Abstract

A thematic analysis was done to look at qualitative free-text responses to a members survey carried out by the International Glaucoma Association (IGA) in 2017. A further analysis was done on data from calls made to the IGA’s glaucoma helpline during 2018–19, including an initial investigation of cross-cutting call topics. This qualitative analysis has shed light on the complexity of patients’ information and support needs.

摘要

国际青光眼协会 (IGA) 于2017年对会员进行了问卷调研, 本文对其进行了主题分析。进一步, 我们对2018–2019年IGA的青光眼的帮助热线的数据进行了分析, 其中包括各种跨领域热线电话主题的初步调查与分析。综上, 这种定性分析揭示了青光眼患者信息需求和支持需求的复杂性。

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The International Glaucoma Association (IGA) is a registered charity that funds glaucoma research, campaigns to raise awareness and so reduce needless glaucoma blindness, and supports people to live well with glaucoma. It operates primarily in the UK and has c 4000 members.

Direct patient support services include a glaucoma telephone helpline, patient support groups and conferences, a range of information publications, and a quarterly membership magazine.

In January 2017 the IGA surveyed its members on their experience of glaucoma treatments, appointment delays, driving and the DVLA, and the IGA’s own services. Eight hundred and seventy-five completed forms were returned (a 20% response rate). The survey questions offered respondents the opportunity to provide long unrestricted answers. This type of question helps to identify some of the personal experiences, attitudes, and priorities which might underpin the scoring of other questions in the survey so were an important tool in gaining a fuller picture of what IGA members think and how they can be supported more effectively in the future.

A basic quantitative analysis was completed and published in 2017 (IGA Membership Survey Summary, August 2017). Findings were used to inform IGA service development and were shared with external agencies—for example the DVLA—to inform their own work.

In 2019 a further analysis was undertaken by EK, supervised by PL, using an iterative form of analysis. Simple ‘word counts’ suggested topics and themes that were important to respondents, and an assessment of these ‘words in context’ started a process of interpreting their use and meaning. These were further developed in a thematic mapping which demonstrates cross-cutting themes and underpinning patterns manifest across the body of responses. The IGA was keen to focus on experience of relatively current glaucoma services, so the analysis included only those who stated a definite diagnosis date within the last 10 years (n = 222). There were 17 opportunities for free-text comment in each survey and 1793 individual data points were coded.

Free-text questions of this kind pose a challenge of analysis. Responses are often too varied and complex to be simply quantified: there are no standardised answers to be collated, rather there are varied responses which need to be interpreted and synthesised. But nor does this type of data lend itself to a more traditional form of qualitative, thematic analysis; answers are typically too short (a few words or a line or two) for a theme or idea to be fully illuminated, nor are explicit topics or ideas developed across multiple answers but rather presented as a snap-shot response to a stand-alone question.

Thematic analysis

Word counts of free-text responses suggest some broad areas of interest and concern for IGA members.

It is not surprising that words describing clinical systems were amongst the thirty most frequently used (appointment, consultant, treatment, laser). Nor is it surprising that the words which reflect the consequences of glaucoma were also in this category (driving, seeing, problems). Other frequently used words (top 30) point to the significance of knowledge to this population (leaflet, ask, know, knowledge, explained) and the importance of support (needs, problems, people, supportive).

However, these broad areas disguise a more complex set of opinions and experiences. For example, words relating to information/knowledge were used by respondents in both positive and negative ways; some respondents pointing to a lack of understanding and knowledge, whilst others commented on how information had been provided, and others described seeking information for themselves. More careful consideration of how the most common words are used suggests five broad themes which capture the experiences and opinions of many IGA members.

Theme 1—anxiety associated with glaucoma

Diagnosis—especially when unexpected—was an obvious moment of anxiety for respondents, one which might have been mitigated by the provision of greater support or more information:

“I was not aware of any loss and found it difficult to believe anything was wrong. There is no support at hospital on diagnosis, I was given drops and told to use them or I’d go blind. I was absolutely terrified” (Respondent 85)

“I would have liked someone explain to me more about glaucoma and [tell me that I] can carry on life as normal. [It] was scary after being diagnosed” (R 111)

Anxiety, however, does not dissipate once the shock of diagnosis has passed and respondents pointed to concerns about future deterioration in sight, about difficulties with NHS provision, and with age, about increased difficulty in managing treatment:

“The distance [to clinic], crowded clinics and waiting time for an operation had all added to my growing anxiety as I became more aware of the deterioration of my vision” (R214)

“I can imagine I will have real problems [with treatment] as I become less dexterous with age” (R141)

Questions about driving and the visual field test (VFT) required by the DVLA following a declaration of glaucoma in both eyes, prompted perhaps the most notable emotional responses. Not only was there manifest anxiety about the VFT with use of words like “daunting”, “nerve wracking”, “a lot at stake”, but also some degree of suspicion about the process:

“I had a really bad phone call to DVLA [they] kept calling me a liar … [it was] inhumane treatment” (R8)

“I didn’t find it helpful [I was] told the test is designed to catch you out. [I was] already very nervous” (R21)

“I went away feeling more anxious and worried than ever… the whole experience was ghastly” (R68)

This anxiety is perhaps understandable given the potential impact of failing a DVLA assessment, “This was devastation!! Not only had a loss of independence but my lifetime’s career also ended!” (R129).

Theme 2—lack of information

Participants not only expressed concerns about the amount of information that healthcare professionals provide (not enough), but that information is often more ‘clinical’ than’personal’.

“[there was] sufficient information … [but] it all feels formulaic and scripted” (R180)

“’you’ve got glaucoma’ here’s a prescription - no real explanation of condition or future treatment or prognosis” (R112)

“When diagnosed the emphasis was on treatment options with no info provided on disease itself” (R71)

Some responses indicated an uncertainty about how glaucoma might impact upon their sight and upon their lifestyle:

“Can someone define what impact any loss of visual field has on eyesight? No one has explained to me what I am not supposed to see” (R92)

“It is normally explained but I’m sorry to say that I do not understand what a good level of ‘17’ means. I receive the IGA magazine to try to understand more?” (R200)

A lack of information can lead individuals to feel that they lack understanding of their condition, and can also leave them feeling marginalised in the clinical relationship: “the hospital is so busy there does not seem to be a culture of explaining anything you are just moved in and out of the room by the nurse” (R157); “The staff at the hospital are under huge time pressure so there is little time to think of all questions when they give you bad news & no chance to contact them again with any queries you think of half an hour later” (R180).

“Google is fine for volume but hard to avoid extreme horrors” (R180); it is in this context that the IGA is recognised as important in addressing individuals’ information needs.

“Their leaflets provided me with the first and only information I have received …

“When my optician referred me, he didn’t explain anything, when I saw the hospital consultant, he gave little information. Only when my daughter rang IGA helpline did I receive any advice.” (R9)

“All aspects of the [IGA] are important and very helpful to me - especially leaflet and posters, magazine, and even more, support groups. Thank you. I feel I know and understand much more about this condition than any of my other medical (and ageing) problems. This is very reassuring” (R193)

Theme 3—asking questions

Concerns about a lack of information were mirrored by difficulties that respondents described in seeking information from healthcare professionals. Comment from R157 and R180 (above) suggest that individuals do not always find the clinical setting conducive to engaging with clinicians. Others repeated these sentiments more strongly, describing doctors who did not want to engage with them: “a very unpleasant consultant … refused to answer my questions” (R122); “only some doctors answer your questions” (R156); “consultants seem quite cagey with info” (R141); “[Consultant] was cold, prickly and obdurate, refusing to take any notice of what I said” (R35).

For others, the difficulty lies in not knowing how to ask questions about their glaucoma. This might be connected to a lack of knowledge making it hard for them to shape or construct meaningful questions; “I knew little about it until recently so just did as I was told” (R96). For others difficulties of memory or hearing inhibited them in asking questions, “being elderly I don’t always understand speech” (R34).

Preparing questions in anticipation of a clinic appointment was described by some as an effective strategy:

“clinics so busy would be nice to write a list of questions to have answered at appointments” (R31)

“went back to my next appointment with a whole a4 sheet of questions. My consultant answered them all and was very helpful.” (R67)

Others pointed to the importance of being confident enough to ask questions. Peer support might be an important part of this process:

“following support group meeting felt able to ask more questions” (R193)

“Sharing with fellow sufferers; valuable moral support, chance to ask questions of the experts” (R214)

Theme 4—positive patient involvement

Comments about peer support point to the value of individuals being actively engaged in their glaucoma management. Respondents suggested numerous ways in which this might take place.

At the simplest level seeking information on the internet was mentioned repeatedly. Others described participating in glaucoma support groups. Most often these were described as providing information and mutual support:

“since [they] started a group I have attended. It is very informative and offers me chance to find out the detail of glaucoma - not enough time in clinics for this and not at the same level in leaflets” (R50)

“I enjoy attending the informative meetings held when possible. It is good to meet other people and listen how their life has changed as well as being informed about the latest research in the area of glaucoma and its impact on people” (R165)

In a few cases information gathered in this way was described as directly informing treatment: “My consultant later confirmed it would be bad to take [the drugs] together in my case and wrote to the GP. Others may have believed their GP! Value of internet and support group in spreading knowledge” (R50); “[more than one visual field test] On request from me- not offered!” (R151).

More mundane examples of patients driving their own care by pursuing appointments and asking about treatment options were common: “[I] have had a history of having to fight for appointments and delays also” (R105); “while waiting for appointment I had to chase as I had been forgotten about and not on the list while waiting for laser treatment” (R160).

Theme 5—negative experiences

Approximately one-third of all coded data (i.e. those free-text responses which were considered to make a substantive comment) suggest a difficulty with glaucoma care, diagnosis or treatment, or a negative opinion about those involved in delivering services.

Comments from R105 and R160 (above) point to delays and waiting lists; this was the most common complaint amongst respondents with around one in ten commenting about delayed, postponed or forgotten appointments:

“I had not heard from the hospital for about 2 years approx. so I rang up and was given an appointment … I was told I have to wait 6 weeks [November] … after 6 weeks I rang up the hospital and was put onto the nurse who arranges the appointments. She told me I would have to wait until after Christmas. I am still waiting to hear …. In the meantime my eyesight is getting worse.” (R52)

Concerns about clinical pathways and treatment were less common, but still manifest in the responses offered:

“referral to specialist was late by non-specialist glaucoma ophthalmologist so caused more damage in my opinion” (R51)

“Nurses vague, do not seem properly trained for this role.” (R55)

“Each time I changed hospitals, from XX to YY and from YY to ZZ, all my hospital notes were lost” (R172)

“Feel that NHS glaucoma clinics are a bit of a conveyor belt. Consultants do not appear to have either the time or the inclination to explain their actions/changes” (R206)

Such difficulties led some respondents to challenge the competence of those delivering services, especially the DVLA VFT:

“A senior person sorted it out but only after 2 tests had gone wrong, by which time I was very stressed” (R84)

“was not put at ease. She lacked training and experience. Confused by her instruction and told ‘we’ll do one with glasses one without’ and as a result I paid for test at another branch” (R92)

“no privacy no explanation operator did not seem to know what to do. Complained but no apology” (R213)

Thematic synthesis

The preliminary stage of this thematic analysis—simple ‘word counts’ and assessment of ‘words in context’—suggests that some responses were more strongly associated with specific respondent groups, for example concerns about driving amongst those that drive; these patterns are displayed as ‘people’ in the thematic map.

Other patterns are worth noting and might warrant further consideration: respondents who engaged with private healthcare demonstrated more confident knowledge about glaucoma, whilst also demonstrating more concerns than those managed in the NHS; older respondents described more negative experiences, younger respondents more positive engagement with care; previous surgery was correlated to concerns about driving, more positive involvement in care was associated with those that have not had surgery.

This synthesis situates ‘information’ at the heart of an interconnected set of themes which typify the responses offered by IGA members Fig. 1. A lack of information can be a source of anxiety and uncertainty: not understanding clinical systems, being unable to formulate pertinent questions and feeling undervalued in clinical consultations. In contrast, the presence of information can enable engagement in self-care and can support changes in lifestyle which result in a more effective management of glaucoma. Understanding and meeting the information needs of individuals with glaucoma would seem an important priority for clinical services as well as for organisations like the IGA, which is explicitly recognised as an important source of information and support.

Drivers are an important sub-group who may require additional support in both the delivery and outcome of the DVLA driving assessment: in this analysis drivers displayed greater concern about diagnosis and more emotive responses.

Older people might benefit more from ‘safe spaces’ to raise questions about their glaucoma, the time pressure of a clinic may mean that additional resources/settings/provision are necessary to support this population with their understanding and management of glaucoma.

When clinics are cancelled it can result in stress and dissatisfaction with NHS services; specific information about when follow-ups will take place, and when patients should chase should be provided to maintain a patients’ engagement in their care and to increase patient satisfaction.

The results of this thematic analysis echoed the subjective experience of the IGA’s front-line staff, and we were keen to start to look at other qualitative data held by IGA services to see whether it could add to our understanding of the needs of people living with glaucoma.

IGA helpline call analysis

Sightline is the IGA’s telephone helpline. It operates during office hours and is staffed by two full-time advisors.

Call records are coded by the primary reason for each call, and for some years the most common primary reason has been surgery/laser, followed by eye drops, driving, ‘lifestyle’ topics, and clinic appointments. However, most helpline calls cover more than one topic, and as well as the primary call reason coding, detailed call data is recorded in free-text format in the charity’s database. We wanted to see whether the combination of topics covered in the calls could add to our understanding of patient needs. The helpline is open to anyone, and in the year to July 2019 only 32% of callers were current IGA members, giving us information from perhaps a wider demographic than the previous member-only thematic analysis.

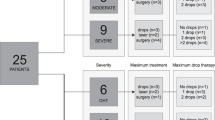

A review undertaken in June 2019 Tables 1 and 2. looked at Sightline calls received between July 2018 and May 2019; incomplete data was discounted, and the remaining 1002 call records from 708 individual callers were analysed by all topics covered in each call.

Call complexity

The mean number of topics covered in any one call was 2.2, and the maximum was 7. Some topics naturally engender more related topics, for example the category of “post-op problems” indicates surgery and more complex needs. The notable exception was driving, which were frequently single-issue calls Fig. 2.

Creating a conversation

Three quarters of callers rang only once in the 11-month period, and the maximum number of calls from any one individual was 11. The IGA encourages callers to keep in touch, and some enjoy updating Sightline advisors. The charity learns from these experiences, but we also recognise the benefit to the individual, keeping them engaged in their own condition and ensuring they always have access to relevant and useful information.

Caller anonymity

Of the 1002 calls analysed, 69 were made by anonymous callers. Sightline advisors report that anonymous callers do occasionally repeat-call but tend not to share their details: when anonymous, they prefer to remain anonymous.

The most common anonymous calls concerned driving and the DVLA (12), eye drops (12), lifestyle/diet (9), treatment concerns (6) and use of other medication (5).

The majority of anonymous driving/DVLA enquiries were broadly ‘regulatory’, for example the level of disclosure required, penalties for non-disclosure, and concerns about VFTs—often in advance of upcoming tests.

“Told by his ophthalmologist to let the DVLA know that he has glaucoma in both eyes. Called to ask if he really needed to…”

“Licence revoked and wanted to know what to do…”.

The type of driving query did not vary noticeably between anonymous and identifiable callers, but interestingly, those callers reporting—sometimes fairly significant—problems with either the DVLA or the VFT provider were all happy to share their personal details.

Among other anonymous calls, surprisingly few related to what might be considered ‘sensitive’ topics. There were four finance-related queries (access to free spectacles, prescription charges for eye drops, benefits of registration as sight impaired and fears for loss of livelihood and mortgage payments following diagnosis), two linked to mental health (interaction between drops and antidepressants), one query about the use of natural remedies and one caller wanted to change consultant, all of which could potentially be difficult to ask a clinician in a face-to-face meeting. The remainder of the anonymous calls were broadly representative of the attributed calls.

Overall, 22% of non-driving-related anonymous calls were from family members, who possibly felt their own contact details were irrelevant.

Only two anonymous callers were clearly in an emotional state at the time of the call. Keeping control of personal details may have been important in helping regain a feeling of control in their condition, or maybe they did not want to feel judged by the advisor.

Sightline allows people to talk about their condition frankly, ask “silly” questions and not be judged. The fact that the majority of callers are happy to provide their details indicates a high level of trust in the charity.

Surgery

It is perhaps no surprise that surgery is the most common topic covered in calls to the IGA. It is the most invasive aspect of glaucoma care and the majority of patients facing glaucoma surgery will have more advanced glaucoma which has not responded to eye drops. These patients are likely to be facing a choice between surgery or some degree of sight loss. Surgical calls are often complex and lengthy Table 1, and commonly combine with queries about cataracts, eye drops, post-op problems, treatment concerns, and other eye conditions (Table 2).

Calls about the interaction between glaucoma and cataract surgery were far more common than we had realised prior to this analysis, occurring in c 20% of surgery calls. Callers highlighted a lack of available information on this topic, and a new patient information booklet is planned.

With eye clinics stretched to capacity or beyond, it can obviously be difficult for clinicians to give patients the time and space they need to understand their condition and treatment options. Talking to a Sightline advisor allows a patient to think aloud and start to frame the questions they need answering in order to manage their care.

“Has exfoliative glaucoma and has had cataract extraction performed in one eye. She was told that the lens now needs ‘polishing’. I explained the only thing I think this could be is a PCO and that once a laser capsulotomy has been formed then her vision in that eye should return to how it was following her cataract op. She also has a cataract in the other eye and her consultant has said to leave it as long as possible. Again she does not understand why. She says the consultant doesn’t really explain things very well. She may opt to see another consultant privately. I have suggested that she takes someone along with her.”

“Has had pigmentary glaucoma for 30 years and is registered with severe sight loss. His C/D ratios measure 0.9 …. C/D measurements and their meaning were explained in detail.”

It was common for callers to want help to decide between treatment options, or to have a decision validated or indeed made for them by Sightline. This is obviously outside the remit of a helpline, but Sightline fills an information void, which mean patients are reassured and empowered to go ahead with treatment. Where a patient declines surgery having spoken to Sightline, they are in a better position to understand the risk they are taking and the potential impact.

“We discussed the implications of not having surgery and how no guarantees can be given but that the trab is a very good operation. I have suggested at his next visit he asks to see a copy of his VF test on his left eye before and after the trab as he is unsure whether he lost vision or not with that eye.”

“Has [had] an aggressive form of glaucoma for the past 5 years; has had 3 trabs in her left eye and has very little vision left now …. should have had the trab in her right eye in early March but told [her consultant] that she needed to think about it for a while longer. He wasn’t happy but understood. After speaking to me she has decided to go ahead with it.”

“She asked should she have consented to having eye drops to the eye that hasn’t got glaucoma as a preventative and I expressed my opinion that it was probably a very good idea. She is also very keen to have the trab now so that hopefully she won’t have to have eye drops which she doesn’t tolerate well.”

Call data often demonstrates a real willingness on the part of patients for positive involvement in their own care, but this is frequently coupled with a lack of confidence and/or difficulty framing appropriate questions:

“He had a trab two years ago and is experiencing blurred vision and diplopia … has lost a lot of peripheral vision. He also has a cataract forming. Seeing consultant in a week’s time and wanted some ideas of the sort of questions he should be asking”

“Seeing con. on Friday, has written questions to give to him and wanted to run them past me to see if they were OK. She is also bringing a friend along to write down his answers.”

“Wanted to know if it was his right to request to see his consultant. He feels his eyes are getting worse and as he sees someone different each time he feels the treatment is not as good as it could be. …. He said he has spoken to the secretary but she wasn’t very helpful and wouldn’t listen to him”

Anxiety associated with glaucoma was apparent in many surgery and laser calls. In a number of calls this was exacerbated by lack of consistency in treatment, engendering a lack of trust and confidence in clinicians:

“… At the hospital she attends many of the ophthalmologists have left ……. She is apprehensive because her laser treatment is likely to be performed by a locum. She is still unsure exactly what laser treatment she is having and is going to contact the hospital to find out. I have suggested that it will probably be SLT. We discussed what this would consist of any how they hope it to work.”

“Has NTG. Had trab in right eye Feb 2018. Has PCO in the right eye and awaiting capsulotomy since March. Have advised him to call appointments team re date and ask about present waiting time. IOP’s last month measured 12 mmHg. Also has dry eyes and doesn’t always use the gel and the pain can then return. Suggested he uses them consistently and if this doesn’t relieve the pain then maybe there is a different cause. After our discussion though it does sound like dry eye disease. He is concerned that his consultant doesn’t explain things fully to him.”

“April 2018 consultant concerned with her glaucoma and whether drops were working. Op mentioned but she wanted to carry on using drops. That consultant left, 2nd consultant recommended laser but then left. 3rd consultant has recommended a Trab. She has now received a referral to XXX though she doesn’t know which consultant referred her.”

The route to making a decision is complex, and many patients need considerable support, advice and time:

“She has narrow angles, discovered during an eye health check. She has been advised to have bilateral iridotomies. She was tearful and stated that she is going blind. Condition discussed at length and how the laser treatment is a preventative. Reassured.”

Buddies

The heat map shows a hot spot where calls cover both surgery queries and discussion of IGA Buddies. A buddy is a volunteer who has been through a surgical or laser procedure and who provides telephone support to others facing the same treatment. Unlike other call topics, Buddy discussions were primarily initiated by Sightline staff rather than callers (members’ knowledge of the Buddy scheme is lowFootnote 1 and likely to be even lower in non-members). As expected, call data showed strong evidence of the role peer support can play in positive patient involvement as outlined in the thematic synthesis:

“Spoke to her buddy and found it very useful and reassuring. She has since had a lovely holiday away and is due to have her trab on XX/2018 under general anaesthetic.”

“She found speaking to her buddy very helpful. She has gone from being unsure about having the shunt surgery to having it done. It has helped with her anxieties and she is going to call her buddy following her operation.”

“Had a very good 45 mins discussion with his buddy which he found most helpful …. After his op he will get in touch with us to put himself forward as a buddy.”

Eye drops

Eye drops are the second commonest reason for calling and queries are often coupled with other questions, most commonly appointments, laser, dry eye, compliance aids, and treatment concerns.

The call data clearly illustrates that patients’ management of drops is vulnerable: adherence issues were common, and we cannot assume a patient who appears to be managing their drops well will continue to do so if their drop regime changes for any reason. The problem of a lack of patient education and understanding of their condition persists, and more care should be taken to ensure people receive accurate and thorough information at the point that drops are prescribed:

“Was told she had glaucoma and was prescribed Latanoprost but decided not to take anything at that time due to having a holiday booked. Couldn’t understand why she would need them as her IOP is 17 in each eye and she knows that means she is within the range of 10–24 mmHg.”

“… always puts Ganfort in at night and her IOP/glaucoma is well maintained and controlled. At her last appointment she was told to start putting it in am rather than pm. She hasn’t changed as everything is fine.”

“54-year-old gentleman who had bilateral laser iridotomies twenty years ago and prescribed eye drops which he didn’t continue with. He has peripheral loss of vision and glaucoma was diagnosed two weeks ago (picked up from having treatment for a CRVO). He is now on Xalatan and naturally concerned about going blind. We discussed this and the importance of not forgetting to put his drops in, punctal occlusion and glaucoma treatments available.”

“Had NTG since 2011. On three different drops and has had laser treatment x2. She has been prescribed Amitriptyline for peripheral neuropathy and is on Lansoprazole and antihistamines which are all contraindicated for glaucoma. I explained that usually this is referring to people with acute angle closure glaucoma which she doesn’t have. I have asked her to check with her consultant. ….”

Many calls illustrated that patients do really want to get drop management right and that fear of getting it wrong leads to anxiety. Timely information provision is absolutely key, and there is much evidence to suggest this is still not being provided: when helping new patients with their drops, we recommend asking them who could help if required, and where they can go for help.

“He doesn’t have anyone around to confirm whether or not the drop is going in. He keeps them in the fridge but is still unsure.… I advised him to take his eye bottle to his GP surgery and ask a nurse to watch him to see if he is doing it correctly.”

“Is on Ganfort and Clinitas for dry eyes. Leaves an hour between the two drops and asking if he is doing the right thing. Reassured him that he is.”

“On Trusopt and Lumigan and asking if he can miss one of the drops each day as he is finding his vision very blurred. We discussed dry eyes and I have advised him to contact the secretary at the hospital to get his appt brought forward. I also advised not to leave a drop out and the reasons.”

As with surgery, a number of calls involved giving callers the confidence to address treatment concerns or navigate the interaction between different conditions and differing clinical advice:

“Has been taking drops for glaucoma since 2010. He has wet AMD in one eye and dry AMD in the other. He has been having injections for the wet AMD. Has been told to stop Latanoprost as this can affect the macular and will be seen in 3–4 months’ time. He has POAG and IOPs are usually 14 mmHg. He had a VFT one month ago which he was told needs looking into. He is naturally wary of stopping the drops and I have advised him to ring the secretary to find out the exact reason for stopping and what will happen to his glaucoma during this time. Is going to let me know how he gets on and the thinking behind this change in treatment.”

A number of calls about eye drops covered supply issues for specific drops although this was perhaps skewed by atypical supply chain issues during 2018 combined with a small number of calls relating to supply worries post Brexit.

Driving and the DVLA

Driving and the DVLA is the third most common call topic, and is much more likely than surgery or eye drops to be a single-issue call. Callers typically seek information on rules and regulations, for example clarification about whether the DVLA need to be notified if an individual has OHT in one eye and glaucoma in the other (A: only if they are a commercial Group 2 driver) or how to manage a previous failure to disclose (A: the DVLA will never punish a driver for withholding a declaration for a period of time; however, that driver is committing an offence, and they risk invalidating their insurance in the event of an incident).

It appears there remains confusion amongst professionals, both ophthalmologists and optometrists, regarding the regulations, and patients continue to receive incorrect or inconsistent advice. A particular bugbear for callers who—having informed the DVLA about a condition when they did not need to—is that having told the DVLA about their condition, they join the group of “drivers with a medical condition”. It can be hard to get this tag to be removed from drivers’ records, meaning individuals have to continue taking unnecessary visual fields tests.

Some callers need assistance and guidance following the revocation of a driving licence. Communication from the DVLA is improving, but drivers are not always told about their right to make an informal appeal; this lack of information often causes a good deal of stress, as callers think they have to launch directly into an all-or-nothing formal appeal which can also incur costs. Likewise a number of callers are not aware of their right to receive a copy of their VFT results and the IGA recommends that the DVLA provides this information more clearly to drivers.

Some callers need information about why a licence may have been revoked: as previously noted, many long-term patients do not have an understanding of their glaucoma and struggle to understand the impact of glaucoma sight loss, which can leave them feeling the decision was unjust. Showing patients an illustration of glaucoma sight loss can be helpful in aiding understanding. A lack of understanding of the basics of glaucoma is illustrated in the number of calls asking whether surgery or laser will improve vision and therefore ability to drive. Combination calls also include post cataract or laser recovery times and when it is safe to drive again.

As found in the thematic analysis, advisors report that callers with driving queries are often extremely upset and anxious. Advisors encourage callers to make an informal appeal if appropriate, and the news for these callers is surprisingly reassuring (Tables 3 and 4).

Appointments

Queries about appointments comprise 12% of helpline calls, but surprisingly, general queries account for two-thirds of these and concerns about delayed and cancelled appointments for only one-third.

“Has always been given transport to and from the hospital as too far to travel by public transport. Has been taken over by another company who now say he is not within the criteria of free transport but they would not explain why.”

General queries reveal a common lack of knowledge about how to move between hospitals or consultants, and it is clear that patients often do not realise the level of choice they have regarding their care. Improved information on how to navigate initial referral by an optometrist into hospital eye services would also benefit glaucoma suspects:

“Was referred by optometrist. Decided to go on NHS online to book an appointment. No appointments were available … Concerned about the delay and wanted to know what drop he could use as he would buy it online. I advised him not to do this as he needs to see a consultant who will advise on the treatment he needs.”

Many callers worry about how frequently various tests should be carried out and the ‘ideal’ frequency of appointments; new patients in particular want a ‘rule of thumb’ for appointment schedules. Providing a minimum and maximum recall time could significantly ease patients fears and may aid their understanding of their condition. Unexplained changes to booking and administration systems are also a source of stress and worry. Clearer advance communication from clinics explaining changes in clinic type (e.g. traditional to virtual) or location would provide reassurance.

When calls are about delayed appointments, callers are likely to exhibit anxiety or distress, and many also require support to empower them to address this. Common information needs include how to prepare for a first appointment or an appointment in a new location or setting: what will happen, what to take etc. This information could usefully be provided in every appointment letter.

Laser

The fifth most common call topic is laser treatment. Not surprisingly, the heat map shows calls about laser treatment commonly also involve discussion of narrow angles and PACG. Otherwise the themes and information needs of callers are very similar in kind to calls about surgery: what to expect from laser treatment, how it works, whether it is necessary, and how long the recovery period will be. As with surgery, it is not uncommon for callers to express fear and anxiety and a nervousness about accessing timely care:

“Very strong family history of glaucoma. Was diagnosed in his mid 40’s. Laser was done but this didn’t work so he has been on drops ever since. He is now on the maximum of eye drops and his consultant suggested SLT to him as they have the equipment on loan so very short notice. He called for more information and what to expect as he is having it done today.”

“Due to have a YAG laser but not sure what for. She explained that it is to remove a film in the eye. She had cataract extractions 20 years ago and I think that it is possibly a YAG laser capsulotomy that she will be having and not laser treatment for glaucoma as she thinks. I discussed this with her. She is going to look for the letter and call me back tomorrow.”

Discussion

The patients who have navigated a path to the IGA’s support services or who have joined the IGA as members are probably not typical glaucoma patients. The very acts of calling or joining indicate a desire for information about their glaucoma: they are—to a greater or lesser degree—actively engaged in their own care. Yet even they experience an information void, and their information needs are complex–equally complex for those newly diagnosed as those diagnosed decades ago.

So what does matter to patients? The disease itself engenders fear and anxiety: patients are terrified of going blind and losing their independence. Two of the three most common call topics relate to this: surgery and driving. Take the time to explain to patients the prognosis and risks of their condition and treatment, in a manner suitable to them. Trabeculectomies might be your bread and butter, but for that patient, the prospect of someone taking a knife to their eye is terrifying, and they are unlikely to forget how you delivered the news to them.

Patients sometimes need a surprising amount of information and crucially, time, to make informed decisions about their care. Even patients who initially appear relatively well-informed often lack some necessary information or skills to manage their condition. Offer them information about their condition and treatment (IGA patient information is free to order!) and encourage them to ask questions. Provide a means for them to get back in touch with the clinic, if required.

Patients’ ability to manage their condition varies depending on their personal circumstances. This is especially true for topics such as eye drops. Drops change, personal circumstances change, attitudes to treatment evolve. Continue checking in with your patients, encourage discussion and frame questions to avoid judgement or censure. Turn “You’re managing OK with your drops, yes?” into “Do you have any concerns or difficulties with your eye drops? I can help you with that”.

Glaucoma patients value the support and understanding of their peers. If you do not have a glaucoma patient support group in your clinic, the IGA can help you set one up.

Institutional communications add to patient fear and anxiety. You work for an institution that has agency over patients—be it medical, clinical or regulatory; but from a patient perspective that agency often feels ill-used or unfair. The information void is huge, yet noone in this analysis complained of having too much information. Communications about transport, appointments, recall schedules, changes to clinic type, and driving should be clear, honest and timely. Could you increase the amount of information included in standard clinic letters? It may go some way to easing patient’s fears and retaining trust.

This has been a useful exercise for the IGA and we are very grateful to EK and PL for their insights. We have been working for some time to hone and improve the way we categorise and record data on patient needs, and this exercise has helped refine that process. The heat mapping exercise revealed a lack of patient information on glaucoma and cataracts, and we can now fill that void. Future areas for study include tracking repeat caller topics, more detailed contextual call mapping, and analysis of information needs at different stages of a glaucoma journey. A new more automated data retrieval system will also enable us to use thematic mapping techniques and cross-referencing across all call data, and we are excited to see what this shows.

“For a glaucoma patient to be able to pick up the phone to discuss a worrying problem and have such a caring person there to help is so comforting … Today is the first day I have enjoyed myself and felt like my old self”.

Notes

In the 2017 IGA member survey only 44% of 854 responders were aware of the service, and there is significant anecdotal evidence to support this lack of awareness.

Funding

The IGA funded the University of Nottingham to undertake the thematic analysis at the start of this article, using charitable funds.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This is original material that has not been previously published and has not been submitted for publication elsewhere.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Osborn, K., Bradley, J., Knox, E. et al. What matters to patients? A thematic analysis of patient information and support needs. Eye 34, 103–115 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-019-0644-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-019-0644-3

This article is cited by

-

Driving and glaucoma in the UK: a national survey of clinicians’ advice and guidance to patients

Eye (2023)

-

What matters to you? Embracing shared decision making in ophthalmology

Eye (2021)

-

Effect of variations of corneal physiology on novel non-invasive intraocular pressure monitoring soft contact lens

Biomedical Microdevices (2021)