Abstract

There are several key unsolved issues relating to the clinical use of next generation sequencing, such as: should laboratories report variants of uncertain significance (VUS) to clinicians and/or patients? Should they reinterpret VUS in response to growing knowledge in the field? And should patients be recontacted regarding such results? We systematically analyzed 58 consent forms in English used in the diagnostic context to investigate their policies for (a) reporting VUS, (b) reinterpreting variants, including who should initiate this, and (c) recontacting patients and the mechanisms for undertaking any recontact. One-third (20/58) of the forms did not mention VUS in any way. Of the 38 forms that mentioned VUS, only half provided some description of what a VUS is. Approximately one-third of forms explicitly stated that reinterpretation of variants for clinical purposes may occur. Less than half mentioned recontact for clinical purposes, with variation as to whether laboratories, patients, or clinicians should initiate this. We suggest that the variability in variant reporting, reinterpretation, and recontact policies and practices revealed by our analysis may lead to diffused responsibility, which could result in missed opportunities for patients or family members to receive a diagnosis in response to updated variant classifications. Finally, we provide some suggestions for ethically appropriate inclusion of policies for reporting VUS, reinterpretation, and recontact on consent forms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A major challenge associated with the clinical implementation of high throughput next-generation sequencing technologies (NGS), such as sequencing of exomes, genomes, and gene panels, is the large number of variants identified [1,2,3]. Distinguishing which of these variants affect function and are potentially causative of the phenotype of the patient, from those which are not, is time consuming [4], and complex; even experienced laboratory personnel have identified the classification of variants from diagnostic NGS as a real challenge [5]. Despite the growing knowledge in the field and the presence of databases that link variants with clinical phenotypes to aid classification (e.g., ClinVar), many of these variants remain difficult to classify as either (likely) benign or (likely) pathogenic in relation to the genetic condition for which testing has been sought [5, 6]. These variants of uncertain significance (VUS) may be (i) in genes known to be related to the clinical question, but where there is a lack of sufficient evidence to confirm or rule out pathogenicity, (ii) in genes where the function is uncertain (yet are potentially candidate genes) but the nature of the DNA change suggests it could affect function, or (iii) in known disease-causing genes unrelated to the clinical question (i.e., VUS unsolicited findings) [1].

Rather than providing-specific recommendations about whether VUS should be reported or not, guidelines issued by professional bodies generally state that laboratories should have clearly documented protocols for the reporting of VUS to clinicians [7,8,9,10]. Interviews with personnel from 24 laboratories sampled across Europe, Canada, and Australasia suggested that laboratories have variable practices when it comes to reporting variants to clinicians. Some limit their reporting to variants that are considered to be causative of the phenotype, while others will report VUS when they are in genes related to the clinical question, or even candidate genes where the gene function is less certain [5]. There has only been one study of six purposefully sampled CLIA certified consent forms in the USA, which identified some variation between laboratories in their policies for reporting VUS [11].

Another issue that has emerged from the clinical use of NGS relates to the potential responsibilities of laboratories to reinterpret VUS in response to the growing knowledge in the field, to reissue reports to clinicians based on any revised classifications, and for clinicians to subsequently recontact patients [12, 13]. There seems to be general agreement that there is no duty for laboratories to routinely reinterpret sequence data, nor for clinicians to recontact patients [8, 12, 13]. However, guidelines issued by EuroGentest have suggested that if new information arises that leads specifically to the reclassification of a variant, the laboratory is responsible for the reanalysis of data, and for reissuing a report and contacting the referring clinician [8]. The recommendations of the Canadian College of Medical Geneticists (CCMG) suggest that patients be informed of the potential for further interpretation, and propose reinterpretation be initiated by the referring physician, rather than the laboratory [7]. Similarly, guidance by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology recommends health professionals should check with laboratories periodically about the status of any VUS, yet suggests laboratories “consider proactive amendment of cases when a variant reported with a near-definitive classification (pathogenic or benign) must be reclassified” [6]. In contrast, researchers in the UK have suggested a ‘joint venture’ model where responsibility for recontact is shared between healthcare professionals and patients [14]. In addition, Ayuso et al. included reinterpretation of results and patient recontact on their proposed minimum list of information points that consent forms for clinical whole genome sequencing should contain [15].

Some research has been undertaken seeking the views and experiences of clinicians and patients on these issues [12,13,14], yet the actual policies and practices of laboratories and clinics relating to variant reinterpretation and recontact are relatively unexplored. Only two studies have assessed these components of consent forms as part of their broader analysis. Both studies identified differences between the policies of laboratories, either in who is responsible for initiating reinterpretation or in whether the possibility for recontact was addressed [11, 16]. However, these studies comprise small samples of consent forms and, to our knowledge, there has been no systematic investigation of consent forms to specifically explore their policies and practices for (a) the reporting of VUS, (b) reinterpretation of variants, and (c) patient recontact.

In order to fill this knowledge gap, we systematically analyzed 58 consent forms being used in the genomic diagnostic context to investigate if and how they discuss VUS. In particular we studied what they state regarding policies for (a) reporting VUS, (b) reinterpreting variants, including who should initiate this, and (c) recontacting patients and the mechanisms for undertaking any such recontact.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

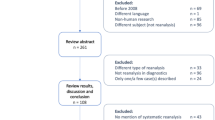

In order to identify consent forms for potential inclusion, we used two complementary strategies. First, an online search was performed by all four researchers independently (March–April 2016) using Google with the search string “(consent form OR informed consent OR consent document) AND (whole-exome sequencing OR whole-genome sequencing OR next generation sequencing OR genome-wide sequencing)”. Researchers reviewed at least the first 10 pages (100 entries) of the results, beyond which results were deemed to be repetitive and no additional forms were being identified. Second, we included additional forms that were known to the researchers to be in use in the clinical setting but were not identified through the online search. These search strategies resulted in a total of 224 URLs for potential inclusion in our analysis.

Following the initial searches, the content found under each URL was then assessed by two of the researchers independently to determine whether they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) an actual consent form requiring the signature of the patient, or their parent/guardian (i.e., not a model form, sample form, or requisition form), (2) explicitly for high throughput sequencing (i.e., next-generation sequencing for large gene panels (i.e., >20 genes), exome or genome sequencing), (3) for use in the clinical/diagnostic setting, and (4) in English. Forms were excluded if their purpose was to obtain consent purely for research purposes.

Data analysis

The consent forms were initially analyzed deductively using a pre-determined list of categories (e.g., VUS, unsolicited findings, etc). This list was developed by all four researchers and based on existing literature. Data from two categories (VUS and data reinterpretation/patient recontact) then became the focus of the analysis and inductive content analysis was used in which categories were derived from the data, rather than pre-determined [17,18,19]. Data for each consent form was coded into subcategories and compared across forms in an iterative manner. Coding was performed by DV and checked by HCH and EN for consistency.

Results

Consent form characteristics

A total of 58 forms met our inclusion criteria. From the 58 forms, 10 were specifically for gaining consent from adult patients, 7 for pediatric patients, and 40 for either adult or pediatric patients, with one form unclear regarding in which patient group it was to be used. These forms were from 40 separate laboratories/clinics (either independent laboratories or affiliated with a hospital/medical center) from 8 different countries (Table 1). A list of these laboratories can be found in Supplementary Table 1.

The results of the inductive content analysis are reported under the following categories: (1) VUS terms and definitions, (2) reporting practices for VUS, (3) reinterpretation and recontact. Some excerpts from the forms have been provided as examples for each category in Table 2.

VUS terms and definitions

A total of 20 of the 58 forms that met our inclusion criteria did not mention VUS in any way. The remaining 38 forms used a variety of terms to refer to VUS (Table 3). The most commonly used terms included variants of/with uncertain significance [10], variants of/with uncertain clinical significance [4], and results of uncertain significance [4]. Eight forms provided a description of what a VUS is, rather than using a specific term. Of the 38 forms that referred to VUS, 11 did not provide a definition or description to explain what a VUS was. Eighteen forms provided an explicit definition, where the term and the description are linked (Table 2, example 1a). For 9/38 forms, although a definition was provided, it was not explicit in that the description was not linked to the term (Table 2, example 1b).

Reporting practices for VUS

Forms were assessed to determine the reporting practices for VUS (Table 3). Nineteen forms explicitly stated that they report VUS (Table 2, example 2a), with reports often being issued to the referring clinician, rather than directly to the patient. An additional 12 forms did not explicitly state that they report VUS but reporting was implied, such as where a form would list VUS as a possible outcome of the test (Table 2, example 2b). The reporting practices of the remaining seven forms were unclear. Some stated their criteria for whether a VUS is reported or not, such as whether the variant is related to the primary clinical question (Table 3), although most forms did not specify which types of VUS they would report. In addition, 15 forms mentioned that they may need to test family members in order to further classify the VUS, with several also suggesting additional information may be required (Table 2, example 2c).

Reinterpretation and recontact

The forms were also analyzed to determine whether they mentioned (a) reinterpretation of variants for clinical purposes, and (b) recontact, which could include either the patient or the clinician being recontacted by the laboratory, the patient recontacting the laboratory, the clinician recontacting the patient, or the patient recontacting the clinician.

a. Reinterpretation

Of the 58 forms that met our inclusion criteria, 25 did not raise the issue of reinterpretation of variants for clinical purposes (Table 4). Twenty-one forms referred to the idea that reinterpretation may take place (Table 2, example 3a). Although, the remaining 12 forms did not explicitly refer to variant reinterpretation, seven mentioned the possibility that variants might be reclassified and five mentioned the possibility of more information coming to light in the future. Only three of the forms sought consent for reinterpretation to be performed and for an updated report to be issued.

Of note is the variation in the ways in which the forms discussed who should initiate any further variant reinterpretation (Table 4). Ten forms indicated that the laboratory will initiate any subsequent variant reinterpretation, with three forms stating that the information will be reviewed every 6 months (Table 2, example 3b). Six forms indicated that the clinician needs to initiate the reinterpretation and five leave it to the patient to initiate the reinterpretation (Table 2, example 3c).

b. Recontact

Twenty-three of the 58 forms mention some form of recontact for clinical purposes (Table 4). Within this group, there was again considerable variation regarding who will initiate recontact in light of any new information (Table 4). Forms commonly indicated that the laboratory will either recontact the clinician (8 forms), or the patient (8 forms), or they recommended that the patient should recontact the clinician in order to check if there have been any changes to their results (6 forms). One form stated that the clinician should contact the laboratory and none of the forms suggested that the patient should contact the laboratory directly. Only four of the forms sought consent to recontact patients for clinical purposes.

Discussion

Our analysis of 58 forms used for WGS, WES, or large NGS panels shows considerable variation in policies between laboratories/clinics in the reporting of VUS, as well as how they address reinterpretation of variants, and patient recontact.

Variants of uncertain significance

Of note, one-third of the forms in our study did not mention VUS. In those that did, we identified that there was some subtle variation in the terms used to refer to VUS. While most varied in their use of the terms “uncertain” versus “unclear” and the presence or absence of “clinical”, four of the forms referred to VUS as “results”, rather than variants. In general, whether a VUS is named as uncertain or unclear may not make much difference to how they are explained to patients. However, labeling a VUS as a “result” may give the wrong impression to both the clinician and the patient that the identification of this variant carries with it greater certainty or clinical significance than is warranted. This finding is particularly troubling in the context of concerns raised by laboratory personnel that health professionals might over-interpret the significance of VUS if they are reported to clinicians and/or included in the medical file [5].

There was also variation in whether explicit definitions or explanations of the term VUS (or related terminology) were provided. Roughly half of the forms in which VUS were mentioned provided some description as to what a VUS is. While in most cases the definition was explicit where the description was linked to the term used, in some cases this was less explicit or a description alone was used. The concept of a VUS may be difficult for patients (and also clinicians) to fully appreciate [20]. One could argue that it is implicit within the doctor-patient relationship that the clinician will make judgments about what is in the patients’ best interests and therefore describing a VUS to the patient on the consent form may not be necessary. However, it might be confusing to patients why a finding that is not a definitive result would be listed on a report, particularly if they ask for a copy. Listing on the consent form that a VUS is a possible outcome of the test, and providing a description of the term which clearly states that this is not a causative result, may help alleviate some of this confusion.

While there is no specific guidance provided by professional bodies as to whether VUS should be reported, several guidelines suggest that laboratories should have well-established policies addressing VUS, which need to be made clear to referring clinicians [7,8,9,10]. One way to inform clinicians of these policies, outside of continuing education or distinct information pamphlets, is by providing information or policies in requisition and/or consent forms. Yet, only approximately one-third of the forms in our study explicitly stated that VUS would be reported. Most forms either did not mentioned VUS at all or did not explicitly state their reporting policies for this type of finding. Also, in many cases, it was difficult to assess which VUS would be reported as most forms did not specify their reporting criteria. Of those that did, they would generally report VUS when they were thought to be related to the condition for which testing was sought, which is in line with practices reported by laboratory personnel that do report VUS [5]. One could argue that providing too much detail regarding reporting policies should be avoided in order to simplify often already lengthy and complicated consent forms [21, 22]. However, given that reporting practices seem to vary depending on the laboratory [5], it is important that the laboratory policy is made clear to the referring clinician so that both they, and their patients, are aware of whether these types of findings will be returned. Interestingly, interviews with genetic counsellors and research coordinators have identified that although the potential results of sequencing are often a main focus of genetic counselling sessions for WES and WGS, uncertainty of results is an aspect which they felt is likely to be misunderstood by patients/research participants [23].

Reinterpretation and recontact

As the use of NGS for both research and clinical purposes increases, and variants that are identified are shared on accessible databases, the status of previously unclassifiable variants is likely to change. In fact, evidence is now mounting to suggest that reanalyzing existing exome data increases the diagnostic yield, even as soon as 12 months after the initial analysis [24,25,26]. A currently unresolved 2016 lawsuit, Athena vs Williams, is testing the legalities of this area. In this case, the genetic testing company is being sued for alleged negligence based on their original classification of a variant as a VUS, which was later reclassified by them to be “pathogenic”, meaning that the variant was thought to affect function [27]. Regardless of the outcome, it is important for laboratories, clinicians, and patients to all be aware of their own rights and responsibilities in relation to both the reinterpretation of variants and the recontact of patients in response to changes in variant reclassification.

In relation to data reinterpretation, a number of professional guidelines have proposed that there is no duty for laboratories to reanalyze sequence data in response to changes in variant databases [7, 8]. Yet, there have been suggestions that it might be good practice for a laboratory to reissue a report if a variant is reclassified [6, 8, 12, 13]. Given the lack of consensus on the issue, perhaps more important is that patients are informed whether or not variant reinterpretation may take place. Yet our study showed that only around one-third of forms explicitly stated that reinterpretation of variants for clinical purposes may occur, and a large proportion did not even mention reinterpretation. Some forms suggested that variants might be reclassified or that more information may come to light in the future, without being more explicit as to the process involved. This suggests that many of the forms we identified are not conforming with the minimum list of information for inclusion suggested by Ayuso et al. (which was developed based on review of guidelines for genetic studies and proposed that consent forms should list policies for, among other aspects, reinterpreting results), or recommendations by the CCMG on this point [7, 15].

Less than half of the forms mention recontact for clinical purposes (as opposed to research purposes), which corresponds with a study by Fowler et al. which analyzed consent forms from 18 laboratories in which only half of the forms they analyzed discussed the possibility for recontact if reinterpretation of the results led to new information [16]. This again may not be in line with suggestions that recontact should be included as one of the elements on consent forms for high-throughput genomic sequencing [15]. As far as we are aware, no legal system has explicitly endorsed a legal responsibility for healthcare professionals to recontact patients once the care relationship has finished. Although legal systems have approaches to deal with medical negligence and medical faults, it seems unlikely that those would apply in this context [28]. In our study, of those forms that did mention recontact, we identified considerable variation as to whether the form nominated the laboratory, the clinician, or the patient as responsible for initiating recontact (although not all forms described these). Interestingly, there were a proportion of forms that indicated that the laboratory/clinic would recontact the patient in response to new information. This may be ineffective if the patient has changed their contact details since their initial testing, but also inappropriate unless the laboratory/clinic also plans to provide the patient with genetic counselling to help them understand the results. This finding of variation in policies supports those of a study of clinical genetic services in the UK which used surveys with healthcare professionals, and interviews with both laboratory specialists and healthcare professionals, to show that practices relating to recontact of patients in response to new genetic information was both very variable and unsystematic across the board [12, 13]. Both these studies, and interviews with patients, have flagged the confusion around the delineation of responsibility for initiating recontact as a serious challenge and a major barrier to the harmonization of practices [12,13,14]. In addition, systematic review of the literature relating to recontact has led to calls for professional consensus and development of guidelines [29]. In response to these findings, a “joint venture” model has been proposed which would involve the responsibility for recontact being shared between the healthcare professional and the patient [14]. Although this would circumvent issues related to patients being lost to follow up which may occur if reinterpretation is initiated by the laboratory, the allocation of responsibility between the patient and the healthcare professional using this model may remain unclear [14]. Indeed, although most of the patients/parents interviewed in the UK study favored this “joint venture” model, because they felt allowing the responsibility for recontact to rest solely with them could lead to harm, some participants also acknowledged that any such system working would require both better infrastructure, and better communication between healthcare professionals and patients [14]. In addition, although harmonization in practices and adoption of this type of model might be desirable in the UK, whether this is appropriate more broadly requires further consideration.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to systematically identify and analyze consent forms for high-throughput diagnostic NGS in relation to what they state regarding policies for reporting VUS, variant reinterpretation, and patient recontact, who should initiate this reinterpretation, and how recontact might take place. Given our strategy of including consent forms predominantly identified through online searches, and only those in English, our data set is not designed to be representative of all consent forms being used for diagnostic high-throughput sequencing. Our search strategy also meant that any supplementary information located in a separate file, such as a brochure, would not have been included. While providing additional information can be meaningful and useful to those seeking it, indeed, there is a risk that many (potentially most) will not read this information on their own. We would suggest that for now, given current consent practices, it makes more sense for the information and consent form to be in one document. However, importantly, the form should have a summary page which contains all of the main points in brief, any patient choice options, and the place for the patient’s signature. In addition, we cannot extrapolate how these forms are being used by clinicians during the informed consent process with their patients. Reports of genetic counsellors and research coordinators by Bernhardt et al. suggest that they tend to adjust the content of counselling sessions, focusing less on “standard” elements of informed consent and tailoring sessions to a given patient/research participant [23]. This often results in the genetic counsellors/researchers placing more attention on issues which are likely to be misunderstood by patients, such as uncertainty of the results. Our knowledge in the field would benefit from recorded consultations, or interviews with clinicians to explore the topics of VUS and recontact further. Despite this, our analysis provides important insights into the variation in how VUS and recontact are addressed in forms used both as supporting tools to guide informed consent sessions, and to document patient consent. Based on these findings, we have provided some suggestions for ethically appropriate inclusion of policies for reporting VUS, reinterpretation, and recontact on consent forms in Table 5. Should genomic sequencing become offered increasingly in the primary care setting, primary care physicians may need to rely more on the information included in consent forms than clinicians who are thoroughly trained in genetics. While the jury is still out as to whether individual laboratories should retain the ability to determine their own reporting practices regarding VUS, or whether we should be aiming for harmonization of practices, it is important that the policy is made clear to the clinician and patient. Whether the consent form is the best place for detailed descriptions of reporting policies also requires further consideration.

We identified very variable policies regarding the reinterpretation of variants, and also who is deemed responsible for the initiation of recontact. This is problematic because diffused responsibility has the potential to lead to lack of action, which could mean a missed opportunity for a patient and/or family member to receive a diagnosis in response to updates in variant classification. This is particularly challenging for patients not receiving ongoing care. More work is required to determine with whom this responsibility should rest, and how recontact can be implemented into the infrastructure of existing healthcare systems. Regardless of the model decided upon, it is important that the roles and responsibilities of the laboratory, clinician, and patient are clear to all parties. The consent form seems like an appropriate place for these to be outlined to ensure everyone is aware of the process and to allow for a conversation with the patient to be initiated by the clinician during the informed consent process. Of course, there are some countries (including Belgium, among others), where written consent for clinical genetic testing is not legally obligatory. Therefore, it is also important to incorporate-specific training for health professionals who are likely to be ordering genomic sequencing for their patients in order to equip them with the knowledge and skills to undertake the consent process adequately. Development of a template consent form that these health professionals could use as a guide for such situations would also be warranted.

References

Bertier G, Senecal K, Borry P, Vears DF. Unsolved challenges in pediatric whole-exome sequencing: a literature analysis. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2017;54:134–42.

Ream MA, Mikati MA. Clinical utility of genetic testing in pediatric drug-resistant epilepsy: a pilot study. Epilepsy Behav. 2014;37:241–8.

Belkadi A, Bolze A, Itan Y, et al. Whole-genome sequencing is more powerful than whole-exome sequencing for detecting exome variants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:5473–8.

Atwal PS, Brennan ML, Cox R, et al. Clinical whole-exome sequencing: are we there yet? Genet Med. 2014;16:717–9.

Vears DF, Senecal K, Borry P. Reporting practices for variants of uncertain significance from next generation sequencing technologies. Eur J Med Genet. 2017;60:553–8.

Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405–24.

Boycott K, Hartley T, Adam S, et al. The clinical application of genome-wide sequencing for monogenic diseases in Canada: Position Statement of the Canadian College of Medical Geneticists. J Med Genet. 2015;52:431–7.

Matthijs G, Souche E, Alders M, et al. Guidelines for diagnostic next-generation sequencing. Eur J Hum Genet. 2016;24:1515.

Rehm HL, Bale SJ, Bayrak-Toydemir P, et al. ACMG clinical laboratory standards for next-generation sequencing. Genet Med. 2013;15:733–47.

van El CG, Cornel MC, Borry P, et al. Whole-genome sequencing in health care: recommendations of the European Society of Human Genetics. Eur J Hum Genet. 2013;21(suppl. 1):S1–S5.

Jamal SM, Yu JH, Chong JX, et al. Practices and policies of clinical exome sequencing providers: analysis and implications. Am J Med Genet A. 2013;161A:935–50.

Carrieri D, Dheensa S, Doheny S, et al. Recontacting in clinical practice: an investigation of the views of healthcare professionals and clinical scientists in the United Kingdom. Eur J Hum Genet. 2017;25:275–9.

Carrieri D, Lucassen AM, Clarke AJ, et al. Recontact in clinical practice: a survey of clinical genetics services in the United Kingdom. Genet Med. 2016;18:876–81.

Dheensa S, Carrieri D, Kelly S, et al. A ‘joint venture’ model of recontacting in clinical genomics: challenges for responsible implementation. Eur J Med Genet. 2017;60:403–9.

Ayuso C, Millán JM, Mancheno M, Dal-Ré R. Informed consent for whole-genome sequencing studies in the clinical setting Proposed recommendations on essential content and process. Eur J Human Genet. 2013;21:1054–9.

Fowler SA, Saunders CJ, Hoffman MA. Variation among consent forms for clinical whole exome sequencing. J Genet Couns. 2017; Epub ahead of print. 27(1):104-114.

Schamber L. Time-line interviews and inductive content analysis: their effectiveness for exploring cognitive behaviors. J Am Soc Inf Sci. 2000;51:734–44.

Downe-Wamboldt B. Content analysis: method, applications, and issues. Health Care Women Int. 1992;13:313–21.

Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24:105–12.

Solomon I, Harrington E, Hooker G, et al. Lynch Syndrome Limbo: patient understanding of variants of uncertain significance. J Genet Couns. 2017;26:866–77.

Beskow LM, Friedman JY, Hardy NC, Lin L, Weinfurt KP. Developing a simplified consent form for biobanking. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e13302.

Beardsley E, Jefford M, Mileshkin L. Longer consent forms for clinical trials compromise patient understanding: so why are they lengthening? J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:e13–4.

Bernhardt BA, Roche MI, Perry DL, Scollon SR, Tomlinson AN, Skinner D. Experiences with obtaining informed consent for genomic sequencing. Am J Med Genet A. 2015;167a:2635–46.

Wenger AM, Guturu H, Bernstein JA, Bejerano G. Systematic reanalysis of clinical exome data yields additional diagnoses: implications for providers. Genet Med. 2017;19:209–14.

Wright CF, McRae JF, Clayton S, et al. Making new genetic diagnoses with old data: iterative reanalysis and reporting from genome-wide data in 1,133 families with developmental disorders. Genet Med. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2017.246.

Ewans LJ, Schofield D, Shrestha R, et al. Whole-exome sequencing reanalysis at 12 months boosts diagnosis and is cost-effective when applied early in Mendelian disorders. Genet Med. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2018.39.

Thorogood A, Cook-Deegan R, Knoppers BM. Public variant databases: liability? Genet Med. 2017;19:838–41.

Carrieri D, Jackson L, Howard HC, et al. Recontacting patients in clinical genetics services: recommendations of the European Society of Human Genetics. Eur J Hum Genet. 2018. In press.

Otten E, Plantinga M, Birnie E, et al. Is there a duty to recontact in light of new genetic technologies? A systematic review of the literature. Genet Med. 2015;17:668–78.

Acknowledgements

D.F.V. is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow of the Research Foundation - Flanders (FWO-Vlaanderen). E.N. has been supported by Erasmus Plus Joint International PhD Programme in Law, Science and Technology Fellowship. This work was facilitated by the COST Action IS1303 ‘Citizen’s Health through public-private Initiatives: Public health, Market and Ethical perspectives’, supported by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology) (http://www.cost.eu). Part of this work has been supported by the SIENNA project, (under grant agreement No 741716) and the BBMRI-ERIC.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vears, D.F., Niemiec, E., Howard, H.C. et al. Analysis of VUS reporting, variant reinterpretation and recontact policies in clinical genomic sequencing consent forms. Eur J Hum Genet 26, 1743–1751 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-018-0239-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-018-0239-7

This article is cited by

-

Whole genome sequencing in clinical practice

BMC Medical Genomics (2024)

-

Systematic reanalysis of genomic data by diagnostic laboratories: a scoping review of ethical, economic, legal and (psycho)social implications

European Journal of Human Genetics (2024)

-

The Need to Standardize the Reanalysis of Genomic Sequencing Results: Findings from Interviews with Underserved Families in Genomic Research

Journal of Bioethical Inquiry (2023)

-

Diagnostic yield of next-generation sequencing in 87 families with neurodevelopmental disorders

Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases (2022)

-

Recontacting in medical genetics: the implications of a broadening knowledge base

Human Genetics (2022)