Abstract

Background/Objectives

Investigating the effect on post-prandial glycemic and venous serum insulin response of an apple drink following the conversion of its glucose to gluconate.

Subjects/Methods

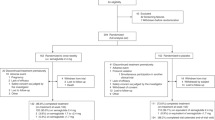

In a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial with cross-over design, 30 male adults with impaired fasting glucose (IFG) received a drink of 500 ml: 1. Verum: Apple juice treated with invertase, glucose oxidase/catalase (glucose 0.05 g; gluconate 18.2 g); 2. Control: Untreated apple juice (free glucose 8.5 g; bound glucose 6.7 g; gluconate below detection limit). Postprandial fingerprick capillary blood glucose and venous serum insulin were measured twice at baseline and at times 0 (start of drink), 15, 30, 45, 60, 90 and 120 min. Gastrointestinal symptoms, stool consistency and satiety were also assessed.

Results

The incremental area under the curve (iAUC120) of glucose levels (primary parameter) was significantly lower after verum (mean ± SD: 63.6 ± 46.7 min × mmol/l) compared to control (mean ± SD: 198 ± 80.9 min × mmol/l) (ANOVA F = 137.4, p < 0.001; α = 0.05). Also, iAUC120 of venous serum insulin levels (secondary parameter) was significantly lower after verum (mean ± SD: 2045 ± 991 min × mmol/l) compared to control (3864.3 ± 1941 min × mmol/l), (ANOVA F = 52.94, p < 0.001; α = 0.025). Further parameters of glucose metabolism and ISI = 2/[AUC venous serum insulin × AUC glucose +1] were also improved after verum compared to control. Verum increased stool frequency and decreased stool consistency, as assessed by Bristol stool form scale.

Conclusions

By enzymatic treatment of apple juice its sugar content could be reduced by 21% and postprandial glycemic and venous serum insulin response by 68 and 47%, respectively resulting in a reduction of glycemic load by 74.6% without any adverse gastrointestinal side-effects.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Schrezenmeir J, Knutsen SH, Ballance S. Improved sugar-depleted fruit or vegetable juice and juice-retaining fruit or vegetable derived matter, methods of producing the same and the use thereof to maintain health and to treat and prevent medical ailments Patent application. 2016:WO2016051190A1.

Asano T, Yuasa K, Kunugita K, Teraji T, Mitsuoka T. Effects of gluconic acid on human faecal bacteria. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 1994;7:247–56.

OECD SIDS. Initial assessment report on gluconic acid and its derivatives for SIAM 18. Paris, France; 2004 20–23 April 2004.

EFSA. Guidance on the scientific requirements for health claims related to appetite ratings, weight management, and blood glucose concentrations. EFSA J. 2012;10:2604.

FAO/WHO. Carbohydrates in human nutrition. Report of a Joint FAO/WHO Expert Consultation. FAO Food Nutr Pap. 1998;66:1–140.

Joint FAO/WHO Expert committee on food additives (JECFA). Glucono-delta-lactone and the calcium, magnesium, potassium and sodium salts of gluconic acid. Geneva: WHO; 1999.

European Commission. Commission Directive 2008/100/EC of 28 October 2008 amending Council Directive 90/496/EEC on nutrition labelling for foodstuffs as regards recommended daily allowances, energy conversion factors and definitions. Official Journal of the European Union. 2008;L 285:9–12.

The expert comittee on the diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Follow-up report on the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:3160–7.

Higgins J, Green S (eds). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011.

Svedlund J, Sjodin I, Dotevall G. GSRS - a clinical rating-scale for gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and peptic-ulcer disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1988;33:129–34.

Dimenäs E, Glise H, Hallerbäck B, Hernqvist H, Svedlund J, Wiklund I. Well-being and gastrointestinal symptoms among patients referred to endoscopy owing to suspected duodenal ulcer. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995;30:1046–52.

Revicki DA, Wood M, Wiklund I, Crawley J. Reliability and validity of the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Qual Life Res. 1997;7:75–83.

Lewis S, Heaton K. Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:920–4.

Flint A, Raben A, Astrup A, Holst JJ. Glucagon-like peptide 1 promotes satiety and suppresses energy intake in humans. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:515–20.

Flint A, Raben A, Blundell J, Astrup A. Reproducibility, power and validity of visual analogue scales in assessment of appetite sensations in single test meal studies. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:38–48.

Wolever T, Vorster H, Björck I, Brand-Miller J, Brighenti F, Mann J, et al. Determination of the glycaemic index of foods: interlaboratory study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003;57:475–82.

Foster-Powell K, Holt SH, Brand-Miller JC. International table of glycemic index and glycemic load values: 2002. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76:5–56.

Wolever TMS, Brand-Miller JC, Abernethy J, Astrup A, Atkinson F, Axelsen M, et al. Measuring the glycemic index of foods: interlaboratory study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:247S–57S.

Wolever TM The glycaemic index: a physiological classification of dietary carbohydrate: Cabi; 2006.

Brand-Miller JC, Stockmann K, Atkinson F, Petocz P, Denyer G. Glycemic index, postprandial glycemia, and the shape of the curve in healthy subjects: analysis of a database of more than 1000 foods. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;89:97–105.

Liu S, Willett WC, Stampfer MJ, Hu FB, Franz M, Sampson L. et al. A prospective study of dietary glycemic load, carbohydrate intake, and risk of coronary heart disease in US women–. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71:1455–61.

Belfiore F, Iannello S, Volpicelli G. Insulin sensitivity indices calculated from basal and OGTT-induced insulin, glucose, and FFA levels. Mol Genet Metab. 1998;63:134–41.

Belfiore F. Insulin sensitivity indexes calculated from oral glucose tolerance test data. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:1595–6.

Johnston KL, Clifford MN, Morgan LM. Coffee acutely modifies gastrointestinal hormone secretion and glucose tolerance in humans: glycemic effects of chlorogenic acid and caffeine. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:728–33.

Oh K, Hu FB, Cho E, Rexrode KM, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE, et al. Carbohydrate intake, glycemic index, glycemic load, and dietary fiber in relation to risk of stroke in women. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161:161–9.

Augustin LSA, Kendall CWC, Jenkins DJA, Willett WC, Astrup A, Barclay AW. et al. Glycemic index, glycemic load and glycemic response: An International Scientific Consensus Summit from the International Carbohydrate Quality Consortium (ICQC). Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;25:795–815.

Kahn S. The relative contributions of insulin resistance and beta-cell dysfunction to the pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2003;46:3–19.

Ballance S, Knutsen SH, Fosvold ØW, Fernandez AS, Monro J. Predicting mixed-meal measured glycaemic index in healthy subjects. Eur J Nutr. 2018:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-018-1813

Krause M, Mahan L. Food, nutrition and diet therapy: A textbook of nutritional care. Philadelphia: WB Sanders; 1984.

Biagi G, Piva A, Moschini M, Vezzali E, Roth F. Effect of gluconic acid on piglet growth performance, intestinal microflora, and intestinal wall morphology. J Anim Sci. 2006;84:370–8.

Chenoweth MB, Civin H, Salzman C, Cohn M, Gold H. Further studies on the behavior of gluconic acid and ammonium gluconate in animals and man. J Lab Clin Med. 1941;26:1574–82.

Acknowledgements

We thank Andrea Liesegang, Maria Gatzmange, Tara Dezhahang and Hanne Zobel for their excellent support and for technical assistance. This research was financed by the “HealthBoost” project in the FORNY2020 verification program of the Research Council of Norway (Grant no: 243871). Additional financial support to SB and SHK was provided by a grant from the Norwegian Fund for Research Fees for Agricultural Products (Norwegian Research Council Grant no. 262300).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CL, SB, SHK, EP, ES, AP and JS contributed to the design of the study, SB and SHK to the production of the test products, CL, ES and AP to the study conduct, CL, SB, SHK, EP, ES and JS to data evaluation, all authors to the interpretation of the results; JS wrote the first draft of the manuscript, to which all other authors contributed.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The study was conducted in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (32), the guidelines for Good Clinical Practice (ICH E6) (33), and in accordance with European and National regulatory requirements. All clinical data were collected at the study site of the Clinical Research Center Kiel GmbH. Supplementary information is available at EJCN’s website.

Conflict of interest

SB, SHK, JS: Are inventors of a patent on this matter [1] and hold shares (as does CL) in Glucozero GmBH. This company is currently licensing the patent from Nofima AS (full-time employer of SB and SHK). The remaining authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Laue, C., Ballance, S., Knutsen, S.H. et al. Glycemic response to low sugar apple juice treated with invertase, glucose oxidase and catalase. Eur J Clin Nutr 73, 1382–1391 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-019-0421-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-019-0421-1