Abstract

The genetic background of lupus nephritis (LN) has not been completely elucidated. We performed a case-only study of 2886 SLE patients, including 947 (33%) with LN. Renal biopsies were available from 396 patients. The discovery cohort (Sweden, n = 1091) and replication cohort 1 (US, n = 962) were genotyped on the Immunochip and replication cohort 2 (Denmark/Norway, n = 833) on a custom array. Patients with LN, proliferative nephritis, or LN with end-stage renal disease were compared with SLE without nephritis. Six loci were associated with LN (p < 1 × 10−4, NFKBIA, CACNA1S, ITGA1, BANK1, OR2Y, and ACER3) in the discovery cohort. Variants in BANK1 showed the strongest association with LN in replication cohort 1 (p = 9.5 × 10−4) and proliferative nephritis in a meta-analysis of discovery and replication cohort 1. There was a weak association between BANK1 and LN in replication cohort 2 (p = 0.052), and in the meta-analysis of all three cohorts the association was strengthened (p = 2.2 × 10−7). DNA methylation data in 180 LN patients demonstrated methylation quantitative trait loci (meQTL) effects between a CpG site and BANK1 variants. To conclude, we describe genetic variations in BANK1 associated with LN and evidence for genetic regulation of DNA methylation within the BANK1 locus. This indicates a role for BANK1 in LN pathogenesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a complex autoimmune disease predominantly affecting women in their child-bearing age. Lupus nephritis (LN) constitutes one of the main clinical challenges in patients with SLE and is a cause of significant morbidity and mortality. LN occurs in 15–55% of patients with SLE with a higher incidence in Asian and African populations [1, 2]. Proliferative glomerulonephritis, defined as class III/IV according to the histopathological classification systems ISN/RPS 2003 or WHO, is considered the most severe form of nephritis and requires immunosuppressive treatment with glucocorticoids and mycophenolate mofetil or cyclophosphamide [3, 4]. Despite improved treatment regimens, approximately 10% of all LN patients develop end-stage renal disease (ESRD) [1].

The genetic background to SLE has been thoroughly investigated through candidate gene and genome-wide association studies. To date, more than 100 SLE risk loci have been identified that explain a significant proportion of SLE heritability [5]. Less is known about the genetic background of LN. Distinct genetic factors associated with LN in patients of different ethnicities have been reported [2]. Some of the known SLE susceptibility genes, which function in the immune system, seem to be also associated with LN. Still, more renal-specific genes predispose specifically to LN. Genetic variants in HLA-DR, ITGAM, FCGR, IRF5, TNIP1, STAT4, and TNFSF4 have been associated with both SLE per se and with LN, whereas APOL1, PDGFRA, and HAS2 have been identified in LN specifically [6]. Genetic variants in STAT4 have been proposed to associate with SLE and LN in general, and with a more severe subtype of LN and renal failure [7, 8].

Epigenetic regulation, such as DNA methylation, has been proposed to be of importance in SLE pathogenesis [9]. Epigenetic mechanisms affect gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence. Hypomethylation of type I interferon-induced genes in patients with SLE has been well established [10, 11]. In LN, a role of epigenetic regulation has been suggested, e.g., the type I interferon regulator gene IRF7 is differently methylated between SLE patients with and without renal involvement [12]. This case-only study aimed to further elucidate the genetic and epigenetic background to LN and its subtypes using data from three large SLE cohorts.

Results

Patient characteristics

Patient characteristics are described in Table 1. In all cohorts, patients with LN were more often men, younger at diagnosis, and presented with a higher number of American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria than SLE patients without LN. Renal biopsy data were available for the discovery and replication cohort 1, where proliferative nephritis was the most common class of nephritis (173/278, 62% in the discovery cohort and 65/118, 55% in replication cohort 1). Among LN patients with available renal function data at follow-up, 38/290 (13%) in the discovery cohort and 48/216 (22%) in replication cohort 1 proceeded to ESRD.

Genetic association analysis

Discovery cohort

First, we compared allele frequencies between SLE patients with (n = 377) and without LN (n = 714) in the discovery cohort. The strongest signals of association with LN were found for four highly-linked single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) close to the Nuclear Factor of Kappa Light Polypeptide Gene Enhancer in B Cells Inhibitor, Alpha (NFKBIA) gene (top SNP rs12433012, p = 1.3 × 10−5, OR: 0.54, 95% CI: 0.41–0.71). A total of 139 SNPs were associated with p < 0.001. Associations with p < 1 × 10−4 were observed for SNPs in Calcium Voltage-Gated Channel Subunit Alpha1 S (CACNA1S), Integrin Subunit Alpha 1 (ITGA1), B Cell Scaffold Protein with Ankyrin Repeats 1 (BANK1), Olfactory Receptor Family 2 Subfamily Y Member 1 (OR2Y1) and Alkaline Ceramidase 3 (ACER3) (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 1).

Manhattan plot displaying results from the association analysis of 112,815 SNPs in 377 patients with lupus nephritis (LN) and 714 SLE without nephritis in the discovery cohort. The negative logarithm of the p-value is plotted against the chromosomal location of the tested variants. Genes with SNPs associated with LN with p < 1 × 10−4 are denoted.

We then analyzed the association between genetic variants and the subgroup proliferative nephritis, comparing LN patients with proliferative nephritis (n = 173) versus SLE without nephritis (n = 714). Associations with p < 1 × 10−4 were found between proliferative nephritis and SNPs in ITGA1 and BANK1 (Supplementary Table 2). Finally, analysis was performed comparing LN patients who had reached ESRD (n = 38) versus SLE without nephritis (n = 714). An association between LN patients with ESRD and rs2763321 in the Membrane Palmitoylated Protein 7 (MPP7) gene was found (p = 7.4 × 10−6) (Supplementary Table 3).

Replication cohort 1

All SNPs reaching a p-value of <0.001 in the analyses of LN (nSNPs = 139), proliferative nephritis (nSNPs = 198), or ESRD (nSNPs = 182) versus SLE without nephritis in the discovery cohort were analyzed in replication cohort 1. In the analysis of LN (n = 216) versus SLE without nephritis (n = 746), the strongest signal of association was identified for a SNP in BANK1 (p = 9.5 × 10−4) (Table 2). When analyzing proliferative nephritis (n = 65) and ESRD (n = 48) versus SLE without nephritis, no associations with p < 0.001 were found (data not shown).

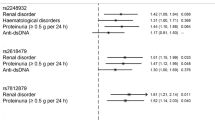

Meta-analyses were performed using the results from the discovery and replication cohort 1 for LN, proliferative nephritis, and ESRD versus SLE without nephritis, respectively. In the LN meta-analysis, the strongest signal of association was found for several highly-linked SNPs in BANK1 (pmeta = 3.3 × 10−7 for the top SNP rs4699261), passing the Bonferroni-corrected p-value of <1.0 × 10−6 (Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 1). A regional association plot of the BANK1 region based on the analysis of LN versus SLE without nephritis in the discovery cohort, revealed a cluster of highly linked SNPs in the first intron region (Fig. 2).

In the meta-analysis of proliferative nephritis versus SLE without nephritis, associations were observed for several SNPs in BANK1 (top SNP rs6856202, pmeta = 1.3 × 10−5, r2 = 0.53 to rs4699261, Supplementary Table 4. Finally, a meta-analysis of ESRD versus SLE without nephritis found an association for rs12573804 in long intergenic non-protein coding RNA 1515 (LINC01515) on chromosome 10 (pmeta = 9.6 × 10−6, Supplementary Table 5).

Replication cohort 2

Ten SNPs from genes with the highest signals of association to LN in the discovery cohort were selected and successfully genotyped in replication cohort 2, consisting of 833 patients with SLE from Denmark and Norway. In the analysis of patients with LN (n = 354) versus SLE without nephritis (n = 479), no significant associations between these SNPs and LN were found (Supplementary Table 6). However, BANK1 SNP rs4699259 (r2 = 0.98 to rs4699261) was associated with LN with p = 0.052 and the same direction of effect (OR: 0.80, 95% CI: 0.64–1.0) as in the discovery cohort and replication cohort 1. A random-effect meta-analysis was performed using the results for rs4699259 from all three cohorts. In this meta-analysis, the association between LN and BANK1 was strengthened (pmeta = 2.2 × 10−7).

Case-control analysis

To further corroborate the association between LN and BANK1, the top SNP rs4699261 was investigated in a case-control analysis of patients from the discovery cohort with SLE (n = 1091) and stratified for SLE without nephritis (n = 714) and LN (n = 377) versus healthy controls (n = 2707), respectively. An association with SLE was found with p = 2.0 × 10−4 and OR 0.80 (95% CI: 0.71–0.90). In the analysis of SLE without nephritis versus controls, no association with BANK1 was found (p = 0.28, OR 0.93, 95% CI: 0.81–1.07). When comparing LN patients with controls, a stronger association with BANK1 SNP rs 4699261 could be determined with p = 6.0 × 10−7 and OR 0.62 (95% CI: 0.52–0.75).

Analysis of genetic regulation of DNA methylation by LN associated variants

Next, we aimed to investigate whether the effects of LN-associated genetic variants from this and previous studies, could be mediated through changes in DNA methylation. A methylation quantitative trait loci (meQTL) analysis was performed in whole blood from 180 LN patients from the discovery cohort against the genotypes. The strongest meQTL effects were identified in Integrin Subunit Alpha M (ITGAM) and B lymphocyte kinase (BLK). However, genetic variants in these genes were not significantly associated with LN in this study (data not shown). In the BANK1 locus, we identified meQTL effects between CpG site cg01116491 and several SNPs (top SNP rs6856202, pmeQTL = 6.1 × 10−4, r2 = 0.52 to rs4699259, Supplementary Table 7). The SNP rs6856202 major allele (A) is the risk allele, associated with LN in the discovery cohort (p = 3.1 × 10−4) and with proliferative nephritis in the meta-analysis of discovery and replication cohort 1 (p = 1.3 × 10−5) (Supplementary Tables 1, 4). LN patients homozygous for the risk allele (A) showed hypermethylation at CpG site cg01116491 compared with LN patients heterozygous (GA) or homozygous for the non-risk allele (G) (Fig. 3). Association with DNA methylation levels was also found for another block of SNPs in the BANK1 locus (top SNP rs7683892, r2 = 0.57 to rs4699259). However, we did not observe a direct effect of the top SNP rs4699259 with the level of DNA methylation at any BANK1 CpG site (data not shown).

Box plot of the BANK1 meQTL rs6856202−cg01116491. SNP genotypes at rs6856202 are shown on the x-axis, methylation-beta values of CpG site cg01116491 are shown on the y-axis. The major allele (A) of rs6856202 is associated with increased methylation at cg01116491 (pmeQTL = 6.0 × 10−4) in whole blood from patients with LN. The major allele (A) is the risk allele for LN in the discovery cohort and displayed the highest signal of genetic association to proliferative nephritis in the meta-analysis of discovery and replication cohort 1 (pmeta = 1.3 × 10−5). Box plot center lines indicate medians, box boundaries indicate first and third quartile, and whiskers extend to data points located within 1.5 times the length of interquartile range from the median.

Functional annotation of associated variants

To further investigate the potential functional role of the identified variants, public databases were queried. In Open Targets Genetics [13], SNP rs4699259 is shown to be an expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL) for BANK1 in lymphoblastoid cell lines, where the risk allele (C) is associated with upregulated BANK1 mRNA expression (β = 0.20, p = 5.8 × 10−10). Furthermore, in the GTEx portal, rs4699259 is proposed to be an eQTL for BANK1 expression in subcutaneous adipose tissue, and in HaploReg v4.1, rs4699262 (in perfect LD with rs4699259, r2 = 1.0) is shown to be an eQTL for BANK1 expression in the blood (p = 5.7 × 10−5) [14].

Discussion

Here we present associations between SNPs in BANK1 and LN in the hitherto most extensive case-only study, comprising nearly 3000 patients with SLE of European ancestry. Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first time BANK1 SNPs have been associated with the severe form of proliferative nephritis. We also present novel evidence for genetic regulation of DNA methylation within the BANK1 locus in patients with LN. The top SNP is an eQTL for BANK1, where the risk allele is associated with upregulated BANK1 mRNA expression in lymphoblastoid cell lines.

To investigate potential functional effects of BANK1 variants, we performed a meQTL analysis using whole blood from patients with LN. The BANK1 top SNP associated with proliferative nephritis displayed a meQTL effect, where LN patients homozygous for the risk genotype showed hypermethylation at CpG site cg0111649. The CpG site cg01116491 is located in a gene body region approximately 3300 bp downstream of the transcription start site of BANK1. Hypermethylation in gene body regions can be an indication of increased gene expression [15, 16]. This meQTL site is in a region that overlaps with histone modification mark H3K36me3 in B cells, and H3K36me3 is associated with actively transcribed gene bodies [17]. These findings could indicate an effect of the risk genotype for BANK1 in upregulating BANK1 expression, mediated by epigenetic regulation.

Searching databases, SLE-associated variants in BANK1 are eQTLs in multiple tissues, where the risk alleles associate with increased BANK1 expression [18]. Interestingly, different eQTL effects for BANK1 SNP rs4637409 (r2 = 0.75 to rs4699261) in B cells from healthy males and females have been described [19]. In males, the SLE risk allele was associated with increased expression of the SLC39A8 gene, located downstream of BANK1, whereas the eQTL effect was opposite in females. Sex-biased eQTL effects are intriguing since LN is more common in male patients with SLE, and this topic warrants further investigations.

BANK1 is a B cell adaptor protein primarily expressed in mature B cells and, to a lesser extent, in myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells [18, 20]. Upon B cell receptor activation, BANK1 enhances calcium mobilization, becomes tyrosine phosphorylated, and can promote Lyn-mediated phosphorylation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors (IP3R) [20]. BANK1 is 785aa in its full-length (FL) form and has a smaller isoform lacking the second exon (D2 isoform), which encodes a Toll/IL-1 receptor domain (TIR) [21]. The SLE risk variant rs10516487 in exon 2, first described by Kozyrev et al., is causing a nonsynonymous substitution (R61H) and correlates with decreased splicing of exon 2 and a higher expression of the FL isoform containing the TIR domain [21, 22]. BANK1 is functionally linked to Toll-like receptor (TLR) pathways with downstream activation of transcription factor NFκB and IFN regulatory factors, promoting B cell activation and inflammation, and prominent features of SLE [23,24,25,26].

Genetic variations in BANK1 have convincingly been associated with SLE and replicated in multiple ethnicities [18, 21, 27,28,29,30]. The often investigated exon 2 non-synonymous variant rs10516487 (R61H), displays associations with SLE of approximately the same magnitude in all studied ethnicities (≈OR 0.70 referring to the minor allele), despite differences in minor allele frequency among control populations. Martinez-Bueno et al. reported a trans-ethnic mapping of BANK1 associations with SLE in Europeans and African−Americans [18]. The associated markers covered the same regions in both populations but haplotype blocks differed, with greater diversity among African−Americans. We conclude that although there are trans-ethnic differences in haplotype structure, the association between SLE and BANK1 variants is robust across ethnicities.

Stratifying SLE patients for the immunologic, hematological, or renal ACR criteria or presence of anti-dsDNA antibodies, more robust associations with BANK1 have been reported compared with analyses of all SLE patients versus controls [28, 31]. Several autoimmune diseases report associations with BANK1, including systemic sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, autoimmune thyroid disease, and germinal center formation in Sjögren’s syndrome minor salivary glands, suggesting BANK1 as a general autoimmunity susceptibility gene [32,33,34,35]. The exon 2 variant rs10516487 (r2 = 0.75 to rs4699259) was only weakly associated with LN in our case-only analysis of the discovery cohort (OR 0.76, 95% CI 0.61–0.95, p = 0.015, data not shown) and did not pass our filtering criteria for analysis in replication cohorts 1 and 2. The exon 2 variant may confer risk for SLE per se, whereas the intron 1 variants here described having an impact on disease severity such as LN, particularly the more severe subtype proliferative nephritis.

While LN case-control analyses inherently also are SLE case-control studies, we chose to perform and replicate a case-only study comparing SLE patients with or without LN in an attempt to refine the genetic contribution to LN. To further determine if the BANK1 association was primarily with LN and not SLE per se, we performed a post hoc case-control analysis of the discovery cohort comparing SLE, SLE without nephritis, and LN versus controls, respectively. We found the association with BANK1 to be stronger in the analyses, LN versus controls and LN versus SLE without nephritis (Table 2), than the SLE case-control and SLE without nephritis-control analyses, and conclude the association with BANK1 is mainly with LN. Chung et al. performed a case-only meta-analysis of three genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and found an association with LN within the PDGF receptor-α (PDGFRA) gene locus [36]. Unfortunately, this gene locus was not covered on the Immunochip used in this study. In our previous study, the STAT4 SNP rs7582694 was associated with LN with severe renal insufficiency (glomerular filtration rate <30 mL/min/1.73m2) [7]. The outcome of severe renal insufficiency was not analyzed in the current study. However, STAT4 SNP rs10181656 (r2 = 1.0 to rs7582694) displayed a trend for association with ESRD (p = 0.07, data not shown).

Interestingly, in concordance with previous observations, the highest signals of association with LN were assigned to genes outside the MHC locus [7, 37]. The conclusion is that although variants in the MHC locus confer the strongest genetic risk for SLE, other gene regulatory regions are of importance in the development of LN. The genetic risk for LN has also been assessed by calculating genetic risk scores (GRS). Reid et al. concluded that SLE patients with a high GRS were at increased risk of developing renal disorder, including proliferative nephritis and ESRD [38]. Webber et al. found a high GRS to be associated with proliferative nephritis and a greater risk for LN in childhood than in adult SLE [37]. Both of these studies included BANK1 variants in their GRS.

The importance of B cells in LN pathogenesis and inflammation is not well defined. Infiltrating B cells can be found in more than half of LN biopsies, mostly in the tubulointerstitial compartment [39]. Upregulated mRNA expression of BANK1 has been detected in renal biopsies from LN patients, mainly in the tubulointerstitial compartment [36]. Together with the genetic association between BANK1 and LN presented here, a role for B cells in LN pathogenesis is suggested. Single-cell RNA sequencing of samples from LN biopsies has determined different B cell clusters with upregulated genes defining an activated B cell state [40]. Despite this, trials with anti-B cell therapy in LN have shown varying success [41, 42]. The use of genetic and other biomarkers may improve patient stratification for treatment decisions in the future [43].

The strengths of this study are the replication of our findings in large cohorts of well classified SLE patients with homogenous genetic backgrounds. Renal biopsy data could be retrieved from two of the cohorts, making it possible to assess the subgroup with proliferative nephritis. The availability of DNA methylation data from our discovery cohort adds an epigenetic layer to our genetic findings. A limitation is a cross-sectional design, where follow-up time varied between patients. Some SLE patients without nephritis may develop LN in the future and the subtype may also change during follow-up. This study only involved SLE patients of European ancestry, and BANK1 associations to LN in other ethnicities remain to be studied.

To conclude, we here demonstrate an association between BANK1 and LN in three large cohorts of SLE patients of European ancestry. Furthermore, evidence of genetic control of methylation levels within the BANK1 locus was observed. The upregulation of BANK1 gene expression in renal biopsies from LN patients indicates a functional role of BANK1, although the exact mechanisms in LN pathogenesis need to be further elucidated.

Subjects and Methods

Patients

Discovery cohort

The discovery cohort included 1155 Swedish SLE patients, out of which 1091 passed genotype quality control (QC). The patients originated from Stockholm (n = 346), Linköping (n = 172), Uppsala (n = 188), Lund (n = 153), and Umeå (n = 232), and fulfilled either the 1982 ACR criteria for SLE or had a biopsy confirmed LN in the presence of anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA) or anti-double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) antibodies, according to the SLICC classification [44, 45]. Renal biopsy histopathology was available from 278/377 (73.7%) patients. The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committees, and the patients gave written informed consent.

Replication cohort 1

Replication cohort 1 included 962 patients after QC, with SLE from the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Lupus Genetics project [46]. European ancestry was determined using STRUCTURE, including individuals being ≥85% European [47]. All patients completed an extensive questionnaire and the SLE diagnosis was confirmed by medical record review according to the ACR criteria [45]. Renal biopsy histopathology was available from 118/216 (54.6 %) patients. The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committees, and the patients gave written informed consent.

Replication cohort 2

Replication cohort 2 consisted of 854 patients with SLE from Denmark and Norway, all of self-reported European origin and fulfilling ≥4 ACR criteria for SLE [45]. After QC, 833 patients remained for analysis. The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committees, and the patients gave written informed consent. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Controls

Healthy blood donors were recruited as previously described [48]. After QC, 2707 healthy controls remained.

Genotyping and quality control

The discovery cohort and controls were genotyped on the Illumina Infinium Immunochip (San Diego, California, USA), containing 196,524 SNPs covering the major autoimmune diseases [49]. Genotyping was performed at the SNP&SEQ Technology Platform, part of the National Genomics Infrastructure (NGI) at Uppsala University, Sweden. SNP-based QC filters were call rate >95%, Hardy−Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) p > 1 × 10−6, and MAF > 0.05. Sample QC included principal component analysis (PCA) performed on 1000 Genomes Project data, where individuals of non-European ancestry were removed, cryptic relatedness analysis with the removal of second-degree relatives or closer, and autosomal heterozygosity with the removal of individuals with anomalously high (F ≤ −0.1) or low (F ≤ 0.1) heterozygosity. The sample call rate was set to 96%. After QC, 112,815 SNPs remained for analysis.

Replication cohort 1 was genotyped on the Immunochip in four different laboratories. The following QC was performed on the genotyping data from each lab in the following order prior to merging data from all four labs: (1) Removal of individuals with <80% complete genotyping, (2) removal of SNPs with <95% call rate, and (3) removal of individuals with <95% complete genotyping. Duplicates and first-degree relatives were removed by identity-by-descent analysis [50]. Ancestry outliers with substantial non-European ancestry were identified via EIGENSTRAT (>4SD in top three principal components) and excluded [51]. SNPs with HWE p < 1 × 10−5 (based on European controls) were removed. After QC, 128,263 SNPs remained for analysis.

A total of 15 SNPs with association to LN in the discovery cohort (all p < 0.0002) (Supplementary Table 1) and annotated in or nearby a gene were selected for genotyping in replication cohort 2. One SNP per gene in NFKBIA, CACNA1S, PALLD, LOC10537883, ENPP2, and PKHD1L1 and two SNPs in BANK1 and ITGA1 were successfully genotyped. Replication cohort 2 was genotyped using the iPLEX chemistry on a MassARRAY system (Agena Bioscience). QC included a minimum SNP and individual call rate of 90%. Variants with differential missingness (p < 0.01) or HWE (p < 0.01, in controls) were excluded. Ten SNPs and 833 patients passed QC and had available information on LN occurrence according to ACR criteria (Denmark n = 547, Norway n = 286) [45].

The regional association plot was generated in LocusZoom software (Fig. 2). Linkage disequilibrium (LD) r2 values were derived from the 1000 Genomes Project CEU population (Northern Europeans from Utah) and extracted from the LDlink service [52] using the LDlinkR package [53] (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Methylation quantitative trait loci (meQTL) analysis

We performed a cis-meQTL analysis investigating DNA methylation levels in whole blood from LN patients from the discovery cohort (n = 180 with DNA methylation data available) against the genotypes of SNPs with a nominal p-value <0.001 in LN versus SLE without nephritis analysis in the discovery cohort (n = 110 SNPs) and SNPs in genes that had been previously associated to LN (n = 482, n = 592 SNPs in total) [6]. DNA methylation data were generated on the HM450k methylation array, normalized and quality controlled as previously described [11]. All CpG sites located within a 100 kb flanking region of these SNPs were included, and methylation levels were tested in PLINK for genotype association in LN patients assuming an additive model.

Definitions

LN was defined according to the ACR nephritis criteria or a biopsy confirmed LN in the presence of ANA or anti-dsDNA antibodies, according to the SLICC classification [44, 45]. Biopsies were classified according to the WHO or ISN/RPS 2003 classification systems [3]. Proliferative nephritis was defined as class III or IV nephritis in either classification system. Data on renal function were collected from patient charts at the latest available time of sampling, and glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was calculated using the modification of diet in renal disease study (MDRD) formula [54]. Patients with LN and ESRD, defined as either dialysis or transplantation, were identified.

Statistical analysis

Allele frequencies were compared between patients with LN, proliferative nephritis, and ESRD respectively, using SLE patients without LN as a control group. Logistic regression was performed in PLINK software v 1.07 [50]. Sex and disease duration were included as covariates.

All SNPs with a nominal p-value of <0.001 in LN versus SLE without nephritis (n = 139 SNPs), proliferative nephritis versus SLE without nephritis (n = 198 SNPs), and ESRD versus SLE without nephritis (n = 182 SNPs) analyses in the discovery cohort were selected for analysis in replication cohort 1. Logistic regression was performed in PLINK, adjusting for sex, disease duration, and the first principal component for population stratification. Meta-analyses of the discovery cohort and replication cohort 1 were performed for LN, proliferative nephritis, and ESRD versus SLE without nephritis patients, using all SNPs that passed QC in both cohorts. Random-effects meta-analysis p-values are reported. A Bonferroni corrected p-value of <1.0 × 10−6 adjusting for 48,000 independent SNPs on the Immunochip was considered significant.

In replication cohort 2, logistic regression was performed in PLINK for patients with LN (n = 354) versus SLE without nephritis patients (n = 479). Sex and disease duration were used as covariates. A meta-analysis was performed using the logistic regression analyses of LN versus SLE without nephritis patients from all three cohorts. Random-effects meta-analysis p-values are reported.

The top SNP from association analysis of LN vs SLE patients without LN in the discovery cohort was further investigated in case-control analyses of patients with SLE and LN vs healthy controls (n = 2707), respectively. Allele frequencies were compared between patients and controls in a logistic regression analysis with age and sex as covariates.

References

Mahajan A, Amelio J, Gairy K, Kaur G, Levy RA, Roth D, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus, lupus nephritis and end-stage renal disease: a pragmatic review mapping disease severity and progression. Lupus. 2020;29:1011–20.

Lanata CM, Nititham J, Taylor KE, Chung SA, Torgerson DG, Seldin MF, et al. Genetic contributions to lupus nephritis in a multi-ethnic cohort of systemic lupus erythematous patients. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0199003.

Weening JJ, D’Agati VD, Schwartz MM, Seshan SV, Alpers CE, Appel GB, et al. The classification of glomerulonephritis in systemic lupus erythematosus revisited. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:241–50.

Fanouriakis A, Kostopoulou M, Cheema K, Anders HJ, Aringer M, Bajema I, et al. Update of the Joint European League Against Rheumatism and European Renal Association-European Dialysis and Transplant Association (EULAR/ERA-EDTA) recommendations for the management of lupus nephritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;2020:713–23.

Langefeld CD, Ainsworth HC, Cunninghame Graham DS, Kelly JA, Comeau ME, Marion MC, et al. Transancestral mapping and genetic load in systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Commun. 2017;8:16021.

Iwamoto T, Niewold TB. Genetics of human lupus nephritis. Clin Immunol. 2017;185:32–39.

Bolin K, Sandling JK, Zickert A, Jonsen A, Sjowall C, Svenungsson E, et al. Association of STAT4 polymorphism with severe renal insufficiency in lupus nephritis. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e84450.

Taylor KE, Remmers EF, Lee AT, Ortmann WA, Plenge RM, Tian C, et al. Specificity of the STAT4 genetic association for severe disease manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000084.

Hedrich CM. Epigenetics in SLE. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2017;19:58.

Absher DM, Li X, Waite LL, Gibson A, Roberts K, Edberg J, et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis of systemic lupus erythematosus reveals persistent hypomethylation of interferon genes and compositional changes to CD4+ T-cell populations. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003678.

Imgenberg-Kreuz J, Carlsson Almlof J, Leonard D, Alexsson A, Nordmark G, Eloranta ML, et al. DNA methylation mapping identifies gene regulatory effects in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:736–43.

Coit P, Renauer P, Jeffries MA, Merrill JT, McCune WJ, Maksimowicz-McKinnon K, et al. Renal involvement in lupus is characterized by unique DNA methylation changes in naive CD4+ T cells. J Autoimmun. 2015;61:29–35.

Ghoussaini M, Mountjoy E, Carmona M, Peat G, Schmidt EM, Hercules A, et al. Open Targets Genetics: systematic identification of trait-associated genes using large-scale genetics and functional genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:D1311–D1320.

Ward LD, Kellis M. HaploReg v4: systematic mining of putative causal variants, cell types, regulators and target genes for human complex traits and disease. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D877–881.

Arechederra M, Daian F, Yim A, Bazai SK, Richelme S, Dono R, et al. Hypermethylation of gene body CpG islands predicts high dosage of functional oncogenes in liver cancer. Nat Commun. 2018;9:3164.

Jones PA. Functions of DNA methylation: islands, start sites, gene bodies and beyond. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:484–92.

Bernstein BE, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, Costello JF, Ren B, Milosavljevic A, Meissner A, et al. The NIH Roadmap Epigenomics Mapping Consortium. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:1045–8.

Martinez-Bueno M, Oparina N, Dozmorov MG, Marion MC, Comeau ME, Gilkeson G, et al. Trans-ethnic mapping of BANK1 identifies two independent SLE-risk linkage groups enriched for co-transcriptional splicing marks. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:2331.

Linden M, Ramirez Sepulveda JI, James T, Thorlacius GE, Brauner S, Gomez-Cabrero D, et al. Sex influences eQTL effects of SLE and Sjogren’s syndrome-associated genetic polymorphisms. Biol Sex Differ. 2017;8:34.

Yokoyama K, Su IhIH, Tezuka T, Yasuda T, Mikoshiba K, Tarakhovsky A, et al. BANK regulates BCR-induced calcium mobilization by promoting tyrosine phosphorylation of IP(3) receptor. EMBO J. 2002;21:83–92.

Kozyrev SV, Abelson AK, Wojcik J, Zaghlool A, Linga Reddy MV, Sanchez E, et al. Functional variants in the B-cell gene BANK1 are associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2008;40:211–6.

Kozyrev SV, Bernal-Quiros M, Alarcon-Riquelme ME, Castillejo-Lopez C. The dual effect of the lupus-associated polymorphism rs10516487 on BANK1 gene expression and protein localization. Genes Immun. 2012;13:129–38.

Georg I, Diaz-Barreiro A, Morell M, Pey AL, Alarcon-Riquelme ME. BANK1 interacts with TRAF6 and MyD88 in innate immune signaling in B cells. Cell Mol Immunol. 2020;17:954–65.

Troutman TD, Hu W, Fulenchek S, Yamazaki T, Kurosaki T, Bazan JF, et al. Role for B-cell adapter for PI3K (BCAP) as a signaling adapter linking Toll-like receptors (TLRs) to serine/threonine kinases PI3K/Akt. Proc Natl Acad. Sci USA. 2012;109:273–8.

Wu YY, Kumar R, Haque MS, Castillejo-Lopez C, Alarcon-Riquelme ME. BANK1 controls CpG-induced IL-6 secretion via a p38 and MNK1/2/eIF4E translation initiation pathway. J Immunol. 2013;191:6110–6.

Wu YY, Kumar R, Iida R, Bagavant H, Alarcon-Riquelme ME. BANK1 regulates IgG production in a lupus model by controlling TLR7-dependent STAT1 activation. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0156302.

Grant SF, Petri M, Bradfield JP, Kim CE, Santa E, Annaiah K, et al. Association of the BANK 1 R61H variant with systemic lupus erythematosus in Americans of European and African ancestry. Appl Clin Genet. 2009;2:1–5.

Guo L, Deshmukh H, Lu R, Vidal GS, Kelly JA, Kaufman KM, et al. Replication of the BANK1 genetic association with systemic lupus erythematosus in a European-derived population. Genes Immun. 2009;10:531–8.

Ramirez-Bello J, Jimenez-Morales S, Montufar-Robles I, Fragoso JM, Barbosa-Cobos RE, Saavedra MA, et al. BLK and BANK1 polymorphisms and interactions are associated in Mexican patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Inflamm. Res. 2019;68:705–13.

Guan M, Yu B, Wan J, Zhang X, Wu Z, Zhong Q, et al. Identification of BANK1 polymorphisms by unlabelled probe high resolution melting: association with systemic lupus erythematosus susceptibility and autoantibody production in Han Chinese. Rheumatology. 2011;50:473–80.

Chung SA, Taylor KE, Graham RR, Nititham J, Lee AT, Ortmann WA, et al. Differential genetic associations for systemic lupus erythematosus based on anti-dsDNA autoantibody production. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1001323.

Muhali FS, Song RH, Wang X, Shi XH, Jiang WJ, Xiao L, et al. Genetic variants of BANK1 gene in autoimmune thyroid diseases: a case-control association study. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes. 2013;121:556–60.

Orozco G, Abelson AK, Gonzalez-Gay MA, Balsa A, Pascual-Salcedo D, Garcia A, et al. Study of functional variants of the BANK1 gene in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:372–9.

Reksten TR, Johnsen SJ, Jonsson MV, Omdal R, Brun JG, Theander E, et al. Genetic associations to germinal centre formation in primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1253–8.

Rueda B, Gourh P, Broen J, Agarwal SK, Simeon C, Ortego-Centeno N, et al. BANK1 functional variants are associated with susceptibility to diffuse systemic sclerosis in Caucasians. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:700–5.

Chung SA, Brown EE, Williams AH, Ramos PS, Berthier CC, Bhangale T, et al. Lupus nephritis susceptibility loci in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:2859–70.

Webber D, Cao J, Dominguez D, Gladman DD, Levy DM, Ng L, et al. Association of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) genetic susceptibility loci with lupus nephritis in childhood-onset and adult-onset SLE. Rheumatology. 2020;59:90–98.

Reid S, Alexsson A, Frodlund M, Morris D, Sandling JK, Bolin K, et al. High genetic risk score is associated with early disease onset, damage accrual and decreased survival in systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79:363–9.

Steinmetz OM, Velden J, Kneissler U, Marx M, Klein A, Helmchen U, et al. Analysis and classification of B-cell infiltrates in lupus and ANCA-associated nephritis. Kidney Int. 2008;74:448–57.

Arazi A, Rao DA, Berthier CC, Davidson A, Liu Y, Hoover PJ, et al. The immune cell landscape in kidneys of patients with lupus nephritis. Nat Immunol. 2019;20:902–14.

Furie R, Rovin BH, Houssiau F, Malvar A, Teng YKO, Contreras G, et al. Two-year, randomized, controlled trial of belimumab in lupus nephritis. New Engl J Med. 2020;383:1117–28.

Rovin BH, Furie R, Latinis K, Looney RJ, Fervenza FC, Sanchez-Guerrero J, et al. Efficacy and safety of rituximab in patients with active proliferative lupus nephritis: the lupus nephritis assessment with rituximab study. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:1215–26.

Caster DJ, Powell DW. Utilization of biomarkers in lupus nephritis. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2019;26:351–9.

Petri M, Orbai AM, Alarcon GS, Gordon C, Merrill JT, Fortin PR, et al. Derivation and validation of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:2677–86.

Tan EM, Cohen AS, Fries JF, Masi AT, McShane DJ, Rothfield NF, et al. The 1982 revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1982;25:1271–7.

Thorburn CM, Prokunina-Olsson L, Sterba KA, Lum RF, Seldin MF, Alarcon-Riquelme ME, et al. Association of PDCD1 genetic variation with risk and clinical manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus in a multiethnic cohort. Genes Immun. 2007;8:279–87.

Hubisz MJ, Falush D, Stephens M, Pritchard JK. Inferring weak population structure with the assistance of sample group information. Mol Ecol Resour. 2009;9:1322–32.

Almlof JC, Alexsson A, Imgenberg-Kreuz J, Sylwan L, Backlin C, Leonard D, et al. Novel risk genes for systemic lupus erythematosus predicted by random forest classification. Sci Rep. 2017;7:6236.

Cortes A, Brown MA. Promise and pitfalls of the Immunochip. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13:101.

Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–75.

Price AL, Patterson NJ, Plenge RM, Weinblatt ME, Shadick NA, Reich D. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2006;38:904–9.

Machiela MJ, Chanock SJ. LDlink: a web-based application for exploring population-specific haplotype structure and linking correlated alleles of possible functional variants. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3555–7.

Myers TA, Chanock SJ, Machiela MJ. LDlinkR: An R package for rapidly calculating linkage disequilibrium statistics in diverse populations. Front Genet. 2020;11:157.

Levey AS, Greene T, Sarnak MJ, Wang X, Beck GJ, Kusek JW, et al. Effect of dietary protein restriction on the progression of kidney disease: long-term follow-up of the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;48:879–88.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Swedish Research Council for Medicine and Health (Dnr 521-2014-2263 to ACS, Dnr 521-2014-3954 to ES, Dnr 2016-01982 to GN and Dnr 2018-02399 to LR), the Swedish Rheumatism Association, the Swedish Society for Medical Research, Swedish Society of Medicine and the Ingegerd Johansson donation and the King Gustav V’s 80-year Foundation. DNA sequencing was performed at the SNP&SEQ Technology Platform in Uppsala, part of the National Genomics Infrastructure (NGI) Sweden, and supported by Science for Life Laboratory, the Swedish Research Council (VR-RFI), Uppsala University, and the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation. We thank Rezvan Kiani and Marianne Pettersson for biobank administration.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bolin, K., Imgenberg-Kreuz, J., Leonard, D. et al. Variants in BANK1 are associated with lupus nephritis of European ancestry. Genes Immun 22, 194–202 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41435-021-00142-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41435-021-00142-8