Abstract

Background/objectives

Fibrillin-1 (FBN1) mutations cause connective tissue dysgenesis the main ocular manifestation being ectopia lentis (EL), which may be syndromic or non-syndromic. We describe a pedigree with a FBN1 mutation causing non-syndromic EL with retinal detachment (RRD) and their management.

Subjects/methods

Patients with familial EL with RRD were invited to participate (vitreoretinopathy branch of Target 5000, the Irish inherited retinal degeneration study). All patients signed full informed consent. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Mater Hospital, Dublin and abided by the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Seven adults were affected with bilateral EL. All subjects had RRD with bilateral non-synchronous RRD in 57%.

Conclusions

The FBN1 variant described herein confers an increased risk of both EL and RRD and can now be upgraded to ‘pathogenic’ ACMG status.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Mutations in the fibrillin-1 gene (FBN1, chromosome 15q21.1, OMIM *134797) are associated with autosomal dominant disorders of connective tissue. Ectopia lentis (EL) is the primary ocular manifestation of the type-1 fibrillinopathies that include non-syndromic EL (NSEL) (OMIM #129600) and syndromic EL (SEL). The phenotypic manifestation of SEL versus NSEL and their severity depends on the position and extent of pathogenicity of the causative FBN1 mutation.

FBN1 is a large gene (>200 kb) comprising 66 exons, producing a five domain, 2871-amino acid extracellular protein [1]. Mutant fibrillin protein disrupts microfibril formation and function [2] degrading more rapidly than wild type [3,4,5]. TGF-β-mediated inflammatory elastolysis may play a role [6]. Proteomic studies indicate fibrillin-1 is the most abundant protein in ciliary zonules [7, 8]. Knockout of FBN1 in a murine model manifested zonular rupture [9].

The archetypal type-1 fibrillinopathy is Marfan Syndrome (MFS, OMIM #154700) whose diagnostic criteria include cardiac (aortic dissection), ocular (EL) and systemic signs (catalogued in the revised Ghent Criteria [10]). The major ophthalmic criterion is EL. However, other ocular features include axial myopia, corneal flattening, astigmatism, glaucoma and rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (RRD) [6, 11, 12]. Phenotype may be exclusively ocular (i.e. NSEL), or include a systemic syndrome (SEL), relevant for prognosis/management.

Methods

Patients with EL were recruited to Target 5000 [13,14,15]. All participants completed written informed consent. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the Mater Hospitals, Dublin, Ireland and abides by the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients underwent a detailed history and comprehensive ophthalmic examination. Affected relatives were included. Relevant historical ophthalmic details were included and retrospective non-randomised, non-masked analysis was performed. Multimodal retinal imaging was performed: colour and autofluorescence imaging (Optos plc, Scotland) and Optical Coherence Tomography (SD-OCT, Carl Zeiss Meditec, Germany).

Genotyping by direct sequencing was performed at The School of Genetics and Microbiology, Ocular Genetics Lab, Trinity College Dublin. The variant described herein was first observed in index cases by the Wessex Regional Genetic Laboratory.

The surrounding genomic region was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR, primers: forward: 5′-CCCTGTTGGTTTGTTGCTCT-3′; reverse: 5′-TGAGAATGCCATTTGAGCTTTTG-3′). Templates were amplified using Q5 High Fidelity Polymerase (New England Biolabs). PCR products were purified using the GeneJET Gel Extraction Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Sanger sequencing was conducted by Eurofins Genomics (Ebersberg, Germany).

Results

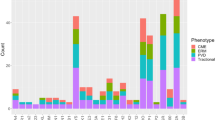

Seven affected (mean 58.43 ± 15.02 years) and two unaffected (mean 56.50 ± 0.71 years) adults from two generations of a single NSEL pedigree were recruited (Fig. 1). Those included had bilateral EL, high axial myopia (axial length (AL) 26.66 ± 1.29 mm, n = 10/14) and RRD/intraoperative breaks) without other trauma.

Pedigree diagram of non-syndromic ectopia lentis showing autosomal dominant inheritance. All investigated individuals are annotated with their observed genotype concerning the variant FBN1 NM_000138:c.1916G>A, p.Cys639Tyr. A ‘plus’ indicates an agreement with the reference base whereas a ‘minus’ indicates the presence of the variant of interest. Squares, circles and diamonds represent males, females and people of unknown gender, respectively. Individuals affected by ectopia lentis are indicated by a red marker

RRD was diagnosed in all seven affected patients (11/14 eyes, 78%) and zero eyes of unaffected relatives. Bilateral non-synchronous RRD occurred in 4/7 affected subjects (57%). Re-detachment occurred in 1/11 (9%). RRD occurred intra-/post-operative in 64%, the remainder being surgically naïve eyes. The RRD rate in this pedigree is significantly higher than the reported rate of EL-related RRD, (0–25%) [6, 11, 16,17,18,19,20].

There was no personal/family history of aortic root/valve defects confirmed by normal serial echocardiography. Thus, no member of this pedigree meets the revised Ghent criteria for the diagnosis of MFS [10].

Molecular genetic testing detected a previously reported [21] mutation in FBN1 [1] (NM_000138:c.1916G>A, p.Cys639Tyr) although detailed phenotyping was not available in the prior study. In the current study, the Cys639Tyr mutation was confirmed in all affected adults and neither unaffected relative.

Discussion

Genetics

Structurally relevant FBN1 variants are seen in SEL including MFS [22], but also in NSEL [21, 23]. FBN1 mutations are the primary cause of inherited EL (SEL and NSEL), although other genes have been implicated in recessive EL (e.g. ADAMTSL4, ADAMTS10) [21, 24]. Most EL pedigrees have private FBN1 mutations [25] (>1500 variants reported [26,27,28]). This same rare FBN1 variant manifesting in two disparate ethnic groups suggests sensitivity to mutagenesis at this position, a postulation supported by four different pathogenic missense variants reported in p.Cys639 [29].

This missense variant replaces a cysteine residue with tyrosine in one of the fibrillin-1 protein’s EGF-like domains. Fibrillin-1 cysteine loss is associated with zonular instability/EL [19, 30, 31]. It is plausible that this pedigree lacks any additional pathogenic cardiac risk variants although comprehensive testing of these genes (e.g. SMAD3, COL4A1, ECE1) was not performed. The c.1916G>A variant has been previously reported in segregation with NSEL [21]; however, detailed phenotyping was lacking and ACMG grading only satisfied the ‘likely pathogenic’ variant status criteria. Detailed phenotyping and lines of mutation evidence from this pedigree allows promotion of this FBN1 variant to ‘pathogenic’ ACMG status.

Systemic

The fatal manifestation of MFS is aortic dissection, typically occurring before 40 years [32] (mean age of affected individuals here being 58.43 ± 15.02 years). Aortic root disease in type-1 fibrillinopathies may be progressive, thus NSEL should not be diagnosed before 20 years of age and serial echocardiography is recommended for life [10, 23].

We have referred to this pedigree’s phenotype as ‘NSEL’ to dissociate both from MFS stigma (i.e. insurance, mortality [10]) and to accentuate the other blinding ocular features that ‘isolated EL’ does not adequately highlight (i.e. RRD, glaucoma). Presentation with poor vision often occurs early in both MFS and NSEL [21] allowing detection of both familial and sporadic cases, facilitating instigation of systemic investigations and treatment.

Axial myopia may be (1) a genetic feature of this FBN1 variant, (2) related to other myopia risk genes or (3) acquired as a result of lens blur-induced myopia from the ectopic lens [33]. Longer AL is associated with both higher prevalence of EL and RRD in type-1 fibrillinopathies [34].

RRD was diagnosed in all affected patients, with 57% bilateral, non-synchronous RRD. In this cohort intraoperative retinal tears were documented in 14% (n = 2/14), a feature not reported in previous EL publications. Thirty-six percent of RRD (n = 4/11) occurred in surgically naïve eyes with no precipitating trauma. Individual surgeon factors can be excluded from the remainder as surgery was performed by three separate vitreoretinal surgeons. In large cohorts of SEL (mainly MFS), RRD is a prominent feature both pre- and post- vitreolensectomy surgery [11], the published post-operative RRD rate ranging from 0 to 25% [3, 6, 10, 11, 16,17,18,19,20,21, 27, 28]. Thus, this FBN1 variant may confer an increased risk of RRD (100% of individuals, 79% of eyes) and intraoperative retinal breaks. There is a lack of data in the literature on the retinal phenotype of NSEL. This may be due to an automatic labelling of any case of EL as ‘MFS.’ Prophylactic 360-degree retinopexy akin to the Stickler Syndrome Cambridge protocol [35] may be performed.

The current study investigates the phenotype of a single pedigree and a single FBN1 variant whereas, other studies describe various unrelated EL probands with distinct FBN1 variants. This may partly explain the high incidence of RRD in this cohort. Regular surveillance for RRD must be performed for all people with a known pathogenic FBN1 mutation or an EL phenotype whether syndromic or not.

Conclusion

The genetic findings from this pedigree add significantly to the existing data, upgrading the ACMG grading of this FBN1 variant to pathogenic. The ability to perform targeted sequence-based testing for this specific FBN1 variant in future generations will allow informed decisions to be made regarding necessity and timing of intervention/prophylaxis [36] for EL and RRD.

Summary

This paper describes a pedigree with a pathogenic FBN1 variant manifesting as non-syndromic ectopia lentis with prevalent retinal detachment. Systemic features (specifically cardiac) were absent in all cases.

What was known before

-

Ectopia lentis is a feature of Marfan Syndrome, difficult refractive management choices, especially in children.

-

Retinal detachment is a common feature (up to 25% of cases).

What this study adds

-

A specific missense variant with 100% of affected individuals with detachment, 57% bilateral. Genetic diagnosis, monitoring critical ± prophylaxis.

References

Biery NJ, Eldadah ZA, Moore CS, Stetten G, Spencer F, Dietz HC. Revised genomic organization of FBN1 and significance for regulated gene expression. Genomics. 1999;56:70–7.

Jensen SA, Handford PA. New insights into the structure, assembly and biological roles of 10–12 nm connective tissue microfibrils from fibrillin-1 studies. Biochem J. 2016;473:827–38.

Aoyama T, Francke U, Dietz HC, Furthmayr H. Quantitative differences in biosynthesis and extracellular deposition of fibrillin in cultured fibroblasts distinguish five groups of Marfan syndrome patients and suggest distinct pathogenetic mechanisms. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:130–7.

Reinhardt DP, Ono RN, Notbohm H, Muller PK, Bachinger HP, Sakai LY. Mutations in calcium-binding epidermal growth factor modules render fibrillin-1 susceptible to proteolysis. A potential disease-causing mechanism in Marfan syndrome. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:12339–45.

Hubmacher D, Apte SS. Genetic and functional linkage between ADAMTS superfamily proteins and fibrillin-1: a novel mechanism influencing microfibril assembly and function. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:3137–48.

Nemet AY, Assia EI, Apple DJ, Barequet IS. Current concepts of ocular manifestations in Marfan syndrome. Surv Ophthalmol. 2006;51:561–75.

De Maria A, Wilmarth PA, David LL, Bassnett S. Proteomic analysis of the Bovine and Human Ciliary Zonule. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017;58:573–85.

Eckersley A, Mellody KT, Pilkington S, Griffiths CEM, Watson REB, O'Cualain R, et al. Structural and compositional diversity of fibrillin microfibrils in human tissues. J Biol Chem. 2018;293:5117–33.

Jones W, Rodriguez J, Bassnett S. Targeted deletion of fibrillin-1 in the mouse eye results in ectopia lentis and other ocular phenotypes associated with Marfan syndrome. Dis Model Mech. 2019;12:dmm037283.

Loeys BL, Dietz HC, Braverman AC, Callewaert BL, De Backer J, Devereux RB, et al. The revised Ghent nosology for the Marfan syndrome. J Med Genet. 2010;47:476–85.

Chandra A, Ekwalla V, Child A, Charteris D. Prevalence of ectopia lentis and retinal detachment in Marfan syndrome. Acta Ophthalmol. 2014;92:e82–3.

Izquierdo NJ, Traboulsi EI, Enger C, Maumenee IH. Glaucoma in the Marfan syndrome. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1992;90:111p–7p. discussion118-22

Dockery A, Stephenson K, Keegan D, Wynne N, Silvestri G, Humphries P, et al. Target 5000: target capture sequencing for inherited retinal degenerations. Genes (Basel). 2017;8:E304.

Carrigan M, Duignan E, Malone CP, Stephenson K, Saad T, McDermott C, et al. Panel-based population next-generation sequencing for inherited retinal degenerations. Sci Rep. 2016;6:33248.

Farrar GJ, Carrigan M, Dockery A, Millington-Ward S, Palfi A, Chadderton N, et al. Toward an elucidation of the molecular genetics of inherited retinal degenerations. Hum Mol Genet. 2017;26(R1):R2–11.

Rabie HM, Malekifar P, Javadi MA, Roshandel D, Esfandiari H. Visual outcomes after lensectomy and iris claw artisan intraocular lens implantation in patients with Marfan syndrome. Int Ophthalmol. 2017;37:1025–30.

Maumenee IH. The eye in the Marfan syndrome. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1982;18:515–24.

Konradsen TR, Zetterstrom C. A descriptive study of ocular characteristics in Marfan syndrome. Acta Ophthalmol. 2013;91:751–5.

Schrijver I, Liu W, Brenn T, Furthmayr H, Francke U. Cysteine substitutions in epidermal growth factor-like domains of fibrillin-1: distinct effects on biochemical and clinical phenotypes. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65:1007–20.

Manning S, Lanigan B, O’Keefe M. Outcomes after lensectomy for children with Marfan syndrome. J aapos. 2016;20:247–51.

Li J, Jia X, Li S, Fang S, Guo X. Mutation survey of candidate genes in 40 Chinese patients with congenital ectopia lentis. Mol Vis. 2014;20:1017–24.

Arbustini E, Grasso M, Ansaldi S, Malattia C, Pilotto A, Porcu E, et al. Identification of sixty-two novel and twelve known FBN1 mutations in eighty-one unrelated probands with Marfan syndrome and other fibrillinopathies. Hum Mutat. 2005;26:494.

Zadeh N, Bernstein JA, Niemi AK, Dugan S, Kwan A, Liang D, et al. Ectopia lentis as the presenting and primary feature in Marfan syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155a:2661–8.

Chandra A, Aragon-Martin JA, Hughes K, Gati S, Reddy MA, Deshpande C, et al. A genotype-phenotype comparison of ADAMTSL4 and FBN1 in isolated ectopia lentis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:4889–96.

Dietz HC, Cutting GR, Pyeritz RE, Maslen CL, Sakai LY, Corson GM, et al. Marfan syndrome caused by a recurrent de novo missense mutation in the fibrillin gene. Nature. 1991;352:337–9.

Faivre L, Collod-Beroud G, Loeys BL, Child A, Binquet C, Gautier E, et al. Effect of mutation type and location on clinical outcome in 1,013 probands with Marfan syndrome or related phenotypes and FBN1 mutations: an international study. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:454–66.

Stenson PD, Mort M, Ball EV, Shaw K, Phillips A, Cooper DN. The human gene mutation database: building a comprehensive mutation repository for clinical and molecular genetics, diagnostic testing and personalized genomic medicine. Hum Genet. 2014;133:1–9.

Collod-Beroud G, Le Bourdelles S, Ades L, Ala-Kokko L, Booms P, Boxer M, et al. Update of the UMD-FBN1 mutation database and creation of an FBN1 polymorphism database. Hum Mutat. 2003;22:199–208.

Landrum MJ, Lee JM, Benson M, Brown GR, Chao C, Chitipiralla S, et al. ClinVar: improving access to variant interpretations and supporting evidence. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(D1):D1062–7.

Zhao JH, Jin TB, Liu QB, Chen C, Hu HT. Ophthalmic findings in a family with early-onset isolated ectopia lentis and the p.Arg62Cys mutation of the fibrillin-1 gene (FBN1). Ophthalmic Genet. 2013;34:21–6.

Yang G, Chu M, Zhai X, Zhao J. A novel FBN1 mutation in a Chinese family with isolated ectopia lentis. Mol Vis. 2012;18:945–50.

Attias D, Stheneur C, Roy C, Collod-Beroud G, Detaint D, Faivre L, et al. Comparison of clinical presentations and outcomes between patients with TGFBR2 and FBN1 mutations in Marfan syndrome and related disorders. Circulation. 2009;120:2541–9.

Fujikado T, Kawasaki Y, Suzuki A, Ohmi G, Tano Y. Retinal function with lens-induced myopia compared with form-deprivation myopia in chicks. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1997;235:320–4.

Patricia CW, Hoskins HD, The developmental glaucomas. In: Tasman W, editors. Duane’s clinical ophthalmology. 2005.

Fincham GS, Pasea L, Carroll C, McNinch AM, Poulson AV, Richards AJ, et al. Prevention of retinal detachment in Stickler syndrome: the Cambridge prophylactic cryotherapy protocol. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:1588–97.

Abboud EB. Retinal detachment surgery in Marfan’s syndrome. Retina. 1998;18:405–9.

Acknowledgements

Fighting Blindness Ireland. Clinical Research Centre, Mater Misericordiae University Hospital, Dublin, Ireland. Retina Centre & Eye Laser, Mater Private Hospital, Dublin, Ireland. School of Genetics and Microbiology, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland. Our Lady’s Children’s Hospital, Crumlin, Dublin, Ireland. Wessex Regional Genetics Laboratory, Salisbury, UK.

Funding

Health Research Board Ireland. Science Foundation Ireland. Fighting Blindness Ireland. Medical Research Charities Group Ireland.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Stephenson, K.A.J., Dockery, A., O’Keefe, M. et al. A FBN1 variant manifesting as non-syndromic ectopia lentis with retinal detachment: clinical and genetic characteristics. Eye 34, 690–694 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-019-0580-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-019-0580-2