Abstract

Guidelines recommend that providers engage patients in shared decision-making about receiving incidental results (IR) prior to genomic sequencing (GS), but this can be time-consuming, given the myriad of IR and variation in patients’ preferences. We aimed to develop patient profiles to inform pre-test counseling for IR. We conducted semi-structured interviews with participants as a part of a randomized trial of the GenomicsADvISER.com, a decision aid for selecting IR. Interviews explored factors participants considered when deliberating over learning IR. Interviews were analyzed by thematic analysis and constant comparison. Participants were mostly female (28/31) and about half of them were over the age of 50 (16/31). We identified five patient profiles that reflect common contextual factors, attitudes, concerns, and perceived utility of IR. Information Enthusiasts self-identified as “planners” and valued learning most or all IR to enable planning and disease prevention because “knowledge is power”. Concerned Individuals defined themselves as “anxious,” and were reluctant to learn IR, anticipating negative psychological impacts from IR. Contemplators were discerning about the value and limitations of IR, weighing health benefits with the impacts of not being able to “un-know” information. Individuals of Advanced Life Stage did not consider IR relevant for themselves and primarily considered their implications for family members. Reassurance Seekers were reassured by previous negative genetic test results which shaped their expectations for receiving no IR: “hopefully [GS will] be negative, too. And then I can rest easy”. These profiles could inform targeted counseling for IR by providing a framework to address common values, concerns. and misconceptions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Widespread uptake of genome sequencing (GS) poses service delivery challenges, particularly given the scope and volume of secondary and incidental results (IR) that can be generated; there is a need for clinical tools and conceptual frameworks to support practitioners in delivering these results [1, 2]. Policy recommendations on the return of these results vary. The European Society of Human Genetics (ESHG) recommends targeted approaches to limit the generation of results unrelated to the reason for testing and with unknown clinical utility, but recommends that results associated with serious but treatable health problems should be returned if detected [3]. Similarly, the Canadian College of Medical Genetics (CCMG) supports targeted approaches that limit the identification of IR, but if approaches that could lead to the identification of IR are used, CCMG recommends that competent adults should be given the choice to receive or not receive IR prior to testing [4]. Conversely, the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) recommend the return of medically actionable secondary findings, with the option for patients to “opt out” of learning these results [5]. This list of medically actionable results only represents a small fraction of the findings that may be revealed through GS and does not account for the variability observed in patients’ preferences toward learning non-actionable and other forms of IR [6, 7]. We have chosen to use the term IR for the purposes of this study, as it encompasses a broader range of results that include actionable and non-actionable results, risks for polygenic diseases, and carrier status, whereas the term secondary findings refers to medically actionable results that are deliberately sought [5].

Research shows that many patients are enthusiastic about learning different types of IR, and express confidence in the utility associated with learning GS results [6]. However, a minority of patients choose not to learn IR [8]. Patients express varied preferences depending on the type of IR offered [9], value choice about which IR they learn [9], and prefer shared decision-making [10]. Pre-test shared decision-making is important to ensure patients make informed and value-congruent decisions about learning IR, but the scope and volume of IR makes traditional models of pre-test counseling unfeasible [1]. There is a need for innovative clinical tools such as decision aids that enable clinicians to engage more efficiently in shared decision-making with their patients [11]. Bombard et al. developed a decisional aid (GenomicsADvISER.com) to support the clinical adoption of GS and informed selection of IR [12, 13]. Usability testing revealed that participants found the decision aid acceptable and intuitive to use, with all indicating that it provided sufficient information for them to reach an informed, value-congruent decision [12]. Given that decision aids will likely be able to augment but not replace in-person pre-test counseling [12], there is still a need to develop targeted approaches to shared decision-making that will be sustainable given limited genetics resources.

One approach to tailor genetic counseling efforts is to identify patient profiles, which characterize patient preferences, attitudes, and expectations toward GS and learning IR. The concept of patient profiles is similar to that of “user profiles” or "personas" that initially emerged from the product marketing field [14]. This concept has been adopted in health education in an effort to tailor educational strategies to the unique preferences and informational needs of specific clinical populations [14]. These profiles are essentially hypothetical representations of target users, based upon a set of shared characteristics, preferences, and/or attitudes [15, 16]. Patient profiles have been applied to many chronic health conditions, such as coronary artery disease and diabetes [14,15,16], and offer significant potential for pre-test counseling. The identification of patient profiles would enable clinicians to tailor their education and decisional support to patients’ needs, and efficiently address common concerns or areas of misunderstanding, which could ultimately support the ability of genetics services to respond to the demands posed by GS.

Currently, research exploring patient engagement with GS is limited to exploring patients' preferences about the return of IR, not characterizing preferences about specific categories of results [6, 8, 9, 17]. The first aim of our qualitative study was to explore patients’ preferences toward hypothetically learning five categories of IR. The findings of the first aim will be described in a paper that is currently under development. Our second aim was to characterize patient profiles that emerged from the analysis. To do so, we characterized the groupings of participants that emerged, based on shared attributes and characteristics in their decisions related to learning IR.

Methods

We used qualitative methodology and semi-structured interviews to explore factors that influence participants’ hypothetical selections of categories of IR from GS. Qualitative methods were selected as they provide rich data on individual experiences and perspectives [18].

Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Boards at St. Michael’s Hospital, Mount Sinai Hospital and Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto, Canada.

Participants and recruitment

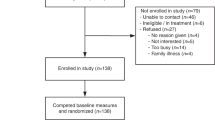

We recruited participants from a sample of 133 patients participating in a randomized controlled trial of a decision aid (www.GenomicsADvISER.com) for the selection of IR from GS [12, 13]. All participants had been seen at a cancer genetics clinic in Toronto, ON, had previously had single gene or panel testing related to their personal and/or family history of cancer, and had received an inconclusive negative result (no variant identified). As part of the RCT [13], participants either used the decision aid (Fig. 1) or spoke with a genetic counselor over the phone and selected categories of IR that they would hypothetically choose to learn if they were offered GS. A subset of participants from both arms of the RCT were recruited for this qualitative study.

Participants selected IR from five categories that were based on a proposed framework: (1) medically actionable results, (2) common disease risks, (3) rare Mendelian diseases, (4) early-onset brain diseases, and (5) carrier status (Fig. 2) [19]. Initially, participants were purposively sampled based on their category selection and sociodemographic characteristics, seeking variability in those characteristics, consistent with the maximal variation sampling approach [20]. For instance, we sought out participants who had selected all categories, few or no categories, and unique combinations of categories. We also sought out participants with underrepresented sociodemographic characteristics.

As data analysis progressed, our sampling strategy was informed by findings that emerged from our analysis. We sought to maximize the similarities and differences related to the developing themes or profiles, referred to as theoretical sampling [21], in order to characterize the range of profiles in our sample [22]. To achieve this, we recruited participants who expressed novel or unique perspectives during their discussion with the study genetic counselor or who differed in sociodemographic characteristics from participants that we had previously spoken to. We also recruited individuals whose characteristics or views expressed in their discussion with the study genetic counselor seemed to align with profiles we had encountered less frequently, to more fully describe the characteristics and perspectives of those profiles. We continued this process until we had reached saturation, that is, we had captured the range of profiles in our sample, and no new profiles were identified.

Data collection

We conducted in depth, semi-structured phone interviews with participants between April 2017 and November 2017. Interviews explored factors that influenced their selections of categories of IR, their perspectives on IR and GS, perceived utility of IR, and past experiences with genetic testing (Appendix 1). All interviews were conducted by CM or LC. The initial interview guide was developed based on a literature review and the research aims, and iteratively modified as analysis progressed. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Interviewers took detailed field notes following each interview.

Data analysis

We employed thematic analysis informed by a grounded theory approach and constant comparison [23]. Thematic analysis involved identifying groupings of participants or profiles. Interviews were coded independently by LC, CM, SC, EJ, LM, with supervision by MC. The initial codebook was developed based on the interview guide, and iteratively modified as codes and themes emerged from interview data through constant comparison. This iterative process of constant comparison involved reflecting on our findings, comparing emergent and existing findings, and subsequently modifying our interview guide, coding framework, analysis, and sampling strategy based on our findings. This process occurred repeatedly throughout our analysis.

To build consistency in coding and contribute to rigor, multiple coders coded 11 transcripts. For the transcripts that were coded by multiple coders, differences in coding were resolved through discussion. Coders reviewed coded transcripts together, and in places where the assigned codes differed, coders discussed the codes until they reached consensus, and recoded the transcripts. There were regular team meetings to discuss coding, analysis, the interview guide, and the sampling strategy. Analytic decisions that resulted from these meetings were documented.

Initial interviews and analysis broadly explored participants’ preferences and attitudes toward different types of IR. In this initial analysis, we sought to identify themes related to patients’ decision-making process and preferences toward hypothetically learning IR, consistent with our first aim. The findings of this stage of the analysis will be reported in a paper that is currently under development. From this analysis, we observed that patients clustered into different groups based on core characteristics that informed their selections of IR, such as their attitudes toward IR. We subsequently sought to characterize these emergent patient profiles, consistent with our second aim.

Subsequent interviews and stages of analysis sought to better understand the core characteristics that informed preferences toward IR, and how these characteristics were shared among groups of participants. By identifying common groupings of these characteristics, we developed “patient profiles” that represent subgroups of patients that are distinguished by factors that informed their IR selections. The development of patient profiles was based on the development of “user profiles,” an established technique in user-centered design, which aims to construct a conceptual model of patients’ experiences, expectations, and engagement with novel technologies [16]. There are multiple methods for developing user profiles, one of which is thematic analysis of interview data [15, 16], wherein profiles are first identified based on open coding and updated through axial and selective coding as analysis progresses [16]. Consistent with this methodology, based on our initial rounds of coding we described preliminary patient profiles [16]. In an iterative fashion, subsequent rounds of analysis aimed to identify further attributes that delineated each profile. The iterative process involved reflecting on groupings of participants or profiles, and modifying our analysis and sampling strategy based on these emergent findings.

Results

We interviewed 31 patients. Participants were predominately female (28/31), college or university educated (30/31), and White/of European descent (20/31) (Table 1). About half of the participants were over 50 years old (16/31) and born in Canada (16/31). Most (20/31) of the participants were affected by cancer, predominately breast (16/20) (Table 1). The high number of female participants reflect the participants in the RCT and is likely due to the fact that patients in the RCT were recruited from clinics that see high volumes of patients affected by or at elevated risk for breast and ovarian cancer, who are predominately female.

We identified a set of characteristics that informed participants’ decisions about IR and shaped their preferences for categories of IR. These characteristics included contextual factors (life stage, family context, disease experience), self-definition, attitude toward IR, concerns about IR, and perceived utility of IR. Based on how these characteristics clustered among groups of participants, we identified five patient profiles: Information Enthusiasts, Concerned Individuals, Contemplators, Individuals of Advanced Life Stage, Reassurance Seekers (Table 2).

Information Enthusiasts

Many individuals in our sample aligned with this profile. Information Enthusiasts tended to be middle-aged and have children. Information Enthusiasts self-identified as being “planners,” which contributed to a high level of interest in learning IR to enable them to prepare for the future.

“I’m very much for planning and being prepared. And, also if there are things I’m doing that I should be doing differently that could make a difference in the end result kind of thing, then I would want to know what those things were more specifically.”—SB03

These participants were eager to learn their genetic information and inherently valued access to IR, with multiple participants stating that, “knowledge is power.” IR had broad utility for these participants. InformationEnthusiasts prioritized medical actionability, specifically in relation to Categories 1: Medically Actionable and 2: Common Disease Risks, where concrete medical and/or lifestyle modifications were available to reduce their disease risk. In some cases, participants described how personal experiences with cancer and genetic testing contributed to the value they saw in IR, particularly medically actionable IR. At the same time, they employed a broader definition of actionability to also include planning for the future, sharing information with family members, and seeking more information about their results, such as on the Internet or through consulting with specialists. In addition, these participants anticipated future medical actionability in relation to Categories 3: Rare Genetic Diseases and 4: Early-Age Brain Diseases. These participants often described hope for future prevention strategies or treatments through medical advances (i.e. clinical trials). Therefore, all categories of IR could be useful. Given the value that Information Enthusiasts placed on information, they tended to select all categories of IR, but not in all cases. Regardless of which categories they chose, these participants exhibited confidence in their decisions.

Concerned Individuals

Few participants in our sample aligned with this profile. Concerned Individuals had typically had a distressing experience with genetic testing or a profound health experience that influenced how they thought about IR. For instance, one woman had previously received an intermediate result from a tumor profiling test to assess her risk of breast cancer recurrence. This caused substantial uncertainty regarding whether she should pursue chemotherapy, and both she and her physician regretted ordering the test. This had been extremely distressing for the participant, and she stated that she subsequently was reluctant to pursue any further genetic testing.

“I’ve learned my lesson after my Oncotype testing. If someone offered me another test, I don’t want to do it. It’s because I realize I can’t handle the consequences. I can’t handle the stress related to it.”—SB18

Concerned Individuals tended to self-identify as being “anxious,” and expressed concerns related to learning IR. Concerns about the emotional and psychological burden of knowing one’s disease risk were particularly salient.

“I really feel like the emotional component is the one that I was struggling with the most. Because, I do not believe I really fully understand what I can handle and what I can’t handle.”—SB27

Participants also expressed concerns about the uncertain predictive value of IR, and one Concerned Individual described concerns about the security of the data generated from GS, and the possibility for insurance discrimination. Concerned Individuals described the overall utility of IR as being lower than Information Enthusiasts did. While they acknowledged how IR could inform future medical actions, they weighed this utility against the psychological burden of living with this knowledge. Subsequently, Concerned Individuals typically did not select any categories of IR or selected very few categories.

Contemplators

Contemplators tended to be younger than other participants. These participants did not express a high degree of enthusiasm toward IR, nor did they express concerns to the degree that Concerned Individuals did.

“It’s a tricky thing […] I absolutely want to be informed […] Then at the same time, once you know something, you can’t really un-know it.”—MK42

Contemplators recognized the potential value of learning IR for informing medical actions, lifestyle changes, and planning for the future. At the same time, these individuals were discerning about the lack of available actions for particular categories of IR, the potential for negative emotional impacts, and the uncertainty inherent to disease risks associated with IR.

“One of the things around knowing, let’s say if you’re going to have Alzheimer’s [disease], is just the idea around, you know, oh I’m going to live my life now. But, what does that mean? Does that mean you take all of your savings, quit your job, do everything you want to do and then…and then what? And then, what if you actually don’t get Alzheimer’s [disease] and then you ended up never really having a career. You end up being like really poor in retirement. And perfectly healthy and live till 90. Like, what do you do then, right? You start deciding I will get it and you start living your life in a way that may not even happen?”—FG19

These individuals engaged in extensive deliberation over learning IR and weighed the perceived risks and benefits along with their values and lived experiences to reach their hypothetical category selection. These individuals often reflected on how their own viewpoint might differ from others, which seemed to contribute to clarifying their own preferences and building confidence in their decision. Contemplators typically selected multiple categories of IR, but expressed the most concern about, and therefore in some cases did not select, Categories 3: Rare Genetic Diseases and 4: Early-Age Brain Diseases.

Individuals of Advanced Life Stage

For Individuals of Advanced Life Stage, life stage and life experiences were particularly important in shaping preferences for IR. These participants typically had adult children for whom they expressed a sense of responsibility, and who represented a key determinant of their IR preferences. Individuals of Advanced Life Stage also typically drew on their own experiences with a serious illness or the experience of a close friend or family member in making sense of their preferences for IR. Since these participants were past the age of onset for many diseases associated with IR, learning IR to inform medical actions or lifestyle changes to reduce their disease risk was described as less important or even irrelevant. Instead, these participants considered whether learning this genetic information would be important for their relatives. Furthermore, these individuals were past the age of making reproductive decisions, so carrier status was also not perceived as personally relevant, but might be important for their children. Overall, these participants focused on how specific IR could support their quality of life and that of their family members. For example, these participants described how knowing their risk for debilitating conditions such as Alzheimer disease could allow them to plan to alleviate burden on their children, such as by making arrangements for appropriate housing or planning their estate ahead of time.

“I don’t want to be a burden on my kids […] As much as I know they would be there for me, I would want to do everything ahead of time.”—SB31

Individuals of Advanced Life Stage varied in their category selections, but typically selected multiple or all categories of IR.

Reassurance Seekers

Few individuals in our sample reflected this profile, and they expressed a very different viewpoint toward learning IR than the other profiles. Reassurance Seekers’ attitudes toward IR were largely shaped by their past experience with genetic testing. These participants (as had all participants in the study) had undergone genetic testing related to their cancer, and no variants were identified. This negative result had provided participants in this profile with a sense of relief and reassurance that they did not carry a genetic risk for cancer. These individuals expressed a hope, or even an expectation, that if they were to undergo GS and elect to learn IR, all of the categories would come back “negative,” and therefore reassure them that they were not at elevated risk for incidental diseases. These participants exhibited misconceptions about GS and the incidence of IR, which contributed to their expectations that they would be unlikely to receive any positive IR. The idea of receiving multiple types of IR was concerning for these participants. These participants varied in their category selections but tended to select multiple or all categories, as this would provide them with reassurance about multiple types of diseases.

“I want to participate in any learning possible and because I already had a negative one, let’s just do it and get the rest of it, and it’ll hopefully be negative, too. And then I can rest easy and sleep well.”—MK40

Interestingly, the Concerned Individual referred to earlier (SB18) had approached her tumor profiling as a Reassurance Seeker, hoping for reassurance that she would be recommended to pursue chemotherapy. However, she received an intermediate result that was not what she had anticipated, which had negative psychological impacts. While tumor profiling differs greatly from GS, this experience caused SB18 anxiety about other medical appointments and pursuing any other types of genetic or genomic testing.

“I think it’s because I wanted that reassurance at the time [that I pursued testing]. That’s why I didn’t think it was anything bad. So, when the result came out, I was depressed because it was not what I anticipated.”—SB18

It is important to note that not all participants aligned with one profile; few participants exhibited traits of multiple profiles. Few participants also began the interview aligned with one profile, but in deliberating throughout the interview, ultimately changed their overall views toward IR and concluded the interview aligned with a different profile.

Discussion

We identified five patient profiles—Information Enthusiasts, Concerned Individuals, Contemplators, Individuals of Advanced Life Stage, and Reassurance Seekers—that reflect common attitudes, concerns, and perceived utility of GS and IR, as well as personal and contextual factors. These patient profiles could support the clinical delivery of GS by informing tailored pre-test counseling. Clinical genetics resources are already strained [24], and as GS is adopted more widely, it will be essential to determine how to use limited clinical resources efficiently [1]. Tailoring counseling to patients’ preferences and individual decisional needs may reduce the time needed for consultation [25]. Considering patient profiles could help clinicians tailor counseling by identifying common values, concerns, and misconceptions related to IR, and targeting their counseling of patients accordingly.

For instance, if counseling an Information Enthusiast, the clinician may wish to ensure that patients understand the limitations of the information that GS provides. If counseling a patient who seems to be a Concerned Individual, a clinician could focus on providing emotional support, and be aware that these patients may decline sequencing or IR. Concerned Individuals may also have concerns about the limitations of the technology, which providers could spend time exploring. For Contemplators, clinicians could ensure that participants have ample time to weigh the risks and benefits of GS, and that they are able to engage in deliberative discussion. For Individuals of Advanced Life Stage, counseling that emphasizes implications of IR for family members may be more relevant than counseling that emphasizes disease prevention. If counseling a patient who appears to be a Reassurance Seeker, the clinician may wish to dedicate time to ensuring that the patient truly understands the meaning of a negative result. These patients may misunderstand the meaning of their previous genetic testing as well as the implications of IR. Providers should address what is essentially a false sense of security and ensure that patients understand that even if no genetic risk is found, that does not necessarily indicate that a patient is risk-free. Providers may also wish to address patients’ expectations of receiving negative results and ensure that they are adequately prepared to possibly receive a positive result, as they otherwise may experience psychological distress related to that result and future genetic tests.

It will be important for providers to be aware that patients may shift in their profiles as they deliberate, or exhibit traits of multiple profiles. However, even for patients that reflect overlapping profiles, the profiles can still provide a framework for identifying salient values and concerns. These profiles present a conceptual framework that could facilitate identification of patients’ values, misperceptions, and concerns to tailor their educational and decisional support, effectively targeting counseling based on what is most salient for that patient. Profiles could help providers identify topics that may require additional time, without necessarily deemphasizing or ignoring other topics. It will also be important for providers to be sensitive to preferences, values, and concerns that may diverge from those that are captured by the profiles, and to not make rapid assumptions about patients’ preferences. Our intent is that clinicians can use patient profiles as a framework to situate their patient and target their counseling accordingly. Further research should address the development and evaluation of clinical measures to facilitate the identification of patient profiles in practice. For instance, one such measure could involve a questionnaire for patients to complete prior to seeing their clinician, to characterize patients’ profile based on their responses. The provider could subsequently target their counseling accordingly.

While others have identified subgroups of patients that differ in how they engage with GS [26, 27], it is unclear how consideration of these subgroups could be translated into clinical care. This study presents a novel contribution in that we propose a model for clinicians to identify common characteristics among patients and tailor their counseling about IR accordingly. Others have identified “early adopters” who are high in dispositional optimism and resilience [26], “enthusiasts” who perceive a high degree of personal and medical utility in GS results, “skeptics” who perceive low utility in GS results, and “health conscious” who perceive medical but not personal utility [27]. Our study is novel in that it explores patient engagement with specific types of IR, which differs from previous studies that characterize patients based on their attitudes toward GS results broadly without an explicit focus on IR [26, 27]. In addition, our study enriches what is known about patient subgroups, as we identify subgroups that have not been previously described and delineates additional characteristics that influence how patients engage with decisions about IR. Characteristics that influence how patients make decisions about undergoing GS may also influence how they respond to and act on results [26, 27]. Overall, there is limited research on the psychosocial and behavioral impacts of IR [28]. Further research could address whether patients of different profiles respond differently to learning IR, and act upon IR in different ways.

This study has several limitations. First, participants made a hypothetical decision, and decisions regarding actual receipt of IR may differ [29]. Second, participants in our sample were mostly female and educated, and demographic diversity was limited. This may limit the transferability of our findings to males or to patients with lower educational backgrounds. The demographics of our sample reflect populations that typically participate in genetic research and studies involving GS [26, 27, 30], a limitation in the field that should be addressed in future studies; efforts should be made to engage participants from underrepresented populations. A further limitation is that all patients in our study had a family history of cancer and the majority had been affected by cancer (20/31). Furthermore, all patients had previously received genetic counseling and genetic testing related to cancer. These characteristics limit the transferability of our findings. Further research is needed to validate these profiles in larger and more diverse populations of individuals not affected by cancer.

Despite these limitations, our study provides a novel conceptual framework for the use of patient profiles with the potential to inform pre-test counseling for IR. These results indicate that a one-size-fits-all approach to pre-test counseling for IR will not be appropriate. There is a need to tailor pre-test counseling; with further research and validation, patient profiles could provide efficiencies in pre-test counseling by allowing providers to target shared decision-making toward salient issues for each patient. Efficient counseling strategies are required given limited genetics resources and the increasing use of GS beyond speciality genetics clinics by providers with limited genomics expertise.

References

Schmidlen T, Sturm AC, Hovick S, Scheinfeldt L, Roberts S, Morr L, et al. Operationalizing the reciprocal engagement model of genetic counseling practice: a framework for the scalable delivery of genomic counseling and testing. J Genet Couns. 2018;27:1111–29.

Burke W, Antommaria AH, Bennett R, Botkin J, Clayton EW, Henderson GE, et al. Recommendations for returning genomic incidental findings? We need to talk! Genet Med. 2013;15:854–9.

van El CG, Cornel MC, Borry P, Hastings RJ, Fellman F, Hodgson SV, et al. Whole-genome sequencing in health care: recommendations of the European Society of Human Genetics. Eur J Hum Gen. 2013;21:580–4.

Boycott K, Hartley T, Adam S, Bernier F, Chong K, Fernandez BA, et al. The clinical application of genome-wide sequencing for monogenic diseases in Canada: position statement of the Canadian college of medical geneticists. J Med Genet. 2015;52:431–7.

Kalia SS, Adelman K, Bale SJ, Chung WK, Eng C, Evans JP, et al. Recommendations for reporting of secondary findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing, 2016 update (ACMG SF v2.0): a policy statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. Genet Med. 2017;19:249–55.

Facio FM, Eidem H, Fisher T, Brooks S, Linn A, Kaphingst KA, et al. Intentions to receive individual results from whole-genome sequencing among participants in the ClinSeq study. Eur J Hum Genet. 2013;21:261–5.

Bennette CS, Trinidad SB, Fullerton SM, Patrick D, Amendola L, Burke W, et al. Return of incidental findings in genomic medicine: measuring what patients value--development of an instrument to measure preferences for information from next-generation testing (IMPRINT). Genet Med. 2013;15:873–81.

Fiallos K, Applegate C, Mathews DJH, Bollinger J, Bergner AL, James CA. Choices for return of primary and secondary genomic research results of 790 members of families with Mendelian disease. Eur J Hum Genet. 2017;25:530–7.

Kaphingst KA, Ivanovich J, Biesecker BB, Dresser R, Seo J, Dressler LG, et al. Preferences for return of incidental findings from genome sequencing among women diagnosed with breast cancer at a young age. Clin Genet. 2016;89:378–84.

Matsen CB, Lyons S, Goodman MS, Biesecker BB, Kaphingst KA. Decision role preferences for return of results from genome sequencing amongst young breast cancer patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;1:155–61.

Birch PH. Interactive e-counselling for genetics pre-test decisions: where are we now? Clin Genet. 2015;87:209–17.

Bombard Y, Clausen M, Mighton C, Carlsson L, Casalino S, Glogowski E, et al. The Genomics ADvISER: development and usability testing of a decision aid for the selection of incidental sequencing results. Eur J Hum Genet. 2018;26:984–95.

Shickh S, Clausen M, Mighton C, Casalino S, Joshi E, Glogowski E, et al. Evaluation of a decision aid for incidental genomic results, the Genomics ADvISER: protocol for a mixed methods randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e021876.

Vosbergen S, Mulder-Wiggers JM, Lacroix JP, Kemps HM, Kraaijenhagen RA, Jaspers MW, Peek N. Using personas to tailor educational messages to the preferences of coronary heart disease patients. J Biomed Inform. 2015;53:100–12.

Holden RJ, Kulanthaivel A, Purkayastha S, Goggins KM, Kripalani S. Know thy eHealth user: Development of biopsychosocial personas from a study of older adults with heart failure. Int J Med Inform. 2017;108:158–67.

LeRouge C, Ma J, Sneha S, Tolle K. User profiles and personas in the design and development of consumer health technologies. Int J Med Inform. 2013;82:e251–68.

Townsend A, Adam S, Birch PH, Lohn Z, Rousseau F, Friedman JM. “I want to know what’s in Pandora’s Box”: comparing stakeholder perspectives on incidental findings in clinical whole genomic sequencing. Am J Med Genet A. 2012;158a:2519–25.

Charmaz KC. Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.; 2006.

Berg JS, Khoury MJ, Evans JP. Deploying whole genome sequencing in clinical practice and public health: meeting the challenge one bin at a time. Genet Med. 2011;13:499–504.

Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, Wisdom JP, Duan N, Hoagwood K. Purposeful Sampling for Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis in Mixed Method Implementation Research. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2015;42:533–44.

Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 2nd edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998.

Coyne IT. Sampling in qualitative research. Purposeful and theoretical sampling; merging or clear boundaries? J Adv Nurs. 1997;26:623–30.

Strauss AL, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990.

McCuaig JM, Armel SR, Care M, Volenik A, Kim RH, Metcalfe KA. Next-generation service delivery: a scoping review of patient outcomes associated with alternative models of genetic counseling and genetic testing for hereditary cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2018;10. pii: E435.

Salemink S, Dekker N, Kets CM, van der Looij E, van Zelst-Stams WA, Hoogerbrugge N. Focusing on patient needs and preferences may improve genetic counseling for colorectal cancer. J Genet Couns. 2013;22:118–24.

Lewis KL, Han PK, Hooker GW, Klein WM, Biesecker LG, Biesecker BB. Characterizing participants in the clinseq genome sequencing cohort as early adopters of a new health technology. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0132690.

Lupo PJ, Robinson JO, Diamond PM, Jamal L, Danysh HE, Blumenthal-Barby J, et al. Patients’ perceived utility of whole-genome sequencing for their healthcare: findings from the MedSeq project. Per Med. 2016;13:13–20.

Yanes T, Willis AM, Meiser B, Tucker KM, Best M. Psychosocial and behavioral outcomes of genomic testing in cancer: a systematic review. Eur J Hum Genet.; e-pub ahead of print 11 September 2018; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-018-0257-5.

Sanderson SC, O’Neill SC, Bastian LA, Bepler G, McBride CM. What can interest tell us about uptake of genetic testing? Intention and behavior amongst smokers related to patients with lung cancer. Public Health Genom. 2010;13:116–24.

Gonzalez BD, Hoogland AI, Kasting ML, Cragun D, Kim J, Ashing K, et al. Psychosocial impact of BRCA testing in young black breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2018;27.2778–85.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the University of Toronto McLaughlin Centre. YB was supported by a CIHR New Investigator Award during this study. CM received support from the Research Training Centre at St. Michael's Hospital, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (FRN #160968) and from a studentship funded by the Canadian Centre for Applied Research in Cancer Control (ARCC). ARCC receives core funding from the Canadian Cancer Society (Grant #2015-703549). JGH was supported by NCI P30 CA008748. We would like to thank Theresa H. Kim for her contributions to the statistical analysis in the RCT, and her contributions to recruitment. We would like to thank Nasim Monfared, Oana Morar, Leslie Ordal and Nicholas Watkins for their support on the study. Finally, we would like to thank our interview participants for their time and valuable insights.

Incidental Genomics Study Team

Yvonne Bombard (PI), Susan Armel, Nancy Baxter, Ahmed Bayoumi, Ken Bond, June C. Carroll, Timothy Caulfield, Tammy Clifford, Irfan Dhalla, Craig Earle, Andrea Eisen, Christine Elser, Michael Evans, Emily Glogowski, Jada Hamilton, Wanrudee Isaranuwatchai, Monica Kastner, Raymond H. Kim, Andreas Laupacis, Jordan Lerner-Ellis, Michelle Mujoomdar, Yvonne Bombard (PI), Susan Armel, Nancy Baxter, Ahmed Bayoumi, Ken Bond, June C. Carroll, Tammy Clifford, Timothy Caulfield, Iris Cohn, Irfan Dhalla, Craig Earle, Andrea Eisen, Christine Elser, Emily Glogowski, Jada G. Hamilton, Wanrudee Isaranuwatchai, Monika Kastner, Raymond H. Kim, Andreas Laupacis, Jordan Lerner-Ellis, Kenneth Offit, Seema Panchal, Mark Robson, Adena Scheer, Stephen W. Scherer, Kasmintan Schrader, Terrance Sullivan and Kevin E. Thorpe.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Members of Incidental Genomics Study Team are listed below the Acknowledgements section.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mighton, C., Carlsson, L., Clausen, M. et al. Development of patient “profiles” to tailor counseling for incidental genomic sequencing results. Eur J Hum Genet 27, 1008–1017 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-019-0352-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-019-0352-2

This article is cited by

-

Secondary use of genomic data: patients’ decisions at point of testing and perspectives to inform international data sharing

European Journal of Human Genetics (2024)

-

Great expectations: patients’ preferences for clinically significant results from genomic sequencing

Human Genetics (2023)

-

Widening the lens of actionability: A qualitative study of primary care providers’ views and experiences of managing secondary genomic findings

European Journal of Human Genetics (2022)

-

A comprehensive genomic reporting structure for communicating all clinically significant primary and secondary findings

Human Genetics (2022)

-

Patient and public preferences for being recontacted with updated genomic results: a mixed methods study

Human Genetics (2021)