Abstract

The most effective way to enhance the dissipation-free supercurrent in the presence of a magnetic field for type II superconductors is to introduce defects that act as artificial pinning centers (APCs) for vortices. For instance, the in-field critical current density of doped BaFe2As2 (Ba122), one of the most technologically important Fe-based superconductors, has been improved over the last decade by APCs created by ion irradiation. The technique of ion irradiation has been commonly implemented to determine the ultimate superconducting properties. However, this method is rather complicated and expensive. Here, we report a surprisingly high critical current density and strong pinning efficiency close to the crystallographic c-axis for a K-doped Ba122 epitaxial thin film without APCs, achieving performance comparable to ion-irradiated K-doped Ba122 single crystals. Microstructural analysis reveals that the film is composed of columnar grains with widths of approximately 30–60 nm. The grains are rotated around the b- (or a-) axis by 1.5° and around the c-axis by −1°, resulting in the formation of low-angle grain boundary networks. This study demonstrates that the upper limit of in-field properties reached in ion-irradiated K-doped Ba122 is achievable by grain boundary engineering, which is a simple and industrially scalable manner.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Significant progress in the growth of Fe-based superconductor (FBS) thin films has been achieved over the past decade. As a result, high-quality, epitaxial thin films of technologically important FBS [e.g., Fe(Se,Te), doped AeFe2As2 (Ae: alkaline earth elements) and doped LnFeAsO (Ln: lanthanoid elements)] are realized on different kinds of single-crystalline substrates and technical substrates1,2,3,4,5 except for (Ba,K)Fe2As2 (K-doped Ba122). The realization of epitaxial K-doped Ba122 has been challenging due to the difficulty in controlling volatile potassium. We have recently succeeded in growing K-doped Ba122 epitaxial thin films on fluoride substrates6, which gives a great opportunity to investigate their electrical transport properties. Our preliminary study shows that grain boundaries (GBs) are present in K-doped Ba122 despite no sign of weak-link behaviors.

GB with a misorientation angle larger than the critical angle θc ~ 9° becomes a detrimental defect to the critical current for most FBS3,7,8. On the other hand, GBs with a small misorientation angle less than θc do not impede the supercurrent flow. Rather, dislocation arrays in low-angle GBs (LAGBs) contribute to flux pinning3,7,8, leading to improvements in the critical current properties of FBS thin films. Indeed, several studies have shown a proof of principle of this concept by growing P- and Co-doped Ba122 thin films on technical substrates with oxide buffer layers having a different in-plane spread prepared by ion beam-assisted deposition (IBAD)9,10. In both compounds, the larger the texture spread of Ba122 within θc, the higher the critical current density Jc, typically a few MA cm−2 at 4 K. Additionally, Jc for the applied field parallel to the crystallographic c-axis (H||c) is similar to or even higher than that for H||ab10,11. It was later demonstrated that enhanced pinning performance is due to LAGBs acting as flux pinning centers12.

However, other well-known techniques, such as irradiation with protons and heavy ions, produce either isotropic or anisotropic defects (i.e., artificial pinning centers, APCs) significantly enhanced Jc above the value obtained by the aforementioned GB engineering. For instance, a SmFeAs(O,F) single crystal with columnar defects produced by heavy-ion irradiation exhibits a high self-field Jc of 18–20 MA cm−2 at 5 K, which is approximately 9–10 times the Jc of the pristine sample13. Similarly, Ba0.6K0.4Fe2As2 single crystals with point defects created by 3-MeV proton irradiation show a self-field Jc of 11 MAcm−2 at 2 K, which is ~4.6 times the Jc of the pristine sample14. Recently, a Ba0.6K0.4Fe2As2 single crystal irradiated by 320-MeV Au ions shows a very high self-field Jc of over 20 MA cm−2 at 2 K15, corresponding to a 12% depairing current density Jd~166 MA cm−2 16.

Here, we report a surprisingly high self-field Jc of 14.4 MA cm−2 at 4 K and a strong pinning efficiency close to the crystallographic c-axis for the K-doped Ba122 epitaxial thin film with LAGB networks. The pinning force density Fp for H||c exceeds 200 GN m−3 at 4 K and above 6 T, which is at a level comparable to the K-doped Ba122 single crystal with Pb-ion irradiation17.

Materials and methods

Thin film growth

K-doped Ba122 thin films were grown on CaF2(001) at 395 °C, a slightly lower temperature than in our previous investigation, by custom designed molecular beam epitaxy using solid sources of Fe, As, Ba and In-K alloy6. Here, we used an In–K alloy rather than pure K because of the good controllability of the K content in the film as well as safety issues. The CaF2 substrate was fixed on the sample holder using Ag paste to ensure good thermal conduction. Prior to deposition, the substrate was heated to 600 °C, kept at this temperature for 15 min for thermal cleaning, and subsequently cooled to 395 °C. The compositions of all fluxes except for As were monitored in situ by electron impact emission spectrometry (Ba and Fe) and atomic absorption spectrometry (K). The obtained real-time information was fed back to a personal computer that controls the proportional–integral–differential (PID) of the resistive heaters. The As flux was provided constantly during growth. Compared with our previous films, the growth parameters (i.e., deposition temperature and evaporation rate for each flux) were fully optimized, as evidenced in Supplementary Fig. S1. Unlike our previous investigation, no impurity phases were observed. Additionally, the average full width at half maximum value of the 103 ϕ-scan is 1.1°, which is smaller than our previous film6.

Microstructural analysis by transmission electron microscopy

Cross-sectional samples were prepared by a focused ion beam. Scanning transmission electron microscopy observations were performed by a TEM (JEOL ARM-200F) operated at an acceleration voltage of 200 kV. TEM-based scanning precession electron diffraction (PED) analysis was performed by TEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific Tecnai G2 F20 equipped with NanoMEGAS ASTAR system) operated at an acceleration voltage of 200 kV. Details of crystal orientation mapping based on PED are described in ref. 18. In this PED analysis, the convergence semiangle of the incident electron beam was 1 mrad, and the precession angle was 0.55°. The crystal orientation at each measurement point was determined by matching the PED pattern with template patterns pregenerated from the crystal structural data of K-doped Ba12219 and CaF220. β and γ are defined as the angles between [001]CaF2 and [001]K-doped Ba122 and [100] (or [010]) CaF2 and [100] (or [010]) K-doped Ba122, respectively. Note that the β and γ values in this measurement include an uncertainty of ~0.4°, which was estimated from the standard deviation of crystal orientation determination on the CaF2 substrate.

Electrical transport measurements

A small bridge 38 μm wide and 1 mm long was fabricated by laser cutting. The sample was mounted on a rotator holder in the maximum Lorentz force configuration. The angle θ is measured from the crystallographic ab-plane. Current–Voltage (I–V) characteristics were measured by a 4-probe method in a commercial physical property measurement system [(PPMS) Quantum Design]. The upper critical fields Hc2 were defined as 90% of the normal state resistivity. The irreversibility fields Hirr were defined as the intersection between the resistivity traces and the resistivity criterion of 10−5 mΩcm. An electric field criterion of 1 μV/cm is used to estimate Jc.

Magnetic measurements

Magnetization measurements were performed on the rectangular-shaped sample using a superconducting quantum interference device magnetometer [SQUID VSM, (MPMS3) Quantum Design]. The temperature dependence of susceptibility was measured with a magnetic field of 1 mT applied parallel to the ab-plane. Magnetic Jc was determined using the Bean model from the field dependence of magnetization curves.

Results

Microstructure

As revealed by structural characterization using X-ray diffraction, K-doped Ba122 was phase-pure and epitaxially grown on CaF2(001) (Supplementary Fig. S1). To evaluate the nanostructure of the grain boundaries, a cross section was observed by scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM, Fig. 1a) and analyzed by TEM-based scanning PED. The incident direction of the electron beam is approximately parallel to the [110] direction of the CaF2(001) substrate. An annular dark-field (ADF) image in Fig. 1a shows columnar grains growing in the z direction, which is more clearly seen in a virtual dark-field image of the 008 reflection (Fig. 1b). The width of columnar grains is 30–60 nm. The epitaxial relationship is revealed as (001)[110]K-doped Ba122 || (001)[100]CaF2 by the PED patterns (Fig. 1c, d), which is consistent with the structural characterization by X-ray diffraction (Supplementary Fig. S1). Crystal rotations of K-doped Ba122 around the b-axis (equivalent to the a-axis) and the c-axis were calculated from the crystal orientation data separately and are plotted as two-dimensional maps in Fig. 1e, f. For clarity, the crystal rotation angles β (around the b- and a-axis) and γ (around the c-axis) with respect to CaF2 are shown in Fig. 1g, h. As clearly seen in the line profiles (Fig. 1i), the average grain rotation around the b- (or a-) axis is \({\Delta}\beta _{{{{\mathrm{average}}}}} = 1.5^ \circ\) and around the c-axis is \({\Delta}\gamma _{{{{\mathrm{average}}}}} = - 1^ \circ\) with respect to the ideal values (i.e., Δβ = β − βideal, where βideal is 0°, and Δγ = γ – γideal, where γideal is 45°), resulting in the formation of LAGB networks. As seen in Supplementary Fig. S2, the [001] of K-doped Ba122 was tilted toward \(\left[ {0\bar 10} \right]\) in our coordinate system. The distribution of β over the 2880 points shows that a large fraction is located between 0° and 3.5° with a peak of 1.5° (Supplementary Fig. S2). For completeness, the distribution of γ is also shown in Supplementary Fig. S3. This fact reflects the angular dependence of Jc measurements, which will be discussed later.

a Cross-sectional view obtained by ADF-STEM. b Virtual dark-field image of the 008 reflection of K-doped Ba122. c Typical PED patterns extracted from the K-doped Ba122 thin film (red cross in b) and (d), the CaF2 substrate (green cross in b). e β rotation map and (f), γ rotation map obtained from the K-doped Ba122 thin film. The z-axis shows the distance from the interface between K-doped Ba122 and CaF2, the same direction as shown in a. The ideal angles, 0° and 45°, are defined as light-green and red color in (e) and (f), respectively. g Schematic illustrations of the crystal rotation angles β (around the [100]-axis) and (h) and γ (around the [001]-axis) with respect to CaF2 as the reference. i Line profiles of β rotation and γ rotation extracted along the black broken lines in (e) and (f), respectively. The lines of β = 0° and γ = 45° are marked for comparison.

Resistivity measurements

Tc,90, defined as 90% of the normal state resistivity, of our K-doped Ba-122 thin film is 35.2 K (Supplementary Fig. S4). The zero-resistivity temperature Tc,0 is 33 K, corresponding to the onset temperature of the diamagnetic signal measured by the temperature dependence of susceptibility. Therefore, the transition width, defined as Tc,90–Tc,0, is 2.2 K.

To determine the upper critical field Hc2 and the irreversibility field Hirr, the temperature dependence of resistivity was measured in the field up to 16 T (Fig. 2a, b). As the applied magnetic field increases, a clear shift of Tc to lower temperatures together with a broadening of the superconducting transition is observed for both main crystallographic orientations. The broadening of the transition is more obvious for H||c than H||ab; however, such broadening is not as significant compared with LnFeAsO21 due to the weak thermal fluctuation. It is also worth mentioning that the foot structure in the vicinity of zero resistance arising from the presence of high-angle GBs, previously observed in ref. 22, is not present here. Such a foot structure is also due to poor connectivity. The temperature dependence of the upper critical field Hc2 and the irreversibility field Hirr are summarized in Fig. 2c. The slopes of Hc2 in the field range 0 ≤μ0H≤ 2 T are −20.1 TK−1 and −11.5 TK−1 for H||ab and ||c, respectively. These values are much higher than those of a single crystal23. Another feature is that the slope of the Hirr–line for H||c changes at approximately 2 T (inset of Fig. 2c), which is reminiscent of REBa2Cu3O7 (RE: rare earth elements, REBCO) thin films with c-axis correlated defects24. To identify the matching field, μ0Hirr is plotted as a function 1–T/Tirr, where Tirr is the irreversibility temperature (Fig. 2d). The slope of the μ0Hirr-line changes from 1.77 to 1.02 at 2 T.

a Resistivity curves for H parallel to the crystallographic c-axis and (b) H||ab-plane. The field increment was 2 T from 2 to 16 T. Below 2 T, measurements were conducted at 0, 0.5, 1, and 2 T. c Both Hc2 and Hirr are plotted as a function of temperature. The solid symbols represent Hc2, and the open symbols show Hirr. For H||c, the slope of Hirr changes by approximately 2 T, as indicated by the arrow. d Logarithmic presentation of Hirr vs. 1–T/Tirr, where Tirr is the irreversibility temperature at the self-field. The slope changes at 2 T, corresponding to the matching field.

Pinning potential

To obtain the activation energy U0 for vortex motion at given fields, linear fits of the Arrhenius plots for the resistivity curves are conducted (Fig. 3a, b). Based on the thermally activated flux-flow model25, the slope of the linear fits corresponds to −U0. In fact, on the assumption of the linear temperature dependence, U(T,H) = U0(H)(1–T/Tc), the following two formulae, lnρ(T,H) = lnρ0(H)–U0(H)/T and lnρ0(H) = lnρ0f + U0(H)/Tc, (derived from ρ(T,H) = ρ0fexp[–U(T,H)/T] = ρ0fexp[–U0(H)(1–T/Tc)/T]), are obtained with ρ0f being the prefactor. As seen in Fig. 3c, the activation energy U0 for both H||c and ||ab shows the same power law relation H−α in low fields up to 2 T: the exponent α is ~0.05–0.07, which indicates that single vortex pinning prevails. In this regime, U0 for both directions is 12,000–13,000 K, whereas the respective values of the Ba0.72K0.28Fe2As2 single crystal with Tc = 32 K (i.e., underdoped sample) for H||ab and ||c at 1 T are 8500 K and 5000 K26. Above 2 T, for H||ab, α ~0.5 is consistent with a plastic pinning regime27. On the other hand, for H||c, α is 0.68, which is located between 0.5 and 1, where the exponent α = 1 is the theoretical prediction for collective pinning28. It is interesting to note that for the high field regime (i.e., 13–16 T) U0 of our film is comparable to that of single crystals26.

The relationship between ln[ρ0] and U0 for both orientations is shown in Fig. 3d, where the slope of the linear fits corresponds to 1/Tc. The respective Tc for H||c and ||ab are 35.4 K and 35.5 K, which is close to Tc,90. This perfect scaling justifies the initial assumption of U(T, H) = U0(H)(1–T/Tc) in a wide range of temperatures.

Field dependence of J c obtained from the transport and magnetization measurements

Figure 4a shows the in-field Jc properties for the K-doped Ba122 thin film measured by the I–V (or current density J—electric field E) characteristics at various temperatures. E–J curves for H||c are shown in Supplementary Fig. S5. At 30 K for both H||c and ||ab, Jc gradually decreases with increasing fields. However, Jc below 25 K is almost insensitive to applied magnetic fields, and a high Jc above 2 × 105 A cm−2 is maintained over the entire investigated field range. The most striking feature is that Jc for H||c exceeds that for H||ab with decreasing temperature, opposite to the expected intrinsic behavior related to the anisotropy of Hc2. Similar features with inverse anisotropy caused by strong c-axis correlated defects were previously observed, for instance, in Co-doped Ba12229 and REBCO24,30,31. These results infer that strong c-axis pinning is active at T≤ 25 K. It is worth mentioning that the Jc peak for H||c is prominent at high temperatures for REBCO, but it is strongly suppressed with decreasing temperature32, which is different from FBS.

a Jc-H characteristics for both main orientations obtained from the transport measurements. The solid symbols represent H || c, and the open symbols show H||ab. b Field dependence of Jc evaluated from the magnetization measurements using the extended Bean model. c Temperature dependence of Jc for several applied fields H||c. d Field dependence of Fp calculated from (a).

To prevent overheating of the contact leads/pads and possible sample damage, the E–J characterization was limited at low fields and temperatures. Hence, for completeness, the field dependence of magnetization to extract Jc was measured on a rectangular sample cut from the same film used for transport measurements over a wider temperature range (Supplementary Fig. S6). Jc calculated from the Bean model is shown in Fig. 4b. Except for 28 K, Jc has a weak field dependence, which is consistent with the transport Jc. At 4 K, self-field Jc reaches 14.4 MA cm−2, corresponding to ~9% of the depairing current density Jd16. The temperature dependence of Jc measured by electrical transport measurements well follows the magnetization Jc (Fig. 4c), although the electric field criterion Ec of the former is higher than that of the latter. The data at 30 K slightly deviating from the trend are likely due to the fluctuations close to Tc.

The field dependence of Fp calculated from Fig. 4a is summarized in Fig. 4d. Because of the presence of strong c-axis pinning at T ≤ 25 K, the maximum Fp is always recorded for H||c within our experimental condition (i.e., up to 16 T).

Angle dependence of J c obtained from the transport measurement

To obtain a better understanding of the pinning efficiency, measurements of the angular dependences of Jc were conducted at various temperatures and field strengths (Fig. 5). For all fields, the Jc peaks around H||c (θ = 90°) are weak at 30 K; however, they become intense at T≤ 25 K. The peak position of Jc around H||c is ~4° away from the c-axis, indicating that “the correlated defects” are slightly tilted. This is because the columnar grains of K-doped Ba122, which creates LAGBs along the grains, grew unidirectionally at an incline of a few degrees with respect to the substrate normal. To clearly see the effect of correlated defects on Jc, Jc anisotropy defined as Jc/Jcab, where Jcab is Jc at θ = 180°, is plotted at the fixed magnetic field (Fig. 5e–g). The black dashed lines are positioned at 94° to clearly see the Jc peaks. At 4 T and 30 K, Jc/Jcab is approximately 0.5 for H||c (Fig. 5e), increasing to ~1.6 at low temperatures. This is a clear indication that the strong pinning around H||c is activated between 30 and 25 K. As increasing applied magnetic fields, a full evolution of the angular dependence of Jc/Jcab can be observed from a roughly regular behavior with a maximum at 180° for H||ab (e.g., 16 T and 25 K) to an almost isotropic behavior (e.g., 10 T and 25 K as well as 16 T and 20 K) and finally to a behavior strongly affected by c-axis correlated pinning at the lowest temperatures.

The measurement temperatures were (a), 30 K, (b), 25 K, (c), 20 K, and (d), 15 K. Angles of θ = 90° and 180° correspond to H||c and ||ab, respectively. Angle dependence of Jc normalized by Jc for H||ab (Jcab) measured at (e) 4 T, (f) 10 T, and (g) 16 T. The dashed lines are located at θ = 94° to clearly see the Jc peaks.

Discussions

Through microstructural analyses and electrical transport measurements, a “c-axis correlated defect” in our K-doped Ba122 thin film is identified as a low-angle grain boundary (LAGB). On the assumption that the mean distance d of correlated pinning is identical to that of the width of K-doped Ba122 grains (i.e., 30–60 nm), the matching field Bϕ~ϕ0/d2 is approximately 2 T at which a kink of Hirr is observed (Fig. 2c, d, ϕ0 being the flux quantum). As shown in Fig. 5, this pinning is strongly temperature dependent, which is presumably due to the crossover between the in-plane coherence length of K-doped Ba122 and the defect size. The correlated GB pinning and networks improve not only self-field Jc but also in-field Jc for H close to the c-axis. Consequently, the anisotropy of Jc is inverted with respect to Hc2. A similar observation was reported in ref. 33, where the GBs between columnar grains in MgB2 thin films grown by e-beam evaporation worked as pinning centers.

The tilted growth of K-doped Ba122 is presumably due to the geometrical configuration of the deposition sources together with the deposition without rotating substrates. In our setup, vapor flux arrives at the substrate with an oblique angle. Additionally, adatoms are expected to diffuse relatively slowly on the substrate, since the substrate temperature was low compared with the incongruent melting and decomposition temperatures of K-doped Ba122 (917 °C and 988 °C, respectively)34. Hence, the shadowing effect35, which limits the formation of new nuclei during the deposition behind initially formed nuclei, is pronounced, resulting in inclined columnar growth.

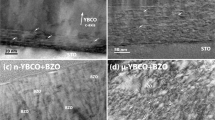

A pinning force density Fp of 114 GN m−3 is recorded even at 15 K and 14–16 T (obtained from the transport measurement) and exceeds 200 GNm−3 at 4 K and a field above 6 T (the data at 4 K are obtained from the magnetization measurements in Fig. 4b). In Fig. 6, the field dependence of Fp for our K-doped Ba122 thin film is plotted. For comparison, we also plotted the following data of pinning-enhanced Ba122 single crystal and thin films with different dopants: K-doped Ba122 single crystal with Pb-ion irradiation measured at 5 K17, Co-doped Ba122 thin film with large amounts of stacking faults measured at 4.2 K35, Co-doped Ba122 thin film with 3 mol% BaZrO3 (BZO) measured at 5 K36, and P-doped Ba122 with 3 mol% BZO measured at 4.2 K and 15 K37. As seen, up to 4 T, the Fp of our K-doped Ba122 thin film is the highest among the pinning-enhanced Ba122. Although the Fp data above 7 T are missing, the extrapolated value at 9 T for the K-doped Ba122 thin film is comparable to the highest value reported for the Co-doped Ba122 thin film.

The Fp for K-doped Ba122 thin film measured at 4 K and 15 K. The respective Fp at 4 K and 15 K are calculated using the Jc–H data obtained from the magnetic and transport measurements. For comparison, the data of K-doped Ba122 single crystal with Pb-ion irradiation measured at 5 K17, Co-doped Ba122 thin film with a large number of stacking faults measured at 4.2 K36, Co-doped Ba122 thin film with 3 mol% BaZrO3 (BZO) measured at 4.2 K37, and P-doped Ba122 thin film with 3 mol% BZO measured at 4 K and 15 K38 are also plotted.

The large improvement of the superconducting properties of our K-doped Ba122 thin film without APCs is due to the high density of correlated pinning centers created by LAGB networks. Unlike Co- and P-doped Ba122 thin films, the growth temperature of K-doped Ba122 thin film is quite low (~400 °C). This low-temperature synthesis may lead to a small grain size and hence an increase in the density of LAGBs. It is worth mentioning that the dislocation density increases with increasing grain boundary angle. Hence, further improvement of in-field Jc is possible by enlarging the texture spread within the critical angle θc. The grain boundary engineering presented in this study highlights a possible novel approach to improve the superconducting properties, which is a simple and industrially scalable manner.

Conclusion

Herein, we investigated the nanoscale microstructure of a K-doped Ba122 epitaxial thin film grown on CaF2 by molecular beam epitaxy. The nanoscale crystal orientation mapping shows that the film is composed of columnar grains with widths of approximately 30–60 nm. The average grain rotation around the b- (or a-) axis is 1.5° and around the c-axis is −1° with respect to the ideal values, resulting in the formation of low-angle grain boundary networks. LAGB networks are used to realize superior superconducting properties of K-doped Ba122: the pinning force density Fp for H||c exceeds 200 GN m−3 at 4 K and above 6 T, which is comparable to the best performing K-doped Ba122 by ion irradiation.

References

Hiramatsu, H., Katase, T., Kamiya, T. & Hosono, H. Thin film growth and device fabrication of iron-based superconductors. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 81, 011011 (2012).

Li, Q., Si, W. & Dimitrov, I. K. Films of iron chalcogenide superconductors. Rep. Prog. Phys. 74, 124510 (2011).

Iida, K., Hänisch, J. & Tarantini, C. Fe-based superconducting thin films on metallic substrates: Growth, characteristics, and relevant properties. Appl. Phys. Rev. 5, 031304 (2018).

Sakoda, M., Iida, K. & Naito, M. Recent progress in thin film growth of Fe-based superconductors: superior superconductivity achieved by thin films. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 31, 093001 (2018).

Hänisch, J., Iida, K., Hühne, R. & Tarantini, C. Fe-based superconducting thin films-preparation and tuning of superconducting properties. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 32, 093001 (2019).

Qin, D. et al. A. Realization of epitaxial thin films of the superconductor K-doped BaFe2As2. Phys. Rev. Mater. 5, 014801 (2021).

Iida, K., Hänisch, J. & Yamamoto, A. Grain boundary characteristics of Fe-based superconductors. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 33, 043001 (2020).

Hänisch, J. & Iida, K. Superconductivity From Materials Science to Practical Applications 269–302, ch 10 (Springer, 2020).

Katase, T. et al. Biaxially textured cobalt-doped BaFe2As2 films with high critical current density over 1 MA/cm2 on MgO-buffered metal-tape flexible substrates. Appl. Phys. Lett. 98, 242510 (2011).

Sato, H., Hiramatsu, H., Kamiya, T. & Hosono, H. Enhanced critical-current in P-doped BaFe2As2 thin films on metal substrates arising from poorly aligned grain boundaries. Sci. Rep. 6, 36828 (2016).

Xu, Z., Yuan, P., Fan, F., Chen, Y. & Ma, Y. Transport properties and pinning analysis for Co-doped BaFe2As2 thin films on metal tapes. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 31, 055001 (2018).

Iida, K. et al. High-field transport properties of a P-doped BaFe2As2 film on technical substrate. Sci. Rep. 7, 39951 (2017).

Fang, L. et al. Huge critical current density and tailored superconducting anisotropy in SmFeAsO0.8F0.15 by low-density columnar-defect incorporation. Nat. Commun. 4, 2655 (2013).

Taen, T., Ohtake, F., Pyon, S., Tamegai, T. & Kitamura, H. Critical current density and vortex dynamics in pristine and proton-irradiated Ba0.6K0.4Fe2As2. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 28, 085003 (2015).

Takahashi, A. et al. Effects of splyaed columnar defects on critical current density in CaKFe4As4. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 1590, 012015 (2020).

Mishev, V., Nakajima, M., Eisaki, H. & Eisterer, M. Effects of introducing isotropic artificial defects on the superconducting properties of differently doped Ba-122 based single crystals. Sci. Rep. 6, 27783 (2015).

Fang, L. et al. High, magnetic field independent critical currents in (Ba,K)Fe2As2 crystals. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 012601 (2012).

Rauch, E. F. et al. Automated nanocrystal orientation and phase mapping in the transmission electron microscope on the basis of precession electron diffraction. Z. Kristallogr. 225, 103–109 (2010).

Zaikina, J. V. et al. Facile synthesis of Ba1–xKxFe2As2 superconductors via hydride route. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 16932–16939 (2014).

Cheetham, A. K., Fender, B. E. F. & Cooper, M. J. Defect structure of calcium fluoride containing excess anions I. Bragg scattering. J. Phys. C. 4, 3107–3121 (1971).

Jaroszynski, J. et al. Upper critical fields and thermally-activated transport NdFeAsO0.7F0.3 single crystal. Phys. Rev. B 78, 174523 (2008).

Lee, N., Jung, S.-G., Kim, D. & Kang, W. Potassium-doped BaFe2As2 superconducting thin films with a transition temperature of 40 K. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 202505 (2010).

Ishida, S. et al. Doping-dependent critical current properties in K, Co, and P-doped BaFe2As2 single crystals. Phys. Rev. B 95, 014517 (2017).

Horide, T. et al. Influence of matching field on critical current density and irreversibility temperature in YBa2Cu3O7 films with BaMO3 (M=Zr, Sn, Hf) nanorods. Appl. Phys. Lett. 108, 082601 (2016).

Palstra, T. T. M., Batlogg, B., Schneemeyer, L. F. & Waszczak, J. V. Thermally activated dissipation in Bi2.2Sr2Ca0.8Cu2O8+δ. Phys. Rev. Lett. 61, 1662–1665 (1989).

Wang, X.-L. et al. Very strong intrinsic flux pinning and vortex avalanches in (Ba,K)Fe2As2 superconducting single crystals. Phys. Rev. B 82, 024525 (2010).

Geshkenbein, V., Larkin, A., Feigel’man, M. & Vinokur, V. Flux pinning and creep in high-Tc superconductors. Phys. C. 162-164, 239–240 (1989).

Blatter, G., Feigel’man, M. V., Geshkenbin, V. B., Larkin, A. I. & Vinokur, V. M. Vortices in high-temperature superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 66, 1125–1388 (1994).

Tarantini, C. et al. Strong vortex pinning in Co-doped BaFe2As2 single crystal thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 142510 (2010).

Matsui, H. et al. 4-fold enhancement in the critical current density of YBa2Cu3O7 films by practical ion irradiation. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 232601 (2012).

Opherden, L. et al. Large pinning forces and matching effects in YBa2Cu3O7-δ thin films with Ba2Y(Nb/Ta)O6 nano-precipitates. Sci. Rep. 6, 21188 (2016).

Xu, A. et al. Broad temperature pinning study of 15 mol.% Zr-added (Gd,Y)-Ba-Cu-O MOCVD coated conductors. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 25, 6603105 (2015).

Kitaguchi, H. et al. MgB2 films with very high critical current densities due to strong grain boundary pinning. Appl. Phys. Lett. 85, 2842–2844 (2004).

Sun, G. L. et al. Single crystal growth and effect of doping on structural, transport and magnetic properties of A1-xKxFe2As2 (A=Ba, Sr). J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 24, 1773–1785 (2011).

Dirks, A. G. & Leamy, H. J. Columnar microstructure in vapor-deposited thin films. Thin Solid Films 47, 219–233 (1977).

Yuan, P. et al. Vortex pinning properties in Co-doped BaFe2As2 thin films with a high critical current density over 2 MA cm-2 at 9 T. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 30, 025001 (2016).

Lee, J. et al. High critical current density over 1 MAcm-2 at 13 T in BaZrO3 incorporated Ba(Fe,Co)2As2 thin film. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 30, 085006 (2017).

Miura, M. et al. Enhanced critical current density in BaFe2(As0.66P0.33)2 nanocomposite superconducting films. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 32, 064005 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Wai-Kwong Kwok (Argonne National Laboratory) for data17, Yanwei Ma (Chinese Academy of Science) for data36, Jongmin Lee and Sanghan Lee (Gwangju Institute of Science and Technology) for data37, and Masashi Miura (Seikei University) for data38. This work was supported by JST CREST Grant Number JPMJCR18J4. A portion of the work was performed at the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory, which was supported by National Science Foundation Cooperative Agreement No. DMR-1644779 and the State of Florida. It was also supported by the US Department of Energy Office of High Energy Physics under grant number DE-SC0018750. This work was also partly supported by the Advanced Characterization Platform of the Nanotechnology Platform Japan sponsored by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.I. and A.Y. designed the study. K.I. and C.T. wrote manuscript together with D.Q., H.S., S.H., M.N., and A.Y. Thin film preparation, structural characterization by XRD, and micro bridge fabrication were carried out by D.Q., M.N., K.I., T.H., and C.T. Microstructural characterization by TEM was performed by C.W., Z.G., H.G., H.S., and S.H., and C.T. conducted in-field electrical transport measurements.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Iida, K., Qin, D., Tarantini, C. et al. Approaching the ultimate superconducting properties of (Ba,K)Fe2As2 by naturally formed low-angle grain boundary networks. NPG Asia Mater 13, 68 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41427-021-00337-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41427-021-00337-5