Abstract

Background

As formula diets have demonstrated to be effective in reducing weight, we hypothesised that in patients with overweight or obesity and accompanied cardiovascular risk factors, combining a liquid formula diet with a lifestyle intervention is superior in reducing weight and improving cardiovascular risk factors than lifestyle intervention alone.

Methods

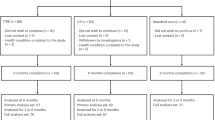

In this multicenter RCT 463 participants with overweight or obesity (BMI: 27–35 kg/m²; at least one additional co-morbidity of the metabolic syndrome) were randomised (1:2) into either a control group with lifestyle intervention only (CON, n = 155) or a lifestyle intervention group including a liquid meal replacement (INT, n = 308). Both groups used telemonitoring devices (scales and pedometers), received information on healthy diet and were instructed to increase physical activity. Telemonitoring devices automatically transferred data into a personalised online portal and acquired data were discussed. INT obtained a liquid meal replacement substituting three meals/day (~1200 kcal) within the first week. During weeks 2–4, participants replaced two meals/day and during weeks 5–26 only one meal/day was substituted (1300–1500 kcal/day). Follow-up was conducted after 52 weeks. Intention-to-treat analyses were performed. Primary outcome was weight change. Secondary outcomes comprised changes in cardiometabolic risk factors including body composition and laboratory parameters.

Results

From the starting cohort 360 (78%, INT: n = 244; CON: n = 116) and 317 (68%, INT: n = 216; CON: n = 101) participants completed the 26-weeks intervention phase and the 52-weeks follow-up. The estimated treatment difference (ETD) between both groups was −3.2 kg [−4.0; −2.5] (P < 0.001) after 12 weeks and −1.8 kg [−2.8; −0.8] (P < 0.001) after 52 weeks.

Conclusions

A low-intensity lifestyle intervention combined with a liquid meal replacement is superior regarding weight reduction and improvement of cardiovascular risk factors than lifestyle intervention alone.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Afshin A, Forouzanfar MH, Reitsma MB, Sur P, Estep K, Lee A, et al. Health effects of overweight and obesity in 195 countries over 25 years. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:13–27.

Konig D, Hörmann J, Predel HG, Berg A. A 12-month lifestyle intervention program improves body composition and reduces the prevalence of prediabetes in obese patients. Obes Facts. 2018;11:393–9.

Astbury NM, Piernas C. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of meal replacements for weight loss. Obes Rev. 2019;20:569–87.

Lean ME, Leslie WS, Barnes AC, Brosnahan N, Thom G, McCombie L, et al. Primary care-led weight management for remission of type 2 diabetes (DiRECT): an open-label, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet. 2017;391:541–51.

Steven S, Hollingsworth KG, Al-Mrabeh A, Avery L, Aribisala B, Caslake M, et al. Very low-calorie diet and 6 months of weight stability in type 2 diabetes: pathophysiological changes in responders and nonresponders. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:808–15.

Kempf K, Schloot NC, Gartner B, Keil R, Schadewaldt P, Martin S. Meal replacement reduces insulin requirement, HbA1c and weight long-term in type 2 diabetes patients with >100 U insulin per day. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2014;27(Suppl 2):S21–S27.

Konig D, Kookhan S, Schaffner D, Deibert P, Berg A. A meal replacement regimen improves blood glucose levels in prediabetic healthy individuals with impaired fasting glucose. Nutrition. 2014;30:1306–9.

Kempf K, Altpeter B, Berger J, Reuss O, Fuchs M, Schneider M, et al. Efficacy of the telemedical lifestyle intervention program TeLiPro in advanced stages of type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:863–71.

Kempf K, Rohling M. Individualized meal replacement therapy improves clinically relevant long-term glycemic control in poorly controlled type 2 diabetes patients. Nutrients. 2018;10:1022.

American Diabetes Association. 4. Lifestyle management: standards of medical care in diabetes-2018. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:S38–S50.

Davies MJ, D’Alessio DA, Fradkin J, Kernan WN, Mathieu C, Mingrone G, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2018. A consensus report by the American diabetes association (ADA) and the European association for the study of diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2018;41:2669–701.

Davies MJ, D’Alessio DA, Fradkin J, Kernan WN, Mathieu C, Mingrone G, et al. Management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes, 2018. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetologia. 2018;61:2461–98.

Lean MEJ, Leslie WS, Barnes AC, Brosnahan N, Thom G, McCombie L, et al. Durability of a primary care-led weight-management intervention for remission of type 2 diabetes: 2-year results of the DiRECT open-label, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7:344–55.

Yumuk V, Tsigos C, Fried M, Schindler K, Busetto L, Micic D, et al. European guidelines for obesity management in adults. Obes Facts. 2015;8:402–24.

Röhling M, Kempf K, Banzer W, Berg A, Braumann KM, Tan S. et al. Prediabetes conversion to normoglycemia is superior adding a low-carbohydrate and energy deficit formula diet to lifestyle intervention-a 12-month subanalysis of the ACOORH trial. Nutrients. 2020;12:2022.

Koohkan S, McCarthy D, Berg A. The effect of a soy-yoghurt-honey product on excess weight and related Page health risk factors—a review. J Nutr Health Food Sci. 2017;5:1–10.

Bosy-Westphal A, Schautz B, Later W, Kehayias JJ, Gallagher D, Müller MJ. What makes a BIA equation unique? Validity of eight-electrode multifrequency BIA to estimate body composition in a healthy adult population. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2013;67(Suppl 1):S14–S21.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Investigational New Drug Application (IND). Sec. 312.32 IND Safety Reporting. 2018: U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Berg A, Deibert P, Landmann U, König D, Schmidt-Trucksäss A, Rücker G, et al. Gewichtsreduktion ist machbar. Halbjahresergebnisse einer klinisch kontrollierten, randomisierten Interventionsstudie mit übergewichtigen Erwachsenen. Ernährungs-Umsch 2003;50:386–93.

Astbury NM, Piernas C. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of meal replacements for weight loss. Obes Rev. 2019;20:569–87.

Lowe MR, Butryn ML, Zhang F. Evaluation of meal replacements and a home food environment intervention for long-term weight loss: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018;107:12–19.

Rock CL, Flatt SW, Sherwood NE, Karanja N, Pakiz B, Thomson CA. Effect of a free prepared meal and incentivized weight loss program on weight loss and weight loss maintenance in obese and overweight women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304:1803–10.

Ahern AL, Wheeler GM, Aveyard P, Boyland EJ, Halford JCG, Mander AP, et al. Extended and standard duration weight-loss programme referrals for adults in primary care (WRAP): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2214–25.

Leslie WS, Taylor R, Harris L, Lean ME. Weight losses with low-energy formula diets in obese patients with and without type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Obes. 2017;41:96–101.

Stefan N, Haring HU, Schulze MB. Metabolically healthy obesity: the low-hanging fruit in obesity treatment? Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;6:249–58.

Sellahewa L, Khan C, Lakkunarajah S, Idris I. A systematic review of evidence on the use of very low calorie diets in people with diabetes. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2017;13:35–46.

Jackness C, Karmally W, Febres G, Conwell IM, Ahmed L, Bessler M, et al. Very low-calorie diet mimics the early beneficial effect of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on insulin sensitivity and beta-cell function in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes. 2013;62:3027–32.

Baillot A, Romain AJ, Boisvert-Vigneault K, Audet M, Baillargeon JP, Dionne IJ, et al. Effects of lifestyle interventions that include a physical activity component in class II and III obese individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0119017.

Bhanpuri NH, Hallberg SJ, Williams PT, McKenzie AL, Ballard KD, Campbell WW, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk factor responses to a type 2 diabetes care model including nutritional ketosis induced by sustained carbohydrate restriction at 1 year: an open label, non-randomized, controlled study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17:56.

Acknowledgements

The ACOORH group thanks their consortium members for their excellent work (a complete list of all consortium members including those who did not met authorship criteria can be seen in the Supplementary information). Furthermore, the authors thank their study staff for their excellent work and Dr. Thomas Keller (ACOMED statistik®, Leipzig, Germany) for his support in the statistical analysis. We would also like to thank Verena Heinicke, Katrin Esefeld, Nina Schaller and Johannes Scherr for their significant support of performing the trial at the local Munich site. The study centre of Freiburg thanks their colleagues Sadaf Koohan and Andrea Stensitzky for their great support by conducting the study. We, the West-German Centre of Diabetes and Health, Düsseldorf, thank our study nurse Bettina Prete for her excellent work.

ACOORH study group

Martin Halle1,2, Nina Schaller1, Martin Röhling3, Kerstin Kempf3, Stephan Martin3,12, Winfried Banzer4, Klaus Michael Braumann5, Jürgen Scholze8, Dagmar Führer-Sakel9, Susanne Tan9, Hans Georg Predel7, Aloys Berg11, Sadaf Koohkan13, David McCarthy6, Hermann Toplak10, Michel Pinget14

Funding

The study was financially supported by the Almased-Wellness-GmbH. The funder had no influence on study hypothesis/design, data collection, execution, data analysis, interpretation, manuscript preparation and/or publication decisions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

AB had the initial idea for the study design and initiated the study. The protocol was designed together with HT and with additional contributions of SM. MH and MR drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript and approved the final version. WB, AB, KMB, DMC, MH, KK, SM, HGP, JS, DF-S and HT collected data at their local sites. A Berg is the guarantor of this work and all co-authors had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

WB, AB, KMB, MH, KK, DMC, HGP, JS, DF-S and HT received research support for their departments from the Almased-Wellness-GmbH to perform the study. AB, MH, DMC and HT have also received speakers' honoraria (category: personal financial interests) from Almased-Wellness-GmbH. All four authors declare that their honoraria had no influence on their contribution to the study design, data collection, data analysis, manuscript preparation and/or publication decisions. NS and MR declare no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Consortium representative: Prof. Dr. Aloys Berg (principal investigator). Faculty of Medicine, University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany, Breisacher Str. 153, 79110 Freiburg, phone: +49 (0)172-74 14 771, E-mail: aloys.berg@klinikum.uni-freiburg.de.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Halle, M., Röhling, M., Banzer, W. et al. Meal replacement by formula diet reduces weight more than a lifestyle intervention alone in patients with overweight or obesity and accompanied cardiovascular risk factors—the ACOORH trial. Eur J Clin Nutr 75, 661–669 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-020-00783-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-020-00783-4

This article is cited by

-

Empfehlungen zur Ernährung von Personen mit Typ-2-Diabetes mellitus

Die Diabetologie (2024)

-

Adipositas und Typ-2-Diabetes (Update 2023)

Wiener klinische Wochenschrift (2023)

-

The suitability, acceptability, and feasibility of a culturally contextualized low-calorie diet among women at high risk for diabetes mellitus in Kerala: a mixed-methods study

International Journal of Diabetes in Developing Countries (2023)

-

Empfehlungen zur Ernährung von Personen mit Typ-2-Diabetes mellitus

Die Diabetologie (2023)

-

Empfehlungen zur Ernährung von Personen mit Diabetes mellitus Typ 2

Die Diabetologie (2022)