Abstract

Genetics in paediatric oncology is becoming increasingly important in diagnostics, treatment and follow-up care. Genetic testing may offer a possibility to stratify survivors follow-up care. However, survivors’ and parents’ preferences and needs for genetics-related services are largely unknown. This mixed-methods study assessed genetics-related information and service needs of survivors and parents. Six hundred and twenty-two participants (404 survivors: mean age: 26.27 years; 218 parents of survivors: mean age of child: 13.05 years) completed questionnaires. Eighty-seven participants (52 survivors; 35 parents) also completed in-depth telephone interviews. We analysed data using multivariable logistic regression and qualitative thematic analyses. Thirty-six of 50 families who were offered cancer-related genetic testing chose to undergo testing. Of those not offered testing, 11% of survivors and 7.6% of parents indicated that they believed it was ‘likely/very likely’ that the survivor had inherited a gene fault. Twenty-nine percent of survivors and 36% of parents endorsed access to a genetics specialist as important in their care. Survivors (40.9%) and parents (43.7%) indicated an unmet need for information about genetics and childhood cancer. Parents indicated a higher unmet need for information related to the survivors’ future offspring than survivors (p < 0.001). Many survivors and parents have unmet needs for genetics-related services and information. Greater access to services and information might allow survivors at high risk for late effects to detect and prevent side effects early and improve medical outcomes. Addressing families’ needs and preferences during survivorship may increase satisfaction with survivorship care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Survival rates for childhood cancers have drastically improved over the last few decades with around 80% surviving their cancer for more than 5 years [1, 2]. Despite this success, >60% of childhood cancer survivors suffer from at least one chronic health condition due to treatment-related toxicity and side effects [3]. Continued follow-up care with appropriate access to services is therefore essential [4, 5]. Follow-up care can help to prevent treatment-related health conditions, manage existing health conditions, and provide support and information as needed [6, 7].

Recently, genetic/genomic testing has been identified as a potential additional tool in childhood cancer survivorship care [8, 9]. Survivors’ follow-up care can be stratified according to their risk of developing late effects, usually determined by their cancer type and treatment received [10, 11]. Genetic/genomic testing may offer a possibility to stratify childhood cancer survivors’ follow-up care by their risk of recurrence, second cancers and other physical complications [7, 9, 12]. Recent research indicates that 10–15% of all childhood cancers are caused by cancer predisposition genes [13]. These increase the risk for subsequent cancers [9] and potentially affect offspring and other family members [8]. Thirty percent of childhood cancer survivors may require a genetics risk assessment, either because they were diagnosed prior to the genetics revolution or because of evolving family history [14]. Survivors with multiple primary tumours and survivors with family members with previous childhood cancers should in particular be offered access to genetic services [8]. Some researchers have argued that all childhood cancer survivors should be referred to genetics services, with priority given to survivors with a secondary neoplasm, who did not receive radiotherapy, and to survivors with breast cancer/sarcoma in the field of prior radiotherapy treatment [9]. Genetic assessment may reveal risks for survivors’ family members and (future) offspring [8]. If a variant associated with cancer predisposition is identified, genetic services provide support for at-risk family members, provide genetic counselling and help with reproductive decisions. Further, when a variant associated with cancer predisposition is identified in a survivor, knowing the cause of the cancer can provide solace and possibly shape personal health beliefs [15]. For those identified as low risk, reassurance for the survivor and family members can also be helpful [14].

Before establishing new services, it is important to assess consumers’ thoughts, preferences and (information) needs. Over 20 years ago, a study reported that mothers of childhood cancer patients were hypothetically willing to uptake genetic testing, without even evidence of clear medical benefit [16]. A study of childhood cancer survivors also showed that survivors are interested identifying their risk of developing late effects through genetics [17]. Survivors were willing to pay for testing and to wait up to 6 months to receive the results [17]. The perceived benefits of testing outweighed their concerns [17]. Despite increasing recognition of the potential role of genetics assessment in childhood cancer survivorship [14], there has not been a comprehensive examination of childhood cancer survivors’ and parents’ genetics service preferences and information needs. The relationship between these needs, their satisfaction with care and their psychological well-being is also unknown. By more clearly understanding families’ genetics-related information and service needs, healthcare professionals can better meet these needs and make appropriate referrals, potentially increasing satisfaction with care.

This mixed-method study therefore assessed childhood cancer survivors’ and parents’:

- 1.

Genetics-related service use and desire for future genetics specialist consultation.

- 2.

Perceived importance of receiving genetics-related information, their unmet genetics-related information needs and their preferred modes of information delivery.

- 3.

Beliefs and concerns about childhood cancer genetics.

We addressed these aims first for families in which the child’s cancer was confirmed or suspected to be related to a genetic condition (‘families with possible genetic condition’) and then in families without a suspected genetic condition (‘families without suspected genetic condition’). We also aimed to identify demographic and clinical predictors of genetics service needs and unmet information needs, in order to identify families appropriate for targeted education/counselling.

Methods

We used a mixed-method approach. In stage 1, we sent questionnaires to survivors and survivors’ parents. In stage 2, we invited participants who opted in at stage 1 to an in-depth telephone interview [18, 19].

Participants

We invited a random selection of survivors who were treated at the Australian and New Zealand children’s hospitals, who were <16 years at diagnosis, ≥5 years post diagnosis, had completed active treatment, were alive and in remission, and were proficient in English. We invited the survivor directly if they were aged >16 years and we invited survivors’ parents if the survivor was aged <16 years. Only one questionnaire was collected per family.

Procedure

An expert committee helped design the questionnaire, which we then piloted with five survivors and five parents. We piloted the interviews with two survivors and two parents. The study was approved by the ethics authority at each participating site and endorsed by the Australian and New Zealand Children’s Haematology Oncology Group. The lead clinician at each site posted the study documents to participants, which included an invitation letter, a consent form, questionnaire and a pre-paid envelope. We followed-up with non-respondents after 4 weeks. Experienced psychosocial researchers conducted the telephone interviews.

Measures

Socio-demographics

We assessed the survivor’s age and the participants’ sex, education level and household income (Table 1).

Medical characteristics

We assessed survivors’ first cancer diagnosis, time since first cancer diagnosis, time since last follow-up and whether their cancer had relapsed.

Worry about cancer recurrence/ late effects

We assessed participants’ worry about the cancer returning and about developing late effects on a five-point Likert scale (response options: ‘not at all’ to ‘a great deal’).

Quality of life (QoL)

We assessed quality of life (QoL) with the EQ-5D-5L, a six-item standardized measure comprising five items: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety and depression [20]. Responses ranged from ‘no problem’ to ‘extreme problem’. The sixth item assesses self-rated health today with a visual analogue scale (0 = ‘Worst health you can imagine’, to 100 = ‘Best health you can imagine’). For each participant, we calculated a QoL index value, using the five domains and Model D of the Australian sample value set [21, 22].

Global satisfaction with care

Based on previous studies [23, 24], we assessed global satisfaction with one item asking about the participant’s level of satisfaction with the survivor’s cancer-related follow-up care (1 = ‘very unsatisfied’ to 5 = ‘very satisfied’). We categorized this variable into the following: unsatisfied (i.e., ‘very unsatisfied’/‘unsatisfied’), ‘neither’ and ‘satisfied’ (i.e., ‘satisfied’/‘very satisfied’).

Beliefs about cancer genetics

We asked participants about their beliefs about the causes of childhood cancer [15]. For this paper we only reported beliefs about genetics playing a role (i.e., ‘it runs in family’).

Beliefs about carrying a gene fault

We asked participants to estimate the likelihood that the survivor carries a gene fault that caused the cancer, and that the survivors’ future children may carry the same gene fault (five-point scale: ‘Very unlikely’ to ‘Very likely’).

Perceived importance of receiving genetics-related information

We assessed this using one item with response options: 1 = ‘Not important’, 2 = ’Important’, 3 = ‘Very important’.

Genetics-related information needs

We assessed genetics-related information needs using one overarching item, asking whether participants had a need for ‘Genetic information related to my (child’s) cancer’, and two sub-items, asking about their information need about any risks to other family members and any risks to the survivors’ future children (response options: 1 = ‘not needed’, 2 = ‘needed but not received’, 3 = ‘needed and received some’, 4 = ‘needed and received enough’). We based the item design on a validated information needs tool for cancer survivors [25]. We listed questions about genetics information needs among a list of other information needs to reduce the focus on genetics. The items demonstrated good internal consistency in survivors (α = 0.88) and parents (α = 0.87). We dichotomized the items to indicate ‘(un)met needs’ (2 and 3 = ‘need unmet’; 1 and 4 = ‘need met’).

Importance of access to a geneticist/genetic counsellor

We asked, ‘Which health professionals do you think are important to have access to at a long-term follow-up clinic?’ To reduce the focus on genetics, we listed genetic specialists among 16 other healthcare professionals.

Genetics-related service use was assessed by asking whether the survivor had seen a genetic counsellor/geneticist since the cancer diagnosis and how often.

We addressed the following topics in the interviews (Appendix):

- 1.

Concerns (if any) regarding cancer risk in family members,

- 2.

Understanding of the role of genetics in childhood cancer and survivorship care,

- 3.

Desire for, or intentions to undergo, genetic counselling/testing,

- 4.

Desire for genetics-related information,

- 5.

Preferred delivery mechanism for genetics information.

Statistical analysis

We performed all analyses using StataSE 15, College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC. We summarized the data using descriptive statistics. We analysed descriptive data separately for participants who indicated a suspected genetic condition in their family. For the regression analysis we dichotomized the variables into one information needs variable (0 = no needs at all, 1 = needs on at least one of the genetics-related information needs items). We conducted univariable and multivariable logistic regressions to examine the associations between outcomes and demographic and clinical variables separately for survivors and survivors’ parents. We used Pseudo R2 to report the amount of variance in the outcome accounted for by the predictors in the final model (Tables 2 and 3). Regression analyses excluded those who had a suspected genetic condition.

We recorded all interviews and transcribed them verbatim. We analysed interview data using thematic analysis to enable the organization of responses into themes, supplemented with the methodology described by Miles and Huberman [26]. The coding structure was informed by the structured interview questions (Appendix). We coded responses line by line using NVivo11. We extracted illustrative quotes to inform our quantitative findings from the questionnaire. We used matrix coding to cross-analyse themes and participant characteristics (e.g., separating survivors and parents). Two coders (LF and JV) double coded 20% of interviews (99.2% agreement).

Results

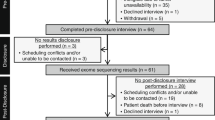

In total, 622 participants responded to our questionnaire (response rate 53.8%). Survivors who did not respond differed significantly from respondents in sex and age (χ2 = 15.36, p < 0.001, t = −5.83, p < 0.001). Non-respondents were younger (23.3 years) and more often male than respondents (55.8% male vs. 43.3% male). Of the 622 participants, 361 opted in to the interview, of which 87 eligible and reachable participants (52 survivors, 35 parents) completed the in-depth interview when we reached saturation. Of those 87, 12 had been offered genetic testing and 7 had consented to undergo genetic testing.

In total, 404 survivors (mean age: 26.27 years, SD = 7.6) and 218 parents (child mean age: 13.05 years, SD = 2.5) participated. Fifty families (8.0%) had been offered cancer-related genetic testing (Tables 1 and 2), 36 (72.0%) of whom had chosen to undergo testing (14 survivors: mean age: 24.6 years, SD = 9.5; 22 parents: child mean age: 12.5 years, SD = 2.7). Twenty-seven (4.3%) reported that the survivors’ cancer was related to a (known) genetic predisposition syndrome. Not all stated what the predisposition was. Examples given were breast cancer (n = 1), Neurofibromatosis 1 (n = 4), Fanconi’s anaemia (n = 1), Down syndrome (n = 3), Gorlin syndrome (n = 2), Retinoblastoma (n = 1), autism (n = 1) and Beckwith–Wiedermann syndrome (n = 1).

Genetics-related service use and desire for future consultation

Families with possible genetic condition

Of the 27 participants who were told that the survivors’ cancer was related to a genetic condition, 5 out of 13 survivors (38.5%) and 3 out of 14 parents (21.4%) had consulted a geneticist or genetics specialist. Five out of 13 survivors (38.5%) and 7 out of 14 parents (50.0%) indicated that it was important to have access to a genetics specialist as part of their care. One mother explained that they received a lot of cancer-related genetics information and would always be able to talk to the genetic services if needed: “They did give us a lot of information. [The] clinic is there for those boys whenever they need it, to be able to go and talk and have genetic counselling and talk about it whenever they need to, about what the implications would be.” (Mother, 15 y.o. survivor).

Most participants who reported a possible genetic condition perceived that learning genetics-related information (survivors (11/13): 84.6%; parents (12/14): 85.7%) was ‘important’/‘very important’ in survivorship care. However, these needs remained unmet in 69% of survivors (9/13) and 31% parents (4/9; p = 0.050). Survivors (61.5%; 8/15) and parents (28.6%; 4/14) indicated an unmet information need about the cancer genetic risk for other family members. Survivors (46.2%; 6/13) and parents (35.7%; 5/14) indicated an information need related to the survivor having their own children.

Families without suspected genetic condition

Six survivors (out of 377; 1.6%) and six parents (out of 201; 3.0%) of families had consulted a geneticist/genetics specialist regarding the cancer despite not indicating that the survivors’ cancer was related to an inherited condition. Yet, 28.8% survivors (n = 110/382) and 35.5% parents (n = 72/203) reported that access to a genetics specialist was important. This was confirmed by interviewees, with survivors and parents describing the importance of having access to a genetic expert to ask questions when they arose. “I definitely feel it is part of it, genetics. I can’t imagine it not being part of it.” (24 y.o. female survivor). Several survivors highlighted the importance of talking to genetics experts who were able to explain complex concepts in an understandable way. “If I can associate with [genetics experts]…. On a similar level in conversation for sure.” (25 y.o. male survivor).

For survivors, longer time since diagnosis (odds raio (OR) = 1.09, p = 0.002; Table 2) and younger age at study (p = 0.031) was associated with a greater likelihood of indicating that access to a genetic counsellor/geneticist was important. None of the tested factors was associated with parents’ ratings of importance of access to genetic counsellor/geneticists.

Most participants without a suspected genetic condition reported that receiving genetics-related information (survivors: 299/373, 80.2%; parents: 169/201, 82%) was ‘important’/‘very important’ in survivorship care. However, although many participants reported genetics information needs since the survivor’s diagnosis, these needs remained unmet in 40.9% of survivors (152/372) and 43.7% of parents (87/199; Fig. 1). Survivors (38.0%; 141/371) and parents (40.7%; 81/199) indicated an unmet information need about the cancer genetic risk for other family members, and 32.1% survivors (119/371) and 53.3% parents (106/199; p < 0.001) indicated an unmet information need related to survivors having children (Fig. 1). This finding was echoed in interviews, where participants highlighted a specific information need about cancer risk for future offspring: “In the future I mightn’t have children but if I ever did, I would like to know whether it’s a trait that I could pass on and whether there’s some way of getting around it.” (37 y.o. male survivor) One mother was unsure whether her child’s cancer was heritable: “….[I don’t know] if potentially future generations can have - like if my grandchildren are going to have yolk sac tumours.” (Mother, 11 y.o. survivor). Even though most participants expressed an interest in genetic information, some were less interested if it was not specific to their condition: “I’m not sure what I would do with that information at this point in time. If it was relevant to neuroblastoma, yes. But in regard to just general genetics and cancer, I’m not keen. No. It’s not something I think I would open and read.” (Mother, 13 y.o. survivor).

Although many interviewees described a strong desire for genetics-related information, most had not sought the information themselves. Some families, however, had searched their family history and the internet. Interviewees described the value of a potential explanation for their (child’s) cancer and risk for future offspring: “Just to put some sort of justification to everything you go through…I am getting to the stage where I’m talking about how it will long-term affect me.” (17 y.o. female survivor).

Survivors who made a genetic attribution were more likely to indicate that they had an unmet information need (OR = 1.93, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.01–3.67; Table 3). Survivors without a post-school qualification (p = 0.015) and survivors dissatisfied with their follow-up care (p = 0.028) were more likely to indicate an unmet information need compared with those who had post-school qualification and those who were satisfied (Table 3). Parents who made a genetic attribution were more likely to indicate an unmet information need (OR = 2.81, 95% CI: 1.05–7.51). Parents who indicated they were neither satisfied/dissatisfied or satisfied with their child’s follow-up care were more likely to indicate an unmet information need related to their child’s cancer than those not satisfied (OR = 42.64, 95% CI: 3.53–514.90 and OR = 4.09, 95% CI: 1.15–14.57, respectively; Table 3).

Interviewees described a strong preference for written materials about genetic aspects of childhood cancer (either paper-based, online or both). Fewer expressed an interest in attending a face-to-face educational seminar/workshop, although some participants indicated interest, “if it was not too far from home”.

Beliefs and concerns about childhood cancer-related genetics

Sixty-eight survivors of 371 (18.3%) and 43 parents of 198 (21.7%) patients who did not indicate that their cancer was related to a genetic condition endorsed ‘genetics (‘it runs in the family’) as a cause of the survivors’ cancer. As one survivor explained: “My uncle had the same cancer as me…I always think it runs in families.” (24 y.o. female survivor). Mirroring the quantitative results, most participants did not believe that genetics played a role, as one mother said: “Don’t think [genetics played a role] because there’s no history of cancer in my family” (22 y.o. male survivor)

Another survivor explained that her family history evolved over time, which made her think about genetics later after diagnosis and treatment: “I was the first one in the family to be sick. So, I never really thought about genetics, but then once my younger brother got sick and then my mother, it was like, is this just crappy genetics?” (25 y.o. female survivor).

Forty-two survivors (of 378; 11.1%) and 15 parents (of 197; 7.6%) indicated that they believed it was ‘likely’/‘very likely’ that the survivor had inherited a gene fault that caused the cancer. Despite not having been identified as a family with a suspected heritable condition, 29 survivors (of 372; 7.8%) and 9 (of 196; 4.6%) parents indicated it was ‘likely’/very likely’ that this gene fault would be transmitted.

Although many interviewees reported that they did not worry about their parents and siblings developing cancer, others described strong concerns for other family members. Even in interviewees who did not attribute their cancer to an inherited condition, many survivors remained concerned about the cancer risk in their offspring. “That is one of my main concerns, that my kids would have cancer, or have childhood cancer, or have a higher risk of it. It does make having biological children a nasty concept. I could adopt and get somebody else’s probability rather than my own.” (28 y.o. female survivor).

Although many interviewees demonstrated a good understanding of the difference between an inherited condition and a sporadic genetic change causing cancer, several interviewees demonstrated misunderstandings about the cause of cancer and the role of genetics.

As one survivor explained: “It is a genetic condition. Something amiss with your DNA… In terms of the inheritance question, there has been young deaths from cancer in my family… but not Wilms’ tumour.” (28 y.o. female survivor). A mother suggested her parents’ use of chemicals as a possible explanation: “My father died of cancer, [my husband’s] father died of cancer, but they were both great ones to play with chemicals. Whether that caused damage to my DNA and my husband’s DNA, who knows.” (Mother, 13 y.o. female).

Discussion

Although only a small proportion of participants indicated an underlying cancer predisposition syndrome, unmet cancer-related genetics information needs and access to genetic services were prevalent among survivors and survivors’ parents. Survivors’ need for access to genetics services was greater with longer time since diagnosis and younger age at study. Unsurprisingly, the need for cancer-related genetics information was greater among survivors and survivors’ parents who attributed genetics as a cause of cancer. Survivors who were dissatisfied and parents who were neither satisfied/dissatisfied or satisfied with their cancer-related follow-up care had greater unmet genetic information needs.

Given estimates that <3% of published genetics research focuses on the application of basic discoveries into health services [27], this study is urgently needed. This study investigates the genetics-related service and information needs of adult childhood cancer survivors (and younger survivors’ parents), as well as qualitatively examining the participants’ views about cancer-related genetics. The present findings demonstrate some misunderstanding around cancer genetics. A relatively large number of participants held beliefs that their cancer ‘runs in the family’ even though they indicated their cancer was not related to a genetic condition. Similarly, there were survivors and parents who believed it was likely a gene fault caused the cancer and it would be passed on to future offspring, despite not having a suspected cancer predisposition syndrome in the family. Offspring studies have shown that the risk of transmitting childhood cancer is low if the cancer is not caused by a cancer predisposition syndrome [28, 29]. Despite this low risk, another study found that fears about cancer in offspring prevented some survivors from having their own children [30]. This also mirrors the findings of previous studies on genetics-related misunderstandings of those affected by genetic diseases [31]. Together, these findings suggest that childhood survivors and parents need further educational support about cancer genetics.

Most families perceived genetics-related information was important for their survivorship care, but this information need often remained unmet. Many participants also indicated unmet information needs regarding genetic risks for family members and future offspring. In addition, participants expressed the importance of having access to a genetic specialist as part of their care, which may explain why most interviewees expressed a strong genetics-related information need yet had not sought such information themselves. Participants emphasized that genetics experts play an important role in answering questions and explaining complex concepts. Previous reviews have also demonstrated parents’ [32] and children’s [33] positive attitudes towards childhood genetic testing, yet hesitance over its limitations and possible risks [33]. Other studies suggested that genetic/genomic testing and information in children with cancer has minimal psychosocial implications [34, 35] but expectations and the potential burden need to be discussed [36].

Few clinical variables were associated with unmet genetics-related information needs and access to genetics services. The findings that, among survivors, longer time since diagnosis and younger age at study were associated with placing greater importance on access to genetic services are to be expected. The potential genetic implications of their cancer for others are likely to become more important to the survivor as the cancer itself becomes less threatening to them and they consider their reproductive options. Access to genetics-related services and information will be crucial and might provide peace of mind and increase satisfaction with care, especially for survivors who were dissatisfied with follow-up care and for families who attributed genetics as a cause of (their) cancer [37]. Interestingly, parents with greater satisfaction and neither satisfaction/dissatisfaction with follow-up care expressed greater need for genetics-related information, which might indicate that some parents might always require more information about their child’s health and remain concerned about their future health. Survivors and parents might become more concerned about offspring and family members, and therefore are increasingly eager for more information about potential (future) risk. Follow-up care might act as a gateway to access services such as genetic testing/counselling.

Strengths and limitations

A major strength of this study is the large and diverse sample including survivors whose cancer was related to a genetic condition and survivors where there was no genetic attribution, as well as survivors who regularly attend a follow-up care clinic along with those who do not. Another strength of this study is the use of a mixed-methods approach, which allowed for the measurement of a broad range of quantitative variables, as well as an in-depth qualitative exploration of survivors’ and parents’ preferences and information needs related to childhood cancer genetic services.

However, this study also needs to be considered in light of its limitations. Recall bias was likely associated with many of the participants’ responses. Given the long time since diagnosis, it is unclear whether survivors and parents recalled their medical condition, history of genetic testing, receipt of genetic information, and contact with genetic services correctly.

Cancer genetics-related information will become increasingly important as genetic/genomic testing is more widely implemented into clinical practice. Families’ needs will likely differ depending on the way they are identified for genetic evaluation. Little is known about families’ needs when they are identified through genetic testing/whole-genome sequencing at the time of the child’s diagnosis as part of research or as standard care. Genetics-related service and information needs will therefore likely need to be reassessed in future studies. Meeting the information needs of survivors and parents, and facilitating access to services might decrease some misunderstandings about cancer genetics [15]. With educational support, survivors and parents of survivors will be able to better plan for their future, potentially increase their satisfaction with (survivorship) care, and may improve survivors’ and their families’ QoL. Genetic specialists and counsellors will play a crucial role in counselling families before and after testing. Information should be disseminated and services adjusted to be age and developmentally appropriate for young children and adults considering and undergoing testing. Greater access to services and information might allow survivors at high risk for late effects to detect and prevent side effects early and improve medical outcomes. Addressing families’ needs and preferences during survivorship may increase satisfaction with survivorship care.

References

Gatta G, Botta L, Rossi S, Aareleid T, Bielska-Lasota M, Clavel J, et al. Childhood cancer survival in Europe 1999-2007: results of EUROCARE-5–a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:35–47.

Gatta G, Capocaccia R, Coleman MP, Ries LA, Berrino F. Childhood cancer survival in Europe and the United States. Cancer. 2002;95:1767–72.

Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, Kawashima T, Hudson MM, Meadows AT, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. New Engl J Med. 2006;355:1572–82.

Friedman DL, Freyer DR, Levitt GA. Models of care for survivors of childhood cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;46:159–68.

Tonorezos ES, Barnea D, Cohn RJ, Cypriano MS, Fresneau BC, Haupt R, et al. Models of care for survivors of childhood cancer from across the globe: advancing survivorship care in the next decade. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:2223–30.

Oeffinger KC, Nathan PC, Kremer LC. Challenges after curative treatment for childhood cancer and long-term follow up of survivors. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2010;24:129–49.

Armenian SH, Landier W, Hudson MM, Robison LL, Bhatia S. Children’s Oncology Group’s 2013 blueprint for research: survivorship and outcomes. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;60:1063-8.

Strong LC. Genetic implications for long-term survivors of childhood cancer. Cancer. 1993;71(10 Suppl):3435–40.

Wang Z, Wilson CL, Easton J, Thrasher A, Mulder H, Liu Q, et al. Genetic risk for subsequent neoplasms among long-term survivors of childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:2078–87.

Geenen MM, Cardous-Ubbink MC, Kremer LC, van den Bos C, van der Pal HJ, Heinen RC, et al. Medical assessment of adverse health outcomes in long-term survivors of childhood cancer. JAMA 2007;297:2705–15.

Frobisher C, Glaser A, Levitt GA, Cutter DJ, Winter DL, Lancashire ER, et al. Risk stratification of childhood cancer survivors necessary for evidence-based clinical long-term follow-up. Br J Cancer. 2017;117:1723–31.

Ripperger T, Bielack SS, Borkhardt A, Brecht IB, Burkhardt B, Calaminus G, et al. Childhood cancer predisposition syndromes-A concise review and recommendations by the Cancer Predisposition Working Group of the Society for Pediatric Oncology and Hematology. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2017;173:1017–37.

Grobner SN, Worst BC, Weischenfeldt J, Buchhalter I, Kleinheinz K, Rudneva VA, et al. The landscape of genomic alterations across childhood cancers. Nature. 2018;555:321–7.

Knapke S, Nagarajan R, Correll J, Kent D, Burns K. Hereditary cancer risk assessment in a pediatric oncology follow‐up clinic. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;58:85–9.

Vetsch J, Wakefield CE, Doolan EL, Signorelli C, McGill BM, Moore L, et al. ‘Why us?’ Causal attributions of childhood cancer survivors, survivors’ parents and community comparisons - a mixed methods analysis. Acta Oncol. 2019;58:209–17.

Patenaude AF, Basili L, Fairclough DL, Li FP. Attitudes of 47 mothers of pediatric oncology patients toward genetic testing for cancer predisposition. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:415–21.

Georgiou G, Wakefield CE, McGill BC, Fardell JE, Signorelli C, Hanlon L, et al. Genetic testing for the risk of developing late effects among survivors of childhood cancer: consumer understanding, acceptance, and willingness to pay. Cancer. 2016;122:2876–85.

Vetsch J, Fardell JE, Wakefield CE, Signorelli C, Michel G, McLoone JK, et al. “Forewarned and forearmed”: long-term childhood cancer survivors’ and parents’ information needs and implications for survivorship models of care. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100:355–63.

Signorelli C, Wakefield CE, McLoone JK, Fardell JE, Lawrence RA, Osborn M, et al. Models of childhood cancer survivorship care in Australia and New Zealand: Strengths and challenges. Asia -Pac J Clin Oncol. 2017;13:407–15.

Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, Janssen M, Kind P. Parkin D, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res. 2011;20:1727–36.

Norman R, Cronin P, Viney R. A pilot discrete choice experiment to explore preferences for EQ-5D-5L health states. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2013;11:287–98.

Rabin ROM, Oppe M. EQ-5D-5L User Guide (ed Version 1.0) Rotterdam; 2011.

Lee DS, Tu JV, Chong A, Alter DA. Patient satisfaction and its relationship with quality and outcomes of care after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2008;118:1938–45.

Coyte PC, Wright JG, Hawker GA, Bombardier C, Dittus RS, Paul JE, et al. Waiting times for knee-replacement surgery in the United States and Ontario. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1068–71.

Boyes A, Girgis A, Lecathelinais C. Brief assessment of adult cancer patients’ perceived needs: development and validation of the 34‐item Supportive Care Needs Survey (SCNS‐SF34). J Eval Clin Pract. 2009;15:602–6.

Miles B, Huberman A, editors. Qualitative data analysis: an expended sourcebook. London, UK: Sage Publications; 1994.

Khoury MJ, Gwinn M, Yoon PW, Dowling N, Moore CA, Bradley L. The continuum of translation research in genomic medicine: how can we accelerate the appropriate integration of human genome discoveries into health care and disease prevention? Genet Med. 2007;9:665–74.

Sankila R, Olsen JH, Anderson H, Garwicz S, Glattre E, Hertz H, et al. Risk of cancer among offspring of childhood-cancer survivors. Association of the Nordic Cancer Registries and the Nordic Society of Paediatric Haematology and Oncology. New Engl J Med. 1998;338:1339–44.

Madanat-Harjuoja LM, Malila N, Lahteenmaki P, Pukkala E, Mulvihill JJ, Boice JD Jr., et al. Risk of cancer among children of cancer patients - a nationwide study in Finland. Int J cancer. 2010;126:1196–205.

Reinmuth S, Liebeskind AK, Wickmann L, Bockelbrink A, Keil T, Henze G, et al. Having children after surviving cancer in childhood or adolescence - results of a Berlin survey. Klin Padiatr. 2008;220:159–65.

Klitzman RL. Misunderstandings concerning genetics among patients confronting genetic disease. J Genet Couns. 2010;19:430–46.

Lim Q, McGill BC, Quinn VF, Tucker KM, Mizrahi D, Patenaude AF, et al. Parents’ attitudes toward genetic testing of children for health conditions: a systematic review. Clin Genet. 2017;92:569–78.

McGill BC, Wakefield CE, Vetsch J, Barlow-Stewart K, Kasparian NA, Patenaude AF, et al. Children and young people’s understanding of inherited conditions and their attitudes towards genetic testing: a systematic review. Clin Genet. 2019;95:10–22.

Wakefield CE, Hanlon LV, Tucker KM, Patenaude AF, Signorelli C, McLoone JK, et al. The psychological impact of genetic information on children: a systematic review. Genet Med. 2016;18:755.

Vetsch J, Wakefield CE, Warby M, Tucker K, Patterson P, McGill BC, et al. Cancer-related genetic testing and personalized medicine for adolescents: a narrative review of impact and understanding. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2018;7:259–62.

Roberts JS, Robinson JO, Diamond PM, Bharadwaj A, Christensen KD, Lee KB, et al. Patient understanding of, satisfaction with, and perceived utility of whole-genome sequencing: findings from the MedSeq Project. Genet Med. 2018;20:1069–76.

Malek J, Slashinski MJ, Robinson JO, Gutierrez AM, Parsons DW, Plon SE, et al. Parental perspectives on whole-exome sequencing in pediatric cancer: a typology of perceived utility. JCO Precision. Oncology. 2017;1:1–10.

Acknowledgements

We thank Emma Doolan, Lucy Hanlon, Gabrielle Georgiou, Alison Young, Lachlan Munro, Luke Fry and Sanaa Mathur for their contributions to this research. We also thank each of the recruiting sites for this study, including Sydney Children’s Hospital Randwick, the Children’s Hospital at Westmead, John Hunter Children’s Hospital, the Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne, Monash Children’s Hospital Melbourne, Lady Cilento Children’s Hospital Brisbane (formerly Royal Children’s Hospital Brisbane), Perth Children’s Hospital (formerly Princess Margaret Hospital for Children), Women’s and Children’s Hospital Adelaide, and in New Zealand, Starship Children’s Health, Wellington Hospital and Christchurch Hospital. We thank Joanna Fardell (PhD) and Kate Hetherington (PhD) for conducting some interviews. We thank Mark Donoghoe for his statistical support. CEW is supported by a Career Development Fellowship from the NHMRC of Australia (APP1143767). CS is supported by The Kids’ Cancer Project. The Behavioural Sciences Unit (BSU) is proudly supported by the Kids with Cancer Foundation.

*ANZCHOG Survivorship Study Group:

*The members of the ANZCHOG Survivorship Study Group in alphabetical order: Dr Frank Alvaro, Professor Richard Cohn, Dr Rob Corbett, Dr Peter Downie, Ms Karen Egan, Ms Sarah Ellis, Professor Jon Emery, Dr Joanna Fardell, Ms Tali Foreman, Dr Melissa Gabriel, Professor Afaf Girgis, Ms Kerrie Graham, Ms Karen Johnston, Dr Janelle Jones, Dr Liane Lockwood, Dr Ann Maguire, Dr Maria McCarthy, Dr Jordana McLoone, Dr Francoise Mechinaud, Ms Sinead Molloy, Ms Lyndal Moore, Dr Michael Osborn, Dr Christina Signorelli, Dr Jane Skeen, Dr Heather Tapp, Ms Tracy Till, Ms Jo Truscott, Ms Kate Turpin, Professor Claire Wakefield, Dr Thomas Walwyn, Ms Jane Williamson and Ms Kathy Yallop.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vetsch, J., Wakefield, C.E., Tucker, K.M. et al. Genetics-related service and information needs of childhood cancer survivors and parents: a mixed-methods study. Eur J Hum Genet 28, 6–16 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-019-0481-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-019-0481-7

This article is cited by

-

Sexual and reproductive complications and concerns of survivors of childhood, adolescent and adult cancer

Journal of Cancer Survivorship (2023)

-

Factors associated with the comprehensive needs of caregivers of childhood cancer survivors in Korea

Journal of Cancer Survivorship (2022)