Abstract

Purpose

Missing heritability in human diseases represents a major challenge, and this is particularly true for ABCA4-associated Stargardt disease (STGD1). We aimed to elucidate the genomic and transcriptomic variation in 1054 unsolved STGD and STGD-like probands.

Methods

Sequencing of the complete 128-kb ABCA4 gene was performed using single-molecule molecular inversion probes (smMIPs), based on a semiautomated and cost-effective method. Structural variants (SVs) were identified using relative read coverage analyses and putative splice defects were studied using in vitro assays.

Results

In 448 biallelic probands 14 known and 13 novel deep-intronic variants were found, resulting in pseudoexon (PE) insertions or exon elongations in 105 alleles. Intriguingly, intron 13 variants c.1938-621G>A and c.1938-514G>A resulted in dual PE insertions consisting of the same upstream, but different downstream PEs. The intron 44 variant c.6148-84A>T resulted in two PE insertions and flanking exon deletions. Eleven distinct large deletions were found, two of which contained small inverted segments. Uniparental isodisomy of chromosome 1 was identified in one proband.

Conclusion

Deep sequencing of ABCA4 and midigene-based splice assays allowed the identification of SVs and causal deep-intronic variants in 25% of biallelic STGD1 cases, which represents a model study that can be applied to other inherited diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

High-throughput genome sequencing has made a huge impact in biology and is considered the most powerful genetic test to elucidate inherited human diseases.1 It allows the unbiased detection of a wide spectrum of genetic variants including coding and noncoding single-nucleotide variants (SNVs), as well as structural variants (SVs). However, sequencing and data storage costs as well as the possibility of secondary genetic findings hamper the use of genome sequencing.

Based on the advantages and limitations mentioned above, genome sequencing is not the best method to perform sequence analysis of one or a few genes that are associated with a clinically distinct condition. This is illustrated by autosomal recessive Stargardt disease (STGD1), which is caused by variants in the ABCA4 gene. STGD1 is the most frequently inherited macular dystrophy with an estimated prevalence of 1/10,000.2 Thus far, 1180 unique ABCA4 variants have been reported in 8777 alleles of 6684 cases (www.lovd.nl/ABCA4).3 A large proportion of the variants affect noncanonical splice site (NCSS) sequences, with variable effects on messenger RNA (mRNA) processing,4,5,6 and several deep-intronic (DI) variants have been identified.5,7,8,9,10,11,12,13 Most of these DI variants strengthen cryptic splice sites resulting in the insertion of pseudoexons (PEs) in the mature ABCA4 mRNA. SVs seem to be rare in ABCA4,7,10,12,14 although systematic copy-number variant (CNV) analyses have not been performed in most STGD1 cases.

Due to the relatively large size of the ABCA4 gene (50 exons; 128,313 bp), variant screening initially was restricted to the scanning of the exons and flanking splice sites with poor sensitivity, leaving 50–70% of STGD1 probands genetically unsolved.14,15,16,17 Recently, sequence analysis of the entire 128-kb gene was performed using next-generation sequencing platforms using Raindance microdroplet polymerase chain reaction (PCR) target enrichment or Illumina TruSeq Custom Amplicon target enrichment,10 HaloPlex-based sequence enrichment,7,9 or genome sequencing.1,9

Identification of two pathogenic alleles is important to confirm the clinical diagnosis because several promising clinical trials are underway based on RNA modulation with antisense oligonucleotides,7,9,18 drug based therapies,19 as well as gene augmentation20 and stem cell therapies.21 STGD1 cases will only be eligible for these therapies if both causal alleles are known. In addition, recent studies identified alleles carrying a coding variant in cis with a DI variant, and only these combinations represented fully penetrant alleles,7,9 pointing toward the importance of analyzing noncoding regions in the STGD1 cases.

Recently, we reported on the use of 483 single-molecule molecular inversion probes (smMIPs) to sequence the 50 exons and 12 intronic regions carrying 11 pathogenic DI variants of 412 genetically unsolved STGD1 cases.5 In this study, we aimed to design a semiautomated, high-throughput, cost-effective, and comprehensive sequence analysis of the entire ABCA4 gene, which could serve as a model study to investigate human inherited diseases due to variants in one or a few genes. Using 3866 smMIPs we sequenced 1054 genetically unsolved STGD or STGD-like probands and 138 biallelic controls carrying known ABCA4 variants. Novel NCSS and DI variants were tested in vitro for splice defects. Additionally, a very high and reproducible read coverage allowed us to perform CNV analysis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Samples

Twenty-one international and four national centers ascertained 1054 genetically unsolved probands in whom STGD was part of the differential diagnosis as determined by the local ophthalmologists specializing in inherited retinal diseases. Since ABCA4 disease is known for its clinical heterogeneity, a spectrum of (overlapping) ABCA4-associated phenotypes were part of this study, as well as a STGD1 phenocopy: central areolar choroidal dystrophy (CACD). The clinical findings specific to a certain clinical diagnosis and the main phenotypic characteristics used in the differential diagnosis are described in Table S1. Also, 19 cases with a clinical diagnosis of macular dystrophy without further specification were included.

Among 1054 cases 833 probands were previously screened by employing different screening methods, i.e., exome sequencing, targeted gene panel sequencing including all ABCA4 coding regions, and Sanger sequencing of all coding ABCA4 exons. Details are provided in Table S2.

We discerned two patient groups. The first patient group consisted of 993 genetically unsolved probands who carried one (n = 345) or no (n = 648) ABCA4 allele. For two subjects, DNA was not available and both parents of the probands were studied, assuming autosomal recessive inheritance. The second patient group consisted of 61 “partially solved” probands, carrying the c.5603A>T (p.Asn1868Ile) variant in trans with other alleles. This last group was also investigated as it was suspected that there could be unidentified DI variants in cis with c.5603A>T, as the penetrance of c.5603A>T, when in trans with a severe ABCA4 variant, was ~5% in the population.22,23

This study was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee 2010-359 (Protocol nr. 2009-32; NL nr. 34152.078.10) and the Commissie Mensgebonden Onderzoek Arnhem-Nijmegen (Dossier no. 2015-1543; dossier code sRP4h). All samples were collected according to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and written informed consent was obtained for all patients participating in the study.

smMIPs design and ABCA4 sequence analysis

Detailed information on the smMIPs-based ABCA4 sequencing, selection of candidate splice variants, and inclusion criteria is provided in the Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Midigene-based splice assay

The effect of nine NCSS variants and 58 DI variants was assessed by midigene-based splicing assays employing 23 wild-type (WT) BA clones previously described4 and the newly designed BA32, BA33, BA34, and BA35. WT and mutant constructs were transfected in HEK293T cells and the extracted total RNA was subjected to reverse transcription (RT)-PCR as described previously.4 Details are provided in Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Identification of CNVs and assessment of the underlying mechanism

An Excel-based script was employed to detect CNVs using smMIP read number. Microhomology at the breakpoints was assessed using ClustalW, breakpoint regions were analyzed for non-B motifs by tool (nBMST and QGRS Mapper) (for details see Supplementary Materials and Methods).

Semiquantification of RT-PCR products

To quantify the ratios between correct and aberrant RT-PCR products, densitometric analysis was performed using ImageJ software.

Uniparental disomy detection

To test the presence of uniparental disomy (UPD), haplotype analysis was performed in one STGD1 case (DNA14-33085) using exome sequencing data.

RESULTS

smMIPs performance and ABCA4 sequencing

A pilot sequencing study was conducted using 15 STGD1 samples and five DNA samples of control individuals, revealing all 34 previously identified variants (Table S3). The average number of reads for the 20 DNA samples ranged from 10 to 152,500 per smMIP, with an overall average coverage of 933× for each smMIP.

In total 1192 DNA samples were analyzed for variants in ABCA4 using six NextSeq500 runs. The average number of reads of the 3866 smMIPs was 377×. As most nucleotide positions are targeted with two smMIPs, the effective average coverage was ~700×. To determine the coverage of ABCA4 in more detail, we calculated the average coverage of each nucleotide position for runs 1 to 5 combined (Table S4). To visualize the results, nucleotide positions that were not covered or poorly covered (≤10 reads), moderately covered (11–49 reads), or well covered (≥50 reads) are depicted in Fig. S1. From the 128,366 nt of ABCA4, 1980 nt (1.5%) were not or poorly covered, 1410 nt (1.1%) were moderately covered, and 124,976 nt (97.4%) were well covered. Although ABCA4 introns carry several repetitive elements (Fig. S1), they only had a small effect on smMIPs design. Several larger repeats are present in up- and downstream regions of ABCA4, which resulted in the absence—or poor performance—of smMIPs. Sequencing of 1192 samples yielded a total of 7756 unique ABCA4 variants that are listed in Table S5.

Sensitivity and specificity of the smMIPs-based sequencing

To assess the sensitivity of the new smMIPs sequencing platform, we tested 123 previously genotyped samples5,9 in three series (runs 2, 3, and 6) (Table S6) as well as 15 control DNA samples carrying 13 different SVs spread throughout the ABCA4 gene (run 6) (Table S7). All previously known SNVs (n = 300) and 13 SVs could be identified, yielding a sensitivity of 100%. Six additional variants were found due to low coverage in the previous studies, and three variants had not been annotated correctly previously.

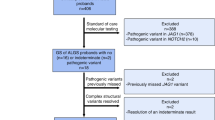

ABCA4 gene sequencing and identification of variants

ABCA4 sequencing was performed for 1054 genetically unsolved STGD and STGD-like patients. This revealed 323 unique (likely) pathogenic SNVs and 11 SVs in 1144 alleles. Sixty-four of 323 SNVs (26%) and all 11 SVs were novel (Table S8). Detailed in silico analysis of novel SNVs is provided in Table S9. Thirteen percent of these alleles were represented by DI variants and SVs and another 10% accounted for NCSS variants (Fig. 1a). All variants and the respective cases were uploaded into the ABCA4 variant and STGD1 cases database LOVD at www.lovd.nl/ABCA4.

a The contribution of each type of variant or allele in biallelic and monoallelic cases except those carrying c.5603A>T is represented. Protein truncating variants comprise nonsense, frameshift, and canonical splice site variants. The 10% complex alleles only consist of combinations of missense variants, the most frequent of which were c.[1622T>C;3113C>T] (n = 30; 27% of all complex alleles) and c.[4469G>A;5603A>T] (n = 27; 25% of all complex alleles). They do not include the complex alleles that contain noncanonical splice site (NCSS) variants, deep-intronic variants, or protein truncating variants, when present in cis with other variants. If these would have been included, 16% of the alleles would consist of complex alleles. b Deep-intronic variant allele count in this study. Novel deep-intronic variants are highlighted in red. One hundred seventeen causal deep-intronic variants were identified. The deep-intronic variants c.4539+2001G>A (n = 26) and c.4253+43G>A (n = 21) were found most frequently. Most of the novel deep-intronic variants were found in single STGD1 probands.

Two (likely) pathogenic variants were found in 323 probands, three probands carried p.Asn1868Ile in a homozygous manner, and one (likely) causal variant in trans with p.Asn1868Ile was found in 125 probands. Only one (likely) causal variant was identified in 174 probands. Additionally, in 65 probands, the p.Asn1868Ile variant was the only identified variant (Table S10). No (likely) causal variants were found in 364 cases.

Among the SNVs, the most common causal alleles were c.5603A>T (n = 134), c.5882G>A (n = 84), c.[5461-10T>C;5603A>T] (n = 44), c.[1622T>C;3113C>T] (n = 30), c.[4469G>A;5603A>T] (n = 27), c.4539+2001G>A (n = 26), c.6079C>T (n = 23), and c.4253+43G>A (n = 21) (Table S8). To visualize the relative frequency of causal STGD1-causing alleles, we excluded 65 heterozygous c.5603A>T alleles that were found as the only ABCA4 allele in these cases, as they were most likely present because of its high allele frequency (0.06) in the general population (Fig. S2).23,24

Splice defects due to noncanonical splice site variants

The effect on splicing of nine NCSS variants was tested in nine wild-type splice constructs previously described4 (Fig. S3). All of the nine tested novel NCSS variants showed a splice defect when tested in HEK293T cells. Severity was assigned according to the percentage of remaining WT mRNA, as described previously.4 Five NCSS variants were deemed severe as they showed ≤30 of WT mRNA, three were considered to have a moderate effect with WT RNA present between >30 and ≤70% correct RNA and only one was mild as it showed >70% of WT RNA (Table S11, Fig. S4).

Deep-intronic variants identification and functional characterization

Based on the defined selection criteria, 58 DI variants were selected for splice assays. To test their effects, 27 WT midigene splice constructs were employed, 23 of which were described previously,4 and four of which were new (Fig. S3). Thirteen of 58 tested DI variants showed a splice defect upon RT-PCR and Sanger validation (Figs. 2 and 3). For the variants that did not show any splice defect, RT-PCR results are shown in Fig. S5.

Wild-type (WT) and mutant (MT) midigenes were transfected in HEK293T cells and the extracted RNA was subjected to reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Left panels show the ABCA4-specific RT-PCR products with Rhodopsin exon 5 (RHO e5) RT-PCR as a transfection efficiency control. In the middle panels, Sanger sequencing results of the RT-PCR products are given. At the right side, pseudoexons (PEs) and an exon elongation are depicted with splice site strength predictions for WT and MT sequences, with green rectangles representing the splice acceptor sites and blue rectangles representing the splice donor sites. Red highlighted nucleotides represent the variants. Except for c.1937+37C>G (e), which resulted in a 36-nt exon 13 elongation, all deep-intronic variants lead to PEs (a–d, f, g). The intron 7 variants in (d) result in partially overlapping PEs that share the same splice acceptor site at position c.859-685. HSF Human Splicing Finder, na not applicable, PE pseudoexon, SSFL splice site finder–like.

Six of the novel DI variants, i.e., variants c.570+1798A>G, c.769-788A>T, c.859-640A>G, c.1938-514A>G, c.2588-706C>T, and c.4634+741A>G, resulted in out-of-frame PE inclusions in the RNA and were deemed severe (Figs. 2 and 3). Variants c.67-2023T>G and c.859-546G>A were classified to have a moderate effect as 33% and 36% of the WT RNA products were present, respectively. As predicted due to the presence of a downstream cryptic splice donor site (SDS), variant c.1937+37C>G led to an elongation of exon 13 by 36 nucleotides, which resulted in the introduction of a premature stop codon (p.Phe647*). Moreover, two intron 13 variants, c.1938-621G>A and c.1938-514A>G, showed a complex splice pattern that led to the generation of two mutant transcripts each (Fig. 3a–c). Each of these products contained a shared PE of 134 nt (PE1) as well as variant-specific PEs, denoted PE2 (174 nt) or PE3 (109 nt) for c.1938-621G>A and c.1938-514A>G, respectively (Fig. S6). For variant c.1938-621G>A only 7% of the total complementary DNA (cDNA) product showed PE inclusion whereas for c.1938-514A>G, 87% of the cDNA products were mutant. To investigate the nature of the PE1 insertions, we studied the exon 12–17 segment of the mRNA obtained from photoreceptor progenitor cells (PPCs) derived from a control person. As depicted in Fig. S7, transcripts containing PE1 or PE1 and PE2 were identified when PPCs were grown under nonsense-mediated decay–suppressing conditions. The sum quantity of these two products was 2.9% of total mRNA suggesting that there are small amounts of PE insertions involving PE1 in the healthy retina.

a Genomic structure of intron 13 containing three pseudoexons (PEs) due to four deep-intronic variants. PE2 and PE3 share a splice donor site (SDS) (for PE2) and splice acceptor site (for PE3). Variants c.1938-621G>A and c.1938-619A>G strengthen the same cryptic SDS of PE2 slightly or strongly, respectively, as based on the Human Splicing Finder (HSF). Variant c.1938-514A>G creates a new strong SDS of PE3. The canonical and putative canonical splice sequences are given in bold lettering. The first and last positions of the PEs are provided. b Agarose gel analysis of reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) products for intron 13 variants upon HEK293T cell splice assays. PE2 and PE3 were observed as single insertions, but also in combination with PE1. #Heteroduplex fragments of the lower bands. c Schematic representation of all mutant transcripts identified upon RT-PCR in HEK293T cell splice assays and of PE1 and PE1/PE2 observed as naturally occurring PEs when analyzing photoreceptor progenitor cells (PPCs) derived from a healthy individual. Interestingly, PE1 was previously shown to be induced by variant c.1937+435C>G (*Sangermano et al.)9 and also can be part of mutant transcripts, together with PE2 or PE3. This is surprising as it is located far upstream of the other causal variants. **Reported by Fadaie et al.13 d Variant c.6148-84A>T strengthens a SDS and results in PE1a or PE1b by employing upstream or downstream splice acceptor sites, respectively. These splice acceptor sites are comparable in predicted strength based on HSF. The canonical splice sequences are given in bold. e Agarose gel analysis of RT-PCR products due to c.6148-84A>T. f The largest fragment shows a 173-nt PE insertion between exons 44 and 45. The second largest band contains a 221-nt PE insertion (PE1a) and skipping of exon 44. The third-largest fragment represents the WT messenger RNA (mRNA) and the smallest fragment misses exon 45. The relative amounts of the products are listed at the right side.

Intriguingly, DI variant c.6148-84A>T showed four RNA splice products, namely a normal spliced RNA, the skipping of exon 45, the insertion of a 221-nt PE (pe1a) coupled with the deletion of exon 44, and finally, the insertion of a 173-nt PE (pe1b) that consist of the same SDS as pe1a but a different splice acceptor site (SAS) (Fig. 3d–f). Finally, variant c.3863-1064A>G showed a complex splice pattern compared with the WT and variant c.6283-78G>T led to the insertion of a 203-nt PE in intron 45 (Fig. S6). However, the exact boundaries of the presumed PE for variant c.3863-1064A>G could not yet be determined due to technical difficulties.

Overall, 13 novel DI variants were found in 18 alleles. Next to the novel variants, 14 previously reported pathogenic DI variants7,8,9,13,18 were found in a total of 99 alleles, details of which are shown in Fig. 1b and Table S8.

Identification of novel structural variants in STGD1 cases

Among 1054 STGD and STGD-like patients analyzed, we identified 11 unique novel heterozygous SVs, all exon-spanning deletions, in 16 patients. The corresponding deletions encompass between 1 and 33 exons, ranging from 411 bp to 55.7 kb (Fig. 4, Tables S12–S17). All deletions were found in a heterozygous state in single cases, except the smallest (c.699_768+341del), which encompassed 70 bp of exon 6 and 341 bp of intron 6, and was found in six unrelated patients of Spanish origin. Deletion breakpoints were determined employing genomic PCR and Sanger sequencing for 9 of the 11 deletions. Two deletion junctions (deletions 7 and 11) could not be amplified as the 3’ breakpoints were located downstream of the gene beyond the regions targeted by smMIPs. Surprisingly, Sanger sequencing revealed two complex rearrangements as deletions 5 and 6 carried inverted fragments of 279 and 224 bp respectively, residing between large deletions. These small inversions could not be identified with the CNV detection tool.

Schematic representation of the 11 structural variants identified. Exons are represented as boxes, black when they are not deleted and gray when they are deleted. Introns are represented as continuous lines, whereas stippled lines depict the deleted regions. Question marks denote that the exact location of breakpoints were unknown. Inverted double arrows represent inverted sequences.

Microhomologies, repetitive elements, and non-B DNA conformation at deletion breakpoints

The breakpoints of the deletions were subjected to bioinformatic analysis to find elements underlying their formation. The presence of microhomology, repetitive elements, and non-B DNA conformations was investigated except for deletions 7 and 11 as exact boundaries could not be determined by Sanger sequencing. All other studied SVs presented microhomology at the breakpoint junctions, ranging in size from 1 to 6 bp (Fig. S8), four of which presented short insertions (Table S18). In 8 of 11 (72.7%) of the deletion breakpoints, a known repetitive element was observed, including seven non–long terminal repeats (non-LTR) retrotransposons, among which there were one short interspersed nuclear element (SINE) and four long interspersed nuclear elements (LINEs), three DNA transposons from the hAT superfamily, and two retrotransposons from the LTR superfamily. However, no breakpoint was part of a known element belonging to the same class and no Alu sequence was observed at the breakpoint junctions. Finally, the most prevalent non-B conformations observed among our breakpoints are Oligo(G)n tracts as 21 of these repeats were found in seven SVs (Tables S18, S19). Inverted repeats were observed in five breakpoint regions. No direct repeats or mirror repeats have been detected, therefore excluding triplex and slipped hairpin structure formation, respectively.

Uniparental isodisomy of chromosome 1

In STGD1 proband DNA14-33085, a causal homozygous DI variant, c.859-506G>C (p.[Phe287Thrfs*32,=]), was identified. Segregation analysis revealed this variant to be present in his unaffected father, but not in his unaffected mother. To test the possibility that the mother carried a deletion spanning this variant, we performed CNV analysis in the proband’s ABCA4 gene. No deletion was identified (Table S17, column AU) and no heterozygous SNPs were observed in or near ABCA4 in the proband’s DNA. To test whether the chromosome 1 of the father carrying the c.859-506G>C ABCA4 variant was passed on to the proband as two copies (UPD), exome sequencing was conducted for the proband’s DNA. As shown in Fig. S9, chromosome 1 of the proband carries only homozygous SNPs, strongly suggesting the occurrence of UPD.

DISCUSSION

Employing 3866 smMIPs, 97.4% of the 128-kb ABCA4 gene could be sequenced robustly in 1054 genetically unsolved probands with a STGD or a STGD-like phenotype. In this way, 448 (42.5%) of the probands could be genetically solved. We not only identified nine novel NCSS variants and 13 novel DI variants, but also 11 novel heterozygous SVs. The large setup of this study allowed us to provide a “landscape” overview of the different variant types underlying STGD1. As depicted in Fig. 1a, we can appreciate that DI variants constitute a significant cause of STGD1, i.e., 11.7% of the alleles in biallelic cases, identified in 22.5% of biallelic probands. Deletions constitute 1.8% of alleles and were found in 3.5% of biallelic cases. Seven probands carried two DI variants or one DI variant and one SV. Taken together, “dark matter” alleles were found in 113/448 (25.2%) biallelic STGD1 probands. Together, these results strongly argue for a complete sequence analysis of the ABCA4 gene to fully appreciate its mutational landscape.

Complex splice defects due to intron 13 and 44 variants

Interestingly, the two intron 13 DI variants, i.e., c.1938-621G>A and c.1938-514G>A, were in close vicinity of two previously described variants, c.1937+435C>G9 and c.1938-619A>G.10,13 As shown in Fig. 3a–c the PE resulting from c.1937-514A>G (PE3) is located adjacent to PE2 as they share a dual SAS/SDS (Fig. 3a–c). The involvement of PE1, located 491, 493, and 775 nt upstream of variants c.1937-621G>A, c.1937-619A>G, and c.1937-514A>G, respectively, is very surprising. Control PPCs also show a small percentage (2.9%) of mRNAs containing PE1 or PE1–PE2. Interestingly, the SDS of PE1 also can be employed as a SAS, which, in theory could render this intronic SAS/SDS a target for recursive splicing.25 Together, these findings suggest that there is a “natural sensitivity” for PE1 to be recognized as a PE even if the splice defect is located far downstream. Intron 44 variant c.6148-84A>T interestingly resulted in three abnormal splice products involving different PE insertions with or without flanking exon 44 or 45 deletions. Follow-up studies employing patient-derived retinal-like cells are required to validate these complex splicing patterns.

In Table S20, we listed all published 353 DI variant alleles.5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,18,26,27 The three most frequent are c.4253+43G>A (n = 100), c.4539+2001G>A (n = 64), and c.5196+1137G>A (n = 47). For some DI variants, the splice defects in HEK293T cells or patient-derived PPCs are very small (c.769-784C>T, c.1937+435G>C, c.1937-621G>A)9,28 (this study) or smaller than expected (c.4539+2001G>A, c.4539+2028C>T). We hypothesize that retina-specific splice factors play roles that are largely missing (HEK293T cells) or underrepresented (PPCs) compared with the normal retina.

Current state of knowledge on structural variants in ABCA4

In this study, 11 unique SVs with sizes ranging from 411 bp to 55.7 kb were readily identified employing an easy-to-use visual detection tool taking advantage of the high number of reads obtained from smMIPs-based sequencing. Although this tool needs further automation to increase its performance for the detection of smaller deletions or duplications, it demonstrated its efficiency for deletions as small as 411 bp. To our knowledge, 47 different SVs have been identified in STGD1 patients (Table S21), 25 of which have been published elsewhere. Forty SVs are deletions, ranging in size from 23 bp to complete deletion of the ABCA4 gene. There are six duplications, ranging from 24 bp to 26 kb, two indels, and one small insertion of 24 bp. As shown in Fig. S10, these SVs are spread over the entire gene. All SVs are rare, except for a 23-bp deletion affecting the splicing of exons 28 and 29 in 15 Israeli probands, as well as deletions spanning exons 20–22 and exon 6, both found in 6 probands, in Belgium/Germany/Netherlands and from Iberic origin, respectively, suggesting founder effects.

This genomic instability could be explained by the local genomic architecture (the presence of microhomology, repetitive elements, sequences forming non-B DNA conformations, and sequence motifs), leading to genomic rearrangements by impairing the replication process. For example, a microhomology of 1–4 bp may facilitate nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ)29 and longer microhomologies of between 5 and 25 bp may favor microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ).30 The assessment of the local architecture of deletions identified in this study lead us to rule out the non-allelic homologous recombination (NAHR) hypothesis (as no Alu sequence or L1 at any breakpoint was observed) and to propose the NHEJ or replication slippage models as the main implicated mechanisms (Table S18, Fig. S8). Indeed, the presence of microhomologies <5 bp in most of the junctions, and of scars characterized by insertion of several random nucleotides, could be a signature for NHEJ. Alternatively, several examples of an impaired replication fork have been noted that supports the replicative-based repair model. Indeed, despite the absence of repetitive elements of the same class at both sides of the breakpoints, their presence may initiate the formation of secondary structures, as repetitive elements could be more difficult to replicate, leading to an increased chance of replication fork stalling or collapsing.31 Finally, Oligo(G)n tracts displayed a significant overrepresentation in the breakpoint regions. Such structures can induce tetraplex formation32 and could also trigger rearrangement.

Uniparental isodisomy chromosome 1

UPD was found in one STGD1 case in this study, which represents the third STGD1 case showing UPD thus far reported.33,34 UPD is a rare event, with an estimated occurrence of 1 in 5000 or even fewer individuals.35 UPD was also described in six other inherited retinal dystrophy patients in which chromosomes 1, 2, and 6 were implicated.36,37,38,39,40,41 We cannot exclude that there are additional UPD cases in our cohort as segregation analysis was not performed for all homozygous cases. Our finding stresses the importance of segregation analysis in the parents’ DNAs as the recurrence risk for future offspring is very low in UPD families.

Missing heritability

In 174/1054 (16.5%) of probands, we identified only one (likely) causal allele. In view of the high carrier frequency of ABCA4 variants in the general population, estimated to be ~5%,3,14 about one-third of these monoallelic cases may be explained in this way. This may even be higher as we intentionally recruited monoallelic STGD and STGD-like probands for this study. Some causal variants may have escaped our attention. First, we have not focused on variants affecting transcription regulation. Thus far, there is limited evidence for ABCA4 variants affecting transcription,7 but the reported putative regulatory variants were not found in this study. As in silico tools (Alamut algorithms, SpliceAI)42 may not predict retina-specific splice defects, we may have missed some causal variants. Also, smMIPs-based sequencing may miss heterozygous deletions smaller than ~400 bp and will not detect insertions or inversions larger than ~40 bp. In addition, more refined functional tests of coding and noncoding ABCA4 variants are needed to understand the full genetic landscape of STGD1.

The major advantages of smMIPs-based ABCA4 sequencing compared with genome sequencing are that it (1) is at least an order of magnitude cheaper than genome sequencing, (2) results in much smaller data storage, and (3) requires no separate informed consent regarding secondary findings. Disadvantages of smMIPs are that (1) it is restricted to one or a few genes if including introns, (2) it is more cost-effective when large series are analyzed, (3) the analysis is suitable for the detection of CNVs but not for inversions and insertions, and (4) the sequencing procedure and variant calling require a specialized setup.

In our study a significant fraction of probands carried one (likely) causal variant or c.5603A>T as a single allele (239; 22.7%) or no causal variant (364; 34.5%). A more comprehensive smMIPs-based screening platform for these STGD-like cases would likely require the sequence analysis of an additional ~80 genes associated with inherited central vision defects.

As shown in this study, smMIPs-based analysis of the complete sequence(s) of one or a few genes implicated in clinically well-defined human diseases may allow the (re)analysis of hundreds to thousands of samples, in particular by targeting cohorts in developing countries in which low-cost analysis is crucial. A similar approach can be applied to all other frequent monogenic disorders to find missing variants in noncoding regions to provide a genetic diagnosis.

In conclusion, comprehensive sequence analysis of ABCA4 in 1054 unsolved STGD and STGD-like probands, splice assays in HEK293T cells, and SV analysis resulted in the identification of “dark matter” variants in 25% of biallelic STGD1 probands. Novel complex types of splice defects were identified for intron 13 and 44 variants. Together with published causal DI variants and SVs, a detailed genomic and transcriptomic landscape of ABCA4-associated STGD1 was thereby established.

References

Carss KJ, Arno G, Erwood M, et al. Comprehensive rare variant analysis via whole-genome sequencing to determine the molecular pathology of inherited retinal disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2017;100:75–90.

Blacharski PA, Newsome DA. Bilateral macular holes after Nd:YAG laser posterior capsulotomy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1988;105:417–418.

Cornelis SS, Bax NM, Zernant J, et al. In silico functional meta-analysis of 5,962 ABCA4 variants in 3,928 retinal dystrophy cases. Hum Mutat. 2017;38:400–408.

Sangermano R, Khan M, Cornelis SS, et al. ABCA4 midigenes reveal the full splice spectrum of all reported noncanonical splice site variants in Stargardt disease. Genome Res. 2018;28:100–110.

Khan M, Cornelis SS, Khan MI, et al. Cost-effective molecular inversion probe-based ABCA4 sequencing reveals deep-intronic variants in Stargardt disease. Hum Mutat. 2019;40:1749–1759.

Schulz HL, Grassmann F, Kellner U, et al. Mutation spectrum of the ABCA4 gene in 335 Stargardt disease patients from a multicenter German cohort—impact of selected deep intronic variants and common SNPs. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017;58:394–403.

Bauwens M, Garanto A, Sangermano R, et al. ABCA4-associated disease as a model for missing heritability in autosomal recessive disorders: novel noncoding splice, cis-regulatory, structural, and recurrent hypomorphic variants. Genet Med. 2019;21:1761–1771.

Braun TA, Mullins RF, Wagner AH, et al. Non-exomic and synonymous variants in ABCA4 are an important cause of Stargardt disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:5136–5145.

Sangermano R, Garanto A, Khan M, et al. Deep-intronic ABCA4 variants explain missing heritability in Stargardt disease and allow correction of splice defects by antisense oligonucleotides. Genet Med. 2019;21:1751–1760.

Zernant J, Xie YA, Ayuso C, et al. Analysis of the ABCA4 genomic locus in Stargardt disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:6797–6806.

Bauwens M, De Zaeytijd J, Weisschuh N, et al. An augmented ABCA4 screen targeting noncoding regions reveals a deep intronic founder variant in Belgian Stargardt patients. Hum Mutat. 2015;36:39–42.

Bax NM, Sangermano R, Roosing S, et al. Heterozygous deep-intronic variants and deletions in ABCA4 in persons with retinal dystrophies and one exonic ABCA4 variant. Hum Mutat. 2015;36:43–47.

Fadaie Z, Khan M, Del Pozo-Valero M, et al. Identification of splice defects due to noncanonical splice site or deep-intronic variants in ABCA4. Hum Mutat. 2019;40:2365–2376.

Maugeri A, van Driel MA, van de Pol DJR, et al. The 2588G -> C mutation in the ABCR gene is a mild frequent founder mutation in the western European population and allows the classification of ABCR mutations in patients with Stargardt disease. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64:1024–1035.

Rivera A, White K, Stohr H, et al. A comprehensive survey of sequence variation in the ABCA4 (ABCR) gene in Stargardt disease and age-related macular degeneration. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;67:800–813.

Jaakson K, Zernant J, Kulm M, et al. Genotyping microarray (gene chip) for the ABCR (ABCA4) gene. Hum Mutat. 2003;22:395–403.

Maia-Lopes S, Aguirre-Lamban J, Castelo-Branco M, Riveiro-Alvarez R, Ayuso C, Silva ED. ABCA4 mutations in Portuguese Stargardt patients: identification of new mutations and their phenotypic analysis. Mol Vis. 2009;15:584–591.

Albert S, Garanto A, Sangermano R, et al. Identification and rescue of splice defects caused by two neighboring deep-intronic ABCA4 mutations underlying Stargardt disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2018;102:517–527.

Charbel Issa P, Barnard AR, Herrmann P, Washington I, MacLaren RE. Rescue of the Stargardt phenotype in Abca4 knockout mice through inhibition of vitamin A dimerization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:8415–8420.

Allocca M, Doria M, Petrillo M, et al. Serotype-dependent packaging of large genes in adeno-associated viral vectors results in effective gene delivery in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1955–1964.

Lu B, Malcuit C, Wang S, et al. Long-term safety and function of RPE from human embryonic stem cells in preclinical models of macular degeneration. Stem Cells. 2009;27:2126–2135.

Cremers FPM, Cornelis SS, Runhart EH, Astuti GDN. Author response: penetrance of the ABCA4 p.Asn1868Ile allele in Stargardt disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59:5566–5568.

Runhart EH, Sangermano R, Cornelis SS, et al. The common ABCA4 variant p.Asn1868Ile shows nonpenetrance and variable expression of Stargardt disease when present in trans with severe variants. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59:3220–3231.

Zernant J, Lee W, Collison FT, et al. Frequent hypomorphic alleles account for a significant fraction of ABCA4 disease and distinguish it from age-related macular degeneration. J Med Genet. 2017;54:404–412.

Hafez M, Hausner G. Convergent evolution of twintron-like configurations: one is never enough. RNA Biol. 2015;12:1275–1288.

Zernant J, Lee W, Nagasaki T, et al. Extremely hypomorphic and severe deep intronic variants in the ABCA4 locus result in varying Stargardt disease phenotypes. Cold Spring Harb Mol Case Stud. 2018;4:a002733.

Nassisi M, Mohand-Said S, Andrieu C, et al. Prevalence of ABCA4 deep-intronic variants and related phenotype in an unsolved “one-hit” cohort with Stargardt disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:5053.

Runhart EH, Valkenburg D, Cornelis SS, et al. Late-onset Stargardt disease due to mild, deep-intronic ABCA4 alleles. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019;60:4249–4256.

Lieber MR. The mechanism of double-strand DNA break repair by the nonhomologous DNA end-joining pathway. Annu Rev Biochem. 2010;79:181–211.

McVey M, Lee SE. MMEJ repair of double-strand breaks (director’s cut): deleted sequences and alternative endings. Trends Genet. 2008;24:529–538.

Vissers LE, Bhatt SS, Janssen IM, et al. Rare pathogenic microdeletions and tandem duplications are microhomology-mediated and stimulated by local genomic architecture. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:3579–3593.

Bacolla A, Wells RD. Non-B DNA conformations, genomic rearrangements, and human disease. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:47411–47414.

Fingert JH, Eliason DA, Phillips NC, Lotery AJ, Sheffield VC, Stone EM. Case of Stargardt disease caused by uniparental isodisomy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:744–745.

Riveiro-Alvarez R, Valverde D, Lorda-Sanchez I, et al. Partial paternal uniparental disomy (UPD) of chromosome 1 in a patient with Stargardt disease. Mol Vis. 2007;13:96–101.

Liehr T. Cytogenetic contribution to uniparental disomy (UPD). Mol Cytogenet. 2010;3:8.

Rivolta C, Berson EL, Dryja TP. Paternal uniparental heterodisomy with partial isodisomy of chromosome 1 in a patient with retinitis pigmentosa without hearing loss and a missense mutation in the Usher syndrome type II gene USH2A. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:1566–1571.

Roosing S, van den Born LI, Hoyng CB, et al. Maternal uniparental isodisomy of chromosome 6 reveals a TULP1 mutation as a novel cause of cone dysfunction. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:1239–1246.

Thompson DA, Gyurus P, Fleischer LL, et al. Genetics and phenotypes of RPE65 mutations in inherited retinal degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:4293–4299.

Thompson DA, McHenry CL, Li Y, et al. Retinal dystrophy due to paternal isodisomy for chromosome 1 or chromosome 2, with homoallelism for mutations in RPE65 or MERTK, respectively. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:224–229.

Wiszniewski W, Lewis RA, Lupski JR. Achromatopsia: the CNGB3 p.T383fsX mutation results from a founder effect and is responsible for the visual phenotype in the original report of uniparental disomy 14. Hum Genet. 2007;121:433–439.

Souzeau E, Thompson JA, McLaren TL, et al. Maternal uniparental isodisomy of chromosome 6 unmasks a novel variant in TULP1 in a patient with early onset retinal dystrophy. Mol Vis. 2018;24:478–484.

Jaganathan K, Kyriazopoulou Panagiotopoulou S, McRae JF, et al. Predicting splicing from primary sequence with deep learning. Cell. 2019;176:535–48 e524.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ellen Blokland, Duaa Elmelik, Emeline Gorecki, Marlie Jacobs-Camps, Charlene Piriou, Mariateresa Pizzo, and Saskia van der Velde-Visser for technical assistance. We thank Béatrice Bocquet, Dominique Bonneau, Krystyna H. Chrzanowska, Hélene Dollfus, Isabelle Drumare, Monika Heusipp, Takeshi Iwata, Beata Kocyła-Karczmarewicz, Atsushi Mizota, Nobuhisa Nao-i, Adrien Pagin, Valérie Pelletier, Rafal Ploski, Agnieszka Rafalska, Rosa Riveiro, Malgorzata Rydzanicz, Blanca Garcia Sandoval, Kei Shinoda, Francesco Testa, Kazushige Tsunoda, Shinji Ueno, and Catherine Vincent-Delorme for their cooperation and ascertaining STGD1 cases. We thank Rolph Pfundt for his assistance in exome sequencing data analysis. We are grateful to the Eichler and Shendure labs (Department of Genome Sciences, University of Washington), for assistance with the initial MIP protocol. We thank the European Reference Network (ERN)-EYE and European Retinal Disease Consortium (ERDC) networks, the Japan Eye Genetics Consortium, and the East Asian Inherited Retinal Disease Society.

This work was supported by the RetinaUK, grant number GR591 (to F.P.M.C.); a Fighting Blindness Ireland grant, grant number FB18CRE (to F.P.M.C., G.J.F.); a Horizon 2020, Marie Sklodowska-Curie Innovative Training Network entitled European Training Network to Diagnose, Understand and Treat Stargardt Disease; Frequent Inherited Blinding Disorder-StarT (813490) (to E.D.B., F.P.M.C., S.B., G.J.F.); Foundation Fighting Blindness USA, grant number PPA-0517-0717-RAD (to F.P.M.C.); the Rotterdamse Stichting Blindenbelangen, the Stichting Blindenhulp, and the Stichting tot Verbetering van het Lot der Blinden (to F.P.M.C.); and by the Landelijke Stichting voor Blinden en Slechtzienden, Macula Degeneratie fonds and the Stichting Blinden-Penning that contributed through Uitzicht 2016-12 (to F.P.M.C.). This work was also supported by the Algemene Nederlandse Vereniging ter Voorkoming van Blindheid and Landelijke Stichting voor Blinden en Slechtzienden that contributed through UitZicht 2014-13, together with the Rotterdamse Stichting Blindenbelangen, Stichting Blindenhulp, and the Stichting tot Verbetering van het Lot der Blinden (to F.P.M.C.). This work was also supported by Groupement de Coopération Sanitaire Interrégional G4 qui réunit les Centres Hospitaliers Universitaires Amiens, Caen, Lille et Rouen (GCS G4) and by the Fondation Stargardt France (to C.-M.D.), Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), grant numbers 01GM0851 and 01GM1108B (to B.H.F.W.), programs SVV 260516, UNCE 204064, and PROGRES-Q26/LF1 of the Charles University (to B.K., L.D., P.L.). This work was supported by grant AZV NU20-07-00182 (to P.L., B.K. and L.D.). The work of A.D. was supported by Fighting Blindness Ireland, Health Research Board of Ireland and the Medical Research Charities Group (MRCG-2016-14) (to G.J.F.). This work was supported by grant AZV NU20-07-00182 (to P.L., B.K., L.D.). This work was also supported by the Ghent University Research Fund (BOF15/GOA/011), by the Research Foundation Flanders (FVO) G0C6715N, by the Hercules foundation AUGE/13/023 and JED Foundation (to E.D.B.). M.B. was PhD fellow of the FWO and recipient of a grant of the funds for Research in Ophthalmology (FRO). E.D.B. is Senior Clinical Investigator of the FWO (1802215N; 1802220N). The work of M.D.P-.V. is supported by the Conchita Rábago Foundation and the Boehringer Ingelheim Fonds. The work of C.A. is supported by grants PI16/0425 from ISCIII partially supported by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), RAREGenomics-CM (CAM, B2017/BMD-3721), ONCE, and Ramon Areces Foundation. This work was supported by the Peace for Sight grant (to D.S., A.A.). The work of L.R. and R.R. was supported by Retina South Africa and the South African Medical Research Council (MRC). This work was also supported by the Foundation Fighting Blindness, grant/award number BR‐GE‐0214–0639‐TECH and BRGE‐0518–0734‐TECH (to T.B.-Y., D.S., H.N.); the Israeli Ministry of Health, grant/award number 3‐12583Q4 (to T.B.-Y., D.S., H.N.); Olive Young Fund, University Hospital Foundation, Edmonton (to I.M.M.); the National Science Center (Poland) grant number N N402 591640 (5916/B/P01/2011/40) (to M.O.); and UMO-2015/19/D/NZ2/03193 (to A.M.T.). This work was supported by the Italian Fondazione Roma (to S.B., F.S.), the Italian Telethon Foundation (to S.B.), and the Ministero dell’Istruzione del l’Università e della Ricerca (MIUR) under PRIN 2015 (to S.B., F.S.). M.B.G. and A.M. were supported by the Daljit S. and Elaine Sarkaria Charitable Foundation. The funding organizations had no role in the design or conduct of this research, and provided unrestricted grants.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Khan, M., Cornelis, S.S., Pozo-Valero, M.D. et al. Resolving the dark matter of ABCA4 for 1054 Stargardt disease probands through integrated genomics and transcriptomics. Genet Med 22, 1235–1246 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-020-0787-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-020-0787-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Combining a prioritization strategy and functional studies nominates 5’UTR variants underlying inherited retinal disease

Genome Medicine (2024)

-

Benchmarking splice variant prediction algorithms using massively parallel splicing assays

Genome Biology (2023)

-

A multidisciplinary approach to inherited retinal dystrophies from diagnosis to initial care: a narrative review with inputs from clinical practice

Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases (2023)

-

Detailed analysis of an enriched deep intronic ABCA4 variant in Irish Stargardt disease patients

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Functional characterization of ABCA4 genetic variants related to Stargardt disease

Scientific Reports (2022)