Abstract

Background/Objectives

Several health systems have implemented innovative models of care which share the management of patients with chronic eye diseases between ophthalmologists and optometrists. These models have demonstrated positive outcomes for health systems including increased access for patients, service efficiency and cost-savings. This study aims to understand factors which support successful implementation and scalability of these models of care.

Subjects/Methods

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 21 key health system stakeholders (clinicians, managers, administrators, policy-makers) in Finland, United Kingdom and Australia between October 2018 and February 2020. Data were analyzed using a realist framework to identify the contexts, mechanisms of action, and outcomes of sustained and emerging shared care schemes.

Results

Five key themes relating to successful implementation of shared care were identified as (1) clinician-led solutions, (2) redistributing teams, (3) building inter-disciplinary trust, (4) using evidence for buy-in, and (5) standardized care protocols. Scalability was found to be supported by (6) financial incentives, (7) integrated information systems, (8) local governance, and (9) a need for evidence of longer-term health and economic benefits.

Conclusions

The themes and program theories presented in this paper should be considered when testing and scaling shared eye care schemes to optimize benefits and promote sustainability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As the prevalence of chronic eye diseases rises [1] there is a growing demand for eye care professionals to provide examinations for detection and monitoring of disease, and improve access to interventions. Budget and workforce shortages have challenged the ability of health systems to meet demand and provide accessible and timely sight-saving treatments [2].

To improve access, multiple health systems have introduced task-sharing models of care (known as “shared care” or “collaborative care”) to manage patients with chronic eye diseases. In shared care, traditional ophthalmologist-led tasks are shared with non-medical teams [3]. Often they involve standardized eye examinations being conducted by an optometrist, nurse, or technician who partner with an ophthalmologist to inform a patient’s diagnosis and management [4,5,6]. However, the mode of delivery and level of task-sharing (including clinical decision-making) varies widely. For example, there are referral refinement schemes whereby community-based optometrists support referral triage [7,8,9]; hospital-based optometrist-led/nurse-led schemes [5], or community-based clinics whereby optometrists examine patients with ophthalmologist oversight, either direct supervision [10] or virtual review [5, 11, 12].

Extensive evaluations of various modalities—both as pilots and ongoing schemes—have demonstrated that shared care is efficient, safe, and effective. Various schemes have improved access to specialist care and increased hospital capacity [5, 10, 12, 13], reduced service duplication (i.e., diagnostic imaging) [8], improved referral targeting [7, 9] and reduced service costs [10, 12, 14]. Multiple studies have demonstrated that shared care providers who make independent clinical decisions can achieve high levels of agreement with ophthalmologists [7, 8, 10, 12, 13], and deliver reliable clinical assessments [8].

While these benefits are well-documented, fewer studies have investigated the ways these schemes are implemented, the transition from piloting to standard care, or adoption in new settings. This is useful to inform implementation and refinement in new settings, or support scaling-up of existing schemes. The realist theoretical framework can help uncover these program complexities, and identify how different circumstances generate different outcomes [15, 16]. Realist evaluations aim to understand what works, for whom, in what circumstances, to what extent, how, and why [16]. A key assumption is that programs are underpinned by theories which explain the mechanism of change (generative causation) [15].

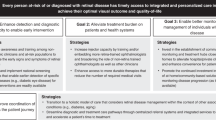

This study aims to understand the factors which support or impede implementation and scalability of shared care programs in the United Kingdom (UK), Finland and Australia. Using a realist approach [16] the contexts, mechanisms and outcomes of existing and emerging shared care schemes will be identified to inform program theories which can support broader implementation and scalability.

Methods

Setting and design

Semi-structured interviews were conducted between October 2018 and February 2020 with key health system stakeholders in the UK, Finland, and Australia. These countries were chosen because they had (1) emerging (Australia), sustained or mature shared care models of care (Finland and UK), and (2) similar health systems (universal health coverage, with public ophthalmology services being free for patients (UK, Australia) or subsidized by regulated co-payments (Finland)).

Subjects

Participants were purposely sampled from various levels of the health system to capture broad perspectives [17]; and because of their (direct or indirect) involvement in the implementation, adaptations, and ongoing delivery of services. Recruitment included:

-

(i)

Clinicians: ophthalmologists, optometrists, nurses, ophthalmic technicians;

-

(ii)

Managers and administrators: service managers, nurse/optometrist managers; quality improvement and data managers, departments, and hospital leads;

-

(iii)

Governance: regulatory or peak clinical organizations; policymakers.

Prior to the interviews, participants were given an invitation (email or in-person), study information, and signed consent forms. Initial sampling targeted clinicians, often ophthalmologists or optometrists, with introductions made through professional networks of the study investigators. Several participants were sought for their expertise or involvement in formally evaluated and published shared care schemes. Additional stakeholders were nominated by enrolled participants during interviews, either by request of the study team or prompted by the participant. Interviews occurred initially in Finland, followed by the UK, and Australia.

Data collection and analysis

A semi-structured interview schedule (Supplementary File 1) was adapted using Pawson and Tilley’s “Would it work here?” [18]. Interviews were conducted by three investigators (BF, BA, HL) either in person or by phone for 30 min to 1.5 h. During interviews, prompts informed by published shared care evaluations acted as “program theories” that were tested and validated by participants. The interviewers repeated emerging themes to the participant to allow opportunity for validation of emerging program theories through “theory gleaning” [17]. All interviews included questions regarding unintended outcomes. Interviews were audio-recorded and notes taken. Audio-files were transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription company or one of the investigators (BF) and checked for accuracy prior to analysis. Several participants were invited to review or respond to selected quotes and themes for further theory refinement [17].

Coding and analyses were conducted using NVIVO (12, QSR International 2018). Transcripts were reviewed iteratively, as available. An initial coding framework of 21 codes was derived from the themes and six program theories reported in Baker et al.’s Systematic realist review [6], and were validated using deductive reasoning. The initial coding framework was used by two investigators (BF, BA) to duplicate code four [4] interviews, representing different stakeholder groups from the UK and Finland. An additional 16 codes were identified from the interviews using inductive reasoning. Three investigators (BA, BF, HL) discussed the coding and discrepancies, and came to a consensus on a final coding framework. Preliminary themes and relationships between codes was also recorded. One investigator (BF) used the final coding framework to analyze the remaining 17 transcripts, adding 2 additional codes based on emerging ideas. Interviews involving an investigator as a participant were coded by a second investigator (BA) for rigor.

Realist evaluation framework

Emerging themes and selected quotes relating to the implementation and scalability of shared care models were identified by one investigator (BF) and presented to the remainder of the study team (LK, BA, AW, HL) at iterative stages for discussion and further refinement. Once themes were established, coding and quotes were reviewed in-depth to generate the contexts-mechanisms-outcomes (C-M-O) configurations for each theme.

Research team and reflexivity

The research team was multidisciplinary with expertise in ophthalmology (AW), optometry (LK), health economics (HL, BA, BF), public health (all), health administration (BA, BF) and qualitative research (HL, BF, LK). Two members of the study team were considered key stakeholders because they were directly involved in the delivery of a shared care pilot in Australia (AW, BF) and the UK (AW) and were invited to participate. To minimize any bias of being stakeholder-investigators, these interviews were conducted by two external investigators (BA, HL). Four members of the study team had also been involved in evaluations of an emerging collaborative (shared) care model in Australia (BF, BA, LK, AW) [10, 12].

Results

Participants

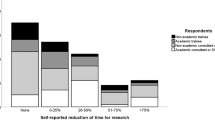

Twenty-one interviews were conducted (Finland—9; UK—5; Australia—7) with participants representing multiple levels of the health system (Table 1). Most participants were clinicians (ophthalmologists, nurses, or optometrists) typically with dual responsibility in management, governance, education, or information technology. Many had initiated shared care, with some having 30-years’ experience; while others learned by participation in ongoing schemes. Several participants had been involved in more than one scheme, including movement across care settings and countries.

Types of shared care

The design, funding mechanisms, and the types of chronic eye diseases examined differed across the settings (Table 1). These schemes included hospital-based, hospital-outreach, or community-based clinics; national screening programs; and informal private partnerships. In Finland and the UK, some had tiered approaches whereby multiple schemes were implemented in one hospital. Shared care was mostly implemented as a formal program and funded publicly through the national health insurance, either through direct employment of staff (e.g., hospital clinicians), or reimbursement using a fee-for-service (e.g., community optometrists). Often patients would receive eye care with no or little co-payment. Australia also had reports of informal arrangements between independent optometrists and ophthalmologists, where funding would come from a mix of patient out-of-pocket (co-payment) fees and government reimbursements.

Themes

Nine themes relating to the implementation (n = 5) and scalability (n = 4) of shared care models were derived. Key illustrative quotes for themes are presented in Table 2. The realist context-mechanisms-outcome configurations which inform the program theories are presented in Table 3.

Implementation themes

Access blocks, safety concerns, and clinician driven solutions

This depicted the rationale for initiating the innovation (shared care), and how these models gained traction. Across settings, change was often initiated by clinicians, usually ophthalmologists, but also by nurses, optometrists, and an endocrinologist. Generally, ophthalmologists had observed negative clinical outcomes (vision loss/blindness) in their patients occurring as a direct consequence of being unable to access overburdened ophthalmology clinics. In several settings, clinical safety was the catalyst for change, prompting administrators to look toward clinicians for solutions. (Table 2, quote 1a)

Redistribution of Health Care resources, to optimize skill sets, with minimal investment

Redistribution of existing healthcare resources by reorganizing (and upskilling) multi-disciplinary teams through task-sharing arrangements promoted efficiency. For example, fundus photographs taken by technicians, clinical decisions by nurses/optometrists, and support staff transferring patient information. Ophthalmologists generally provided supervision through direct oversight or virtual (store-and-forward) review. Ophthalmologists spent less patient-facing time with the lower risk patients, meaning releasing them to spend more time with complex and advanced patients. Participants often reported that existing resources were rearranged, rather than increased. (Table 2 quote 2b)

Interdisciplinary Trust needed to shift clinical responsibility

Motivation and trust were needed to build inter-disciplinary relationships to shift the clinical responsibility from the ophthalmologists to nurses or optometrists. The C-M-O configurations presented in Table 3 demonstrate the various ways that trust was established. Examples include formal training or more organically through daily interactions. Trusting relationships were thought to lead to better clinical decision-making, with a reinforcing effect whereby improved decision-making meant ophthalmologists were more willing to release responsibility. (Table 2, quote 3c)

Generating buy-in from decision makers to sustain models of care

Services demonstrated that these models of care were effective, which in turn facilitated teams to get buy-in from decision makers. This included generating evidence on service efficiency, safety, productivity, and acceptability. Participants reported that additional change management could help the transition from pilots to sustained care pathways. For example, regular communication with stakeholders to reinforce the rationale and benefits. (Table 2, quote 4d)

Standardized care as equitable care

The use of standardized protocols/processes, care pathways, and proformas streamlined care. This ensured that patients were being managed at a clinically appropriate level. For example, ophthalmologists saw complex and advanced patients, while less-complex patients were assessed by optometrists or nurses. Standardized care was believed to give all patients an equal opportunity to care by removing barriers to access, such as cost or long wait times.

Scalability themes

Health care investment to incentivise and motivate

Incentives are required to motivate and encourage providers to participate and sustain the schemes. Financial incentives were essential to recognize the investments of time, infrastructure, and effort (clinical and administrative) required to deliver services. In the UK and Finland, financial incentives included fee-for-service for community providers (by hospitals), or higher duty payments. Incentives were often justified by the cost-savings accrued through task-sharing. In Australia, the financial model was not clearly developed, and lack of financial incentives available to participating clinicians was a major barrier for sustainability. Participants recognized that funding should be allocated by health departments, and recommended to extend the existing Medicare Benefits Schedule items (telehealth or integrated care) to cover store-and-forward review, or by hospitals introducing an incentive payment for participating private providers. (Table 2, quotes 6f–g)

Systems to integrate care and link providers

Health systems need to invest in information technology systems which can transfer patient information between multiple providers. Across settings, there was frustration with current systems which were described as inefficient and clunky. Specific issues were the use of multiple programs and log-ins, and information being transferred via paper and scanned documents. Participants felt that investment in integrated information systems was important for scalability as it could increase efficiency and support continuity of care. Investment in information technology should also consider systems which incorporate data analytics for improved quality control and monitoring of longer-term patient outcomes. (Table 2, quote 7h)

Localised governance and monitoring supports quality care

Governance structures and quality assurance mechanisms were required for ongoing program delivery. This covers legal and regulatory issues, program administration, membership or accreditation, ongoing safety and quality monitoring, and development of policy and guidelines. Formal governance processes were necessary when patient volume increased or when models were scaled to include more partners. There were some examples of governance structures which were guided by national clinical guidelines, however more often governance and processes were determined locally. (Table 2, quotes 8i–k)

A shift to find evidence of longer-term health and economic outcomes

There is a need to generate evidence of the longer-term health and economic outcomes of these models. Current evidence generally assumed that improved capacity and access leads to better health outcomes. However, longer-term outcomes are not yet understood. Focus should shift to the impact on vision loss and a more wholistic perspective of economic outcomes when patient volume increases; including impacts on access to other eye care services, and health outcomes for patients with more advanced disease, or ocular co-morbidities. (Table 2, quote 9l)

Discussion

Informed by broad health system stakeholder experiences, this study has drawn evidence from shared eye care interventions at different stages of maturity and within various health system contexts to build an understanding of what factors influence implementation and transition of pilots into scaled and sustained programs. The use of the realist approach meant testing and validation of program theories could evolve our knowledge of how these program work [16]. The implementation themes presented in this paper were reported consistently across settings, informing overarching theories to explain why these programs work. Within complex health systems, it has been suggested that innovations with obvious effect will be more readily adopted [19]. In this study it was universally recognized that the impetus for change was the high demand for eye care due to the growing population of patients with chronic eye diseases and adverse vision outcomes due to delayed access. This led to health system administrators to seek sustainable and acceptable solutions (task-sharing) to increase capacity and improve access. However, the implementation of these solutions varied greatly across and within countries. By adopting a realist approach, this study has been able to establish the context-mechanism-outcome configurations (Tables 1 and 3) to provide insight into what works and how this is achieved across contexts [16].

When it came to scalability, these themes were informed by stakeholder’s experiences of problems/solutions; not only from sustained models of care but also the perceived barriers for broader uptake in systems where these schemes are still emerging. Participants in all settings strongly believed that health system investment was needed to scale services, notably through remuneration and information technology models. These investments would ensure longevity of outcomes and productivity gains.

This study built on theories reported by Baker et al. [6] which describe the success and failures of similar shared eye care in the UK. Several theories were validated. For example, participants across settings validated the effectiveness of task-sharing (Theme 2; Baker et al. Theory 1), the importance of genuine local partnerships for implementation (Theme 3 and 8; Baker et al. Theory 2), and the benefits of standardizing care (Theme 5; Baker et al. Theory 3). However, Baker et al.’s [6] program theories were founded on studies which report mostly on outcomes and effectiveness of interventions, and were less focussed on implementation processes and contextual factors (Baker et al. Theory 6—Barriers and enablers). Thus, in this study, an important methodological component was inductive analysis to refine and generate new program theories to explain aspects of program implementation. In this study, clinician leadership (Theme 1) and interdisciplinary trust (Theme 3) were mechanisms needed to effectively facilitate task-sharing and shifting of responsibility as reported in Baker et al.’s Theory 1.

Task-sharing in health care is not new and has been used widely in other disciplines to address some of the same obstacles seen in eye care; and can be useful in low income countries where health care resources are scarce [20]. In Australian and UK settings, a prominent example of scaled shared care are antenatal programs which involve GPs (or midwives) and obstetricians. These programs are standard practice in most public hospitals and national clinical guidelines ensure fidelity remains. However, these programs can be adapted locally to provide responsive care (e.g., tiered approaches such as midwifery group practice or GP-obstetrician programs [21].) In another example, Kemp et al. [22] suggest that scaling (national and international) of a maternal and child health program was achieved by allowing local adaptations while maintaining program fidelity. They liken this to baking a basic cake (core components) and adding recipe variations (local adaptions) to adjust flavor.

Similar core components exist in shared care initiatives used in eye care and other health disciplines. This includes supervision, training or upskilling workforce [20, 22]; well-defined scope of practice [20, 23]; protocols [20, 22, 23]; and service integration [21, 22, 24]. Information technology is recognized as an essential component for team communication [23, 24]. Within eye care, large-scale diabetic retinopathy screening programs in the UK rely on teleophthalmology (store-and-forward) to transfer information across providers [25]. In India, electronic medical records that interlace through a three-tiered eyecare network (primary care, secondary clinics and tertiary eye hospitals) are able to capture data and imaging for large populations over time. Furthermore, digitization of health information allows real-time analytics which can support quality control and research to measure longer-term health outcomes [26]. In this current study, several participants reported investment into local IT systems. One UK example is a web-based patient record (New Medica) which has facilitated almost 25,000 virtual consultations across multiple clinics. By embedding automated quality checks and real-time feedback for optometrists, Wright et al. were able to demonstrate improvements in patient care [27]. However, Sim et al. [25] report that lack of integration with a nationally accessible electronic health system is a known barrier to uptake of teleophthalmology in the UK. In our study, participants were unsatisfied with current IT systems due to lack of integration and inability to extract meaningful data. Thus, longer-term health and economic outcomes cannot be efficiently monitored; and services were unable to make informed decisions on how to allocate resources to achieve the best outcomes [28].

Information technology is not the only challenge. Resistance to change from both organizations and providers is regularly cited as a key concern across disciplines for the successful uptake of shared care [20, 22, 25]. Participants in this study suggested change management strategies were needed, including regular communication and engagement for teams, external clinicians, and stakeholders; motivation (and incentives) for providers; and involving the right people, such as clinicians, to lead the change. Other studies recommend that effective leadership [20, 25] or local champions are needed to gain “buy-in” [22] and drive change. However, team culture and power imbalances should be addressed to support uptake [19, 24]. In this study, interdisciplinary trust evolved organically through daily interactions and training. One Australian study examining interprofessional relationships of shared eye care providers found that trust is established by regular contact or co-location of providers [23], however in another study too much oversight and scrutiny of optometrists work resulted in diminished levels of trust [29]. Thus, for broader implementation, pre-planning should consider including change management strategies to facilitate adoption.

Study limitations

This study has several limitations. First, it does not capture the concurrent experiences of piloting and implementation of shared care models, and relied on retrospective accounts from various stakeholders, some of whom had been involved in the initial pilots, program modifications, and ongoing implementation. However, the schemes in Finland and UK were in place for many years which provides valuable insight into sustainability. Second, being a qualitative study, the sample is limited to 21 participants from three countries and does not reflect the experiences of all shared eye care programs, particularly the barriers for programs that have been disbanded when unsuccessful. The context-mechanism-outcomes configurations are based on participant perceptions of events or ability to recall, thus may not cover all aspects of local implementation. However, the sample was purposely selected to reflect a wide range of by experts who have been involved in piloting, program evolution, evaluation and the development of policy, guidelines, and education.

Conclusions

Using a realist approach, this study has identified nine key factors relating to the implementation and scalability of shared eye care programs in the UK, Finland, and Australia. Overall, implementation is supported by clinician-led solutions, rearranging multidisciplinary teams, building inter-disciplinary trust, generating local buy-in, and using standardized care protocols. Scalability will require investment from broader health systems to support financial incentives to motivate providers and integrated information systems. There was a preference for schemes to be governed locally, allowing for flexible implementation. However, evidence is still needed for longer-term health and economic outcomes when scaled. Shared eye care is necessary to tackle the growing demands for eye care services, and for these programs to be effective, equitable, high quality and sustainable, findings should be systematically addressed.

Summary

What was known before

-

There is a growing demand for chronic eye care services to detect, monitor, and treat disease.

-

Shared care between ophthalmologists and optometrists can increase access for patients, and improve efficiency and cost-savings for health systems.

What this study adds

-

Successful implementation of shared care is enabled with clinician leadership, redistribution of resources, trust, monitoring, and standardized care.

-

Scalability of shared care can be supported through incentives, integrated systems, governance, and evidence of longer-term benefits.

-

Health system and policy stakeholders perspectives and the realist framework assist in understanding implementation and scalability of shared eye care schemes.

-

These findings can guide eye care professionals in planning and expansion of shared eye care in new settings.

Data availability

Deidentified participant data are available from authors upon reasonable request. Access to any data will require ethical review and approval from the UNSW HREC, and may require investigators to collect additional individual consent from participants for further use of data.

References

Flaxman SR, Bourne RR, Resnikoff S, Ackland P, Braithwaite T, Cicinelli MV, et al. Global causes of blindness and distance vision impairment 1990–2020: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5:e1221–34.

Resnikoff S, Lansingh VC, Washburn L, Felch W, Gauthier T-M, Taylor HR, et al. Estimated number of ophthalmologists worldwide (International Council of Ophthalmology update): will we meet the needs? Br J Ophthalmol. 2020;104:588–92.

International Council of Ophthalmology. ICO position on training teams to meet public needs. 2018. https://www.icoph.org/downloads/ICO-Position-Training-Teams.pdf.

White A, Goldberg I, Australian New Zealand Glaucoma Interest Group the Royal Australian New Zealand College of Ophthalmologists. Guidelines for the collaborative care of glaucoma patients and suspects by ophthalmologists and optometrists in Australia. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2014;42:107–17.

Tuulonen A, Kataja M, Syvänen U, Miettunen S, Uusitalo H. Right services to right patients at right time in right setting in Tays Eye Centre. Acta Ophthalmol. 2016;94:730–5.

Baker H, Ratnarajan G, Harper RA, Edgar DF, Lawrenson JG. Effectiveness of UK optometric enhanced eye care services: a realist review of the literature. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2016;36:545–57.

Bourne R, French K, Chang L, Borman A, Hingorani M, Newsom W. Can a community optometrist-based referral refinement scheme reduce false-positive glaucoma hospital referrals without compromising quality of care? The community and hospital allied network glaucoma evaluation scheme (CHANGES). Eye. 2010;24:881.

Spry P, Spencer I, Sparrow J, Peters T, Brookes S, Gray S, et al. The Bristol Shared Care Glaucoma Study: reliability of community optometric and hospital eye service test measures. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83:707–12.

Huang J, Yapp M, Hennessy MP, Ly A, Masselos K, Agar A, et al. Impact of referral refinement on management of glaucoma suspects in Australia. Clin Exp Optom. 2019;103:675–83

Ford BK, Angell B, Liew G, White AJ, Keay LJ. Improving patient access and reducing costs for glaucoma with integrated hospital and community care: a case study from Australia. Int J Integr Care. 2019;19:1–9.

Violato M, Dakin H, Chakravarthy U, Reeves B, Peto T, Hogg R, et al. Cost-effectiveness of community versus hospital eye service follow-up for patients with quiescent treated age-related macular degeneration alongside the ECHoES randomised trial. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011121.

Tahhan N, Ford B, Angell B, Liew G, Nazarian J, Maberly G, et al. Evaluating the cost and wait-times of a task sharing model of care for diabetic eye care: a case-study from Australia. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e036842.

Keenan J, Shahid H, Bourne RR, White AJ, Martin KR. Cambridge community Optometry Glaucoma Scheme. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2015;43:221–7.

Coast J, Spencer IC, Smith L, Spry PG. Comparing costs of monitoring glaucoma patients: hospital ophthalmologists versus community optometrists. J Health Serv Res Policy. 1997;2:19–25.

Wong G, Westhorp G, Manzano A, Greenhalgh J, Jagosh J, Greenhalgh T. RAMESES II reporting standards for realist evaluations. BMC Med. 2016;14:96.

Pawson R, Tilley N. Realistic evaluation. London: Sage; 1997.

Manzano A. The craft of interviewing in realist evaluation. Evaluation. 2016;22:342–60.

Pawson R, Tilley N. Realist evaluation: the magenta book guidance notes. London: Cabinet Office; 2004. p. 2008.

Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q. 2004;82:581–629.

Ashengo T, Skeels A, Hurwitz EJ, Thuo E, Sanghvi H. Bridging the human resource gap in surgical and anesthesia care in low-resource countries: a review of the task sharing literature. Hum Resour Health. 2017;15:77.

Donnolley NR, Chambers GM, Butler-Henderson KA, Chapman MG, Sullivan E. A validation study of the Australian maternity care classification system. Women Birth. 2019;32:204–12.

Kemp L. Adaptation and fidelity: a recipe analogy for achieving both in population scale implementation. Prev Sci. 2016;17:429–38.

Long JC, Blakely B, Mahmoud Z, Ly A, Zangerl B, Kalloniatis M, et al. Evaluation of a hospital-based integrated model of eye care for diabetic retinopathy assessment: a multimethod study. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e034699.

Barr N, Vania D, Randall G, Mulvale G. Impact of information and communication technology on interprofessional collaboration for chronic disease management: a systematic review. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2017;22:250–7.

Sim DA, Mitry D, Alexander P, Mapani A, Goverdhan S, Aslam T, et al. The evolution of teleophthalmology programs in the United Kingdom: beyond diabetic retinopathy screening. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2016;10:308–17.

Das AV, Kammari P, Vadapalli R, Basu S. Big data and the eyeSmart electronic medical record system—an 8-year experience from a three-tier eye care network in India. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020;68:427

Wright HR, Diamond JP. Service innovation in glaucoma management: using a web-based electronic patient record to facilitate virtual specialist supervision of a shared care glaucoma programme. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015;99:313–7.

Tuulonen A, Salminen H, Linna M, Perkola M. The need and total cost of Finnish eyecare services: a simulation model for 2005–2040. Acta Ophthalmol. 2009;87:820–9.

O’Connor PM, Harper CA, Brunton CL, Clews SJ, Haymes SA, Keeffe JE. Shared care for chronic eye diseases: perspectives of ophthalmologists, optometrists and patients. Med J Aust. 2012;196:646–50.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the stakeholders who freely shared their time and expertise to participate in this study.

Funding

The lead author (BF) was supported by an Australian Research Training Program PhD scholarship; and additionally, was awarded a travel bursary from the Western Sydney Local Health District Board in 2018 to undertake an international study tour of eye hospitals in the United Kingdom and Finland to conduct participant recruitment and data collection. BA is supported by an NH&MRC Emerging Leadership Grant (GNT2010055). Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BF is primary author of this manuscript and was responsible for study design, data collection, coding and analysis, interpretation of findings, and drafting of the manuscript. BA and HL contributed to data coding and analysis, interpretation of findings, and drafting of the final manuscript. AW and LK contributed to the study design, interpretation of findings, and drafting of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study received ethical approval from the University of NSW Human Ethics Advisory Panel (Reference HC180288).

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ford, B., Angell, B., Liu, H. et al. Implementation and scalability of shared care models for chronic eye disease: a realist assessment informed by health system stakeholders in Finland, the United Kingdom, and Australia. Eye 37, 2934–2945 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-023-02444-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-023-02444-9