Abstract

Newborn screening (NBS) is an important part of public healthcare systems in many countries. The provision of information to parents about NBS is now recognised as an integral part of the screening process. Informing parents on all aspects of screening helps to achieve the benefits, promote trust and foster support for NBS. Therefore, policies and guidelines should exist to govern how the information about NBS is provided to parents, taking into account evidence-based best practices. The purpose of our survey was to explore whether any legally binding provisions, guidelines or recommendations existed pertaining to the provision of information about NBS to parents across Europe. Questions were designed to determine the regulatory process of when, by whom and how parents should be informed about screening. Twenty-seven countries participated in the survey. The results indicated that most countries had some sort of legal framework or guidelines for the provision of information to parents. However, only 37% indicated that the provision of information was required prenatally. The majority of countries were verbally informing parents with the aid of written materials postnatally, just prior to sample collection. Information was provided by a neonatologist, midwife or nurse. A website dedicated to NBS was available for 67% of countries and 89% had written materials about NBS for parents. The survey showed that there is a lack of harmonisation among European countries in the provision of information about NBS and emphasised the need for more comprehensive guidelines at the European level.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Newborn screening (NBS) for selected endocrine, metabolic and genetic disorders has been part of public health systems for more than 50 years with all developed countries worldwide establishing their own programmes [1]. As the complexity and array of screened disorders has increased so has the need for adequate regulations for running and maintaining NBS programmes. Like any complex organisation with many stakeholders, NBS programmes should have a defined structural organisation or policy framework with appropriate guidelines or recommendations to ensure their effective operation to the highest quality standards. Providing information and creating advocacy for NBS have been identified as key areas in the implementation of successful NBS programmes [2]. In order to facilitate informed participation, prospective parents need to be informed about the benefits and goals of NBS as well as the potential harms. Conveying information promotes a sense of trust, fosters support for the programme and may also ensure a prompt response to abnormal results by parents [3,4,5,6,7,8]. In contrast, when parents do not feel adequately informed this may lead to a lack of trust in NBS and the healthcare system in general [9], as was also seen in discussions around the storage and use of residual dried blood spots [10]. Moreover, refusal of NBS may lead to missed diagnosis as reported elsewhere [11].

Empirical studies from various countries have demonstrated there was a low level of awareness of NBS among parents, retention of the information may have been lacking or non-existent and parents often did not understand the principles of screening [12,13,14,15,16]. NBS was viewed as a routine procedure encompassed in standard postnatal care with little time allocated for informing parents. These studies from countries with different programme organisational structures revealed the similar results, mainly that parents were not receiving adequate information about NBS at the appropriate time during pregnancy [7, 9].

To ensure that parents are adequately informed, several countries have established policies for their NBS programmes on the provision of pre-test information to prospective parents whilst recognising the importance of standardising NBS practices across different states or provinces. The USA implemented a process of providing harmonised NBS services across all states based on recommendations from the American Academy of Paediatrics—Task Force on NBS (2000) which included the provision of information to prospective parents. The task force recommended that prospective parents should receive information on NBS in the prenatal period preferably in the third trimester, and that pregnant women should be made aware of the process and benefits of NBS. Parents should then be reminded of the screening after delivery of the newborn using education materials and discussion with a healthcare professional as needed [17].

In Europe NBS screening programmes are diverse. A survey was conducted in 2010 to provide an overview of the current status of NBS programmes across Europe analysing data from 37 countries [18]. The survey focused on five different aspects of screening; (1) the legal basis and general provisions for screening, (2) information to the public and prospective parents, (3) blood sampling and informed consent, (4) laboratory testing and blood spot storage, (5) confirmatory testing, communication of test results and treatment [19]. There were no specific questions regarding the regulation of information provision. From the information gathered in this survey an expert opinion document was formulated by the European Union Network of Experts on Newborn Screening (EUNENBS) which consisted of a group of 70 members with expertise in various aspects of NBS. The document contained recommendations on best practices including several recommendations regarding the provision of information about NBS [20]. It was recommended that NBS programme management should be responsible for the organisation and provision of information about NBS to parents and should define the content of information materials and provide communication guidelines for the healthcare professionals informing parents. Similar to US guidelines, it is advised to inform parents during pregnancy or even pre-conceptually and again before sample collection as this is the most desirable time for parents to be educated on NBS leading to better information retention as evidenced from empirical research [9]. The persons responsible for communicating information to prospective parents should be clearly defined within the programme guidelines. This task could be delegated for example to midwives or obstetricians/gynaecologists. Institutions responsible for carrying out the screening should have NBS information available on their websites in appropriate languages [20].

The purpose of this survey was to obtain an accurate assessment of the provision of pre-test information to parents within European NBS programmes and to ascertain whether expert recommendations were being incorporated into the process of educating parents. The survey was conducted by the European Society of Human Genetics (ESHG)-EuroGentest Quality Sub-committee in collaboration with the International Society for Neonatal Screening (ISNS). Questions were aimed at finding if there were any legally binding provisions or guidelines that NBS programmes adhered to when disseminating information to parents. The survey evaluated whether the exact timing of information provision was specified, who was responsible for providing the information, how the information was provided and what topics were covered in the available information materials. It is anticipated that the findings from the survey may identify areas for improvement in the provision of information about NBS to parents across Europe.

Materials and method

Survey content was developed by the authors in cooperation with ISNS representatives and the ESHG-EuroGentest Sub-committee. The survey was available in the English language only. To ensure the clarity of the questions the contents of the survey were reviewed by individuals who were independent of the study design and had the relevant expertise in NBS programme organisation, paediatrics and survey research methods. In April 2018 questionnaires were distributed through a group email to the coordinators of NBS programmes in European countries using the ISNS database of contacts or alternatively the chairs of national genetic societies contacted by the ESHG Office were asked to identify the appropriate NBS contacts in their countries. It was preferred to have one representative from each country complete the questionnaire to avoid conflicting answers. A total of 44 countries were initially invited via email to participate in the survey.

A web based questionnaire was set up using Surveymonkey®. Participants also received a copy (pdf file) of the questionnaire by email and had the option of emailing responses if they chose to do so. The response rate was lower than anticipated and a more personalised approach involving searches of NBS programme representatives in non-responding countries and individually addressed emails was used to encourage more countries to reply. Reminder emails were sent and/or phone calls were conducted to set new deadlines. Responses were collected between April 2018 and August 2018. To ensure up-to-date information, some additional data were added to the tables and footnotes during the paper revision by co-authors in February 2020. As NBS programmes are under constant development, co-authors reviewed the data in the tables about information provision in their country and added changes to reflect the current situation in their NBS programmes.

The first part of the survey aimed to establish whether a legal or regulatory framework existed for NBS programmes and consisted of questions pertaining to the presence of: (1) a national body responsible for NBS and (2) legally binding provisions, guidelines or recommendations specifically governing NBS.

The second part of the survey concerned pre-test information for NBS. The questions were designed to collect data on when, by whom and how were parents informed and whether this process was regulated by any legal provisions or guidelines, i.e., whether the guidelines/legal provisions indicated at what stage should parents be informed, who should be responsible for informing parents, how the information is communicated and what topics are specifically contained in information materials. The seven topics selected were based on the US study of Fant et al. [21]. This included the benefits/risks of screening, how parents will be informed of screening results, the importance of responding to a positive result, how to respond to a positive result, possibilities of false positive results, sample storage and use of residual sample. Respondents were also asked about the existence of a web page dedicated to NBS and whether the same topics were covered on the page. A question was also included to ascertain if countries performed any checks to see if the information actually reached its target population, and if so what type of audit was used (population surveys, interviews with parents or healthcare professionals or other methods). Survey questions are shown in Supplementary 1.

Results

Countries

Of the 44 countries contacted completed responses were received from 27 countries (two responses were incomplete and were not included in the final analysis) yielding the overall response rate of 61%.

Regulatory framework

Data on the regulatory framework in the 27 countries revealed that in 23 countries there was a national body (e.g., ministry, institute or committee) responsible for the NBS programme (Table 1). A list of the national bodies provided by individual countries can be found in Supplementary 2.

Every country had either legally binding provisions and/or national guidelines/recommendations and/or regional guidelines/recommendations. (Table 1). The overlap of these elements in different countries is illustrated in Fig. 1.

The Venn diagram is shown to illustrate the possible combination of three types of regulatory frameworks and their overlap. A similar number of countries had legally binding provisions (n = 19) or national guidelines/recommendations (n = 20) with an overlap between the two groups of nine countries. A much smaller number of countries had regional guidelines/recommendations (n = 6). Three countries had all three types of regulation. Other possible overlaps of regulations are shown in the figure.

The responses to whether legal provisions or guidelines that specified who is responsible for providing pre-test information to parents, when it is provided and how it is communicated are displayed in Table 2. Four countries reported having no legal provisions or guidelines/recommendations for any of these elements.

Provision of prenatal information

Only ten countries (37%) indicated that provision of NBS information in the prenatal period was required (Table 1). The details on provision of information prenatally are shown in Table 3. The majority of these countries (n = 8) had the midwife as the person responsible for providing pre-test information although not exclusively. Several countries (n = 5) indicated that more than one healthcare professional was also tasked with providing the information. Most countries (n = 9) used written information to communicate pre-test information (Table 3). The responses to the timing of information provision are listed in Table 3. Provision of written information prenatally was obligatory for only four countries (15% of all responding countries) (Table 3).

Provision of information postnatally

At the time of the survey 23 countries indicated that provision of pre-test information in the postnatal period was required (Table 1). Two countries reported there was no requirement to provide information postnatally or prenatally (Table 1).

Analysis of the when, by whom, and how of postnatal provision of NBS information is presented in Table 4. The majority of countries (n = 19) responded that the neonatologist in the neonatal ward was responsible for providing NBS information postnatally. Similar to the prenatal situation several healthcare professionals were tasked with providing the information (Table 4). The vast majority of countries had oral communication with a healthcare professional together with written materials as the method of providing information.

The timing of information provision in almost half of the countries (n = 10) was before sampling (Table 4). It was found that overall 26 countries had at least 1 form of communication provision for NBS information postnatally regardless as to whether it was a requirement or not.

NBS written materials and web pages

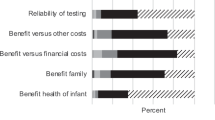

Written or electronic information materials for parents were available in 24 countries (Table 2). Two countries (Latvia and Slovenia) reported that written materials were in preparation at the time of the survey with Slovenia providing details of the topics to be included in the written materials. Only one country reported having neither resource for parents. A web page dedicated to NBS was available in 18 countries (Table 2). Links to NBS web pages are provided in Supplementary 2. Topics covered in both written materials and the web pages are illustrated in Fig. 2. Five countries covered all seven topics in their written materials and their internet pages. Coverage of topics ranged from 42 to 100% (Fig. 2).

For evaluation of information materials, the presented topics were selected based on recommendations from the American Academy of Paeditrics Task Force on NBS [25].

Twelve countries indicated that checks were performed to see if information reached its target audience (Table 2). Several countries mentioned their own unique methods of follow up checks including the “adequacy for each site between the number of leaflets/year and the number of newborns” (France), “Every year we do training of personnel concerning sampling and all information about the organisation of the National Program” (Portugal) and “We ask parents after referral of the child to the University Children’s Hospital (UCH), also about the level of information they already received” (Slovenia).

Discussion

This study is the first attempt to define how the provision of pre-test information to parents is regulated within NBS programmes across Europe. Encouragingly the majority of countries reported having a national body, legal provisions or guidelines/recommendations that specify who is responsible for providing pre-test information, when it should be communicated to parents and in what format the information should be provided. Every country reported having either legally binding provisions and/or national and/or regional guidelines and recommendations. Many countries had a different combination of these regulations. This might indicate both the importance of NBS programmes to national healthcare systems and demonstrate the ongoing commitment to providing a screening service of the highest standards. Nevertheless, results also revealed that there was a vast array of approaches towards the provision of pre-test information with little or no uniformity or standardisation between countries.

Only two countries specifically indicated they provide parents with information about NBS in the third trimester as recommended in European and international guidelines [17, 20]. The other eight countries that inform prenatally provide the information in various trimesters of pregnancy. Fourteen countries provide information only postnatally before sampling. This equates to informing parents at the last possible opportunity and at a time when new information about NBS cannot be assimilated [9, 18]. Some comparison of results on the timing of information provision can be made with the EUNENBS 2010 survey to evaluate NBS programmes in Europe. With the exception of Kazakhstan and the Ukraine all the respondents in our survey also participated in the 2010 survey. The similar results were found in 2010 when countries were informing parents at a variety of stages with approximately half informing after birth before sample collection [19]. Although we did not analyse how individual national or regional screening programmes implement the EUNENBS recommendations it appears from our survey results that there has not been much improvement in this aspect of information provision, partially due to lack of funding and discontinuation of the EUNENBS project.

Most countries had several options for who is responsible for providing information both prenatally and postnatally. It is evident that more guidance on who should provide the information is needed, whether this should be the role of the midwife or obstetrician prenatally or the neonatologist/midwife/nurse postnatally. The midwife would appear to be the most appropriate healthcare professional from the frequency of responses, however, maternity systems work differently for every country and for some the midwife may play a lesser role in the provision of prenatal care. For example in the Czech Republic midwives are not involved in informing parents about NBS [16]. In the UK the National Health Service specifically stipulates that the midwife provides NBS information at both the booking visit and in the third trimester with the aid of a leaflet [22]. The healthcare professionals involved in information provision about NBS should be adequately trained and provided with educational materials for parents [23]. NBS programmes should define these policies and assist in their implementation.

In our survey written information materials and oral communication by a healthcare provider appear to be the most common methods of disseminating NBS information to parents with 66% using both methods postnatally. Written information together with an explanation from a healthcare professional appears to be the most valued method of communication of pre-test information for parents [23]. However, only a small percentage of countries actually had a requirement for written information to be disseminated to parents either prenatally or postnatally (Tables 3 and 4).

When compared to the 2010 European NBS survey, there was a noticeable improvement in the number of countries with a website for NBS. In 2010 54% of countries reported having a website [19], whereas our survey found that 67% of countries had a website. Using multimedia tools and electronic platforms appears to be more useful for parents in understanding aspects of NBS [24]. It may be appropriate to consider new methods of communication such as applications for smartphones given their widespread use amongst the public.

For the evaluation of information materials, topics were selected based on recommendations from the American Academy of Paediatrics Task Force on NBS (2000) [25]. While certain topics were extensively covered by all countries, it was found that the storage and use of residual samples and the direct risks of screening were absent from ~50% of information materials. Similarities are seen between this survey and that of the Fant et al. study in the US examining the completeness and complexity of NBS information materials for parents in use by each state NBS programme [21]. Their study found that very few states at that time included information on storage and use of residual samples, however, the situation may have since improved. In the 2010 European NBS survey, consent for storage and use of dried blood spot samples after sampling was lacking in approximately two-thirds of countries [19]. No discernible improvement in this area can be identified from the results of our survey despite research showing that the public desire to be informed about sample storage and to be asked for consent for use of residual samples which consequently increases support for the NBS programmes [24, 26, 27]. Privacy concerns around the storage and use of blood spots have led to lawsuits in certain states in the USA and subsequent changes to legislation around parental consent [28]. It has also been a contentious issue in many other countries with rigorous debate around the lack of consent and sometimes public misperception around use of residual NBS cards resulting in legislation changes and in some cases destruction of NBS sample archives [10]. In the Republic of Ireland debate around the destruction of the NBS sample archive is still ongoing following a complaint made by a member of the public in 2009 regarding the retention of NBS samples without consent [29]. It would be prudent to encourage all European countries to include information on this subject in the relevant NBS information materials and possibly engage parent representatives in decision-making on the secondary use of residual blood spots [7]. This may be a more appropriate approach given the complex issues arising from this particular topic.

Individual European countries may have developed policies and guidelines on the provision of information to parents that already adheres to evidence-based best practices and European/international guidelines. Other European countries that may lack such guidelines could benefit from accessing these established procedures. For example, Australia and Canada have acknowledged the need to harmonise screening programmes between states or provinces and the benefits of sharing existing state policies. In Australia a national policy framework document on NBS produced in 2018 encourages states to collaborate in order to standardise the information being provided to parents on a national level [30]. In Canada the need to standardise NBS programmes across the country has been recognised including the modernisation of policies on information provision and the benefits of transferring policies or infrastructures developed in one province to another [31].

Limitations of the study

This study examined the regulatory environment regarding NBS information provision to parents but did not audit the actual practice of recording consent, storage nor secondary use of residual NBS samples. Another limitation in our study includes the potential for non-responders bias. Questions that were not answered may have influenced the overall result either positively or negatively. Another limitation is the lower response rate than that of the survey carried out in 2010. Only 27 countries participated in our survey as opposed to the 37 that responded in 2010. Two of the 27 countries from this survey did not participate in the 2010 questionnaire. There is also the possibility of ambiguous interpretation of questions. It is also noteworthy that the persons responding to this questionnaire were healthcare providers in the role of laboratory managers/directors, programme coordinators/leads, heads of departments, chairmen of NBS groups, or similar functions. They were not legal experts with in-depth knowledge of the law and may not have been aware of the exact legislation pertaining to the NBS process. This may have contributed to answers of “I don’t know” or “uncertain”. Regardless of these limitations our study provides an interesting insight into parental information provision about NBS in many European countries.

Conclusions

There are some promising results from this survey such as the fact that most countries have guidelines/recommendations or legal provisions stipulating when, by whom and how information about NBS should be provided. The vast majority of countries have written materials available for parents. While not every country has a website dedicated to their NBS programmes the majority do. However, there is insufficient standardisation of the information provision process and the need for harmonisation among European countries is evident. Countries are continuing to neglect to inform parents about NBS prenatally and there is little consensus between countries as to the exact time to provide information pre- and postnatally. This is despite international recommendations and numerous studies all indicating parents’ desire to be informed about NBS prenatally to allow them to be fully aware, to consent to NBS, and to lessen distress in the event of a positive result [3,4,5,6, 32, 33]. Harmonisation might help to take into consideration best practices developed in some screening programmes and to consider the evidence from empirical studies to ensure improvement of information provision across Europe. It may also be important to consider the consequences of the possible incorporation of next generation sequencing technologies into publicly funded NBS programmes. The complexities of such technology would result in the need for new NBS models of educating parents and increased resources to enable this to occur [34]. Any future attempts to harmonise NBS programmes on a European level should include specific guidelines relating to the provision of information about NBS to assist in standardisation of the process whilst also taking into account differences between maternity care systems in European countries.

References

Martinez-Morillo E, Prieto Garcia B, Alvarez Menendez FV. Challenges for worldwide harmonization of newborn screening programs. Clin Chem. 2016;62:689–98.

Therrell BL Jr., Padilla CD. Barriers to implementing sustainable national newborn screening in developing health systems. Int J Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2014;1:49–60.

Hewlett J, Waisbren SE. A review of the psychosocial effects of false-positive results on parents and current communication practices in newborn screening. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2006;29:677–82.

Kemper AR, Fant KE, Clark SJ. Informing parents about newborn screening. Public Health Nurs. 2005;22:332–8.

Gurian EA, Kinnamon DD, Henry JJ, Waisbren SE. Expanded newborn screening for biochemical disorders: the effect of a false-positive result. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1915–21.

Clayton EW. Talking with parents before newborn screening. J Pediatr. 2005;147:S26–9.

Jansen ME, van den Bosch LJM, Hendriks MJ, Scheffer MMJ, Heijnen ML, Douglas CMW, et al. Parental perspectives on retention and secondary use of neonatal dried bloodspots: a Dutch mixed methods study. BMC Pediatr. 2019;19:230.

Liebl B, Nennstiel-Ratzel U, von Kries R, Fingerhut R, Olgemoller B, Zapf A, et al. Expanded newborn screening in Bavaria: tracking to achieve requested repeat testing. Prev Med. 2002;34:132–7.

Ulph F, Wright S, Dharni N, Payne K, Bennett R, Roberts S, et al. Provision of information about newborn screening antenatally: a sequential exploratory mixed-methods project. Health Technol Assess. 2017;21:1–240.

Cunningham S, O’Doherty KC, Senecal K, Secko D, Avard D. Public concerns regarding the storage and secondary uses of residual newborn bloodspots: an analysis of print media, legal cases, and public engagement activities. J Community Genet. 2015;6:117–28.

Streetly A, Sisodia R, Dick M, Latinovic R, Hounsell K, Dormandy E. Evaluation of newborn sickle cell screening programme in England: 2010-2016. Arch Dis Child. 2018;103:648–53.

Araia MH, Wilson BJ, Chakraborty P, Gall K, Honeywell C, Milburn J, et al. Factors associated with knowledge of and satisfaction with newborn screening education: a survey of mothers. Genet Med. 2012;14:963–70.

Suriadi C, Jovanovska M, Quinlivan JA. Factors affecting mothers’ knowledge of genetic screening. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;44:30–4.

Nicholls SG, Southern KW. Parental information use in the context of newborn bloodspot screening. An exploratory mixed methods study. J Community Genet. 2012;3:251–7.

Al-Sulaiman A, Kondkar AA, Saeedi MY, Saadallah A, Al-Odaib A, Abu-Amero KK. Assessment of the knowledge and attitudes of Saudi mothers towards newborn screening. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:718674.

Frankova V, Dohnalova A, Peskova K, Hermankova R, O’Driscoll R, Jesina P, et al. Factors influencing parental awareness about newborn screening. Int J Neonat Screen. 2019;5. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns5030035.

American Academy of Pediatrics. Newborn screening: a blueprint for the future executive summary: newborn screening task force reporg. Pediatrics. 2000;106:386–8.

Loeber JG, Burgard P, Cornel MC, Rigter T, Weinreich SS, Rupp K, et al. Newborn screening programmes in Europe; arguments and efforts regarding harmonization. Part 1. from blood spot to screening result. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2012;35:603–11.

Burgard P, Cornel M, Di Filippo F, Haege G, Hoffmann GF, Lindner M, et al. Report on the practices of newborn screening for rare disorders implemented in member states of the European Union, candidate, potential candidate and EFTA countries. 2012. http://old.iss.it/binary/cnmr/cont/Report_NBS_Current_Practices_20120108_FINAL.pdf. Accessed 17 Sept 2019.

Cornel MC, Rigter T, Weinreich SS, Burgard P, Hoffmann GF, Lindner M, et al. A framework to start the debate on neonatal screening policies in the EU: an expert opinion document. Eur J Hum Genet. 2014;22:12–7.

Fant KE, Clark SJ, Kemper AR. Completeness and complexity of information available to parents from newborn-screening programs. Pediatrics 2005;115:1268–72.

NHS public health functions agreement 2018-19, service specification no.19, NHS newborn blood spot screening programme. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Gateway-ref-07840-180913-Service-specification-No.-19-NHS-Newborn-Blood-Spot-Screening.pdf. Accessed 15 Oct 2019.

Davis TC, Humiston SG, Arnold CL, Bocchini JA Jr., Bass PF 3rd, Kennen EM, et al. Recommendations for effective newborn screening communication: results of focus groups with parents, providers, and experts. Pediatrics. 2006;117:S326–40.

Botkin JR, Rothwell E, Anderson RA, Rose NC, Dolan SM, Kuppermann M, et al. Prenatal education of parents about newborn screening and residual dried blood spots: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170:543–9.

Serving the family from birth to the medical home. A report from the newborn screening task force convened in Washington DC, May 10-11, 1999. Pediatrics. 2000;106:383–427.

Botkin JR, Rothwell E, Anderson R, Stark L, Goldenberg A, Lewis M, et al. Public attitudes regarding the use of residual newborn screening specimens for research. Pediatrics. 2012;129:231–8.

Charles T, Pitt J, Halliday J, Amor DJ. Implementation of written consent for newborn screening in Victoria, Australia. J Paediatr Child Health. 2014;50:399–404.

Caggana M, Jones EA, Shahied SI, Tanksley S, Hermerath CA, Lubin IM. Newborn screening: from Guthrie to whole genome sequencing. Public Health Rep. 2013;128:14–9.

Hanafin S. Report on the newborn screening card archive forum. Ireland: Department of Health; 2017. p. 1–35. https://assets.gov.ie/41907/635daa08fe744854b1feb6f85d44f0c6.pdf. Accessed 09 Dec 2019.

Australian Health Minsters’ Advisory Council. Newborn Bloodspot Screening, National Policy Framework. http://www.cancerscreening.gov.au/internet/screening/publishing.nsf/Content/newborn-bloodspot-screening. Accessed 6 Oct 2019.

Wilson K, Kennedy SJ, Potter BK. Developing a national newborn screening strategy for Canada. Health Law Rev. 2010;18:31–9.

Etchegary H, Nicholls SG, Tessier L, Simmonds C, Potter BK, Brehaut JC, et al. Consent for newborn screening: parents’ and health-care professionals’ experiences of consent in practice. Eur J Hum Genet. 2016;24:1530–4.

Detmar S, Hosli E, Dijkstra N, Nijsingh N, Rijnders M, Verweij M. Information and informed consent for neonatal screening: opinions and preferences of parents. Birth. 2007;34:238–44.

Howard HC, Knoppers BM, Cornel MC, Wright Clayton E, Senecal K, Borry P, et al. Whole-genome sequencing in newborn screening? A statement on the continued importance of targeted approaches in newborn screening programmes. Eur J Hum Genet. 2015;23:1593–600.

Funding

Institutional support was provided by projects LM2018132 from the Large Infrastructure Projects of the Czech Ministry of Education, PROGRES Q26 from Charles University and RVO VFN 64165 from the Ministry of Health, Czech Republic. Several authors of this publication are members of the European Reference Network for Rare Hereditary Metabolic Disorders (MetabERN)—Project ID No. 739543.

Members of the European Society of Human Genetics (ESHG)-EuroGentest Quality Sub-CommitteeZandra C. Deans31, Christi J. van Asperen32 Mick J. Henderson33, David Barton34, Elisabeth M. C. Dequeker35,36, Isabel Marques Carreira37, Thomy de Ravel38, Katrina Rack39, Katrin Õunap40

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Franková, V., Driscoll, R.O., Jansen, M.E. et al. Regulatory landscape of providing information on newborn screening to parents across Europe. Eur J Hum Genet 29, 67–78 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-020-00716-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-020-00716-6

This article is cited by

-

Identification of maternal attitudes and knowledge about newborn screenings: a Turkey sample

Journal of Community Genetics (2023)