Abstract

In this study, we evaluate the effect of education and deliberation on the willingness of members of the public to donate tissue to biobank research and on their attitudes regarding various biobank consent policies. Participants were randomly assigned to a democratic deliberation (DD) group, an education group that received only written materials, and a control group. Participants completed a survey before the deliberation and two surveys post-deliberation: one on (or just after) the deliberation day, and one 4 weeks later. Subjects were asked to rate 5 biobank consent policies as acceptable (or not) and to identify the best and worst policies. Analyses compared acceptability of different policy options and changes in attitudes across the three groups. After deliberation, subjects in the DD group were less likely to find broad consent (defined here as consent for the use of donations in an unspecified range of future research studies, subject to content and process restrictions) and study-by-study consent acceptable. The DD group was also significantly less likely to endorse broad consent as the best policy (OR = 0.34), and more likely to prefer alternative consent options. These results raise ethical challenges to the current widespread reliance on broad consent in biobank research, but do not support study-by-study consent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Research biobanks have become critical repositories of biological, demographic, and clinical data for medical research. By providing centralized and curated health data, biobanks enable researchers to carry out more efficient studies over larger populations, which may lead to breakthroughs in scientific understanding of human disease, benefiting society through advances in diagnosis, prevention and treatment of disease. Fundamental to biobank success is the donation of biological specimens and associated data.

Permission for the research uses of specimens and related clinical or other information collected from patients and volunteers is commonly obtained using a form of ‘broad’ consent in which a donor grants permission for ‘an unspecified range of future research subject to a few content and/or process restrictions.’ [1] Such a consent is thought necessary because the scope of possible research uses is unpredictable, it is impossible to list them in any practical consent, and any attempt to list them exhaustively would bar potentially very important research not listed. For these reasons, the OECD Guidelines on Human Biobanks and Genetic Research Databases permit broad consent, stating that ‘Where authorised by applicable law and the appropriate authorities, the operators of the HBGRD could consider obtaining a consent that will permit human biological specimens and/or data to be used to address unforeseen research questions’, specifying that ‘Participants should be fully informed of the breadth of such consent and there should be additional safeguards in place to ensure that participants are protected.’ In the United States, broad consents are permitted under guidance from the Secretary’s Advisory Committee for Human Research Protections (SACHRP) [2].

Such consents are widely used, and vary significantly in the amount and kinds of information they provide to prospective donors. Some are less than a page long, and even when longer may provide limited information about the range of possible future research uses [3,4,5].

Although such open-ended broad consents give prospective donors control over whether their specimens and data will be used in research, they rarely offer any control over what kinds of research that will be. Yet we know that people often care about the ways their materials might later be used, and may object to certain kinds of research on moral, religious or cultural grounds [6]. Because such uses are unlikely to directly affect the donor, we call these the ‘non-welfare interests’ (NWIs) of donors, and we measured their significance using a national survey fielded in the U.S. in 2014. Our analyses revealed, among other things, that when participants were presented with research scenarios with potential NWI concerns, there were significant and sometimes substantial declines in the willingness to give open-ended broad consent [7]. We also found that for >70% of respondents, willingness to give broad consent was adversely affected by at least one scenario and that lower levels of trust in biomedical research was a strong predictor of this effect [8]. Further, when our respondents were asked to evaluate alternative forms of consent, substantial minorities found both broad and ‘real-time’ specific consent (in which the biobank asks for donor consent for each specific project) to be ‘unacceptable’ policies (43.6% and 43%, respectively) or to be the ‘worst’ policies (37.8%, 45%) among five options [9].

Some biobanks may address their donors’ NWIs in other ways, subsequent to the consent, such as ethical oversight of proposed research, or representation of the donor community in biobank governance. Our findings focus on the question of whether the NWIs of donors can be accommodated using alternative forms of consent.

Our national survey, while informative, suffers from limitations common to the use of surveys to assess public attitudes about complex ethical problems. Education on the issues, for example, was very limited. Survey respondents were provided with some background information, but the demands of questionnaire design restrict the amount of information that can be shared. Furthermore, our national respondents had no opportunity to deepen their perspectives by engaging in thoughtful deliberation with others.

These concerns led us to develop a series of ‘democratic deliberations’ (DD) where the informed voices of the general public are solicited for the purpose of creating policy, using a process of in-depth education and peer deliberation. DD has been used to investigate a range of bioethical issues such as flu pandemic resource allocation, surrogate consent for dementia research, cancer screening, and the return of genomic test results [10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. Reports from these deliberative exercises show that the opportunity to be educated and to engage with others in discussions about complex issues often shifts policy preferences [11, 16].

Materials and methods

The theoretical basis and design of our DD project—randomized, experimental design to optimize internal validity—was based on a previous DD study on surrogate consent for dementia research [10, 11]. The current study was deemed exempt from federal regulations by the University of Michigan and Michigan State University.

Recruitment

Members of the public were recruited by the Survey Research Center (SRC) of the Institute for Social Research at the University of Michigan using address-based sampling. We began with a small pilot session, followed by two larger deliberations. Recruitment mailings were sent to addresses within a 60-mile radius of Ann Arbor, MI and East Lansing, MI (the session locations). Individuals who responded to the initial recruitment mailing (by web, postcard, or phone) were then called by SRC to be screened and given additional details about the study. In order to supplement initially low recruitment response rates for our pilot session, a minority of pilot participants (38 out of 84) were recruited through the UM Health Research (formerly UM Clinical Studies) website (umhealthresearch.org)—an online portal for University of Michigan researchers to recruit human subjects [17]. For the two subsequent and larger sessions, initial SRC mailings were increased and recruitment goals were achieved with address-based sampling only. Participants were required to be at least 21 years old and be available on the date of an upcoming DD session. In an attempt to reach levels more representative of the national population, Hispanics were oversampled.

SRC sent 19 680 mailings, which resulted in 1128 responses. Of 590 eligible SRC recruits and 38 UM Health Research pilot session recruits (628 total), 596 (95%) completed the baseline survey. After completing the baseline survey, participants were randomized into one of three groups (Control, Education, or DD group) at a 3:3:3.7 ratio (based on previous DD studies and pilot attendance rates). As described in greater detail below, the DD group attended an all-day DD session, including expert presentations and small group deliberations. The DD group received copies (either by mail or email) of the annotated expert presentations a few weeks before the session day. The education group received these same materials but did not attend the DD session. The control group received the surveys only (see Supplemental Figure S1 for the recruitment flow chart.)

Surveys

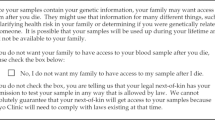

The survey administered to participants was the same one used in our previous national study [9]. It starts with a brief description of a fictional biobank and an explanation of the process of donating to a biobank. In keeping with current definitions of broad consent [1], the description of the biobank includes the assurance that ‘Before a researcher can use your biobank sample, a committee must review the study. This committee will make sure the study is well designed, protects your privacy, and will help society.’ After these descriptions, participants are asked six true/false questions about the fictional biobank to evaluate their understanding (the average number of correct responses at baseline, including participants from all three groups, was 5.63 out of a maximum of 6). The survey then uses a 6-point Likert scale—from ‘Strongly Disagree’ to ‘Strongly Agree’—to assess participant willingness to donate to the biobank using broad consent. After this initial assessment, participants are presented with seven hypothetical ‘non-welfare interest’ (NWI) research scenarios—that is, research scenarios that could be morally, religiously, or culturally concerning to a donor without directly affecting their well-being, such as research to find better and safer abortion methods or that might result in profits for commercial companies. For each NWI research scenario, respondents were asked again how willing they would be (using the same 6-point Likert scale) to donate to a biobank using broad consent, ‘even if’ their samples might be used in the scenario described. Each of these scenarios included potentially negative and positive aspects. For example, the commercial companies’ scenario read ‘researchers might use biobank donations to develop patents and earn profits for commercial companies. Most new drugs used to treat or prevent disease come from commercial companies.’

In addition to the questions about participants’ willingness to donate, participants were asked about their biobank consent policy preferences. They were given a brief description, including the potential positive and negative effects, of five different consent policies (Table 1). These included the unqualified broad consent originally presented to them, three variations on that broad consent, and study-by-study consent. Participants were then asked to identify policies that are ‘acceptable,’ the policy that is ‘best,’ and the policy that is ‘worst.’ It is important to note that our description of the biobank included the assurance of ongoing review, allowing us to assess participants’ attitudes toward different types of consent, all of which are variations on the types of consent permitted under regulations and guidelines [18,19,20].

In addition, we collected a number of attitudinal and socio-demographic variables. These include a measure of ‘residual privacy concern,’—how worried respondents would be that someone not authorized might see their private information, even after being told a ‘committee will make sure the study…protects your privacy’ (on a 5-point scale from ‘Not worried at all’ to ‘Very Worried’)—as well as their level of trust in biomedical research, measured using the Research Attitudes Questionnaire (RAQ) [21].

Depending on their preference, DD study participants received surveys either by mail or online via an email link (Qualtrics survey platform, www.qualtrics.com). Identical surveys were administered to each participant at three time points, regardless of group assignment. Survey 1 was administered 1–2 months prior to the DD session (as participants were recruited). Survey 2 was sent out around the time of the DD session (with DD attendees completing the survey in person at the end of the session). The education and DD groups were provided with copies of the annotated DD expert presentations to be reviewed prior to completing Survey 2 (education group) or prior to the DD session day (DD group). Survey 3 was sent out to all participants one month after the DD session.

DD sessions

One pilot DD session (Ann Arbor, MI) and two full DD sessions (Ann Arbor and East Lansing, MI) were conducted in 2015. DD group attendees were assigned to small groups of 6–8 participants with a trained facilitator. Small group assignments were randomly allocated, except for post-randomization modifications to ensure gender and ethnic diversity at each table. All facilitators attended at least one 2 h training session conducted by members of the study team with expertise in qualitative research and democratic deliberation, similar to training sessions used in previous studies [16, 22]. A detailed sequence of events during the DD day is given in Supplemental Table S1.

DD materials

We developed three plenary presentations to provide background for two deliberations by participants. Each presentation included time for comments and questions from participants. The first presentation, ‘What is a Biobank and how is it used in Medical Research?’ describes how biobanks work, how samples are collected and used, the risks and benefits of biobank research, how donor identity is protected, and the role of Institutional Review Boards (IRBs). The second presentation, ‘Ethical Issues in Biobank Research,’ describes the history of human research ethics, well-known past abuses (such as the Nazi experiments and the Tuskegee syphilis study), the resulting human subject protections, how these apply (or do not apply) to biobank research, and reasons both for and against consideration of possible non-welfare interests. A third plenary presentation provided an overview of five consent policy options, including the potential pros and cons of each of the policies.

DD evaluation

At Survey 2, DD session attendees were asked to evaluate the DD session day, with 11 questions on a 10-point scale (from ‘Not at all/Not helpful at all’ to ‘Very Much/Extremely helpful’). The education group was asked how much of the educational materials they were able to review (from ‘None’ to ‘All’) and to evaluate the educational materials.

Analyses

For willingness to consent, the 6-point Likert scale was dichotomized into willing and unwilling. We examined baseline demographic characteristics and attitudes across the three arms using chi-square tests for dichotomous variables and ANOVA for continuous variables. All analyses were conducted using intent-to-treat (ITT) approach where study enrollees were included in the groups to which they were randomly assigned, regardless of whether they adhered to their intervention (i.e., reviewed the education materials or participated in the DD sessions). ITT is the standard approach for analyzing randomized trials because it preserves randomization and thus maintains prognostic balance at baseline, providing an unbiased estimate of the effect of the intervention [23].

To test for the effect of deliberation and education on willingness to provide consent, the acceptability of different consent policies, and the consent policy evaluated as best and worst, we fit a hierarchical logistic regression model. In this model, responses at all three survey times from all three groups were the dependent variable, participants were included as random intercepts to account for within-person correlation, and the predictor variables included dummies for Survey 2 and Survey 3, for the DD group and the Education group, and for the four interactions of the two survey time dummies and the two study arm dummies. The use of a hierarchical logistic regression model allowed us to include all available response data, including data from cases where responses from Survey 2, Survey 3 or both were missing. The parameter estimates of the interaction terms provided odds ratio (OR) estimates as summary measures comparing the dichotomized responses between each intervention group and the control group at each survey time. For example, an OR of “willingness to donate” that is significantly less than 1.0 for the DD as compared to the control group at Survey 3 can be interpreted as significantly lower willingness in the DD group relative to control group at Survey 3, after adjusting for trends in willingness across surveys.

All analyses were conducted using Stata 14.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Results

Baseline demographic and attitudinal variables are included in Supplemental Table S2. There were no significant differences across the three arms.

Evaluation of the DD sessions and educational materials

DD session attendees rated their experiences very positively (ranging from 8.9 to 9.8 out of 10) (Table 2). The participants felt strongly that the process was fair and that their opinions were respected. Attendees at the DD session reported a greater impact of the intervention on their understanding of and opinions than did those who received educational materials alone.

Changes in willingness to donate

Across all three groups, 88% of participants were initially willing to donate using broad consent at Survey 1. Looking at within-group changes in willingness to donate across the three surveys shows a substantial decrease in willingness to donate for the DD group at Survey 2 and 3. However, when compared to the change in willingness in the control group using a hierarchal logistic regression model, there was no significant effect of deliberation. These findings were similar to the education group, which had a significant within group decrease at Survey 2 only, but was not significant when compared to the control group change (Table 3).

Consent policy preferences

Table 3 also summarizes changes in the acceptability of each of the five different biobank policies across the three study groups. Compared to the control group, there was a significant decrease between Survey 1 and 3 in the acceptability of both broad (OR = 0.35) and study-by-study (OR = 0.43) consent in the DD group but not in the education group.

Participants were also asked to select the worst and the best policy options. For the entire study sample (all three groups combined) at baseline (i.e., survey 1), 72% of participants identified study-by-study consent as the worst policy, and 18% found broad consent to be the worst policy; between 1 and 4% identified the remaining policies as worst. Broad consent was named best by 36% of all participants, and 5% identified study-by-study consent as best.

Deliberation reduced the number of participants identifying broad consent as the best consent policy. Figure 1 shows the rank of each policy according to the percentage of those in the DD group who identified that policy as best in each of the three surveys (see Table S3 also). When compared to the control group at Survey 2, DD group participants demonstrated greater approval of ‘broad consent combined with limits’ (OR = 2.62) and were less enthusiastic about “broad consent with an option to withdraw” (OR = 0.39). Comparing control and DD groups at Survey 3, DD participants were less likely to choose broad consent as best (OR = 0.34), and more likely to choose ‘broad consent combined with a caution’ (OR = 3.89). Changes in the preference for the best consent policy did not differ between the education and control groups. Study-by-study consent was consistently judged as the worst policy by a majority of participants in all three arms and across all three surveys. Neither deliberation nor education significantly affected identifying a policy as the worst consent policy compared with control in either Survey 2 or 3 (Supplemental Table S4).

Trust and concerns about privacy

Table 3 shows that there are no substantive differences among the groups in scores for the Research Attitudes Questionnaire (range 11 - 66, higher scores = greater levels of trust) and residual privacy concerns (5-point scale from 1 = ‘Not worried at all’ to 5 = ‘Very worried’). RAQ scores hovered around 50 for all three groups and across all three time-points (range = 49.4 to 51.7); scores for residual privacy concerns ranged from 1.96 to 2.16 across all three groups and time points.

Discussion

This study examines how participation in a democratic deliberation—involving both expert education and peer deliberation—affects the views of the public on complex questions related to consent for the use of donations to a biobank. In particular, we look at how information and deliberation about donors’ NWIs alter willingness to donate to biobanks and views about various consent policy options. In our earlier work [7,8,9], we measured public attitudes about these issues via a cross-sectional national survey; this phase of our research used an experimental design to assess the potential impact of education and deliberation on those attitudes.

It is notable that even after deliberation on the ethical challenges that NWIs present for the use of broad consent, a large majority of deliberators were still willing to give an unqualified broad consent, and still found a broad consent policy ‘acceptable.’ This was despite statistically significant reductions, after deliberation, in the acceptability of a broad consent policy and in their rating of broad consent as the ‘best’ option. It is also notable that after deliberation, the DD group was more inclined to select consent options that take into consideration the possibility that a donor’s non-welfare interests might conflict with future research using their donation.

Our previous survey of a nationally representative sample showed that trust in science (as measured by the RAQ) and concerns about privacy were both strongly associated with willingness to give broad consent and with policy preferences [8, 9]. Thus, we wondered if the effects of deliberation we discovered were related to changes in level of trust or concern with privacy. We found, however, that scores on the RAQ and privacy concerns remained stable across the three surveys for all groups, suggesting that the changes we found are not because deliberation reduced trust or increased privacy concerns, but instead were due to increased awareness and concern about NWIs. In this regard, the significant decline in support for study-by-study consent among deliberators suggests that there could be concerning features of that policy that became more apparent (e.g., burden of re-contact) upon deliberation, despite the increased control over future research uses that it offers [24]. Indeed, study-by-study consent was most frequently selected as the worst policy option in all groups across all time points.

The most important limitation of our study is a result of the very intensive nature of the experiment, which likely generated some degree of selection bias among those who agreed to participate. At baseline participants in this study already had a significantly higher level of trust than the national sample of our previous cross-sectional survey (RAQ mean 51.2 vs. 44.0; p < 0.001 using independent samples t-test) and a significantly lower concern about privacy (residual privacy concern mean 2.06 vs. 2.85; p < 0.001). This means that we should be cautious in generalizing our results to a population that may be less trusting and/or more concerned about privacy. It is possible then that the current study underestimates the impact education and deliberation would have among those whose attitudes are already less supportive of broad consent. Indeed other studies suggest that once people merely become aware of other consent options, they become less accepting of broad consent [25, 26]. Furthermore, although there is some loss in generalizability regarding the point estimates (of proportions who support a given policy, for example), our experimental design using deliberative methods yields important data on how fully informed and considered moral opinions of citizens might look in comparison to opinions based on cursory information provided in typical cross-sectional surveys.

Our use of Intention to Treat (ITT) analysis may underestimate the impact of our educational and deliberative interventions. ITT is used to avoid bias from crossover effects by comparing subjects according to the intervention arm originally assigned, regardless of whether they remained in that arm. If a subset of participants in an intervention group fail to receive the intervention as a result of dropping out, the estimate of the effect could be inflated. Those who do not drop out may be different from dropouts—e.g., healthier or, in our case, more motivated. Removing dropouts from the arm they are assigned to typically strengthens the effect of the intervention. In order to avoid an artificial increase in the effect of our intervention, we chose to adhere to the preferred, but more conservative, ITT approach in our analysis.

Our ability to generalize from this democratic deliberation is also limited by the fact that our survey data do not allow us to tease out the effects of different elements of the deliberation (e.g., the expert presentations and the peer deliberation) or to examine the considerations that drove shifts in the opinions of participants. We know that the DD participants thought the process was fair and informative, and that it influenced their understanding and opinions. In the next stage of this research we will be conducting a qualitative analysis of the DD deliberations to assess the impact of different elements of the deliberative process and to identify the perspectives, goals, and values that directly affected participant consent policy preferences. A richer understanding of these dimensions of deliberation will allow us to target the elements of the consent process that need to be improved.

However, it is clear from our findings that the more people learn about the open-ended nature of biobank research and the future research projects that makes possible, the more cautious they become, and the more skeptical about relying on unqualified broad consent. NWIs matter to people, reduce their willingness to donate to biobanks using broad consent, and increase the attractiveness of consent options that offer more control over risk to donors’ NWIs.

Our results point to the need to supplement our current reliance on broad consent with measures that respect and accommodate NWIs. These measures may include some variants of the middle-of-the-road consent options that many of our participants preferred, such as broad consent with a caution. An example of this approach is the broad consent template recommended by SACHRP for use with identifiable specimens. That template includes a list of some types of biospecimen-based research that are known to concern some people (e.g., ‘Research that includes changing the genes in cells or putting human cells into animals’), followed by a warning that the donor’s specimen and data might be used ‘in a research project to which you might not agree, if you were asked specifically about it.’

With the exception of study-by-study consent, however, any consent process is limited in its capacity to accommodate NWIs, because it cannot adapt to new research questions and methods, or to the changing values and preferences of donors. Given these factors, it may be advisable to develop an alternative to current consenting practices that more appropriately address the unique context of biobanking [27,28,29,30,31].

Consent is a vital and necessary condition for accommodating NWIs, giving individuals and biobanks the opportunity to address the concerns of those whose specimens are being used. Nevertheless, it is clear that consent cannot do all the work of satisfying donor concerns about the fate of their donations—as the Nuffield Council points out, consent by itself is a very thin expression of respect for donor autonomy [32].

In order to respect donors’ non-welfare interests, other steps need to be taken, both pre- and post-consent. Transparency is important, but we have learned that the kind of transparency offered by study-by-study consent is not desired by the public. Rather, there needs to be greater public transparency regarding the biobank’s mission and the specific projects it has supported in the past. In addition, as suggested by the WMA Declaration of Taipei, motivated donors should be able to get information about the ways their individual donations have been used [33], not so they can prospectively consent, but so they can judge for themselves whether they want their materials to remain in the biobank. Deliberative exercises can help the biobank identify concerns among its donor community that might be addressed by biobank governance and policy [30], and representatives of the donor community can be given meaningful roles in governance, such as the Community Values Advisory Board that helps oversee the uses of Michigan’s collection of neonatal bloodspots [34]. These complements to consent may add cost to the biobanking process, but respect for donors and the values they hold dear justify additional expense. The challenge for the biobanking community is to offer donors more control and more confidence that their concerns will be respected, without resorting to consent policies that will unnecessarily restrict research, policies donors clearly do not desire [35,36,37].

Disclaimer

The ideas and opinions expressed by S.K. in this paper are his own; they do not represent any position or policy of the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Health and Human Services, or the U.S. government

References

Grady C, Eckstein L, Berkman B, et al. Broad consent for research with biological samples: workshop conclusions. Am J Bioeth. 2015;15:34–42.

Attachment C - Recommendations for Broad Consent Guidance. Office for Human Research Protections, 2017. Available at https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/sachrp-committee/recommendations/attachment-c-august-2-2017/index.html

Mayo Clinic Biobank Consent Form. Mayo Clinic Biobank. Available at http://www.mayo.edu/research/documents/biobank-consent-formpdf/DOC-10027511. (accessed on 31 October 2017)

Consent Form: United Kingdom Biobank. United Kingdom Biobank. 2017.Available at http://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/Consent_form.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2017)

BioVU Consent Form. Vanderbilt University Medical Center. 2017. Available at https://victr.vanderbilt.edu/pub/biovu/?sid=220 (accessed on 31 October 2017)

Van Assche K, Gutwirth S, Sterckx S. Protecting dignitary interests of biobank research participants: lessons from havasupai tribe v Arizona board of regents. Law, Innov Technol. 2013;5:54–84.

Tomlinson T, De Vries R, Ryan K, Kim HM, Lehpamer N, Kim SY. Moral concerns and the willingness to donate to a research biobank. JAMA. 2015;313:417–9.

De Vries RG, Tomlinson T, Kim HM, et al. The moral concerns of biobank donors: the effect of non-welfare interests on willingness to donate. Life Sci Soc Policy. 2016;12:3.

De Vries RG, Tomlinson T, Kim HM, et al. Understanding the public’s reservations about broad consent and study-by-study consent for donations to a biobank: Results of a National Survey. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0159113.

De Vries R, Stanczyk A, Wall IF, Uhlmann R, Damschroder LJ, Kim SY. Assessing the quality of democratic deliberation: a case study of public deliberation on the ethics of surrogate consent for research. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70:1896–903.

Kim SY, Kim HM, Knopman DS, De Vries R, Damschroder L, Appelbaum PS. Effect of public deliberation on attitudes toward surrogate consent for dementia research. Neurology. 2011;77:2097–104.

McWhirter RE, Critchley CR, Nicol D, et al. Community engagement for big epidemiology: deliberative democracy as a tool. J Pers Med. 2014;4:459–74.

Rychetnik L, Carter SM, Abelson J, et al. Enhancing citizen engagement in cancer screening through deliberative democracy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:380–6.

Silva DS, Gibson JL, Robertson A, et al. Priority setting of ICU resources in an influenza pandemic: a qualitative study of the Canadian public’s perspectives. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:241.

Thomas R, Glasziou P, Rychetnik L, Mackenzie G, Gardiner R, Doust J. Deliberative democracy and cancer screening consent: a randomised control trial of the effect of a community jury on men’s knowledge about and intentions to participate in PSA screening. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e005691.

Gornick MC, Scherer AM, Sutton EJ, et al. Effect of public deliberation on attitudes toward return of secondary results in genomic sequencing. J Genet Couns. 2016;26:122–32.

Dwyer-White M, Doshi A, Hill M, Pienta KJ. Centralized research recruitment-evolving a local clinical research recruitment web application to better meet user needs. Clin Transl Sci. 2011;4:363–8.

OECD Guidelines on Human Biobanks and Genetic Research Databases (Section 4. 6). 2009. Available at https://www.oecd.org/sti/biotech/44054609.pdf

Strech D, Bein S, Brumhard M, et al. A template for broad consent in biobank research. Results and explanation of an evidence and consensus-based development process. Eur J Med Genet. 2016;59:295–309.

ISBER best practices for repositories: collection, storage, retrieval and distribution of biological materials for research (Section L2.200). 2012. Available at http://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.isber.org/resource/resmgr/Files/ISBER_Best_Practices_3rd_Edi.pdf

Rubright JD, Cary MS, Karlawish JH, Kim SY. Measuring how people view biomedical research: Reliability and validity analysis of the Research Attitudes Questionnaire. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2011;6:63–8.

Kim SY, Wall IF, Stanczyk A, De Vries R. Assessing the public’s views in research ethics controversies: deliberative democracy and bioethics as natural allies. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2009;4:3–16.

Fisher LD, Dixon DO, Herson J, Frankowski RK, Hearron MS, Peace KE. Intention to Treat in Clinical Trials. Statistical issues in drug research and development. New York: M. Dekker; 1989:331–50.

Simon CM, L’Heureux J, Murray JC, et al. Active choice but not too active: public perspectives on biobank consent models. Genet Med. 2011;13:821–31.

D’Abramo F, Schildmann J, Vollmann J. Research participants’ perceptions and views on consent for biobank research: a review of empirical data and ethical analysis. BMC Med Ethics. 2015;16:60.

Garrison NA, Sathe NA, Antommaria AH, et al. A systematic literature review of individuals’ perspectives on broad consent and data sharing in the United States. Genet Med. 2016;18:663–71.

Solomon S, Mongoven A. Extending the surrogacy analogy: applying the advance directive model to biobanks. Public Health Genom. 2015;18:1–10.

Mongoven AM, Solomon S. Biobanking: shifting the analogy from consent to surrogacy. Genet Med. 2012;14:183–8.

Grady C. Enduring and emerging challenges of informed consent. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:855–62.

Koenig BA. Have we asked too much of consent? Hastings Cent Rep. 2014;44:33–4.

Cargill SS. Biobanking and the abandonment of informed consent: an ethical imperative. Public Health Ethics. 2016;9:255–63.

Nuffield Council on Bioethics. The collection, linking and use of data in biomedical research and health care: ethical issues (Section 3. 12). 2015. Available at http://nuffieldbioethics.org/wp-content/uploads/Biological_and_health_data_web.pdf

WMA Declaration of Taipei On Ethical Considerations Regarding Health Databases and Biobanks (Principle 14). 2016. Available at https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-taipei-on-ethical-considerations-regarding-health-databases-and-biobanks/

Chrysler D, McGee H, Bach J, Goldman E, Jacobson PD. The Michigan BioTrust for Health: using dried bloodspots for research to benefit the community while respecting the individual. J Law Med Ethics. 2011;39(Suppl 1):98–101.

Garrett SB, Dohan D, Koenig BA. Linking broad consent to biobank governance: support from a deliberative public engagement in California. Am J Bioeth. 2015;15:56–7.

O’Doherty KC, Burgess MM, Edwards K, et al. From consent to institutions: designing adaptive governance for genomic biobanks. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73:367–74.

O’Doherty KC, Hawkins AK, Burgess MM. Involving citizens in the ethics of biobank research: informing institutional policy through structured public deliberation. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75:1604–11.

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by grant 1 R01 HG007172-01A1 from the National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health, USA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tomlinson, T., De Vries, R.G., Kim, H. et al. Effect of deliberation on the public’s attitudes toward consent policies for biobank research. Eur J Hum Genet 26, 176–185 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-017-0063-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-017-0063-5