Abstract

To mitigate the effect of atmospheric CO2 on global climate change, gas separation materials that simultaneously exhibit high CO2 permeability and selectivity in gas mixtures must be developed. In this study, CO2 transport through midblock-sulfonated block polymer membranes prepared from four different solvents is investigated. The results presented here establish that membrane morphology and accompanying gas transport properties are sensitive to casting solvent and relative humidity. We likewise report an intriguing observation: submersion of these thermoplastic elastomeric membranes in liquid water, followed by drying prior to analysis, promotes not only a substantial change in membrane morphology, but also a significant improvement in both CO2 permeability and CO2/N2 selectivity. Measured CO2 permeability and CO2/N2 selectivity values of 482 Barrer and 57, respectively, surpass the Robeson upper bound, indicating that these nanostructured membranes constitute promising candidates for gas separation technologies aimed at CO2 capture.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Due to their relatively low cost, facile fabrication, and straightforward scale-up, polymer membranes have emerged as a practical alternative to traditional gas separation processes in large-scale industrial applications1. These applications, include separating nitrogen from air2, hydrogen from various refinery and petrochemical process streams3, and CO2 from natural gas4. The development of polymer membranes for effective CO2 removal prior to atmospheric emission has recently become particularly relevant in the wake of global climate change5. An important economic factor that must be considered is the fabrication of polymer membranes possessing high CO2 permeability and high CO2 selectivity compared to other gases in a gas mixture, as well as robust mechanical stability. In this spirit, numerous efforts have focused on identifying such membranes and improving gas separation properties by controlling membrane preparation through the use of (in)organic additives6 and operating temperature7. While a plethora of new membrane materials has been proposed and applied in various gas separation applications at the bench scale, more than 90% of current commercial membranes are manufactured from less than ten polymers, most of which have been in use for decades8. However, few efforts have focused specifically on membrane processing9. Examples in which the choice of casting solvent, for instance, is critical to gas separation efficacy include poly(2,6-dimethyl-1,4-phenylene oxide)10, polysulfone11, polyimides12, and poly(1-trimethylsilyl-1-propyne)13. In such cases, the chemical characteristics and thermal properties of the casting solvent can strongly influence chain packing (and, hence, free volume and/or crystallization)14.

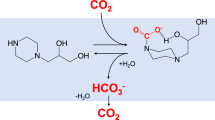

In the present study, we investigate the role of casting solvent on CO2 transport through a novel polymeric material that displays considerable promise for amphoteric (acidic and basic) gas separation15. This amphiphilic material, designated here as TESET to reflect its composition, is a poly[tert-butylstyrene-b-(ethylene-alt-propylene)-b-(styrene-r-styrenesulfonate)-b-(ethylene-alt-propylene)-b-tert-butylstyrene] pentablock polymer, the chemical structure of which is depicted in Scheme 1. This charged block polymer, originally designed to facilitate water transport in applications such as air conditioning, breathable fabrics, and filtration16, is equally suitable for diverse uses ranging from water purification17,18 and pervaporation19 to electroactive media20, antimicrobial surfaces21 and organic photovoltaics22, in addition to gas separation. As a consequence of thermodynamic incompatibility between the blocks, the TESET macromolecule is subject to spontaneous microphase separation, self-organizing into a nanoscale morphology in similar fashion as neutral block copolymers23,24. The charged moieties in a block can, however, form ionic clusters that influence morphological development25. Due to differences in block chemistry (see Scheme 1), the TESET membrane morphology can be templated through judicious choice of solvent or cosolvent26,27. For example, spherical or lamellar + cylindrical morphologies develop when the membrane is cast from single or mixed solvents varying in polarity15,27,28, whereas solvent-vapor annealing can promote the formation of highly ordered and oriented lamellae28.

Although the TESET polymer has been previously examined as a CO2 separation membrane, the measured values of both CO2 permeability and CO2/N2 selectivity are unsatisfactorily low (<30 Barrer and <7, respectively) in the dry state29,30. Endeavors aimed at improving the gas transport properties of TESET membranes are of considerable importance to broaden their potential application in gas separation. Measurements from a previous study, for instance, reveal that the presence of water vapor in the feed can significantly enhance CO2 transport, yielding CO2 permeability and CO2/N2 selectivity values of ~100 Barrer and ~50, respectively15. Here, we employ four solvents varying in polarity to dissolve and cast TESET membranes. The membrane morphologies thereby generated include alternating lamellae, polar spheres positioned on a body-centered-cubic lattice in a nonpolar matrix, disordered polar spheres in a nonpolar matrix, and a combination of cylinders and lamellae. Gas permeation through these membranes is investigated under different relative humidity (RH) conditions. In addition, physical submersion of the membranes in liquid water induces substantial nanostructural transformation31, and the resultant morphologies and gas transport properties are subsequently investigated.

Experimental

In this study, an amphiphilic TESET pentablock polymer (commercialized as Nexar®) was generously provided by Kraton Polymers (Houston, TX). According to the manufacturer, the block weights of the parent (unsulfonated) polymer were 15, 10, and 28 kDa for the T, E, and S blocks, respectively, yielding a number-average molecular weight of 78 kDa. Reagent-grade chloroform, toluene, isopropyl alcohol, cyclohexane, heptane, and tetrahydrofuran were all purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Oslo, Norway) and used as received. For gas permeation tests, a CO2/N2 gas mixture (10/90 v/v) was ordered from AGA (Oslo, Norway), and deionized (DI) water was generated from a Milli-Q purification system. Membranes were prepared by solution casting from four different solvent systems increasing in Hansen solubility parameter (in MPa1/2): 50/50 v/v cyclohexane/heptane (CH, 16.1), 85/15 w/w toluene/isopropyl alcohol (TIPA, 18.3), chloroform (CF, 19.0), and tetrahydrofuran (THF, 19.5). [The polarity and hydrogen-bonding contributions to these solubility parameters are greatest for the case of THF.] In general, the TESET polymer was dissolved at 1.5 wt% in one of the selected (co)solvents under continuous agitation for at least 12 h. Each solution was poured into a Teflon dish, which was covered with a glass sheet to ensure slow drying under ambient conditions (22.5 °C and 28% RH). The resultant films were ~50 μm thick, as determined with a Digitix II thickness gauge (NSK). For membranes subjected to submersion, the films were immersed in DI water for 24 h and then dried under vacuum for another 24 h at 22.5 °C prior to analysis.

Select films before and after submersion in liquid water were stained with Pb[acetate]2 prior to embedding in epoxy and sectioning for transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Images were collected on JEOL JEM-2200FS and FEI Tecnai F20 microscopes operated at 200 kV. Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) was performed on presubmersion and postsubmersion films on beamline 12-ID-B at the Advanced Photon Source (Argonne National Laboratory). Details of the experimental setup and acquisition conditions have been previously reported28. The acquired two-dimensional scattering patterns were azimuthally integrated to yield one-dimensional intensity profiles as a function of the scattering vector q = (4π/λ)sinθ, where λ is the X-ray wavelength and θ is the scattering half-angle. Water-vapor uptake (Ω, in %) was measured by first placing each dry membrane (of mass mD) in a desiccator saturated with water vapor and then monitoring the increase in mass (Δm) as a function of exposure time so that Ω = Δm/mD × 100%. Mixed-gas permeation tests were conducted on the experimental line described elsewhere32 to interrogate the molecular transport of a CO2/N2 gas mixture at different RH levels. As a metric of gas throughput, the permeability of CO2 (\({P}_{\rm{CO}_{2}}\)) in the feed gas was determined from \({P}_{\rm{CO}_{2}} = \frac{{N}\left(1 - {y}_{\rm{H}_{2}\rm{O}} \right){y}_{\rm{CO}_{2}}{\mathrm{L}}}{{A}\left(<{p}_{\rm{CO}_{2}, \rm{feed}},{p}_{\rm{CO}_{2}, \rm{ret}}> - {p}_{\rm{CO}_{2}, \rm{perm}} \right)}\), where N is the permeate molar flow rate, A denotes the membrane permeation area, \({y}_{{\rm{H}_{2}\rm{O}}}\) and \({y}_{{\rm{CO}_{2}}}\) represent the mole fractions of water and CO2, respectively, in the permeate, and \({p}_{\rm{CO}_{2}, \rm{feed}}\), \({p}_{\rm{CO}_2, \rm{ret}}\), and \({p}_{\rm{CO}_{2}, \rm{perm}}\) identify the partial pressures of CO2 in the feed, retentate, and permeate, respectively. Gas permeability is expressed here in units of Barrer, where 1 Barrer = 10−10 cm3 (STP) cm s−1 cm−2 (cm Hg)−1, and all permeation data, collected in at least duplicate, displayed a deviation of <10% (in which case error bars are not included). An indicator of gas selectivity is the separation factor (αij), calculated from \({{\alpha }}_{ij} = ({y}_i/{x}_i)/({y}_j/{x}_j)\), where xi and xj correspond to the mole fractions of species i and j, respectively, in the feed.

Results and discussion

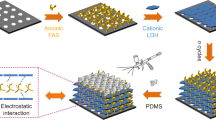

A TEM image of the nanoscale morphology formed in TIPA-cast TESET membranes prior to submersion in DI water is displayed in Fig. 1. In TEM images such as this, the dark features identify acid-rich (ionic) regions due to the selective stain employed. According to this image and 3D transmission electron microtomography results reported27 earlier, this morphology consists of discrete spherical micelles possessing a low degree of long-range order relative to, for example, a body-centered cubic lattice. Upon submersion in liquid water, a TIPA-cast TESET membrane (with a hydrophobic matrix) swells beyond 100% at ambient temperature. According to previous SAXS analysis31, it does so by first connecting the micelles along the diffusion direction as water enters the membrane and then expanding the connected and continuous hydrophilic pathways. The corresponding morphological transformation, also visible in Fig. 1, is permanent unless the membrane is redissolved and recast, and its effect on water uptake has been observed33 to become more pronounced at elevated temperatures (up to 70 °C). An interesting feature of this percolated morphology is that it serves to demonstrably improve diffusive processes, as evidenced by the photocurrent performance of photovoltaic elastomer gels containing hydrophilic photosensitive dyes compared to the parent as-cast (i.e., nonsubmerged) membrane31. The development of highly irregular, but connected, ionic channels is likewise anticipated to enhance CO2 permeation.

The SAXS profiles presented in Fig. 2a confirm that the choice of casting solvent strongly affects the morphology of TESET membranes. First, the values of the microdomain period (d), discerned from the position of the principal peak (at q*) according to Bragg’s law (d = 2π/q*), range from 37.0 (TIPA-cast) to 46.9 nm (THF-cast). Analysis of higher-order peak positions (qn, where n > 1) relative to q* (n = 1) yields the symmetry of each morphology. In the case of CF-cast films, the principal peak is relatively sharp, and values of qn/q* are calculated as 1.00, 1.97, and 2.98, indicating that the morphology is lamellar. In contrast, exposure of an ordered TESET film to CF vapor has been observed28 to promote nanostructural disordering, as evidenced by the loss and/or broadening of higher-order scattering peaks. In the case of CH, however, the principal peak is broad, and only one weak peak is visible. While the morphology of this membrane is anticipated to consist of ion-rich spherical micelles embedded in a nonpolar matrix, the lack of higher-order peaks makes such assignment inconclusive. We note, however, that the second peak ratio, estimated as 2.65 (√7), likely corresponds to spheres arranged (loosely) on a body-centered-cubic (bcc) lattice, and spherical microdomains have been identified27 in cyclohexane-cast films. As reported earlier15,28,29, SAXS profiles acquired from TIPA-cast TESET copolymers are difficult to interpret since the morphologies are not highly ordered. While the principal peak is sharp, the shoulder on the peak indicates the existence of a weak scattering peak in the vicinity of 0.250 nm−1. Including this peak, the values of qn/q* are 1.00, 1.47, and 2.22, which are all consistent with a bcc morphology, although other prominent peaks are clearly missing. Electron microscopy corroborates28,29 that TIPA-cast TESET films exhibit a spherical morphology. The asymmetry of the principal and second peaks in the case of THF-cast membranes implies that two different morphologies coexist. Prior studies have revealed27 the presence of both nonpolar cylinders and lamellae.

After submersion in water followed by drying, the morphologies of the membranes change. Mineart et al.29 have previously demonstrated that submersion of a TIPA-cast TESET film into water serves to transform the morphology from spherical to irregular and cocontinuous, wherein the ion-rich microdomains not only change size and shape but also provide fully interconnected pathways for diffusion. The corresponding SAXS profiles acquired from TESET membranes cast from different solvents and subsequently submerged in water are included in Fig. 2b. In all cases, the d-spacing is found to decrease (by ca. 6–19%) relative to that of each of the as-cast membranes shown in Fig. 2a, with the range in turn reduced: from 30.0 nm (TIPA-cast) to 44.1 nm (THF-cast). While the principal peak remains sharp, the lamellar morphology existing in the film cast from CF is almost completely disordered, with only one shallow peak remaining in the vicinity of 0.43 nm−1. The SAXS profile collected from the CH-cast membrane still displays a broad principal peak and an even weaker higher-order peak compared to its as-cast precursor, verifying that the membrane is disordered before and after submersion. Two poorly defined peaks located beyond q* are evident in the profile corresponding to the submerged TIPA-cast film, but the expected29 irregular morphology cannot be unambiguously classified. The peak positions in the profile displayed in Fig. 2b for the THF-cast membrane after submersion establishes that the morphology becomes primarily lamellar, with qn/q* values of 1.00, 2.03, and 3.07. The results presented in Fig. 2, therefore, demonstrate that the choice of casting solvent and postsubmersion in water both affect the morphology of TESET films. Below, we examine how these morphological differences translate into property changes associated with CO2 transport.

Due to their sulfonated midblock, TESET polymers swell in the presence of polar liquids, including water17, and, in the specific case of water, the extent to which they swell depends sensitively on the degree of sulfonation and the temperature33. Upon immersion in liquid water, the material (when cast from TIPA) rapidly swells (within minutes) by over 100% at ambient temperature and beyond 1000% at 70 °C. The present study, however, focuses on the permeation of CO2 through membranes maintained at different RH levels, in which case we evaluate here the sorption of water vapor in TESET membranes cast from different solvents. In Fig. 3, Ω is provided as a function of exposure time at 25 °C for membranes differing in casting solvent, and the results reveal that the choice of casting solvent has relatively little, if any, influence on uptake kinetics over the course of 300 h. At the end of this experimental time frame, all the membranes sorb approximately 50–57% water, with THF-cast membranes exhibiting slightly higher water solubility. Since these sorption curves do not appear to reach a plateau after 300 h, regression of an empirical saturation (Michaelis–Menten) function to the results included in Fig. 3 predicts that the water level at saturation does not exceed ≈65%, which is significantly less than the sorption of liquid water (other saturation models yield comparable results). The data presented in this figure confirm that, while as-cast TESET membranes sorb less water more slowly from water vapor than from liquid water, they nonetheless swell in the presence of water vapor due to the hygroscopic nature of the sulfonic acid groups residing along the styrenic midblock. Such behavior constitutes an important consideration regarding CO2 transport through dense polymer membranes.

Figure 4 displays CO2 permeabilities and CO2/N2 selectivities measured at different RH levels for presubmersion and postsubmersion TESET membranes cast from different solvents. Comparison of Fig. 4a, b establishes two important findings. The presence of water vapor generally increases CO2 permeability irrespective of membrane casting solvent and submersion history. In dry films (RH = 0%), CO2 permeability remains relatively constant, ranging from 23 to 29 Barrer for presubmersion films and from 18 to 30 Barrer for postsubmersion membranes (with postsubmersion specimens generally exhibiting slightly lower permeabilities and THF-cast materials consistently possessing the highest permeability). With the notable exception of the THF-cast sample, the CO2 permeability in presubmersion membranes increases, for the most part, with increasing RH to 53–80 Barrer. In the unique case of the THF-cast membrane, the CO2 permeability exceeds 300 Barrer at RH = 95%. According to the SAXS results described in Fig. 2a, this material possesses continuous ion-rich pathways through which both water vapor and CO2 can diffuse. After submersion, however, CO2 permeability through all the membranes becomes substantially more sensitive to RH level, increasing dramatically to 291, 436, and 482 Barrer in TIPA-, THF-, and CF-cast membranes, respectively, due presumably to the formation of irregular nanoscale channels34 that promote CO2 diffusion. In the case of the CF-cast membranes, this increase corresponds to a permeability enhancement of ≈650% and exceeds the highest CO2 permeability reported35 for a polyelectrolyte (390 Barrer in Nafion® modified with an ionic liquid at 100% RH). Even the postsubmersion membrane cast from CH exhibits a CO2 permeability of ≈100 Barrer, thereby confirming that the submersion-induced morphological transformation that disorders most of the as-cast sample morphologies (cf. Fig. 2b) is responsible for improved CO2 permeability. Although these permeabilities are promising for gas separation, the CO2/N2 selectivity must likewise be considered. Corresponding selectivity measurements are included in Fig. 4c, d, and indicate that gas humidification, as well as film submersion (especially at high RH), benefits membrane separation efficacy. Except for THF-cast specimens (which are the least selective before and after submersion), the highest selectivity values for presubmersion membranes range from 46 to 53, whereas those for postsubmersion membranes vary from 57 to 61 at ≈90% RH.

Conclusions

The need for effective and commercially viable CO2 separation membranes is becoming increasingly important for carbon capture to mitigate the threat of global climate change5. In this spirit, we have demonstrated that the morphology and, consequently, CO2 separation properties of a midblock-sulfonated multiblock polymer, which behaves as an amphiphilic thermoplastic elastomer, can be significantly altered through the use of casting solvents differing in polarity/composition and submersion in liquid water. Small-angle X-ray scattering analysis reveals the various morphological changes attributed to casting solvent and submersion in liquid water and, along with electron microscopy, indicates that submersion in water serves to connect the ionic microdomains in as-cast nanostructures. Moreover, CO2 transport properties are further enhanced through the introduction of water vapor into the feed gas. While these membranes are known17,33 to swell in the presence of liquid water, we further analyze the level to which the membranes are capable of sorbing water vapor, as well as the accompanying time frame. According to mixed-gas permeation tests, both CO2 permeability and CO2/N2 selectivity are generally improved through the use of gas feed humidification. Moreover, at comparable RH levels, membrane submersion in liquid water further benefits CO2 permeability (by an increase of 650% to 482 Barrer) and concurrently improves CO2/N2 selectivity (by 34% to 61). To put these results in perspective, we have assembled all the data collected here in a so-called Robeson plot7,36, displayed in Fig. 5. Of particular importance here is the upper bound, which provides an empirical limit on the permeability-selectivity trade-off based on numerous experimental observations. It is evident from our data that increased RH consistently benefits the overall performance of our membranes. We hasten to note that two postsubmersion membranes surpass the upper bound. The encouraging results reported herein provide complementary materials design and operation paradigms by which midblock-charged multiblock polymers can be employed for the selective removal of CO2 from atmospheric emissions.

References

Bernardo, P., Drioli, E. & Golemme, G. Membrane gas separation: a review/state of the art. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 48, 4638–4663 (2009).

Himma, N. F., Wardani, A. K., Prasetya, N., Aryanti, P. T., Wenten, I. G. Recent progress and challenges in membrane-based O2/N2 separation. Rev. Chem. Eng. 35, 591–625 (2018).

Xing, R. & Ho, W. W. Crosslinked polyvinylalcohol–polysiloxane/fumed silica mixed matrix membranes containing amines for CO2/H2 separation. J. Membr. Sci. 367, 91–102 (2011).

Liu, J., Zhang, G., Clark, K. & Lin, H. Maximizing ether oxygen content in polymers for membrane CO2 removal from natural gas. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 10933–10940 (2019).

Davis, S. J., Caldeira, K. & Matthews, H. D. Future CO2 emissions and climate change from existing energy infrastructure. Science 329, 1330–1333 (2010).

Merkel, T. C. et al. Ultrapermeable, reverse-selective nanocomposite membranes. Science 296, 519–522 (2002).

Park, H. B., Kamcev, J., Robeson, L. M., Elimelech, M. & Freeman, B. D. Maximizing the right stuff: the trade-off between membrane permeability and selectivity. Science 356, eaab0530 (2017).

Baker, R. W. & Low, B. T. Gas separation membrane materials: a perspective. Macromolecules 47, 6999–7013 (2014).

Lalia, B. S., Kochkodan, V., Hashaikeh, R. & Hilal, N. A review on membrane fabrication: structure, properties and performance relationship. Desalination 326, 77–95 (2013).

Khulbe, K. C., Matsuura, T., Lamarche, G. & Kim, H. J. The morphology characterisation and performance of dense PPO membranes for gas separation. J. Membr. Sci. 135, 211–223 (1997).

Kesting, R. E. The solvent size effect: solvents and solvent complexes viewed as transient templates which control free volume in the skins of integrally-skinned phase inversion. Membr. J. Polym. Sci. C 27, 187–190 (1989).

Huertas, R. M., Maya, E. M., De Abajo, J. & De La Campa, J. G. Effect of 3, 5-diaminobenzoic acid content, casting solvent, and physical aging on gas permeation properties of copolyimides containing pendant acid groups. Macromol. Res. 19, 797–808 (2011).

Dai, Z., Løining, V., Deng, J., Ansaloni, L. & Deng, L. Poly(1-trimethylsilyl-1-propyne)-based hybrid membranes: effects of various nanofillers and feed gas humidity on CO2 permeation. Membranes 8, 76 (2018).

Isanejad, M., Azizi, N. & Mohammadi, T. Pebax membrane for CO2/CH4 separation: effects of various solvents on morphology and performance. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 134, 44531 (2017).

Ansaloni, L. et al. Solvent-templated block ionomers for base- and acid-gas separations: effect of humidity on ammonia and carbon dioxide permeation. Adv. Mater. Interf. 4, 1700854 (2017).

Willis, C. L., Handlin, D. L., Trenor, S. R., Mather, B. D. Sulfonated Block Copolymers, Method for Making Same, and Various Uses for Such Block Copolymers, U.S. Patent US7737224 B2 (2010).

Geise, G. M., Freeman, B. D. & Paul, D. R. characterization of a sulfonated pentablock copolymer for desalination applications. Polymer 51, 5815–5822 (2010).

Chen, S. H., Willis, C. & Shull, K. R. Water transport and mechanical response of block copolymer ion-exchange membranes for water purification. J. Membr. Sci. 544, 388–396 (2017).

Shi, G. M., Zuo, J., Tang, S. H., Wei, S. & Chung, T. S. Layer-by-layer (LbL) polyelectrolyte membrane with Nexar™ polymer as a polyanion for pervaporation dehydration of ethanol. Sep. Purif. Technol. 140, 13–22 (2015).

Vargantwar, P. H., Roskov, K. E., Ghosh, T. K. & Spontak, R. J. Enhanced biomimetic performance of ionic polymer–metal composite actuators prepared with nanostructured block ionomers. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 33, 61–68 (2012).

Peddinti, B. S. T., Scholle, F., Vargas, M. G., Smith, S. D., Ghiladi, R. A. & Spontak, R. J. Inherently self-sterilizing charged multiblock polymers that kill drug-resistant microbes in minutes. Mater. Horiz. (2019, Advance Article) https://doi.org/10.1039/C9MH00726A.

Al-Mohsin, H. A., Mineart, K. P. & Spontak, R. J. Highly flexible aqueous photovoltaic elastomer gels derived from sulfonated block ionomers. Adv. Energy Mater. 5, 1401941 (2015).

Hamley, I. W. (ed.). Developments in Block Copolymer Science and Technology. (Wiley, New York, 2004).

Bates, C. M. & Bates, F. S. 50th Anniversary perspective: block polymers—pure potential. Macromolecules 50, 3–22 (2016).

Park, M. J. & Balsara, N. P. Phase behavior of symmetric sulfonated block copolymers. Macromolecules 41, 3678–3687 (2008).

Griffin, P. J., Salmon, G. B., Ford, J. & Winey, K. I. Predicting the solution morphology of a sulfonated pentablock copolymer in binary solvent mixtures. J. Polym. Sci. B 54, 254–262 (2016).

Mineart, K. P., Jiang, X., Jinnai, H., Takahara, A. & Spontak, R. J. Morphological investigation of midblock-sulfonated block ionomers prepared from solvents differing in polarity. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 36, 432–438 (2015).

Mineart, K. P., Lee, B. & Spontak, R. J. A solvent-vapor approach toward the control of block ionomer morphologies. Macromolecules 49, 3126–3137 (2016).

Fan, Y., Zhang, M., Moore, R. B. & Cornelius, C. J. Structure, physical properties, and molecule transport of gas, liquid, and ions within a pentablock copolymer. J. Membr. Sci. 464, 179–187 (2014).

Fan, Y. & Cornelius, C. J. Raman spectroscopic and gas transport study of a pentablock ionomer complexed with metal ions and its relationship to physical properties. J. Mater. Sci. 48, 1153–1161 (2013).

Mineart, K. P., Al-Mohsin, H. A., Lee, B. & Spontak, R. J. Water-induced nanochannel networks in self-assembled block ionomers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 108, 101907 (2016).

Dai, Z. et al. Fabrication and evaluation of bio-based nanocomposite TFC hollow fiber membranes for enhanced CO2 capture. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 10874–10882 (2019).

Mineart, K. P. et al. Hydrothermal conditioning of physical hydrogels prepared from a midblock-sulfonated multiblock copolymer. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 38, 1600666 (2017).

Zavala-Rivera, P. et al. Collective osmotic shock in ordered materials. Nat. Mater. 11, 53–57 (2012).

Dai, Z., Ansaloni, L., Ryan, J. J., Spontak, R. J. & Deng, L. Nafion/IL hybrid membranes with tuned nanostructure for enhanced CO2 separation: effects of ionic liquid and water vapor. Green Chem. 20, 1391–1404 (2018).

Robeson, L. M. The upper bound revisited. J. Membr. Sci. 320, 390–400 (2008).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the European Commission within the NanoMEMC2 project in the Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under Grant Agreement no. 727734. We also thank the NC State Nonwovens Institute for financial support and Dr. B. Lee at Argonne National Laboratory for technical assistance. This research used resources at the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract no. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dai, Z., Deng, J., Aboukeila, H. et al. Highly CO2-permeable membranes derived from a midblock-sulfonated multiblock polymer after submersion in water. NPG Asia Mater 11, 53 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41427-019-0155-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41427-019-0155-5