Abstract

Background/objectives

Refeeding syndrome (RFS) can occur in severely malnourished or starved populations that are provided with rapid or unbalanced nutrition. International guidelines recommend a cautious approach for managing RFS risk (hypocaloric nutrition for 4–7 days), however emerging evidence supports a more assertive approach. This study aimed to describe nutritional management and RFS-related adverse outcomes in patients at risk of RFS receiving care after implementing updated guidelines reflecting emerging evidence.

Subjects/methods

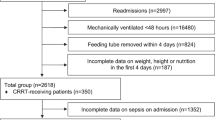

A retrospective cohort study of inpatients at risk of RFS during admission to a large metropolitan hospital in Queensland, Australia between November 2018 and April 2019 was conducted. Data were collected from medical records on nutritional management (provision of nutrition, electrolyte, and vitamin replacement) and outcomes (incidence of RFS, serum electrolyte decreases, hypo/hyperglycaemia, oedema, and organ function disturbance). Data were analysed descriptively; relationships between serum electrolyte decreases and nutrition management were explored using Fisher’s Exact tests.

Results

Of the 70 patients identified at risk of RFS (58.4 ± 16.8 years, 56% male, 94% malnourished), majority of participants received required supplementation prior to the commencement of nutrition (thiamine: 76%; micronutrients: 72–100%; multivitamin: 61%) and a standard initial nutrition management plan (79%; cautious: 13%; liberal: 8%). There were no cases of RFS. Four participants experienced RFS-related adverse outcomes (severe electrolyte decreases: n = 2, hypo/hyperglycaemia: n = 2); however, there was no differences in serum electrolyte decreases based on the nutrition management plan (initial: p = 0.912; goal: p = 0.688).

Conclusions

The implementation of more liberal RFS guidelines for the management of RFS risk appears to be safe. Further research examining liberalised refeeding protocols may be useful in updating international guidelines.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Friedli N, Stanga Z, Sobotka L, Culkin A, Kondrup J, Laviano A, et al. Revisiting the refeeding syndrome: Results of a systematic review. J Nutr. 2017;35:151–60.

Rio A, Whelan K, Goff L, Reidlinger DP, Smeeton N. Occurrence of refeeding syndrome in adults started on artificial nutrition support: prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2013;3:1–9.

Owers EL, Reeves AI, Ko SY, Ellis AK, Huxtable SL, Noble SA, et al. Rates of adult acute inpatients documented as at risk of refeeding syndrome by dietitians. Clin Nutr. 2015;34:134–9.

Boot WACR, Koekkoek RHK, Van Zanten RHA. Refeeding syndrome: relevance for the critically ill patient. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2018;24:235–40.

Matthews KL, Capra SM, Palmer MA. Throw caution to the wind: is refeeding syndrome really a cause of death in acute care? EJCN. 2018;72:93–8.

Wagstaff G. Dietetic practice in refeeding syndrome. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2011;24:505–15.

National Institute for Health and Care ExcellenceNational Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Nutrition support for adults: oral nutrition support, enteral tube feeding and parenteral nutrition. NICE; 2018. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg32/resources/nutrition-support-for-adults-oral-nutrition-support-enteral-tube-feeding-and-parenteral-nutrition-pdf-975383198917. Accessed 22 Feb 2006.

Matthews K, Hill J, Jeffrey S, Patterson S, Davis A, Ward W, et al. A higher-calorie refeeding protocol does not increase adverse outcomes in adult patients with eating disorders. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2018;118:1450–63.

Parker EK, Faruquie SS, Anderson G, Gomes L, Kennedy A, Wearne CM, et al. Higher caloric refeeding is safe in hospitalised adolescent patients with restrictive eating disorders. J Nutr Metab. 2016;2016:5168978.

Golden NH, Keane-Miller C, Sainani KL, Kapphahn CJ. Higher caloric intake in hospitalized adolescents with anorexia nervosa is associated with reduced length of stay and no increased rate of refeeding syndrome. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53:573–8.

Whitelaw M, Gilbertson H, Lam P-Y, Sawyer SM. Does aggressive refeeding in hospitalized adolescents with anorexia nervosa result in increased hypophosphatemia? J Adolesc Health. 2010;46:577–82.

Garber AK, Michihata N, Hetnal K, Shafer M-A, Moscicki A-B. A prospective examination of weight gain in hospitalized adolescents with anorexia nervosa on a recommended refeeding protocol. J Adolesc Health. 2012;50:24–9.

Matthews-Rensch K, Capra S, Palmer M. A systematic review of energy initiation rates and Refeeding Syndrome outcomes. Nutr Clin Pract. 2020; in press.

von Elm E, Altman D, Egger M, Pocock S, Gøtzsche P, Vandenbrouke J. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1453–7.

Skipper A. Refeeding syndrome or refeeding hypophosphatemia. Nutr Clin Pract. 2012;27:34–40.

Detsky AS, Baker J, Johnston N, Whittaker S, Mendelson R, Jeejeebhoy K. What is subjective global assessment of nutritional status? J Parenter Enter Nutr. 1987;11:8–13.

Bauer J, Capra S, Ferguson M. Use of the scored Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment (PG-SGA) as a nutrition assessment tool in patients with cancer. EJCN. 2002;56:779.

McNamee JP, Green JP, Allingham SF, Bird S, Blanchard MB, Lago LP, et al. Australian refined diagnosis related groups: version 7.0: definitions manual volume two; Australian Health Services Research Institute, Wollongong, Australia, 2013.

Queensland Government. Estimating energy, protein and fluid requirements for adult clinical conditions. Queensland: Queensland Government; 2017. https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0022/144175/est_rqts/pdf.

Queensland Health. Prescribing HYPO-Electrolyte Disturbances in Adults Queensland. Australia: Queensland Government; 201ḍ6. https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0023/700088/electrolyte-glines-adult.pdf.

Harris P, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde J. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–81.

Harris P, Taylor R, Minor B, Elliot V, Fernandez M, O’Neal L, et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208.

IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Macintosh, Version 25.0. IBM Corp., Armonk, New York, 2017.

Friedli N, Baumann J, Hummel R, Kloter M, Odermatt J, Fehr R, et al. Refeeding syndrome is associated with increased mortality in malnourished medical inpatients: secondary analysis of a randomized trial. Medicine. 2020;99:e18506.

Keys A, Brožek J, Henschel A, Mickelsen O, Taylor HL. The biology of human starvation (2 vols). Oxford: Univ. of Minnesota Press; 1950. xxxii, 1385-xxxii.

Dietitians Association of Australia. Evidence based practice guidelines for the nutritional management of malnutrition in adult patients across the continuum of care. Nutr Diet. 2009; 66(s3):S1–34.

O’connor G, Nicholls D. Refeeding hypophosphatemia in adolescents with anorexia nervosa: a systematic review. Nutr Clin Pract. 2013;28:358–64.

Kimpton S. A clinical audit to determine adherence in the Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital to the NICE guidelines for nutritional support in adults in the prevention and treatment of refeeding syndrome. Proc Nutr Soc. 2011;70 (OCE5).

Fleuret C, Reidlinger D, Whelan K, Rio A. Refeeding syndrome in hospital patients referred for enteral and parenteral nutrition. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2008;21:387–8.

Hamer C, Langley M. Audit of compliance with guidelines for the management of refeeding syndrome in Pennine Acute Hospitals NHS Trust. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2015;10:e198.

Corrigan G, O’Neill C, Connolly N, Deeney O, Fanning E, Guiden H, et al. An audit of the dietetic management of refeeding syndrome in a dublin teaching hospital. Clin Nutr. 2013;32:S184.

Bartkowiack L, Jones J, Bannerman E. Evaluation of the relative validity of food record charts (FRCs) used within the hospital setting to estimate energy and protein intakes. J Aging Res Clin Pract. 2015;4:e184–5.

Mahan LK, Escott-Stump S, Raymond JL, Krause MV. Krause’s food & the nutrition care process. 14th ed. Elsevier Health Sciences, Seattle, WA, 2012.

National Health and Medical Research Council. Nutrient reference values for Australia and New Zealand—introduction: what are nutrient reference values?. Australian Government, Australia, 2017. https://www.nrv.gov.au/introduction.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital Allied Health Research and Nutrition and Dietetics Department for their support in data collection and providing all required resources throughout the research process. This research was also supported by Dr. Peter Collins from the University of Queensland Human Movement and Nutrition Sciences School.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KMR and AY contributed to the conception of the project. KMR and CD contributed to the design of the research project. CD contributed to the acquisition of data. KMR, CD, and AY analysed and interpreted data. CD drafted the paper. KMR, AY, and CD revised the final paper. KMR and AY provided guidance throughout the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Drysdale, C., Matthews-Rensch, K. & Young, A. Further evidence to throw caution to the wind: outcomes using an assertive approach to manage refeeding syndrome risk. Eur J Clin Nutr 75, 91–98 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-020-0676-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-020-0676-6