Abstract

Cascade testing is the process of offering genetic counseling and testing to at-risk relatives of an individual who has been diagnosed with a genetic condition. It is critical for increasing the identification rates of individuals with these conditions and the uptake of appropriate preventive health services. The process of cascade testing is highly varied in clinical practice, and a comprehensive understanding of factors that hinder or enhance its implementation is necessary to improve this process. We conducted a systematic review to identify barriers and facilitators for cascade testing and searched PubMed, CINAHL via EBSCO, Web of Science, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library for articles published from the databases’ inception to November 2018. Thirty articles met inclusion criteria. Barriers and facilitators identified from these studies at the individual-level were organized into the following categories: (1) demographics, (2) knowledge, (3) attitudes, beliefs, and emotional responses of the individual, and (4) perceptions of relatives, relatives’ responses, and attitudes toward relatives. At the interpersonal-level, barriers and facilitators were categorized as (1) family communication-, support- and dynamics-, and (2) provider-factors. Finally, barriers at the environmental-level relating to accessibility of genetic services were also identified. Our findings suggest that several individual, interpersonal and environmental factors may play a role in cascade testing. Future studies to further investigate these barriers and facilitators are needed to inform future interventions for improving the implementation of cascade testing for genetic conditions in clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cascade testing is the process of offering genetic testing to at-risk relatives of an individual who has been diagnosed with a genetic condition (i.e., the index patient or proband). This process is critical for timely initiation of risk-management strategies such as surveillance and prophylactic strategies, and is widely used in autosomal dominant conditions such as familial cancers and familial hypercholesterolemia. Clinical guidelines for these diseases recommend that cascade testing be offered to relatives of probands to identify cases [1,2,3]. Despite this, studies suggest that several genetic conditions remain underdiagnosed in the population [4,5,6], indicating that the implementation of cascade testing in clinical practice needs to be optimized.

To date, few studies have systematically reviewed the uptake of cascade testing in relatives of probands and the effectiveness of such interventions across various diseases. In a scoping review focused on the delivery of cascade testing for hereditary conditions, Roberts et al. provide a broad overview of cascade testing interventions, policy considerations, barriers and facilitators to their use and research gaps [7]. Based on their findings, several research gaps remain in the literature on cascade testing, including limited use of rigorous methods to test the efficacy of cascade testing programs and interventions. Understanding factors that influence whether probands disclose genetic information and whether relatives pursue genetic testing will be critical to design effective interventions to improve cascade testing. To address this need, we conducted an in-depth systematic review of the research literature to identify barriers and facilitators that may affect the uptake of cascade testing.

Methods information sources and search strategy

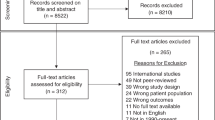

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) reporting guidelines [8] were followed for this study (Supplemental Material, Appendix A). The following databases: PubMed, CINAHL via EBSCO, Web of Science, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library were electronically searched for articles published from the database inception date to 18 November, 2018 using keywords and appropriate subject headings that captured the range of terms used synonymously with cascade testing (e.g., “cascade screening” and “familial genetic testing”). Complete search strategies are provided in Supplemental Material, Appendix B. Hand-searches were also performed by manually examining the references of relevant literature reviews to identify any additional studies that may have been missed due to incomplete or inaccurate indexing in the electronic search databases. All references were uploaded to Covidence Systematic Review software (https://www.covidence.org) [9], a systematic review management system for study selection.

Study selection

Two of four reviewers (MCR, NYW, SS, and WDD) independently reviewed each title and abstract for eligibility, and disagreements were resolved through discussion. The same procedure was repeated for full-text review. Articles that focused on the disclosure of genetic information to family members and the actual uptake of genetic testing by relatives were both included to comprehensively capture barriers and facilitators to cascade testing both from probands’ and the family members’ perspectives. Conference abstracts, meeting reports, literature reviews, guidelines, and simulation modeling studies were excluded. Articles relating to other types of genetic testing and disclosure (whole-population or universal genetic testing, parental disclosure of genetic testing to children, newborn/neonatal/pre-natal testing, or proband testing), those that lacked a methods section or relevant outcomes (no barriers/facilitators described, study focused on clinical outcomes for cascade testing only, or study did not explicitly study cascade testing) and those that only reported prevalence of genetic testing were also excluded.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data extraction forms were developed in Covidence using the PICOS framework for the following information: population (sample size and percentage of women), intervention (characteristics of the cascade testing intervention including disease area(s), whether counseling and resources related to cascade testing were provided, primary mediator of cascade testing), comparator (if applicable), outcomes (barriers and facilitators) and setting (country, scale, clinical, academic) [10]. Barriers and facilitators experienced either by proband or relatives in cascade testing were qualitatively described in some studies and, in others, were examined for their ability to predict relatives’ uptake of genetic testing or proband’s disclosure to relatives through methods like regression. Our coding used an inductive approach and reflected the language used by study authors. The forms were developed iteratively and piloted on a subset of five articles after which two reviewers independently extracted data from each study. Disagreements were resolved through discussion. Barriers and facilitators were organized according to the Social Ecological Model, a theoretical framework that allows for the examination of the interactions between personal and environmental factors on health behaviors [11].

The methodological quality of each study was assessed using the Mixed Method Appraisal Tool (MMAT), version 2018 [12]. Both reviewers independently assessed whether the study met the corresponding MMAT criteria for each study type (RCT, descriptive, observation, qualitative, or mixed-methods). Meta-analysis was not conducted given the significant heterogeneity in study design, populations, setting, and outcomes.

Results

Of the 4256 unique studies that were identified through database searching and hand-searching, 229 articles were assessed for full-text eligibility. Thirty articles [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42] were included in our analysis after excluding articles as per the inclusion and exclusion criteria (see Fig. 1 for PRISMA flow diagram).

Study characteristics for the included articles are available in Table 1. Twelve studies [13, 17, 22, 24,25,26, 28, 29, 35, 36, 38, 40] were conducted in the US while the remaining were conducted in Australia (n = 4) [14, 15, 19, 20], Europe (n = 9; 4 UK or parts of UK [23, 27, 31, 42], 4 Netherlands [21, 33, 34, 43], 1 France [39]), Asia (n = 4; 2 Israel [18, 41], 1 Vietnam [30], 1 Japan [16]), and South America (n = 1 from Brazil [37]). Most studies were conducted within a single-center (n = 12 [16, 17, 20, 22,23,24, 30, 34, 35, 37, 40, 41]), followed by national- (n = 10) [13, 14, 18, 21, 26, 29, 31, 33, 38, 43], regional- (n = 4) [19, 39, 40, 42], multi-center (n = 3) [27, 28, 36] and state- (n = 1) [25] level studies. The majority of studies (n = 18) [13, 14, 16,17,18,19, 25, 26, 28, 30, 33, 35,36,37,38,39,40,41] used a descriptive study design using survey/interview/case series/observational data, with a few qualitative studies (n = 9) [15, 21, 23, 24, 27, 29, 31, 42, 43] and mixed-method studies (n = 2) [20, 34] and one randomized controlled trial [22]. Studies spanned disease areas including familial hypercholesterolemia (n = 10) [13, 15, 19, 25, 30, 33, 35, 37, 42, 43], Lynch syndrome (n = 6) [16, 17, 21, 24, 28, 38], hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (n = 6) [18, 22, 29, 36, 40, 41], cystic fibrosis (n = 3) [20, 31, 39], inherited cardiac conditions (n = 2) [23, 27], Fragile X syndrome (n = 2) [26, 34], and long QT syndrome (n = 1) [14]. Only one study explicitly reported that counseling was included as a component of cascade testing [42], while two studies noted that resources to assist with cascade testing (letter, written material and information sheet) were provided to patients [23, 42]. In most studies, the stakeholder who contacted relatives was not explicitly defined (n = 16) [13, 14, 16, 18,19,20,21, 26,27,28,29, 31, 35, 36, 38, 39], with patients (n = 5) [22, 23, 34, 41, 44], study team members (n = 4) [24, 30, 40, 45], providers (n = 2) [17, 37] and members of a screening program (n = 3) [15, 33, 43] contacting relatives in the remaining studies. Three studies were conducted solely among women [13, 22, 36], one study was conducted solely among men [29], and six studies did not report the proportion of females in the study sample [20, 27, 30, 31, 34, 43]. Sixteen studies did not contain information about race and ethnicity of the study sample [14,15,16, 19,20,21, 23, 27, 30, 33, 34, 37, 39, 41,42,43, 45].

Overall, both reviewers indicated that studies met three or more criteria, with few studies falling below this threshold. Barriers and facilitators at the individual, interpersonal and environmental levels are summarized in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. Notably, no studies in our analysis investigated any environmental facilitators. Only significant and descriptive results from our analysis are described below. In addition, nonsignificant factors are presented in Table 3.

Individual barriers

Demographics

One study reported that having low income was negatively associated with uptake of genetic testing among relatives [26], while other studies reported positive associations with other demographic factors (presented under Facilitators).

Knowledge

Studies described low or perceived lack of knowledge among probands and/or relatives as a barrier for both disclosure [25] and uptake of testing [23, 27, 31]. Probands in two studies cited not knowing who was at risk for the disease as a barrier to disclosure [14, 40].

Attitudes, beliefs and emotional responses of the individual

A number of barriers for probands and/or relatives to disclosure were reported, including: actionability of results [25], religion [25], discomfort with topic [25], sadness [25], surprise [25], lack of trust in the genetic information presented [25], laziness [25], no dissemination plan [20], time needed to communicate [25], emotional or general difficulty in sharing information [14, 25, 35, 40], and a preference for doctors to explain [25]. Paternalism [43], psychological burden [43], anticipation of regret [33], location of relatives [27], low perceived susceptibility [23], attitudes toward genetic testing [23], and lack of motivation [15] were described by probands and/or relatives as barriers to uptake of genetic testing. High depression symptoms had a negative effect on disclosure by probands [22], while the presence of depression symptoms among probands had a negative association with uptake. A belief that costs outweighed benefits was described as a barrier to uptake by probands [17]. General privacy concerns [25, 28, 43], deferment or rejection of responsibility [15, 25, 35], anxiety or guilt [14, 20, 25, 27, 28], logistical concerns [16, 35, 44, 45], fear of discrimination in the context of marriage or employment [18, 35], and limited recall of diagnosis and competing pressures [20, 25, 27] were all described as barriers to disclosure and uptake by probands and/or relatives. Finally, lack of readiness for discussion among probands was described as barrier to uptake [18].

Perceptions of relatives, relatives’ reported responses, and attitudes toward relatives

Lack of concern or interest by relatives [18, 20, 25], the possibility of relatives not agreeing to testing [25], relatives not believing participants [25] and concern regarding family reaction [25] were described as barriers to disclosure among probands and/or relatives. Not wanting to upset relatives and family [14, 35], and lack of understanding [20, 25, 28, 35, 40] were described as barriers to disclosure among probands and/or relatives. Unwilling and uncaring attitudes of relatives [25, 27, 35, 40], relevance for relative’s stage of life [16, 20], and hostility toward advice or rejection [18, 25, 35] were described as barriers to disclosure and uptake among probands and/or relatives. Avoidance (or right not to know) [15, 20, 33, 43] and a perception that the relative appeared to be healthy [16] were barriers to uptake among probands and/or relatives.

Interpersonal barriers

Family communication, support, and dynamics

Emotional distance, estrangement, conflict, or resentment was described as a barrier among probands and/or relatives for both disclosure [21, 28] and uptake [18, 23, 42]. Similarly, not being in contact or not being emotionally close with family was described as a barrier among probands and/or relatives for both disclosure [21, 25, 35, 40] and uptake [16, 27]. General communication concerns was described as a barrier among probands and/or relatives for disclosure [25] and uptake [24, 27, 34]. In another study, no communication had a negative effect among probands on uptake of cascade testing [26]. A disappointing experience with disclosure early in the process was described as a barrier among probands and/or relatives for both disclosure [20] and uptake [31]. The impact on family relationship was described as a barrier among probands for disclosure [28]. The negative impact of disease on the family itself was described as a barrier among probands for uptake [34], and also reported to have a negative association among relatives for uptake [26]. Finally, language barriers among probands and/or relatives were barriers for disclosure [25].

Provider factors

Low provider awareness [29, 43] and lack of provider engagement [31] were described as barriers for probands and/or relatives for uptake of cascade testing.

Environmental barriers

Accessibility of genetic testing was the main environmental barrier studied in the literature. In two studies, probands and/or relatives described finances/cost [25, 43] or insurance coverage [25, 43] as barriers to both disclosure and genetic testing. In another study, relatives described finances, cost or insurance coverage as barriers to disclosure [35]. Access to genetic testing services was described as a barrier for probands and/or relatives for disclosure [20] and uptake [31]. Extra clinical referrals required to pursue genetic testing was also described as a barrier for probands and/or relatives for uptake [43].

Individual facilitators

Demographics

Older age was positively associated with disclosure among probands and/or relatives in one study [36]. Females had a positive association with disclosure (relatives) [22] and uptake of testing (proband and or relatives) [39]. Asian race of probands and/or relatives was positively associated with disclosure [36] and uptake [36]. Married individuals were more likely to engage both in disclosure (probands) [13] and uptake of testing (probands and/or relatives) [17]. High income of probands had a positive association with uptake of genetic testing by relatives in one study [13]. Last, high socioeconomic status of probands and/or relatives was associated with both disclosure and uptake of genetic testing in one study [36].

Clinical factors

Personal history of probands and/or relatives was positively associated with uptake [36] for probands and/or relatives in one study. Prior history of risk factors for relatives was described to be a facilitator for genetic testing [19]. Finally, receipt of unambiguous genetic test results by probands was positively associated with disclosure.

Attitudes, beliefs, and emotional responses of the individual

A need for emotional support from relatives was described as a facilitator in multiple studies for disclosure [20, 35, 40] and uptake [18] among both probands and/or relatives. A high satisfaction with the decision to undertake genetic testing was positively associated with both disclosure [36] and uptake [36] among both probands and/or relatives. Similarly, knowledge of screening and risk reduction recommendations was positively associated with disclosure among both probands and/or relatives [36]. Intrinsic motivation [21] and high levels of perceived susceptibility [21] were described as facilitators for disclosure among proband and/or relatives. In one study, high levels of perceived control [22] was positively associated with disclosure among probands. Lastly, probands and/or relatives indicated that feeling forced by circumstances [33] also enabled uptake of genetic testing.

Perceptions of relatives, relatives’ reported responses, and attitudes toward relatives

Prominently, a moral obligation toward relatives or a duty to inform was described in multiple studies as a facilitator for probands and/or relatives for both disclosure [14, 21, 35] and uptake [18, 31, 34, 42]. A desire to prevent harm in the family or duty to protect was described as a facilitator for probands and/or relatives for both disclosure [18, 35] and uptake [15, 27]. Relatives’ right to know (separate from duty to inform) [23, 24, 29, 34] and a belief that information would help in making medical or lifestyle decisions [14, 27, 31, 35] were also facilitators for probands and/or relatives for both disclosure and uptake. Concern for relatives was described as a facilitator for disclosure [29] and uptake [20, 23]. A perception of relatives having a positive opinion on genetic testing was positively associated with disclosure among probands. A need for help in understanding the disease was a facilitator for disclosure (probands) [28] and uptake (probands and/or relatives) [16]. A desire to prevent relatives from feeling the same sorrow [16] was also a facilitator for uptake among probands and/or relatives.

Interpersonal facilitators

Family communication, support, and dynamics

The degree of closeness was investigated in several studies. When the relatives were children, there was a positive effect on disclosure [22]. In one study, siblings, aunts and uncles were more likely to pursue genetic testing [39]. When the relatives were first-degree relatives of probands, there was a positive association with genetic testing [41]. Solidarity [33] and support [43] from family members were described as facilitators for uptake of genetic testing by probands and/or relatives. Encouraging relatives to get testing was described as a facilitator for disclosure (probands and/or relatives) [28] and uptake [34] (probands) [34]. Providing relatives with information about risk was described as a facilitator for disclosure among probands and/or relatives [14, 28]. Active and open communication was described as a facilitator for disclosure among probands and/or relatives [29].

Provider factors

Materials to pass to relatives (e.g., genetic counseling note, family letter) were described as facilitators for both disclosure (relatives) [35] and uptake (probands and/or relatives) [38, 42]. Assistance in identifying relatives at risk was described among probands as a facilitator for uptake [42], and among relatives for disclosure [35]. Assistance in making contact with relatives and a dissemination plan were described as facilitators for disclosure [21, 35] and uptake [15, 23, 24] among probands and/or relatives. A physician’s recommendation was described as a facilitator for both disclosure [21, 28, 40] and uptake [16] by probands and/or relatives. A referral to a genetics clinic [38] and provider follow-up [43] were described as facilitators for uptake among probands and/or relatives. Finally, speaking with a genetic counselor was described as a facilitator for disclosure by relatives [35].

Discussion

Several individual and interpersonal factors, and a few environmental factors, were described as barriers and facilitators to cascade testing for genetic conditions in studies included in our review. In particular, attitudes, beliefs and emotional responses both relating to the individual and their relatives were identified, with a large number of these factors reported in one study that used a survey design. Our findings suggest that there is a need to verify the role of these factors in the uptake of cascade testing using rigorous methods.

Factors relating to provider awareness and engagement were described as facilitators in included studies; conversely, lack of provider awareness and engagement were described as barriers in three studies. Previous studies evaluating cascade testing programs or interventions have shown that direct methods, where trained providers directly contact at-risk relatives of probands, are effective [46, 47]. Two studies [42, 43] included in this review examined the acceptability of direct vs. indirect approaches (where cascade testing is primarily patient-mediated) through qualitative methods, and findings from these studies indicate that even though direct methods may be more effective, patients expressed a preference for patient-mediated approaches as this emphasized autonomy and privacy, and was less threatening to relatives. Further, the regulatory landscape for provider-directed communication is not described in our included studies, and cannot be directly inferred (except in certain settings, such as the United States). Thus, the extracted facilitators from these two studies and others suggest several approaches for improving cascade testing in settings where a patient-mediated method is the norm, necessary (due to regulations) or preferred. In these settings, assistance in identifying at-risk relatives, creating a dissemination plan, receiving materials to pass on to relatives and follow-up were potential facilitators for cascade testing. These approaches could alleviate reported barriers regarding low or perceived lack of knowledge, as well as barriers such as not knowing who was at risk in the family.

Provider recommendation to share results with family was also described as a facilitator in several studies. This finding matches that of another study that examined non-directive approaches to counseling in families with BRCA1/2 gene variants, and suggested that more directive approaches are warranted in hereditary cancers, even if direct provider contact with relatives is not possible [48]. Overall, our results indicate that the role of the provider is critical in the process of cascade testing, and that the nature of provider engagement with patients and their relatives need to be optimized based on the environment and patient-preferences.

Family support, communication and dynamics play a key role in cascade testing, and several factors played a role either as barriers or facilitators. Indeed, it is well-known that genetic testing affects family relationships, with effects ranging from health benefits for relatives to strained relationships with family members. Interventions that strengthen family communication and increase family support, in addition to provider engagement, could optimize cascade testing. The process of genetic counseling typically incorporates psychosocial support for patients and their relatives, and interventions focused on enhancing family support and communication could be integrated in this process [49].

Our results also indicate that few studies have assessed factors outside the individual and interpersonal levels. In particular, contextual characteristics of the study setting and environmental barriers such as access to insurance, costs, etc. may be less relevant in countries with single payer-systems, but may play a more important role in countries such as the United States. Future work should examine the relative changeability and importance of multilevel barriers and facilitators for cascade testing. In addition it will be important not only to identify individual and interpersonal level determinants of cascade testing but also those on the environmental level (encompassing the organizational or institutional, community and public policy levels within the Social Ecological Model) to enable a comprehensive understanding of barriers and facilitators specific to various settings and contextual factors, as well as to build effective interventions.

Finally, studies across autosomal dominant and recessive disorders were included to capture barriers and facilitators to the process of cascade testing, whenever family communication and testing were explicitly studied. However, the motivation for cascade testing for variants that confer risk of developing disease (e.g., BRCA1/2 variants) versus those that confer risk for children inheriting a disease (e.g., cystic fibrosis) may drive the differences in the nature of individual and interpersonal barriers and facilitators described in our results.

Limitations

First, we performed a narrative synthesis of the literature, as a meta-analysis was not feasible given that studies in this area did not assess effect sizes of barriers and facilitators on cascade testing. Second, inconsistent terminology was used across studies for the factors investigated, so we were able to merge the extracted barriers and facilitators in only a few instances. Third, there is a potential for bias as we integrated findings from both quantitative and qualitative studies, a majority of studies used a descriptive study design, a majority of the barriers to disclosure were extracted from one study [25], and most of the non-demographic factors were described as barriers or facilitators, instead of being reported as effect-sizes. Fourth, as with any systematic review, it is possible that we may have missed relevant literature. Finally, from an ethical perspective, receiving all information necessary to make an informed decision about testing and being offered testing may be the most appropriate measures for evaluating interventions for cascade testing. However, we used family communication and receiving genetic testing as approximate outcomes, because many studies did not sufficiently discriminate between these distinct processes in outcome measurement. Thus, some barriers from our results (e.g., fear of negative impact on family relationships affecting uptake) may arise from receiving information about testing, being offered testing, but ultimately choosing not to engage in testing.

Conclusions

Findings from this systematic review can inform additional formative work. Future research should examine the role of identified barriers and facilitators for cascade testing using rigorous, theory-informed methods. Taken together this work can inform future development of interventions to improve cascade testing outcomes.

References

Gupta S, Ahnen DJ, Chen L-M, Chung DC, Cooper G, Early DS, et al. NCCN guidelines Version 3. 2019 genetic/familial high-risk assessment: Colorectal [Internet]. [cited 2019 Dec 18]. 2019. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/genetics_colon.pdf.

Cascade Testing: Testing Women for Known Hereditary Genetic Mutations Associated With Cancer - ACOG [Internet]. [cited 2019 Dec 18]. https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Gynecologic-Practice/Cascade-Testing-Testing-Women-for-Known-Hereditary-Genetic-Mutations-Associated-With-Cancer.

Goldberg AC, Hopkins PN, Toth PP, Ballantyne CM, Rader DJ, Robinson JG, et al. Executive summary familial hypercholesterolemia: screening, diagnosis and management of pediatric and adult patients clinical guidance from the national lipid association expert panel on familial hypercholesterolemia background and rationale. J Clin Lipidol. 2011;5:1–8.

Beitsch PD, Whitworth PW, Hughes K, Patel R, Rosen B, Compagnoni G, et al. Underdiagnosis of hereditary breast cancer: are genetic testing guidelines a tool or an obstacle? J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:453–60.

Abul-Husn NS, Manickam K, Jones LK, Wright EA, Hartzel DN, Gonzaga-Jauregui C, et al. Genetic identification of familial hypercholesterolemia within a single U.S. health care system. Science. 2016;354:aaf7000.

Hampel H, De La Chapelle A. The search for unaffected individuals with lynch syndrome: do the ends justify the means? Cancer Prev Res. 2011;4:1–5.

Roberts MC, Dotson WD, DeVore CS, Bednar EM, Bowen DJ, Ganiats TG, et al. Delivery of cascade screening for hereditary conditions: a scoping review of the literature. Health Aff. 2018;37:801–8.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:1006–12.

Covidence Knowledge Base [Internet]. [cited 2019 Oct 21]. https://support.covidence.org/help.

Schardt C, Adams MB, Owens T, Keitz S, Fontelo P. Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Med Inf Decis Mak. 2007;7:16.

Golden SD, Earp JAL. Social ecological approaches to individuals and their contexts: twenty years of health education & behavior health promotion interventions. Health Educ Behav. 2012;39:364–72.

Nha HONG Q, Pluye P, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, et al. MIXED METHODS APPRAISAL TOOL (MMAT) VERSION 2018 User guide.

Benson G, Witt DR, VanWormer JJ, Campbell SM, Sillah A, Hayes SN, et al. Medication adherence, cascade screening, and lifestyle patterns among women with hypercholesterolemia: Results from the WomenHeart survey. J Clin Lipidol. 2016;10:937–43.

Burns C, McGaughran J, Davis A, Semsarian C, Ingles J. Factors influencing uptake of familial long QT syndrome genetic testing. Am J Med Genet A. 2016;170a:418–25.

Hardcastle S, Legge E, Laundy C, Egan S, French R, Watts G, et al. Patients’ Perceptions and Experiences of Familial Hypercholesterolemia, Cascade Genetic Screening and Treatment. Int J Behav Med. 2015;22:92–100.

Ishii N, Arai M, Koyama Y, Ueno M, Yamaguchi T, Kazuma K, et al. Factors affecting encouragement of relatives among families with Lynch syndrome to seek medical assessment. Fam Cancer. 2011;10:649–54.

Lerman C, Hughes C, Trock BJ, Myers RE, Main D, Bonney A, et al. Genetic testing in families with hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer. JAMA. 1999;281:1618–22.

Lieberman S, Lahad A, Tomer A, Koka S, BenUziyahu M, Raz A, et al. Familial communication and cascade testing among relatives of BRCA population screening participants. Genet Med. 2018;20:1446–54.

Maxwell SJ, Molster CM, Poke SJ, O’Leary P. Communicating familial hypercholesterolemia genetic information within families. Genet Test Mol Biomark. 2009;13:301–6.

McClaren BJ, Aitken M, Massie J, Amor D, Ukoumunne OC, Metcalfe SA. Cascade carrier testing after a child is diagnosed with cystic fibrosis through newborn screening: investigating why most relatives do not have testing. Genet Med. 2013;15:533–40.

Mesters I, Ausems M, Eichhorn S, Vasen H. Informing one’s family about genetic testing for hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC): a retrospective exploratory study. Fam Cancer. 2005;4:163–7.

Montgomery SV, Barsevick AM, Egleston BL, Bingler R, Ruth K, Miller SM, et al. Preparing individuals to communicate genetic test results to their relatives: report of a randomized control trial. Fam Cancer. 2013;12:537–46.

Ormondroyd E, Oates S, Parker M, Blair E, Watkins H. Pre-symptomatic genetic testing for inherited cardiac conditions: a qualitative exploration of psychosocial and ethical implications. Eur J Hum Genet. 2014;22:88–93.

Pentz RD, Peterson SK, Watts B, Vernon SW, Lynch PM, Koehly LM, et al. Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer family members’ perceptions about the duty to inform and health professionals’ role in disseminating genetic information. Genet Test. 2005;9:261–8.

Campbell M, Humanki J, Zierhut H. A novel approach to screening for familial hypercholesterolemia in a large public venue. J Community Genet. 2017;8:35–44.

Raspa M, Edwards A, Wheeler A, Bishop E, Bailey D. Family communication and cascade testing for fragile X syndrome. J Genet Couns. 2016;25:1075–84.

Smart A. Impediments to DNA testing and cascade screening for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and Long QT syndrome: a qualitative study of patient experiences. J Genet Couns 2010;19:630–9.

Stoffel EM, Ford B, Mercado RC, Punglia D, Kohlmann W, Conrad P, et al. Sharing genetic test results in Lynch syndrome: communication with close and distant relatives. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:333–8.

Suttman A, Pilarski R, Agnese DM, Senter L. “Second-class status?” insight into communication patterns and common concerns among men with hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome. J Genet Couns. 2018;27:885–93.

Truong TH, Kim NT, Nguyen MNT, Pang J, Hooper AJ, Watts GF, et al. Homozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia in Vietnam: case series, genetics and cascade testing of families. Atherosclerosis. 2018;277:392–8.

Ulph F, Cullinan T, Qureshi N, Kai J. Parents’ responses to receiving sickle cell or cystic fibrosis carrier results for their child following newborn screening. Eur J Hum Genet. 2015;23:459–65.

Louter L, Defesche J, Roeters van Lennep J. Cascade screening for familial hypercholesterolemia: Practical consequences. Atheroscler Suppl. 2017;30:77–85.

van Maarle MC, Stouthard ME, Marang-van de Mheen PJ, Klazinga NS, Bonsel GJ. How disturbing is it to be approached for a genetic cascade screening programme for familial hypercholesterolaemia? Psychological impact and screenees’ views. Community Genet. 2001;4:244–52.

Van Rijn MA, De Vries BBA, Tibben A, Van Den Ouweland AMW, Halley DJJ, Niermeijer MF. DNA testing for fragile X syndrome: Implications for parents and family. J Med Genet. 1997;34:907–11.

Wurtmann E, Steinberger J, Veach PM, Khan M, Zierhut H. Risk communication in families of children with familial hypercholesterolemia: identifying motivators and barriers to cascade screening to improve diagnosis at a Single Medical Center. J Genet Couns. 2018;28:50–8.

Cheung EL, Olson AD, Yu TM, Han PZ, Beattie MS. Communication of BRCA results and family testing in 1,103 high-risk women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2010;19:2211–9.

de Souza Silva PR, Jannes CE, Oliveira TGM, Gómez LMG, Krieger JE, Santos RD, et al. Predictors of family enrollment in a genetic cascade screening program for familial hypercholesterolemia. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2018;111:578–84.

Dilzell K, Kingham K, Ormond K, Ladabaum U. Evaluating the utilization of educational materials in communicating about Lynch syndrome to at-risk relatives. Fam Cancer. 2014;13:381–9.

Dugueperoux I, L’Hostis C, Audrezet MP, Rault G, Frachon I, Bernard R, et al. Highlighting the impact of cascade carrier testing in cystic fibrosis families. J Cyst Fibros. 2016;15:452–9.

Finlay E, Stopfer JE, Burlingame E, Evans KG, Nathanson KL, Weber BL, et al. Factors determining dissemination of results and uptake of genetic testing in families with known BRCA1/2 mutations. Genet Test. 2008;12:81–91.

Hagoel L, Dishon S, Almog R, Silman Z, Bisland-Becktell S, Rennert G. Proband family uptake of familial-genetic counselling. Psychooncology. 2000;9:522–7.

Hallowell N, Jenkins N, Douglas M, Walker S, Finnie R, Porteous M, et al. Patients’ experiences and views of cascade screening for familial hypercholesterolemia (FH): a qualitative study. J Community Genet. 2011;2:249–57.

van El CG, Baccolini V, Piko P, Cornel MC. Stakeholder views on active cascade screening for familial hypercholesterolemia. Healthcare. 2018;6:108.

Hallowell N, Jenkins N, Douglas M, Walker S, Finnie R, Porteous M, et al. A qualitative study of patients’ perceptions of the value of molecular diagnosis for familial hypercholesterolemia (FH). J Community Genet. 2017;8:45–52.

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Heal Care. 2007;19:349–57.

Suthers GK, Armstrong J, McCormack J, Trott D. Letting the family know: balancing ethics and effectiveness when notifying relatives about genetic testing for a familial disorder. J Med Genet. 2006;43:665–70.

Marks D, Thorogood M, Neil SM, Humphries SE, Neil HA. Cascade screening for familial hypercholesterolaemia: implications of a pilot study for national screening programmes. J Med Screen. 2006;13:156–9.

Sermijn E, Goelen G, Teugels E, Kaufman L, Bonduelle M, Neyns B, et al. The impact of proband mediated information dissemination in families with a BRCA1/2 gene mutation. J Med Genet. 2004;41:e23.

Sturm AC. The role of genetic counselors for patients with familial hypercholesterolemia. Curr Genet Med Rep. 2014;2:68–74.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health through Grant KL2TR002490 to MCR. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official position of the National Institutes of Health or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Srinivasan, S., Won, N.Y., Dotson, W.D. et al. Barriers and facilitators for cascade testing in genetic conditions: a systematic review. Eur J Hum Genet 28, 1631–1644 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-020-00725-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-020-00725-5

This article is cited by

-

Strategies to improve implementation of cascade testing in hereditary cancer syndromes: a systematic review

npj Genomic Medicine (2024)

-

Direct notification by health professionals of relatives at-risk of genetic conditions (with patient consent): views of the Australian public

European Journal of Human Genetics (2024)

-

Patients’ perceptions and practices of informing relatives: a qualitative study within a randomised trial on healthcare-assisted risk disclosure

European Journal of Human Genetics (2024)

-

Cascade genetic counseling and testing in hereditary syndromes: inherited cardiovascular disease as a model: a narrative review

Familial Cancer (2024)

-

Challenges and opportunities for Lynch syndrome cascade testing in the United States

Familial Cancer (2024)