Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the potential association between uveitis and an increased risk of developing inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study by interrogating data from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database entered between January 1, 2001 and December 31, 2013 to identify uveitis patients and age- and gender-matched controls. The cumulative incidence rates of subsequent IBD in the two groups were compared. The adjusted hazard ratio (HR) of IBD related to uveitis was generated by a multivariate cox regression model after adjustment for hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidaemia, obesity and smoking. Furthermore, the HRs of the Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) IBD subtypes were calculated separately.

Results

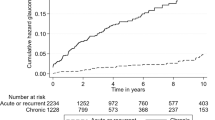

A total of 198,923 subjects with uveitis and 397,846 controls were enroled. The mean age of the cohort was 47.7 ± 18.9 years. A significantly higher cumulative incidence of IBD was found in the uveitis group than in controls (4.13% vs. 1.48%, p < 0.0001). Under univariate cox regression analysis, uveitis patients had a significantly higher risk of IBD (HR = 1.47; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.43–1.52, p < 0.0001). The association remained significant in the multivariate regression model, with an adjusted HR of 1.44 (95% CI: 1.39–1.49, p < 0.0001). Moreover, in subgroup analysis, uveitis was significantly associated with an increased risk of Crohn’s disease (adjusted HR = 1.49; 95% CI: 1.44–1.54), but not with ulcerative colitis (adjusted HR = 1.03; 95% CI: 0.92–1.15).

Conclusions

Patients with uveitis are at significantly greater risk of developing IBD than individuals without uveitis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Uveitis is inflammation of the uveal tract of the eye. Subtypes are categorized by anatomic sites of involvement, and include anterior (iris and ciliary body), posterior (choroid and retina), intermediate (pars plana), and panuveitis (generalized inflammation). Clinical manifestations may include ocular pain, photophobia, blurred vision, and eventual visual loss. Diagnosis is established by slit-lamp examination or indirect ophthalmoscopy, which detect cellular infiltrates in the anterior chamber or vitreous body. Uveitis is often associated with systemic disorders, such as spondyloarthropathy, psoriasis, and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [1,2,3,4].

IBD encompasses the chronic idiopathic autoimmune enteropathies of Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). Clinical features include rectal bleeding, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, anorexia, and low-grade fever. Ulceration, stricture, and fistula formation may be found during endoscopy [5,6,7,8,9]. Ocular presentations comprise episcleritis, scleritis, uveitis, corneal diseases, conjunctivitis, and retinitis [10,11,12]. Previous studies have reported a 2–5% prevalence of uveitis in IBD patients [13,14,15]. The pathogenesis of uveitis in the setting of IBD is not fully understood. Hypothetical aetiologies include immune complex-mediated or delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions to antigens shared by the colon and extra-colonic organs [16, 17].

Most investigations regarding the relationship between uveitis and IBD have been cross-sectional studies that have evaluated the prevalence of uveitis among IBD patients [13, 14, 18,19,20]. A limited number of cohort studies have examined the incidence of IBD in uveitis patients. Veloso et al., in a prospective population-based study in Portugal, found that iritis/uveitis subsequently occurred in 6.4% of CD patients and in 4.6% of UC patients during a 20-year follow-up period [21]. The Swiss IBD Cohort Study conducted by Biedermann et el. revealed uveitis prevalence rates of 11.1% and 5.6% in CD and UC patients, respectively, either before or during the follow-up period [22]. However, these studies lacked of control groups, obviating a direct comparison of uveitis rates between IBD patients and the general population. While the aforementioned studies evaluated the frequency of uveitis among IBD patients, to the best of our knowledge, only one study has investigated the risk of subsequent IBD among uveitis patients. Aletaha et al. interrogated a large commercial health insurance claims database and found the risk of incident IBD was significantly higher in uveitis patients than in the non-uveitis group, with a hazard ratio (HR) of 5.0 [23]. Furthermore, uveitis may precede the diagnosis of IBD [13, 22]. The identification of uveitis as a potential indicator of IBD risk may be valuable to enable the identification of a susceptible population that may benefit from targeted surveillance to facilitate early detection and timely treatment of IBD. Consequently, it is reasonable to define the risk of incident IBD in uveitis patients.

We hypothesized that uveitis patients may have a higher risk of incident IBD than those without uveitis. An interrogation of the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) in Taiwan could identify large number of uveitis patients as well as matched controls. By using a long study period, we could evaluate IBD as a long-term outcome in our study cohort. In addition, we divided the IBD outcome into CD and UC subtypes to analyse subtype-specific associations with uveitis.

Materials and methods

Data source

The Taiwan National Health Insurance programme covers the healthcare services of ~99% of Taiwan’s residents. The NHIRD, which is maintained by the National Health Research Institutes (NHRI) of Taiwan, is a collection of all registration files and claims data for all ambulatory and in-hospital patients in Taiwan. Diagnoses are registered using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes. We elected to evaluate patient data entered between January 1, 2002 and December 31, 2013. To protect patient privacy, the NHRI has encrypted the names of patients, health care providers, and medical institutions with unique and anonymous identifiers before data are released for research purposes [24]. Consequently, according to the rules of the Institutional Review Board, our study protocol was exempt from an informed consent requirement. This study was approved by the ethical committee of Yang-Ming University Hospital (2015A018).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

This was a retrospective cohort study using the Taiwan NHIRD. We first selected patients with uveitis (ICD-9-CM codes 363.0x, 363.1x, 363.2x, 364.1x, 364.2x, 364.3x, 360.11, 360.12, 360.14, 364.01, 364.02, 364.04, 364.05). The diagnosis of uveitis was confirmed by ophthalmologists. The date of the first uveitis claim was defined as the index date. Exclusion criteria were: (1) uveitis diagnoses before January 1, 2001 and after December 31, 2013; and (2) IBD diagnosed before the index date. We also randomly selected individuals who had never received a diagnosis of uveitis as a control group. The index date of the controls was defined by the date of enrolment. A diagnosis of IBD before the index date was an exclusion criterion for the control group. To remove the bias caused by group differences, the uveitis group and the control group were matched 1:2 on age, gender, and index year (the year of index date).

Definition of outcome

The two groups were evaluated to compare their cumulate incidence rates of subsequent IBD. IBD, including CD (ICD-9-CM codes 555.x) and UC (ICD-9-CM codes 556.x) diagnosed by gastroenterologists. The diagnosis of IBD entails a constellation of clinical investigations that includes obtaining a medical history, physical examination, laboratory testing, radiologic imaging, and endoscopy with biopsy [25].

Statistical analysis

The demographic/clinical characteristics of the uveitis and control groups were compared by the two-sample t-test for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables. A Cox regression model was used to estimate the HR for the occurrence of IBD according to each variable in the univariate and multivariate analyses [26]. Covariates adjusted in the regression analysis were age; gender; and relevant comorbidities; including diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, and smoking [6]. These comorbidities were included as time-dependent variables to avoid immortal time bias [27]. Subsequently, we divided IBD into CD and UC and applied multivariate cox regression separately to derive the adjusted HRs. All statistical operations were performed using the SAS statistical package, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). A p value <0.05 was regarded statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

A total of 596,769 subjects included 198,923 in the uveitis group and 397,846 controls. The mean age of the overall cohort was 47.7 years, with a standard deviation of 18.9 years. Males accounted for a slightly higher proportion than females (54.8% vs. 45.2%). The two groups were well-matched for age and gender. The mean follow-up period of the uveitis and control groups were similar, with 6.01 years compared to 6.03 years (p = 0.102), respectively. As for the prevalence of comorbidities, we identified significant differences between the two groups in hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidaemia, obesity, and smoking (all p < 0.0001). All comorbidities were more prevalent in the uveitis group. During the study period, the cumulative incidence of IBD was 4.13% in the uveitis group, which was significantly higher than among controls (1.48%) (p < 0.0001) (Table 1).

Estimates of HRs for IBD using Cox models

The HRs of IBD during the 13-year study period calculated with univariate and multivariate Cox regression models was displayed in Table 2. In the univariate analysis, uveitis, age, female gender, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidaemia, obesity, and smoking all carried a significantly higher risk of developing IBD. The unadjusted HR related to uveitis in the univariate analysis was 1.47 (95% CI: 1.43–1.52, p < 0.0001). After adjustment for age, gender, and comorbidities, uveitis was still significantly associated with a higher risk of IBD (adjusted HR = 1.44, 95% CI: 1.39–1.49, p < 0.0001). In addition, female gender, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, and smoking remained significant risk factors for IBD (all p < 0.0001) in the multivariate analysis. Hypertension had the highest association with incident IBD (adjusted HR = 2.41; 95% CI: 1.89–3.08) (Table 2).

Subgroup analysis (CD and UC)

We further divided the outcome of IBD into two subgroups, CD and UC, in the multivariate cox regression analyses. Figure 1 shows the adjusted HRs for UC and CD related to uveitis, evaluated separately in the multivariate cox regression. The adjusted hazard for developing CD was significantly higher in patients with uveitis compared to controls (adjusted HR = 1.49; 95% CI: 1.44–1.54). However, the risk of acquiring UC did not reach statistical significance (adjusted HR = 1.03; 95% CI: 0.92–1.15). (Fig. 1).

Discussion

This 13-year population-based study using the Taiwan NHIRD identified a significantly higher cumulative incidence of IBD in the uveitis group compared to age- and gender-matched controls. After adjusting possible confounders in a multivariate cox regression, uveitis still increased the risk of incident IBD significantly. When the outcomes of CD and UC were analysed separately, uveitis was significantly associated with incident CD, but not UC.

The incidence of uveitis in Taiwan has increased recently [28]. The disease burden of IBD has also grown over the past decades. Numerous studies have reported an increasing incidence of IBD in the United States, Europe, Africa, South America, and Asia, including Taiwan [29,30,31]. As a cause of substantial morbidity and cost to the health system, IBD must become an issue over the next decade [32].

The mean age (47.7 years) and slight male predominance of our uveitis group (Table 1) are similar to the findings of Hwang’s study in Taiwan and Siak’s study in Singapore [28, 33]. However, uveitis is more female-predominant in Western countries [29, 34]. Uveitis-associated systemic diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, sarcoidosis, and ankylosing spondylitis may have different sex ratios. Varying prevalence rates of these systemic diseases between particular populations might lead to dissimilar sex ratios of uveitis [34, 35]. Our finding of significantly higher prevalence rates of hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidaemia, and obesity among uveitis patients is similar to those of previous studies that revealed associations between uveitis and these comorbidities [36, 37]. The increased prevalence of smoking in our uveitis group might reflect the upregulation of inflammatory factors and Th17 cell expansion [38, 39] induced by cigarette smoke.

One of our main findings was a significantly increased risk of developing IBD in the uveitis group in both the univariate and multivariate Cox regression models (Table 2). Aletaha et al. interrogated a population-based database in the United States and found that uveitis significantly increased the risk of incident IBD [23]. Our study design was similar to that of Aletaha et al. by using an age- and gender-matched control group. However, our study further adjusted confounders, such as comorbidities in the statistical analyses; thus, the impact of uveitis to IBD derived in our study was more likely to be a real phenomenon.

One of the strengths of our study was access to the comprehensive NHIRD, in which demographic data, diagnoses, examinations, and therapies are recorded accurately. In our healthcare system, the National Health Administration routinely checks medical charts to ensure that patients have correct diagnoses and to confirm compatibility with claims data. By using validated diagnoses of comorbidities that were adjusted in the multivariate Cox regression analysis, we further found hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, and smoking to be significantly associated with IBD. Huang’s study in Taiwan also found that an IBD cohort had a significantly higher prevalence of hypertension than controls [40]. However, Yarur’s study in the United States found opposite results; IBD patients were less likely to have hypertension and dyslipidaemia [41]. This inconsistency may have resulted from differences in ethnicity or environmental factors. Discrepant results regarding the association of smoking and IBD have also been observed in previous studies [42,43,44].

The association between uveitis and IBD is not fully understood. Das et al. suggested that shared epitopes of the intestinal mucosa and uvea contribute to pathogenesis [45]. Uveitis and IBD have also been considered to be in the same disease category, such as in the spondyloarthropathies, which are associated with manifestations of ankylosing spondylitis, uveitis, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and IBD [46, 47]. Another hypothesis emphasizes common gene expression patterns; HLA genotypes; interleukin, cytokine, and chemokine profiles; and cross-reactive antigens in both uveitis and IBD [48]. A strength of our study is the investigation of the association of uveitis not only with IBD, but also with its CD and UC subtypes. Our finding of a higher association of uveitis with CD compared to UC (Fig. 1) is consistent with previous reports from Switzerland, Portugal, and Italy [19, 21, 22]. The causes of the stronger association of uveitis with CD are unclear, but may be related to differences in the underlying pathogenesis pathways of CD and UC, which are still incompletely understood. Although CD and UC might be triggered by similar combinations of environmental factors, immune dysregulation, and microbial dysbiosis in genetically susceptible individuals [49,50,51,52], they differ in their clinical presentations and immunologic profiles, implying that they are different diseases. For example, CD is associated with increased T-helper (Th) 17 cellular activity [53], while UC is features an aberrant Th2 response [54]. Differences in pathogenesis might affect the associations of uveitis with CD or UC. A limitation of our study is the lack of laboratory data in the NHIRD regarding immunologic factors and genetics. Further studies are needed to elucidate underlying pathogenic mechanisms and to address host genetics and immunologic responses.

Conclusions

Our study disclosed an association between uveitis and an increased risk of incident IBD. Further analyses revealed a significant association between uveitis and CD, but not between uveitis and UC. The large case number in our database provided sufficient statistical power, and the cohort study design with a long follow-up period enabled clear time-sequence associations. The findings of our study have clinical and public health implications. In the clinical context, ophthalmologists should be aware of the possible risk of IBD in uveitis patients; advise the uveitis patients’ primary care physicians to screen for IBD during periodic targeted medical histories, symptom inventories, and physical exams; and recommend gastroenterology referrals, particularly for patients with gastrointestinal symptoms. From a public health perspective, policy makers are encouraged to promote screening for IBD in uveitis patients. Further basic research is warranted to elucidate the association between uveitis and IBD.

Summary

What was known before

-

Cross-sectional studies have found a 2–5% prevalence of uveitis among patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

-

Most cohort studies have investigated the incidence of uveitis among IBD patients, without control groups.

-

Only one population-based cohort study has evaluated the risk of IBD in uveitis patients and demonstrated a significantly increased incidence in the uveitis cohort compared to controls. However, confounding variables were not adjusted.

What this study adds

-

By using a 13-year nationwide controlled cohort study design, we found a significantly higher risk of incident IBD in the uveitis group.

-

In our statistical analysis, confounders were adjusted to determine a more accurate association between uveitis and IBD.

-

We further found a significant association between uveitis and Crohn’s disease, but not between uveitis and ulcerative colitis.

References

Rosenbaum JT. Uveitis in spondyloarthritis including psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Rheumatol. 2015;34:999–1002.

Egeberg A, Khalid U, Gislason GH, Mallbris L, Skov L, Hansen PR. Association of psoriatic disease with uveitis: a Danish nationwide cohort study. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1200–5.

Chi CC, Tung TH, Wang J, Lin YS, Chen YF, Hsu TK, et al. Risk of uveitis among people with psoriasis: a nationwide cohort study. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135:415–22.

Lyons JL, Rosenbaum JT. Uveitis associated with inflammatory bowel disease compared with uveitis associated with spondyloarthropathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997;115:61–4.

Greuter T, Vavricka SR. Extraintestinal manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease - epidemiology, genetics, and pathogenesis. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;13:307–17.

Argollo M, Gilardi D, Peyrin-Biroulet C, Chabot JF, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Danese S. Comorbidities in inflammatory bowel disease: a call for action. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;4:643–54.

Roberts H, Rai SN, Pan J, Rao JM, Keskey RC, Kanaan Z, et al. Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease and the influence of smoking. Digestion. 2014;90:122–9.

Vavricka SR, Brun L, Ballabeni P, Pittet V, Prinz Vavricka BM, Zeitz J, et al. Frequency and risk factors for extraintestinal manifestations in the Swiss inflammatory bowel disease cohort. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:110–9.

Vavricka SR, Schoepfer A, Scharl M, Lakatos PL, Navarini A, Rogler G. Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:1982–92.

Mintz R, Feller ER, Bahr RL, Shah SA. Ocular manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10:135–9.

Ghanchi FD, Rembacken BJ. Inflammatory bowel disease and the eye. Surv Ophthalmol. 2003;48:663–76.

Troncoso LL, Biancardi AL, de Moraes HV Jr, Zaltman C. Ophthalmic manifestations in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a review. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:5836–48.

Yilmaz S, Aydemir E, Maden A, Unsal B. The prevalence of ocular involvement in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22:1027–30.

Lanna CC, Ferrari Mde L, Rocha SL, Nascimento E, de Carvalho MA, da Cunha AS. A cross-sectional study of 130 Brazilian patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis: analysis of articular and ophthalmologic manifestations. Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27:503–9.

Felekis T, Katsanos K, Kitsanou M, Trakos N, Theopistos V, Christodoulou D, et al. Spectrum and frequency of ophthalmologic manifestations in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective single-center study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:29–34.

Das KM. Relationship of extraintestinal involvements in inflammatory bowel disease: new insights into autoimmune pathogenesis. Digestive Dis Sci. 1999;44:1–13.

Salmon JF, Wright JP, Murray AD. Ocular inflammation in Crohn’s disease. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:480–4.

Bandyopadhyay D, Bandyopadhyay S, Ghosh P, De A, Bhattacharya A, Dhali GK, et al. Extraintestinal manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease: Prevalence and predictors in Indian patients. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2015;34:387–94.

Zippi M, Corrado C, Pica R, Avallone EV, Cassieri C, De Nitto D, et al. Extraintestinal manifestations in a large series of Italian inflammatory bowel disease patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:17463–7.

Cury DB, Moss AC. Ocular manifestations in a community-based cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:1393–6.

Veloso FT, Carvalho J, Magro F. Immune-related systemic manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. a prospective study of 792 patients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1996;23:29–34.

Biedermann L, Renz L, Fournier N, Rossel JB, Butter M, Bluemel S, et al. Uveitis manifestations in patients of the Swiss Inflammatory Bowel Disease Cohort Study. Ther Adv Gastroenterol. 2019;12:1756284819865142.

Aletaha D, Epstein AJ, Skup M, Zueger P, Garg V, Panaccione R. Risk of developing additional immune-mediated manifestations: a retrospective matched cohort study. Adv Ther. 2019;36:1672–83.

Hsieh CY, Su CC, Shao SC, Sung SF, Lin SJ, Kao Yang YH, et al. Taiwan’s national health insurance research database: past and future. Clin Epidemiol. 2019;11:349–58.

Sairenji T, Collins KL, Evans DV. An update on inflammatory bowel disease. Prim Care. 2017;44:673–92.

Bradburn MJ, Clark TG, Love SB, Altman DG. Survival analysis part II: multivariate data analysis-an introduction to concepts and methods. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:431–6.

Jones M, Fowler R. Immortal time bias in observational studies of time-to-event outcomes. J Crit Care. 2016;36:195–9.

Hwang DK, Chou YJ, Pu CY, Chou P. Epidemiology of uveitis among the Chinese population in Taiwan: a population-based study. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:2371–6.

Pasvol TJ, Horsfall L, Bloom S, Segal AW, Sabin C, Field N, et al. Incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in UK primary care: a population-based cohort study. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e036584.

Chou JW, Lai HC, Chang CH, Cheng KS, Feng CL, Chen TW. Epidemiology and clinical outcomes of inflammatory bowel disease: a hospital-based study in central Taiwan. Gastroenterol Res Pr. 2019;2019:4175923.

Kaplan GG, Ng SC. Understanding and preventing the global increase of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:313–21.

Kaplan GG. The global burden of IBD: from 2015 to 2025. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12:720–7.

Siak J, Jansen A, Waduthantri S, Teoh CS, Jap A, Chee SP. The pattern of uveitis among Chinese, Malays, and Indians in Singapore. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2017;25:S81–93.

Llorenç V, Mesquida M, Sainz de la Maza M, Keller J, Molins B, Espinosa G, et al. Epidemiology of uveitis in a Western urban multiethnic population. The challenge of globalization. Acta Ophthalmol. 2015;93:561–7.

Yeung IY, Popp NA, Chan CC. The role of sex in uveitis and ocular inflammation. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2015;55:111–31.

Nien CW, Lee CY, Chao SC, Hsu HJ, Huang JY, Yeh CB, et al. Effect of uveitis on the development of keratopathy: a population-based cohort study. Investigative Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59:5053–9.

Muhammad FY, Peters K, Wang D, Lee DJ. Exacerbation of autoimmune uveitis by obesity occurs through the melanocortin 5 receptor. J Leukoc Biol. 2019;106:879–87.

Yuen BG, Tham VM, Browne EN, Weinrib R, Borkar DS, Parker JV, et al. Association between smoking and uveitis: results from the pacific ocular inflammation study. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:1257–61.

Roesel M, Ruttig A, Schumacher C, Heinz C, Heiligenhaus A. Smoking complicates the course of non-infectious uveitis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011;249:903–7.

Huang WS, Tseng CH, Chen PC, Tsai CH, Lin CL, Sung FC, et al. Inflammatory bowel diseases increase future ischemic stroke risk: a Taiwanese population-based retrospective cohort study. Eur J Intern Med. 2014;25:561–5.

Yarur AJ, Deshpande AR, Pechman DM, Tamariz L, Abreu MT, Sussman DA. Inflammatory bowel disease is associated with an increased incidence of cardiovascular events. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:741–7.

Mahid SS, Minor KS, Soto RE, Hornung CA, Galandiuk S. Smoking and inflammatory bowel disease: a meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81:1462–71.

Wang P, Hu J, Ghadermarzi S, Raza A, O’Connell D, Xiao A, et al. Smoking and inflammatory bowel disease: a comparison of China, India, and the USA. Digestive Dis Sci. 2018;63:2703–13.

Thomas T, Chandan JS, Li VSW, Lai CY, Tang W, Bhala N, et al. Global smoking trends in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review of inception cohorts. PloS One. 2019;14:e0221961.

Das KM, Vecchi M, Sakamaki S. A shared and unique epitope(s) on human colon, skin, and biliary epithelium detected by a monoclonal antibody. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:464–9.

Stolwijk C, van Tubergen A, Castillo-Ortiz JD, Boonen A. Prevalence of extra-articular manifestations in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:65–73.

Juanola X, Loza Santamaría E, Cordero-Coma M. Description and prevalence of spondyloarthritis in patients with anterior uveitis: the SENTINEL Interdisciplinary Collaborative Project. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:1632–6.

Martin TM, Smith JR, Rosenbaum JT. Anterior uveitis: current concepts of pathogenesis and interactions with the spondyloarthropathies. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2002;14:337–41.

Craven M, Egan CE, Dowd SE, McDonough SP, Dogan B, Denkers EY, et al. Inflammation drives dysbiosis and bacterial invasion in murine models of ileal Crohn’s disease. PloS One. 2012;7:e41594.

Boorom KF, Smith H, Nimri L, Viscogliosi E, Spanakos G, Parkar U, et al. Oh my aching gut: irritable bowel syndrome, Blastocystis, and asymptomatic infection. Parasit Vectors. 2008;1:40.

Hugot JP, Alberti C, Berrebi D, Bingen E, Cézard JP. Crohn’s disease: the cold chain hypothesis. Lancet. 2003;362:2012–5.

Akiho H, Yokoyama A, Abe S, Nakazono Y, Murakami M, Otsuka Y, et al. Promising biological therapies for ulcerative colitis: a review of the literature. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2015;6:219–27.

Elson CO, Cong Y, Weaver CT, Schoeb TR, McClanahan TK, Fick RB, et al. Monoclonal anti-interleukin 23 reverses active colitis in a T cell-mediated model in mice. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2359–70.

Targan SR, Karp LC. Defects in mucosal immunity leading to ulcerative colitis. Immunological Rev. 2005;206:296–305.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge National Health Insurance Research Database for all these data for research.

Funding

This work was supported by the Taichung Veterans General Hospital [grant number TCVGH-1106901B].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T-CL, Y-YC, and H-HC were involved in research design. T-CL, Y-YC, and H-HC were responsible for data collection. T-CL and Y-YC were involved in analysis and interpretation. T-CL and Y-YC were responsible for manuscript preparation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lo, TC., Chen, YY. & Chen, HH. Risk of inflammatory bowel disease in uveitis patients: a population-based cohort study. Eye 36, 1288–1293 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-021-01645-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-021-01645-4