Abstract

Aim

To describe patients with sarcoid-like granulomatous orbitopathy (SLGO), the rate of known and subsequent systemic sarcoidosis, and the treatment and outcome for the condition.

Patients and methods

Retrospective review of patients with SLGO presenting between 1990 and 2018, excluding solely lid or lacrimal drainage disease.

Results

Sixty-one patients (45 female; 74%) were identified, 54 having biopsy-proven sarcoidosis (47 orbital, 24 prior extra-orbital), and half were Afro-Caribbean. The average age at presentation was 45.3 years (range 18–78 years), with the commonest symptoms being swelling, pain and diplopia; of clinical signs, most patients (87%) had eyelid swelling, reduced motility (25%), and disease-related visual impairment (10%). Localized dacryoadenitis was present in 49/61 (21/49 bilateral) patients, and more diffuse disease in 28/61 (8/28 bilateral). Systemic involvement was found in 23 (62%) of the 37 first presenting with orbital disease. Twenty-three (38%) patients were observed and two-thirds received oral corticosteroids, with 53/61 (87%) patients having subjective and objective clinical improvement. The average follow-up was 53.4 months (range 1–315 months) and clinical recurrence occurred in 12 (20%) patients at 26.5 months (range 1–115 months) after first diagnosis.

Conclusions

Systemic sarcoidosis may be discovered in about two-thirds of patients presenting with SLGO (that tends to present with inflammatory features), but the treatment response appears similar in patients with known sarcoidosis and those with newly-diagnosed systemic disease after orbital presentation. With long-term follow-up, a third of patients have spontaneous regression of orbital disease, but 20% have recurrence after reducing or stopping systemic immunosuppression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Of unknown aetiology, sarcoidosis is a characterized by non-caseating granulomas that can involve many tissues, especially the lungs and mediastinal lymph nodes, and affects the eye or periocular tissues in 10–50% of patients [1]. It is uncertain whether purely orbital sarcoid-like granulomatous disease should be termed “sarcoidosis” [2,3,4], or whether it is a harbinger for systemic disease: to reflect this, we have used the term “sarcoid-like granulomatous orbitopathy” (SLGO)—whether the patient has solely orbital disease or has systemic involvement. Lacrimal gland is the commonest site for periocular SLGO, and involvement of other tissues—such as fat, extraocular muscles or optic nerve sheath—can occur in up to 10% of patients [2, 5,6,7,8].

We describe the presenting characteristics of patients with SLGO, the rate of known and subsequent systemic disease, as well as treatment and long-term clinical outcome. The study particularly wished to ascertain any differences between patients with, and those without, known systemic sarcoidosis at the time of orbital presentation.

Patients and methods

Patients seen between 1990 and 2018 with a diagnosis of SLGO were identified from the orbital database at Moorfields Eye Hospital, and the demographic and clinical features derived from a retrospective review of case notes; patients with solely eyelid or lacrimal drainage involvement were excluded from the study.

A diagnosis of systemic sarcoidosis was based on two or more characteristics: clinical presentation, compatible chest imaging and pulmonary function tests, elevated serum angiotensin converting enzyme (sACE), or confirmatory biopsy where needed. Plain chest X-rays were staged according to Siltzbach [9]—namely, normal (“Stage 0”), lymphadenopathy only (“Stage I”), lymphadenopathy and parenchymal disease (“Stage II”), parenchymal disease only (“Stage III”), or pulmonary fibrosis (“Stage IV”). Serum ACE titers were considered abnormal when above the upper limits of laboratory range.

Based on the systemic and orbital status, our patients fell into one of four categories: those with known systemic sarcoidosis either with (Group 1) or without (Group 2) confirmatory orbital biopsy, or those with newly-diagnosed SLGO based either on orbital biopsy (Group 3) or after systemic investigation for non-biopsied dacryoadenitis (Group 4). Diagnosis of presumptive SLGO (Group 4) was based on two or more of the following: bilateral diffuse chronic enlargement of the lacrimal glands on imaging, chest imaging compatible with sarcoidosis, elevated serum ACE, or other confirmatory systemic investigations (such as skin or bronchial biopsy).

In Group 3 patients, other causes of orbital granulomatous inflammation—such as fungal or tuberculous infection—were excluded on immunohistochemistry and serological investigations.

Data analysis was performed using SPSS v.24 (IBM Chicago, IL, USA), all tests were two-tailed, and an α-risk of 0.05 was considered clinically significant. Categorical variables were summarized as percentages and compared across treatment groups using Fisher’s exact test, whereas continuous variables were analysed using unpaired t-test or one-way analysis of variance.

The study was approved by the Ethical Review Board (MEH #164) and adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Sixty-one patients (45 female; 74%) were identified with SLGO, 54/61 having biopsy-proven disease—47 orbital biopsies (Gps. 1 and 3) and 24 prior extra-orbital biopsies (Gps. 1 and 2). The average age for orbital presentation was 45.3 years (median 44; range 18–78 years), there being no significant difference between our 4 groups (P = 0.77) (Table 1). Although only 2.9% of UK citizens are Afro-Caribbean, (https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/uk-population-by-ethnicity/national-and-regional-populations/population-of-england-and-wales/1.4) they comprised about a half of the patients with SLGO, but there was no bias for race (P = 0.46) or gender (P = 1.0) across the four groups (Table 1).

The overall average duration of orbital symptoms was 9.7 months (median 4, range 0.1–84 months), this not being different with known systemic sarcoidosis or where newly-diagnosed after orbital presentation (P = 0.61). In Group 1 and 2 patients with known systemic sarcoidosis, orbital disease presented at an average of 10 years (median 8, range 0.3–20 years) after the original diagnosis of systemic disease. Although bilateral SLGO was evident in 47/61 (77%) patients, only 25/47 had bilateral symptoms and signs. The commonest symptoms were swelling (58/61 patients; 95%), pain (14/61; 23%) and diplopia (14/61) and, of clinical signs, most patients had eyelid swelling (53/61; 87%), reduced ocular motility (15; 25%), and reduced visual functions attributable to the disease (6; 10%) (Table 1). There was 1.4 mm relative exophthalmos (median 1 mm; range 0–7 mm) in the 36 patients with clinically unilateral disease, this relative proptosis being similar in the four groups (P = 0.77) (Table 1). The proportion with prior or active uveitis was higher in those with known sarcoidosis (33% in Groups 1 and 2 combined), as compared without known sarcoidosis (11% in Groups 3 and 4) (P = 0.050) (Table 1). Dacryoadenitis was present in 49/61 (80%) patients, being bilateral in 21/49 (43%), and 17/37 (46%) patients with newly-diagnosed systemic sarcoidosis presented with dacryoadenitis (Table 2). More diffuse clinical involvement occurred in 29/61 (47%), this being unilateral in 20/29 (71%).

Orbital imaging was reviewed in 54 patients (Table 2): diffusely-enlarged lacrimal gland(s) were found in 43 (80%; 26/43 bilateral), this being commoner with newly-diagnosed systemic disease (Gps. 1 and 2 = 62%; Gps. 3 and 4 = 91%) (P = 0.015). Other tissues were involved in 29/54 cases (54%; 8/29 bilaterally)—this generally being a diffuse infiltration of fat—although 5/28 (18%) had a well-defined mass. Extraocular muscle enlargement occurred in 15/54 (28%) cases, with either fusiform enlargement or diffuse involvement from a mass alongside the muscle.

Twenty-four patients (Gps. 1 and 2) had known systemic sarcoidosis at orbital presentation, and systemic involvement was found in 23 (62%) of the 37 presenting with orbital disease (Gps. 3 and 4) (Table 1). Two-thirds of patients had pulmonary disease (significantly more where known systemic disease (P = 0.0010), upper airway disease occurred less frequently, and other sites included central nervous system (7; 11%), skin (4; 6.5%), salivary glands (2; 3%), spleen (2; 3%), and one each for heart, breast, neck and lips. Multiorgan disease was present in 16/24 (67%) of patients with known disease, but only 3/37 (8%) with newly-diagnosed SLGO (P < 0.001). Results for chest imaging were available for 47 patients, with 33 (70%) being abnormal and 30 (64%) typical for sarcoidosis: hilar lymphadenopathy (± parenchymal disease) was the commonest abnormality (Table 2). High-resolution CT confirmed the plain chest X-ray findings in four patients. Serum ACE was raised in 23/48 (48%) patients for whom titers were available, with similar rates in biopsy-proven newly-diagnosed patients (Group 3: raised sACE in 48%, with mean titer 120% of upper limits) and patients with presumed SLGO (Gp. 4: raised sACE in 50%, with mean titer 146% of upper limits).

Forty-seven patients had orbital biopsy: 43 (91%) had non-caseating granulomas, 57% chronic lymphocytic infiltrates, fibrosis in 38%, and mild necrosis in 11% (Table 3). None showed vasculitis, and stains for fungi and mycobacteria were negative in all cases.

Details of treatment were available for 60 patients, with a mean follow-up of 53.4 months (median 35, range 1–315 months). Six of 24 (25%) patients with known systemic sarcoidosis and 2/37 (5%) with newly-diagnosed SLGO were already on oral corticosteroids prior to orbital presentation (Table 4). After orbital diagnosis, 23 (38%) patients were only observed and two-thirds received oral prednisolone—31/60 (52%) starting steroids, and 6 (10%) continuing their prior dosage of steroids. Short-term (<3 months) steroids were required in 43% patients, but the others received them for a mean of 22.5 months (median 14; range 4–71 months). Steroids were started in 61% of biopsied patients (Gps.1 and 3), compared with 21% in non-biopsied patients (Gps. 2 and 4) (p = 0.006) (Table 4). Nine patients required second-line immunosuppression for 40.3 months (median 7; range 1–191 months), these including mycophenolate (six patients), hydroxychloroquine (5), methotrexate (4), and one each of cyclosporine, azathioprine and interferon (Table 4).

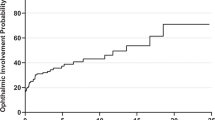

A clinical improvement—subjective and objective—was recorded in 53 (87%) patients, the results being fairly similar among four groups (P = 0.11) (Table 4). Baseline vision remained largely unchanged, apart from three patients who lost ≥3 Snellen lines—one with advanced glaucomatous optic atrophy whose extensive orbital disease improved on steroids, another without evident cause, and a third who was lost to follow-up. Twelve (20%) patients had recurrent disease at 26.5 months (median 13.5; range 1–115 months) after first orbital diagnosis, seven whilst on low-dose (1–5 mg) prednisolone (Table 4); three patients had more than one recurrence. Recurrent disease was treated by restarting or increasing steroids (eight patients), or adding second-line immunosuppressants in four.

Discussion

Although various aspects of “orbital sarcoidosis” have been reported, this investigation considers the orbital presentation in patients with known systemic disease and in those without prior diagnosis, together with their management, response to therapy and rate of recurrence. Although symptoms and signs were similar in all groups, both eyelid swelling (Table 1) and dacryomegaly on imaging (Table 2) were significantly less common in those with known systemic sarcoidosis (P = 0.030 and P = 0.015, respectively)—this probably due to prior immunosuppression in these patients. Our rates of dacryomegaly (62% in Gps. 1 and 2; 91% in Gps. 3 and 4) are higher than other reports, possibly because we excluded patients with solely eyelid or conjunctival disease, whereas they were included in the various smaller series [3, 6, 10].

Systemic involvement is reported in 8–91% of patients with “orbital sarcoidosis” [2, 3, 6, 10], and is compatible with 62% of our newly-presenting (23/37 of Gps. 3 and 4) patients having systemic disease, and an overall rate being 47/61 patients (77%). Of the 30 newly-presenting SLGO (Group 3) patients, 12 (40%) remained without systemic disease over an average follow-up of 54.8 months. Pulmonary disease was commonest, this being more so in those with known systemic disease (92%; Gps. 1 and 2) as compared with newly-diagnosed patients (46%; Gps. 3 and 4) (Table 1). Where recorded at the time of presentation with active orbital disease, sACE was raised in 23/48 (48%) patients—this being the same whether SLGO patients with known inactive systemic sarcoidosis (7/15, 47%) or newly-diagnosed SLGO patients (16/33, 48%) (Table 2). Although there might be a small bias due to 6/48 of our patients (four with known disease and two newly-diagnosed) already being on systemic steroids at the time of orbital presentation, our 48% raised sACE agrees well with reported rates of 20% [2] and 62% [3].

Granuloma formation was shown in 43/47 or our orbital biopsies; the remaining four showing chronic lymphocytic infiltration and a diagnosis of SLGO was based on known systemic sarcoidosis (two patients), and a raised sACE in the others (one with bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy). The proportion of specimens with granulomas was similar with newly-diagnosed SLGO (93%) and known systemic sarcoidosis (88%), and in lacrimal gland (94%) as compared with other orbital tissues (86%) (Table 3).

There is a paucity of reported outcomes for orbital sarcoid. Spontaneous remission occurs in up to two-thirds of systemic sarcoidosis [11], and a third of our patients had orbital improvement with observation alone—albeit recognizing that biopsy might have influenced the course of orbital disease. The remainder (62%) received systemic corticosteroids, 15% had second-line immunosuppression, and 53/56 (95%) had documented disease regression at last follow-up—this latter rate being comparable with the 70–95% control in published series [2, 3, 10]. Local recurrence occurred in 6/24 patients with known systemic sarcoid and 6/37 patients without prior history.

It should be recognized that seven patients with symptoms and signs compatible with SLGO did not have biopsy (Group 4; Table 1)—as systemic evidence and subsequent response to treatment was sufficient for a presumed diagnosis. However, if any of these patients had failed to respond according to expectation, or if they were to be considered for second-line immunosuppressants, then they would have had orbital biopsy because of the risk—albeit small—of missing an alternative or a second diagnosis.

In summary, systemic sarcoidosis is found in about two-thirds of our patients presenting with SLGO. Of these patients, those with previously-known systemic sarcoidosis tended to have somewhat milder inflammatory features—probably due to one-third being on prior immunosuppression. With long-term follow-up SLGO undergoes spontaneous regression in a third of these patients, but 20% experience recurrent disease after a reduction or stopping of systemic immunosuppression.

Summary

What is known before

-

A sarcoid-like granulomatous inflammation affecting the orbit has been reported in a few small reports.

-

This process mainly involves the lacrimal glands, but affects other tissues in 10%.

-

It remains controversial whether this is a harbinger of systemic disease and should be called “orbital sarcoidosis”.

What this study adds

-

The largest single-centre study of patients with sarcoid-like granulomatous orbitopathy (SLGO)—24 with previously-known systemic sarcoidosis and 37 presenting with orbital disease.

-

Demonstration of the marked predilection of SLGO for Afro-Caribbean patients.

-

About two-thirds of patients newly-presenting with SLGO will be found to have systemic sarcoidosis—pulmonary disease being the commonest manifestation.

-

With observation alone, SLGO improves in one-third of patients.

-

Regression occurs in most others with systemic corticosteroids alone, but 15% will need second-line immunosuppression.

-

Twenty percent will have recurrence during reduction of, or after stopping, immunosuppression.

References

Jamilloux Y, Kodjikian L, Broussolle C, Seve P. Sarcoidosis and uveitis. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:840–9.

Mavrikakis I, Rootman J. Diverse clinical presentations of orbital sarcoid. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144:769–75.

Prabhakaran VC, Saeed P, Esmaeli B, Sullivan TJ, McNab A, Davis G, et al. Orbital and adnexal sarcoidosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125:1657–62.

Mombaerts I, Reinier SO, Goldschmeding R, Koornneef L. Idiopathic granulomatous orbital inflammation. Ophthalmology. 1996;103:2135–41.

Obenauf CD, Shaw HE, Sydnor CF, Klintworth GK. Sarcoidosis and its ophthalmic manifestations. Am J Ophthalmol. 1978;86:648–55.

Collison JM, Miller NR, Green WR. Involvement of orbital tissues by sarcoid. Am J Ophthalmol. 1986;102:302–7.

Henkind P. Sarcoidosis: an expanding ophthalmic horizon. J R Soc Med. 1982;75:153–9.

Stein HA, Hendersen JW. Sarcoidosis of the orbit. Am J Ophthalmol. 1956;41:1054–6.

Siltzbach LE, James DG, Neville E, Turiaf J, Battesti JP, Sharma OP, et al. Course and prognosis of sarcoidosis around the world. Am J Med. 1974;57:847–52.

Demirci H, Christianson MD. Orbital and adnexal involvement in sarcoidosis: analysis of clinical features and systemic disease in 30 cases. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;151:1074–80.

American Thoracic Society. Statement on sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:736–55.

Acknowledgements

GER receives some funding from the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust and UCL Institute of Ophthalmology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vahdani, K., Rose, G.E. Sarcoid-like granulomatous orbitopathy—presentation, systemic involvement and clinical outcome. Eye 35, 470–476 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-020-0874-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-020-0874-4