Abstract

Place plays a significant role in our health. As genetic/genomic services evolve and are increasingly seen as mainstream, especially within the field of rare disease, it is important to ensure that where one lives does not impede access to genetic/genomic services. Our aim was to identify barriers and enablers of geographical equity in accessing clinical genomic or genetic services. We undertook a systematic review searching for articles relating to geographical access to genetic/genomic services for rare disease. Searching the databases Medline, EMBASE and PubMed returned 1803 papers. Screening led to the inclusion of 20 articles for data extraction. Using inductive thematic analysis, we identified four themes (i) Current service model design, (ii) Logistical issues facing clinicians and communities, (iii) Workforce capacity and capability and iv) Rural culture and consumer beliefs. Several themes were common to both rural and urban communities. However, many themes were exacerbated for rural populations due to a lack of clinician access to/relationships with genetic specialist staff, the need to provide more generalist services and a lack of genetic/genomic knowledge and skill. Additional barriers included long standing systemic service designs that are not fit for purpose due to historically ad hoc approaches to delivery of care. There were calls for needs assessments to clarify community needs. Enablers of geographically equitable care included the uptake of new innovative models of care and a call to raise both community and clinician knowledge and awareness to demystify the clinical offer from genetics/genomics services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Where we live influences our health and access to health care services plays a key role.(1) Accessing care can be attributed to both ‘composition’ factors (i.e., the characteristics of people who live in particular localities e.g. age and socioeconomic status) and ‘context’ factors (i.e. the influence of the wider environment in which people live e.g. the quality of the built environment and availability of services) [1]. In particular, limited availability of services has been reported to present specific challenges and so, affect health care utilisation [2,3,4]. Here we focus on ‘context’ and geographically equitable access to services. Health geography literature to date has identified the presence of inequalities in accessing health care due to place across multiple specialities such as, emergency care [5] and drug use [6] with barriers reported, such as, spatial disequilibrium of services and difficulties in travelling to services [5,6,7,8,9]. Some factors influencing equitable access to genetic/genomic services have previously been examined e.g. underserved communities [10] and navigating the health system [11]. However, the influence of geography on equity of access to genetic/genomic services is less clear.

Traditionally genetic, and in particular, genomic health care services have been centred around specialist tertiary hospitals. With the need for highly specialised teams interacting across the laboratory and clinics with rapidly evolving knowledge and skills [12] this centralised provision of services has been comprehensible. However, as the evidence for clinical utility of genetics/genomics in rare disease has emerged [13, 14] and, in many cases, provision of care now falls within the remit of nongenetic clinicians, is increasingly seen as mainstream [15]. Reduction in sequencing costs [16], increased public awareness of genetics [17], and dissatisfaction with the diagnostic odyssey [18] further fuel demands for equity of care. With these shifts in what genetics/genomics can offer, and public expectation of genetics/genomics, comes the need to consider equity of access across the wider population. Combining the uptick in the genetic/genomic clinical offerings and the increased expectation of availability of services, forms a need to ensure widespread availability of genetic/genomic services across diverse geographical localities.

The aim of this systematic review was to reveal what is known about geographical (in) equity in accessing clinical genomic or genetic services for people with a non-cancer related rare disease. Specifically, our objective was to identify barriers and enablers of geographical equity in accessing clinical genomic or genetic services.

Methods

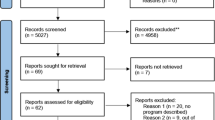

The literature search conducted followed PRISMA guidelines [19]. Search dates ran from January 2010 to July 2021. On the advice of a health services specialist librarian the databases Medline, EMBASE and PubMed were searched. Search terms were selected through exploration of MeSH terms, consideration of key words in current articles on geographical inequity and suggestions of expert researchers in the field. Terms included: [(rural OR remote OR regional OR metro/metropolitan OR urban) AND (‘clinical genetic*’ OR ‘genom* test*’ OR exom* test OR ‘genetic service’) AND (‘geograph* equit*’ OR inequal* OR accessibility OR ‘service provision’)]. The full search can be found in supplementary file 1. Articles were downloaded (N = 1824) into Endnote X9, a bibliographic database. We discarded duplicates and incomplete references (n = 379) leaving 1445 papers for inclusion. Mining reference lists did not reveal additional articles for inclusion.

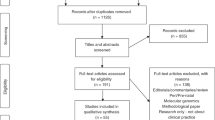

Three reviewers (KA, NV and SB) independently analysed 17.5% (n = 250) of the same title and abstracts, applying inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1). We included empirical, human research focused on geographical access to genetic or genomics services for rare disease, including telehealth/telegenetics and excluded commentaries, reviews and opinion pieces. We also excluded articles focused solely on non-germline disease those that only reported the experience of either rural or urban communities and those not in English.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria were refined early in the title and abstract screening process. The Fleiss’ Kappa statistic was calculated to measure inter-rater reliability, achieving k = 0.82 which is interpreted as ‘substantial agreement’ [20]. Following this assessment, the remaining 1174 articles were screened by three of the authors (KA, NV and SB) with weekly discussion across the team regarding any challenging articles. The full-text of the resulting 81 articles were assessed (KA, NV and SB), with 56 discarded as not meeting the inclusion criteria. The remaining 25 were further assessed for quality using the Hawker Tool [21] with five articles discarded on the basis of poor reporting of bias or ethical issues. The final 20 full-text articles to be included in the review were then analysed. The full search strategy is shown in Fig. 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram adapted from Moher et al. [19].

Data analysis

We adopted an inductive thematic analysis approach [22] to provide structure to the analysis. First the authors familiarised themselves with the full text articles independently before generating themes. Themes were refined by three authors (KA, NV and SB) through a series of discussions. Once themes were established one author (SB) completed the coding with regular review from the team.

Results

From the 20 papers in our search, the mainstay were from the USA (n = 12) though one article was a comparison with Malaysia. Four articles were from the UK, two based in Canada and one each from Brazil and Mexico. Most articles were published in 2019/2020 (n = 9) with four published in 2015/6 and seven pre-2013. Participants in the studies were either families or patients (n = 6), health care providers or policy makers (n = 3), genetic teams (i.e. clinicians and laboratory scientists) (n = 4) and specifically genetic counsellors (n = 5) and clinical geneticists (n = 1), with one paper incorporating the views of consumers, genetic professionals and the public. The majority of the studies were quantitative (n = 12) with five mixed methods and three qualitative studies. The aims for the studies varied. Many articles investigated the landscape of service provision (n = 10), seven specifically examined issues of equity and access to genetic/genomic services including outreach clinics and referral patterns. Three reported the views of practitioners and families on current genetic/genomic service provision. For more detail see Table 2.

Themes

We identified four themes, (i) Current service model design (ii) Logistical issues facing clinicians and communities, (iii) Workforce capacity and capability and (iv) Rural culture and consumer beliefs. Across the four themes, more barriers were reported than enablers. Here we present the barriers and enablers to equitable service provision identified within each theme.

-

i.

Current service model design: Extant models for service delivery compromise, ‘both the efficiency (allocating resources in accordance with levels of need) and equity (equal service provision for equal need) of resource utilisation’ leading to inequality in genetic service provision for rural communities [23, 24]. Systemic issues were reported to perpetuate the provision of existing service models e.g. distribution of genetic workforce, centred in urban areas [25,26,27] and lack of investment in rural services [28]. It has been recognised that calculating demand for genetic services, and so developing an appropriate service model, can be challenging [29]: there are numerous variables to be considered such as, awareness of services, referral patterns and geographical location [29]. However, to date, the design of service models was reported to have been piecemeal, dependent on assumptions of need and advocacy of local communities [30, 31] reinforced by a lack of local provider and community knowledge about genetic services [32].

Nevertheless, there is a desire to see geographically equitable services [23, 33]. The first step reported for initiating change in service models is a needs assessment and then creation of locally appropriate strategies [24, 34, 35]. There was clear evidence of a range of non-traditional service models being proposed to promote equity of service provision, including telegenetic services [27, 36, 37] group based counselling [27, 33] and delivery of genetic services via a regional genetics model [25, 38].

-

ii.

Logistical issues facing clinicians and communities: Day to day systemic challenges to delivery or receipt of geographically equitable genetic/genomic services were experienced at all levels e.g. patients, communities, health care provider, organisation [25]. The duration of travel for those travelling into genetic services from rural communities, and in particular those dependent on public transport were reported to impact on equity of service provision [23, 31]. One provider reported, ‘There are some folks who lack the organization, the money, or the car to drive [5 h]. It’s just beyond them. They’re not going to be able to do that.’ [31]. The time required to access a genetic service can then leave patients with additional unwanted opportunity costs such as, taking time off work (linked with job security) and challenges finding childcare [36, 39]. A lack of insurance and ongoing chronic illness were also associated with unmet need [40]. Service provider barriers to the implementation of locally appropriate services were also reported. Cost, accessibility to equipment and sustainable billing procedures were all often noted [27, 33, 35, 37, 38] with Vieira [28] relating challenges with the transportation of samples from rural areas in Brazil.

Overcoming logistical issues was largely focused on service providers, though service models of telephone and telemedicine services were suggested in order to reduce travel distance and time for patients [23, 33]. The need to support rural service providers was stressed, with technical support for services such as telegenetics proposed [25, 37, 38]. While innovative service models may provide a way to overcome logistical issues for rural communities, service providers faced challenges with sustainable billing systems to ensure reimbursement [27, 35, 39]).

-

iii.

Workforce capacity and capability: The capacity of rural service providers to engage with genetics was reported to be curbed by the challenges of keeping up to date. Several papers identify that rural service providers deliver more generalist service than their urban equivalents, limiting the potential for genetic/genomic expertise [25, 30, 38]. The absence of genetic/genomic knowledge is further compounded by a lack of informal liaison with colleagues and follow up contact with specialists [38]. A deficit of rural practitioner awareness, knowledge and skills of genetic services was reported, compounded by insufficient time to embed genetics into their workload and inadequate guidelines for management of genetic conditions [27, 38, 41]. In particular, Bernhardt [41] notes a shortage of providers to request genetic testing in rural settings, a lack of local knowledge on how to navigate the testing pathway and finally a paucity of rural provider knowledge on how to interpret genetic results.

A common theme to alleviate some of the workforce issues was to increase the size of the genetics workforce [34, 38, 41]. Also suggested was the promotion of awareness, amongst rural providers, of the role for genetic service and developing supporting partnerships/ accessibility between genetic and nongenetic providers [25, 27, 32, 37, 38, 41]. Similarly, industry sponsorship for attending continuing education activities related to genetics was proposed, though there was caution with the risk of bias [38].

-

iv.

Rural culture and consumer beliefs: There was little discussion about the impact of rural culture though Harding [38] does make reference to rural primary care providers’ ethos of ‘doing without’ with concern that this approach could limit the implementation of new diagnostic and management approaches such as incorporating genetic/genomics into care. Consumer concerns about genetic/genomics included the belief that the test was expensive and would not be covered by health insurance (with some participants reporting that insurance would not fund testing), lack of understanding of genetics, potential for impact on insurance, and limited awareness about management options [41]. A lack of community knowledge and awareness of the value of genetic services was also identified [27, 32, 38, 41].

Holloway’s [42] study found that establishing satellite genetic counselling clinics did not improve attendance, implying distance is only one obstacle for patients accessing genetic/genomic care. Although it was noted that there is a lack of flexibility in traditional service models [36], others have reported specific challenges when initiating change in rural areas [35, 37]. Conversely, Penon-Portmann [29] reported that many people travelled further than their nearest genetics provider which can be in part due to patient preference but also associated with their insurance requirements/insurance issues, specialisation of the provider and waiting times. Several papers provided a call to raise awareness of the benefits of genetics/genomics in order to demystify the clinical ‘offer’ from this speciality [34, 41].

Discussion

Themes identified from this review, (i) Current service model design (ii) Logistical issues facing clinicians and communities, (iii) Workforce capacity and capability and (iv) Rural culture and consumer beliefs describe the barriers and enablers identified for provision of a geographically equitable genetic/genomic service. First, current service designs were rarely reported to be fit for purpose for providing geographically equitable care. Second, both clinicians and their populations experienced practical challenges in delivering and receiving care. Third, the current capacity of genetic and nongenetic staff is well below their ability to deliver equitable services. Additionally, nongenetic staff capability was also found to be lacking both knowledge and skills to deliver genetic/genomic services. Finally, in line with other specialities, the influence of rurality was reported to impact expectations of service provision and receipt [43]. Figure 2 maps the identified barriers and enablers.

Barriers identified in this review were frequently common to both urban and rural practitioners and patients. For example, establishing sustainable reimbursement models and accessing genetic/genomic knowledge and skills. However, the impact of these barriers was often exacerbated for rural communities [44]. Rural communities often face adversity and challenges to their wellbeing [45]. Many rural residents experience ‘rural self reliance’ [46] whereby they have to access care from a healthcare system that promotes personal responsibility while providing minimal social support. A consequence of this may be that rural patients make less use of services such as genetic/genomics where key areas of focus include support, prevention and care for the individual with rare disease. Additionally, rural clinicians have a lack of immediate support and opportunities to develop relationships with genetic professionals for clinicians and the challenge of carrying a more generic caseload [38]. Many of the barriers reported were systemic long-standing challenges, for example, a historically ad hoc approach to service design. Genetic/genomic service models will have been designed before the advent of clinical genomics and dependent on in person patient assessment. This review found the advances in genetic/genomic knowledge and increasing complexity of clinical genetics/genomics may mean that delivery of genomic services may be better suited to a hybrid model with a combining genetic counsellors, telehealth, supported local nongenetic specialists and clinical geneticists accessible for advice and complex cases [25, 33, 37]. There were calls for needs assessments to establish more geographically equitable services, however, this would only be the first step and would need following up with policy and action.

Solutions reported included increasing the number of genetic professionals. However, with a finite health resources budget, any increase in one staff group would likely require consideration of what to defund. As the use of genomic testing is increasingly integrated into the healthcare system, it will be essential for service models to evolve to provide support for local health professions so that they are equipped to meet the needs of families with rare disease. Interestingly, many papers called for the use of new innovative models of care, citing various telehealth approaches to help reduce travel distances for rural communities. While there have been some challenges in the uptake of these approaches, the adoption of many will have been accelerated through COVID-19 [46, 47]. It is essential for the purpose of geographical equity of service provision that many of these pandemic lessons are continued into routine care. Other solutions called for an increase in genetic/genomic knowledge and awareness for both the community and the clinician. Clarifying what clinical genetic/genomic services can provide for different clinical specialities is essential to establishing equitable service provision. There was a call for coordinated national approaches to education, for example in Canada, to develop clinicians’ genetic/genomic knowledge and skills [48].

Barriers to equitable service provision identified from the literature are noted in Fig. 2 and hypothetically linked with potential enablers. Barriers are distributed across consumers, clinicians and organisational settings though relatively few enablers are noted directly for patients and the community. Additional enablers may be present though not reported in the papers from this review.

Limitations

Our study focused on rare disease and therefore did not take in the oncology or other clinical speciality literature on geographical inequity. A further study may be of benefit to highlight challenges specific to these fields. The majority of articles were from the USA (n = 12), potentially swaying the discussion to factors relevant to that healthcare system e.g. reimbursement. Only seven papers included the consumer perspective suggesting this aspect would benefit from further investigation. There were relatively few qualitative papers (n = 6) implying there exists additional perspectives to be studied. Figure 2 demonstrates barriers and enablers to accessing genetic/genomic services for people with rare disease from the perspective of consumers, clinicians and organisations. Qualitative studies could provide valuable insights into why the barriers exist and, most importantly, identify targeted strategies to address specific barriers which may include the need for policy changes [49]. Finally, we did not define a measure of urbanity or rurality, accepting the definitions provided in each paper.

Conclusion

Many of the challenges for equitable service provision were conflated with non-geographical factors e.g. health literacy [34], awareness (and so interest) of genetic/genomics for both patients and physicians [38], health insurance [29] all of which were reported to diminish in more rural communities. While this study focused on rare disease, many of the lessons are transferable into other clinical settings e.g. cancer and other specialist services e.g. transplant services. To achieve the goal of geographically equitable genetic/genomic services the next step for many service providers is to undertake a needs assessment. Determining the unmet need across the locality should be rapidly followed by the co-design, implementation and evaluation of community appropriate innovative service models. While genetics/genomics is a relatively new clinical speciality, it has a prime opportunity to adopt innovative models of care to ensure all communities regardless of where they live, have the opportunity to benefit from genetic/genomic services.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Dummer TJB. Health geography: supporting public health policy and planning. Can Med Assoc J. 2008;178:1177–80.

National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Health Care Services; Committee on Health Care Utilization and Adults with Disabilities. Factors that affect health-care utilization. In: Health-care utilization as a proxy in disability determination. Washington DC: National Academies Press (US); 2018.

Moy E, Garcia MC, Bastian B, Rossen LM, Ingram DD, Faul M, et al. Leading causes of death in nonmetropolitan and metropolitan areas, 1999–2014, CDC. Morbid Mortal Week Rep. 2017;66.

Henley SJ, Jemal A. Rural cancer control: bridging the chasm in geographic health inequity. HHS Public Access. 2018;27:1248–51.

Rocha TAH, Da Silva NC, Amaral PV, Barbosa ACQ, Rocha JVM, Alvares V, et al. Addressing geographic access barriers to emergency care services: a national ecologic study of hospitals in Brazil. Int J Equity Health. 2017;16:1–10.

Neale J, Tompkins C, Sheard L. Barriers to accessing generic health and social care services: a qualitative study of injecting drug users. Health Soc Care Community. 2008;16:147–54.

Jacobs B, Ir P, Bigdeli M, Annear PL, Van, Damme W. Addressing access barriers to health services: an analytical framework for selecting appropriate interventions in low-income Asian countries. Health Policy Plan. 2012;27:288–300.

Bellaiche MMJ, Fan W, Walbert HJ, McClave EH, Goodnight BL, Sieling FH, et al. Disparity in access to oncology precision care: a geospatial analysis of driving distances to genetic counselors in the U.S. Front Oncol. 2012;11:689927. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2021.689927.

Gardner B, Doose M, Sanchez JI, Freedman AN, Moor JSD. Distribution of genomic testing resources by oncology practice and rurality: a nationally representative study. JCO Precis Oncol. 2021;5:1060–8. https://doi.org/10.1200/po.21.00109.

National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. Understanding disparities in access to genomic medicine. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2018. 126.

Barwell JG, Sullivan RBGO, Mansbridge LK, Lowry JM, Dorkins HR. Challenges in implementing genomic medicine: the 100,000 Genomes Project. J Transl Genet Genom. 2018;2:13.

Best S, Brown H, Stark Z, Long JC, Ng L, Braithwaite J, Taylor N. Teamwork in clinical genomics: A dynamic sociotechnical healthcare setting. J Eval Clin Pract. 2021;27:1369–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.13573. Epub 2021 May 5.

Stark Z, Dolman L, Manolio TA, Ozenberger B, Hill SL, Caulfied MJ, et al. Integrating genomics into healthcare: a global responsibility. Am J Hum Genet. 2019;104:13–20.

Wise AL, Manolio TA, Mensah GA, Peterson JF, Roden DM, Tamburro C, et al. Genomic medicine for undiagnosed diseases. Lancet. 2019;394:533–40.

Manolio TA, Chisholm RL, Ozenberger B, Roden DM, Williams MS, Wilson R, et al. Implementing genomic medicine in the clinic: the future is here. Genet Med. 2013;15:258–67.

Mattick JS, Dziadek MA, Terrill BN, Kaplan W, Spigelman AD, Bowling FG, et al. The impact of genomics on the future of medicine and health. Med J Aust. 2014;201:17–20.

Borzekowski DL, Guan Y, Smith KC, Erby LH, Roter DL. The Angelina effect: immediate reach, grasp, and impact of going public. Genet Med. 2014;16:516–21.

Carmichael N, Tsipis J, Windmueller G, Mandel L, Estrella E. “Is it going to hurt?” The impact of the diagnostic odyssey on children and their families. J Genet Couns. 2015;24:325–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-014-9773-9. Epub 2014 Oct 4.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman D TPGroup. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097.

Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159.

Hawker S, Payne S, Kerr C, Hardey M, Powell J. Appraising the evidence: reviewing disparate data systematically. Qual Health Res. 2002;12:1284–99.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101.

Boothe E, Greenberg S, Delaney CL, Cohen SA. Genetic counseling service delivery models: a study of genetic counselors’ interests, needs, and barriers to implementation. J Genet Couns. 2020:1–10.

Harrison M, Birch S, Eden M, Ramsden S, Farragher T, Payne K, et al. Variation in healthcare services for specialist genetic testing and implications for planning genetic services: the example of inherited retinal dystrophy in the English NHS. J Community Genet. 2015;157–65.

Kaye C, Bodurtha J, Edick M, Ginsburg S, Keehn A, Lloyd-puryear M, et al. Regional models of genetic services in the United States. Genet Med [Internet]. 2020;22:381–8. Available from https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-019-0648-1.

Triebold M, Skov K, Erickson L, Olimb S, Puumala S, Wallace I, et al. Geographical analysis of the distribution of certified genetic counselors in the United States. J Genet Couns. 2020;1–9.

Villegas C, Haga SB. Access to genetic counselors in the Southern United States. J Pers Med. 2019;9:33. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm9030033.

Vieira TP, Sgardioli IC, Gil-da-silva-lopes VL. Genetics and public health: the experience of a reference center for diagnosis of 22q11. 2 deletion in Brazil and suggestions for implementing genetic testing. J Community Genet. 2013;4:99–106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12687-012-0123-z.

Penon-Portmann M, Chang J, Cheng M, Shieh JT. Genetics workforce: distribution of genetics services and challenges to health care in California. Genet Med. 2020;22:227–31.

Burton H, Alberg C, Moore AT. Genetics in ophthalmology: equity in service provision? J Public Health (Oxf). 2010;32:259–66. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdp110.

Senier L, Kearney M, Orne J. Using public-private partnerships to mitigate disparities in access to genetic services: lessons from Wisconsin. Adv Med Social. 2015;16:269–305.

Qian E. A comparative study of patients’ perceptions of genetic and genomic medicine services in California and Malaysia. J Community Genet. 2019;10:351–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12687-018-0399-8.

Cohen SA, Huziak RC, Gustafson S, Grubs RE. Analysis of advantages, limitations, and barriers of genetic counseling service delivery models. J Genet Couns. 2016;25:1010–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-016-9932-2.

Bucio D, Bustamante CD. A genetic counseling needs assessment of Mexico. Mol Genet Genom Med. 2019;7:e668. https://doi.org/10.1002/mgg3.668.

Cohen SA, Marvin ML, Riley BD, Vig HS, Rousseau JA, Gustafson SL. Identification of genetic counseling service delivery models in practice: a report from the NSGC Service Delivery Model Task Force. J Genet Couns. 2013;22:411–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-013-9588-0.

Hawkins AK, Creighton S, Hayden MR. When access is an issue: exploring barriers to predictive testing for Huntington disease in British Columbia, Canada. Eur J Hum Genet. 2013;21:148–53. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2012.147.

Terry AB, Wylie A, Raspa M, Vogel B, Sanghavi K, Djurdjinovic L, et al. Clinical models of telehealth in genetics: a regional telegenetics landscape. J Genet Couns. 2019;28:673–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/jgc4.1088.

Harding B, Webber C, Ruhland L, Dalgarno N, Armour CM, Birtwhistle R, et al. Primary care providers’ lived experiences of genetics in practice. J Community Genet. 2019;10:85–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12687-018-0364-6.

Dorfman E, Trinidad SB, Morales C, Howlett K, Burke W, Woodahl E. Pharmacogenomics in diverse practice settings: implementation beyond major. Pharmacogenomics. 2015;16:227–37.

Smith AJ, Oswald D, Bodurtha J. Trends in unmet need for genetic counseling among children with special health care needs, 2001–2010. Acad Pediatr. 2015;15:544–50.

Bernhardt BA, Zayac C, Pyeritz RE. Why is genetic screening for autosomal dominant disorders underused in families? The case of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Genet Med. 2011;13:812–20. https://doi.org/10.1097/GIM.0b013e31821d2e6d.

Holloway SM, Lampe AK, Lam W. Paediatric referral and attendance rates for the clinical genetics service in south-east Scotland--a comparison of a regional clinic with satellite clinics. Scott Med J. 2010;55:10–3. https://doi.org/10.1258/RSMSMJ.55.1.10.

Blaes AH, Patricia IJ, McKay K, Riley D, Jatoi I, Trentham-Dietz A, et al. Factors associated with genetic testing in a cohort of breast cancer survivors. Breast J. 2019;25:1241–4.

Green RF, Ari M, Kolor K, Dotson WD, Bowen S, Habarta N, et al. Evaluating the role of public health in implementation of genomics-related recommendations: a case study of hereditary cancers using the CDC Science Impact Framework. Genet Med. 2019;21:28–37.

Lawrence-Bourne J, Dalton H, Perkins D, Farmer J, Luscombe G, Oelke N, et al. What is rural adversity, how does it affect wellbeing and what are the implications for action? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:7205.

Page-Carruth A, Windsor C, Clark M. Rural self-reliance: the impact on health experiences of people living with type II diabetes in rural Queensland, Australia. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being. 2014;9:24182. https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v9.24182.

Brown EG, Watts I, Beales ER, Maudhoo A, Hayward J, Sheridan E, et al. Videoconferencing to deliver genetics services: a systematic review of telegenetics in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. Genet Med. 2021;23:1438–49. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-021-01149-2. Epub 2021 Apr 6.

Bonter K, Desjardins C, Currier N, Pun J, Ashbury FD. Personalised medicine in Canada: a survey of adoption and practice in oncology, cardiology and family medicine. BMJ Open. 2011;1:1–7.

Hamilton AB, Finley EP. Qualitative methods in implementation research: an introduction. Psychiatry Res. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112516.

Acknowledgements

The authors declare no competing financial interests in relation to the study described in the manuscript. Our study was funded through Australian Genomics, via an NHMRC Targeted Call for Research grant (GNT1113531): ‘Preparing Australia for Genomic Medicine’. The funders played no part in the study design; data collection, analysis, and interpretation; in the writing of the manuscript or in the decision to submit this manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SB was responsible for designing the review protocol, writing the protocol and report, screening eligible studies, extracting and analysing data, interpreting results, and lead the writing. NV supported designing the review protocol, screening eligible studies, extracting and analysing data, interpreting results and supported writing up the findings. KA liaised with the librarian, ran the searches, screening eligible studies, extracting and analysing data, interpreting results and supported writing up the findings. FC supported designing the protocol, provided expert opinion and criticism and writing up the findings. SMW supported designing the protocol, provided expert opinion and criticism and writing up the findings

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Best, S., Vidic, N., An, K. et al. A systematic review of geographical inequities for accessing clinical genomic and genetic services for non-cancer related rare disease. Eur J Hum Genet 30, 645–652 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-021-01022-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-021-01022-5

This article is cited by

-

International Undiagnosed Diseases Programs (UDPs): components and outcomes

Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases (2023)

-

Data saves lives: optimising routinely collected clinical data for rare disease research

Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases (2023)

-

Genomic newborn screening for rare diseases

Nature Reviews Genetics (2023)

-

What matters to parents? A scoping review of parents’ service experiences and needs regarding genetic testing for rare diseases

European Journal of Human Genetics (2023)

-

2022: the year that was in the European Journal of Human Genetics

European Journal of Human Genetics (2023)