chromosome 2, and SCN4A, SCN5A, SCN10A, and SCN11A reside on the Z sex chromosome, >30 million base-pairs from the recombining pseudoautosomal region (PAR; dark gray box). Right-facing arrows indicate the gene is located on the forward strand, whereas left-facing arrows indicate the reverse strand. Dark gray circles represent centromeres. Gene locations are approximate and not to scale. b Ratios of female:male gene copy numbers for the nine voltage-gated sodium channel genes, and sex-linked gene TANC2, based on pairwise comparisons of gene copy number qPCR from three female and three male T. sirtalis individuals. Sex differences in copy number were analyzed using unpaired t-tests, but male–female pairs were formed at random to generate female:male ratios for visualization. Black dotted lines indicate the expected female:male ratios for autosomal and sex-linked genes (1.0 and 0.5, respectively).

Z-linkage of SCN4A, SCN5A, SCN10A, and SCN11A appears to date to the origin of snake Z chromosome, which is highly conserved in advanced snakes (Rovatsos et al. 2015). The colubrid Z chromosome is homologous to autosomal macrochromosome 6 in Anolis lizards (Vicoso et al. 2013), which in turn aligns with microchromosome 27 and a portion of macrochromosome 2 in chicken (Alföldi et al. 2011). As expected, BLAST alignments place all four of these SCN loci on chromosome 6 in Anolis (Genbank accession NC_014781.1; Alfödi et al. 2011). Further, SCN5A, SCN10A, and SCN11A are found on chicken macrochromosome 2 (NC_006089.5) and SCN4A is found on chicken microchromosome 27 (NC_006114.5; Hillier et al. 2004).

Thamnophis sirtalis females are hemizygous for voltage-gated sodium channel genes SCN4A, SCN5A, SCN10A, and SCN11A

We used tissue samples from a total of seven male and seven female T. sirtalis individuals to test whether the genetic structure of SCN4A is conserved between C. viridis and T. sirtalis. We extracted genomic DNA using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA) and treated DNA with 4 µl of RNase A (100 mg/ml) to avoid potential mRNA contamination. To confirm the sex of each snake, we designed PCR primers following methods from Laopichienpong et al. (2017). These primers target both the Z and W paralogs of the sex-linked gene CTNNB1 (corresponding to T. sirtalis genomic scaffolds LFLD01132464.1 and LFLD01095040.1, respectively (Perry et al. 2018)), producing two amplicons of 1289 and 1488 bp from female DNA and a single amplicon of 1488 bp from male DNA, due to an intron length polymorphism at these loci (Table 2). We performed sexing PCR using 1× GoTaq Green Master Mix (Promega, Madison, WI), 0.5 µM of each forward and reverse primer, and 20 ng of genomic DNA in a 20 µl total volume with the following cycling conditions: denaturation at 94 °C for 2 min, followed by 30 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 63 °C for 45 s, 72 °C for 1 min, and a final extension of 72 °C for 5 min.

Previous studies have used qPCR (Rovatsos et al. 2015) and next-generation sequencing (Vicoso et al. 2013) to identify Z-linked loci in snakes by quantifying the relative ortholog copy numbers in females and males. Following these methods, we used qPCR to determine whether SCN loci are hemizygous or autosomal/pseudoautosomal in garter snakes. We used Primer3 (Untergasser et al. 2012) to design qPCR primers targeting exons of the nine SCN genes, the Z-linked control gene TANC2, the growth hormone gene GH1, which maintains a close physical linkage with SCN4A in humans (Bennani-Baiti et al. 1995) as well as reptiles (Alföldi et al. 2011; Schield et al. 2019), and the single-copy normalizing gene EEF1A1 (Table 2). We confirmed the specificity of all primers by aligning them to T. sirtalis genomic scaffolds (Perry et al. 2018) with Primer-BLAST (Ye et al. 2012), and additionally by post-PCR dissociation curve analyses. We used DNA samples from three male and three female T. sirtalis individuals previously sampled from the Willow Creek population in northern California (Brodie et al. 2002; Feldman et al. 2009) for pairwise comparisons of copy numbers of all nine sodium channel genes. We performed qPCR in 96-well plates using 1× Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems Inc., Carlsbad, CA), 0.1 µM of each forward and reverse primer, and 20 ng of genomic DNA per reaction in a 20 µl total volume. We used a CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) with an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 20 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 3 s and 60 °C for 30 s. We ran each sample in triplicate and used the average Ct value across replicates. In order to compare samples across plates, we used the BioRad CFX Manager software v3.1 to manually set a common baseline threshold that crossed amplification curves within the geometric phases across all of the plates assayed. We plotted data using the ggplot2 package (Wickham 2009) in R (R Development Core Team 2018).

We calculated relative gene copy numbers in females versus males using the delta–delta Ct method (Pfaffl 2001):

Using this formula, we expect ratios of ~1.0 for autosomal or pseudoautosomal genes and 0.5 for Z-linked genes with divergence between the Z and W copies (Rovatsos et al. 2015).

Consistent with our observations in the C. viridis genome, we found that female T. sirtalis snakes are hemizygous for voltage-gated sodium channel genes SCN4A, SCN5A, SCN10A, and SCN11A, with female:male gene ratios close to 0.5, while SCN1A, SCN2A, SCN3A, SCN8A, and SCN9A female:male gene ratios were close to 1.0 (Fig. 1b). Sex differences in copy number were analyzed using unpaired t-tests of delta Ct values (CtSCN − Cteef1a1). Males and females differed in copy number for all putative Z-linked genes (p < 0.05, SCN4A, SCN5A, SCN10A, SCN11A, GH1, and TANC2) but did not differ for putative autosomal genes (p > 0.2, SCN1A, SCN2A, SCN3A, SCN8A, and SCN9A).

To confirm that this genomic structure also persists throughout the range of sympatry of T. sirtalis and Taricha, we measured relative copy numbers of Z-linked genes SCN4A and TANC2, as well as the autosomal gene SCN9A, from an additional four pairs of female and male snakes. One pair was sampled from each of four populations surveyed by Hague et al. (2017): Angelo (CA), Hopland (CA), Ten Mile (OR), and Cook Creek (WA). These populations include snakes with and without TTX-resistant mutations. Average female:male gene copy number ratios were similar across all five T. sirtalis populations tested, with median values of 0.508 for SCN4A, 0.528 for the Z-linked control TANC2, and 1.05 for the autosomal gene SCN9A. Paired t-tests indicated significant sex differences in copy number (delta Ct) for SCN4A (p = 0.001) and TANC2 (p < 0.0001) but not SCN9A (p = 0.701, Fig. 2), indicating that female garter snakes are hemizygous at the SCN4A locus throughout the western United States.

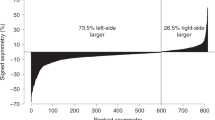

Copy number ratios for autosomal gene SCN9A, putative sex-linked gene SCN4A, and sex-linked gene TANC2, based on qPCR of genomic DNA from five pairs of females and males sampled from different populations in the western United States. Solid black bars indicate median ratios for the five populations. Black dotted lines indicate the expected female:male ratios for autosomal and sex-linked genes (1.0 and 0.5, respectively).

Female hemizygosity accounts for most Hardy–Weinberg disequilibrium in T. sirtalis populations

Our finding that female garter snakes are hemizygous for SCN4A led us to conclude that females were incorrectly categorized as homozygotes in Hague et al. (2017), which may have affected estimates of allele frequency and expected heterozygosity within populations. We recalculated these values in light of this new information and tested whether sex linkage could account for the unusual deficiency of heterozygotes. Because of limited DNA availability, we were unable to reanalyze the exact individuals sampled by Hague et al. (2017). Instead, we sampled 270 snakes from 16 different populations in western North America (Table 3 and Fig. 3), including many of same locations sampled by Hague et al. (2017). We verified the sex of each animal using sex-specific PCR primers and confirmed that our sample comprised 124 males and 146 females (Table 3). We also genotyped each snake for the amino acid sequence in the DIV p-loop of the Nav1.4 channel. Methods for Sanger sequencing are described in Hague et al. (2017). Briefly, for each individual, we sequenced a 666-bp fragment of SCN4A that includes the DIV p-loop region of Nav1.4. Heterozygous positions on chromatograms were identified by eye using Geneious version 6.1.8 (Kearse et al. 2012) and confirmed in both directions with sequencing. The haplotype phase of the DIV p-loop sequence for each individual was inferred computationally with the program PHASE (Stephens et al. 2001). We then translated the aligned DIV p-loop coding sequences into amino acids using Mesquite version 3.11 (Maddison and Maddison 2016) for subsequent analyses of HWE.

a Schematic of the Nav1.4 skeletal muscle sodium ion channel in T. sirtalis. Each domain (DI–DIV) is shown with the extracellular pore loops (p-loops) highlighted with bold lines. Specific amino acid changes in the DIV p-loop are shown in their relative positions within the pore. Below, the TTX-sensitive ancestral sequence (purple) is listed, followed by derived alleles that are known to confer stepwise increases in channel resistance; V (blue), VA (orange), LVNV (red). b Pie charts indicate the observed population frequencies of the four DIV alleles, while accounting for female hemizygosity. Chart size is proportional to sample size. On the map background, population-level average phenotypic TTX resistance (50% MAMU) of T. sirtalis is interpolated across the geographic range of sympatry with Taricha newts. c To visualize joint deviations from HWE/EAF in the southern part of our sampling range, sex-specific genotypes are indicated for each individual surveyed from the four polymorphic California populations (Willits, Knoxville, Russian River, and Ledson Marsh). Deviations from HWE/EAF are indicated by asterisks. Each individual is represented by a square, and fill colors indicate the alleles present within each individual (two alleles for males and one for hemizygous females). Figure adapted from Hague et al. (2017).

Because previous work has treated SCN4A as an autosomal locus (Feldman et al. 2010; Hague et al. 2017), we first replicated past analyses and assessed HWE while treating both males and females as diploid. We tested for significant deviations from HWE in the DIV p-loop using an exact test with the HWTriExact function in the R package HardyWeinberg (Graffelman and Camarena 2008; Graffelman 2015; R Development Core Team 2018). We also estimated observed heterozygosity (HO) and expected heterozygosity (HE) in the R package adegenet (Jombart and Ahmed 2011).

Next, we retested for deviations from HWE while accounting for sex linkage. Of the 270 individuals in our sample, all 28 heterozygotes were male, which is strongly consistent with the conclusion that females are hemizygous due to SCN4A sex linkage. Standard autosomal tests for HWE rely on the assumption of equality of allele frequencies (EAF) in males and females. If male and female allele frequencies differ dramatically, then the locus may not be in HWE. Graffelman and Weir (2016) propose an omnibus test that accounts for the hemizygous sex and simultaneously tests for deviations from HWE and EAF (Graffelman and Weir 2016, 2018a, 2018b). We conducted joint tests for departures from HWE and EAF with the HWTriExact function in the HardyWeinberg package in R. We also recalculated HO and HE in only males, the homogametic sex. Although recent work has provided a Bayesian approach to distinguish between deviations from HWE and EAF (Puig et al. 2019), this method is currently available only for biallelic loci, and so we do not use it here.

Population variation in TTX-resistant alleles of the DIV p-loop of SCN4A was consistent with population patterns of phenotypic TTX resistance from past work (Brodie et al. 2002; Hague et al. 2017). When we initially coded both males and females as diploid, most populations deviated significantly from HWE due to a deficiency of heterozygotes (Table 4), the same pattern observed in Hague et al. (2017). This pattern almost entirely disappeared when females were coded as hemizygous in the joint test for HWE and EAF. Moreover, we no longer detected the consistent pattern of heterozygote deficiency. However, two populations (Russian River and Ledson Marsh) deviated significantly from expectations of HWE and EAF (Table 4 and Fig. 3c). Although we were unable to test separately for deviations from HWE and EAF, inspection suggests that sex differences in allele frequency likely accounts for the majority of this deviation (Table 4 and Fig. 3c).

Discussion

Here, we provide evidence that nearly half of the voltage-gated sodium channel genes (SCN loci) are Z-linked in T. sirtalis and other colubroid snakes. This Z-linkage appears to date to the origin of the snake Z chromosome, which is homologous to Anolis autosome 6. Importantly, the skeletal muscle sodium channel gene SCN4A, which plays a major role in determining TTX resistance in T. sirtalis (Geffeney et al. 2005; Feldman et al. 2010; Hague et al. 2017), is among these sex-linked loci. Thus, female garter snakes are hemizygous at SCN4A. In contrast to previous studies assuming autosomal inheritance (Feldman et al. 2010; Hague et al. 2017), our reanalysis of population variation in SCN4A alleles found that most populations did not deviate from HWE and showed equal allele frequencies in the two sexes. These results demonstrate how cryptic hemizygosity can provide misleading results and emphasize the importance of considering sex linkage in population genetic surveys. We found that the two southernmost populations in our study (Russian River and Ledson Marsh) showed significant deviations from equilibrium predictions, likely because the sexes differed in allele frequency. In both populations, the highly TTX-resistant LVNV allele was found at higher frequencies in female snakes. Taken together, our results indicate that sex linkage is likely to play a critical role in the evolution of TTX resistance in garter snakes and raise the possibility that selection for resistance may occasionally be sexually antagonistic.

Sex linkage may have profound implications for microevolutionary change (reviewed in Johnson and Lachance (2012)). In general, X- and Z-linked genes show a pattern of more rapid evolution relative to autosomal genes (Vicoso and Charlesworth 2006, 2009; Zhang et al. 2014), and sex-linked genes are predicted to have outsized importance in local adaptation (Lasne et al. 2017). Several evolutionary processes have been implicated as drivers behind this “fast X” or “fast Z” evolution, including a stronger effect of drift due to a lower effective population size of sex chromosomes (Vicoso and Charlesworth 2009; Wright et al. 2015), a higher mutation rate in male-biased Z (and Y) chromosomes due to a high number of cell divisions during spermatogenesis (Haldane 1935; Miyata et al. 1987; Kirkpatrick and Hall 2004), stronger efficacy of selection in hemizygous individuals (Haldane 1924; Charlesworth et al. 1987; Mank et al. 2007; Singh et al. 2008; Sackton et al. 2014), and sex-biased migration (Lasne et al. 2017). Although selection driven by the consumption of toxic newts likely remains the most important ultimate cause of the evolution of extreme TTX resistance in garter snakes, the presence of SCN4A on the Z chromosome provides favorable genetic conditions for a rapid response to selection. The substitution rate of new beneficial Z-linked mutations can be substantially higher than that of autosomal mutations, particularly if the mutation rate is male-biased, or when mutations are recessive to some degree (Kirkpatrick and Hall 2004). A higher substitution rate for Z-linked mutations may be at least partially responsible for the repeated origins of TTX-resistant substitutions in SCN4A both within T. sirtalis (Hague et al. 2017) and across snake species (Feldman et al. 2012).

Sex linkage is also predicted to have consequences for the evolution of alleles with sexually antagonistic fitness effects (Rice 1984; Johnson and Lachance 2012). Under some conditions, sex linkage can facilitate the invasion of sexually antagonistic mutations, even when the fitness cost to one sex is substantially greater than the benefit to the other (Rice 1984). At least in some populations, TTX resistance experiences conflicting selection pressures, and it is possible that the balance of these costs and benefits affect the sexes differently. In the southern part of the range of overlap between T. sirtalis and toxic newts, the LVNV allele provides extreme resistance to TTX (Geffeney et al. 2005; Feldman et al. 2010; Hague et al. 2017), but also imposes a physiological cost of reduced channel function (Geffeney et al. 2005; Hague et al. 2018) and slower crawl speed in the absence of TTX (Brodie and Brodie 1999; Hague et al. 2018).

Anecdotal observations suggest that net selection favoring TTX resistance may be stronger in females than in males. In the wild, adult newts have been found exclusively in the guts of adult females (EDB III, pers. obs.). This trend is likely due to the female-biased sexual size dimorphism of garter snakes (Rossman et al. 1996); the smaller adult males are unlikely to be large enough to consume an adult newt. If females are indeed more likely to consume newts, then selection may favor the LVNV allele in females because of its effects on resistance. Conversely, the fitness cost of reduced speed is likely to lead to net selection against this allele in males. Further work in California T. sirtalis populations is necessary to test this hypothesis.

Although our interpretation is limited by our small sample sizes, sex differences in allele frequencies observed in the southernmost populations in our sample (Russian River and Ledson Marsh, Fig. 3, Tables 3 and 4) are consistent with such sexually antagonistic selection pressures on SCN4A. In the Russian River population, all females we sampled possessed the LVNV allele, whereas all but one male was homozygous for the nonresistant allele (Fig. 3 and Table 3). The LVNV allele was less common in the nearby Ledson Marsh population but was detected exclusively in females. In contrast, the moderately resistant V allele was found at a higher frequency in males. We did not detect a significant sex difference in the frequency of LVNV in the Knoxville population, where its frequency is much higher, or in the Willits population, where it is rare. If corroborated by larger samples, the sex differences in Russian River and Ledson Marsh would suggest that the ongoing coevolutionary arms race in these populations is driven primarily by selection on females. Sex differences in allele frequencies, as well as polymorphism itself, may be also be maintained by gene flow from neighboring populations. Dispersal has been shown to be male-biased in some species of snakes (Rivera et al. 2006; Keogh et al. 2007; Dubey et al. 2008; Pernetta et al. 2011; Hofmann et al. 2012), suggesting that males from neighboring populations may bring diverse SCN4A alleles into polymorphic populations like Russian River. The high homozygosity of males in that population is consistent with recent immigration of males, but this observation would need to be substantiated by a study with a larger sample size and wider genomic coverage.

The clear link between SCN4A mutations and TTX resistance (Geffeney et al. 2005; Feldman et al. 2010) and observations of multiple, independent origins of resistance in garter snake populations (Feldman et al. 2009, 2010; Hague et al. 2017) make TTX resistance an ideal system for studying molecular adaptation and convergent evolution. Our discovery of the Z-linkage of SCN4A in garter snakes provides an opportunity to investigate how sex linkage can alter the evolutionary trajectory of an adaptive trait. The transition of SCN4A from an autosome to a sex chromosome in a garter snake ancestor may have been a crucial step in their evolution of full-body TTX resistance, possibly by increasing substitution rates at this locus, maintaining costly resistance alleles, and altering the efficacy of selection on hemizygous females encountering toxic newts.

Data availability

DNA sequences collected for this study are deposited in the NCBI PopSet database with accession numbers MT043460 - MT043727. qPCR and genotype data can be found at https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.x95x69pf1.

References

Alföldi J, Di Palma F, Grabherr M, Williams C, Kong LS, Mauceli E et al. (2011) The genome of the green anole lizard and a comparative analysis with birds and mammals. Nature 477(7366):587–591

Bennani-Baiti IM, Jones BK, Liebhaber SA, Cooke NE (1995) Physical linkage of the human growth hormone gene cluster and the skeletal muscle sodium channel alpha-subunit gene (SCN4A) on chromosome 17. Genomics 29(3):647–652

Brodie III ED, Brodie Jr ED (1990) Tetrodotoxin resistance in garter snakes: an evolutionary response of predators to dangerous prey. Evolution 44(3):651–659

Brodie III ED, Brodie Jr ED (1999) Costs of exploiting poisonous prey: evolutionary trade-offs in a predator-prey arms rage. Evolution 53(2):626–631

Brodie III ED, Brodie Jr ED (2015) Predictably convergent evolution of sodium channels in the arms race between predators and prey. Brain Behav Evol 86(1):48–57

Brodie Jr ED (1968) Investigations on the skin toxin of the adult rough-skinned newt, Taricha granulosa. Copeia 1968(2):307–313

Brodie Jr ED, Ridenhour BJ, Brodie III ED (2002) The evolutionary response of predators to dangerous prey: hotspots and coldspots in the geographic mosaic of coevolution between garter snakes and newts. Evolution 56(10):2067–2082

Charlesworth B, Coyne JA, Barton NH (1987) The relative rates of evolution of sex chromosomes and autosomes. Am Nat 130(1):113–146

Crow JF, Kimura M (1970) An introduction to population genetics theory. Harper & Row, Publishers, New York, NY

Dubey S, Brown GP, Madsen T, Shine R (2008) Male-biased dispersal in a tropical Australian snake (Stegonotus cucullatus, Colubridae). Mol Ecol 17(15):3506–3514

Feldman CR, Brodie Jr ED, Brodie III ED, Pfrender ME (2009) The evolutionary origins of beneficial alleles during the repeated adaptation of garter snakes to deadly prey. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106(32):13415–13420

Feldman CR, Brodie Jr ED, Brodie III ED, Pfrender ME (2010) Genetic architecture of a feeding adaptation: garter snake (Thamnophis) resistance to tetrodotoxin bearing prey. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 277(1698):3317–3325

Feldman CR, Brodie Jr ED, Brodie III ED, Pfrender ME (2012) Constraint shapes convergence in tetrodotoxin-resistant sodium channels of snakes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109(12):4556–4561

Fozzard HA, Lipkind GM (2010) The tetrodotoxin binding site is within the outer vestibule of the sodium channel. Mar Drugs 8(2):219–234

Geffeney SL, Fujimoto E, Brodie III ED, Brodie Jr ED, Ruben PC (2005) Evolutionary diversification of TTX-resistant sodium channels in a predator-prey interaction. Nature 434(7034):759–763

Graffelman J (2015) Exploring diallelic genetic markers: the HardyWeinberg package. J Stat Softw 64:1–23

Graffelman J, Camarena JM (2008) Graphical tests for Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium based on the ternary plot. Hum Hered 65(2):77–84

Graffelman J, Weir BS (2016) Testing for Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium at biallelic genetic markers on the X chromosome. Heredity 116(6):558–568

Graffelman J, Weir BS (2018a) Multi-allelic exact tests for Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium that account for gender. Mol Ecol Resour 18(3):461–473

Graffelman J, Weir BS (2018b) On the testing of Hardy-Weinberg proportions and equality of allele frequencies in males and females at biallelic genetic markers. Genet Epidemiol 42(1):34–48

Hague MTJ, Feldman CR, Brodie Jr ED, Brodie III ED (2017) Convergent adaptation to dangerous prey proceeds through the same first-step mutation in the garter snake Thamnophis sirtalis. Evolution 71(6):1504–1518

Hague MTJ, Toledo G, Geffeney SL, Hanifin CT, Brodie Jr ED, Brodie III ED (2018) Large-effect mutations generate trade-off between predatory and locomotor ability during arms race coevolution with deadly prey. Evol Lett 2(4):406–416

Haldane JBS (1924) A mathematical theory of natural and artificial selection—I. B Math Biol 52(1):209–240

Haldane JBS (1935) The rate of spontaneous mutation of a human gene. J Genet 83(3):235–244

Hanifin CT, Brodie Jr ED, Brodie III ED (2008) Phenotypic mismatches reveal escape from arms-race coevolution. PLOS Biol 6(3):471–482

Hanifin CT, Yotsu-Yamashita M, Yasumoto T, Brodie III ED, Brodie Jr ED (1999) Toxicity of dangerous prey: variation of tetrodotoxin levels within and among populations of the newt Taricha granulosa. J Chem Ecol 25(9):2161–2175

Hillier LW, Miller W, Birney E, Warren W, Hardison RC, Ponting CP et al. (2004) Sequence and comparative analysis of the chicken genome provide unique perspectives on vertebrate evolution. Nature 432(7018):695–716

Hofmann S, Fritzsche P, Solhøy T, Dorge T, Miehe G (2012) Evidence of sex-biased dispersal in Thermophis baileyi inferred from microsatellite markers. Herpetologica 68(4):514–522

Johnson NA, Lachance J (2012) The genetics of sex chromosomes: evolution and implications for hybrid incompatibility. Ann NY Acad Sci 1256:E1–E22

Jombart T, Ahmed I (2011) adegenet 1.3-1: New tools for the analysis of genome-wide SNP data. Bioinformatics 27(21):3070–3071

Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, Sturrock S et al. (2012) Geneious Basic: An integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 28(12):1647–1649

Keogh JS, Webb JK, Shine R (2007) Spatial genetic analysis and long-term mark-recapture data demonstrate male-biased dispersal in a snake. Biol Lett 3(1):33–35

Kirkpatrick M, Hall DW (2004) Male-biased mutation, sex linkage, and the rate of adaptive evolution. Evolution 58(2):437–440

Lachance J (2009) Detecting selection-induced departures from Hardy–Weinberg proportions. Genet Sel Evol 41:15

Laopichienpong N, Tawichasri P, Chanhome L, Phatcharakullawarawat R, Singchat W, Kantachumpoo A et al. (2017) A novel method of caenophidian snake sex identification using molecular markers based on two gametologous genes. Ecol Evol 7(13):4661–4669

Lasne C, Sgro CM, Connallon T (2017) The relative contributions of the X chromosome and autosomes to local adaptation. Genetics 205(3):1285–1304

Maddison WP, Maddison DR. (2016) Mesquite: a modular system for evolutionary analysis. Version 3.11. http://mesquiteproject.org

Mank JE, Axelsson E, Ellegren H (2007) Fast-X on the Z: rapid evolution of sex-linked genes in birds. Genome Res 17(5):618–624

McGlothlin JW, Kobiela ME, Feldman CR, Castoe TA, Vonk FJ, Richardson MK et al. (2016) Historical contingency in a multigene family facilitates adaptive evolution of toxin resistance. Curr Biol 26:1616–1621

Miyata T, Hayashida H, Kuma K, Mitsuyasu K, Yasunaga T (1987) Male-driven molecular evolution: a model and nucleotide sequence analysis. Cold Spring Harb Sym 52:863–867

Moreno-Hagelsieb G, Latimer K (2007) Choosing BLAST options for better detection of orthologs as reciprocal best hits. Bioinformatics 24(3):319–324

Pernetta AP, Allen JA, Beebee TJC, Reading CJ (2011) Fine-scale population genetic structure and sex-biased dispersal in the smooth snake (Coronella austriaca) in southern England. Heredity 107(3):231–238

Perry BW, Card DC, McGlothlin JW, Pasquesi GIM, Adams RH, Schield DR et al. (2018) Molecular adaptations for sensing and securing prey and insight into amniote genome diversity from the garter snake genome. Genome Biol Evol 10(8):2110–2129

Pfaffl MW (2001) A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res 29(9):e45

Pokorná M, Kratochvíl L (2009) Phylogeny of sex-determining mechanisms in squamate reptiles: are sex chromosomes an evolutionary trap? Zool J Linn Soc-Lond 156(1):168–183

Puig X, Ginebra J, Graffelman J (2019) Bayesian model selection for the study of Hardy–Weinberg proportions and homogeneity of gender allele frequencies. Heredity 123(5):549–564

R Development Core Team (2018) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. http://R-project.org

Rice WR (1984) Sex chromosomes and the evolution of sexual dimorphism. Evolution 38(4):735–742

Rivera PC, Gardenal CN, Chiaraviglio M (2006) Sex-biased dispersal and high levels of gene flow among local populations in the argentine boa constrictor, Boa constrictor occidentalis. Austral Ecol 31(8):948–955

Rossman DA, Ford NB, Seigel RA (1996) The garter snakes: evolution and ecology. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, OK

Rovatsos M, Vukić J, Lymberakis P, Kratochvíl L (2015) Evolutionary stability of sex chromosomes in snakes. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 282(1821):20151992

Sackton TB, Corbett-Detig RB, Nagaraju J, Vaishna L, Arunkumar KP, Hartl DL (2014) Positive selection drives faster-Z evolution in silkmoths. Evolution 68(8):2331–2342

Schield DR, Card DC, Hales NR, Perry BW, Pasquesi GM, Blackmon H et al. (2019) The origins and evolution of chromosomes, dosage compensation, and mechanisms underlying venom regulation in snakes. Genome Res 29(4):590–601

Singh ND, Larracuente AM, Clark AG (2008) Contrasting the efficacy of selection on the X and autosomes in Drosophila. Mol Biol Evol 25(2):454–467

Stephens M, Smith NJ, Donnelly P (2001) A new statistical method for haplotype reconstruction from population data. Am J Hum Genet 68(4):978–989

Untergasser A, Cutcutache I, Koressaar T, Ye J, Faircloth BC, Remm M et al. (2012) Primer3-new capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res 40(15):e115

Vicoso B, Charlesworth B (2006) Evolution on the X chromosome: unusual patterns and processes. Nat Rev Genet 7(8):645–653

Vicoso B, Charlesworth B (2009) Effective population size and the faster-X effect: an extended model. Evolution 63(9):2413–2426

Vicoso B, Emerson JJ, Zektser Y, Mahajan S, Bachtrog D (2013) Comparative sex chromosome genomics in snakes: differentiation, evolutionary strata, and lack of global dosage compensation. PLoS Biol 11(8):e1001643

Wickham H (2009) ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. Springer, New York, NY

Wright AE, Harrison PW, Zimmer F, Montgomery SH, Pointer MA, Mank JE (2015) Variation in promiscuity and sexual selection drives avian rate of faster-Z evolution. Mol Ecol 24(6):1218–1235

Ye J, Coulouris G, Zaretskaya I, Cutcutache I, Rozen S, Madden TL (2012) Primer-BLAST: a tool to design target-specific primers for polymerase chain reaction. BMC Bioinforma 13:134

Zakon HH, Jost MC, Lu Y (2011) Expansion of voltage-dependent Na+ channel gene family in early tetrapods coincided with the emergence of terrestriality and increased brain complexity. Mol Biol Evol 28(4):1415–1424

Zhang GJ, Li C, Li QY, Li B, Larkin DM, Lee C et al. (2014) Comparative genomics reveals insights into avian genome evolution and adaptation. Science 346(6215):1311–1320

Zheng YC, Wiens JJ (2016) Combining phylogenomic and supermatrix approaches, and a time-calibrated phylogeny for squamate reptiles (lizards and snakes) based on 52 genes and 4162 species. Mol Phylogenet Evol 94:537–547

Acknowledgements

We thank Drew Schield, Blair Perry, and Todd Castoe for providing an early draft of the C. viridis genome. We are grateful to Caitlin McCaughan and Mercedes Collins for lab assistance and T. St. Pierre for field assistance. We thank the Departments of Fish and Wildlife in Washington, Oregon, and California for scientific collecting permits to MTJH (WA: 18-082, OR: 063-18, and CA: SC-11937) and CRF (CA: SC-000814). We also thank the California Department of Parks and Recreation, Hopland Research and Extension Center, the UC Natural Reserve System, and Sonoma Mountain Ranch. All procedures involving animals were approved by the UNR (protocol 00687) and USU (protocol 1008) IACUCs. This work was supported by a Doctoral Dissertation Improvement Grant from the National Science Foundation to MTJH and EDB III (DEB 1601296), by an RC Lewontin Award from the Society for the Study of Evolution to KLG, and by NSF support to EDB III (DEB 0922251), to CRF (IOS 1355221), and to JWM (DEB 1457463).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Associate editor: Aurora Ruiz-Herrera

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gendreau, K.L., Hague, M.T.J., Feldman, C.R. et al. Sex linkage of the skeletal muscle sodium channel gene (SCN4A) explains apparent deviations from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium of tetrodotoxin-resistance alleles in garter snakes (Thamnophis sirtalis). Heredity 124, 647–657 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41437-020-0300-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41437-020-0300-5