Abstract

Purpose

Hearing loss (HL) is the most common sensory disorder in children. Prompt molecular diagnosis may guide screening and management, especially in syndromic cases when HL is the single presenting feature. Exome sequencing (ES) is an appealing diagnostic tool for HL as the genetic causes are highly heterogeneous.

Methods

ES was performed on a prospective cohort of 43 probands with HL. Sequence data were analyzed for primary and secondary findings. Capture and coverage analysis was performed for genes and variants associated with HL.

Results

The diagnostic rate using ES was 37.2%, compared with 15.8% for the clinical HL panel. Secondary findings were discovered in three patients. For 247 genes associated with HL, 94.7% of the exons were targeted for capture and 81.7% of these exons were covered at 20× or greater. Further analysis of 454 randomly selected HL-associated variants showed that 89% were targeted for capture and 75% were covered at a read depth of at least 20×.

Conclusion

ES has an improved yield compared with clinical testing and may capture diagnoses not initially considered due to subtle clinical phenotypes. Technical challenges were identified, including inadequate capture and coverage of HL genes. Additional considerations of ES include secondary findings, cost, and turnaround time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hearing loss (HL) affects nearly 1 in 500 infants.1,2 More than half of the cases of congenital or early-onset bilateral sensorineural HL (BLSNHL) have a genetic cause, the remainder being either acquired or idiopathic.2,3 Genetic etiologies can be further divided into isolated (nonsyndromic) HL or HL associated with dysmorphisms and/or additional medical problems (syndromic). Nonsyndromic HL comprises about 70% of genetic cases.4 With the recognition that early detection and diagnosis of HL improves health outcomes, hearing screenings have been implemented in the newborn period5. However, molecular diagnostic ascertainment of the underlying cause to help guide counseling and management remains challenging.

One of the challenges of molecular diagnostics for HL is the high Degree of genetic heterogeneity; approximately 1% (~250) of human genes are necessary for a functional auditory system.6 Over 70 genes are implicated in isolated BLSNHL, for which phenotypic clues are limited to the type and severity of HL without additional nonaudiological features to help guide a molecular workup.2 Syndromic cases can be just as challenging to diagnose, as neonates may not yet have developed additional clinical features to guide molecular diagnostics. Moreover, variants in genes known to cause syndromic HL have been identified in patients with nonsyndromic HL.7

Due to the high degree of genetic heterogeneity and phenotypic overlap, HL is well suited to the strengths of “next-generation sequencing” (NGS). NGS is the basis for a collection of clinical tests that allow rapid sequencing of genomic material using a common method.8 Multiple genes associated with a specific diagnosis may be targeted in “gene panels”, and with “exome sequencing” (ES) all protein-coding exons can be targeted.

The increased scope of ES leads to additional challenges, including increased cost, lengthy turnaround time, analytic burden of variants of uncertain significance (VUSs) and identification of secondary findings unrelated to HL. ES covers a much larger portion of the genome than targeted panels. It allows for reanalysis of data for genes newly associated with HL that were not known initially. However, the coverage over any given set of genes may be inconsistent.

ES was initially used in the research setting to identify new HL genes (reviewed in9), and now gene panels are the molecular diagnostic gold standard for HL if the etiology remains unknown after evaluation (history, physical examination, and testing for cytomegalovirus if appropriate).10 Diagnostic rates for these panels range from 16 to 42%, with greater success in nonsyndromic cases.11,12,13,14 Targeted analysis of the exome to analyze 120 genes—a similar size to current HL panels—identified causative variants in 33.5% of patients.15 The strength of NGS genetic testing and potentially ES in contributing to the management and diagnostic yield for HL has led to recent recommendations for a “genetics-first” approach to the etiologic workup.16

We examined the efficacy of ES as a diagnostic tool in HL by evaluating the diagnostic yield in an expanded list of 247 genes associated with HL, and the capture and coverage across a broad spectrum of HL loci. We present clinical vignettes to highlight the strengths and limitations of this approach.

Materials and methods

The Institutional Review Board at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) approved the Pediatric Sequencing (PediSeq) Project at the CHOP—part of the National Human Genome Research Institute Clinical Sequencing Exploratory Research Consortium. In total, 191 patients were enrolled and provided informed consent for research ES. Of these individuals, 43 had HL (the majority had BLSNHL). Individual patient information was de-identified.

Patients with HL were recruited to the PediSeq project from the Genetics of Hearing Loss Clinic at the CHOP (Table 1). Clinical information was based on the clinical documentation. The primary focus of the study was on BLSNHL, but a small number of probands with other forms of HL were also enrolled if a genetic etiology was suspected. Clinical testing (if approved by insurance) was performed in parallel to research exome. About one-quarter of the patients (27.9%) were diagnosed with congenital HL and another quarter (23.3%) were diagnosed with prelingual HL (defined as being identified at less than or equal to 1 year of age). The remainder had postlingual HL (defined as being identified after 1 year of age). Although there were a few cases of syndromic HL (9.3%), the majority of cases (90.7%) were nonsyndromic. Sensorineural HL (SNHL) was the major type (83.7%). There was one case of conductive HL (2.3%) and six cases of mixed (sensorineural and conductive) HL (14%). Two patients had unilateral HL (4.7%), while the majority had bilateral HL (95.3%). Almost half the patients had a family history of HL (46.5%) and approximately half did not (48.8%), although two patients (4.7%) were unsure whether there was a family history of HL. The demographics of the patient population are provided in Table 1.

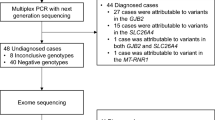

In parallel with research ES, 32 of 43 patients (74.4%) had gene panel and/or copy-number variant (CNV) analysis performed (Table 1). Four of 43 patients (9.3%) had the HL panel available at the CHOP (Sanger sequencing of GJB2 (exons 1 and 2), GJB6 (deletion region), MTRNR1 (entire gene), and SLC26A4 (exons 6, 9, 10, and 19)). Nineteen of 43 patients (44.2%) had GJB2 sequencing with reflex testing on OtoGenome version 1 or 2 (71 or 70 genes, respectively; Partners HealthCare, Boston, MA). Five of 43 patients (11.6%) had targeted or single-gene testing performed, including single-gene tests for EYA1, SIX1, SHOX, and PAX3, as well as Waardenburg syndrome and Usher Syndrome panel testing. One patient (2.3%) had clinical ES. Twenty-four of 43 patients (55.8%) had a chromosomal microarray. Multiple patients had more than one test sent. Other clinical tests included fragile X testing and distal motor neuropathy gene panel testing. Fragile X testing was excluded from the analysis as this has not been associated with HL.17

Peripheral blood was collected from patients and stored immediately at 4 °C. Genomic DNA was extracted manually by standard procedures using the Gentra Puregene Blood Kit Plus (158489; Qiagen, Germantown, MD) and 3–6 μg was used for further analysis. Exome capture was performed using the SureSelect version 4 capture kit (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) and 100-base pair paired-end sequencing was performed on HiSeq 2500 sequencers (Illumina, San Diego, CA) at the Bejing Genomics Institute at the CHOP sequencing facility. The average depth of coverage was 100×. Sequencing reads were generated in FASTQ format and analyzed using the PediSeq ES pipeline. Sequences were mapped to human genome assembly GRCh37.p10. Novoalign (version 3.00.02; www.novocraft.com) was used for optimal alignment. The GATK Variant Filtration tool was used to filter reads with low quality and strand bias. The GATK Depth of Coverage tool (version 2.2) was used to obtain capture and coverage statistics of exons and genomic positions. Quality control steps during variant calling included minBaseQuality 20/minMappingQuality 20 settings and exclusion of variants with a depth of coverage of fewer than 10 reads. CNVs were identified using the R package ExomeDepth.18 Each sample was compared with the entire PediSeq cohort. An average of 79 CNVs per individual were identified. Rare variants were filtered by comparing their frequency against the frequency within our internal cohort and the Database of Genomic Variants. Ten validation samples with previously identified causative HL pathogenic variants (PV), including three CNVs, were run through the pipeline blinded. Each of these diagnoses was captured and identified on ES (Supplementary Table 1).

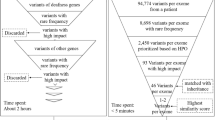

A list of 247 genes related to HL was manually curated using information from the Gene List Automatically Derived For You gene list generator using the terms “hearing loss” and “deafness”19 and previously established HL gene panels (listed at genetests.org20) (Supplementary Table 2). From reports in the literature, 72 genes had nonsyndromic presentations, 154 had syndromic phenotypes and 21 had syndromic and nonsyndromic phenotypes. This gene list was used as a primary filter to examine capture by the Agilent SureSelect version 4 kit and coverage of HL-associated genes. Exon coverage was defined by the percentage of the bases in the exon covered at 20× sequencing depth. Previous work suggested that 8× and 13× are the minimums for calling homozygous and heterozygous variants, respectively.21 At a level of 20× coverage, there is enough power to detect heterozygous variants with at least a 20% variant allele frequency.22

Some 14,598 variants were associated with the 247 HL genes in the Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD)—a collection of genetic variants associated with human disease.23 For each gene, up to two variants within exon boundaries were randomly selected for coverage analysis using our ES platform. These variants were then manually curated to ensure each variant had been reported with a HL phenotype (as not all annotated variants in the HGMD may be truly associated with disease24), yielding 454 variants selected for capture and coverage analysis (Supplementary Table 3).

For primary analysis, variants were generated from the 247 genes in our HL gene list using the Exome Aggregation Consortium database (minor allele frequency (MAF) <0.05) and our internal cohort (MAF <5%) as filters. Variants were not limited to HGMD variants. Variants were analyzed according to American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics standards.25 Exome analysts were blinded to the clinical test results. The rare variants were manually assigned a pathogenicity call (benign, likely benign, VUS, likely pathogenic, or pathogenic). Similarly, for secondary findings, the variants were generated using the same filters (Exome Aggregation Consortium: MAF <0.05%; internal cohort: MAF <5%) from a set of 2,956 medically actionable genes developed from the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man compendium, genetests.org and the HGMD. All rare missense variants were then filtered against the HGMD database, and only those reported in the HGMD were analyzed to determine pathogenicity. Frameshift, insertions/deletions, splice-site and nonsense variants were analyzed irrespective of whether or not they were reported in the HGMD. We categorized the results into immediately medically actionable, childhood- or adult-onset medically actionable, and carrier status. For the carrier status, we interpreted similar rare variants within 185 autosomal recessive disorder genes. Secondary findings were analyzed for all patients, although 7 of 43 probands (16.3%) opted out of specific secondary findings (Table 2). A clinical laboratory director certified by the American Board of Medical Genetics and Genomics confirmed all variant calls. Parental studies were performed as required to verify inheritance. Clinical Sanger sequencing confirmed the variants identified by ES before the results were returned to the patient.

After the initial analysis, we reviewed the literature and attempted to expand the gene list. No new pathogenic findings were reportable after re-running the samples. There were VUS in genes of limited clinical validity, which did not meet our reportable criteria. At the time of revision, updated clinical ES identified a likely pathogenic variant in AMMECR1, which was not included in this analysis.

Results

A genetic diagnosis for HL was identified in 17 of 43 probands (39.5%), with research ES identifying a diagnosis in 16 of 43 probands (37.2%) (Tables 2 and 3). CNVs were identified in three patients, although none definitively contributed to the patient's HL. One patient had a deletion on chr1q24.2 containing SLC19A2, which causes autosomal recessive thiamine-responsive megaloblastic anemia syndrome, progressive SNHL, and diabetes mellitus, but sequencing of the other allele was normal. Another patient had a deletion on chr15q13.1, although this was also present in the patient’s son who did not have HL. The third patient had a small duplication on 22q11.2, which was called as a VUS. Three of 19 patients (15.8%) received a diagnosis by GJB2 sequencing with reflex testing on the OtoGenome panel. Neither the four patients with the CHOP HL panel nor the five patients with targeted testing received a genetic diagnosis through clinical testing. For the 17 diagnosed cases, the inheritance pattern was recessive for 11 cases (64.7%), dominant for 5 cases (29.4%), and X-linked for 1 case (5.9%) (Table 2). Of the 11 recessive cases, 5 (29.4%) were homozygous and 6 (35.3%) were compound heterozygotes. Of the 5 dominant cases, 3 (17.6%) were inherited dominant PV and 2 (11.8%) were de novo dominant PV. ES did not identify a primary diagnosis for 26 out of 43 probands (60.5%).

The majority of families in this cohort chose to be notified of secondary findings (Tables 2 and 3). Two probands (4.7%) had immediately medically actionable secondary findings in 3 genes associated with familial hypercholesterolemia, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and retinitis pigmentosa. One proband (2.3%) had an adult-onset medically actionable secondary finding in a gene associated with hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. Carrier status was identified in 27 patients (63%) during analysis for secondary findings.

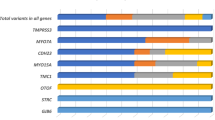

To further examine the diagnostic capabilities of ES for HL, capture and coverage analysis was performed for the 247 pathogenic HL genes (4,421 exons; Fig. 1a, b) and 454 variants (Fig. 1c, d), as described in the “Materials, patients and methods” section. The capture kit used for ES targeted 94.7% of the exons of the 247 HL genes and 89% of these variants for capture. Coverage of an exon was defined as at least 20×. In total, 81.7% of the captured exons had coverage over the entire exon. For 3.8% of captured exons, 90 to <100% coverage of the exon was seen. For 4.1% of captured exons, 70 to <90% coverage of the exon was seen. For 4.3% of captured exons, 40 to <70% coverage of the exon was seen. For 6.1% of captured exons, <40% coverage of the exon was seen. In total, 75.0% of variants were fully covered (defined as at least 20×), 17.6% had 10 to <20× coverage, 6.4% had 1 to <10× coverage, and the remainder had <1× coverage. The exons and variants that did not have at least 20× coverage in 50% of samples are identified in Supplementary Tables 3 and 4.

a Distribution of exons for HL genes that are targeted for capture by the Agilent SureSelect version 4 capture kit. b Coverage data by exon. c Distribution of selected variants from HL genes that are targeted for capture by the Agilent SureSelect version 4 capture kit. d Coverage data by variant. e Distribution of exons of GJB2, OTOA, and STRC that are targeted for capture by the Agilent SureSelect version 4 capture kit. f Coverage data by exon

We assessed the capture and coverage by ES for three specific genes associated with HL: GJB2, OTOA, and STRC (Fig. 1e, f). GJB2 is the most common molecular cause of HL. OTOA and STRC were selected as they both have highly homologous pseudogenes that complicate molecular diagnostics. One out of two GJB2 exons was targeted for capture, and the targeted exon had poor coverage. For 3 differentially spliced OTOA transcripts, 70% of the 30 exons were targeted for capture. Experimentally, 70% of the OTOA exons had at least 90% of the sequence covered at 20×, while about 30% of the OTOA exons had less than 40% coverage at 20×. For STRC, 7 of 29 exons (24.1%) were targeted for capture. Of these exons, 13% were well covered (>90 to <100% at 20×), 3% were mostly covered (>70 to 90% at 20×), and the majority (83%) were not covered (<40% coverage at 20×).

Illustrative case examples

BRCA1 variant as an example of a medically actionable secondary finding

A 4-month-old girl with history of nasolacrimal duct obstruction presented after failing her newborn hearing screen. Family history, including her three older siblings, was negative for HL but significant for a paternal aunt with ovarian cancer. Both research ES and clinical GJB2 sequencing identified homozygous PV in GJB2 (c.35delG; p.G12fs). ES also discovered a pathogenic variant (c.5503C>T; p.R1835*) in BRCA1—a well-known tumor suppressor associated with autosomal dominant hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. This case demonstrates the importance of secondary findings from ES. This patient has a significantly increased cancer risk, and it is likely that other family members do as well. These results were returned with genetic counseling and the family was scheduled for follow-up in a cancer genetics clinic.

ES identifies molecular etiology before clinical features are available to guide diagnostic testing

A six-day-old boy was evaluated for dysmorphic features and mild to moderate BLSNHL, which was diagnosed after a failed newborn hearing screen. Physical examination revealed three fontanels, a sacral dimple, telecanthus, posteriorly rotated ears, and head lag. The family history was negative for both HL and dysmorphic features, including a healthy older brother. Given the combination of telecanthus and HL, targeted PAX3 gene testing to evaluate for Waardenburg syndrome type I and chromosomal microarray was requested. Both tests returned normal results. Research ES identified two PV in the PEX1 gene, consistent with Zellweger syndrome—a peroxisomal biogenesis disorder. Over the next few months, additional features of peroxisomal biogenesis disorders became evident, such as hypotonia, severe developmental delay, abnormal eye movements, and tapetoretinal degeneration identified by magnetic resonance imaging.

A five-week-old newborn female presented for small size and conductive HL. Physical examination was notable for growth in the fifth to tenth percentile, a thin upper lip, and prominent maxilla. At 28 months, she had delayed expressive and receptive language and mild behavioral problems. Family history, including her two siblings, was negative for any hearing impairment or developmental delays. The results of a chromosomal microarray were normal. ES performed through the PediSeq research study identified a de novo frameshift variant in the EFTUD2 gene (c.764dup; p.Cys256Valfs*6) associated with autosomal dominant mandibulofacial dysostosis with microcephaly, which is associated with conductive HL and characteristic facial features.

Although variants in PEX1 and EFTUD2 result in syndromic HL, these genes are not present on any HL gene panels in the United States.20 In both cases, ES was essential for early diagnosis before the additional syndromic features were present.

ES identifies a diagnosis not present on standard clinical testing

A 2-year-old male presented with language delay and progressive moderate to profound BLSNHL, necessitating hearing aids. The proband had three brothers with normal hearing. His mother had congenital progressive unilateral SNHL, also necessitating a hearing aid. The maternal grandfather had BLSNHL. The patient was consented for research ES in the PediSeq study while connexin 26 (GJB2) sequencing with reflex testing on the OtoGenome panel, Waardenburg syndrome testing, and chromosomal microarray analysis were requested.

OtoGenome and research ES revealed three VUSs (one missense heterozygous variant each in DFNB31, MYO15A, and USH2A). Chromosomal microarray and Waardenburg syndrome testing returned normal results. ES also identified a maternally inherited pathogenic variant in the SMPX gene (c.133-1G>A). PV in SMPX cause X-linked dominant nonsyndromic HL, characterized by SNHL starting in the first decade of life for males.26,27,28 This explains the family history of unilateral HL in the mother and BLSNHL in the grandfather, as the onset and severity of the condition are more variable for females. In this case, ES identified the genetic etiology, as the OtoGenome panel did not include SMPX.

Clinical testing, but not ES, provides the diagnosis

An 11-year-old female presented with mild to moderately severe BLSNHL. The proband had no family history of HL. The patient was consented for research ES while connexin 26 (GJB2) sequencing with reflex testing on the OtoGenome panel were requested. Research ES identified a single pathogenic variant in the GJB2 gene (c.71G>A; p.W24*). Clinical testing identified the same GJB2 pathogenic variant as ES and an additional pathogenic variant present in intron 1 (noncoding) of the GJB2 gene (c.-23+1G>A). This intronic variant was not identified using ES because the intron was not targeted by the capture kit. This case demonstrates a potential limitation of ES as a diagnostic tool, and the importance of carefully examining the coverage of any genes associated with the phenotype being evaluated.

Discussion

Research ES on a cohort of 43 patients with HL identified a molecular etiology in 37.2% of probands, similar to the 39% diagnostic rate reported for the OtoSCOPE HL gene panel.13 In comparison, 15.8% of the probands that had GJB2 sequencing with reflex testing on the OtoGenome panel received a diagnosis.

Clinical testing was limited due to insurance, so we examined the variants for cases diagnosed by research ES. We estimate that 9 of 16 patients would receive a molecular etiology by OtoGenome testing, assuming that any variant in a covered region would be detected. Seven patients had variants in COCH, GJB2, MYO15A, or EYA1 that would probably have been detected by OtoGenome testing. For five other cases, the causative gene was not included in the OtoGenome testing (EFTUD2, PEX1, SMPX, SIX1, and OTOG), although SIX1 is included in the current OtoGenome test. For two cases, OtoGenome testing did not confirm both variants detected on ES.

This study demonstrates that poor capture and coverage is a limitation of the use of ES in the genetic diagnosis of HL. Incomplete capture may lead to a failed diagnosis, such as the proband with an intronic GJB2 PV that was identified by clinical testing but not ES. ES may be limited due to poor sequencing coverage issues (e.g., homopolymeric regions or GC-rich regions) or mapping issues (e.g., pseudogenes or large deletions), as demonstrated by the coverage of STRC and OTOA. Improvements in capture technology and enrichment for known disease genes to optimize the capture and coverage of HL genes will improve the performance of ES in the future. Targeted Sanger sequencing can supplement consistently poorly covered regions in exome-based testing. This finding suggests that tiered clinical testing may be beneficial. Examples of tiered clinical testing for HL include GJB2 gene testing with reflex testing of smaller panels (some of which are now exome-based “slices”, in which ES is performed and a list of HL genes are analyzed first, and then reflex testing of the full ES is offered if desired) before ES.

CNVs are implicated in 18.7% of HL cases with a genetic etiology, about 86% of which are CNVs in STRC and OTOA.29 Our validation cases showed that CNVs are detected by ES, but in our cohort, we did not find any pathogenic deletions or duplications in GJB2, OTOA or STRC. Genes and pseudogenes with high homology can create ambiguity in mapping of the short reads. Thus, CNV calling using short-read ES in genes with pseudogenes, such as OTOA and STRC, is challenging. This is one of the shortcomings of the short-read sequencing technology. Supplementation of ES with array comparative genomic hybridization may be helpful in CNV detection.

The use of ES for molecularly diagnosing HL provides some benefits over standard genetic diagnostic protocols. In cases of nonsyndromic HL, early diagnosis may help direct care for associated medical comorbidities (e.g., in patients with Usher, Pendred, Jervell, or Lange–Nielsen syndromes). Additionally, ES may identify novel candidate genes, diagnoses that would not be identified with targeted testing, or diagnoses associated with syndromic HL when the additional clinical features are not present to help guide testing, as seen in the above cases. If a primary diagnosis is not found initially, the diagnostic yield may be improved by reanalysis when additional genotype or phenotype information is available, such as the revised clinical ES report with a likely PV in AMMECR1, which we are examining for clinical relevance.

Another consideration is that ES has a high likelihood of identifying VUS, especially in under-represented minority populations for whom there are less robust control genomic data. This can complicate the counseling of affected families. As more patients undergo ES, there will be more opportunities to share data that will improve the identification of nonpathogenic variants compared with pathogenic variants, as well as the racial distribution of these variants, thereby decreasing the uncertainty associated with broad-scale genomic tests. Although our study did not examine cost and turnaround time (for both, the sequencing as well as the variant analysis), these will continue to decrease, making ES more competitive.

The rate of secondary findings of almost 7% in our cohort is not much higher than the rate of 4.6% previously published by Yang et al.30 The BRCA1 case discussed above highlights the importance of informed consent for ES and the benefit that identifying secondary findings may have for the entire family. Additionally, in almost two-thirds of the patients, carrier status was identified that may alter future reproductive decisions. While the identification of medically actionable secondary findings may have the benefit of early diagnosis, counseling and management, this should be undertaken only if desired and consented by the families, as some may find this information overwhelming and undesirable.

In summary, ES is a potentially powerful tool for the molecular diagnosis of HL. It has enabled the molecular identification of HL genes not present on gene panels and the identification of unsuspected molecular etiologies, and performed well for identifying common genetic causes of HL. Limitations and concerns remain around the ability of ES to provide adequate coverage for all genes, exons, and variants known to cause HL at the same rate as targeted gene tests or HL gene panels. Tiered genetic testing or exome “slices” may be a solution to address these issues. Additional considerations include the identification of VUSs and secondary unrelated findings, as these may complicate counseling for affected families, but may also lead to the identification of medically actionable variants.

References

Morton NE. Genetic epidemiology of hearing impairment. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1991;630:16–31.

Morton CC, Nance WE. Newborn hearing screening—a silent revolution. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2151–64.

Marazita ML, Ploughman LM, Rawlings B, Remington E, Arnos KS, Nance WE. Genetic epidemiological studies of early-onset deafness in the U.S. school-age population. Am J Med Genet. 1993;46:486–91.

Smith RJH, Bale JF, White KR. Sensorineural hearing loss in children. Lancet. 2005;365:879–90.

Nelson HD, Bougatsos C, Nygren P. 2001 US Preventive Services Task Force. Universal newborn hearing screening: systematic review to update the 2001 US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e266–76.

Smith SD, Toriello HV, editors. Hereditary hearing loss and its syndromes, 3rd ed. Oxford University Press, New York, NY; 2013.

Bademci G, Cengiz FB, Foster Ii J, et al. Variations in multiple syndromic deafness genes mimic non-syndromic hearing loss. Sci Rep. 2016;6:31622.

Bosch ten JR, Grody WW. Keeping up with the next generation: massively parallel sequencing in clinical diagnostics. J Mol Diagn. 2008;10:484–92.

Vona B, Nanda I, Hofrichter MAH, Shehata-Dieler W, Haaf T. Non-syndromic hearing loss gene identification: a brief history and glimpse into the future. Mol Cell Probes. 2015;29:260–70.

Prosser JD, Cohen AP, Greinwald JH. Diagnostic evaluation of children with sensorineural hearing loss. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2015;48:975–82.

Shearer AE, Black-Ziegelbein EA, Hildebrand MS, et al. Advancing genetic testing for deafness with genomic technology. J Med Genet. 2013;50:627–34.

Mandelker D, Amr SS, Pugh T, et al. Comprehensive diagnostic testing for stereocilin: an approach for analyzing medically important genes with high homology. J Mol Diagn. 2014;16:639–47.

Sloan-Heggen CM, Bierer AO, Shearer AE, et al. Comprehensive genetic testing in the clinical evaluation of 1119 patients with hearing loss. Hum Genet. 2016;135:441–50.

Shearer AE, Smith RJH. Massively parallel sequencing for genetic diagnosis of hearing loss: the new standard of care. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;153:175–82.

Zazo Seco C, Wesdorp M, Feenstra I, et al. The diagnostic yield of whole-exome sequencing targeting a gene panel for hearing impairment in The Netherlands. Eur J Hum Genet. 2017;25:308–14.

Liming BJ, Carter J, Cheng A, et al. International Pediatric Otolaryngology Group (IPOG) consensus recommendations: hearing loss in the pediatric patient. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;90:251–8.

Roberts J, Hennon EA, Anderson K, et al. Auditory brainstem responses in young males with fragile X syndrome. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2005;48:494–500.

Plagnol V, Curtis J, Epstein M, et al. A robust model for read count data in exome sequencing experiments and implications for copy number variant calling. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:2747–54.

Jourquin J, Duncan D, Shi Z, Zhang B. GLAD4U: deriving and prioritizing gene lists from PubMed literature. BMC Genom. 2012;13:S20.

Gene Tests. BioReference Laboratories in Elmwood Park, NJ. https://www.genomeweb.com/molecular-diagnostics/longstanding-genetic-testing-website-genetestsclosing#.WxJpyq3MxE4. Accessed 10 May 2017.

Meynert AM, Bicknell LS, Hurles ME, Jackson AP, Taylor MS. Quantifying single nucleotide variant detection sensitivity in exome sequencing. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013;14:195.

Rennert H, Eng K, Zhang T, et al. Development and validation of a whole-exome sequencing test for simultaneous detection of point mutations, indels and copy-number alterations for precision cancer care. NPJ Genom Med. 2016;1:16019.

Stenson PD, Mort M, Ball EV, Shaw K, Phillips A, Cooper DN. The Human Gene Mutation Database: building a comprehensive mutation repository for clinical and molecular genetics, diagnostic testing and personalized genomic medicine. Hum Genet. 2014;133:1–9.

Xue Y, Chen Y, Ayub Q, et al. Deleterious- and disease-allele prevalence in healthy individuals: insights from current predictions, mutation databases, and population-scale resequencing. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;91:1022–32.

Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405–24.

Weegerink NJD, Huygen PLM, Schraders M, Kremer H, Pennings RJE, Kunst HPM. Variable degrees of hearing impairment in a Dutch DFNX4 (DFN6) family. Hear Res. 2011;282:167–77.

Huebner AK, Gandia M, Frommolt P, et al. Nonsense mutations in SMPX, encoding a protein responsive to physical force, result in X-chromosomal hearing loss. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88:621–7.

Schraders M, Haas SA, Weegerink NJD, et al. Next-generation sequencing identifies mutations of SMPX, which encodes the small muscle protein, X-linked, as a cause of progressive hearing impairment. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88:628–34.

Shearer AE, Kolbe DL, Azaiez H, et al. Copy number variants are a common cause of non-syndromic hearing loss. Genome Med. 2014;6:37.

Yang Y, Muzny DM, Xia F, et al. Molecular findings among patients referred for clinical whole-exome sequencing. JAMA. 2014;312:1870–9.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the patients and their families who participated in this study. We also thank the other members of the Division of Human Genetics and the Division of Genomic Diagnostics at the CHOP. Funding for this work was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Human Genome Research Institute UO1-HG006546 as part of the Clinical Sequencing Exploratory Research Consortium (to I.D.K., N.B.S., and J.W.P.) and National Institute of General Medical Sciences (5T32GM008638 to M.H.L.). No funding body participated in study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation, writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

DISCLOSURE

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, and provide a link to the Creative Commons license. You do not have permission under this license to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sheppard, S., Biswas, S., Li, M.H. et al. Utility and limitations of exome sequencing as a genetic diagnostic tool for children with hearing loss. Genet Med 20, 1663–1676 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-018-0004-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-018-0004-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Differential genetic diagnoses of adult post-lingual hearing loss according to the audiogram pattern and novel candidate gene evaluation

Human Genetics (2022)

-

Identification of autosomal recessive nonsyndromic hearing impairment genes through the study of consanguineous and non-consanguineous families: past, present, and future

Human Genetics (2022)

-

Genetic epidemiology of autoinflammatory disease variants in Indian population from 1029 whole genomes

Journal of Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (2021)

-

Exome sequencing in infants with congenital hearing impairment: a population-based cohort study

European Journal of Human Genetics (2020)

-

A Practical Approach to Genetic Testing for Pediatric Hearing Loss

Current Otorhinolaryngology Reports (2020)