Abstract

Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide)-based hydrogel particles (GPs) with different sized hydrogel networks were developed and used to confine a palladium (Pd) catalyst. The size of the gel network was tuned by varying the feed ratio of the cross-linking monomer. Nanosized-Pd(0) was loaded into the GPs, which contain a tertiary-amine ligand, via Pd-ion adsorption and subsequent reduction. The Pd-loaded GPs were used as the catalyst for a Suzuki coupling reaction between phenylboronic acid and 4-bromobenzoic acid in water at 30 °C. Due to the hydrophilic reaction platform provided by the hydrogel matrix of the GPs, the catalytic efficiencies of Pd-loaded GPs were significantly higher than those of commercially available Pd-loaded supports. Notably, the Pd-loaded GPs with the smallest gel networks were highly durable for Suzuki coupling reactions. It is plausible that the smaller network minimized or prevented the enlargement of Pd(0) during the catalytic cycle. The facile synthesis of the GPs, environmentally benign catalytic system, and high catalytic durability and activity of these Pd-loaded GPs are all important factors for the industrial application of these materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In organic synthesis, carbon–carbon bond formation using palladium (Pd)-catalyzed coupling reactions is well established. In particular, the Suzuki coupling reaction between boronic acids and aryl halide derivatives is an important tool for the synthesis of aromatic compounds, which often constitute pharmaceuticals, agrochemicals, and natural products [1, 2]. The immobilization of Pd catalysts is an attractive methodology that allows for the simple recovery and reuse of a catalyst without the need for scavengers, in contrast to homogeneous catalysts [3, 4]. The recent and increasing interest in green and sustainable chemistry has driven the development of organic synthesis under mild conditions with low catalyst ratios, water as a solvent, and ambient temperatures [5, 6]. Thus, understanding and developing immobilized Pd catalysts that are highly stable and active in exclusively aqueous media are very important.

Pd catalysts immobilized onto the surfaces of supports are typically on the nano-scale, which contributes to their excellent catalytic activities [3]. However, surface-immobilized Pd catalysts gradually form bulky Pd over many catalytic cycles, which leads to their deactivation [7]. To overcome this problem, Pd catalysts confined within a support material have been designed [8]. Catalysts in which the Pd is confined are highly resistant to leaching and enlargement during repeated catalytic cycles, which results in higher turnover numbers (TONs).

Pd catalysts have been confined within a variety of support materials, including mesoporous silica [9,10,11,12,13,14], sulfur-modified metals [8, 15, 16], metal organic frameworks[17,18,19,20,21], dendrimers[22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31], covalent organic frameworks [32,33,34,35,36], and microporous organic polymers [37,38,39,40], for use in carbon–carbon bond formation. Although these confined catalyst systems have overcome some problems, the ability for the substrate to access the catalyst is often inhibited. Thus, an investigation on the effects of confinement on catalytic performance should allow the rational design of immobilized Pd catalysts.

We have previously reported the development of nanosized Pd catalysts confined within poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAm)-based hydrogel particles (GPs) via coordination to tertiary-amino groups in the gel network to yield Pd-loaded GPs (Pd/GPs) [41, 42]. The Pd/GPs successfully catalyzed both hydrogenation and Suzuki coupling reactions in an aqueous solution because the GPs were well dispersed in the aqueous media.

Herein, a new library of PNIPAm-based GPs with different-sized gel networks was prepared to investigate and understand the catalytic performance of Pd confined within GPs. Gel networks with a defined size were successfully fabricated, and the nanosized Pd was firmly confined within the GPs. Suzuki coupling reactions using the fabricated Pd/GPs were very fast under completely aqueous conditions at ambient temperature (30 °C) compared to commercially available Pd-loaded supports. Importantly, confining the Pd catalysts within the gel networks of defined sizes efficiently prevented deactivation of the Pd catalyst. This work led to the largest reported TON for a Suzuki coupling reaction under completely aqueous conditions at ambient temperature using an immobilized Pd catalyst.

Experimental

Materials

Water with a conductivity of 18.2 MΩ cm (Milli-Q, Millipore Co., Bedford, MA, USA) was used in all experiments. NIPAm (Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd., Osaka, Japan), N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)methacrylamide (DMAPM, Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), N,N’-methylenebisacrylamide (BIS, Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd.), cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB, Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd.) and 2,2’-azobis(2-amidinopropane) dihydrochloride (AAPD, Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd) were used as the gel matrix, tertiary-amine ligand, cross-linker, surfactant, and radical initiator, respectively. NIPAm was purified by recrystallization from benzene/n-hexane and dried in vacuo at room temperature. The polymerization inhibitor in DMAPM was removed using an activated alumina column. K2PdCl4 (Sigma-Aldrich Co.) and NaBH4 (Tokyo Chemical Industry Co. Ltd.) were used to prepare the Pd-loaded catalyst. Pd-loaded carbon (Pd/C, Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd) and Pd-loaded alumina (Pd/Al2O3, Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd) were also used as reference Pd catalysts. Phenylboronic acid (Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd.), 4-bromobenzoic acid (Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd.), and Na2CO3 (Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd.) were used to prepare the stock solution of substrates. 4-Phenylbenzoic acid (Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd) was used to prepare the standard solution for calibration of the products in the Suzuki coupling reaction.

Preparation and characterization of GPs with different-sized gel networks

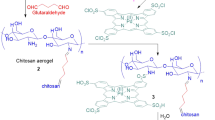

PNIPAm-based hydrogel particles (GPs) were used as a support for the Pd catalysts and were synthesized by the copolymerization of NIPAm with a tertiary-amine ligand and a cross-linker above the lower critical solution temperature of PNIPAm (Scheme 1) [41, 42]. NIPAm (100−10−x mol%), DMAPM (10 mol%), BIS (x = 5, 10, and 30 mol%), and CTAB were dissolved in water to adjust the total monomer concentrations (Supplementary Information, Table S1). The monomer solutions were degassed with N2 gas for more than 1 h, followed by the addition of AAPD as a radical initiator (0.83 mol% of total monomers) to each solution. The mixture was stirred at 70 °C for 3 h. The resulting milky solution was dialyzed (molecular-weight cutoff: 12,000–14,000) against water for 3 days, in which the water was changed 9 times. After freeze-drying a portion of the dialyzed solution, the yield of GPs was determined from the weight of the dry GPs. The hydrodynamic diameter and amount of amine in the GPs were estimated using dynamic light scattering (DLS) and acid–base titration, respectively (see the Supplementary Information). The time course of the monomer (NIPAm, DMAPM, and BIS) conversion was also measured during the copolymerization of GPs in D2O under similar polymerization conditions (see the Supplementary Information).

Loading of nanosized Pd(0) into GPs

Pd-loaded GPs (Pd/GPs) were prepared by the adsorption of Pd(II) ions, which were subsequently reduced to Pd(0) (Scheme 1) [41, 42]. After freeze-drying and ion exchange, each of the GPs (100 mg) was mixed with K2PdCl4 (0.075 mmol) in an aqueous HCl solution (1.0 mmol L−1, 75 mL). The solutions were shaken at room temperature for 2 days. The solution was dialyzed (molecular-weight cutoff: 10,000) against an aqueous HCl solution (1.0 mmol L−1) for 3 days, in which the HCl solution was changed 5 times. After washing, the GPs, the Pd ions in the GPs were reduced to Pd(0) using an aqueous NaBH4 solution, until the pH reached 8. The solution was then dialyzed (molecular-weight cutoff: 10,000) against water for 3 days, in which the water was changed 5 times. After freeze-drying, the resulting solution, Pd/GPs were obtained as a brown powder. The amount of Pd loaded into the GPs was estimated by immersion in aqua regia and analysis using inductively coupled plasma-atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES, ICPS-8100, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) (see the Supplementary Information). The Pd(0) in the GPs was observed using transmission electron microscopy (TEM, TECNAI 20, Philips FEI, Netherlands). The sizes of the Pd(0) particles loaded into the GPs were measured for 200 particles of Pd(0) using the TEM images (see the Supplementary Information).

Suzuki coupling reaction using Pd-loaded supports

Suzuki coupling reactions between phenylboronic acid and 4-bromobenzoic acid in aqueous media were conducted. Phenylboronic acid (200 mmol L−1, 1.0 eq.), 4-bromobenzoic acid (220 mmol L−1, 1.1 eq.), and Na2CO3 (220 mmol L−1, 1.1 eq.) were dissolved in water (15 mL) and stirred at 30 °C for 1 h. The catalyzed reaction was initiated by the addition of Pd/GPs, Pd/C, or Pd/Al2O3 (5 × 10−2 mol% Pd) to the substrate solution. A small aliquot was taken from the reaction mixture periodically, and the reaction progress was monitored using a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC, LC-2000Plus, JASCO Co., Tokyo, Japan) system with a reverse-phase column (Mightysil RP-18 GP 250-4.6, Kanto Chemical Co., Tokyo, Japan) and an ultraviolet detector. A solution of acetonitrile and water (50/50 v/v) including 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid was employed as the mobile phase. The percent conversion of phenylboronic acid was estimated using Eq. 1:

where the subscript 0 denotes the initial conditions. The apparent reaction rate constants (k) in the Suzuki coupling reaction were estimated by following the second-order reaction model:

where t is the reaction time. The concentration of 4-bromobenzoic acid was estimated using Eq. 3:

where a is the feed ratio of 4-bromobenzoic acid to phenylboronic acid. Therefore, Eq. 2 was converted into Eq. 4:

The turnover numbers (TONs) and initial turnover frequencies (TOFs) of the Pd catalyst were calculated using Eqs. 5 and 6, respectively:

Evaluation of catalytic durability of Pd/GPs in the Suzuki coupling reaction

Phenylboronic acid (200 mmol L−1, 1.0 eq.), 4-bromobenzoic acid (220 mmol L−1, 1.1 eq.), and Na2CO3 (220 mmol L−1, 1.1 eq.) were dissolved in water (15 or 150 mL) and stirred at 30 °C for 1 h. The catalyzed reaction was initiated by the addition of Pd/GPs (5 × 10−3 or 5 × 10−4 mol% Pd) to the substrate solution. A small aliquot was taken from the reaction mixture periodically, and the reaction progress was monitored using an HPLC system. After the reaction, the reaction mixture was dialyzed (molecular-weight cutoff: 20,000) against water for ~1 day, during which the aqueous solution was changed 3 times to recover the spent Pd/GPs. The sizes of the Pd(0) particles loaded into the GPs were measured for 200 Pd(0) particles using TEM images (see the Supplementary Information).

Results and Discussion

Preparation and characterization of GPs with different-sized gel networks

The GPs were synthesized by the pseudo-precipitation copolymerization of NIPAm (100−10−x mol%), DMAPM (10 mol%), and BIS (x = 5, 10, and 30 mol%) [41, 42]. These materials acted as the gel matrix, tertiary-amine ligand, and cross-linker, respectively (Scheme 1). Tuning the feed ratio of BIS gave GP5 (x = 5 mol%), GP10 (x = 10 mol%), and GP30 (x = 30 mol%) with yields of 93, 78, and 78%, respectively (Supplementary Information, Table S1). DLS confirmed that the sizes of the resulting GPs were monomodal with hydrodynamic diameters of 99–175 nm at 30 °C (Supplementary Information, Supplementary Figure S1a). The hydrodynamic diameters changed with the temperature (Supplementary Figure S1b). From the acid–base titrations, the tertiary-amine densities in GP5, GP10, and GP30 were determined to be 0.747, 0.696, and 0.612 mmol g−1, respectively (Supplementary Figure S2 and Supplementary Table S2). Monitoring the copolymerization of the GPs in D2O using 1H NMR gave the time course of monomer conversion (Supplementary Figure S3).

All the obtained GPs were well dispersed in water media (Figure S1a). Additionally, the hydrodynamic diameters of the GPs were dependent on the temperature, which was attributed to the phase transition of PNIPAm (Figure S1b). The volume-change responsiveness to temperature was suppressed with an increased BIS content. The increase in the cross-linker content in the PNIPAm gel was considered to be proportional to the decrease in the size of the gel network [43]. The network sizes of the PNIPAm gels with BIS contents of 5, 10, and 30 mol% were calculated to be 7.9, 5.2, and 2.8 nm, respectively [44]. The sizes of the GP gel networks were observed to be controlled by their BIS contents. From the results of the acid–base titrations, tertiary-amine ligands were incorporated into the GPs (incorporation ratio, Supplementary Figure S2 and Supplementary Table S2). The monomer consumption was monitored using 1H NMR, which allowed us to determine the localization of the amine ligands or cross-linkers in the GPs (Supplementary Figure S3). As the incorporation ratios of the NIPAm, DMAPM, and BIS monomers were almost identical to their respective feed ratios during the polymerization, the amine ligands and cross-linker were incorporated relatively uniformly in the resulting GPs.

Loading of nanosized Pd(0) into the GPs and TEM observations

Pd(0) was loaded into GP5, GP10, and GP30 via coordination to the tertiary-amine groups [41, 42]. The resulting GPs turned black after the Pd(0) loading. The amount of Pd loaded into GP5, GP10, and GP30 was determined by immersing the material in aqua regia and analyzing it using ICP-AES, which gave values of 0.100, 0.089, and 0.105 mmol g−1, respectively. Using TEM, Pd(0) was observed to be uniformly distributed throughout GP5, GP10, and GP30, with average particle sizes of 2.5 ± 0.3, 2.2 ± 0.4, and 2.5 ± 0.5 nm, respectively (Fig. 1). Because the average size of the Pd(0) loaded into the GPs was smaller than the size of the gel networks (7.9, 5.2, and 2.8 nm for PNIPAm gels with BIS contents of 5, 10, and 30 mol%, respectively) [44], the presence of Pd within the gel networks was assumed.

Suzuki coupling reaction using Pd-loaded supports in aqueous media

To evaluate the catalytic performance of the Pd/GPs, Suzuki coupling reactions between phenylboronic acid and 4-bromobenzoic acid under completely aqueous conditions (Table 1) were conducted. The catalytic reactions were performed using Pd/GPs, Pd/C, or Pd/Al2O3 (5 × 10−2 mol% Pd). After using the catalysts, no Pd leaching in the reaction mixture was detected by ICP-AES ( < 10 p.p.b.). Surprisingly, the Pd/GPs converted all the phenylboronic acid into 4-phenylbenzoic acid (conversion percentages of >96%), while the coupling reactions using catalytic Pd/C and Pd/Al2O3 had conversions of only 62 and 58%, respectively. Notably, the turnover frequencies (TOFs) of the Pd/GPs were significantly higher (1.28–5.06 × 103 h−1) than those obtained using Pd/C and Pd/Al2O3 (1.30 × 102 and 1.10 × 102 h−1, respectively). The catalytic efficiencies normalized by the surface area of Pd(0) were also estimated using TEM images of Pd/GPs, Pd/C, and Pd/Al2O3 (Table 1, Fig. 1a and Supplementary Figure S4).

Using Pd/GPs, the Pd catalytic cycles for the Suzuki coupling reactions were fast enough to give the desired product. It is expected that the diffusivities of both the substrates and the product within the PNIPAm gel network are comparable to those in bulk water [45]. Although the Pd catalysts were effectively confined within the GPs via coordination to the tertiary-amino groups in the gel network, the high flexibility of the PNIPAm chains in aqueous media allowed the substrates to access the catalyst. As a result, the Pd/GPs exhibited TOFs 10 times greater than those of commercially available Pd-loaded supports. Although immobilizing the Pd catalyst on supports often deteriorates the catalytic efficiency due to limited diffusion of the substrates and/or product, using GPs as a reaction platform overcame this disadvantage of immobilized catalysts.

Catalytic durability of Pd confined within the GPs

The catalytic durability of Pd/GP5, Pd/GP10, and Pd/GP30 was evaluated in Suzuki coupling reactions. When the amount of Pd added to the reactions was decreased to 5 × 10−3 mol%, Pd/GP10 and Pd/GP30 achieved conversions of > 99%, while Pd/GP5 no longer catalyzed the reaction and gave only 68% conversion (Fig. 2a). Surprisingly, when the amount of added Pd was decreased to 5 × 10−4 mol%, only Pd/GP30 could complete the coupling reaction, with a conversion of 97% (TON of 1.94 × 105), while Pd/GP5 and Pd/GP10 achieved conversions of only 8 and 83% (Fig. 2b). ICP-AES analysis did not detect any leaching of Pd ( < 10 ppb) from the GPs after all the catalytic reactions.

Pd/GP30, which was composed of a highly cross-linked polymer hydrogel network, exhibited amazing catalytic durability in the Suzuki coupling reaction in water at ambient temperature. The TON (1.94 × 105) for the Suzuki coupling reaction using Pd/GP30 is the largest among those reported when using immobilized Pd catalysts for catalytic reactions under completely aqueous conditions (1.15 × 105 for mesoporous silica [13] and 8.50 × 104 for a dendrimer [29]). Moreover, the catalytic activity of Pd/GP30 in air was stable for a year (Supplementary Information, Supplementary Figure S6). Thus, Pd/GP30 could be used without deoxygenating the reaction mixture, which can be attributed to the hydrophilic reaction platform in the GPs comprising a hydrogel matrix. Tan and coworkers reported that Pd confined within hyper-cross-linked microporous polymers made from aryl networks were highly durable compared with those confined within polymers with less cross-linking [38], which supports the results in our GP systems. The microenvironment around Pd in the GPs likely influenced the catalytic durability in the Suzuki coupling reaction.

Confinement effect of Pd within the GPs on catalytic durability

The size distribution of Pd(0) in the GPs was estimated from TEM images before and after their use in Suzuki coupling reactions (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Figure S5). After use in a Suzuki coupling reaction with 5 × 10−3 and 5 × 10−4 mol% Pd/GPs, aggregates of Pd(0) with sizes ranging from 5–13 nm were observed in the spent GP5 and GP10 (Fig. 3). Interestingly, all the Pd(0) loaded into GP30 had a size of < 5 nm, even after 1.94 × 105 catalytic cycles in the Suzuki coupling reaction.

The TEM observations revealed that the Pd(0) within the spent GP5 and GP10 was enlarged compared with the fresh catalysts, which was caused by aggregation and Ostwald ripening (Fig. 3) [46]. It is noteworthy that the enlargement of Pd(0) within the GP30 was successfully prevented to achieve the highest TON for the Suzuki coupling reaction. Thus, confinement of the Pd catalyst within the GPs imparted catalytic durability to this Suzuki coupling reaction. The TON for the Pd catalyst in GPs improved as the size of the gel network in the GPs decreased. Using GPs with different-sized gel networks, we determined that confining a Pd catalyst within a highly cross-linked polymer prevented aggregation of the Pd during the catalytic cycle. Moreover, because the hydrophilic reaction platform in the GPs was composed of a hydrogel matrix, Pd catalyst loaded in GP30 gave the highest TON (1.94 × 105) for the Suzuki coupling reaction in exclusively aqueous media at ambient temperature among those for immobilized Pd catalysts that have been reported under similar conditions.

Conclusions

Pd was confined within PNIPAm-based hydrogel particles for use as a catalyst in a Suzuki coupling reaction between phenylboronic acid and 4-bromobenzoic acid in completely aqueous media at ambient temperature. The GPs were synthesized by copolymerization of a gel matrix, a tertiary-amine ligand, and cross-linking monomers. The size of the gel networks was tuned by varying the feed ratio of the cross-linking monomer. Pd catalysts were loaded into the GPs by Pd-ion adsorption and subsequent reduction, which yielded Pd/GPs that contained Pd(0) with an average particle size of several nanometers. The flexible polymer chains allowed the substrates to easily access the Pd catalysts confined within the GPs. The catalytic performance of the Pd/GPs was significantly better than those of commercially available Pd-loaded supports. Notably, Pd/GP with the smallest gel network (Pd/GP30) was highly durable. It is plausible that the smaller network minimized or prevented the enlargement of Pd(0) during the catalytic cycles. The facile synthesis of the GPs, environmentally benign catalytic system (completely aqueous at ambient temperature (30°C)), and high catalytic durability and activity of Pd/GPs are all important factors for their industrial application. We expect that this confined catalyst system will have significant impacts on reactions catalyzed by immobilized metals using green and sustainable chemistry.

References

Miyaura N, Suzuki A. Palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions of organoboron compounds. Chem Rev. 1995;95:2457–83.

Johansson Seechurn CC, Kitching MO, Colacot TJ, Snieckus V. Palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling: a historical contextual perspective to the 2010 nobel prize. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:5062–85.

Roucoux A, Schultz J, Patin H. Reduced transition metal colloids: a novel family of reusable catalysts? Chem Rev. 2002;102:3757–78.

Phan NT, Van Der Sluys M, Jones CW. On the nature of the active species in palladium catalyzed Mizoroki-Heck and Suzuki-Miyaura couplings—Homogeneous or heterogeneous catalysis: a critical review. Adv Synth Catal. 2006;348:609–79.

Yin L, Liebscher J. Carbon-carbon coupling reactions catalyzed by heterogeneous palladium catalysts. Chem Rev. 2007;107:133–73.

Lamblin M, Nassar-Hardy L, Hierso JC, Fouquet E, Felpin FX. Recyclable heterogeneous palladium catalysts in pure water: Sustainable developments in Suzuki, Heck, Sonogashira and Tsuji–Trost reactions. Adv Synth Catal. 2010;352:33–79.

Felpin FX, Ayad T, Mitra S. Pd/C: an old catalyst for new applications-its use for the Suzuki-Miyaura reaction. Eur J Org Chem. 2006;2006:2679–90.

Arisawa M, Al-Amin M, Honma T, Tamenori Y, Arai S, Hoshiya N, Sato T, Yokoyama M, Ishii A, Takeguchi M, Miyazaki T, Takeuchi M, Maruko T, Shuto S. Formation of self-assembled multi-layer stable palladium nanoparticles for ligand-free coupling reactions. RSC Adv. 2015;5:676–83.

Shimizu K, Koizumi S, Hatamachi T, Yoshida H, Komai S, Kodama T, Kitayama Y. Structural investigations of functionalized mesoporous silica-supported palladium catalyst for Heck and Suzuki coupling reactions. J Catal. 2004;228:141–51.

Horniakova J, Raja T, Kubota Y, Sugi Y. Pyridine-derived palladium complexes immobilized on ordered mesoporous silica as catalysts for Heck-type reactions. J Mol Catal A Chem. 2004;217:73–80.

Crudden CM, Sateesh M, Lewis R. Mercaptopropyl-modified mesoporous silica: a remarkable support for the preparation of a reusable, heterogeneous palladium catalyst for coupling reactions. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:10045–50.

Han P, Zhang H, Qiu X, Ji X, Gao L. Palladium within ionic liquid functionalized mesoporous silica SBA-15 and its catalytic application in room-temperature Suzuki coupling reaction. J Mol Catal A Chem. 2008;295:57–67.

Zhi J, Song D, Li Z, Lei X, Hu A. Palladium nanoparticles in carbon thin film-lined SBA-15 nanoreactors: efficient heterogeneous catalysts for Suzuki–Miyaura cross coupling reaction in aqueous media. Chem Commun. 2011;47:10707–9.

Oliveira RL, He W, Gebbink RJK, de Jong KP. Palladium nanoparticles confined in thiol-functionalized ordered mesoporous silica for more stable Heck and Suzuki catalysts. Catal Sci Technol. 2015;5:1919–28.

Hoshiya N, Shimoda M, Yoshikawa H, Yamashita Y, Shuto S, Arisawa M. Sulfur modification of Au via treatment with piranha solution provides low-Pd releasing and recyclable Pd material, SAPd. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:7270–2.

Hoshiya N, Shuto S, Arisawa M. The actual active species of sulfur-modified gold-supported palladium as a highly effective palladium reservoir in the Suzuki–Miyaura coupling. Adv Synth Catal. 2011;353:743–8.

I Xamena FXL, Abad A, Corma A, Garcia H. MOFs as catalysts: Activity, reusability and shape-selectivity of a Pd-containing MOF. J Catal. 2007;250:294–8.

Zhang L, Su Z, Jiang F, Zhou Y, Xu W, Hong M. Catalytic palladium nanoparticles supported on nanoscale MOFs: a highly active catalyst for Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling reaction. Tetrahedron. 2013;69:9237–44.

Huang SL, Jia AQ, Jin GX. Pd(diimine)Cl2 embedded heterometallic compounds with porous structures as efficient heterogeneous catalysts. Chem Commun. 2013;49:2403–5.

Pascanu V, Hansen PR, Bermejo Gómez A, Ayats C, Platero-Prats AE, Johansson MJ, Pericàs MÁ, Martín-Matute B. Highly functionalized biaryls via Suzuki–Miyaura cross‐coupling catalyzed by Pd@MOF under batch and continuous flow regimes. Chem Sus Chem. 2015;8:123–30.

Chen L, Gao Z, Li Y. Immobilization of Pd(II) on MOFs as a highly active heterogeneous catalyst for Suzuki–Miyaura and Ullmann-type coupling reactions. Catal Today. 2015;245:122–8.

Li Y, El-Sayed MA. The effect of stabilizers on the catalytic activity and stability of Pd colloidal nanoparticles in the Suzuki reactions in aqueous solution. J Phys Chem B. 2001;105:8938–43.

Pittelkow M, Moth-Poulsen K, Boas U, Christensen JB. Poly(amidoamine)-dendrimer-stabilized Pd(0) nanoparticles as a catalyst for the Suzuki reaction. Langmuir. 2003;19:7682–4.

Gopidas KR, Whitesell JK, Fox MA. Synthesis, characterization, and catalytic applications of a palladium-nanoparticle-cored dendrimer. Nano Lett. 2003;3:1757–60.

Narayanan R, El-Sayed MA. Effect of colloidal catalysis on the nanoparticle size distribution: Dendrimer-Pd vs PVP-Pd nanoparticles catalyzing the Suzuki coupling reaction. J Phys Chem B. 2004;108:8572–80.

Garcia-Martinez JC, Lezutekong R, Crooks RM. Dendrimer-encapsulated Pd nanoparticles as aqueous, room-temperature catalysts for the Stille reaction. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:5097–103.

Lemo J, Heuzé K, Astruc D. Synthesis and catalytic activity of DAB-dendrimer encapsulated Pd nanoparticles for the Suzuki coupling reaction. Inorg Chim Acta. 2006;359:4909–11.

Diallo AK, Ornelas C, Salmon L, Ruiz Aranzaes J, Astruc D. “Homeopathic” catalytic activity and atom-leaching mechanism in Miyaura-Suzuki reactions under ambient conditions with precise dendrimer-stabilized Pd nanoparticles. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:8644–8.

Ogasawara S, Kato S. Palladium nanoparticles captured in microporous polymers: a tailor-made catalyst for heterogeneous carbon cross-coupling reactions. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:4608–13.

Deraedt C, Salmon L, Etienne L, Ruiz J, Astruc D. “Click” dendrimers as efficient nanoreactors in aqueous solvent: Pd nanoparticle stabilization for sub-ppm Pd catalysis of Suzuki–Miyaura reactions of aryl bromides. Chem Commun. 2013;49:8169–71.

Deraedt C, Salmon L, Astruc D. “Click” dendrimer-stabilized palladium nanoparticles as a Green catalyst down to parts per million for efficient C-C cross-coupling reactions and reduction of 4-nitrophenol. Adv Synth Catal. 2014;356:2525–38.

Ding SY, Gao J, Wang Q, Zhang Y, Song WG, Su CY, Wang W. Construction of covalent organic framework for catalysis: Pd/COF-LZU1 in Suzuki-Miyaura coupling reaction. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:19816–22.

Puthiaraj P, Pitchumani K. Palladium nanoparticles supported on triazine functionalised mesoporous covalent organic polymers as efficient catalysts for Mizoroki-Heck cross coupling reaction. Green Chem. 2014;16:4223–33.

Pachfule P, Panda MK, Kandambeth S, Shivaprasad SM, Díaz DD, Banerjee R. Multifunctional and robust covalent organic framework-nanoparticle hybrids. J Mater Chem A. 2014;2:7944–52.

Mullangi D, Nandi S, Shalini S, Sreedhala S, Vinod CP, Vaidhyanathan R. Pd loaded amphiphilic COF as catalyst for multi-fold Heck reactions, CC couplings and CO oxidation. Sci Rep 2015;5:10876.

Gonçalves RS, de Oliveira AB, Sindra HC, Archanjo BS, Mendoza ME, Carneiro LS, Buarque CD, Esteves PM. Heterogeneous catalysis by covalent organic frameworks (COF): Pd(OAc)2@COF-300 in cross-coupling reactions. Chem Cat Chem. 2016;8:743–50.

Zhang P, Weng Z, Guo J, Wang C. Solution-dispersible, colloidal, conjugated porous polymer networks with entrapped palladium nanocrystals for heterogeneous catalysis of the Suzuki-Miyaura coupling reaction. Chem Mater. 2011;23:5243–9.

Li B, Guan Z, Wang W, Yang X, Hu J, Tan B, Li T. Highly dispersed Pd catalyst locked in knitting aryl network polymers for Suzuki-Miyaura coupling reactions of aryl chlorides in aqueous media. Adv Mater. 2012;24:3390–5.

Wang ZJ, Ghasimi S, Landfester K, Zhang KA. Photocatalytic suzuki coupling reaction using conjugated microporous polymer with immobilized palladium nanoparticles under visible light. Chem Mater. 2015;27:1921–4.

Shunmughanathan M, Puthiaraj P, Pitchumani K. Melamine-based microporous network polymer supported palladium nanoparticles: a stable and efficient catalyst for the sonogashira coupling reaction in water. Chem Cat Chem. 2015;7:666–73.

Seto H, Morii T, Yoneda T, Murakami T, Hoshino Y, Miura Y. Preparation of palladium-loaded polymer nanoparticles with catalytic activity for hydrogenation and Suzuki coupling reactions. Chem Lett. 2013;42:301–3.

Seto H, Yoneda T, Morii T, Hoshino Y, Miura Y, Murakami T. Membrane reactor immobilized with palladium-loaded polymer nanogel for continuous-flow Suzuki coupling reaction. AIChE J. 2015;61:582–9.

Varga I, Gilanyi T, Meszaros R, Filipcsei G, Zrinyi M. Effect of cross-link density on the internal structure of poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) microgels. J Phys Chem B. 2001;105:9071–6.

Fänger C, Wack H, Ulbricht M. Macroporous poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) hydrogels with adjustable size “cutoff” for the efficient and reversible immobilization of biomacromolecules. Macromol Biosci. 2006;6:393–402.

Matsumoto H, Seto H, Akiyoshi T, Shibuya M, Hoshino Y, Miura Y. Macroporous gel with a permeable reaction platform for catalytic flow synthesis. ACS Omega. 2017;2:8796–802.

Narayanan R, El-Sayed MA. Effect of catalysis on the stability of metallic nanoparticles: Suzuki reaction catalyzed by PVP-palladium nanoparticles. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:8340–7.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP16H01036 in Precisely Designed Catalysts with Customized Scaffolding. This work was also supported in part by funds from the Hosokawa Powder Technology Foundation and the Central Research Institute of Fukuoka University (No. 175009). The support from the Izumi Science and Technology Foundation was greatly appreciated. We thank Prof. K. Ohto, Assoc. Prof. H. Kawakita, Mr. Y. Ueda, and Mr. Y. Takaoka at Saga University for their assistance in providing access to the ICP-AES.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Matsumoto, H., Akiyoshi, T., Hoshino, Y. et al. Size-tuned hydrogel network of palladium-confining polymer particles: a highly active and durable catalyst for Suzuki coupling reactions in water at ambient temperature. Polym J 50, 1179–1186 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41428-018-0102-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41428-018-0102-2