Abstract

Interfacial phenomena play decisive roles in modern science and technology as the scale of the material shrinks down to a few atomic layers. Such minute nanostructures require a more comprehensive understanding beyond the conventional concepts of interfaces and interfacial phenomena generated at interfaces. From a series of a few-atomic-layer-thick magnetic films, we experimentally demonstrate that, contrary to the common notion, interfacial phenomena require a finite thickness for their full emergence. The layer-thickness dependences reveal that the interfacial Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya interaction (DMI) begins to appear with increasing thickness, and emerges completely at a thickness of 2–3 atomic layers, at which the magnitude is maximized. This result implies that the DMI is suppressed when the “bulk” layer adjacent to the interface is thinner than the threshold thickness. The existence of the threshold thickness indicates the need to refine conventional perspectives on interfacial phenomena, and imposes the lowest structural bound and optimum thickness to maximize interfacial effects for technological applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya interaction (DMI) has attracted much attention because of its peculiar properties for realizing chiral spin structures in magnetic systems with broken inversion symmetry1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10. These chiral spin structures, such as chiral magnetic domain walls1 and magnetic skyrmions2, have been extensively studied as the building blocks of emerging magnetic memory and logic devices3,4. A sufficiently large DMI is essential for highly efficient domain-wall motion via current-induced spin–orbit torques (SOTs)5,6, and for the topological protection of the skyrmion stability7. Hence, extensive efforts have been made to engineer a large DMI and understand its physical origin.

Interest in DMIs has exploded recently because of the discovery of large DMIs at the interfaces of magnetic multilayered systems2,11,12,13. By using these systems, the interfacial DMI strength can be engineered to be strong enough to demonstrate magnetic skyrmions at room temperature2. Beyond the original concept based on the atomic three-site anisotropic superexchange interaction with spin–orbit coupling8,9, recent studies have suggested more comprehensive mechanisms with different governing parameters, such as the work function difference at the interface11, orbital characteristics12,14, charge distribution and interface dipole moment15, and Rashba effect16,17. Although the most decisive parameters and mechanisms are still under debate, it is commonly accepted that the interfacial DMI has to be generated by broken inversion symmetries at the interfaces of heavy metals with large spin–orbit coupling9,13.

Similar to other interfacial effects, it is commonly believed that the interfacial DMI arises at the interface itself, and thus, its strength average over the ferromagnetic layer is inversely proportional to the layer thickness. Therefore, a system with a thinner layer is expected to show a larger DMI strength, as observed by recent studies18,19,20. Such monotonic dependence has been explained by Yang et al.21 based on the atomic-layer-resolved calculations of Pt/Co bilayers by suggesting that the interfacial DMI is generated mostly at the first nearest Co atomic layer to the interface, and thus, the DMI strength is inversely proportional to the layer thickness down to an atomic monolayer. In contrast, another atomic-layer-resolved calculation by Jia et al.22 predicted a significant contribution of the second nearest Co atoms to the DMI in Pt/Co bilayers, resulting in a nonmonotonic dependence of the DMI strength on the layer thickness. Both studies agree that the interfacial phenomena originate from a few atomic layers near the interfaces, but the detailed contributions of each atomic layer to the DMI with the refined DMI mechanisms are still under debate.

In general cases, even at ideal interfaces with abrupt structural boundaries, the crossover between different material properties requires a finite nonzero thickness, over which the interfacial phenomena are generated. Such a crossover thickness might arise from the interactions between the conduction and orbital electrons with a redistribution of the charge and dipole moment10,11,15, or spin chiral mechanisms with the Rashba effect16,17, resulting in off-nearest-site atomic interactions22 beyond the original concept of atomic interactions between the nearest sites.

Materials and methods

Sample fabrication

Two different series of films were prepared. The full-layer stacks of the films are 1.5-nm Ta/3-nm Pt/tCo Co/5-nm W/2-nm AlOx with different ferromagnetic Co-layer thicknesses (tCo) in the range from 0.7 to 1.2 nm for the former Pt/Co/W films and 1.5-nm Ta/3-nm Pt/tCo Co/0.6-nm Cu/5-nm W/2-nm AlOx with different tCo values in the range from 0.3 to 0.8 nm for the latter Pt/Co/Cu/W films. All samples were deposited by dc-magnetron sputtering on Si wafers with a 100-nm-thick SiO2 layer. The lowermost Ta and uppermost AlOx layers are employed as seed and protection layers, respectively. The AlOx layers are formed by natural oxidation after depositing Al layers. To keep a similar film quality, the sputtering conditions were carefully maintained to be the same for all the films with an Ar working pressure of ~2 mTorr and sputtering power of ~10 W. To measure the maximum strength of the SOT efficiency (ε0) and DMI-induced effective magnetic field (HDMI), 20-μm-wide and 350-μm-long microwires were patterned by photolithography and ion-milling processes. To inject electric current into the microwires, 5/100-nm-thick Cr/Au electrodes were deposited by a lift-off process.

Sample characterization

The magnetic anisotropy field (HK) and saturation magnetization (MS) were measured by means of a vibrating sample magnetometer, where HK and MS were estimated by the saturation magnetic field and moment from hard- and easy-axis hysteresis loops, respectively. One can then obtain effective perpendicular magnetic anisotropy (\(K_{\mathrm{U}}^{{\mathrm{eff}}}\)) from the relation \(K_{\mathrm{U}}^{{\mathrm{eff}}} = \mu _0M_{\mathrm{S}}H_{\mathrm{K}}{\mathrm{/}}2\). The measured MS and HK and estimated \(K_{\mathrm{U}}^{{\mathrm{eff}}}\) are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

The values of HDMI and ε0 were quantified by a measurement scheme11 based on the variation in the SOT efficiency (ε) with respect to the in-plane magnetic field (Hx). In this scheme, a domain wall was first created in a magnetic microwire, and then, a domain-wall depinning field (Hdep, in the direction perpendicular to the film plane) from the initial position was detected by sweeping the external magnetic field. By measuring Hdep under the application of several different current densities (J), one can obtain ε via the relations \(\mu _0H_{{\mathrm{dep}}}\left( J \right) = \mu _0H_{{\mathrm{dep}}}^0 + \varepsilon J\), where \(H_{{\mathrm{dep}}}^0\) is the depinning field without an electric current, and εJ corresponds to the effective magnetic field (Heff, in the direction perpendicular to the film plane) caused by the SOT. By repeating these procedures by sweeping Hx, one can obtain an ε–µ0Hx plot, as shown in Fig. 1.

Under the application of an electric current, the damping-like SOT generates the effective magnetic field in the direction of \(\hat m \times \hat s\), where \(\hat m\) is the unit vector of the magnetization inside the domain wall and \(\hat s\) is the unit vector of the spins associated with the SOT23. For the case that J is parallel to the x axis, \(\hat s\) is parallel to the y axis, and therefore, Heff along the Z axis is proportional to the x component (mx) of the magnetization inside the domain wall, i.e., \(H_{{\mathrm{eff}}}\hat z \propto m_x\hat x \times \hat y\). Since µ0Heff = εJ, one can then obtain the relation \(\varepsilon \propto m_x\). By sweeping Hx, the domain wall varies from one Néel-type configuration (mx = −1) to another (mx = 1) through a Bloch-type configuration (mx = 0). Therefore, the ε – µ0Hx plots exhibit the typical behavior of two saturation regimes with the Néel-type domain-wall configurations (ε = ±ε0) across the Bloch-type domain-wall configuration (ε = 0). Since the Bloch-type domain-wall configuration appears when Hx exactly compensates for HDMI (i.e., Hx + HDMI = 0), the x intercept (i.e., ε = 0) indicates the magnitude of HDMI (black vertical line), as shown in Fig. 1. In addition, ε0 is quantified from the saturation values in the Néel-type domain-wall configurations.

Results and discussion

Observation of quick DMI decay with decreasing Co-layer thickness

To demonstrate the existence of a finite thickness for DMI generation, we experimentally examined the DMI strength with respect to tCo. Figure 2 summarizes the measured values of HDMI (a) and ε0 (b) obtained from the plot in Fig. 1 with respect to tCo. The measured HDMI and ε0 are listed in Supplementary Table 1. Due to the interfacial nature, it is expected that both the strengths of the DMI and SOT increase as tCo decreases via an increase in the surface-to-volume ratio6,18,19,24,25. This expectation truly occurs for the case of the SOT, as seen in Fig. 2b, that ε0 increases monotonically as tCo decreases. However, interestingly, a quite distinct behavior occurs for the case of the DMI. Figure 2a shows that HDMI quickly decays in the thinner tCo regime, whereas the typical interfacial behavior of the inverse proportionality appears in the thicker tCo regime. The critical thickness between these two regimes is found to be ~0.8 nm, where the maximum HDMI strength is achieved.

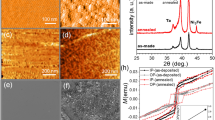

Consideration of possible structural origins

We first examined structural imperfections as the possible origins of this peculiar behavior. Among the possible structural imperfections, the discontinuous island growth of the Co layer is not observed in our films, but rather a continuous crystalline structure of the Co layer appears in a cross-sectional transmission electron microscope (Cs-TEM), which was used to confirm the degree of the continuity and roughness at the interface. The cross-sectional image visualizes a continuous crystalline structure of the Co layer, even for the thinnest case of the Co layer, as shown in Fig. 3a, and the signaling effective magnetic layer remains continuous for this series of films. If the Co layer is discontinuous (see Supplementary Fig. 1), then there is a possibility for a reduction of the DMI strength (see Supplementary Fig. 2) due to the decreasing number of atomic pairs between Co and the atoms of the nonmagnetic material, as described in Supplementary Information. However, a closer look indicates smooth atomic-layer boundaries and clear contrast at the interfaces, as visualized in Fig. 3b, and thus, a reduced number of atomic pairs due to a discontinuous Co layer is unlikely the major origin of the quick HDMI decay.

Structural variation, such as the coherent-to-incoherent transition of crystalline structures26,27, was also examined by the measurement of \(K_{\mathrm{U}}^{{\mathrm{eff}}}\) with respect to tCo. The measurement results (see Supplementary Fig. 3a) indicate that the coherent-to-incoherent transition occurs at approximately tCo ~ 1.2 nm, which is very different from the critical thickness for quick HDMI decay. In addition, \(K_{\mathrm{U}}^{{\mathrm{eff}}}\) exhibits a gradual thickness dependence that is dissimilar to the peculiar HDMI variation. Hence, the coherent-to-incoherent transition associated with the \(K_{\mathrm{U}}^{{\mathrm{eff}}}\) variation is unlikely to share the origin of the quick HDMI decay.

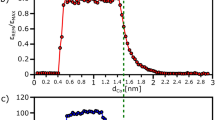

To check whether the quick HDMI decay is possibly caused by a reduction of the magnetically effective thickness \(\left( {t_{{\mathrm{Co}}}^{\mathrm{m}}} \right)\) near the interface, we examined the reduced amount of \(t_{{\mathrm{Co}}}^{\mathrm{m}}\) with respect to the deposited thickness tCo. If W atoms penetrate into the Co layer, then they may alter the properties of the Co layer nearby, forming a reduced thickness (δ) or the so-called dead layer. Even for the continuous Co layers, there may be the possibility of a reduced number of atomic pairs effectively by the penetration of W atoms. For this test, MS was measured by means of a vibrating sample magnetometer. Figure 4a shows the results by plotting MStCo with respect to tCo. The linear dependence between MStCo and tCo manifests that most of the films have similar MS values, considering the magnetic layer volume from \(t_{{\mathrm{Co}}}^{\mathrm{m}}\), as shown in other experiments with Pt/Co trilayer systems28. Then, as guided by the blue linear line of the best fit, the nonzero x intercept indicates the amount of δ, which is quantified as ~0.26 ± 0.01 nm. Notably, δ is noticeably smaller than the critical thickness for the quick HDMI decay. In addition, the roughness/mixing does not exceed the effective magnetic layer thickness (approximately two atomic layers for this sample), as shown in Fig. 3. This situation is similar to the situation depicted on the right side in Supplementary Fig. 1a, with a continuous Co layer even if the W atom penetrates into the Co layer to some extent. Therefore, the results indicate that the mechanism associated with the δ fomation is not directly responsible for the quick HDMI decay.

a Plot of MStCo with respect to tCo (upper label) and \(t_{{\mathrm{Co}}}^{\mathrm{m}}\) (lower label). The blue line shows the linear fit. The x intercept for tCo indicates δ. b Plot of \(Dt_{{\mathrm{Co}}}^{\mathrm{m}}\) with respect to \(t_{{\mathrm{Co}}}^{\mathrm{m}}\). The blue and yellow shaded areas show the thicker and thinner tCo regimes, respectively. The blue horizontal line shows the average value over the thicker tCo regime. c Plot of \(\varepsilon _0t_{{\mathrm{Co}}}^{\mathrm{m}}\) with respect to \(t_{{\mathrm{Co}}}^{\mathrm{m}}\). The blue horizontal line shows the average value over both regimes. In all the plots, the horizontal error bars are the experimental accuracy of the Co-layer thickness, and the vertical error bars are the standard deviation of several repeated measurements.

Analysis with the magnetically effective thickness

To obtain detailed insights into the origin more quantitatively, the DMI strength (D) is estimated by the relation D = µ0HDMIMSλ, where µ0 is the permeability constant and λ is the domain-wall width5. The measured D values are listed in Supplementary Table 1. The values of λ are estimated by the equation of the Bloch-type domain-wall width5,29; i.e., \(\lambda = \left( {A_{{\mathrm{ex}}}{\mathrm{/}}K_{\mathrm{U}}^{{\mathrm{eff}}}} \right)^{1/2}\) under the assumption that the exchange stiffness (Aex) remains constant (=22 pJ/m). We also confirmed that the possible variation in Aex with respect to ferromagnetic layer thickness29 does not change the main trend in the D variation. Then, D is analyzed in terms of \(t_{{\mathrm{Co}}}^{\mathrm{m}}\) (=tCo–δ). The inverse proportionality between D and \(t_{{\mathrm{Co}}}^{\mathrm{m}}\) is examined by plotting \(Dt_{{\mathrm{Co}}}^{\mathrm{m}}\) with respect to \(t_{{\mathrm{Co}}}^{\mathrm{m}}\), as shown in Fig. 4b. This scaled plot is useful for decomposing the surface contribution (DS) and the volume contribution (DV) via the relation \(Dt_{{\mathrm{Co}}}^{\mathrm{m}} = D_{\mathrm{S}} + D_{\mathrm{V}}t_{{\mathrm{Co}}}^{\mathrm{m}}\). Interestingly, the plot again exhibits two different regimes. In the thicker \(t_{{\mathrm{Co}}}^{\mathrm{m}}\) regime (blue area), \(Dt_{{\mathrm{Co}}}^{\mathrm{m}}\) shows a negligible variation with respect to \(t_{{\mathrm{Co}}}^{\mathrm{m}}\), indicating that D has a negligible volume contribution, i.e., DV ≅ 0. Therefore, the surface contribution is mostly responsible for the DMI, i.e., \(Dt_{{\mathrm{Co}}}^{\mathrm{m}} \cong D_{\mathrm{S}}\). In addition, the saturation values of \(Dt_{{\mathrm{Co}}}^{\mathrm{m}}\) show that DS is fully generated in this regime, resulting in the inverse proportionality between D and \(t_{{\mathrm{Co}}}^{\mathrm{m}}\).

On the other hand, in the thinner \(t_{{\mathrm{Co}}}^{\mathrm{m}}\) regime (yellow area), \(Dt_{{\mathrm{Co}}}^{\mathrm{m}}\) becomes smaller than the saturation value. The critical thickness between these two regimes is ~0.55 nm (≅3 atomic layers), which is consistent with the prediction based on the atomic-layer-resolved calculation by Jia et al.22. Notably, the other atomic-layer-resolved calculation by Yang et al.21 can be extended to explain such insufficient DMI generation for the case of an incomplete atomic interface formation with large vacancies (see Supplementary Information), although this case is unlikely for our films with reasonably clear atomic-layer boundaries, as shown in Fig. 3b. It is not easy to quantify the exact contributions of these mechanisms, but both cases suggest that the incomplete generation of the interfacial DMI might be a possible origin of the quick DMI decay in the thinner regime.

The distinct thickness dependences of the DMI and SOT provide another hint to understand the interfacial and bulk phenomena, and the possibility of the independent engineering of the DMI and SOT. In contrast to the DMI that should be generated near the interfaces, the SOT is known to have two sources: at the interfaces via the Rashba effect30 known as the source of the field-like torque, and from the adjacent nonmagnetic layers via the spin-Hall effect24,31 known as the source of the damping-like torque. The plot of \(\varepsilon _0t_{{\mathrm{Co}}}^{\mathrm{m}}\) with respect to \(t_{{\mathrm{Co}}}^{\mathrm{m}}\) (Fig. 4c) shows that \(\varepsilon _0t_{{\mathrm{Co}}}^{\mathrm{m}}\) remains unchanged within the error bars over the whole thickness range. The slight reduction in \(\varepsilon _0t_{{\mathrm{Co}}}^{\mathrm{m}}\) with respect to \(t_{{\mathrm{Co}}}^{\mathrm{m}}\) might be attributed to the decrease in spin current absorption in Co as \(t_{{\mathrm{Co}}}^{\mathrm{m}}\) becomes too thin32. This observation indicates that the SOT is less sensitive to interface formation in our samples, and thus, the damping-like torque is the main source of the SOT originating mainly from the spin-Hall current from the outer nonmagnetic layers in these films. Unlike the SOT in our samples, the DMI is sensitive to the thickness of the atomic layers in the vicinity of the interface, indicating that the quick DMI decay might be attributed not only to the interface characteristics, but also to incomplete DMI generation with Co layers thinner than the critical thickness.

Confirmation with other series films without a reduction of the magnetically effective thickness

To avoid any possible artifacts associated with the mechanisms of the \(t_{{\mathrm{Co}}}^{\mathrm{m}}\) reduction, another series of films with Pt/Co/Cu/W stacks was prepared with different tCo values. In these films, a Cu layer (0.6 nm) was inserted at the Co/W interface to suppress intermixing between the Co and W atoms33. The same measurements were performed on Pt/Co/Cu/W samples, and the measured parameters are listed in Supplementary Table 2. The Co thickness dependence of \(K_{\mathrm{U}}^{{\mathrm{eff}}}\) in the Pt/Co/Cu/W samples is similar to that of the Pt/Co/W samples, as is also shown in Supplementary Fig. 3b. The same typical ε variation with respect to Hx was observed from this series of films, as shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 6a shows a plot of MStCo with respect to tCo for this series of films. It is noteworthy that the x intercept of the linear fit passes close to the origin, indicating that δ is negligibly small, and thus, \(t_{{\mathrm{Co}}}^{\mathrm{m}} \cong t_{{\mathrm{Co}}}\) in these films. Due to the negligibly small δ, this series of films maintains strong perpendicular magnetic anisotropy, even for films with the thinnest tCo down to ~1.5 atomic monolayers. Then, the DMI and SOT are quantified by repeating the same analysis on the data in Fig. 5 as done for the former series of films. The results are shown in Fig. 6b, c with respect to \(t_{{\mathrm{Co}}}^{\mathrm{m}}\). Interestingly, the figures again reproduce the distinct thickness dependence between the DMI and SOT; specifically, the interfacial DMI drops quickly in the thinner \(t_{{\mathrm{Co}}}^{\mathrm{m}}\) regime below 0.4 nm, whereas the SOT remains unchanged over the whole \(t_{{\mathrm{Co}}}^{\mathrm{m}}\) range. The same behaviors exist for both cases with and without the \(t_{{\mathrm{Co}}}^{\mathrm{m}}\) reduction, which confirms that the peculiar thickness dependence of the DMI is not associated with the mechanisms of the \(t_{{\mathrm{Co}}}^{\mathrm{m}}\) reduction.

a Plot of MStCo with respect to tCo (upper label) and \(t_{{\mathrm{Co}}}^{\mathrm{m}}\) (lower label). The blue line shows the linear fit. The x intercept for tCo indicates δ. b Plot of \(Dt_{{\mathrm{Co}}}^{\mathrm{m}}\) with respect to \(t_{{\mathrm{Co}}}^{\mathrm{m}}\). The blue and yellow shaded areas show the thicker and thinner tCo regimes, respectively. The blue horizontal line shows the average value over the thicker tCo regime. c Plot of \(\varepsilon _0t_{{\mathrm{Co}}}^{\mathrm{m}}\) with respect to \(t_{{\mathrm{Co}}}^{\mathrm{m}}\). The blue horizontal line shows the average value over both regimes. In all the plots, the horizontal error bars are the experimental accuracy of the Co-layer thickness, and the vertical error bars are the standard deviation of several repeated measurements.

In summary, we demonstrate the existence of a finite thickness for full DMI generation at interfaces from two different series of films Pt/Co/W and Pt/Co/Cu/W with various Co-layer thicknesses. Both series of films exhibit the same behavior of quick DMI decay with a decrease in the ferromagnetic layer thickness below a threshold thickness. Such a quick DMI decay has to be caused by insufficient DMI generation at interfaces with ferromagnetic layers that are thinner than the threshold. Therefore, the full emergence of the interfacial DMI requires a finite-threshold thickness, in contrast to the commonly accepted concept that the interfacial phenomena are generated exactly at the interfaces. Interestingly, both series of films provide a similar threshold thickness of ~2–3 atomic layers, signaling the possibility of common key mechanisms for DMI generation. These results provide a technological criterion to optimize the DMI strength with a maximum at the threshold thickness. In addition, the distinct behaviors between the DMI and SOT manifest that the DMI is generated in the vicinity of the interface, whereas the SOT is generated mainly by the spin-Hall current from the outer nonmagnetic layers in our series of films. These distinct behaviors provide the perspective of a systematic study on the interfacial DMI and bulk SOT phenomena, providing a method for the independent tuning of the DMI and SOT for spintronic applications.

References

Kim, D.-Y., Kim, D.-H., Moon, J. & Choe, S.-B. Determination of magnetic domain-wall types using Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction-induced domain patterns. Appl. Phys. Lett. 106, 262403 (2015).

Woo, S. et al. Current-driven dynamics and inhibition of the skyrmion Hall effect of ferromagnetic skyrmions in GdFeCo films. Nat. Commun. 9, 959 (2018).

Parkin, S. S. P. & Yang, S.-H. Memory on the racetrack. Nat. Nanotech. 10, 195–198 (2015).

Fert, A., Cros, V. & Sampaio, J. Skyrmions on the track. Nat. Nanotech. 8, 152–156 (2013).

Thiaville, A., Rohart, S., Jué, É., Cros, V. & Fert, A. Dynamics of Dzyaloshinskii domain walls in ultrathin magnetic films. Europhys. Lett. 100, 57002 (2012).

Franken, J. H., Herps, M., Swagten, H. J. M. & Koopmans, B. Tunable chiral spin texture in magnetic domain-walls. Sci. Rep. 4, 5248 (2014).

Sampaio, J., Cros, V., Rohart, S., Thiaville, A. & Fert, A. Nucleation, stability and current-induced motion of isolated magnetic skyrmions in nanostructures. Nat. Nanotech. 8, 839–844 (2013).

Dzyaloshinsky, I. A thermodynamics theory of weak ferromagnetism of antiferromagnetics. J. Phys. Chem. Solid. 4, 241–255 (1958).

Moriya, T. Anisotropic superexchange interaction and weak ferromagnetism. Phys. Rev. 120, 91–98 (1960).

Fert, A. & Levy, P. M. Role of anisotropic exchange interactions in determining the properties of spin-glasses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 44, 1538–1541 (1980).

Park, Y.-K. et al. Experimental observation of the correlation between the interfacial Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction and work function in metallic magnetic trilayers. NPG Asia Mater. 10, 995–1001 (2018).

Kim, S. et al. Correlation of the Dzyaloskinskii-Moriya interaction with Heisenberg exchange and orbital asphericity. Nat. Commun. 9, 1648 (2018).

Soumyanarayanan, A., Reyren, N., Fert, A. & Panagopoulos, C. Emergent phenomena induced by spin-orbit coupling at surfaces and interfaces. Nature 539, 509–517 (2016).

Belabbes, A., Bihlmayer, G., Bechstedt, F., Blügel, S. & Manchon, A. Hund’s rule-driven Dzyaloskinskii-Moriya interaction at 3d-5d interfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 247202 (2016).

Belabbes, A., Bihlmayer, G., Blügel, S. & Manchon, A. Oxygen-enabled control of Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction in ultra-thin magnetic films. Sci. Rep. 6, 24634 (2016).

Kim, K.-W., Lee, H.-W., Lee., K.-J. & Stiles, M. D. Chirality from interfacial spin-orbit coupling effects in magnetic bilayers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 216601 (2013).

Kundu., A. & Zhang, S. Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction mediated by spin-polarized band with Rashba spin-orbit coupling. Phys. Rev. B. 92, 094434 (2015).

Chaurasiya, A. K. et al. Direct observation of interfacial Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction from asymmetric spin-wave propagation in W/CoFeB/SiO2 heterostructures down to sub-nanometer CoFeB thickness. Sci. Rep. 6, 32592 (2016).

Kim., N.-H. et al. Interfacial Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction, surface anisotropy energy, and spin pumping at spin orbit coupled Ir/Co interface. Appl. Phys. Lett. 108, 142406 (2016).

Han, D.-S. et al. Asymmetric hysteresis for probing Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction. Nano Lett. 16, 4438–4446 (2016).

Yang, H., Thiaville, A., Rohart, S., Fert, A. & Chshiev, M. Anatomy of Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction at Co/Pt interfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 267210 (2015).

Jia, H., Zimmermann, B. & Blügel, S. First-principles investigation of chiral magnetic properties in multilayers: Rh/Co/Pt and Pd/Co/Pt. Phys. Rev. B. 98, 144427 (2018).

Emori, S., Bauer, U., Ahn, S.-M., Martinez, E. & Beach, G. S. D. Current-driven dynamics of chiral ferromagnetic domain walls. Nat. Mater. 12, 611–616 (2013).

Emori, S. et al. Spin Hall torque magnetometry of Dzyaloshinskii domain walls. Phys. Rev. B. 90, 184427 (2014).

Belmeguenai, M. et al. Interfacial Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction in perpendicularly magnetized Pt/Co/AlOx ultrathin films measured by Brillouin light spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 91, 180405(R) (2015).

Jungblut, R., Johnson, M. T., Stegge, J., Reinders., A. & Broeder, F. J. A. Orientational and structural dependence of magnetic anisotropy of Cu/Ni/Cu sandwiches: misfit interface anisotropy. J. Appl. Phys. 75, 6424 (1994).

Bruno, P. & Renard, J.-P. Magnetic surface anisotropy of transition metal ultrathin films. Appl. Phys. A. 49, 499–506 (1989).

Bandiera, S., Sousa, R. C., Rodmacq, B. & Dieny, B. Asymmetric interfacial perpendicular magnetic anisotropy in Pt/Co/Pt trilayers. IEEE Magn. Lett. 2, 3000504 (2011).

Metaxas, P. J. et al. Creep and flow regimes of magnetic domain-wall motion in ultrathin Pt/Co/Pt films with perpendicular anisotropy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 217208 (2007).

Miron, I. M. et al. Current-driven spin torque induced by the Rashba effect in a ferromagnetic metal layer. Nat. Mater. 9, 230–234 (2010).

Hoffmann, A. Spin Hall effects in metals. IEEE Trans. Magn. 49, 5172–5193 (2013).

Kim, K.-W. Spin transparency for the interface of an ultrathin magnet within the spin dephasing length. Phys. Rev. B 99, 224415 (2019).

Bandiera, S., Sousa, R. C., Rodmacq, B. & Dieny, B. Enhancement of perpendicular magnetic anisotropy through reduction of Co-Pt interdiffusion in (Co/Pt) multilayers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 142410 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Samsung Science & Technology Foundation (SSTF-BA1802-07, SSTF-BA1501-07) and the National Research Foundations of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT (MSIT) (2015M3D1A1070465). Y.-K.P., K.-W.K., and B.-C.M. were supported by the KIST Institutional Program (No. 2E29410) and the National Research Council of Science & Technology (NST) (No. CAP-16-01-KIST).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, YK., Kim, JS., Nam, YS. et al. Interfacial atomic layers for full emergence of interfacial Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya interaction. NPG Asia Mater 12, 38 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41427-020-0219-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41427-020-0219-6

This article is cited by

-

Multiple Walker breakdowns in magnetic multilayers

Scientific Reports (2022)